Abstract

It is unclear whether siRNA-based agents can be a safe and effective therapy for diseases. In this study, we demonstrate that microphthalmia-associated transcription factor–siRNA (MITF-siR)-silenced MITF gene expression effectively induced a significant reduction in tyrosinase (TYR), tyrosinase-related protein 1, and melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) levels. The siRNAs caused obvious inhibition of melanin synthesis and melanoma cell apoptosis. Using a novel type of transdermal peptide, we developed the formulation of an MITF-siR cream. Results demonstrated that hyperpigmented facial lesions of siRNA-treated subjects were significantly lighter after 12 weeks of therapy than before treatment (P < 0.001); overall improvement was first noted after 4 weeks of siRNA treatment. At the end of treatment, clinical and colorimetric evaluations demonstrated a 90.4% lightening of the siRNA-treated lesions toward normal skin color. The relative melanin contents in the lesions and adjacent normal skin were decreased by 26% and 7.4%, respectively, after treatment with the MITF-siR formulation. Topical application of siRNA formulation significantly lightens brown facial hypermelanosis and lightens normal skin in Asian individuals. This treatment represents a safe and effective therapy for melasma, suggesting that siRNA-based agents could be developed for treating other diseases such as melanoma.

Introduction

Melasma is a common disorder of cutaneous hyperpigmentation predominantly affecting the faces of women. Because it is refractory and recurrent, it is often difficult to treat.1,2 Depigmenting agents are commonly prescribed; inhibition of tyrosinase (TYR) is the most common approach to achieving skin hypopigmentation.1,2,3,4,5 Many TYR inhibitors have been identified in vitro, but few exert therapeutic effects in clinical trials. Among the skin-lightening and spot-removing agents are hydroquinone, tretinoin (retinoic acid), kojic acid (KA), azelaic acid, arbutin, and glabridin. These agents are well known among dermatologists but can cause unsightly depigmentation, irritant dermatitis and ochronosis.3,6,7 Innovative strategies are required to identify new drug targets and to develop potent agents. With the advent of new technologies such as siRNA and antisense, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), and other related genes could become candidates for a new generation of depigmenting agents.

MITF acts as a master regulator of melanocyte development, function and survival.8 Mutation causes Waardenburg syndrome type IIA and results in premature loss of melanocyte stem cells, retinal pigmented epithelium, mast cells, and osteoclasts.8,9,10 MITF is thought to mediate significant effects of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone on differentiation by transcriptionally regulating enzymes that are essential for melanin production, i.e., TYR, tyrosinase-related protein 1 and TYR-related protein-2/dopachrome-tautomerase. The promoters of these genes contain the MITF consensus E-box sequence and can be activated by MITF.11 Within the past decade, MITF has been described as a highly sensitive immunohistochemical marker for the diagnosis of melanoma; as a transcriptional activator of T-box transcription factor, it is required for melanoma cell proliferation.12 It regulates the expression of the antiapoptotic factor BCL213 and has been reported to modulate the c-MET promoter directly, and c-MET has been linked to the metastatic potential of melanomas.14 Moreover, there are indications that MITF regulates several other genes including melanoma-1, associated with human oculocutaneous albinism type IV, and melanoma antigen, recognized by T-cells 1.15,16 Information gleaned from studies concerning MITF in melanocytes may contribute to therapeutic advances in melasma and melanoma.

RNA interference is a general mechanism for silencing active gene transcripts (mRNAs). This posttranscriptional gene silencing process is initiated by small interfering RNA (siRNA), a double-stranded RNA that contains 21–23 base pairs and is highly specific for the nucleotide sequence of its target mRNA. 17,18 Recently, siRNA technology has become widely used for the systematic analysis of gene function, and its potential therapeutic applications have been under intense investigation.17,18,19,20 For siRNA therapeutics, however, safe, stable, and efficient delivery issues are major obstacles for clinical application.21 In this study, 31 patients were treated for pigmented facial lesions using an MITF-siRNA (MITF-siR) cream with highly efficient transdermal vehicles. The curative efficacy and safety of this treatment on melasma were analyzed and evaluated. MITF-siR cream could be an effective and reliable treatment for hyperpigmentation disorders and melanoma.

Results

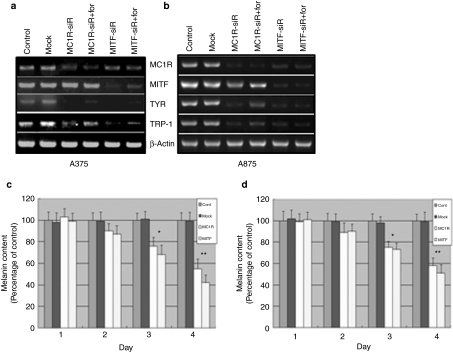

The effects of chemically modified MITF-siR on the expression of melanogenic genes

The silencing efficiency of MITF-siR on target mRNAs was assessed. reverse transcriptase–PCR demonstrated that target mRNAs were down-regulated to different extents in A375 and A875 cells; 10 nmol/l mutant siRNA was ineffective, confirming that the siRNA specifically induced target mRNA silencing (Figure 1a,b). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that transfection of siRNA against MC1R or MITF resulted in a significant dose-dependent decrease in the corresponding mRNA (Figure 1a,b). To enhance the stability of the siRNAs and compare related delivery technologies, chemically modified and cholesterol-conjugated siRNAs (MITF-siR* and MITF-siR+) were employed. Reverse transcriptase–PCR analysis indicated that 10 nmol/l of melanocortin 1 receptor siRNA+ (MC1R-siR) or MITF-siR* encapsulated with TD1-R8 peptide effectively inhibited the expression of their cognate mRNAs (Figure 1c,d). Therefore, this chemical modification did not alter the biological activities of the siRNAs. However, quantitative comparison revealed that the siRNAs* transfected with TD1-R8 peptide were superior to the cholesterol-conjugated siRNAs+ (Figure 1c,d). Therefore, to suppress target mRNAs effectively and lower siRNA toxicity, 10 nmol/l of chemically modified siRNAs were used for experiments unless otherwise indicated.

Figure 1.

Melanocortin 1 receptor siRNA (MC1R-siR) and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA (MITF-siR) significantly inhibit expression of their target genes. (a) When grown to 70% confluence in 6-well plates, melanoma cells were transfected with mock siRNA or MC1R-siR at concentrations of 5 nmol/l or 10 nmol/l for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to Trizol treatment. Reverse transcriptase–PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. β-Actin levels were a control for RNA loading. Relative levels of the expressed mc1r and β-actin mRNAs under various conditions were determined and normalized to their levels in the buffer control. Data are representative experiments performed in triplicate and are displayed as mean and SD. (b) Reverse transcriptase–PCR and quantitative analysis were employed for the MITF-siR case. (c) Reverse transcriptase–PCR to detect mc1r mRNA levels was performed on total RNAs from untreated melanoma cells (Control) or treated for 24 hours with mock siRNA or chemically modified MC1R-siR* plus TD1-R8 peptide or cholesterol conjugated MC1R-siR+ (Chol) alone. (d) The same protocol was used for the chemically modified MITF-siR* case.

To decipher the molecular mechanism by which MITF regulates melanogenesis, the effect of MITF-siR on mc1r, tyr, and trp1 promoter activities was examined. Interestingly, MITF-siR significantly reduced the levels of MC1R, TYR and TRP1 (Figure 2a,b). However, endogenous β-actin expression remained unaltered, suggesting that this MITF-siR was sequence-specific for MITF mRNA and that transcription of mc1r, tyr, and trp1 were reduced because they are targets of MITF. In contrast, MC1R gene silencing did not effectively abrogate mitf expression. We subsequently tested whether forskolin, a cell-permeable diterpenoid that activates adenyl cyclase, reversed the effect of MITF-siR. Surprisingly, the inhibition of TYR and TRP1 promoter activities by MITF-siR was not rescued by 40 µmol/l forskolin after 6 hours, although the effect of MC1R-siR was partially reversed. Moreover, comparative analysis demonstrated no differences in mc1r, tyr, or trp1 expression between the cases treated with MITF-siR and those treated with a combination of MITF-siR and forskolin. These results suggest that MITF-siR is a more effective inhibitor of melanogenic genes than MC1R-siR.

Figure 2.

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA (MITF-siR) significantly inhibits the expression of melanogenic genes and the synthesis of melanin in A375 and A875 melanoma cells. When (a) A375 and (b) A875 melanoma cells were at 70–80% confluence, they were transfected with 10 nmol/l mock siRNA or melanocortin 1 receptor siRNA (MC1R-siR) or MITF-siR for 24 hour, then treated without or with forskolin (for) at 40 µmol/l for a further 6 hours. Reverse transcriptase–PCR was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. β-Actin levels were used as controls for RNA gel loading. A375 (c) and A875 (d) cells were treated once without or with the different siRNAs at 10 nmol/l. The melanin content was measured at different time points. Bars represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments, each using duplicate culture flasks. *Significantly different from the nontreated control group at P < 0.01. **Significantly different from the untreated control group at P < 0.001.

The effects of chemically modified MITF-siR and depigmenting agents on melanin synthesis

To determine whether melanin synthesis was affected by MITF-siR, melanin content was measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. Total melanin was extracted from A375 and A875 cells treated once for different days with 10 nmol/l MC1R-siR or MITF-siR. Buffer and mock siRNA pools were used as controls. Quantitative analysis demonstrated significant differences in melanin content between siRNA-treated and untreated melanoma cells. MC1R-siR and MITF-siR decreased the melanin yield to ~50% of that in controls (Figure 2c,d). Interestingly, both siRNAs induced a time-dependent inhibition of melanin formation. This implies that these depigmenting agents would be more effective if the treatment time was prolonged, confirming their ability to modulate pigmentation.

To compare the inhibitory effects of different depigmenting agents, different siRNAs such as MC1R-siR, MITF-siR*, and MC1R-siR* were employed at a concentration of 10 nmol/l. Buffer and mock siRNA pools were employed as controls. Quantitative analysis demonstrated that 3 days after transfection, all four siRNAs resulted in a significant inhibition on melanin formation (Figure 3). Moreover, chemically modified siRNAs* had a greater effect on the suppression of melanin yield than unmodified siRNAs; this could be due to increased stability and the longer activity of these modified siRNAs*. To obtain maximal inhibitory effects on melanin generation and a reduction in side effects, KA and arbutin were employed at doses less than the safe recommendation of 1% prescription in the topical application of these depigmenting agents.22 A375 and A875 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing KA, β-arbutin, or α-arbutin at a concentration of 10 mmol/l. An acid-insoluble fraction was prepared from cells cultured for 4 days and the amount of melanin was measured. Melanin synthesis was slightly inhibited by β-arbutin, while KA and α-arbutin caused a notable decrease in the melanin content compared to nontreated cells (Figure 3). Comparative analysis of the inhibitory effects provoked by these depigmenting agents illustrated that MITF-siR* was superior to MC1R-siR*, KA, and β-arbutin.

Figure 3.

Depigmenting agents inhibit the synthesis of melanin in A375 and A875 melanoma cells. Nine pools of melanoma cells were treated once with different agents such as different siRNAs at 10 nmol/l or other agents at 10 mmol/l, respectively. Three days after transfection, the cells were analyzed to determine the melanin content. Each tube contained 1 × 106 cells. The melanin content of melanoma cells treated with buffer was the control. Bars represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments, each using duplicate culture flasks. *Significantly different from the nontreated control group at P < 0.05. **Significantly different from the untreated control group at P < 0.001. MC1R-siR, melanocortin 1 receptor siRNA; MC1R-siR*, chemically modified melanocortin 1 receptor siRNA; MITF-siR, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA; MITF-siR*, chemically modified microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA.

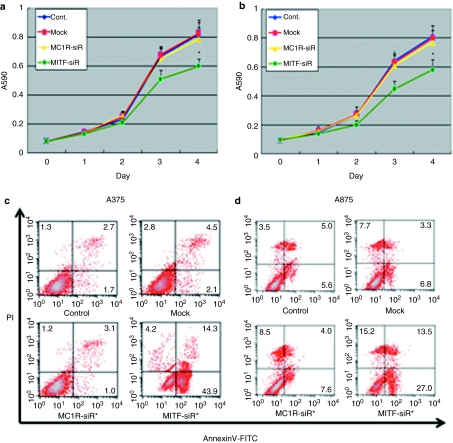

The effects of chemically modified MITF-siR on melanoma cell apoptosis

To investigate whether the siRNAs used had an effect on the proliferation and apoptosis of A375 and A875 cells, the melanoma cells were transfected once a day for 3 days with MC1R-siR, MITF-siR, or mock siRNA. At different time points, the transfected cells were stained with MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) to observe alterations in cell growth. As shown in Figure 4a,b, 10 nmol/l mock siRNA and MC1R-siR had no effect on cell viability, but the same dose of MITF-siR significantly reduced the number of cells on the fourth day. To clarify whether this relative decrease was due to apoptosis, annexin V/propidium iodide-stained cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (Figure 4c,d). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis demonstrated that apoptosis began in the transfected melanoma cells 24 hours after transfection and continued thereafter. On the fourth day of treatment, the MITF-siR group was significantly different from the control and mock groups; no difference was detected between the control and MC1R-siR groups. These data support the view that MITF is involved in melanin synthesis as well as the survival of cells of the melanocytic lineage, and that MITF silencing using siRNA inhibits melanoma growth.23

Figure 4.

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA (MITF-siR) inhibits cell viability and induces apoptosis of melanoma cells. (a) A375 and (b) A875 melanoma cells were treated once per day for 3 days without or with different siRNAs at 10 mmol/l. Viabilities (a and b) and apoptosis (c and d) of the treated melanoma cells were determined using MTT assay and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Each point represents the mean ± SD Significant differences in cell viability between controls and agent-treated groups are indicated by #P < 0.01 or **P < 0.001. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; MC1R-siR, melanocortin 1 receptor siRNA.

To re-examine whether KA and arbutin cause inhibition of cell growth, A375 and A875 cells were treated with 5 mmol/l KA or arbutin once a day for 3 days and assayed at different time points. In comparison to melanoma cells grown in medium alone, remarkable changes in growth were observed in melanoma cell lines treated with KA or arbutin. Surprisingly, KA and α-arbutin caused a significant inhibition of cell survival, with the growth rate fivefold lower than control pools (Figure 4a,b). This inhibitory effect became more apparent after two treatments with KA or arbutin, suggesting that this dose of the whitening agents is toxic to cells.

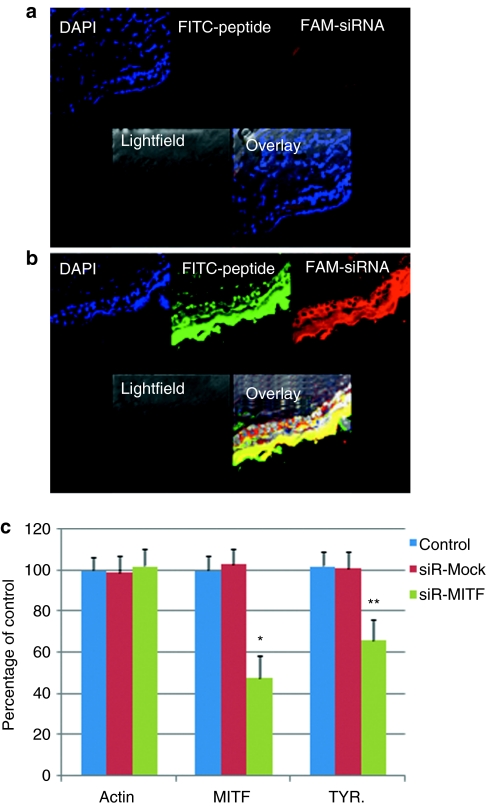

The transdermal peptide

To investigate whether the peptide TD1-R8 aided MITF-siR to penetrate the stratum corneum and distribute throughout the skin of mice, the fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled peptide and carboxyfluorescein-labeled MITF-siR were used as markers. The cream formulation (100 µg), with or without the peptide, was applied topically to hair-clipped BALB/c mouse skin. Although the chemically modified siRNAs were located throughout the whole epidermis and partial dermis after 2 hours, there was only slight accumulation in the skin of the formulation without peptides (Figure 5a,b). In addition, there was an intense fluorescent signal of peptide in the epidermis and the dermis. These data suggest that the penetration peptide in the cream formulation is required to support the trafficking of siRNA from the surface of skin to the epidermis and dermis.

Figure 5.

The transdermal peptide strongly facilitates the entry of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA (MITF-siR) into the epidermis and dermis of mice. Fluorescence photomicrographs after topical application of MITF-siR cream formulation to hair-clipped BALB/c mouse skin after 2 hours. Pictures taken at ×40 magnification under a laser scanning confocal microscope. (a) A group of pictures for the group treated with naked siRNAs; (b) a group of pictures for the group treated with peptide-coated siRNA. Three animals were evaluated for each group; the micrographs show a representative section from one animal. Bar = 20 µm. (c) MITF-siR cream effectively inhibits MITF expression in vivo. Real-time PCR was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. β-Actin levels were used as controls for RNA loading. Bars represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments, each using duplicate mouse skin sized 1.5 × 0.2 cm2. * and **, significantly different from those in the mock group at P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; TYR, tyrosinase.

Topical treatment with siMITF cream was tested to determine whether it attenuated the expression of MITF mRNA in mouse skin. Groups of three BALB/c mice with the back hair shaved were tested. The first group served as a naive control, whereas the second group received a cream with mutant siRNA and peptide TD1-R8 and served as a negative control. Animals in the third group were treated with siMITF and TD1-R8 once per day. A thin layer of the different creams (without or with mock or MITF-siR) was smeared on the mouse skin once per day for 3 days, and related skin samples were used to analyze the changes in mitf and TYR genes. Real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that siMITF-treated mice had significantly lower expression of MITF mRNA than the control group or the group receiving mutant siMITF and TD1-R8 (Figure 5c). On the fourth day, mouse skin exhibited a 52% and 34% decrease in MITF and TYR mRNA levels, respectively (versus naive control). In contrast, mutant siRNA caused no change in the expression of MITF or TYR above naive levels.

Clinical evaluation

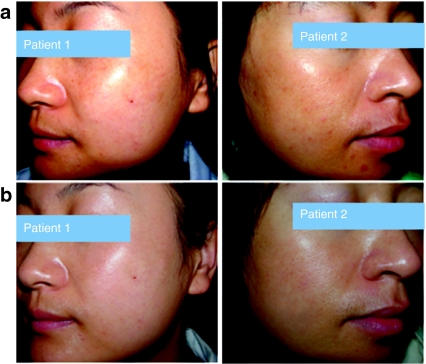

Overall evaluation after treatment with magnesium--ascorbyl-2-phosphate (VC-PMG) or MITF-siR cream demonstrated significant improvement in the skin lesions compared to adjacent normal skin (Figure 6; P < 0.05 or P < 0.001). In the MITF-siR group, the facial lesions of six of the 31 siRNA-treated subjects (19.4%) were classified as cured, 11 (35.5%) as much lighter, 11 (35.5%) as lighter, and 3 as unchanged compared to adjacent normal skin after 12 weeks of treatment. No subject had lesions that were evaluated as worse or much worse. Overall lightening of the lesions was noted as early as 4 weeks after the beginning of treatment (P < 0.05) (Figure 7a) and became increasingly evident throughout the study. In addition, only one of the 31 subjects had moderate erythema, which disappeared after the agent was discontinued. However, this subject demonstrated total improvement when treatment was resumed. In the VC-PMG group, the facial lesions of 5 of the 25 were classified as much lighter whereas 13 were unchanged. The total efficiency rate was 20% in the VC-PMG group, which was significantly lower than the MITF-siR group.

Figure 6.

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA (MITF-siR) cream significantly improves the images from two patients with facial melasma. (a) Before treatment. (b) After 12 weeks of treatment with MITF-siR cream, with lightening of pigmentation.

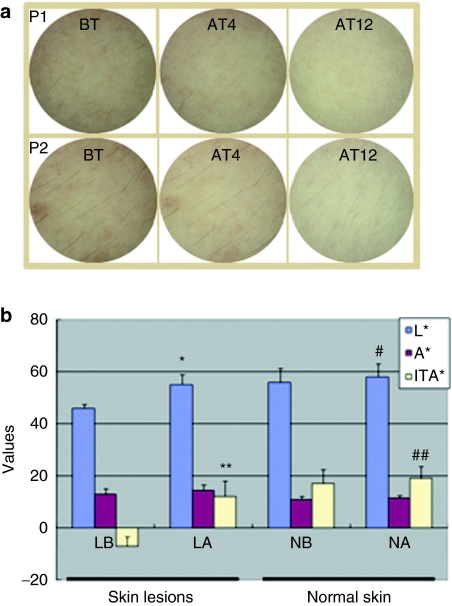

Figure 7.

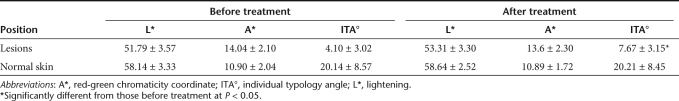

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-siRNA (MITF-siR) cream effectively inhibits melanin synthesis in vivo. (a) Dermoscopic pictures of melasma lesion before treatment (BT), and after 4 weeks (AT4) or 12 weeks (AT12) of treatment, showing complete improvement of skin lesions accompanied by lightening of the skin. P1 and P2 indicate patients 1 and 2, respectively. (b) Lightening (L*), red-green chromaticity coordinate (a*) and individual typology angle (ITA°) values for skin color changes before and after treatment. LB and LA refer to skin lesions before and after 12 weeks of treatment with MITF-siR cream; NB and NA refer to normal skin before and after 12 weeks of treatment, respectively. * and **, significantly different from those before treatment at P < 0.001. # and ##, significantly different from those before treatment at P < 0.05.

The clinical lightening of the designated hyperpigmented malesma lesions after treatment with the siRNA cream was significantly greater than before treatment (clinical scores, 2.677 ± 0.475 versus 1.126 ± 0.786; P ≤ 0.01). Dermoscopy demonstrated an increase in lightening (L*) value of 7.5 ± 1.5 units in lesions treated with siRNA cream, compared to an increase of 1.4 ± 1.2 units in adjacent normal skin (P ≤ 0.01) (Figure 7a,b). The average baseline L* value for all lesions was 46.9 ± 1.2 units, and the corresponding average for normal skin was 56.1 ± 1.6 units, a difference of ~10 units. Therefore, after 12 weeks of treatment with MITF-siR cream, the L* value was 75% closer to the value for normal skin. The relative melanin contents in the lesions and adjacent normal skin were decreased by 26% and 7.4%, respectively, with MITF-siR. The change in the color of the lesions measured by colorimetry at week 12 correlated closely with the color change noted on clinical evaluation.

The individual typology angle (ITA°) of the skin lesions (Figure 7b) was significantly higher after (10.39 ± 7.05) than before (–7.63 ± 3.56) treatment (P < 0.001), and the ITA° value of adjacent normal skin was also higher after (18.76 ± 7.42) than before (17.23 ± 7.47) treatment (P <0.05). More importantly, in six patients showing complete improvement, the ITA° values of the skin lesions after treatment ranged from 21.62 to 25.88, compared to normal skin values ranging from 21.16 to 27.15. Moreover, the comparison of outcomes throughout the treatment with MITF-siR and VC-PMG creams (Table 1) demonstrated that the former had a better curative effect on melasma. These data suggest that topical treatment with MITF-siR cream is a safe and efficient therapy for facial melasma.

Table 1. Dermoscopic data from melasma patients before and after treatment with PC-PMG.

Discussion

Many studies have investigated TYR inhibitors,1,2,3,4,5,6,7 but few have considered whether MITF can be used as a drug target for treating hyperpigmentation disorders. This study has demonstrated that MITF-siR has specific effects, not only inhibiting the production of MITF and its downstream melanogenic genes such as tyr and trp1 in melanoma cells, but also suppressing melanin synthesis in vitro and in vivo. In addition, this study underlined that the interaction or cooperation of MITF and cAMP responsiveness in the promoter region of TYR and TRP1 genes is essential and sufficient for their normal expression. To date, few studies have concluded that the interaction of MITF and cAMP responsiveness is required for basal expression of TYR and TRP1 genes. Furthermore, no research has as yet dissected or identified a direct relationship accounting for the extent of MC1R gene expression and the transcriptional activities of MITF. This research attempted to clarify these important issues as the results presented herein are the first to provide direct evidence that MITF or MC1R alone cannot maintain the basal expression of TYR and TRP1 genes, and that silencing of the mc1r gene causes a significant inhibition of TYR and TRP1 expression but not MITF. In addition, we demonstrate that irrespective of high or low levels of MC1R receptor, elevated intracellular cAMP triggered by forskolin leads to potent induction of the TYR and TRP1 promoters with the assistance of MITF, but does not reverse the inhibitory effects of MITF-siR on the expression of tyr and trp1 genes. Therefore, these data are the first to demonstrate that MITF-siR, a negative modulator of MITF, can be used as a depigmenting agent.

The in vivo application of siRNA is severely limited by the effectiveness of the delivery system.17,19,20,21 Recently, bioactive oligoarginine and a transdermal peptide capable of condensing nucleic acids and penetrating the skin have attracted considerable attention.24,25,26,27 This study is the first to demonstrate that conjugating TD1 to R8 covalently can be a powerful way to deliver siRNAs into the epidermis and dermis of mammals. The higher efficacy of the MITF-siR cream formulation could be due to the ionic interactions between R7 and siRNA, aided by TD1 creating a transient opening in the skin to facilitate access of the siRNA to melanocytes. Though the precise mechanism has yet to be elucidated, these findings suggest that this new approach could aid the future development of siRNA drugs for other cutaneous disorders.

The present study was performed using a combination of colorimetric assessments and visual inspection for melasma ratings, a reasonable approach to quantifying the skin condition of melasma.28,29,30 The results demonstrated a good or excellent response in 90.4% of facial melasma patients after treatment with MITF-siR cream. Of 31 patients, three demonstrated no satisfactory improvement. The bias could be due to the extent of melasma, patient responses and courses of treatment. Objective measures provided some support. The results demonstrated that changes in L* in the pigmented facial lesions were predominantly due to changes in the amount of melanin, because red-green chromaticity coordinate (a*) did not change significantly in the majority of patients. The alterations can be used to judge the efficacy of a treatment for pigmented lesions, whereas the difference between a lesion and the normal area is regarded as an indicator of improvement.30,31,32 Sanchez et al.33 described a dermal type of melasma as having melanin-laden macrophages in the perivascular array, in both the papillary and reticular dermis. The epidermal type generally responds well to topical therapy, whereas predominant dermal melanin deposition responds poorly. Clinical observation indicated that the three recalcitrant patients in this study could suffer from this condition. Although MITF-siR was delivered into the dermis, the efficacy of siRNA transfection requires further improvement. The findings from this research suggest that this siRNA cream is an effective method for treating the epidermal type of melasma, but there is a requirement to develop more efficient delivery vehicles.

Improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying the regulation of melanogenesis should facilitate the development of new drugs for medical application. In this study, a novel type of topical MITF-siR cream was demonstrated to be an effective and safe treatment modality for Asian patients suffering with facial hypermelanosis. MITF-siR significantly inhibited melanin synthesis and melanoma growth, and had no major side effects. Therefore, it is a promising therapeutic agent for the prevention and treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders and malignant melanoma. It is reasonable to expect improved results in melasma patients subjected to daily administration of an improved MITF-siR cream formulation at a high dosage over a longer time-course.

Materials and Methods

Melanin, KA (2-hydroxymethyl-5-hydroxy-γ-pyrone), forskolin, and arbutin (4-hydroxyphenyl-β--glucopyranoside) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). α-Arbutin (4-hydroxyphenyl-α--glucopyranoside) was purchased from Pentapharma (Basel, Switzerland). Arbutin and α-arbutin were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to a final concentration of 10 mmol/l in culture medium, and KA was added directly to the culture medium.

Synthesis of siRNAs. RNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by Genepharm (Shanghai, China) and purified by anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography. To generate siRNAs from RNA single strands, equimolar amounts of complementary sense and antisense strands were mixed and annealed, and siRNAs were further characterized by native gel electrophoresis. Each freeze-dried siRNA was reconstituted with RNase-free water to produce a 20 mmol/l stock solution for further experiments.

The siRNA sequences used for targeted silencing of human mc1r and Mitf were designed as previously described.34 The target sequence was localized at position 190, or 98 bases downstream of the start codon from human Mc1r and Mitf mRNA sequences, respectively (GenBank accession no. NM_002386 and BC065243). The following sequences were used to target MC1R and MITF: MC1R-1-siR: sense 5′-CCAAGAACCGGAACCUGCUTT–3′ chemically modified MC1R-1-siR*: sense 5′-C*C* AAGAACCGGAACCUG*C*U*TT-3′ and antisense 5′-AGCAGGUUCCGGUUCUUG*G*TT–3′ MITF-siR: sense 5′-GCAGUACCUUUCUACCACUTT-3′ chemically modified MITF-siR*: sense 5′-G*C*AGUACCUUUCUACCA*C*U*TT-3′ and antisense 5′-AGUGGUAGAAAGGUACUG*C*TT-3′. For nonsilencing control siRNAs, a mutant MITF-siR was used as mock-siR. Mock-siR: antisense 5′-GGCUCUAGAAAAGCCUAUG*C*TT-3′.

Cell culture and transfection. Human melanoma cell lines A375 and A875 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Tumor cells (3 × 105) cultured in each well of a six-well plate were treated with buffer alone for the control group. Transfection of siRNAs or mock siRNAs was performed with Genofectin (Geno Biotech, Beijiing, http://www.geno-bio.cn) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to a previous method.35 All experiments were performed four times.

Determination of cell viability and melanin production in melanoma cells. A total of 8 × 103 A375 or A875 melanoma cells were seeded in each well of 96-well plate and allowed to attach for 18 hours in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cells were treated with or without various siRNAs between one and three times. On days 1, 2, 3, or 4 of culture, cell viability was analyzed by the MTT (Sigma) assay.35 The optical density was determined using a microculture plate reader (3550; Bio-Rad, Beijing, China) at 590 nm. Absorbance values were normalized to the values obtained for control cases to determine the percentage of survival.

In order to extract melanin from the A375 or A875 melanoma cells, 1 ml of cell suspension containing 106 cells was shaken with an equal volume of a mixture containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and 1 N NaOH, at 80 °C for 60 minutes. After centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 10 minutes, the melanin content was determined at 475 nm using the SpectroQuest Reader (Unico, Holbrook, NY). Melanin levels were quantified from a standard curve. Depigmentation activity was represented by the percentage of melanin content in treated A375 cells compared to that in untreated A375 cells. The assay was carried out in triplicate and on three separate occasions.

Reverse transcriptase–PCR. A375 and A875 cells were treated with the indicated reagents for 3 consecutive days. On day 4, total RNA from the cells was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using oligo d(T)15 primer and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase. The resulting cDNA was subjected to PCR amplification with specific primers (1 µmol/l each) in 20 µl aliquots. Primers used for PCR were; left primer 5′-TGC TGATG GACTCCGGTGAC-3′ and right primer 5′-CGCCAGA CAGCACTGTGT TG-3′ for β-actin, left primer 5′-GGCGTGATCTTCTTCCCCTT-3′ and right primer 5′-CAGACCTCC CGATCATCTCT-3′ for TRP-1, left primer 5′-TTTGTACTGC CTGCTGTGGA-3′ and right primer 5′-TGTGCAGT TTGGTCCCCAA-3′ for TYR, left primer 5′-CGGGTCTCTGCTCTCCA GA-3′ and right primer 5′-CCGGCTGCTTGTTTTGG AA-3′ for MITF, and left primer 5′-TGGTGAGCTTGGTGGAGAA-3′ and right primer 5′-TGGTCGTAGTAGGCGATGAA-3′ for MC1R. Generally, 30 amplification cycles (94 °C for 45 seconds, 55 °C for 30 seconds, and 72 °C for 30 seconds) were performed using Promega Taq DNA polymerase, and the PCR products were subjected to 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Cycle numbers were optimized in several experiments with determination of the linear phase of the PCR.

Flow cytometry. Cultured cells were treated with various vectors or regents. On day 2 after transfection, apoptotic cells were detected by Annexin V-PE and propidium iodide double labeling. The procedure was performed following the manufacturer's instruction. Flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was used to assess the apoptotic cells.

In vivo mouse dermal delivery. Because the short synthetic peptide ACSSSPSKHCG (TD1) and oligoarginine (R8) have been shown to facilitate efficient bio-macromolecule delivery through intact skin,36,37,38,39 we developed a new peptide by conjugating TD1 and R8, and employed this peptide (TD1-R8), ACSSSPSKHCGGRRRRRRRR, to deliver siRNA to the skin. TD1-R8 peptide was synthesized and labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate in vitro by Geno Biotechnology (Beijing, China). MITF-siR was synthesized and labeled with carboxyfluorescein for different cases by Genepharm.

Eight-week-old animals (Animal Center of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing, China) were used in this study. All studies were conducted utilizing protocols and methods approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals were provided food and water ad libitum and kept on a 12 hours light/dark cycle.

BALB/c mice were hair-clipped the day before the experiment, while avoiding cuts to the skin, and cream was applied to the clipped area 24 hours later. Approximately 100 µg of cream containing 0.005% MITF-siR was applied over an area of ~4 cm2 on the dorsal surface of the skin. The formulation was evenly smeared onto the skin to ensure uniform distribution. After 30 minutes of treatment, application sites were cleaned of residual cream with a mild surfactant (5% glycerol). Five animals were killed by exsanguination per group and skin samples were collected. For control formulations, the cream without transdermal peptide and/or siRNA was applied to the skin.

Histological evaluation. After 2 hours of treatment, mouse skin containing different creams was obtained and placed in a labeled cryomold and covered with OCT (OCT Compound VWR cat. no. 25608–25930). The mold containing the skin was gently submerged in a prechilled Dewar flask containing liquid nitrogen/dry ice slurry for ~1 minute until the OCT turned white and opaque. Tissue was stored in a −70 °C freezer until sections were cut. Tissue was at a temperature of −20 °C before cutting in a Leica CM 3050 cryostat (Leica, Northvale, NJ) into 5 mm sections. Sections were picked up on “t” superfrost slides and allowed to air dry for 4 hours, fixed in 5% neutral buffered formalin for 5 minutes, rinsed in distilled water to remove formalin, and mounted in Aquamount for fluorescent visualization using the TCS-SL confocal microscope system (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Patients and design. Fifty-six healthy Chinese subjects (7 men and 49 women, 27–48 years old; mean age 38) with moderate-to-severe postinflammatory hyperpigmentation lesions on their faces were enrolled in the study. The patients were divided into two groups; the first group comprised 31 patients treated with 0.005% MITF-siR cream and the second group received a 10% magnesium--ascorbyl-2-phosphate cream. The mean course of disease was 3 years. No subject had used topical medications (including hydroquinones or corticosteroids) for at least 4 weeks prior to the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects after the potential side effects of the agents had been explained to them. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the General Hospital of the Air Force.

Clinical evaluation. The therapeutic effects were evaluated clinically at the first visit (before treatment, day 0), the second visit (week 4) and at the end of the trial (week 12). At the first visit the history of melasma, its duration, relationship to pregnancy, hormonal therapy, sun exposure, and cosmetic use were recorded. Patients were asked about previous use of hydroquinones and the family history of melasma. The treated areas were evaluated before and after 0.005% MITF-siR or 10% magnesium--ascorbyl- 2-phosphate cream treatment. The presence and degree of melasma were clinically verified and registered in the case report form, treated sites being specified and the intensity of the melasma graded on a 4-point semi-quantitative scale: 0, absent; (i) slight darkness, with the melasma area >2 cm2; (ii) moderate darkness, with the area >2–4 cm2; (iii) severe darkness, with the area >4 cm2. The index of treatment success was calculated by subtracting the total posttreatment score from the total pretreatment score and expressing the difference as a percentage of the pretreatment score. An index of treatment success of >90% was graded as basic cure; >60% was graded as significant improvement; >30% was graded as improvement; <30% was graded as no effect.

The side effects of erythema and desquamation were rated at all visits on a scale of 0 (side effects absent) to 4 (side effects most severe); subjects were classified as having an MITF-siR reaction if they had a score of 2 or more for erythema or desquamation at two or more visits.

Dermoscope. The designated melasma hyperpigmentation lesions and normal skin surrounding them were assessed with a colorimeter (Microskin II Polarized-light dermoscope and digital image analysis system, Motic China Group, China) before treatment and after 4 and 12 weeks of therapy. After the objective dermoscopy lens was brought parallel to the skin lesion surface, and polarized light was adjusted on to the optimal point to record the lesions. Normal skin color adjacent to the tested area was measured as a control. The measurement procedure followed the L* a* b* (b*: yellow-blue chromaticity coordinate) mode in accordance with Efficacy Measurements on Cosmetics and Other Topical Products recommendations.31 The mean values of eight measurements were recorded for each subject before and after treatment. The value of L* was taken as an indicator of the degree of pigmentation, or the amount of melanin in the skin, and the so-called individual typology angle (ITA° ITA° = Arc Tangent [(L*−50)/b*] × 180/3.14159) was used to reveal the total color change in the designated lesions.

ITA° has a theoretical range of −30° (pure black) to 55° (pure white), and can be used to interpret the skin phenomena involved objectively. Colorimetry was used to obtain an objective, quantifiable measure of MITF-siR-induced lightening of the melasma hyperpigmentation lesions and to determine whether the colorimetric findings correlated with the clinical assessments of each subject.

Variations in the amounts of melanin. To determine the efficacy of treatment, the L*a*b* values of the small pigmented lesions and adjacent normal skin were measured simultaneously, and the difference between lesion and normal area was regarded as the indicator of improvement. Of these three parameters, a* and L* can be used to demonstrate skin color changes. The degree of pigmentation, or the amount of melanin in the skin, is normally estimated in terms of L*. The differences in values between the test sites and their corresponding controls, a* test site—a* ctrl (δa*) and L* test site —L*ctrl (δL*) were calculated. It has been indicated that δMel = −1.06 δa*−1.44 δL* is appropriate for estimating the change in the relative amount of melanin (Mel).32

Treatment. The chemically modified MITF-siR cream (5 mg MITF-siR in 100 g cream) was supplied by the Department of Pharmacy, General Hospital of the Air Force. To formulate the cream, MITF-siR was incubated with arginine-rich peptide (TD1-R8) at a 1:8 molar ratio for 20 minutes at room temperature in 5% glucose, and mixed with a cream composed of glyceryl monostearate (10%), liquid paraffin wax (10%), methylparaben (0.5%), propylparaben (0.5%), polyoxyl-40-stearate (15%), silicone oil DC 200 (0.5%), water, and emulsifier. The subjects applied this medication twice daily for 3 months to the entire face, depending on the sites of the lesions. They were instructed to apply a pea-sized amount and to increase the amount gradually unless undue irritation developed. Subjects were asked to avoid excessive exposure to sunlight, wind, and cold. Cosmetics were not to be used during the period of treatment.

Statistical analysis. The means and SDs of L*, a* and ITA° were calculated using SPSS 13.0. The two-tailed paired Student's t-test was used for intra-individual comparisons of colorimetric values between the lesioned skin and adjacent normal skin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CAS “Hundred Talents Program”, the 863 program (grant no. 2008AA02Z122) and NSFC (grant no. 30871250).

REFERENCES

- Cestari T, Arellano I, Hexsel D., and, Ortonne JP, Latin American Pigmentary Disorders Academy Melasma in Latin America: options for therapy and treatment algorithm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:760–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Gover MD, Nouri K., and, Taylor S. The treatment of melasma: a review of clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1048–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvez S, Kang M, Chung HS, Cho C, Hong MC, Shin MK, et al. Survey and mechanism of skin depigmenting and lightening agents. Phytother Res. 2006;20:921–934. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafal ES, Griffiths CE, Ditre CM, Finkel LJ, Hamilton TA, Ellis CN, et al. Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) treatment for liver spots associated with photodamage. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:368–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202063260603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern RS. Clinical practice. Treatment of photoaging. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1526–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp023168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torok HM, Jones T, Rich P, Smith S., and, Tschen E. Hydroquinone 4%, tretinoin 0.05%, fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%: a safe and efficacious 12-month treatment for melasma. Cutis. 2005;75:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draelos ZD. Skin lightening preparations and the hydroquinone controversy. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:308–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AJ., and, Mihm MC., Jr Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:51–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steingrímsson E, Copeland NG., and, Jenkins NA. Melanocytes and the microphthalmia transcription factor network. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:365–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassabehji M, Newton VE., and, Read AP. Waardenburg syndrome type 2 caused by mutations in the human microphthalmia (MITF) gene. Nat Genet. 1994;8:251–255. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemesath TJ, Steingrímsson E, McGill G, Hansen MJ, Vaught J, Hodgkinson CA, et al. microphthalmia, a critical factor in melanocyte development, defines a discrete transcription factor family. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2770–2780. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance KW, Carreira S, Brosch G., and, Goding CR. Tbx2 is overexpressed and plays an important role in maintaining proliferation and suppression of senescence in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2260–2268. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill GG, Horstmann M, Widlund HR, Du J, Motyckova G, Nishimura EK, et al. Bcl2 regulation by the melanocyte master regulator Mitf modulates lineage survival and melanoma cell viability. Cell. 2002;109:707–718. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill GG, Haq R, Nishimura EK., and, Fisher DE. c-Met expression is regulated by Mitf in the melanocyte lineage. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10365–10373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., and, Fisher DE. Identification of Aim-1 as the underwhite mouse mutant and its transcriptional regulation by MITF. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:402–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Miller AJ, Widlund HR, Horstmann MA, Ramaswamy S., and, Fisher DE. MLANA/MART1 and SILV/PMEL17/GP100 are transcriptionally regulated by MITF in melanocytes and melanoma. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:333–343. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63657-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y., and, Tuschl T. On the art of identifying effective and specific siRNAs. Nat Methods. 2006;3:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nmeth911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leachman SA, Hickerson RP, Schwartz ME, Bullough EE, Hutcherson SL, Boucher KM, et al. First-in-human mutation-targeted siRNA phase Ib trial of an inherited skin disorder. Mol Ther. 2010;18:442–446. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley CR, Seow Y., and, Wood MJ. Novel RNA-based strategies for therapeutic gene silencing. Mol Ther. 2010;18:466–476. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshayes S, Morris M, Heitz F., and, Divita G. Delivery of proteins and nucleic acids using a non-covalent peptide-based strategy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL., and, Linsley PS. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder RM., and, Richards GM. Topical agents used in the management of hyperpigmentation. Skin Therapy Lett. 2004;9:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynek JN, Chan SM, Liu J, Zha J, Fairbrother WJ., and, Vucic D. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor is a critical transcriptional regulator of melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3124–3132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futaki S, Suzuki T, Ohashi W, Yagami T, Tanaka S, Ueda K, et al. Arginine-rich peptides. An abundant source of membrane-permeable peptides having potential as carriers for intracellular protein delivery. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5836–5840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil IA, Futaki S, Niwa M, Baba Y, Kaji N, Kamiya H, et al. Mechanism of improved gene transfer by the N-terminal stearylation of octaarginine: enhanced cellular association by hydrophobic core formation. Gene Ther. 2004;11:636–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won YW, Kim HA, Lee M., and, Kim YH. Reducible poly(oligo-D-arginine) for enhanced gene expression in mouse lung by intratracheal injection. Mol Ther. 2010;18:734–742. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar RL, McLean WH., and, Schwartz ME. Achieving successful delivery of nucleic acids to skin: 6th Annual Meeting of the International Pachyonychia Congenita Consortium. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2085–2087. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K., and, Binder M. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:159–165. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarys P, Alewaeters K, Lambrecht R., and, Barel AO. Skin color measurements: comparison between three instruments: the Chromameter®, the DermaSpectrometer® and the Mexameter®. Skin Res Technol. 2000;6:230–238. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0846.2000.006004230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Westerhof W, Im S., and, Lim J. Noninvasive techniques for the evaluation of skin color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54 5 Suppl 2:S282–S290. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piérard GE. EEMCO guidance for the assessment of skin colour. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;10:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0926-9959(97)00183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiwaki H, Miyaoka Y, Kohno H., and, Arase S. Graphic analysis of the relationship between skin colour change and variations in the amounts of melanin and haemoglobin. Skin Res Technol. 2002;8:78–83. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0846.2002.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, Fitzpatrick TB, Sanchez JL., and, Mihm MC., Jr Melasma: a clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:698–710. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin JQ, Gao J, Shao R, Tian WN, Wang J., and, Wan Y. siRNA agents inhibit oncogene expression and attenuate human tumor cell growth. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2003;3:194–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-4117.2003.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TG, Yin JQ, Shang BY, Min Z, He HW, Jiang JM, et al. Silencing of hdm2 oncogene by siRNA inhibits p53-dependent human breast cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:748–756. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Wu H, McBride JL, Jung KE, Kim MH, Davidson BL, et al. Transvascular delivery of small interfering RNA to the central nervous system. Nature. 2007;448:39–43. doi: 10.1038/nature05901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Shen Y, Guo X, Zhang C, Yang W, Ma M, et al. Transdermal protein delivery by a coadministered peptide identified via phage display. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:455–460. doi: 10.1038/nbt1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Kim NY, Choi YB, Park SH, Yang JM., and, Shin S.2010RNA interference in vitro and in vivo using an arginine peptide/siRNA complex system J Control Releaseepub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yin H, Moulton HM, Seow Y, Boyd C, Boutilier J, Iverson P, et al. Cell-penetrating peptide-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides restore systemic muscle and cardiac dystrophin expression and function. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3909–3918. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]