Abstract

The growth of a γ-glutamyl aminopeptidase (GGT)-deficient Neisseria meningitidis strain was much slower than that of the parent strain in rat cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and in a synthetic CSF-mimicking medium, and the growth failure was suppressed by the addition of cysteine. These results suggested that, in the environment of cysteine shortage, meningococcal GGT provided an advantage for meningococcal multiplication by supplying cysteine from environmental γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides.

Neisseria meningitidis is a gram-negative diplococcus pathogen that colonizes the nasopharynx of humans as a unique host. It sometimes spreads into the bloodstream, resulting in septicemia, and subsequently induces meningitis when it reaches the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (25).

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT; EC 2.3.2.2) (also called γ-glutamyl aminopeptidase) catalyzes the hydrolysis of γ-glutamyl compounds. In Escherichia coli, it is speculated that GGT contributes to the recycling of exogenous glutathione (γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine [GSH]) (21), and Helicobacter pylori GGT is advantageous for the colonization of notobiotic piglets and mice (6, 13). In N. meningitidis, GGT is used as an identification marker (3, 27). However, the physiological function of meningococcal GGT has not been studied. In the present study, we characterized the physiological function of meningococcal GGT by using in vitro experimental models, owing to the lack of appropriate animal models for meningococcal diseases (1, 14).

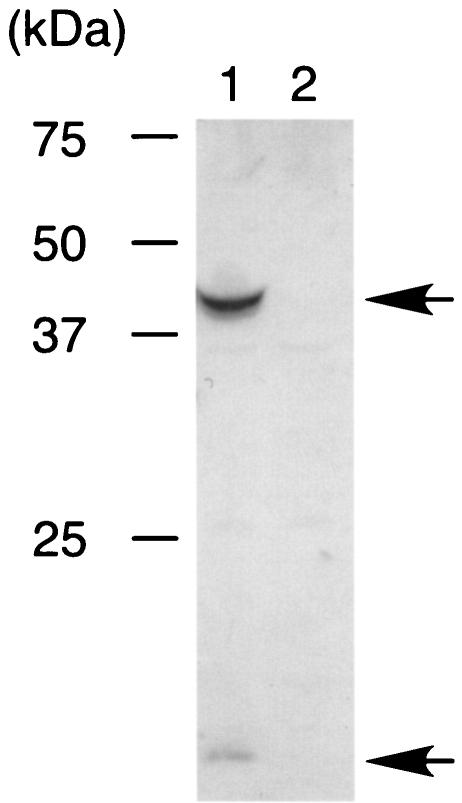

The ggt gene of N. meningitidis strain H44/76 (23) was disrupted by the insertion of a spectinomycin resistance gene by a method described previously (23), resulting in HT1089 (H44/76 Δggt::Spcr). The disruption of the ggt gene in HT1089 was confirmed by the absence of GGT activity in HT1089 extract (data not shown) and by Western blotting using anti-meningococcal GGT rabbit serum (preparation of the antiserum will be described elsewhere) (Fig. 1). In commonly used rich media (e.g., Trypticase soy broth and GC medium [Becton Dickinson]), HT1089 grew as well as the parent strain (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Western blot of N. meningitidis whole-cell extracts with anti-meningococcal GGT rabbit antiserum. Bacterial whole extracts equivalent to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05 were analyzed by Western blotting (23). Lane 1, N. meningitidis strain H44/76; lane 2, the derivative Δggt strain HT1089. The arrows indicate the bands corresponding to the processed small and large subunits of meningococcal GGT.

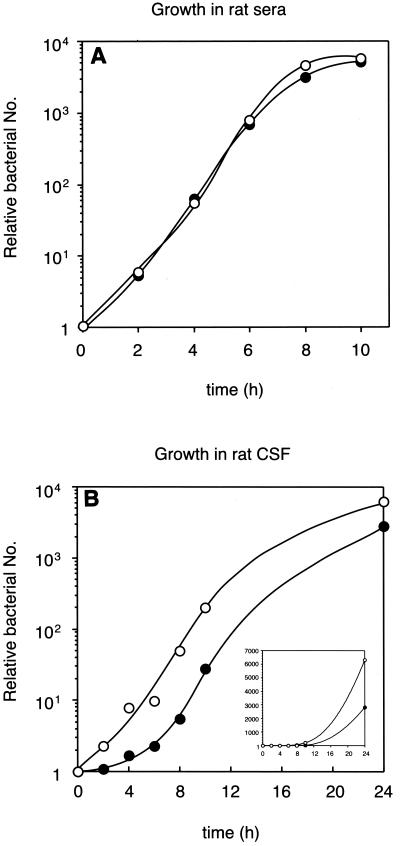

We first examined the role of meningococcal GGT by using in vitro models as follows: (i) adhesion to or invasion into cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and epithelial cells (Hep-2 and A549 cells), (ii) survival against complements in normal human sera, and (iii) growth in inactivated rat sera. No differences between HT1089 and H44/76 for these phenotypes were observed (Fig. 2A and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Growth of N. meningitidis strains in rat sera (A) and CSF (B). (A) Approximately 8 × 102 bacteria were incubated in 40 μl of heat-inactivated rat sera at 37°C. The sera were buffered with 17 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) and supplemented with 100 μM Fe2(SO4)3 to complement the loss of the red cells, whose hemoglobin is the major source of ferric iron for the growth of Neisseria (18). (B) Approximately 102 bacteria were incubated in 10 μl of heat-inactivated rat CSF buffered with 17 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) at 37°C. The number of bacteria was continuously monitored by plating appropriate dilutions on GC agar plates. The relative bacterial number is shown by the ratio of the number of bacteria at the indicated time to that at time zero. A representative result from at least four experiments with similar results is shown. The open and solid circles correspond to the wild-type N. meningitidis strain H44/76 and the derivative Δggt strain HT1089, respectively. The scale in the inset is shown as nonlogarithmic numbers.

CSF is a critical environment for the infection and multiplication of bacteria that cause meningitis in humans. It has been shown that Streptococcus pneumoniae multiplies in CSF after 24 h of infection in the rat meningitis model (16). We examined the multiplication of N. meningitidis strains in CSF in vitro. For this experiment, we used sterile, pooled, heat-inactivated rat CSF instead of human CSF because the quality of the rat CSF can be more easily controlled and the amounts of its components, such as amino acids, are largely similar to those of human CSF (2, 9, 11, 12, 15, 28). When N. meningitidis strains were cultured in CSF, a growth defect of HT1089 was clearly observed compared to its growth in heat-inactivated rat sera (Fig. 2). This result strongly suggested that the meningococcal GGT provided an advantage for meningococcal multiplication in CSF.

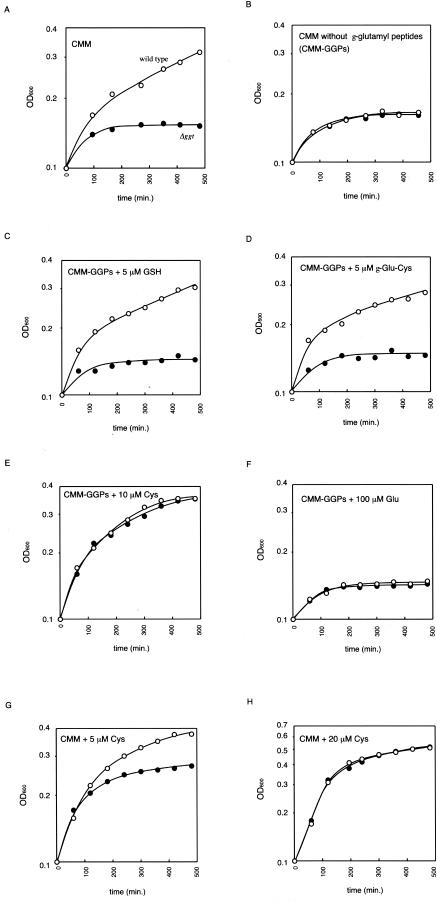

In order to further analyze the mechanism of meningococcal growth in CSF, we tried to monitor meningococcal growth in defined neisserial medium mimicking CSF, which was called CSF-mimicking medium (CMM). The composition was based on that of the defined agar medium for N. meningitidis (4) except that the concentrations of five amino acids (l-glutamine, 500 μM; l-glutamate, 8 μM; l-glycine, 7 μM; l-arginine, 18 μM; and l-cysteine, 1 μM) and three γ-glutamyl peptides (γ-glutamyl-glutamate, 30 μM; γ-glutamyl-cysteine, 2 μM; and GSH, 1 μM) were almost equal to those in human CSF or rat brain (7, 17). Moreover, in this study, 0.5% glucose and 0.1% lactate were added to CMM as carbon sources at concentrations that were 10 times higher than the actual concentrations in human CSF (20) to avoid the effects of carbon starvation. In CMM, H44/76 could grow well but HT1089 could not (Fig. 3A), which was consistent with the results in rat CSF (Fig. 2B). In CMM without the three γ-glutamyl peptides (CMM-GGPs), even H44/76 could not grow (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that the growth of N. meningitidis in CMM was completely dependent on the GGT activity and the presence of γ-glutamyl peptides. The growth defect of H44/76, but not HT1089, was recovered in CMM-GGPs supplemented with 5 μM GSH or 5 μM γ-Glu-Cys (Fig. 3C and D), indicating that the GGT supplied glutamate or cysteine from γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides in CMM to support meningococcal growth. Further experiments revealed that H44/76 and HT1089 grew well in CMM-GGPs supplemented with 10 μM cysteine (Fig. 3E), while the addition of 100 μM glutamate could not suppress their growth failure (Fig. 3F). These results indicated that the meningococcal growth failure in CMM-GGPs was due to the shortage of cysteine and suggested that the meningococcal GGT functioned to supply cysteine from the environmental γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides. Additionally, the growth failure of HT1089 was partially suppressed by supplementation of 5 μM cysteine in CMM (Fig. 3G) and completely suppressed by the addition of 20 μM cysteine (Fig. 3H). The dose-dependent suppression also supported the idea that the growth failure of the Δggt N. meningitidis strain in CMM was due to the shortage of cysteine. Furthermore, it was also confirmed that the growth defect of HT1089 in CSF was considerably ameliorated when cysteine was added to the CSF (data not shown). Taken together, all of the above-mentioned results support the conclusion that meningococcal GGT has a function to accelerate meningococcal multiplication by releasing cysteine from γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides in CMM and CSF.

FIG. 3.

Growth of N. meningitidis strains in defined neisserial media. Meningococcal growth was monitored as optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The open and solid circles correspond to wild-type N. meningitidis strain H44/76 and the derivative Δggt strain HT1089, respectively. Shown are representative data from at least four experiments with similar results. (A) Growth in CMM; (B) growth in CMM-GGPs; (C) growth in CMM-GGPs supplemented with 5 μM GSH; (D) growth in CMM-GGPs supplemented with 5 μM γ-Glu-Cys; (E) growth in CMM-GGPs supplemented with 10 μM cysteine; (F) growth in CMM-GGPs supplemented with 100 μM glutamate; (G) growth in CMM supplemented with 5 μM cysteine; (H) growth in CMM supplemented with 20 μM cysteine.

Previous studies showed that cysteine is required for the growth of N. meningitidis in synthetic media (4, 8), and in the present study, N. meningitidis strain H44/76 showed an auxotrophic phenotype for cysteine in CMM-GGPs (Fig. 3B and E). However, Catlin reported that 90% (52 of 57) of N. meningitidis clinical isolates were not auxotrophic for cysteine on synthetic medium (MCDA) that did not contain cysteine and γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides (5). We also confirmed that H44/76 could grow on MCDA (data not shown), and the genes of enzymes necessary for cysteine synthesis from glycine can be found in the whole-genome sequence of N. meningitidis strain MC58 (24; http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR2/CMRHomePage.spl). The discrepancy may be due to the differences between the concentrations of the amino acids in MCDA and CMM; the concentrations of three amino acids (l-glutamate, l-glycine, and l-arginine) in MCDA are ∼1,000-, 285-, and 28-fold higher than those in CMM (4, 5). It is known that in bacteria the way of utilizing nutrients at micromolar (growth rate-limiting) concentrations is different from that at millimolar concentrations (19) and that natural environments for bacteria are generally nutrient limited (10). Actually, the concentration of cysteine is very limited (<1 μM) in CSF, due to its neurotoxicity (9, 12, 15, 26), compared with that in rat serum (∼64 μM) (12, 28). These facts may imply that N. meningitidis strain H44/76 cannot grow under conditions of limited nutrients, like those in CMM, even if the synthetic pathway for cysteine exists, probably because such a pathway may not work efficiently under these conditions.

The growth failure of H44/76 in CMM-GGPs without γ-glutamyl peptides was suppressed by supplying GSH, γ-Glu-Cys, or Cys (Fig. 3C, D, and E). The Δggt derivative HT1089 could not grow in CMM and CMM-GGPs (Fig. 3A and B), but supplying cysteine restored growth (Fig. 3E, G, and H). As GGT catalyzes the hydrolysis of γ-glutamyl compounds, H44/74 must utilize cysteine hydrolyzed from γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides for its growth in nutrient-limited environments, with the cooperation of other peptidases, as shown in E. coli (22). N. meningitidis multiplies in CSF (Fig. 2B), where the amount of cysteine is very limited but certain amounts of γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides are present (7, 17). We speculate that one of the physiological functions of the ggt gene in N. meningitidis is to supply enough cysteine for growth in CSF.

N. meningitidis strain H44/76 grew well in CMM (Fig. 3A), where the concentration of total free cysteine should be 4 μM if γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides are completely hydrolyzed. Theoretically, the external addition of 4 μM cysteine would suppress the growth failure of HT1089 in CMM, but 20 μM cysteine was required for complete suppression (Fig. 3G and H). The most probable explanation for the discrepancy is that the uptake of cysteine is less efficient than that of γ-glutamyl- cysteinyl peptides.

The growth of the Δggt strain in rat CSF was very slow until 8 h of incubation but seemed to be faster after that time (Fig. 2B), which was different from the results with HT1089 in CMM (Fig. 3A). We do not know the exact reason for the difference. It may be due to the degradation of proteins in the CSF by long-term incubation at 37°C (15) and their utilization by bacteria for growth. Alternatively, it is also possible that N. meningitidis has some other inducible pathways for the promotion of growth under the conditions present in rat CSF.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of the physiological role of meningococcal GGT, which has been used as a laboratory marker for the identification of N. meningitidis. Although it remains unclear whether the growth advantage for meningococcal multiplication in CSF is related to meningococcal pathogenicity in vivo, our observations in this study suggest the possible involvement of N. meningitidis GGT in bacterial virulence.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the ggt allele in H44/76 has been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide database under accession number AB089320.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Labor of Japan. H.T. was also supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grant no. 13770142).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arko, R. J. 1989. Animal models for pathogenic Neisseria species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2:S56-S59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Begley, D. J., A. Reichel, and A. Ermisch. 1994. Simple high-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of free primary amino acid concentrations in rat plasma and cisternal cerebrospinal fluid. J. Chromatogr. B 657:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, J. D., and K. R. Thomas. 1985. Rapid enzyme system for the identification of pathogenic Neisseria spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 21:857-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catlin, B. W., and G. M. Schloer. 1962. A defined agar medium for genetic transformation of Neisseria meningitidis. J. Bacteriol. 83:470-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catlin, B. W. 1973. Nutritional profiles of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Neisseria lactamica in chemically defined media and the use of growth requirements for gonococcal typing. J. Infect. Dis. 128:178-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevalier, C., J. M. Thiberge, R. L. Ferrero, and A. Labigne. 1999. Essential role of Helicobacter pylori γ-glutamyltranspeptidase for the colonization of the gastric mucosa of mice. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1359-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke, D. D., A. L. Lajtha, and H. S. Maker. 1989. Basic neurochemistry, p. 541-564. In G. J. Siegel, B. W. Agranoff, R. W. Albers, and P. B. Molinoff (ed.), Intermediary metabolism, 4th ed. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Frantz, I. D. J. 1942. Growth requirements of the meningococcus. J. Bacteriol. 43:757-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagenfeldt, L., L. Bjerkenstedt, G. Edman, G. Sedvall, and F. A. Wiesel. 1984. Amino acids in plasma and CSF and monoamine metabolites in CSF: interrelationship in healthy subjects. J. Neurochem. 42:833-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harder, W., and L. Dijkhuizen. 1983. Physiological responses to nutrient limitation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 37:1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornhuber, M. E., J. Kornhuber, A. W. Kornhuber, and G. M. Hartmann. 1986. Positive correlation between contamination by blood and amino acid levels in cerebrospinal fluid of the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 69:212-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruse, T., H. Reiber, and V. Neuhoff. 1985. Amino acid transport across the human blood-CSF barrier. An evaluation graph for amino acid concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Neurol. Sci. 70:129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGovern, K. J., T. G. Blanchard, J. A. Gutierrez, S. J. Czinn, S. Krakowka, and P. Youngman. 2001. γ-Glutamyltransferase is a Helicobacter pylori virulence factor but is not essential for colonization. Infect. Immun. 69:4168-4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nassif, X., and M. So. 1995. Interaction of pathogenic neisseriae with nonphagocytic cells. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:376-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry, T. L., S. Hansen, and J. Kennedy. 1975. CSF amino acids and plasma—CSF amino acid ratios in adults. J. Neurochem. 24:587-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polfliet, M. M., P. J. Zwijnenburg, A. M. van Furth, T. van der Poll, E. A. Dopp, C. Renardel de Lavalette, E. M. van Kesteren-Hendrikx, N. van Rooijen, C. D. Dijkstra, and T. K. van den Berg. 2001. Meningeal and perivascular macrophages of the central nervous system play a protective role during bacterial meningitis. J. Immunol. 167:4644-4650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandberg, M., X. Li, S. Folestad, S. G. Weber, and O. Orwar. 1994. Liquid chromatographic determination of acidic β-aspartyl and γ-glutamyl peptides in extracts of rat brain. Anal. Biochem. 217:48-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schryvers, A. B., and I. Stojiljkovic. 1999. Iron acquisition systems in the pathogenic Neisseria. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1117-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schut, F., M. Jansen, T. M. Gomes, J. C. Gottschal, W. Harder, and R. A. Prins. 1995. Substrate uptake and utilization by a marine ultramicrobacterium. Microbiology 141:351-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith, H., E. A. Yates, J. A. Cole, and N. J. Parsons. 2001. Lactate stimulation of gonococcal metabolism in media containing glucose: mechanism, impact on pathogenicity, and wider implications for other pathogens. Infect. Immun. 69:6565-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki, H., W. Hashimoto, and H. Kumagai. 1999. Glutathione metabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Catal. B 6:175-184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki, H., S. Kamatani, E. S. Kim, and H. Kumagai. 2001. Aminopeptidases A, B, and N and dipeptidase D are the four cysteinylglycinases of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 183:1489-1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi, H., and H. Watanabe. 2002. A broad-host-range vector of incompatibility group Q can work as a plasmid vector in Neisseria meningitidis: a new genetical tool. Microbiology 148:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tettelin, H., N. J. Saunders, J. Heidelberg, A. C. Jeffries, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, K. A. Ketchum, D. W. Hood, J. F. Peden, R. J. Dodson, W. C. Nelson, M. L. Gwinn, R. DeBoy, J. D. Peterson, E. K. Hickey, D. H. Haft, S. L. Salzberg, O. White, R. D. Fleischmann, B. A. Dougherty, T. Mason, A. Ciecko, D. S. Parksey, E. Blair, H. Cittone, E. B. Clark, M. D. Cotton, T. R. Utterback, H. Khouri, H. Qin, J. Vamathevan, J. Gill, V. Scarlato, V. Masignani, M. Pizza, G. Grandi, L. Sun, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, E. R. Moxon, R. Rappuoli, and J. C. Venter. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science 287:1809-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Deuren, M., P. Brandtzaeg, and J. W. van der Meer. 2000. Update on meningococcal disease with emphasis on pathogenesis and clinical management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:144-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, X. F., and M. S. Cynader. 2001. Pyruvate released by astrocytes protects neurons from copper-catalyzed cysteine neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 21:3322-3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welborn, P. P., C. T. Uyeda, and N. Ellison-Birang. 1984. Evaluation of Gonochek-II as a rapid identification system for pathogenic Neisseria species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:680-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zunic, G., Z. Jelic-Ivanovic, M. Colic, and S. Spasic. 2002. Optimization of a free separation of 30 free amino acids and peptides by capillary zone electrophoresis with indirect absorbance detection: a potential for quantification in physiological fluids. J. Chromatogr. B 772:19-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]