The structure of GlnK1, one of three GlnK proteins encoded by the hyperthermophilic archaeon A. fulgidus, was solved to 2.28 Å resolution.

Keywords: PII-like proteins, GlnK, GlnB, signalling

Abstract

GlnB and GlnK are ancient signalling proteins that play a crucial role in the regulation of nitrogen assimilation. Both protein types can be present in the same genome as either single or multiple copies. However, the gene product of glnK is always found in an operon together with an amt gene encoding an ammonium-transport (Amt) protein. Complex formation between GlnK and Amt blocks ammonium uptake and depends on the nitrogen level in the cell, which is regulated through the binding of specific effector molecules to GlnK. In particular, an ammonium shock to a cell culture previously starved in this nitrogen source or the binding of ATP to purified GlnK can stimulate effective complex formation. While the binding of ATP/ADP and 2-oxoglutarate (as a signal for low intracellular nitrogen) to GlnK have been reported and several GlnB/K protein structures are available, essential functional questions remain unanswered. Here, the crystal structure of A. fulgidus GlnK1 at 2.28 Å resolution and a comparison with the crystal structures of other GlnK proteins, in particular with that of its paralogue GlnK2 from the same organism, is reported.

1. Introduction

PII-like proteins such as GlnB and GlnK constitute a family of trimeric cytoplasmic signalling proteins that are found in a wide variety of organisms from prokaryotes to plants. They play a central regulatory role in assimilation of the element nitrogen for biosyntheses and as such they sense and are modulated by the cellular levels of ATP/ADP, 2-oxoglutarate and glutamine (Forchhammer, 2008 ▶; Leigh & Dodsworth, 2007 ▶). While the first three effector molecules can bind directly to the protein, glutamine modulates PII activity indirectly by inducing other enzymes to phosphorylate (Forchhammer & Tandeau de Marsac, 1995 ▶), uridylylate (Bueno et al., 1985 ▶) or adenylylate (Hesketh et al., 2002 ▶) specific amino-acid residues in the protein. In a complex signal-modulation response, PII proteins interact with a broad variety of downstream targets from transcription regulators (Atkinson et al., 1994 ▶; Ninfa & Magasanik, 1986 ▶) to enzymes (Heinrich et al., 2004 ▶; Jiang et al., 1998 ▶, 2007 ▶; Zhang et al., 2001 ▶) and membrane proteins (Coutts et al., 2002 ▶; Gruswitz et al., 2007 ▶; Strösser et al., 2004 ▶). Their ability to integrate a wide range of effector types and concentrations is the subject of extensive and active research. Several crystal structures of PII proteins are currently available (Helfmann et al., 2010 ▶) with and without bound ATP or ADP, highlighting the conserved geometry of the nucleotide-binding pockets at the monomer interfaces and the functional flexibility of the extended T-loop region (residues 36–55) that mediates interaction with the various target proteins. The binding mode of the third effector, 2-oxoglutarate, has remained elusive, with the exception of a single observation in one subunit of Methanococcus jannaschii GlnK1 in which the ketoacid is bound on top of the trimer (Yildiz et al., 2007 ▶). However, very recently a different binding mode was revealed in a PII protein from Azospirillum brasilense, in which the binding of 2-oxoglutarate was only possible after that of MgATP (Truan et al., 2010 ▶). This binding mode was consistently observed in all monomers and explained previous biochemical studies that had identified ATP binding as a necessary prerequisite for the ligation of 2-oxoglutarate (Forchhammer, 2008 ▶; Jiang & Ninfa, 2007 ▶; Ninfa & Jiang, 2005 ▶).

In our characterization of the crystallographic structure and the thermodynamic properties of the PII protein GlnK2 from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Af-GlnK2), we observed that this particular GlnK orthologue failed to bind 2-oxoglutarate in the presence or absence of ATP and ADP, but instead showed a strongly cooperative behaviour for nucleotide binding in isothermal titration calorimetry that had not been observed previously (Helfmann et al., 2010 ▶). A. fulgidus possesses three genes for PII proteins, all of which are found in a genetic context with an ammonium-transport (Amt) protein. Here, we report the three-dimensional structure of Af-GlnK1, which shares 64% amino-acid sequence identity with Af-GlnK2 but shows significantly different ligand-binding properties.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning, expression and purification of Af-GlnK1

The 330 bp glnK1 gene was amplified from A. fulgidus genomic DNA by PCR with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Fermentas), using a forward primer containing an NdeI restriction site (5′-GGCATA TGAAGATGGTTGTCGCTGTAATAAG-3′) and a reverse primer without a stop codon that carried an XhoI restriction site (5′-GACGGGTGAGGAGGAAGTTCTCGAGCC-3′). Ligation of this product into pET21a (Novagen) allowed the expression of Af-GlnK1 with a C-terminal His6 tag. The correctness of the insertion of the gene into the plasmid was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Recombinant protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) Rosetta (Novagen) cells grown in either LB medium or autoinducing ZYM-5052 medium (Studier, 2005 ▶) supplemented with 100 µg l−1 ampicillin at 303 K with continuous agitation (200 rev min−1). The cell-culture density was monitored by the absorbance at 600 nm and GlnK1 expression was analysed by Western blots. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000g, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 193 K until further use. Protein purification followed procedures described elsewhere (Helfmann et al., 2010 ▶), with final protein yields being significantly improved by increasing the exposure of the His6 tag by using a linker consisting of three additional alanine residues. The protein purity was confirmed by SDS–PAGE (Laemmli, 1970 ▶) and quantified using the BCA protein assay (Smith et al., 1985 ▶).

2.2. Site-directed mutagenesis

The addition of three alanine residues between Val109 and the C-terminal His6 tag was achieved by PCR with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Fermentas) and the following forward (plus its corresponding reverse) oligonucleotide primer: 5′-GGACGGGTGAGGAGGAAGTTGCTGCAGCTCTCGAGCACCACCACCACCAC-3′. After an initial denaturation step at 368 K for 30 s, the cycling parameters were 30 s at 368 K followed by 1 min at 328 K and 6 min at 341 K (16 cycles). This reaction mixture was digested with DpnI at 310 K for 1 h before being transformed into E. coli XL10 Gold cells. The presence of the mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

2.3. Crystallization and data collection

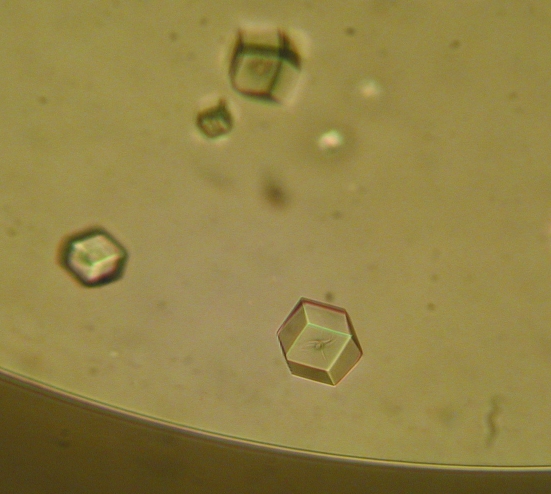

Crystallization experiments were set up at 293 K by sitting-drop vapour diffusion. The best results were achieved using a 3 µl drop consisting of a 2:1 mixture of 5 mg ml−1 protein and a reservoir solution composed of 15%(w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 5000 monomethyl ether and 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer pH 5.5 (Fig. 1 ▶). Single crystals appeared after 2 d and did not grow any further. 10%(v/v) 2R,3R-butanediol was added as a cryoprotectant prior to data collection. Diffraction data sets were collected to a maximum resolution of 2.28 Å using synchrotron radiation at the Swiss Light Source, Villigen, Switzerland. The data were indexed and integrated using MOSFLM (Leslie, 1992 ▶) and scaled using SCALA (Evans, 2006 ▶). Data-collection and refinement statistics are given in Table 1 ▶.

Figure 1.

Crystals of A. fulgidus GlnK1 protein grown at 293 K by the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method in a 3 µl drop consisting of 2 µl 5 mg ml−1 protein solution mixed with 1 µl 15%(w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 5000 monomethyl ether and 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer pH 5.5 reservoir solution. The average crystal size was 150 µm.

Table 1. Summary of crystal parameters, data-collection and refinement statistics for the as-isolated Af-GlnK1 protein.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Crystal data | |

| Space group | I213 |

| No. of monomers in asymmetric unit | 1 |

| Unit-cell parameters | |

| a (Å) | 94.6 |

| α (°) | 90.0 |

| Data-processing statistics | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 33.4–2.28 (2.33–2.28) |

| No. of unique reflections | 6605 (469) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) |

| Multiplicity | 19.7 (20.8) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 23.9 (7.1) |

| Rmerge | 0.094 (0.475) |

| Rp.i.m. | 0.022 (0.108) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 37.6 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| No. of atoms in model | 873 |

| No. of solvent molecules | 74 |

| Final Rcryst | 0.173 |

| Final Rfree | 0.220 |

| R.m.s.d. bond lengths (Å) | 0.023 |

| R.m.s.d. bond angles (°) | 1.953 |

| Mean B factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 33.19 |

| Water | 42.62 |

| Ramachandran plot, residues in | |

| Most favoured regions | 83 [93.3%] |

| Allowed regions | 6 [6.7%] |

| Generously allowed and disallowed regions | 0 [0.0%] |

| PDB code | 3o8w |

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

The structure was solved by molecular replacement with programs from the CCP4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶) using Af-GlnK2 (PDB code 3ncp; Helfmann et al., 2010 ▶) as a search model in MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 2010 ▶). The molecular-replacement solution was refined in REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1999 ▶) and provided the first electron-density maps. For refinement, 5% of all reflections were chosen at random and used as a test set for cross-validation (Brünger, 1993 ▶). Subsequent steps of model building were carried out using Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶) and refinement was performed using REFMAC. Water molecules were placed automatically with Coot and were then manually edited in subsequent rounds of refinement cycles. For the structural model-refinement statistics, see Table 1 ▶.

2.5. Validation and deposition

Stereochemical analysis of the Af-GlnK1 structure was carried out with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993 ▶). In a Ramachandran plot, all residues were found in the most favoured or additionally allowed regions. The atomic coordinates and structure-factor amplitudes of the final protein model have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession code 3o8w).

3. Results and discussion

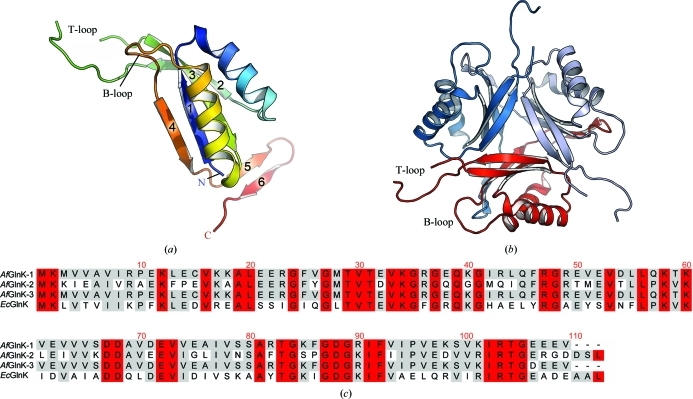

Af-GlnK1 crystallized in the cubic space group I213 with one monomer per asymmetric unit. The structure solved at 2.28 Å resolution reveals the typical fold adopted by PII-family proteins, which consists of two interlocking β–α–β motifs yielding an antiparallel β-sheet with 4-1-3-2 topology (Fig. 2 ▶ a). Strands 2 and 3 are connected by an extended loop region termed the T-loop, which plays a key functional role by interacting directly with the binding partners of the protein when in the active conformation. The binding of different effector molecules leads to conformational changes in the T-loops and different members of the PII protein family have been shown to exhibit varying degrees of binding cooperativity. The highly stable GlnK trimer provides three binding sites for ATP and ADP, each of which is located in the interface between two adjacent monomers and bordered by the B-loop (residues 82–90) and T-loop (residues 36–55) of one monomer plus the C-terminus of the neighbouring monomer. As in most other PII structures, the T-loop is partially disordered in Af-GlnK1 and consequently residues 44–53 were not included in the structural model (Figs. 2 ▶ a and 2 ▶ b).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of GlnK1. (a) Cartoon diagram of the A. fulgidus GlnK1 monomer coloured from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus). The inner core of the protein is composed of four antiparallel β-strands surrounded by two α-helices. The protruding T-loop located between strands 2 and 3 is partially disordered and residues 44–53 were therefore not modelled. (b) View along the threefold axis of the physiological trimer of the protein. (c) Sequence alignment of the three GlnK proteins from A. fulgidus with that from E. coli; residues that share 100–80% and 79–50% identity are shown in red and grey, respectively.

The T-loop is the part of the GlnK protein that interacts with its cognate Amt protein by inserting deeply into the three substrate channels of the Amt trimer from the cytoplasmic side. This binding mode was predicted on the basis of the structure of A. fulgidus Amt1 (Andrade et al., 2005 ▶). Subsequent crystallographic characterization of the AmtB–GlnK complex from E. coli (Conroy et al., 2007 ▶; Gruswitz et al., 2007 ▶) and single-particle electron microscopy of the Amt–GlnK complex from M. jannaschii (Yildiz et al., 2007 ▶) confirmed that residue Arg47, which is fully conserved in GlnK proteins, is crucial for this interaction. In A. fulgidus, the transporter/regulator pairs Amt1/GlnK1 and Amt3/GlnK3 are closely related and are found in two separate operons. However, the amt3glnK3 operon additionally contains a third transport system encoded by amt2 and glnK2, indicating the co-translation and co-regulation of two distinct ammonium transporters. While the Amt proteins Amt2 and Amt3 both contain all of the signature residues and features found in this class of proteins, the functional difference may reside in the regulatory GlnK proteins. Previous studies of Af-GlnK2 unexpectedly revealed that the protein does not bind 2-oxoglutarate in either the presence or the absence of adenosine nucleotides. Moreover, distinct cooperative binding patterns for ATP versus ADP were detected by isothermal titration calorimetry, with a strong binding preference for ATP (Helfmann et al., 2010 ▶). From the structure of the protein, however, this obvious functional difference with respect to other GlnK proteins could not be fully comprehended. Af-GlnK1 is highly similar in structure to Af-GlnK2 (Fig. 3 ▶), but preliminary isothermal titration calorimetry data indicate that in this case the binding of either ATP or ADP does not occur cooperatively. A comparative functional analysis of the three GlnK proteins from A. fulgidus is currently under way.

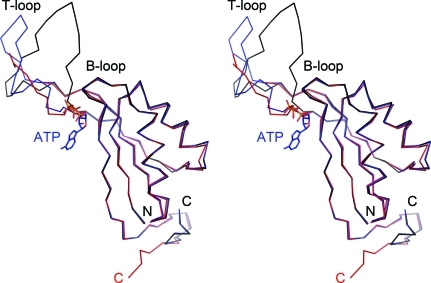

Figure 3.

Structural comparison of Af-GlnK1 and Af-GlnK2. Stereo image of the ligand-free GlnK1 monomer (red) and GlnK2 (ligand-free in black, ATP-bound in blue). The overall very high similarity of the core structures is only disrupted at the T-loop region. Here, although nine residues could not be modelled in GlnK1, a more compact fold for this loop is obviously observed in GlnK1.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: GlnK1, 3o8w

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; grant AN 676/1-1). Diffraction data were collected at the Swiss Light Source, Villigen, Switzerland. We thank Oliver Einsle for stimulating discussions.

References

- Andrade, S. L., Dickmanns, A., Ficner, R. & Einsle, O. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 14994–14999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, M. R., Kamberov, E. S., Weiss, R. L. & Ninfa, A. J. (1994). J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28288–28293. [PubMed]

- Brünger, A. T. (1993). Acta Cryst. D49, 24–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bueno, R., Pahel, G. & Magasanik, B. (1985). J. Bacteriol. 164, 816–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763.

- Conroy, M. J., Durand, A., Lupo, D., Li, X.-D., Bullough, P. A., Winkler, F. K. & Merrick, M. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 1213–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coutts, G., Thomas, G., Blakey, D. & Merrick, M. (2002). EMBO J. 21, 536–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Forchhammer, K. (2008). Trends Microbiol. 16, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Forchhammer, K. & Tandeau de Marsac, N. (1995). J. Bacteriol. 177, 5812–5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gruswitz, F., O’Connell, J. III & Stroud, R. M. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, A., Maheswaran, M., Ruppert, U. & Forchhammer, K. (2004). Mol. Microbiol. 52, 1303–1314. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Helfmann, S., Lü, W., Litz, C. & Andrade, S. L. (2010). J. Mol. Biol. 402, 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, A., Fink, D., Gust, B., Rexer, H. U., Scheel, B., Chater, K., Wohlleben, W. & Engels, A. (2002). Mol. Microbiol. 46, 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P., Mayo, A. E. & Ninfa, A. J. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 4133–4146. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P. & Ninfa, A. J. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 12979–12996. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P., Peliska, J. A. & Ninfa, A. J. (1998). Biochemistry, 37, 12802–12810. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Nature (London), 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291.

- Leigh, J. A. & Dodsworth, J. A. (2007). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 349–377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leslie, A. G. W. (1992). Jnt CCP4/ESF–EACBM Newsl. Protein Crystallogr. 26

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A., Lebedev, A., Wilson, K. S. & Dodson, E. J. (1999). Acta Cryst. D55, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ninfa, A. J. & Jiang, P. (2005). Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ninfa, A. J. & Magasanik, B. (1986). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 5909–5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith, P. K., Krohn, R. I., Hermanson, G. T., Mallia, A. K., Gartner, F. H., Provenzano, M. D., Fujimoto, E. K., Goeke, N. M., Olson, B. J. & Klenk, D. C. (1985). Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Strösser, J., Lüdke, A., Schaffer, S., Krämer, R. & Burkovski, A. (2004). Mol. Microbiol. 54, 132–147. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Studier, F. W. (2005). Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Truan, D., Huergo, L. F., Chubatsu, L. S., Merrick, M., Li, X.-D. & Winkler, F. K. (2010). J. Mol. Biol. 400, 531–539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, O., Kalthoff, C., Raunser, S. & Kühlbrandt, W. (2007). EMBO J. 26, 589–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y., Pohlmann, E. L., Ludden, P. W. & Roberts, G. P. (2001). J. Bacteriol. 183, 6159–6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: GlnK1, 3o8w