Abstract

The Bacillus subtilis genome encodes 16 penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), some of which are involved in synthesis of the spore peptidoglycan. The pbpI (yrrR) gene encodes a class B PBP, PBP4b, and is transcribed in the mother cell by RNA polymerase containing σE. Loss of PBP4b, alone and in combination with other sporulation-specific PBPs, had no effect on spore peptidoglycan structure.

During bacterial endospore formation, two cells cooperate to produce a single dormant spore. Engulfment of the smaller cell, the forespore, by the larger mother cell results in the forespore being surrounded by two opposed membranes. A specialized peptidoglycan (PG) cell wall is synthesized in the intermembrane space (reviewed in reference 17), and this wall plays a key role in maintaining spore dormancy and heat resistance. Synthesis of the innermost PG layer, the germ cell wall, involves forespore-produced enzymes (12), while synthesis of the outer 80 to 90% of the spore PG, the cortex, is carried out by mother cell-expressed enzymes (5). The germ cell wall appears to serve as a template for synthesis of the cortex (12) and serves as the initial cell wall of a germinating spore (3), whereas the cortex is rapidly degraded during spore germination. The proteins involved in PG polymerization, the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), can be divided into three classes based upon domain structures and enzymatic activities (8). Bacillus subtilis possesses six genes that encode class B PBPs (7), proteins that frequently play roles in determining specific PG morphology, such as the rod shape or septum production (reviewed in reference 8). A class B PBP encoded by spoVD is mother cell specific and is required for cortex PG synthesis (5). We present here evidence that the product of yrrR is another mother cell-specific class B PBP, but that this protein plays no clear role in spore PG synthesis.

Identification of the yrrR product.

A sequence alignment of the yrrR product using the tBLASTN software (1) revealed that the most similar proteins are class B PBPs, including B. subtilis SpoVD (27% identical and 42% similar) and Escherichia coli PBP3 (22% identical and 38% similar). SpoVD is transcribed in the mother cell and is required for synthesis of the spore cortex (5), while E. coli PBP3, the product of pbpB (ftsI), is essential for synthesis of septal PG during cell division (23). The gene names pbpA through pbpH have been assigned to other B. subtilis PBP-encoding genes, so we will refer to yrrR as pbpI from this point on.

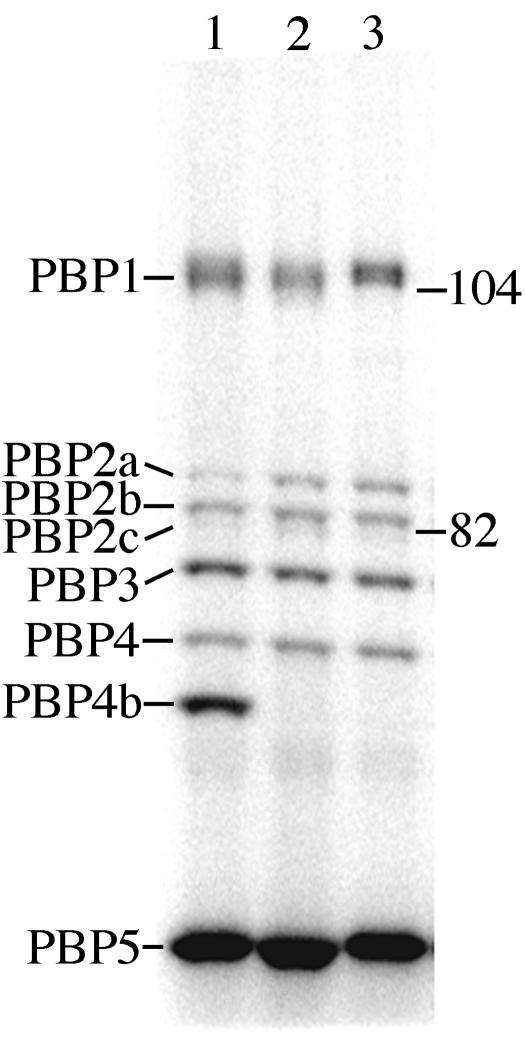

We PCR amplified the coding sequence of pbpI and inserted it into the plasmid pSWEET (4) to produce pDPV146 (Tables 1 to 3), which contains a xylose-inducible expression system and can integrate into the B. subtilis chromosome at the amyE locus. Radioactively labeled penicillin was used to visualize the PBPs present in membranes prepared from xylose-induced DPVB210 (amyE::xylAp-pbpI), DPVB213 (amyE::xylAp-bgaB as a control), and PS832 (wild type) (Fig. 1). In DPVB210, we identified a new PBP with an apparent mass of 65 kDa, which matches the predicted molecular mass of the pbpI product (64.8 kDa). To follow the convention of naming PBPs based upon their migration during denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, we will refer to this protein as PBP4b, since it runs slightly faster than PBP4. PBP4a, which runs in a similar position but is not visible under these growth conditions, is encoded by the dacC gene (15).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypeb | Constructionc | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPVB45 | ΔpbpG::Kn | 12 | |

| DPVB56 | ΔpbpF::Erm ΔpbpG::Kn | 12 | |

| DPVB64 | spoVD::Kn | Laboratory stock (5) | |

| DPVB160 | ΔpbpI::Erm | pDPV114→PS832 | This work |

| DPVB169 | pbpI-lacZ | pDPV126→PS832 | This work |

| DPVB176 | ΔpbpI::Erm spoVD::Kn | DPVB160→DPVB64 | This work |

| DPVB183 | pbpI-lacZ | DPVB169→PY79 | This work |

| DPVB184 | pbpI-lacZ spoIIAC1 | DPVB169→SC1159 | This work |

| DPVB185 | pbpI-lacZ spoIIGB::Tn917Ωnv325 | DPVB169→SC137 | This work |

| DPVB186 | pbpI-lacZ spoIIIGΔ1 | DPVB169→SC500 | This work |

| DPVB198 | ΔpbpG::Kn ΔpbpI::Erm | DPVB45→DPVB160 | This work |

| DPVB199 | pbpF::Cm ΔpbpI::Erm | PS1838→DPVB160 | This work |

| DPVB200 | pbpF::Cm ΔpbpG::Kn ΔpbpI::Erm | PS1838→DPVB199 | This work |

| DPVB210 | xylAp-pbpl at amyE | pDPV146→PS832 | This work |

| DPVB213 | xylAp-bgaB at amyE | pSWEET-bgaB→PS832 | This work |

| PS832 | Wild-type, Trp+ revertant of 168 | Laboratory stock | |

| PS1838 | pbpF::Cm | 21 | |

| PY79a | Wild type | 16, 24 | |

| SC137a | spoIIGB::Tn917Ωnv325 | S. Cutting (16) | |

| SC500a | spoIIIGΔ1 | S. Cutting (16) | |

| SC1159a | spoIIAC1 | S. Cutting (16) |

The genetic background is PY79. The other strains' genetic background is PS832.

Antibiotic resistance abbreviations: Cm, chloramphenicol; Erm, lincomycin and erythromycin; Kn, kanamycin.

The designation preceding the arrow indicates the source of donor DNA in a natural transformation of the recipient strain following the arrow.

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| pbpI1 | 5′AGAGGGCCGCGTGACGACTCTTG | Anneals 345 bp upstream of pbpI |

| pbpI2 | 5′ATCAGAGTCAGAAGACTTCTCAG | Anneals 355 bp downstream of pbpI |

| pbpI3 | 5′CGGGATCCTTAACATGTGCTGAGAAGTTG | Places a BamHI site 26 bp downstream of pbpI |

| pbpI5 | 5′GCGCTTAATTAACACAATGTGGGTGAGGTGTTT | Places a PacI site 25 bp upstream of pbpI |

| pbpIa | 5′CGGAATTCAGAGGGCCGCGTGACGACTCTTG | Places an EcoRI site 345 bp upstream of pbpI |

Underlined bases are restriction sites.

FIG. 1.

Identification of PbpI (PBP4b). Strains were grown in 2× SG medium (10) at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1. Xylose was then added to a final concentration of 2%, and incubation was continued until the optical density reached 1.0. Cell membranes were prepared as previously described (19). PBPs were detected with 125I-labeled penicillin X as previously described (11, 12). Proteins were separated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and PBPs were detected with a STORM 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Lanes: 1, DPVB210 (over-expressed pbpI); 2, DPVB213 (overexpressed bgaB); 3, PS832 (wild-type). PBPs are indicated on the left and are numbered as previously described (2). The migration positions of molecular mass markers (Bio-Rad low-range, prestained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis standards) are indicated on the right in kilodaltons.

Expression of pbpI.

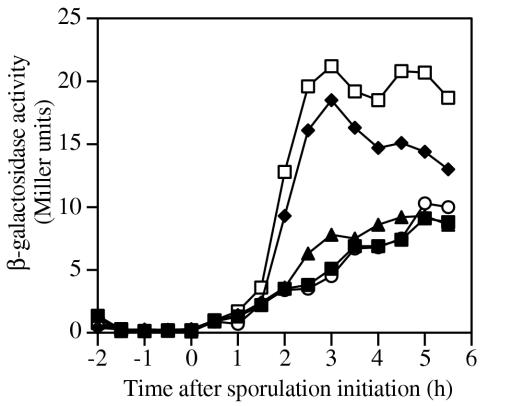

A pbpI-lacZ transcriptional fusion was constructed in pDPV126 (Table 1) and inserted into the B. subtilis chromosome via a single-crossover recombination. No β-galactosidase was detected in vegetative cells and outgrowing spores (data not shown). Expression of pbpI began 1 to 2 h after the initiation of sporulation (Fig. 2), and the level of expression was very low compared to those of several other PBP-encoding genes (20-22). Based on this timing of expression, we predicted that pbpI was transcribed under the control of σE or σF. Mutations in spoIIAC (encoding σF) and spoIIGB (encoding σE) completely abolished pbpI-lacZ expression, while a null mutation in spoIIIG (encoding σG) had no effect on the timing and level of expression (Fig. 2). This pattern is consistent with transcription by σE RNA polymerase holoenzyme. The pbpI (yrrR) gene was also recently identified in a transcription-profiling search for σE-dependent genes, and putative σE recognition sequences were located 50 bp upstream of the pbpI start codon (6). Active σE also drives expression of a gene starting 64 bp downstream of the pbpI start codon, yrrS (6), and these genes may constitute an operon; however, cotranscription has not been demonstrated.

FIG. 2.

Expression of pbpI. Growth and sporulation were in 2× SG medium (▪) at 37°C. Strain PY79 (▪) contained no lacZ fusion and revealed the background activity. The expression of pbpI-lacZ was assayed with o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as described previously (14) in the wild-type background (♦, DPVB183) and in isogenic spoIIAC (sigF) (○, DPVB184), spoIIGB (sigE) (▴, DPVB185), and spoIIIG (sigG) (□, DPVB186) mutants.

Phenotypic properties of pbpI mutant strains.

We constructed a mutant strain in which 89% of the pbpI coding sequence (codons 4 to 525 out of 584, including the conserved penicillin-binding active site) was deleted and replaced with an erythromycin resistance gene cassette (DPVB160, Table 1). This mutation may have a polar effect on expression of yrrS, if pbpI and yrrS constitute an operon. PBPs of the same class frequently exhibit functional redundancy, so we also constructed a double-mutant strain lacking pbpI and spoVD, the only other class B PBP-encoding gene specifically expressed during sporulation (5). Two genes encoding class A PBPs, pbpF and pbpG, are expressed specifically within the forespore, and a pbpF pbpG double mutant produces defective spore PG. We constructed double and triple mutants lacking pbpF, pbpG, and pbpI to examine the effects on spore PG synthesis. Phenotypic properties, including growth rate, cell morphology, sporulation efficiency, PG structures of both the vegetative cell and spore cortex, spore heat resistance, spore germination rate, and the rate of spore outgrowth, were studied.

There were no significant differences between the growth rates and vegetative cell morphologies of any of the mutant strains and the wild type. The pbpI, pbpF pbpI, and pbpG pbpI strains produced as many chloroform-resistant (10% chloroform, 10 min) and heat-resistant spores (80°C, 10 min) per ml of culture as the wild type. To measure spore heat resistance precisely, spores were purified, heated in water at 80°C for various times, and plated to determine the number of surviving CFU per milliliter. There was no significant difference among the spore killing rates of these strains. In addition, the germination and outgrowth kinetics of the mutant spores were indistinguishable from those of the wild type (data not shown). PG was purified from each of the spore preparations, and muropeptides obtained from the PG were analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (18). The overall structures of the spore PGs of the pbpI, pbpI pbpF, and pbpI pbpG mutant strains were indistinguishable from those of the wild-type and single-mutant strains (Table 4, 48-h samples).

TABLE 4.

Structural parameters of dormant spore and forespore PG

| Strain | Genotype | Time in sporulation (h) | % Muramic acid with side chain:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactam | Alanine | Tripeptide | Tetrapeptide | Cross-linked | |||

| PS832 | Wild type | 48 | 49.4 | 20.4 | 1.4 | 28.9 | 3.1 |

| PS1838 | ΔpbpF::Cm | 48 | 49.8 | 19.4 | 0.8 | 29.9 | 3.2 |

| DPVB45 | ΔpbpG::Kn | 48 | 49.1 | 20.3 | 1.7 | 28.9 | 3.3 |

| DPVB160 | ΔpbpI::Erm | 48 | 49.3 | 16.7 | 1.3 | 32.7 | 3.6 |

| DPVB198 | ΔpbpG::Kn ΔpbpI::Erm | 48 | 48.6 | 18.1 | 1.3 | 32.0 | 3.4 |

| DPVB199 | ΔpbpF::Cm ΔpbpI::Erm | 48 | 49.5 | 18.1 | 1.0 | 31.4 | 3.3 |

| PS832 | Wild type | 8 | 45.4 | 27.5 | 4.0 | 23.1 | 2.8 |

| DPVB160 | ΔpbpI::Erm | 8 | 44.7 | 29.7 | 4.4 | 21.1 | 2.7 |

| DPVB64 | spoVD::Kn | 8 | 8.6 | 20.8 | 50.1 | 20.5 | 2.2 |

| DPVB176 | ΔpbpI::Erm spoVD::Kn | 8 | 9.1 | 24.0 | 43.3 | 23.6 | 2.2 |

| DPVB56 | ΔpbpF::Cm ΔpbpG::Kn | 8 | 14.4 | 5.4 | 12.1 | 68.1 | 11.0 |

| DPVB200 | ΔpbpF::Cm ΔpbpG::Kn ΔpbpI::Erm | 8 | 12.9 | 4.6 | 11.1 | 71.4 | 11.5 |

The spoVD and pbpF pbpG strains produce extremely few spores, so no difference in sporulation efficiency could be seen when the pbpI mutation was introduced into these backgrounds, and spore phenotypic properties could not be assessed. However, forespore PG synthesis during sporulation was analyzed (13) in cultures of a pbpI single mutant (DPVB160), a pbpI spoVD double mutant (DPVB176), and a pbpI pbpF pbpG triple mutant (DPVB200) and compared to that of the wild-type (PS832), spoVD (DPVB64), and pbpF pbpG (DPVB56) strains, respectively. The amount of spore PG produced during sporulation was assayed by determination of the muramic acid content of culture samples. There were no significant differences between the strains in each pair (data not shown). The PG structural analyses demonstrated that throughout sporulation (Table 4, 8-h samples) (data not shown), the pbpI strain produced spore PG with structural parameters similar to those found in the wild type. The pbpI spoVD strain produced spore PG with structural parameters similar to those found in the spoVD strain—essentially a small amount of germ cell wall PG. The pbpI pbpF pbpG triple mutant produced spore PG with structural parameters similar to those found in the pbpF pbpG strain (12).

The pbpI gene encodes a previously unidentified sporulation-specific PBP. PBP4b is expressed in the mother cell during sporulation, under the control of σE. We could find no reproducible structural differences between the spore PG produced by a pbpI mutant and that produced by a wild-type strain. In addition, we found no effects of pbpI on the limited amount of abnormal spore PG produced in pbpF pbpG and spoVD strains. We conclude that either PBP4b plays no significant role in spore PG synthesis or other PBPs carry out redundant functions, masking any effects of the loss of PBP4b.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Construction | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pDG646 | Vector carrying Erm cassette | 9 |

| pDPC87 | Transcriptional lacZ fusion vector | 21 |

| pDPV107 | PCR fragment using primers pbpI1 and pbpI2 inserted into pGEM-T (Promega) | |

| pDPV114 | SmaI-HindIII fragment of pDG646 inserted into EcoRV-HindIII-digested pDPV107, replacing 89% of pbpI with Erm cassette | |

| pDPV126 | PCR fragment using primers pbpIa and pbpI2 cut with EcoRI and HindIII, with 975-bp fragment inserted into EcoRI-HindIII-digested pDPC87 | |

| pDPV146 | PCR fragment using primers pbpI3 and pbpI5 inserted into PacI-BamHI-digested pSWEET-bgaB | |

| pSWEET-bgaB | 4 |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant GM56695 (D.L.P) from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Peter and Barbara Setlow for providing strains, Amanda Dean for technical assistance, and Marita Seppanen Popham for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atrih, A., and S. J. Foster. 2001. Analysis of the role of bacterial endospore cortex structure in resistance properties and demonstration of its conservation amongst species. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91:364-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atrih, A., P. Zöllner, G. Allmaier, M. P. Williamson, and S. J. Foster. 1998. Peptidoglycan structural dynamics during germination of Bacillus subtilis 168 endospores. J. Bacteriol. 180:4603-4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhavsar, A. P., X. Zhao, and E. D. Brown. 2001. Development and characterization of a xylose-dependent system for expression of cloned genes in Bacillus subtilis: conditional complementation of a teichoic acid mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:403-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel, R. A., S. Drake, C. E. Buchanan, R. Scholle, and J. Errington. 1994. The Bacillus subtilis spoVD gene encodes a mother-cell-specific penicillin-binding protein required for spore morphogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 235:209-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichenberger, P., S. T. Jensen, E. M. Conlon, C. van Ooij, J. Silvaggi, J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, M. Fujita, S. Ben-Yehuda, P. Stragier, J. S. Liu, and R. Losick. 2003. The sigmaE regulon and the identification of additional sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 327:945-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster, S. J., and D. L. Popham. 2002. Structure and synthesis of cell wall, spore cortex, teichoic acids, S-layers, and capsules, p. 21-41. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its close relatives: from genes to cells. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Goffin, C., and J.-M. Ghuysen. 1998. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1079-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guérout-Fleury, A.-M., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167:335-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leighton, T. J., and R. H. Doi. 1971. The stability of messenger ribonucleic acid during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 254:3189-3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masson, J. M., and R. Labia. 1983. Synthesis of a 125I-radiolabeled penicillin for penicillin-binding proteins studies. Anal. Biochem. 128:164-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPherson, D. C., A. Driks, and D. L. Popham. 2001. Two class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins of Bacillus subtilis play redundant roles in sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 183:6046-6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meador-Parton, J., and D. L. Popham. 2000. Structural analysis of Bacillus subtilis spore peptidoglycan during sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 182:4491-4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson, W. L., and P. Setlow. 1990. Sporulation, germination, and outgrowth, p. 391-450. In C. R. Harwood and S. M. Cutting (ed.), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 15.Pedersen, L. B., T. Murray, D. L. Popham, and P. Setlow. 1998. Characterization of dacC, which encodes a new low-molecular-weight penicillin-binding protein in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:4967-4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen, L. B., K. Ragkousi, T. J. Cammett, E. Melly, A. Sekowska, E. Schopick, T. Murray, and P. Setlow. 2000. Characterization of ywhE, which encodes a putative high-molecular-weight class A penicillin-binding protein in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 246:187-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popham, D. L. 2002. Specialized peptidoglycan of the bacterial endospore: the inner wall of the lockbox. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 59:426-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popham, D. L., J. Helin, C. E. Costello, and P. Setlow. 1996. Analysis of the peptidoglycan structure of Bacillus subtilis endospores. J. Bacteriol. 178:6451-6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popham, D. L., B. Illades-Aguiar, and P. Setlow. 1995. The Bacillus subtilis dacB gene, encoding penicillin-binding protein 5*, is part of a three-gene operon required for proper spore cortex synthesis and spore core dehydration. J. Bacteriol. 177:4721-4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popham, D. L., and P. Setlow. 1995. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis ponA operon, which codes for penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 1 and a PBP-related factor. J. Bacteriol. 177:326-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popham, D. L., and P. Setlow. 1993. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pbpF gene, which codes for a putative class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 175:4870-4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popham, D. L., and P. Setlow. 1994. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, mutagenesis, and mapping of the Bacillus subtilis pbpD gene, which codes for penicillin-binding protein 4. J. Bacteriol. 176:7197-7205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spratt, B. G. 1975. Distinct penicillin-binding proteins involved in the division, elongation, and shape of Escherichia coli K12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:2999-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youngman, P., J. B. Perkins, and K. Sandman. 1984. New genetic methods, molecular cloning strategies, and gene fusion techniques for Bacillus subtilis which take advantage of Tn917 insertional mutagenesis, p. 103-111. In J. A. Hoch and A. T. Ganesan (ed.), Genetics and biotechnology of bacilli. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.