Abstract

Patients with hemophilia A present with spontaneous and sometimes life-threatening bleeding episodes that are treated using blood coagulation factor VIII (fVIII) replacement products. Although effective, these products have limited availability worldwide due to supply limitations and product costs, which stem largely from manufacturing complexity. Current mammalian cell culture manufacturing systems yield around 100 µg/l of recombinant fVIII, with a per cell production rate of 0.05 pg/cell/day, representing 10,000-fold lesser production than is achieved for other similar-sized recombinant proteins (e.g. monoclonal antibodies). Expression of human fVIII is rate limited by inefficient transport through the cellular secretory pathway. Recently, we discovered that the orthologous porcine fVIII possesses two distinct sequence elements that enhance secretory transport efficiency. Herein, we describe the development of a bioengineered fVIII product using a novel lentiviral-driven recombinant protein manufacturing platform. The combined implementation of these technologies yielded production cell lines that biosynthesize in excess of 2.5 mg/l of recombinant fVIII at the rate of 9 pg/cell/day, which is the highest level of recombinant fVIII production reported to date, thereby validating the utility of both technologies.

Introduction

The congenital bleeding disorder hemophilia A results from genetic alterations that create a deficiency of the circulating blood coagulation factor VIII (fVIII). FVIII is a procofactor that, upon activation by thrombin, functions as a cofactor for the serine protease factor IXa within the intrinsic tenase complex of the blood coagulation cascade. Deficiencies of either fVIII or factor IX result in the clinically indistinguishable bleeding disorders, hemophilia A or B, respectively. The development of recombinant fVIII and factor IX products has revolutionized the treatment of hemophilia and transformed previously untreatable, lethal disorders into treatable, nonlethal disorders with residual morbidity due to suboptimal treatment frequency. Despite drastic improvement in the care of patients with hemophilia A, problems remain. Most prominently, fVIII products only are available to one-third of the global hemophilia A population due to exorbitant product cost. The high cost of fVIII products stems largely from inefficiencies in commercial manufacturing, which have contributed to product shortages even in economically privileged countries.1

Recombinant fVIII products are produced exclusively using cultured mammalian cells, e.g. baby hamster kidney or Chinese hamster ovary cells, in large-scale fermenting bioreactors. Several techniques are used to maximize the production of recombinant fVIII including (i) amplification of the fVIII transgene using dihydrofolate reductase/methotrexate selection, (ii) addition of fVIII stabilizing agents to the culture medium [e.g. bovine/human albumin or co-expression of von Willebrand factor (vWf)], and (iii) maximizing cell growth/density by continuous-perfusion fermentation. Apart from general advances in cell culture technology, progress has been made toward deciphering the bottlenecks in fVIII biosynthesis, which primarily occur in the endoplasmic reticulum.2 Multiple strategies have been implemented with varying success to increase the biosynthetic efficiency of human fVIII.3,4

The current studies were focused on improving product manufacturing capability through bioengineering of the fVIII molecule itself and utilizing a novel lentiviral gene transfer and protein production platform. The most efficient fVIII expression constructs reported to date include the high-expression sequence elements derived from porcine fVIII.5,6,7 Recombinant porcine fVIII is expressed at 10- to 100-fold greater levels than recombinant human fVIII.8 Although there is a correlation between fVIII production and steady-state fVIII mRNA levels, porcine fVIII is observed to be expressed at higher levels than human fVIII on a per mRNA basis consistent with a translational or post-translational regulatory differential. In a subsequent study, it was demonstrated that hybrid human/porcine (HP) fVIII molecules minimally containing porcine-specific sequences within the A1 and ap-A3 domains retain the interspecies expression differential.7 Furthermore, using metabolic labeling experiments, it was shown that the expression differential results primarily from improved secretion rate.

Another advance in recombinant protein expression, described herein, is the use of lentiviral vectors to deliver the transgene of interest and drive expression in manufacturing cell lines. In contrast to plasmid transfection technologies, lentiviral vector delivery facilitates high transgene copy number with individually distinct integration sites. The current studies were designed around the development and characterization of an optimized and improved recombinant fVIII manufacturing platform incorporating both a high-expression fVIII transgene (i.e. a hybrid HP-fVIII construct) and lentiviral transgene delivery/expression that could be used to improve globally the treatment of patients with hemophilia A.

Results

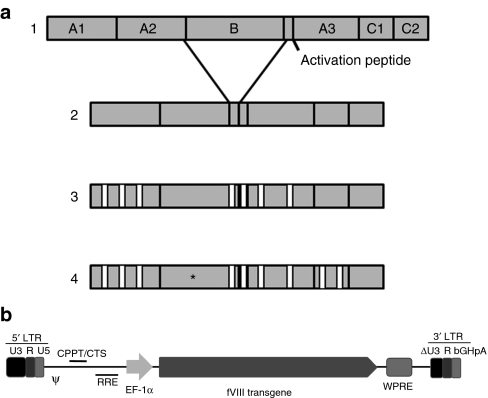

Design and construction of ET-801i

FVIII contains a domain structure, A1-A2-B-ap-A3-C1-C2, defined by internal sequence homologies (Figure 1a). The B domain is not necessary for procoagulant function and its deletion reduces the size of the fVIII transgene and protein by 39%. Therefore, B-domain removal was the first consideration accepted for bioengineering. Next, porcine sequences present in the A1 and ap-A3 domains that previously were defined as necessary and sufficient for high-level expression were included.7 Lastly, for immunogenicity considerations, three alanine substitutions in the A2 domain and porcine sequences in the C1 domain were added. These sequences have been demonstrated to either reduce the immunogenicity of human fVIII or display a reduction in epitope recognition in the murine hemophilia A model.9,10 The ultimate fVIII construct, designated ET-801i, is 88% identical to B-domain-deleted (BDD) human fVIII at the amino acid level. The ET-801i transgene was cloned into a recombinant human immunodeficiency virus-1-based lentiviral vector production system (depicted in Figure 1b), which was used to generate vesicular stomatitis virus-G pseudotyped viral particles.

Figure 1.

Design of ET-801i and the lentiviral production platform. (a) Design of ET-801i. The percent amino acid identities to B-domain-deleted recombinant human fVIII (h-fVIII) are 100, 90, and 88, respectively for constructs 2, 3, and 4. FVIII domain boundaries were defined using the human fVIII amino acid sequence numbering21 as follows: residues 1–372 (A1), 373–740 (A2), 1,649–1,689 (ap), 1,690–2,019 (A3), 2,020–2,172 (C1), and 2,173–2,332 (C2). (b) Schematic representation of the ET-801i transgene in the LentiMax expression vector. ET-801i was cloned into the LentiMax expression vector and recombinant lentivirus vector encoding the ET-801i transgene under the control of the elongation factor 1-α (EF-1α) promoter was generated using the LentiMax production system. cPPT, central polypurine tract; CTS, central termination sequence; LTR, long-terminal repeat; RRE, Rev-responsive element; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis post-transcriptional regulatory element.

Generation and characterization of ET-801i production cell lines

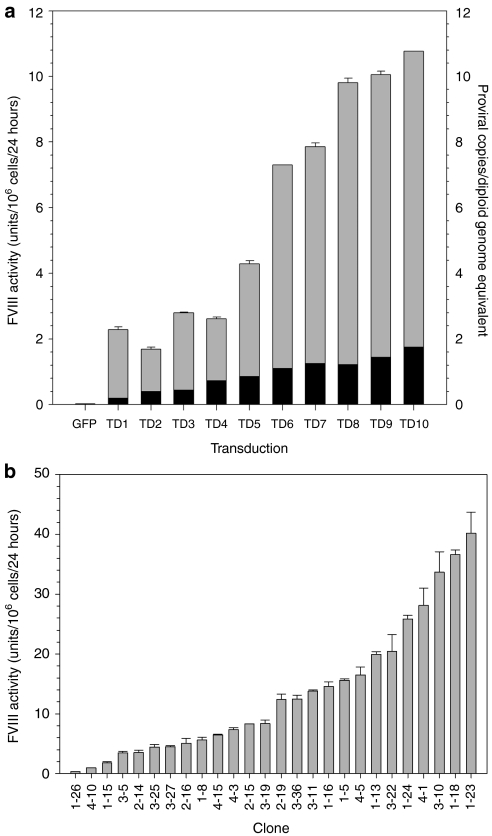

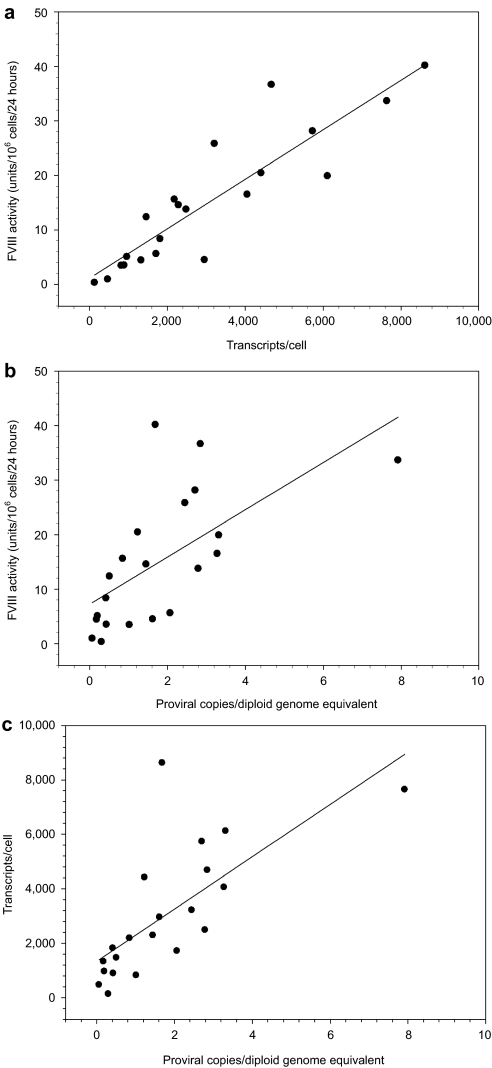

Baby hamster kidney–derived cells were transduced serially with ET-801i encoding lentiviral vector. Following each transduction, the cell population was analyzed for fVIII production and proviral copy number (Figure 2a). Overall, fVIII production rate and proviral copy number were observed to increase with additional transduction events. From the population of cells that underwent 10 rounds of transduction, clonal isolates were obtained by limiting dilution. Individual clones were analyzed for fVIII production rate. Twenty-six clones, selected for further analysis based on high-level fVIII expression, displayed expression rates varying from 0.3 to 40 units/106 cells/24 hours and displayed a mean of 14 units/106 cells/24 hours (Figure 2b). Clonal lines were examined further for steady-state fVIII mRNA levels and proviral copy number (Figure 3a,b). Mean mRNA and proviral copy numbers were 2,840 and 1.6/cell, respectively. Furthermore, there was a strong correlation (r = 0.89, P < 0.0001) between fVIII expression and fVIII mRNA. The correlation observed between fVIII activity and proviral copy number data was not as strong (r = 0.64), but still significant (P = 0.002). Additionally, there was a significant correlation (P = 0.0003) between mRNA transcript levels and proviral copy number with, on average, 1,780 steady-state mRNA transcripts expressed per integrated transgene (Figure 3c). Similar results were obtained with a second independently generated set of 53 clones supporting the reproducibility of cell line development using lentiviral vector gene transfer and expression (Supplementary Figure S1). One of the high-producing clones from the former set, clone 3–10, was selected for further analysis and scale-up production of ET-801i. Southern and northern blot analysis of clone 3–10 indicated the presence of five copies of the ET-801i transgene and expression of a single mRNA transcript species of the expected size (Supplementary Figure S2). Additionally, subclonal analysis of fVIII expression from clone 3–10 isolates demonstrated consistent, high-level expression from all subclones, supporting the claim of clonality (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 2.

ET-801i production following lentiviral transduction. (a) Serial transduction of baby hamster kidney–derived (BHK-M) cells using ET-801i lentivirus was performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 for transductions 1–3, MOI of 10 for transduction 4, and MOI of 20 thereafter. After each transduction, fVIII production was assessed using a one-stage coagulation assay (gray bars) and proviral copy number determined by quantitative PCR (black bars). Lenti-GFP, a LentiMax lentiviral vector expressing the green fluorescent reporter protein under the control of the elongation factor-1α (EF-1α) promoter, was used as a negative control. (b) ET-801i expression from individual BHK-M clones was studied by limiting dilution of the mixed cell population post-transduction and determination of fVIII production by one-stage coagulation assay. Error bars represent one sample standard deviation. GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Figure 3.

Clonal analysis of BHK-M cells expressing ET-801i. A total of 26 clones were analyzed for transgene copy number and transcript levels. (a) FVIII activity versus mRNA transcript level, (b) fVIII activity versus transgene copy number, and (c) transgene copy number versus RNA transcript levels are plotted.

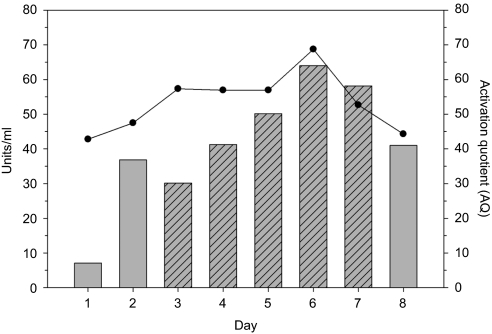

Pilot-scale manufacturing of ET-801i

ET-801i production from clone 3–10 was scaled up for pilot protein production and biochemical characterization. Cells were cultured at an approximate density of 105 cells/cm2 in four, 500 cm2 flasks containing 125 ml serum-free medium each. Conditioned medium was monitored daily for fVIII activity and activation quotient (Figure 4). FVIII production peaked on day 6 at a production rate of 160 units/106 cells/24 hours or 9 pg/cell/day. In total, 130,000 units, equating to ~7.3 mg, of ET-801i were harvested in a total media volume of 2.5 l obtained from collection days 3–7.

Figure 4.

Pilot-scale ET-801i production run. Clone 3–10 cells were cultured in 500 cm2 flasks under serum-free conditions for 8 days. Media was collected daily (hatched bars) and fVIII activity in the bulk supernatant was measured. Gray bars represent fVIII activity as determined by one-stage coagulation assay and black circles represent the activation quotient as determined by a two-stage coagulation assay.

Purification and biochemical characterization of ET-801i

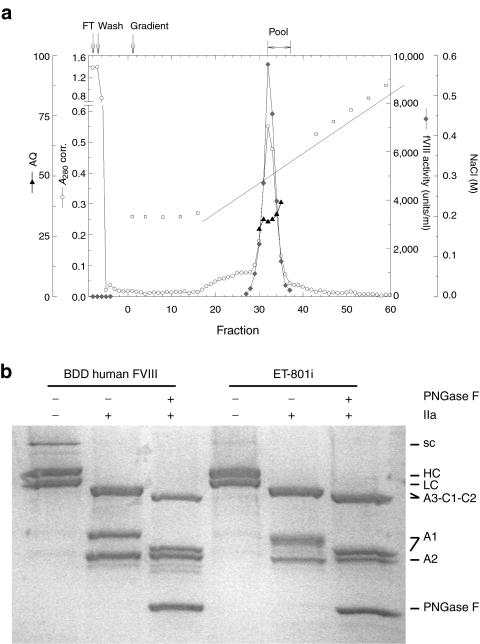

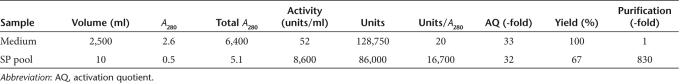

Due to the high concentration of ET-801i in the starting material, it was possible, for the first time, to obtain highly purified material using a single cation-exchange chromatography procedure (Figure 5a and Table 1). Approximately 4.9 mg of highly purified ET-801i was isolated with 830-fold purification. The final material was calculated to have a specific activity of 3,000 units/nmol or 17,700 units/mg using a molar extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 254,955/mol/l/cm based on the predicted tyrosine, tryptophan, and cysteine content.11 The purity of ET-801i was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and compared to recombinant BDD human fVIII (Figure 5b). A small amount of single chain material, which was sensitive to cleavage by thrombin, was present. No major contaminants were observed.

Figure 5.

Analysis of purified ET-801i. (a) FVIII-containing cell culture supernatant was loaded onto an SP-Sepharose Fast Flow column and ET-801i was eluted using a linear 0.18–0.7 mol/l NaCl gradient. Fractions collected were assayed for A280, fVIII activity, AQ, and conductivity. (b) Two µg of human fVIII and ET-801i were subjected to 4–15% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions and visualized by silver staining. Where indicated, samples were treated with 100 nmol/l porcine thrombin ± PNGase F endoglycosidase for 5 minutes before analysis to demonstrate proteolytic activation and the presence of N-linked glycan modifications, respectively. BDD, B-domain-deleted; HC, heavy chain; LC, light chain; SC, single chain.

Table 1. ET-801i purification.

Purified ET-801i was assessed for glycosylation, interaction with vWf, and activity decay following activation by thrombin. Treatment of ET-801i with thrombin and endoglycosidase PNGase F resulted in a change in relative mobility for the A1 and A3-C1-C2 (light chain) protein fragments (Figure 5b). No change in relative mobility of the A2 domain was observed following PNGase F treatment. These data suggest a glycosylation pattern for ET-801i that is consistent with what has been described previously for recombinant BDD human and BDD porcine fVIII.12 The interaction of fVIII with vWf is important because the circulatory lifetime of fVIII, and consequently, hemostatic efficacy is governed by its interaction with vWf. To confirm that ET-801i retains the ability to bind vWf, an in vitro binding experiment was performed using purified human fVIII, ET-801i, and human vWf (Supplementary Figure S4). ET-801i was observed to bind human vWf equivalently to BDD human fVIII. These data support the prediction that ET-801i would display normal pharmacokinetics in patients with hemophilia A. Lastly, the decay of ET-801i following proteolytic activation by thrombin was studied. As shown in Supplementary Figure S5, activated ET-801i demonstrated a decay rate that was approximately twofold slower than activated human fVIII.

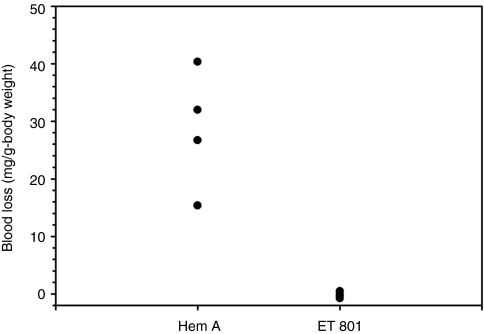

In vivo efficacy of ET-801i

To confirm the in vivo functionality of ET-801i, hemophilia A mice were infused with either saline or ET-801i at a dose of 290 units/kg, which was empirically determined to restore circulating fVIII activity to near normal murine levels.12 Following administration of saline or ET-801i, the mice were subjected to a hemostatic challenge using tail transection and total blood loss was determined over a 40-minute period. Hemophilia A mice injected with saline alone had a mean blood volume loss of 29.6 mg/g body weight. In contrast, mice infused with ET-801i displayed mean blood loss of 0.1 mg/g body weight, which was significantly less than controls (P = 0.029; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

In vivo efficacy of ET-801i. Hemophilia A mice were infused with either saline, or ET-801i at a dose of 290 units/kg. Following administration of saline or fVIII, the mice were subjected to a hemostatic challenge of 4 mm tail transection. Total blood loss was determined over a 40-minute period.

Discussion

The hemophilias (A and B) are rare bleeding disorders toward which much scientific and medical effort has been devoted. In 1840, blood transfusion was used for the first time to stop postoperative bleeding in a hemophilia patient. In 1968, the first commercial human plasma–derived coagulation factor concentrate became available. Cloning of the fVIII gene in 1984 facilitated the development of recombinant fVIII protein products that became commercially available in 1992. This was viewed as a dramatic therapeutic improvement due to the perceived safety advantage the recombinant products have over plasma-derived products, which proved responsible for the infection of thousands of hemophilia patients with human immunodeficiency virus and/or hepatitis C virus during the 1980s. Since the development of recombinant fVIII, progress in the treatment of hemophilia A has slowed. The current limitations to treatment are (i) access to fVIII-replacement products, (ii) the cost of fVIII-replacement products, (iii) the development of anti-fVIII immune responses that block treatment efficacy, and (iv) morbidity due to joint disease.

With an incidence of 1 in 5,000 newborn males, it is estimated that ~10,000 children born every year worldwide are afflicted with hemophilia A. Of these individuals, <3,000 will receive any form of treatment. Without treatment, hemophilia A is a lethal disorder resulting in death before adulthood. However, fVIII-replacement therapy can extend the lifespan of affected individuals to that similar to the general population. Worldwide treatment of hemophilia A is limited due to the cost of fVIII products, which currently exceeds $100,000 per year per patient. High manufacturing cost, resulting primarily from the low-level biosynthesis of human fVIII, is considered the significant factor in the pricing of recombinant fVIII products.1 Due to the extensive post-translational modifications required for fVIII function (e.g. N/O-linked glycosylation, tyrosine sulfation, and PACE/furin processing), clinical-grade fVIII products cannot be produced using more cost-effective bacterial, yeast, or insect cell-based expression systems. Even with state-of-the-art commercial production facilities and technology, recombinant human fVIII is expressed at 100- to 1,000-fold lower levels than other plasma proteins from mammalian cell expression systems.2 Unless the worldwide fVIII supply increases and prices drop significantly, hemophilia A will remain an important health burden to human society. One strategy for improving hemophilia A care is to develop improved recombinant protein products, e.g. manufactured more efficiently or have increased hemostatic efficacy. Herein, we describe the development of a novel bioengineered, recombinant fVIII product, ET-801i, using an optimized lentiviral expression platform.

Recombinant human fVIII products are biosynthesized by mammalian cells in large fermenting bioreactors. Secreted fVIII is purified from conditioned culture medium using a series of filtration, immunoaffinity, size-exclusion, and ion-exchange chromatography steps. Viral inactivation procedures are incorporated into the purification protocol for added safety. Once purified, the bulk fVIII material is formulated with stabilizing agents and freeze-dried before packaging. A description of the standard manufacturing processes employed in the commercial production of recombinant fVIII has been reviewed previously.13 First generation recombinant fVIII products were stabilized using human serum albumin that theoretically could harbor viral contaminants. Therefore, there has been a significant push to develop second and third generation fVIII products that are considered “animal-product free” and instead are stabilized with sucrose and other additives. Due to the perceived improved safety profile of newer generation recombinant products over both plasma-derived and first generation products, many previously treated and the majority of previously untreated patients have transitioned to second and third generation fVIII products. This demand has created multiple fVIII product shortages and lead to the implementation of strategies to temporarily ration fVIII supplies.1 Publications have stated that the standard level of recombinant human fVIII production is <1 unit/106 cells/day.2 Typically, the final recombinant human fVIII product has a specific activity between 4,000 and 10,000 units/mg protein and the cost of a single treatment for a 70 kg adult is $2,500–5,000. A product that can be manufactured more efficiently, e.g. ET-801i, has the potential to dramatically reduce the cost of goods for recombinant fVIII products. Presumably, manufacturing of ET-801i would follow a similar process to that described above for current recombinant fVIII products. However, the expected yield per manufacturing run would be expected to be 16- to 160-fold greater based on the data presented herein. This magnitude of production cost differential could translate into a 50–70% reduction in the final cost of goods of ET-801i compared to other recombinant fVIII products.

Immunogenicity is a concern for novel biopharmaceuticals, and is especially so for fVIII products, since historically, 20–30% of severe hemophilia A patients develop inhibitory antibodies that prevent efficacy of fVIII-replacement therapy. However, this issue is difficult to address as there is not a reliable predictive immunogenicity model system apart from clinical trials in humans. Despite this shortcoming, the hemophilia A mouse model has been shown to display many of the hallmark features described for the immune response to fVIII in human hemophilia A patients. Therefore, immunogenicity testing of ET-801i using hemophilia A mice is warranted as part of a preclinical development program. Lollar and colleagues have devoted considerable effort to the comparison of immunogenicity between human and porcine recombinant fVIII.10 In this studies, it was determined that the overall immune response to the two fVIII proteins is similar, but that there are subtle differences in the epitopes recognized on each protein. We have used these data to rationally design ET-801i to minimize porcine-specific epitopes (e.g. substitution of the human C1 domain with the less immunogenic orthologous porcine sequences), while maximizing the high-expression property.

Two independent technologies were utilized to maximize ET-801i expression: (i) high-expression elements derived from porcine fVIII and (ii) lentiviral gene transfer. We previously described the identification and characterization of high-expression porcine fVIII elements located in the A1 and A3 domains through the generation and testing of hybrid HP-fVIII constructs.7 In its final humanized form, ET-801i retains 12% porcine sequence. These elements function to increase secretory efficiency likely through more favorable post-translational folding kinetics and/or thermal stability in its functional form. These properties theoretically would act to decrease involvement of the ER quality control pathway, which has been shown to rate-limit the biosynthesis of human fVIII (for review, see ref. 2).

Several advantageous properties were bioengineered into ET-801i including high-expression elements, reduced immunogenicity sequences, and slow decay of thrombin-activated fVIII. Dissociation of the A2 subunit from the heterotrimeric fVIIIa molecule results in loss of fVIIIa cofactor activity.14,15,16 Conceivably, the hemostatic efficacy of fVIII increases as the rate of fVIII A2 subunit dissociation decreases. Consistent with this, it has been demonstrated that fVIIIa A2 subunit dissociation is important to fVIII function in vivo. Pipe et al. have identified mild hemophilia A patients with missense mutations at Ala284 and Ser289 in the A1 domain and at Arg531 in the A2 domain who have abnormally fast A2 subunit dissociation.17,18 Because these patients have a bleeding phenotype, the rate of A2 subunit dissociation apparently is important during normal hemostasis. Previously, we have shown that following thrombin activation, the decay of porcine fVIIIa is substantially slower than human fVIIIa.6,16 Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that the major determinant of slow fVIIIa decay is amino acid sequence in the A1 domain that differs between human and porcine fVIII.19 Therefore, the slow decay of thrombin-activated ET-801i may translate to increased efficacy at lower dose, which could reduce further the economic burden to patients with hemophilia A.

The second novel technology implemented in this study was the use of lentiviral vectors to deliver the fVIII transgene to a production cell line and drive transgene expression through nonviral regulatory elements. Lentiviral gene delivery facilitates the generation of protein-producing mammalian cell lines quickly, in as little as 4 weeks. The lentiviral system is inherently flexible and modular allowing for insertion of nucleic acid sequences under 6 kilobases in length. Transduction of cells with lentiviral particles is straightforward and cell lines theoretically should be able to produce protein indefinitely due to stable integration of the proviral genome into the host cell genome. High protein production levels result primarily from two aspects of lentiviral delivery. First is the ability to achieve high transgene copy number through multiple rounds of serial transduction. Second is the genome context into which lentiviral vectors predominantly integrate. Recent work stemming from the use of lentiviral vectors in clinical gene therapy applications has shown that lentiviral vectors display a distinct preference for integration within gene coding elements, without skewing toward transcriptional start sites. These properties improve upon two aspects of plasmid gene transfer that are suboptimal, random, and single-site integration.

In a parallel study, it was demonstrated that lentiviral vectors could generate high producer clones expressing recombinant erythropoietin at the 10–20 g/l level (B. Dropulic, unpublished results). For both studies, features of the lentiviral vector system were engineered to increase potential safety and efficacy. For example, the transcriptional units that comprise the viral structural elements were constructed so that there is no possibility for read-though transcription between the gag-pol structural and vesicular stomatitis virus-G envelope proteins, therefore mitigating the risk of the generation of any adverse recombinant virus. The ET-801i-encoding vectors produced were replication incompetent and did not encode for any proteins other than ET-801i. The vectors themselves have a short half-life (~6–12 hours) and rapidly are degraded upon entry into the cells. Furthermore, residual viral material is diluted out of the original cell exponentially through cell division. Therefore, it is not anticipated that any lentiviral-derived material (i.e. viral load) is present in the production cell lines except for the proviral DNA sequence, which is integrated into the host cell chromosomes. However, as part of preclinical biosafety testing, measurement of the levels of residual lentiviral protein and RNA should be performed to verify these theoretical predictions.

Previously published expression rates for human fVIII are between 1 and 10 units/106 cells/24 hours.2,5,7,8,20 Recently, we directly compared the expression of a B-domain-deleted human fVIII variant to a similar hybrid HP-fVIII variant, which is identical to ET-801i except for the A2 and C1 domain sequences that were added to the latter for immunogenicity purposes.5 In the previous study, it was demonstrated that HP-fVIII expression was significantly (10- and 100-fold for the mean and peak, respectively) higher than B-domain-deleted human fVIII expression from a similar lentivector-based expression system. As the level of expression achieved was approximately three- to fivefold higher than we have achieved previously for high-expression, HP-fVIII constructs using standard plasmid transfection technology,5,7,8,20 it can be concluded that there is an additive effect of the high-expression porcine fVIII elements and the lentiviral delivery/expression system. This represents a significant advancement in recombinant fVIII technology that could transform the production of future clinical hemophilia A therapeutics and facilitate treatment of a larger proportion of the patients worldwide with hemophilia A, which is the single greatest treatment limitation.

Materials and Methods

Materials. Advanced Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F-12 medium, AIM-V medium, certified, heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin–streptomycin solution, GlutaMax, and Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Human fVIII-deficient plasma and normal pooled human plasma (FACT) were purchased from George King Biomedical (Overland Park, KS). Surfact-Amps 80 (Tween-80) was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). Automated activated partial thromboplastin (TriniCLOT) reagent was purchased from Trinity Biotech (Wicklow, Ireland). Porcine thrombin was a gift from Pete Lollar, Emory University. Endoglycosidase PNGase F was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Clotting times were measured using an ST art Coagulation Instrument (Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres, France). Genomic DNA and total RNA from cultured cells was isolated using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit and RNeasy Mini Kit, respectively, from QIAGEN (Germantown, MD). In vitro transcribed fVIII RNA standards were generated using the mMessage mMachine Kit by Ambion (Austin, TX). FVIII RNA quantitation was performed using SYBR GREEN PCR Master Mix, TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents, and ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). SP-Sepharose, Source Q, mono S, and mono Q chromatography resins were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). A breeding colony of hemophilic A mice was established from exon 16-disrupted hemophilia A mice backcrossed to a C57BL/6 genetic background originally obtained from Leon Hoyer (Holland Laboratories, American Red Cross).

Methods.

Lentiviral production: Human immunodeficiency virus–based lentiviral vectors (LentiMax system) containing the ET-801i transgene were manufactured by Lentigen (Gaithersburg, MD). Briefly, the ET-801i transgene was subcloned into a lentiviral vector where transgene expression was driven by the human elongation factor-1α promoter and contained the woodchuck hepatitis post-transcriptional regulatory element. Research grade lentiviral vector particles were manufactured by transient transfection using helper constructs. Harvests were concentrated and titers were obtained by performing quantitative PCR of the gag region of the lentiviral vector on extracted genomic DNA from transduced HEK 293 cells. Production lots of ET-801i-encoding lentiviral vector were released with titers exceeding 108 transducing units/ml.

Cell culture, transduction, and clonal isolation: Baby hamster kidney-M cells were maintained in Advanced DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (100 units/ml each), and 2 mmol/l GlutaMax at 37 °C with 5% CO2, herein described as complete DMEM/F12. Repeated transductions at various multiplicity of infection were performed by incubating ~100,000 cells/well plated onto collagen-1-coated 24-well plates (BIOCOAT; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with lentivector in a final volume of 500 µl of complete DMEM/F12 supplemented with 8 µg/ml of polybrene (Specialty Media). At 24 hours post-transduction, virus-containing media was replaced with fresh complete Advanced DMEM/F12 and transduced cells were allowed to recover by culturing overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Transduced cells were then replated for another round of transduction as outlined above and transductions were repeated until fVIII expression did not increase significantly above that of cell from the previous transduction. Following each transduction, cells were analyzed for fVIII activity, integration events, and transcript expression as described below. Clonal isolation was performed by single-cell cloning by limiting dilution into 96-well plate and visual examination of wells for single cell. After 2 weeks in culture, single-cell clones were expanded sequentially from 96-well plate to 48-well, 24-well, 12-well, 6-well, and 100-mm dishes for further testing. Each clone was analyzed for fVIII activity, integration events, and transcript expression as described below.

Measurement of fVIII activity and activation quotient: FVIII activity was measured using the activated partial thromboplastin reagent-based one-stage coagulation assay in an ST art Coagulation Instrument (Diagnostica Stago) using human fVIII-deficient plasma as a substrate as previously described.12 Briefly, for characterization of transduced cells, 2.5 × 105 cells/well were plated in triplicate onto 6-well plates and allowed to expand overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Conditioned medium then was replaced with AIM-V serum-free medium and cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 hours before assaying fVIII activity. All coagulation assays were performed in duplicate from two independent wells and activity (units/ml) was determined by linear regression analysis of clotting times against a FACT standard curve. During production, fVIII activity was measured by one-stage coagulation assay daily from samples of conditioned AIM-V medium. Determination of the activation quotient was performed using a two-stage coagulation assay as previously described.12 The activation quotient is defined as the ratio of fVIII activity measured by two-stage coagulation assay divided by the fVIII activity measured by one-stage coagulation assay. The activation quotient serves as a product quality metric for purified recombinant fVIII with an acceptable value being >24 and typically <80.

Measurement of fVIII transgene copy number: Total genomic DNA from transduced cells was isolated using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit following the manufacture's protocol for cells. Genomic DNA was quantitated. Transgene copy number was determined by real-time quantitative PCR of genomic DNA isolated from transduced cells using the following A1 porcine-specific fVIII-specific primers: forward primer, 5′-CAG GAG CTC TTC CGT TGG-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-CTG GGC CTG GCA ACG C-3′. Transgene copy numbers were determined in a background of 1 µg genomic DNA and absolute quantitation determined against a standard curve generated using genomic DNA from a cell line harboring 3 copies/cell of fVIII transgene (as described below). Briefly, PCR reactions for unknown samples were carried out in 25 µl of total volume containing 1× SYBR Green PCR master mix, 250 µmol/l forward and reverse primers, 50 ng of unknown sample genomic DNA, and 950 ng of control HEK-293T genomic DNA. PCR reactions to generate the standard curve were also in 25 µl of total volume containing 1× SYBR Green PCR master mix, 250 µmol/l forward and reverse primers, standard genomic DNA ranging from 500,000 to 64 copies generated by serial dilution in a total of 1 µg HEK-293T genomic DNA. A standard curve was derived using genomic DNA obtained from a HeLa clonal cell line harboring 3 copies/cell of an fVIII transgene, which was generated by lentiviral transduction of HeLa cells followed by cloning by limiting dilution. Southern blot analysis is used routinely to confirm the presence of 3 copies/cell of fVIII transgene in standard genomic DNA sample. Quantitative PCR was performed using the following conditions: one cycle at 95 °C for 10 minutes followed by 40 amplification cycles of 90 °C for 15 seconds then 60 °C for 1 minute. Postreaction dissociation analysis was performed to confirm single-product amplification. The copies per cell calculation was made using a value of 8,333 copies per 50 ng of genomic DNA.

Measurement of fVIII transcript expression: Total RNA was extracted from cell lines using RNeasy Mini Kit following manufacturer's instructions and using QIAshredder homogenizers. RNA concentrations were determined by absorbance at 260 nm in 10 mmol/l Tris–HCl pH 7.0. Porcine fVIII RNA standard, used for absolute quantitation of fVIII transcripts by reverse transcription RT-PCR, was generated as described previously.6 PCR reactions were carried out in 25 µl of total volume containing 1× SYBR Green PCR master mix, 300 µmol/l forward and reverse primers, 12.5 units of MultiScribe, 10 units of RNase Inhibitor, and 5 ng of sample RNA. Serial dilutions from 106 to 102 transcripts/reaction were utilized for generation of the standard curve, which also included 5 ng of yeast transfer RNA to mimic the environment of sample RNAs. The oligonucleotide primers used were located in the fVIII sequence encoding the A2 domain at positions 2,047–2,067 for forward primer (5′-ATGCACAGCATCAATGGCTAT-3′) and 2,194–2,213 for reverse primer (5′-GTGAGTGTGTCTTCATAGAC-3′) of the human fVIII complementary DNA sequence. These primers recognize both human and porcine fVIII sequences, which are identical at these positions. One-step quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed by incubation at 48 °C for 30 minutes for reverse transcription followed by one cycle at 95 °C for 10 minutes, and 40 amplification cycles of 90 °C for 15 seconds then 60 °C for 1 minute. Postreaction dissociation analysis was performed to confirm single-product amplification. The transcripts per cell calculation was made using a value of 142.7 cell equivalents per 5 ng of RNA.

Production and purification of ET-801i: Briefly, ET-801i producer cells were cultured in 500 cm2 flasks containing AIM-V serum-free medium. Conditioned medium was harvested, frozen at −80 °C, and replaced daily for 7 days. For each day of production, fVIII activity and activation quotient were assayed to monitor production rate and material quality. Following the production run, conditioned media was pooled, assayed for fVIII activity, and ET-801i was isolated using a one-step ion-exchange chromatography procedure similar to that described previously7 and in Figure 5. Briefly, conditioned medium containing ~128,750 units of ET-801i was loaded onto a 2.5 × 19.5 cm SP-Sepharose Fast Flow column equilibrated at 25 °C in 0.18 mol/l NaCl, 20 mmol/l HEPES, 5 mmol/l CaCl2, 0.01% Tween-80, pH 7.4. ET-801i was eluted using a linear 0.18–0.7 mol/l NaCl gradient in the same buffer. Fractions containing fVIII activity were pooled and stored at −80 ºC.

Efficacy of ET-801i: After determination of body weight, hemophilia A mice were placed on a heating pad for ~5 minutes to dilate the tail veins and then were injected with vehicle alone (HEPES-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-80) or ET-801i in vehicle at a dose of 290 units/kg. Immediately after the injection, anesthesia was induced with 4% isoflurane at a flow of 1,000 ml/min using an RC2 Rodent Circuit Controller (Vet-Equip, Pleasanton, CA) for 5 minutes and then decreased to 2% isoflurane at a flow rate of 500 ml/minute. Tails were placed into a 15-ml conical tube containing 13 ml of normal saline at 37 ºC. At 15 minutes, 4 mm of the distal tail was transected using a scalpel. The tail then was placed into a new 15-ml conical tube containing 13 ml of saline at 37 ºC. Following the tail-snip, the anesthesia was reduced to 2% isoflurane and a flow rate of 500 ml/minute, which was maintained for the remainder of the experiment. The amount of blood loss into the tube in 40 minutes or at the time of death from hemorrhage was recorded as mg of blood loss per gram of body weight.

Statistical analysis: Linear regression analysis was performed using SigmaPlot for Windows Version 10.0 (Systat Software, Chicago, IL). Tests for significant correlation of parameters were performed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and two-tailed Student's t-distribution. Comparisons between groups were made using the Mann–Whitney U test.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Clonal Analysis of BHK-M Cells Expressing ET801i. In an independent experiment, BHK-M cells were transduced with ET-801i encoding lentivirus vector at an MOI 20. A total of 53 individual clones were isolated by limiting serial dilution. Each clone was analyzed for ET-801i production by one-stage coagulation assay. Figure S2. Southern Blot (a) and Northern Blot (b) Analysis of ET801i Expressing Clones. (a) Southern blot analysis of 5 μg of genomic DNA digested with AvrII was performed. A cell line with a known proviral copy number of 3 was used as a positive control, while untransduced BHK-M genomic DNA served as negative control. (b) Northern blot analysis was performed on 5 μg of total RNA. A DIG-labeled probe against the porcine A1 domain was used for both analyses. Figure S3. FVIII Production from ET801i Expressing 3-10 Sub-Clones. A total of 18 subclones (grey bars) were isolated by limiting serial dilution from parental BHK-M clone 3-10 (black bar) and analyzed for ET-801i production by one-stage coagulation assay. Figure S4. Interaction of ET-801i with vWf. A microtiter plate was coated with human vWf, blocked and then incubated with dilutions of human fVIII (circles) or ET-801i (squares) ranging from 0 – 1 nM. The plates then were washed and residual fVIII (indicative of being bound to vWf) was detected using a monoclonal antibody that specifically binds an epitope in the human fVIII A2 domain. Figure S5. FVIIIa decay analysis of ET-801i. Highly-purified preparations of h-fVIII (closed circles) and ET-801i (open circles) were activated by addition of thrombin. After a 30 sec incubation, thrombin activity was inhibited by addition of desulfatohirudin and fVIIIa activity was determined as described previously 1. Data are expressed as fraction (f) of initial fVIIIa activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keith W. Kerstann and Rachel T. Barrow for technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to C.B.D. (HL090112). C.B.D., H.T.S., and P.L. are cofounders and hold equity positions in Expression Therapeutics, LLC, which owns the intellectual property for high-expression fVIII technology. G.D. and R.E.G. are employees of Expression Therapeutics, LLC. B.D. is a cofounder and holds an equity position in Lentigen Corporation, which owns the intellectual property for lentiviral vectors. B.D., A.R., and L.B. are employees of Lentigen Corporation.

Supplementary Material

Clonal Analysis of BHK-M Cells Expressing ET801i. In an independent experiment, BHK-M cells were transduced with ET-801i encoding lentivirus vector at an MOI 20. A total of 53 individual clones were isolated by limiting serial dilution. Each clone was analyzed for ET-801i production by one-stage coagulation assay.

Southern Blot (a) and Northern Blot (b) Analysis of ET801i Expressing Clones. (a) Southern blot analysis of 5 μg of genomic DNA digested with AvrII was performed. A cell line with a known proviral copy number of 3 was used as a positive control, while untransduced BHK-M genomic DNA served as negative control. (b) Northern blot analysis was performed on 5 μg of total RNA. A DIG-labeled probe against the porcine A1 domain was used for both analyses.

FVIII Production from ET801i Expressing 3-10 Sub-Clones. A total of 18 subclones (grey bars) were isolated by limiting serial dilution from parental BHK-M clone 3-10 (black bar) and analyzed for ET-801i production by one-stage coagulation assay.

Interaction of ET-801i with vWf. A microtiter plate was coated with human vWf, blocked and then incubated with dilutions of human fVIII (circles) or ET-801i (squares) ranging from 0 – 1 nM. The plates then were washed and residual fVIII (indicative of being bound to vWf) was detected using a monoclonal antibody that specifically binds an epitope in the human fVIII A2 domain.

FVIIIa decay analysis of ET-801i. Highly-purified preparations of h-fVIII (closed circles) and ET-801i (open circles) were activated by addition of thrombin. After a 30 sec incubation, thrombin activity was inhibited by addition of desulfatohirudin and fVIIIa activity was determined as described previously 1. Data are expressed as fraction (f) of initial fVIIIa activity.

REFERENCES

- Garber K. rFactor VIII deficit questioned. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1133. doi: 10.1038/81098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ, Pipe SW, Tagliavacca L, Swaroop M., and, Moussalli M. Biosynthesis, assembly and secretion of coagulation factor VIII. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8 Suppl 2:S3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaroop M, Moussalli M, Pipe SW., and, Kaufman RJ. Mutagenesis of a potential immunoglobulin-binding protein-binding site enhances secretion of coagulation factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24121–24124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao HZ, Sirachainan N, Palmer L, Kucab P, Cunningham MA, Kaufman RJ, et al. Bioengineering of coagulation factor VIII for improved secretion. Blood. 2004;103:3412–3419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering CB, Denning G, Dooriss K, Gangadharan B, Johnston JM, Kerstann KW, et al. Directed engineering of a high-expression chimeric transgene as a strategy for gene therapy of hemophilia A. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1145–1154. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering CB, Healey JF, Parker ET, Barrow RT., and, Lollar P. High level expression of recombinant porcine coagulation factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38345–38349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering CB, Healey JF, Parker ET, Barrow RT., and, Lollar P. Identification of porcine coagulation factor VIII domains responsible for high level expression via enhanced secretion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6546–6552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering CB, Healey JF, Parker ET, Barrow RT., and, Lollar P. High level expression of recombinant porcine coagulation factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38345–38349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker ET, Healey JF, Barrow RT, Craddock HN., and, Lollar P. Reduction of the inhibitory antibody response to human factor VIII in hemophilia A mice by mutagenesis of the A2 domain B-cell epitope. Blood. 2004;104:704–710. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey JF, Parker ET, Barrow RT, Langley TJ, Church WR., and, Lollar P. The comparative immunogenicity of human and porcine factor VIII in haemophilia A mice. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:35–41. doi: 10.1160/TH08-12-0818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G., and, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering C, Parker ET, Healey JF, Craddock HN, Barrow RT., and, Lollar P. Expression and characterization of recombinant murine factor VIII. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:450–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boedeker BG. Production processes of licensed recombinant factor VIII preparations. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:385–394. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lollar P., and, Parker CG. pH-dependent denaturation of thrombin-activated porcine factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1688–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lollar P., and, Parker ET. Structural basis for the decreased procoagulant activity of human factor VIII compared to the porcine homolog. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12481–12486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lollar P, Parker ET., and, Fay PJ. Coagulant properties of hybrid human/porcine factor VIII molecules. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23652–23657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipe SW, Eickhorst AN, McKinley SH, Saenko EL., and, Kaufman RJ. Mild hemophilia A caused by increased rate of factor VIII A2 subunit dissociation: evidence for nonproteolytic inactivation of factor VIIIa in vivo. Blood. 1999;93:176–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipe SW, Saenko EL, Eickhorst AN, Kemball-Cook G., and, Kaufman RJ. Hemophilia A mutations associated with 1-stage/2-stage activity discrepancy disrupt protein-protein interactions within the triplicated A domains of thrombin-activated factor VIIIa. Blood. 2001;97:685–691. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker ET, Doering CB., and, Lollar P. A1 subunit-mediated regulation of thrombin-activated factor VIII A2 subunit dissociation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13922–13930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooriss KL, Denning G, Gangadharan B, Javazon EH, McCarty DA, Spencer HT, et al. Comparison of factor VIII transgenes bioengineered for improved expression in gene therapy of hemophilia A. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:465–478. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitschier J, Wood WI, Goralka TM, Wion KL, Chen EY, Eaton DH, et al. Characterization of the human factor VIII gene. Nature. 1984;312:326–330. doi: 10.1038/312326a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clonal Analysis of BHK-M Cells Expressing ET801i. In an independent experiment, BHK-M cells were transduced with ET-801i encoding lentivirus vector at an MOI 20. A total of 53 individual clones were isolated by limiting serial dilution. Each clone was analyzed for ET-801i production by one-stage coagulation assay.

Southern Blot (a) and Northern Blot (b) Analysis of ET801i Expressing Clones. (a) Southern blot analysis of 5 μg of genomic DNA digested with AvrII was performed. A cell line with a known proviral copy number of 3 was used as a positive control, while untransduced BHK-M genomic DNA served as negative control. (b) Northern blot analysis was performed on 5 μg of total RNA. A DIG-labeled probe against the porcine A1 domain was used for both analyses.

FVIII Production from ET801i Expressing 3-10 Sub-Clones. A total of 18 subclones (grey bars) were isolated by limiting serial dilution from parental BHK-M clone 3-10 (black bar) and analyzed for ET-801i production by one-stage coagulation assay.

Interaction of ET-801i with vWf. A microtiter plate was coated with human vWf, blocked and then incubated with dilutions of human fVIII (circles) or ET-801i (squares) ranging from 0 – 1 nM. The plates then were washed and residual fVIII (indicative of being bound to vWf) was detected using a monoclonal antibody that specifically binds an epitope in the human fVIII A2 domain.

FVIIIa decay analysis of ET-801i. Highly-purified preparations of h-fVIII (closed circles) and ET-801i (open circles) were activated by addition of thrombin. After a 30 sec incubation, thrombin activity was inhibited by addition of desulfatohirudin and fVIIIa activity was determined as described previously 1. Data are expressed as fraction (f) of initial fVIIIa activity.