Abstract

Purpose

Urinary incontinence is one of the most commonly reported and distressing side effects of radical prostatectomy for prostate carcinoma. Several studies have suggested that symptoms may be worse in obese men but to our knowledge no research has addressed the joint effects of obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. We evaluated the association of obesity and lack of physical activity with urinary incontinence in a sample of men who had undergone radical prostatectomy.

Materials and Methods

Height and weight were abstracted from charts, and obesity was defined as body mass index 30 kg/m2 or greater. Men completed a questionnaire before surgery that included self-report of vigorous physical activity. Men who reported 1 hour or more per week of vigorous activities were considered physically active. Men reported their incontinence to the surgeon at their urology visits. Information on incontinence was abstracted from charts at 6 and 58 weeks after surgery.

Results

At 6 weeks after surgery 59% (405) of men were incontinent, defined as any pad use. At 58 weeks after surgery 22% (165) of men were incontinent. At 58 weeks incontinence was more prevalent in men who were obese and physically inactive (59% incontinent). Physical activity may offset some of the negative consequences of being obese because the prevalence of incontinence at 58 weeks was similar in the obese and active (25% incontinent), and nonbese and inactive (24% incontinent) men. The best outcomes were in men who were nonobese and physically active (16% incontinent). Men who were not obese and were active were 26% less likely to be incontinent than men who were obese and inactive (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.52–1.06).

Conclusions

Pre-prostatectomy physical activity and obesity may be important factors in post-prostatectomy continence levels. Interventions aimed at increasing physical activity and decreasing weight in patients with prostate cancer may improve quality of life by offsetting the negative side effects of treatment.

Keywords: obesity, prostatic neoplasms, motor activity, urinary incontinence, prostatectomy

While radical prostatectomy provides a durable effective cure for localized prostate carcinoma,1-3 its use has been tempered by the risk of long-term complications including incontinence.4,5 Urinary incontinence is one of the most commonly reported and distressing side effects of prostate cancer treatment. 6-10 An observational study of quality of life after treatment for prostate cancer demonstrated that sexual and urinary function were the only quality of life domains that had not returned to preoperative levels 2 years after surgery.11 Known causes of postradical prostatectomy incontinence include surgical technique and the underlying characteristics of the urinary system.12,13 Efforts to improve continence have focused on modification of surgical techniques.12,14,15 While these modifications have resulted in improved patient outcomes, they do not guarantee the return of function in all patients. Addressing the underlying physical condition of the patient also offers the hope for return of normal function.

While several observational studies have shown no association of physical activity or obesity with urinary function in prostate cancer survivors,10,16-18 other research has demonstrated that overweight men are more likely to report poor postoperative urinary function. 19-21 To our knowledge no studies have considered the joint effects of obesity and physical inactivity on postoperative outcomes in prostate cancer survivors. Studies in men without diagnosed prostate cancer indicate that lower BMI and higher physical activity levels are associated with reduced rates of urinary incontinence,22-26 but not all studies have found an association.27 In the current study we examine the hypothesis that the combination of obesity and physical inactivity is associated with worse urinary functioning after radical prostatectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between August 2004 and September 2007, 939 patients scheduled to undergo radical prostatectomy at our institution were asked to complete a questionnaire on medical history and lifestyle factors. Of the patients 690 (73%) agreed and 589 (63%) completed the instrument. Subsequently data on urinary incontinence were extracted from charts at the first postoperative visit at approximately 6 weeks (range 3 to 17) and at 58 weeks (range 50 to 74).

If patients reported urinary incontinence at an office visit this was recorded in the chart and patients were coded as such. In some cases the number of pads used was recorded. Thus, to allow for comparisons with previous studies that defined continence based on number of pads used daily, we used a strict definition of incontinence and coded patients who reported using 1 or more pads as incontinent but coded those who did not use pads as continent for an exploratory analysis.10 Height and weight at surgery were extracted from the chart and used to calculate body mass index. WHO cut points were used to classify men as normal weight (BMI less than 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25 to less than 30 kg/m2) and obese (BMI 30 kg/m2 or greater). On the preoperative questionnaire participants were asked about how many hours they spent on vigorous activities such as swimming, brisk walking etc. Response options were none, less than 1 hour per week, 1 hour per week, 2 hours per week, 3 hours per week and 4 plus hours per week. Men who reported exercising 1 or more hours per week were considered active.

We were interested in the joint effects of obesity and physical inactivity, and we classified men as obese and inactive, obese and active, nonobese (overweight or normal) and inactive, or nonobese and active. We examined the bivariable association of our primary exposures and any potential confounders with each outcome using Mantel-Haenszel chisquare tests or t tests as appropriate for the variable structure. Multivariable analyses were adjusted for age and any variable that was significantly associated with the outcome on bivariable analysis. We estimated relative risks of the joint association of physical activity and obesity with incontinence using PROC GENMOD with a log binomial link in SAS® version 9. Other variables assessed and considered confounders were race/ethnicity, marital status, education, smoking, age, nerve bundles preserved in surgery, surgical blood loss, preoperative diabetes, preoperative prostate specific antigen and surgical approach. While we present data collected at the first postoperative visit (6 weeks) our focus is on the data collected 1 year after that (58 weeks) because many patients experience incontinence immediately after surgery which gradually resolves.

RESULTS

Six weeks after surgery incontinence data were available for 407 men. Of these men 405 also had physical activity and obesity data available, and were included in the analysis of the 6-week data. At 58 weeks incontinence data were recorded for 140 of these men. A total of 25 men recorded continence data at 58 weeks but had not recorded it at 6 weeks. These 165 men comprised the 58-week study population. Age at surgery ranged from 39 to 79 years (mean 61). The men tended to be overweight (49%, 210) or obese (32%, 137) at surgery. Of the men 96% were nonHispanic white and 69% underwent laparoscopic surgery. The distribution of sociodemographic factors was similar in men in the 6 and 58-week analyses (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of men who report postoperative urinary functioning

| No. 6-Wk Study Population (%) | No. 58-Wk Study Population (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity: | ||

| Physically active | 257 (63) | 109 (66) |

| Inactive | 148 (37) | 56 (34) |

| BMI: | ||

| Normal | 75 (19) | 19 (12) |

| Overweight | 200 (50) | 92 (55) |

| Obese | 127 (32) | 54 (33) |

| Race: | ||

| White | 386 (95) | 158 (96) |

| African-American | 18 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1) | |

| Surgical approach: | ||

| Laparoscopic | 279 (69) | 123 (75) |

| Retropubic | 121 (30) | 42 (25) |

| Robotic | 4 (1) | |

| Bundles preserved: | ||

| None | 12 (3) | 4 (2) |

| 1 | 7 (2) | 3 (2) |

| 2 | 379 (95) | 153 (96) |

| Education: | ||

| High school or less | 77 (19) | 30 (18) |

| Some college | 108 (27) | 48 (29) |

| College graduate | 216 (54) | 86 (53) |

| Current smoker: | ||

| Yes | 27 (11) | 9 (9) |

| No | 209 (89) | 88 (91) |

| Marital status: | ||

| Married or living as married | 359 (89) | 148 (90) |

| Divorced, separated, widowed, never married | 45 (11) | 17 (10) |

| Diabetes: | ||

| Yes | 34 (8) | 13 (8) |

| No | 369 (92) | 152 (92) |

| Incontinent at 6 wks: | ||

| Yes | 237 (59) | 90 (64) |

| No | 168 (42) | 50 (36) |

Six weeks after surgery 59% of men were incontinent, with the prevalence of incontinence similar between obese (54%) and nonobese men (60%) (p=0.25). Inactive men were slightly more likely to be incontinent (64%) than those who met physical activity recommendations (55%) (p = 0.08). At 58 weeks 22% of men seen were incontinent. Rates of incontinence were higher in obese men (31%) than in nonobese men (18%) (p = 0.05). Rates of incontinence were also higher in inactive men (30%) than active men (18%) at 58 weeks (p = 0.08). Of the men seen at 6 weeks who were not followed at 58 weeks (265) 31% were obese, 62% were physically active and 55% were incontinent.

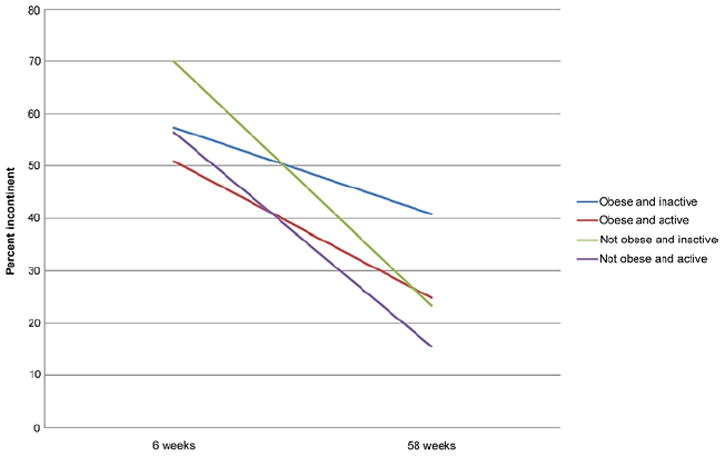

Jointly considering the effects of obesity and physical activity suggests that those who are obese and inactive experience higher rates of incontinence than those who are active and not obese (see figure). At 6 and 58 weeks comparing obese and nonobese men the prevalence of incontinence was higher in those who were inactive. At 58 weeks 16% of nonobese active men and 25% of obese active men were incontinent. Furthermore, it appeared that being active offset the negative consequences of obesity because obese and active men had the same prevalence of incontinence (25%) as nonobese inactive men (24%). The highest prevalence of incontinence was in obese inactive men (41%). However, the joint association of physical activity and obesity with incontinence was not statistically significant at 6 (p = 0.11) or 58 (p = 0.09) weeks.

Figure.

Prevalence of incontinence after prostatectomy by obesity and physical activity.

At 6 weeks incontinence was associated with only surgical approach (p <0.01), blood loss (p = 0.03) and age (p <0.01). At 58 weeks there was no association of incontinence with race/ethnicity (p = 0.65), marital status (p = 0.53), education (p = 0.43), smoking (p = 0.40), age (p = 0.10), bundles preserved (p>0.90), surgical blood loss (p = 0.15), diabetes (p = 0.49) or preoperative prostate specific antigen (p = 0.47). There was an association between incontinence and surgical approach (p = 0.02). Men undergoing laparoscopic surgery were less likely to be incontinent 58 weeks after surgery. Thus, multivariable analyses were only adjusted for age and surgical approach.

In a multivariable model, adjusting for age and surgical approach, nonobese active men were 26% less likely to be incontinent at 58 weeks than obese inactive men, although the difference did not achieve statistical significance (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.52–1.06, table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between obese and inactive men, and either nonobese and inactive (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.53–1.13) or obese and active (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.57–1.26) men. In the multivariable model men undergoing laparoscopic surgery were 20% less likely to be incontinent at 58 weeks vs those undergoing retropubic surgery (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.63–0.99). The exploratory coding of incontinence using pads did not change the continence status of any of the patients at 58 weeks and, thus, was not considered further.

Table 2.

Relative risk of incontinence 58 weeks after prostatectomy

| Crude RR (95% CI) | Multivariable RR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Obese + inactive | 1 | 1 |

| Obese + active | 0.79 (0.53–1.18) | 0.85 (0.57–1.26) |

| Nonobese + inactive | 0.77 (0.52–1.15) | 0.77 (0.53–1.13) |

| Nonobese + active | 0.70 (0.49–1.00) | 0.74 (0.52–1.06) |

Adjusted for age and surgical approach.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that obesity and physical activity are important contributors to post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence. Some previous studies have suggested that obesity contributes to this debilitating complication but relatively little attention has been paid to the effects of physical activity.19-21 Our study is the first to our knowledge to examine the joint effects of these 2 risk factors.

Our results suggest that both factors are important and that increasing physical activity may provide important benefits to prostate cancer survivors independent of weight loss. However, our sample may have been too small to see a significant result. Studies that examine only one of the factors may miss important differences within groups. Physical activity may reduce the risk of incontinence by increasing overall muscle tone, which may facilitate urine control. Obesity may increase the risk of incontinence by placing additional physical strain on the bladder. It may also be that those who are active and not obese are more health conscious and compliant, and thus, more likely to comply with physician recommendations for Kegel exercises. However, the exact mechanisms remain unknown and worthy of additional research. We found the lowest rates of incontinence in men who were physically active and not obese, and the highest rates in men who were obese and inactive. Future studies should consider the role that obesity and physical activity may have in the quality of life of prostate cancer survivors and the potential mechanisms linking them.

In previous research several investigators found no difference in post-prostatectomy incontinence rates by obesity.17,18,28,29 These studies may have enrolled patient populations that were more physically active, and had too few obese and inactive men to show a significant difference. A year after surgery 95% of the patients in the study by Herman et al29 were continent and nearly 90% of the patients in the study by Brown et al28 were continent by 3 months. Both studies defined incontinence as any pad use. Our results were the same regardless of the definition of incontinence used. Freedland et al also found high rates of continence with levels returning to baseline by 24 months, but found a significantly lower rate of continence in obese men than in normal weight men.19 Rates of incontinence in these studies may have been too low to detect differences by body composition. Rates of incontinence were higher in our study. In contrast, Ahlering et al found a significant difference in continence rates between obese and nonobese men with less than half (47%) of obese men continent at 6 months while 91.4% of nonobese men were continent.20 CaPSURE reported that posttreatment urinary function scores at 24 months were highest in normal weight men and lowest in the very obese, but the differences across BMI were not significant.17 Interestingly at 1 year after surgery CaPSURE demonstrated that the highest urinary function scores were in very obese men. None of these studies reported measuring physical activity.

While our findings are novel and raise important points of consideration for future research and clinical care, certain limitations in our data should be noted. As we examined this question in an existing data set, we were not able to collect detailed information on domains and types of physical activity. Future studies that examine this in more detail are warranted. Furthermore, we did not use a validated survey of incontinence, although our measure was similar to existing instruments. It is possible that physicians are more likely to record incontinence than continence in the medical record, thereby inflating the rates of incontinence in our study. However, using a different definition of incontinence did not change our results, which suggests that our findings are robust and not highly sensitive to the definition of incontinence. We also lack data on preoperative continence levels, which may confound our results and should be evaluated in future investigations. In addition, followup data on continence were not available for all of the men in the study, particularly at 58-week followup. At a tertiary care referral center many men follow up initially with their surgeon, but beyond the immediate postoperative period choose to see local physicians for followup care.

Lifestyle modification has the potential to alter the risk of treatment side effects. Unfortunately we did not have information on changes in risk factors including physical activity and obesity, and future studies should examine whether changes in obesity and physical activity are associated with changes in urinary incontinence. In addition, more detailed measures of continence and bother would allow us to examine whether obesity and physical activity are associated with severity of incontinence, and whether that incontinence interferes with activities of daily living.

Given that urinary incontinence is a frequently reported bothersome side effect of prostatectomy, interventions that can prevent or moderate the impact have great clinical care relevance.10 Our findings provide additional support for the importance of monitoring obesity and physical activity in the clinical care of cancer survivors, and suggest that providers should be encouraging patients to be physically active and achieve or maintain a healthy weight after prostatectomy.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge this is the first study to investigate the joint association of physical activity and obesity, and risk of post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence. While our results are intriguing, their interpretation is limited by the small sample size as well as the limited characterization of exposure and outcome. However, our results generate interesting hypotheses and preliminary evidence that justify future studies of the relationship.

Acknowledgments

The St. Louis Men’s Group Against Cancer provided study support, and Alex Klim and Jen Haslag-Minoff assisted with patient recruitment and followup.

Supported by Grant R01CA112028 from the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BMI

body mass index

- CaPSURE™

Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor

References

- 1.Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, et al. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28:555. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hull GW, Rabbani F, Abbas F, et al. Cancer control with radical prostatectomy alone in 1,000 consecutive patients. J Urol. 2002;167:528. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roehl KA, Han M, Ramos CG, et al. Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J Urol. 2004;172:910. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000134888.22332.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talcott JA, Clark JA. Quality of life in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:922. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shamliyan T, Wyman J, Bliss DZ, et al. Prevention of urinary and fecal incontinence in adults. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007;161:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santis WF, Hoffman MA, Dewolf WC. Early catheter removal in 100 consecutive patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2000;85:1067. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber BA, Roberts BL, Chumbler NR, et al. Urinary, sexual, and bowel dysfunction and bother after radical prostatectomy. Urol Nurs. 2007;27:527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeb S, Smith ND, Roehl KA, et al. Intermediateterm potency, continence, and survival outcomes of radical prostatectomy for clinically high-risk or locally advanced prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69:1170. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ukoli FA, Lynch BS, Adams-Campbell LL. Radical prostatectomy and quality of life among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson JW, Donnelly BJ, Coupland K, et al. Quality of life 2 years after salvage cryosurgery for the treatment of local recurrence of prostate cancer after radiotherapy. Urol Oncol. 2006;24:472. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh PC, Marschke PL. Intussusception of the reconstructed bladder neck leads to earlier continence after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2002;59:934. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paparel P, Akin O, Sandhu JS, et al. Recovery of urinary continence after radical prostatectomy: association with urethral length and urethral fibrosis measured by preoperative and postoperative endorectal magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Urol. 2008;55:629. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh PC, Donker PJ. Impotence following radical prostatectomy: insight into etiology and prevention 1982. J Urol. 2002;167:1005. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(02)80325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menon M, Muhletaler F, Campos M, et al. Assessment of early continence after reconstruction of the periprostatic tissues in patients undergoing computer assisted (robotic) prostatectomy: results of a 2 group parallel randomized controlled trial. J Urol. 2008;180:1018. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulholland TL, Huynh PN, Huang RR, et al. Urinary incontinence after radical retropubic prostatectomy is not related to patient body mass index. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2006;9:153. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anast JW, Sadetsky N, Pasta DJ, et al. The impact of obesity on health related quality of life before and after radical prostatectomy (data from CaPSURE) J Urol. 2005;173:1132. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154973.38301.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montgomery JS, Gayed BA, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Obesity adversely affects health related quality of life before and after radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2006;176:257. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedland SJ, Haffner MC, Landis PK, et al. Obesity does not adversely affect health-related quality-of-life outcomes after anatomic retropubic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2005;65:1131. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahlering TE, Eichel L, Edwards R, et al. Impact of obesity on clinical outcomes in robotic prostatectomy. Urology. 2005;65:740. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Roermund JG, van Basten JP, Kiemeney LA, et al. Impact of obesity on surgical outcomes following open radical prostatectomy. Urol Int. 2009;82:256. doi: 10.1159/000209353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kikuchi A, Niu K, Ikeda Y, et al. Association between physical activity and urinary incontinence in a community-based elderly population aged 70 years and over. Eur Urol. 2007;52:868. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smoger SH, Felice TL, Kloecker GH. Urinary incontinence among male veterans receiving care in primary care clinics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:547. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muscatello DJ, Rissel C, Szonyi G. Urinary symptoms and incontinence in an urban community: prevalence and associated factors in older men and women. Intern Med J. 2001;31:151. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2001.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidbauer J, Temml C, Schatzl G, et al. Risk factors for urinary incontinence in both sexes Analysis of a health screening project. Eur Urol. 2001;39:565. doi: 10.1159/000052504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Oyen H, Van Oyen P. Urinary incontinence in Belgium; prevalence, correlates and psychosocial consequences. Acta Clin Belg. 2002;57:207. doi: 10.1179/acb.2002.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson RL, Furner SE. Risk factors for the development of fecal and urinary incontinence in Wisconsin nursing home residents. Maturitas. 2005;52:26. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown JA, Rodin DM, Lee B, et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy and body mass index: an assessment of 151 sequential cases. J Urol. 2005;173:442. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000148865.89309.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman MP, Raman JD, Dong S, et al. Increasing body mass index negatively impacts outcomes following robotic radical prostatectomy. JSLS. 2007;11:438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]