Abstract

Most organisms form Cys-tRNACys, an essential component for protein synthesis, through the action of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CysRS). However, the genomes of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, and Methanopyrus kandleri do not contain a recognizable cysS gene encoding CysRS. It was reported that M. jannaschii prolyl-tRNA synthetase (C. Stathopoulos, T. Li, R. Longman, U. C. Vothknecht, H. D. Becker, M. Ibba, and D. Söll, Science 287:479-482, 2000; R. S. Lipman, K. R. Sowers, and Y. M. Hou, Biochemistry 39:7792-7798, 2000) or the M. jannaschii MJ1477 protein (C. Fabrega, M. A. Farrow, B. Mukhopadhyay, V. de Crécy-Lagard, A. R. Ortiz, and P. Schimmel, Nature 411:110-114, 2001) provides the “missing” CysRS activity for in vivo Cys-tRNACys formation. These conclusions were supported by complementation of temperature-sensitive Escherichia coli cysS(Ts) strain UQ818 with archaeal proS genes (encoding prolyl-tRNA synthetase) or with the Deinococcus radiodurans DR0705 gene, the ortholog of the MJ1477 gene. Here we show that E. coli UQ818 harbors a mutation (V27E) in CysRS; the largest differences compared to the wild-type enzyme are a fourfold increase in the Km for cysteine and a ninefold reduction in the kcat for ATP. While transformants of E. coli UQ818 with archaeal and bacterial cysS genes grew at a nonpermissive temperature, growth was also supported by elevated intracellular cysteine levels, e.g., by transformation with an E. coli cysE allele (encoding serine acetyltransferase) or by the addition of cysteine to the culture medium. An E. coli cysS deletion strain permitted a stringent complementation test; growth could be supported only by archaeal or bacterial cysS genes and not by archaeal proS genes or the D. radiodurans DR0705 gene. Construction of a D. radiodurans DR0705 deletion strain showed this gene to be dispensable. However, attempts to delete D. radiodurans cysS failed, suggesting that this is an essential Deinococcus gene. These results imply that it is not established that proS or MJ1477 gene products catalyze Cys-tRNACys synthesis in M. jannaschii. Thus, the mechanism of Cys-tRNACys formation in M. jannaschii still remains to be discovered.

Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CysRS), a highly conserved essential enzyme, is a key component in protein biosynthesis. It is the smallest monomeric class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (14, 20). A recent determination of the crystal structure of Escherichia coli CysRS (30) revealed that a zinc ion positioned at the active site is responsible for the precise binding of the substrate cysteine. This metal ion coordinates with the side chains of Cys28, Cys209, His234, and Glu238 (30). CysRS is well conserved in all three domains of life; phylogenetic studies suggest a transfer of cysS from bacteria to some archaea (24). Based on the knowledge of a large number of complete organism genomes, it is clear that only three methanogenic archaea, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (8), Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (33), and Methanopyrus kandleri (32), do not contain an open reading frame (ORF) resembling that for CysRS.

How is Cys-tRNACys formed in these methanogenic archaea? One apparent answer came from reports that archaeal prolyl-tRNA synthetases (ProRSs) could form Cys-tRNACys in addition to Pro-tRNAPro (26, 35). Apart from biochemical data, the conclusion was based on the persuasive in vivo result (35) that the M. jannaschii, M. thermautotrophicus, and Methanococcus maripaludis proS genes could restore the growth, albeit weakly, of temperature-sensitive E. coli cysS(Ts) strain UQ818 (5) at a nonpermissive temperature. Poor growth of the transformed strains was attributed to slow translation in E. coli of the large number of AGA codons present in the archaeal proS genes (35). A different route to archaeal Cys-tRNACys formation was proposed on the basis of the existence of an unusual aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase that lacks the typical features of class I and class II synthetases and is encoded by the M. jannaschii MJ1477 ORF (15). The heterologously expressed MJ1477 protein was shown to cysteinylate in vitro both M. jannaschii total tRNA and purified E. coli tRNACys, but the MJ1477 gene could not rescue the growth of E. coli cysS(Ts) strain UQ818 (15). Instead, DR0705, the Deinococcus radiodurans ortholog of MJ1477, was shown to complement strain UQ818. While these data suggested that MJ1477 provides Cys-tRNACys in M. jannaschii, MJ1477 orthologs are not present in the genomes of M. thermautotrophicus (33) or the viable cysS deletion strain (36) of M. maripaludis (J. Leigh, unpublished data).

In both of the above-mentioned studies (15, 35), the conclusions were based on the weak complementation of E. coli strain UQ818 by the archaeal proS genes or the D. radiodurans DR0705 gene. E. coli UQ818 has a thermolabile CysRS; cell extracts display little CysRS activity at 33°C (5). Strain UQ818 does not grow at the nonpermissive temperature of 41°C but does grow after complementation with cysS genes from E. coli (14, 20) or from M. maripaludis or Methanosarcina barkeri (24). A characterization of the cysS mutation in strain UQ818 has not been reported.

Although the finding that archaeal ProRSs form Cys-tRNACys has been reported repeatedly (9, 26, 27, 34, 35), a biochemical reexamination of the amino acid recognition of ProRS enzymes showed that cysteine charging in vitro is a property of ProRS enzymes from all domains (1); however, the reaction product is the misacylated Cys-tRNAPro species (2). Therefore, we wanted to further examine the in vivo complementation of E. coli cysS(Ts) strain UQ818 and to analyze the complementation of an E. coli cysS deletion strain (ΔcysS). In addition, we attempted to evaluate the physiological significance of DR0705 by using a gene deletion in D. radiodurans (3).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General.

[35S]Cysteine (1,075 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences (Boston, Mass.). [14C]Serine (155 mCi/mmol) was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). E. coli total tRNA was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), and the TOPO-TA cloning kit was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, Calif.). Oligonucleotide synthesis and DNA sequencing were performed at the Keck Foundation Research Biotechnology Resource Laboratory at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.). Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (6) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Plasmids, strains, and culture medium.

Table 1 lists the plasmids and strains used in this study. Primers were designed to PCR amplify each ORF and introduce the desired restriction sites. The forward primers contained a restriction site and 20 nucleotides identical to the start sequence of the 5′ end; the reverse primers contained a restriction site and 20 nucleotides complementary to the sequence of the 3′ end. Standard PCR procedures were used to generate the coding sequences of the M. jannaschii proS, M. maripaludis proS and cysS, D. radiodurans DR0705 and cysS, and E. coli cysE and cysS genes from their corresponding genomic DNAs. The amplified coding sequences were cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector. After verification of the DNA sequences, the genes were subcloned into the desired vector. For in vivo complementation, the genes were subcloned into the pCYB1 vector between the NdeI and BamHI sites under the control of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible tac promoter. An E. coli cysE mutant allele, cysEM256I (10), was generated by PCR mutagenesis of the cysE gene (created above) with primers that contained the corresponding mutation.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant information | Reference or sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| W3110 | Wild type | |

| UQ818 | lacZ4 gyrA222 (nalR) aroE24 metB rpoB (rifR) cysS818 | 5 |

| BL21(DE3) | 37 | |

| DY330 | lacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) | 39 |

| EC723 | lacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) nad+ araCBAD::tolC | J. A. DeVito, unpublished data |

| EC400 | lacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) araCBAD::lox2-kan | J. A. Mills, unpublished data |

| ΔcysS | EC723 cysS::lox2-kan | This work |

| D. radiodurans R1 | ATCC 13939 | ATCC; 17 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET15b | Vector | Novagen |

| pET15b-cysS | E. coli cysS | This work |

| pET15b-cysSV27E | E. coli cysS (Ts) | This work |

| pET28a | Vector | Novagen |

| pBAD18-Cm | Vector | ATCC |

| pBADbr | Replace replication origin of pBAD18-Cm with that of pET28a | This work |

| pBADbrcysS | E. coli cysS | This work |

| pACYC184 | Vector | NEB |

| pACYC-Tc-Mj-tRNACys | M. jannaschii tRNACys | This work |

| pCYB1 | Vector | NEB |

| pCYB-MJproS | M. jannaschii proS | This work |

| pCYB-MMproS | M. maripaludis proS | This work |

| pCYB-MMcysS | M. maripaludis cysS | This work |

| pCYB-DR0705 | D. radiodurans DR0705 | This work |

| pCYB-DRcysS | D. radiodurans cysS | This work |

| pCYB-DRproS | D. radiodurans proS | This work |

| pCYB-cysE | E. coli cysE | This work |

| pCYB-ECcysS | E. coli cysS | This work |

| pCYB-cysEM256I | E. coli cysEM256I | This work |

| pGEM-T | Vector | Promega |

| pTNK102 | pGEM-T containing PkatA-npt | This work |

| pTNK301 | DR0705 deletion cassette containing PkatA-npt | This work |

| pTNK302 | DR1670 deletion cassette containing PkatA-cat | This work |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; NEB, New England BioLabs.

A medium-copy-number vector, pBADbr, was constructed with the arabinose promoter from pBAD18-Cm and the replication origin from pET28a by using BglII and ClaI restriction sites. The E. coli cysS gene was cloned into its NheI and SacI sites to generate pBADbrcysS.

The M. jannaschii tRNACys gene behind the lpp promoter was subcloned from pTech-Mj-tRNACys (35) into pACYC184 by using restriction enzymes AvaI and BstZ171. This procedure removed the cat gene from pACYC184. The resulting plasmid, pACYC-Tc-Mj-tRNACys, confers tetracycline resistance.

The following antibiotics at the concentrations indicated were used in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (31): ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml), kanamycin (20 μg/ml), and tetracycline (20 μg/ml). The final concentrations of arabinose and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) in the culture medium were 0.02% and 1 mM, respectively.

Cloning of E. coli cysS genes and purification of CysRS enzymes.

Genomic DNA of E. coli strain W3110 or UQ818 was used. PCR primers were designed to amplify the cysS ORF, and the resulting DNA fragment was cloned into the pET15b vector at the NdeI and BamHI sites for expression of proteins as N-terminal His6-tagged proteins. These pET15b-cysS clones were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, and the transformants were grown in 500 ml of LB-ampicillin medium to a cell density (A600) of 0.4. At this point, cysS expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG treatment for 2 h. Cells were harvested and lysed, and wild-type and mutant His6-CysRS proteins were purified from cell extracts by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose chromatography as described in the Qiagen (Valencia, Calif.) protein purification manual. Both proteins were judged to be >95% pure by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis after Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Active-site titration showed that the CysRS and CysRSV27E (CysRS with a V27E mutation) preparations contained 100 and 52% active enzymes, respectively. These values were used to determine enzyme concentrations for the calculation of kcat. The enzymes were stored in 10% glycerol in 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.0)-50 mM KCl-15 mM MgCl2-5 mM dithiothreitol at −20°C.

Assay for CysRS activity.

Cys-tRNA formation was measured as acid-precipitable radioactivity as described previously (1). The standard reaction mixture contained 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM ATP, 0.2 mM [35S]cysteine, and 10 mg of unfractionated E. coli tRNA/ml (unless specified otherwise) in a final volume of 0.1 ml. The final enzyme concentrations were 0.37 nM for CysRS and 1.6 nM for CysRSV27E. Initial velocities were measured at 30°C. The substrate concentrations ranged from 0.01 to 20 times the Km values, and the experiments were done in triplicate.

Active-site titration of CysRS enzymes.

CysRS preparations were incubated at 30°C in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-10 mM KCl-10 mM MgCl2-4 mM ATP (pH 7)-200 μM [35S]cysteine (650 cpm/pmol)-5 mM dithiothreitol-1 U of inorganic pyrophosphatase in a total volume of 0.1 ml. Aliquots (25 μl) were used at various times for active-site titration as described previously (1).

Growth of E. coli UQ818 at nonpermissive temperatures under various conditions.

A cysteine gradient plate (12) was used to show the growth of UQ818 at nonpermissive temperatures in the presence of cysteine. UQ818 cells were grown overnight in LB medium. A 10−4 dilution of the overnight culture (0.1 ml) was spread on a λ plate (1% Bacto Tryptone, 0.5% sodium chloride, 1.5% agar). After the plate was dried, an aliquot (0.15 ml) of cysteine (0.4 M) was placed in a central well, and the plate was incubated for 2 days at 41°C.

In order to evaluate the growth restored by cysEM256I, UQ818 was transformed with pCYB1, pCYB-ECcysS, pCYB-cysEM256I, or pCYB-MMcysS. The transformants were cultured overnight in LB-ampicillin medium, and the liquid cultures (one loop) were streaked on LB-ampicillin agar plates containing 1 mM IPTG. The plates were grown at 30 or 41°C for 2 days.

In order to compare the growth restored by various genes, we measured at 42°C the growth curves for W3110 cells and UQ818 cells transformed with pCYB-ECcysS, pCYB-MMcysS, pCYB-DR0705, pCYB-MMproS, pCYB-MJproS, pCYB-ECcysEM256I, or pCYB1. UQ818 transformants with archaeal proS genes also contained an M. jannaschii tRNACys gene (35). Each strain from an overnight culture was inoculated into LB medium with antibiotics and IPTG in triplicate and grown at 42°C for 8 h. Aliquots (1 ml) were taken every 0.5 h to measure the A600.

Construction of an E. coli cysS chromosomal deletion strain.

An E. coli chromosomal deletion strain was constructed by using the generalized recombination system of bacteriophage λ (39). The cysS gene was expressed from an arabinose regulon on pBADbrcysS, while the chromosomal cysS copy in E. coli strain EC723 was replaced with a lox‡-kan cassette (18). The details of strain construction were adapted from the method of Yu et al. (39). The genomic DNA of E. coli strain EC400 served as the template for PCR amplification of the lox2-kan cassette (11), and the resulting cassette was flanked with 50-bp sequences identical to those found in the upstream and downstream regions of the cysS gene. The deletion cassette was transformed into heat-shocked (15 min) E. coli strain EC723 containing a rescue plasmid, pBADbrcysS. Transformants were selected on kanamycin plates, and strains containing a cysS chromosomal deletion were screened by PCR and nucleotide sequencing.

Plasmid exchange experiments with the E. coli cysS chromosomal deletion strain.

The cysS chromosomal deletion strain was further transformed with pACYC-Tc-Mj-tRNACys, which provides M. jannaschii tRNACys for M. jannaschii cysS to function in E. coli (35). The resulting strain was transformed by electroporation (31) with pCYB derivative plasmids (50 ng) containing cysS or other genes at 30°C to prevent lysis of the host (39). Transformants were cultured in LB medium containing kanamycin and tetracycline for 60 min, and then a series of dilutions of the transformants were spread on LB agar plates containing kanamycin, tetracycline, ampicillin, l-arabinose, and IPTG. Cells were grown at 30°C for 1 day, and the numbers of ampicillin-resistant colonies were counted. Colonies then were replicated to LB agar plates containing either chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml) or ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and also containing kanamycin, tetracycline, l-arabinose, and IPTG. After 24 h of incubation, the growth of the replicants was checked.

Construction of plasmids for use in deleting DR0705 and cysS (DR1670) from the D. radiodurans R1 genome.

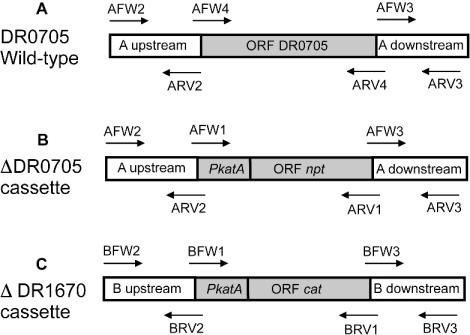

The plasmid used for DR0705 deletion, pTNK301 (carrying the DR0705 deletion cassette) (Fig. 1B), was generated in a three-step process by splicing by overlap extension (13, 19). The Tn903 neomycin phosphotransferase gene (npt) was fused to a 120-bp sequence upstream of the initiation codon of the D. radiodurans R1 katA gene (PkatA in Fig. 1) (16). The primers shown in Fig. 1B were used for PCR to amplify the 806-bp sequence immediately downstream of the DR0705 termination codon and the 971-bp sequence upstream of the DR0705 initiation codon and for PCR to splice both fragments to the PkatA-npt cassette. The resulting cassette was cloned into pGEM-T to give pTNK301 for DR0705 deletion.

FIG. 1.

Scheme of cassette constructs for Deinococcus gene deletions. (A) DR0705 in the D. radiodurans R1 chromosome. (B) DR0705 deletion cassette. (C) DR1670 deletion cassette. Primers indicated above or below the cassette were used for PCR. Sections of the diagrams are labeled as follows: A upstream, 971 bp immediately upstream of the initiation codon of DR0705; A downstream, 806 bp immediately downstream of the termination codon of DR0705; B upstream, 886 bp immediately upstream of the initiation codon of DR1670; B downstream, 957 bp immediately downstream of the termination codon of DR1670.

The plasmid used for cysS (DR1670) deletion, pTNK302 (carrying the DR1670 deletion cassette) (Fig. 1C), was generated in a manner similar to that used for constructing pTNK301. The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene from pBC (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was spliced to the D. radiodurans katA promoter. The resulting PkatA-cat fragment was fused to a 957-bp sequence downstream of DR1670 and to an 886-bp sequence immediately upstream of DR1670 by overlap extension, and the resulting product was cloned into pGEM-T to give pTNK302.

Deletion of DR0705 from D. radiodurans R1.

DR0705 was disrupted by targeted mutagenesis as described previously (13). The DR0705 deletion cassette (Fig. 1B) was transformed into an exponential-phase D. radiodurans R1 culture, and the recombinants were selected on tryptone-glucose-yeast extract (TGY) plates containing kanamycin (10 μg/ml). Since D. radiodurans is multigenomic, individual colonies had to be screened to determine whether they were homozygous for the disruption. Genomic DNAs of the individual recombinants were extracted and subjected to PCR analysis for the existence of wild-type DR0705 or the deletion cassette. Briefly, putative deletion mutants were subjected to PCR amplification for wild-type DR0705 with primers AFW4 and ARV4 (Fig. 1A). No PCR product should be obtained if DR0705 has been deleted. To verify the disruption, genomic DNAs from D. radiodurans R1 and the DR0705 deletion strain were PCR amplified to obtain DNA fragments of the deletion region with primers AFW2 and ARV3 (Fig. 1A and B), and the amplified DNA fragments (∼2.7 kb) were further subjected to HindIII and XhoI digestions. The npt gene-containing fragments should be cut in half, because the npt gene, but not DR0705, contains single restriction sites for HindIII and XhoI.

Deletion of cysS from D. radiodurans R1.

The cysS (DR1670) deletion cassette (Fig. 1C) was transformed into exponential-phase D. radiodurans R1 cells by the CaCl2 method (13). The culture was spread on TGY plates containing chloramphenicol (3 μg/ml) and incubated at 30°C. Recombinants were observed on these plates within 6 days. Candidates were purified in three rounds of single-colony isolation. Then, chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were PCR screened for the loss of cysS by using genomic DNA isolated from each candidate.

RESULTS

The mutant CysRS in strain UQ818 is defective in cysteine binding.

E. coli strain UQ818 was isolated as a spontaneous temperature-sensitive mutant and lacks CysRS activity in vitro at 42°C (5). In order to characterize the CysRS in this strain, we cloned and sequenced the cysS(Ts) gene. We found a single nucleotide change (T→A at position 80) leading to a V→E change at position 27 of the CysRS protein. Sequence alignment of 76 canonical CysRS proteins showed that valine is the most abundant amino acid at position 27 (in 51 out of 76 proteins), the other amino acids being leucine, threonine, cysteine, alanine, tyrosine, asparagine, and glycine.

To understand the effect of the V27E mutation on cysteinylation, the N-terminal His6-tagged CysRS and CysRSV27E enzymes were overexpressed and purified on an Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid matrix. Aminoacylation kinetics were determined at 30°C, a temperature at which the CysRSV27E enzyme retains activity. The results (Table 2) indicated a significant difference in the Km values for cysteine (7.2 and 28.2 μM, respectively). The Km values for the other substrates, tRNA and ATP, did not differ significantly for the mutant and wild-type enzymes. However, the kcat values for both substrates were about four- to ninefold lower in the mutant, with a ninefold decrease in the value for ATP. Kinetic constants for other CysRS enzymes were determined earlier by ATP-PPi exchange (23, 29); thus, they are not strictly comparable to our aminoacylation data. However, our values are in the range of values reported for CysRS enzymes from E. coli (0.4 μM for tRNACys), mammals (0.8 μM for tRNACys, 800 μM for ATP, and 11 μM for cysteine), and yeasts (0.54 μM for tRNACys, 80 μM for ATP, and 8 μM for cysteine). The V27E mutation does not affect the discrimination of the enzyme for serine, which was not charged by either wild-type or mutant CysRS (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of wild-type and mutant E. coli CysRS enzymes

| Substrate | Enzyme | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tRNACysa | CysRS | 0.64 ± 0.09 | 2.9 ± 0.17 | 4.5 |

| CysRSV27E | 0.92 ± 0.08 | 0.68 ± 0.027 | 0.74 | |

| ATP | CysRS | 338 ± 60 | 4.4 ± 0.34 | 0.013 |

| CysRSV27E | 412 ± 54 | 0.48 ± 0.018 | 0.0012 | |

| Cysteine | CysRS | 7.2 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 0.41 | 0.67 |

| CysRSV27E | 28.2 ± 1.7 | 0.86 ± 0.015 | 0.030 |

The Km for tRNA was measured with unfractionated E. coli tRNA containing 1% tRNACys (determined by plateau charging with E. coli CysRS).

Complementation of the temperature-sensitive phenotype of E. coli cysS(Ts) strain UQ818.

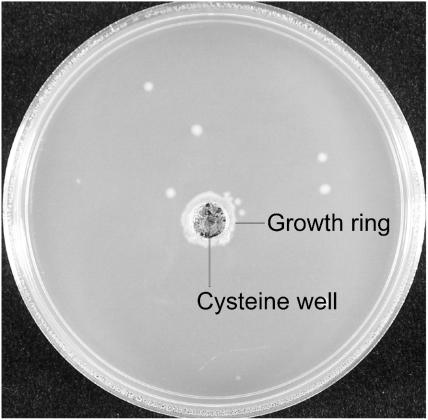

Since the mutant CysRSV27E enzyme is impaired in cysteine binding, we tested whether elevated cysteine levels in E. coli UQ818 cells would restore their ability to grow at a nonpermissive temperature on a cysteine gradient plate (12). Only cells located close to the cysteine-containing well grew after 2 days of incubation at 41°C, apart from some revertant colonies (Fig. 2). Thus, elevated cysteine levels can restore the growth of the cysS(Ts) strain at a nonpermissive temperature.

FIG. 2.

Growth of E. coli cysS(Ts) strain UQ818 at 41°C on a cysteine gradient λ plate. The highest cysteine concentration is in the well (see Materials and Methods).

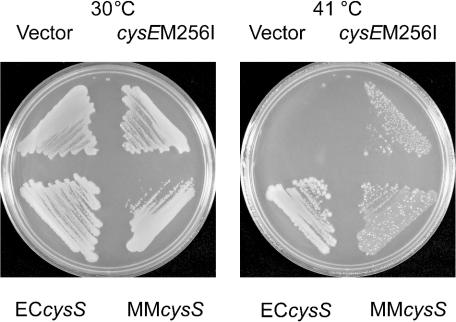

To investigate the possibility that an elevation in cysteine biosynthetic capacity would also rescue growth, we transformed the E. coli cysS(Ts) strain with a cysE allele encoding serine acetyltransferase. This enzyme converts serine to O-acetylserine, the direct precursor of cysteine (10). Since serine acetyltransferase is feedback inhibited by cysteine, a feedback-resistant mutant enzyme, CysEM256I (10), was selected; an E. coli cysEM256I strain excretes up to 2.5 mM cysteine into the medium (10). Therefore, we transformed UQ818 cells with cysEM256I (cloned into pCYB) and used the E. coli and M. maripaludis cysS genes as controls. As expected, cysEM256I rescued the growth of strain UQ818 at 41°C, albeit not as well as did the E. coli and M. maripaludis cysS genes (Fig. 3). Taken together, these results suggest that increased cellular cysteine levels enable E. coli UQ818 to grow at a nonpermissive temperature.

FIG. 3.

Complementation of E. coli cysS(Ts) strain UQ818 with pCYB1, pCYB-ECcysS, pCYB-cysEM256I, or pCYB-MMcysS. LB agar containing ampicillin and IPTG was used for growth at 41°C (see Materials and Methods).

Since it was previously reported that the M. maripaludis proS gene (35) or the D. radiodurans DR0705 gene (15) also rescues the high-temperature growth of E. coli strain UQ818, we wanted to compare the rates of growth of these transformants with those of transformants complemented with the cysS genes. E. coli strain UQ818 (carrying an M. jannaschii tRNACys gene) does not grow at 42°C; however, strains complemented with the cysS genes grew at 42°C. The observed doubling times for W3110, UQ818 with E. coli cysS, and UQ818 with M. maripaludis cysS were 0.5, 1, and 2 h, respectively. However, no growth (defined as no appreciable change in the A600 during the experiment; after 8 h, the absorbance was <4% that of wild-type strain W3110) was observed in LB medium for strain UQ818 containing D. radiodurans DR0705, M. jannaschii proS, M. maripaludis proS, or E. coli cysEM256I (data not shown).

Only canonical cysS genes restore CysRS function to an E. coli cysS deletion strain.

Because complementation of the cysS(Ts) gene in strain UQ818 is fraught with pitfalls, we constructed an E. coli cysS chromosomal deletion strain in order to perform an unambiguous test. Survival of a cysS deletion strain can be maintained with a rescue plasmid carrying E. coli cysS. This chloramphenicol-resistant plasmid, pBADbrcysS, can be replaced by transformation and selection for an incompatible plasmid carrying a functional cysS gene. We have constructed such incompatible plasmids (pCYB derivatives) that are ampicillin resistant. The pCYB plasmids contain various ORFs in order to test their ability to complement the E. coli cysS deletion strain. Upon transformation of the deletion strain, cells carrying only a pCYB plasmid (pBADbrcysS being lost due to plasmid incompatibility) would be chloramphenicol sensitive. Cells still containing both plasmids would be ampicillin and chloramphenicol resistant. Therefore, the CysRS activity encoded by genes cloned into pCYB can be assessed by their ability to replace the pBADbrcysS rescue plasmid in the E. coli cysS deletion strain.

pCYB transformants of the ΔcysS strain were selected on ampicillin and then screened for chloramphenicol sensitivity to assess the efficiency of plasmid exchange. When pCYB plasmids containing cysS genes from E. coli or M. maripaludis were tested, transformation efficiencies were increased and the efficiency of plasmid exchange was high (Table 3). Even though the same amount of plasmid DNA (50 ng) was used for transformation of the same batch of competent E. coli ΔcysS cells, the number of transformants was greatly reduced in the ΔcysS strain when pCYB plasmids without functional cysS genes were introduced (Table 3). Presumably, selection against the pBADbrcysS rescue plasmid did not allow enough cysS to be expressed for functional complementation of the cysS chromosomal deletion. When the transformants were tested for chloramphenicol resistance, >90% of the proS or DR0705 transformants retained the pBADbrcysS rescue plasmid (Table 3); this result indicates that proS or DR0705 does not provide cysS function. Thus, proS and DR0705 do not encode a CysRS that is functional in E. coli.

TABLE 3.

Plasmid exchange in the E. coli ΔcysS straina

| Plasmid | No. of:

|

% Plasmid exchangec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampr colonies | Ampr Cms coloniesb | ||

| pCYB-ECcysS | 240,000 | 47 | 94 |

| pCYB-MMcysS | 58,000 | 38 | 18 |

| pCYB-MMproS | 74 | 2 | 0.001 |

| pCYB-DR0705 | 52 | 1 | 0.0004 |

| pCYB empty vector | 58 | 3 | 0.001 |

Because the rescue plasmid, pBADbrcysS (Cmr), could be replaced by pCYB (Ampr)-derived plasmids containing a functional cysS gene, the resulting transformants should be ampicillin resistant and chloramphenicol sensitive.

Fifty colonies from each strain were tested for ampicillin resistance and chloramphenicol sensitivity, a direct measure of the CysRS activity encoded by the test genes.

The percentage of cells containing the exchanged plasmids was calculated as follows: [(Ampr Cms colonies/50) × (Ampr colonies/240,000)] × 100. It was assumed that the same number of transformants (240,000/50 ng of plasmid) would be obtained with each plasmid tested and that the 50 tested colonies were representative of the entire pool of ampicillin-resistant colonies.

Deletion of DR0705 from D. radiodurans R1 generates a viable strain.

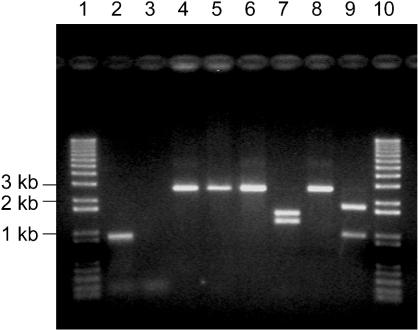

DR0705 was deleted from the D. radiodurans R1 chromosome and replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette under the control of a constitutively expressed D. radiodurans promoter. The results of experiments with the DR0705 deletion strain, designated TNK201, are shown in Fig. 4. Amplification of the 924-bp DR0705 ORF was not observed when genomic DNA of TNK201 was used as a template, although an ∼900-bp fragment was obtained when D. radiodurans R1 genomic DNA was used as a template (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 3). These results suggest that DR0705 had been replaced with the PkatA-npt cassette in TNK201. To verify the disruption, genomic DNAs from R1 and TNK201 were amplified with primers AFW2 and ARV3 (Fig. 1A and B), and DNA fragments of 2.7 kb were obtained (Fig. 4, lanes 4 and 5). Both purified DNA fragments were digested with HindIII and XhoI; HindIII cut the TNK201-derived PCR product into fragments of 1.2 and 1.5 kb, while R1-derived DNA remained intact (Fig. 4, lanes 6 and 7). Similarly, XhoI cut the TNK201-derived PCR product into 1- and 1.7-kb fragments but not the product amplified from R1 (Fig. 4, lanes 8 and 9). These results confirm that DR0705 had been deleted from strain TNK201 and replaced with the PkatA-npt cassette. The deletion strain (TNK201) grew with the same kinetics as its R1 parent (with a doubling time of ∼1 h in TGY broth at 30°C). Thus, DR0705 is not essential for the growth of this Deinococcus strain.

FIG. 4.

Replacement of the D. radiodurans DR0705 gene with the PkatA-npt cassette. Lanes 1 and 10, DNA size markers; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, DNA from D. radiodurans R1; lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9, DNA from DR0705 deletion strain TNK201. Lanes: 2 and 3, PCR products of primers AFW4 and ARV4; 4 and 5, PCR products of primers AFW2 and ARV3; 6 and 7, HindIII digestion of DNA in lanes 4 and 5, respectively; 8 and 9, XhoI digestion of DNA in lanes 4 and 5, respectively. DR0705 has no restriction sites for HindIII and XhoI, while the npt gene is cut once by both enzymes.

Attempts to delete cysS from D. radiodurans R1 were unsuccessful.

The same strategy as that used for DR0705 was pursued for replacing the cysS gene with a cat gene cassette under the control of the constitutively expressed katA promoter (Fig. 1C). However, all colonies screened were heterozygous for chloramphenicol resistance, containing both cysS and cat genes. This result suggests that cysS cannot be deleted from D. radiodurans R1.

DISCUSSION

The work presented here examined the earlier interpretation (9, 26, 27, 34, 35) of the data on Cys-tRNACys formation in archaea. In vitro evidence has clearly shown that the ProRS enzymes from all three domains of life can charge cysteine to tRNA (1, 2). Even though the ProRS enzymes lack the amino acid landscape of the extremely conserved cysteine binding pocket of the canonical CysRS enzymes (30), the crystal structure of M. thermautotrophicus ProRS showed efficient binding of cysteine to the active site of the enzyme (22). However, the specificity for cognate tRNA prevails, and ProRS generates misacylated Cys-tRNAPro, which is not edited by the enzyme (1, 2, 4, 27).

Thus, we looked for an explanation for the successful in vivo rescue of the temperature-sensitive cysS phenotype by complementation with archaeal proS genes (9, 35). It had already been reported (7, 38) that rescue of a temperature-sensitive aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase phenotype can occur through factors other than the wild-type gene product. For instance, partial suppression of a temperature-sensitive E. coli valyl-tRNA synthetase strain by ribosomal protein mutations was reported (7, 38). Such mutations or metabolic changes slow down the growth rate suitably so that the mutant synthetase at the nonpermissive temperature is able to provide sufficient aminoacyl-tRNA for adequate protein synthesis and cell survival. Stabilization of the mutant CysRS in strain UQ818 through increased cysteine levels or through interactions with other proteins may yield the same result. Therefore, the inability of archaeal proS genes to restore viability to the E. coli ΔcysS strain indicates that archaeal proS genes do not generate Cys-tRNACys, at least in E. coli. While all of the published data combined do not rule out the possibility that ProRS synthesizes some correctly charged Cys-tRNA, the conclusion (9, 35) that ProRS can form Cys-tRNACys in vivo is not established. Therefore, we assume that archaeal ProRS does not supply Cys-tRNACys in M. jannaschii. Whether this enzyme can provide this function with the help of an additional protein(s) is an open question (25).

The above findings may also explain the observation that the D. radiodurans DR0705 gene rescued the temperature-sensitive phenotype of strain UQ818 (15), even though this gene did not restore the growth of the E. coli ΔcysS strain. The fact that the DR0705 gene can be deleted from D. radiodurans without any effect on growth shows that its gene product is not required for the viability of the organism. However, attempts to delete the canonical cysS gene did not result in a viable strain, suggesting that CysRS is indeed a required enzyme in D. radiodurans. Unfortunately, genetic methods to establish unambiguously the essentiality of a gene do not yet exist for D. radiodurans.

Although the product of M. jannaschii MJ1477 ORF cysteinylates the homologous tRNA with cysteine in vitro (15), the nature of this protein as CysRS has been questioned by extensive computational analyses that instead predict a secreted polygalactosaminidase or a related polysaccharide hydrolase (21, 28). Moreover, no MJ1477 orthologs are present in the completed genome sequences of the methanogens M. thermautotrophicus (33) and M. maripaludis (Leigh, unpublished); the former organism contains no canonical cysS gene, while a viable cysS deletion strain of M. maripaludis exists (36). Therefore, MJ1477 cannot explain the lack of cysS in M. thermautotrophicus. Given the results of the different lines of experimentation, it cannot be convincingly deduced that the MJ1477 and DR0705 proteins function as CysRS enzymes.

All of these data compel us to conclude that the mechanism of Cys-tRNACys formation in M. jannaschii is still unknown.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Sotiria Palioura, Veronica Liu, and Anjana Agarwal for help with some experiments.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (to D.S.), the Department of Energy (to J.R.B. and D.S.), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (to D.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahel, I., C. Stathopoulos, A. Ambrogelly, A. Sauerwald, H. Toogood, T. Hartsch, and D. Söll. 2002. Cysteine activation is an inherent in vitro property of prolyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34743-34748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrogelly, A., I. Ahel, C. Polycarpo, S. Bunjun-Srihari, B. Krett, C. Jacquin-Becker, B. Ruan, C. Köhrer, C. Stathopoulos, U. L. RajBhandary, and D. Söll. 2002. Methanocaldococcus jannaschii prolyl-tRNA synthetase charges tRNAPro with cysteine. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34749-34754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battista, J. R. 1997. Against all odds: the survival strategies of Deinococcus radiodurans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:203-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beuning, P. J., and K. Musier-Forsyth. 2001. Species-specific differences in amino acid editing by class II prolyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:30779-30785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohman, K., and L. A. Isaksson. 1979. Temperature-sensitive mutants in cysteinyl-tRNA ligase of E. coli K-12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 176:53-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckel, P., W. Piepersberg, and A. Böck. 1976. Suppression of temperature-sensitive aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase mutations by ribosomal mutations: a possible mechanism. Mol. Gen. Genet. 149:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bult, C. J., O. White, G. J. Olsen, L. Zhou, R. D. Fleischmann, G. G. Sutton, J. A. Blake, L. M. FitzGerald, R. A. Clayton, J. D. Gocayne, A. R. Kerlavage, B. A. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, M. D. Adams, C. I. Reich, R. Overbeek, E. F. Kirkness, K. G. Weinstock, J. M. Merrick, A. Glodek, J. L. Scott, N. S. Geoghagen, and J. C. Venter. 1996. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii. Science 273:1058-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunjun, S., C. Stathopoulos, D. Graham, B. Min, M. Kitabatake, A. L. Wang, C. C. Wang, C. P. Vivares, L. M. Weiss, and D. Söll. 2000. A dual-specificity aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase in the deep-rooted eukaryote Giardia lamblia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12997-13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denk, D., and A. Böck. 1987. l-Cysteine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence and expression of the serine acetyltransferase (cysE) gene from the wild-type and a cysteine-excreting mutant. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:515-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVito, J. A., J. A. Mills, V. G. Liu, A. Agarwal, C. F. Sizemore, Z. Yao, D. M. Stoughton, M. G. Cappiello, M. D. Barbosa, L. A. Foster, and D. L. Pompliano. 2002. An array of tartget-specific screening strains for antibacterial discovery. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:478-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Döring, V., H. D. Mootz, L. A. Nangle, T. L. Hendrickson, V. de Crécy-Lagard, P. Schimmel, and P. Marlière. 2001. Enlarging the amino acid set of Escherichia coli by infiltration of the valine coding pathway. Science 292:501-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earl, A. M., S. K. Rankin, K. P. Kim, O. N. Lamendola, and J. R. Battista. 2002. Genetic evidence that the uvsE gene product of Deinococcus radiodurans R1 is a UV damage endonuclease. J. Bacteriol. 184:1003-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriani, G., G. Dirheimer, and J. Gangloff. 1991. Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase: determination of the last E. coli aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase primary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:265-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabrega, C., M. A. Farrow, B. Mukhopadhyay, V. de Crécy-Lagard, A. R. Ortiz, and P. Schimmel. 2001. An aminoacyl tRNA synthetase whose sequence fits into neither of the two known classes. Nature 411:110-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funayama, T., I. Narumi, M. Kikuchi, S. Kitayama, H. Watanabe, and K. Yamamoto. 1999. Identification and disruption analysis of the recN gene in the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mutat. Res. 435:151-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzman, L., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoess, R. H., M. Ziese, and N. Sternberg. 1982. P1 site-specific recombination: nucleotide sequence of the recombining sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:3398-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horton, R. M., H. D. Hunt, S. N. Ho, J. K. Pullen, L., and R. Pease. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou, Y. M., K. Shiba, C. Mottes, and P. Schimmel. 1991. Sequence determination and modeling of structural motifs for the smallest monomeric aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:976-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyer, L. M., L. Aravind, P. Bork, K. Hofmann, A. R. Mushegian, I. B. Zhulin, and E. V. Koonin. 2001. Quod erat demonstrandum? The mystery of experimental validation of apparently erroneous computational analyses of protein sequences. Genome Biol. 2:RESEARCH0051. [Online.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kamtekar, S., W. D. Kennedy, J. Wang, C. Stathopoulos, D. Söll, and T. A. Steitz. 2003. The structural basis of cysteine aminoacylation of tRNAPro by prolyl-tRNA synthetases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1673-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komatsoulis, G. A., and J. Abelson. 1993. Recognition of tRNACys by Escherichia coli cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 32:7435-7444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, T., D. E. Graham, C. Stathopoulos, P. J. Haney, H. S. Kim, U. Vothknecht, M. Kitabatake, K. W. Hong, G. Eggertsson, A. W. Curnow, W. Lin, I. Celic, W. Whitman, and D. Söll. 1999. Cysteinyl-tRNA formation: the last puzzle of aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. FEBS Lett. 462:302-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipman, R. S., J. Chen, C. Evilia, O. Vitseva, and Y. M. Hou. 2003. Association of an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase with a putative metabolic protein in archaea. Biochemistry 42:7487-7496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipman, R. S., K. R. Sowers, and Y. M. Hou. 2000. Synthesis of cysteinyl-tRNACys by a genome that lacks the normal cysteine-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 39:7792-7798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipman, R. S., J. Wang, K. R. Sowers, and Y. M. Hou. 2002. Prevention of mis-aminoacylation of a dual-specificity aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 315:943-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makarova, K. S., and E. V. Koonin. 2003. Comparative genomics of archaea: how much have we learned in six years, and what's next? Genome Biol. 4:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motorin, Y., and J. P. Waller. 1998. Purification and properties of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase from rabbit liver. Biochimie 80:579-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newberry, K. J., Y. M. Hou, and J. J. Perona. 2002. Structural origins of amino acid selection without editing by cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase. EMBO J. 21:2778-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed., p. 1.75-1.81. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 32.Slesarev, A. I., K. V. Mezhevaya, K. S. Makarova, N. N. Polushin, O. V. Shcherbinina, V. V. Shakhova, G. I. Belova, L. Aravind, D. A. Natale, I. B. Rogozin, R. L. Tatusov, Y. I. Wolf, K. O. Stetter, A. G. Malykh, E. V. Koonin, and S. A. Kozyavkin. 2002. The complete genome of hyperthermophile Methanopyrus kandleri AV19 and monophyly of archaeal methanogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4644-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, D. R., L. A. Doucette-Stamm, C. Deloughery, H. Lee, J. Dubois, T. Aldredge, R. Bashirzadeh, D. Blakely, R. Cook, K. Gilbert, D. Harrison, L. Hoang, P. Keagle, W. Lumm, B. Pothier, D. Qiu, R. Spadafora, R. Vicaire, Y. Wang, J. Wierzbowski, R. Gibson, N. Jiwani, A. Caruso, D. Bush, H. Safer, D. Patwell, S. Prabhakar, S. McDougall, G. Shimer, A. Goyal, S. Pietrokovski, G. M. Church, C. J. Daniels, I. J. Mao, P. Rice, J. Nölling, and J. N. Reeve. 1997. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J. Bacteriol. 179:7135-7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stathopoulos, C., C. Jacquin-Becker, H. D. Becker, T. Li, A. Ambrogelly, R. Longman, and D. Söll. 2001. Methanococcus jannaschii prolyl-cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase possesses overlapping amino acid binding sites. Biochemistry 40:46-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stathopoulos, C., T. Li, R. Longman, U. C. Vothknecht, H. D. Becker, M. Ibba, and D. Söll. 2000. One polypeptide with two aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase activities. Science 287:479-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stathopoulos, C., W. Kim, T. Li, I. Anderson, B. Deutsch, S. Palioura, W. Whitman, and D. Söll. 2001. Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase is not essential for viability of the archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14292-14297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Studier, F. W., and B. A. Studier. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189:113-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wittmann, H. G., G. Stöffler. 1975. Alteration of ribosomal proteins in revertants of a valyl-tRNA synthetase mutant of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 141:317-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu, D., H. M. Ellis, E. C. Lee, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and D. L. Court. 2000. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]