Abstract

It is widely accepted that the conversion of the soluble, nontoxic amyloid β-protein (Aβ) monomer to aggregated toxic Aβ rich in β-sheet structures is central to the development of Alzheimer's disease. However, the mechanism of the abnormal aggregation of Aβ in vivo is not well understood. Accumulating evidence suggests that lipid rafts (microdomains) in membranes mainly composed of sphingolipids (gangliosides and sphingomyelin) and cholesterol play a pivotal role in this process. This paper summarizes the molecular mechanisms by which Aβ aggregates on membranes containing ganglioside clusters, forming amyloid fibrils. Notably, the toxicity and physicochemical properties of the fibrils are different from those of Aβ amyloids formed in solution. Furthermore, differences between Aβ-(1–40) and Aβ-(1–42) in membrane interaction and amyloidogenesis are also emphasized.

1. Introduction

It is widely accepted that the amyloid β-protein (Aβ), which exists in fibrillar forms as a major component of senile plaques, is central to the development of Alzheimer's disease (AD) [1, 2]. The conversion of soluble, nontoxic Aβ monomer to aggregated toxic Aβ rich in β-sheet structures ignites the neurotoxic cascade(s) of Aβ [3]. The mechanism of the abnormal aggregation of Aβ is not well understood. The physiological concentration of Aβ in biological fluids (<10−8 M) [4] is much lower than the concentration (~1 μM) above which Aβ-(1–40) spontaneously forms fibrils [5]. Therefore, there should be mechanisms that facilitate the abnormal aggregation of Aβ under pathological conditions. Although clusterin (Apo J) [6] and Zn2+ ions [7] were reported to facilitate the aggregation of Aβ more than a decade ago, their aggregation-promoting mechanisms are yet to be elucidated. In addition to these soluble factors, Jarrett and Lansbury, Jr. suggested that Aβ fibrillizes via a nucleation-dependent polymerization mechanism and lipids could act as heterogeneous seeds for the polymerization [8]. In 1995, Yanagisawa and colleagues discovered a specific form of Aβ bound to monosialoganglioside GM1 (GM1) in brains exhibiting early pathological changes of AD and suggested that the GM1-bound form of Aβ may serve as a seed for the formation of toxic amyloid aggregates/fibrils [9].

We have been investigating the interaction of Aβ with ganglioside-containing membranes for a dozen years and found that not the uniformly distributed but the clustered gangliosides mediate the formation of amyloid fibrils by Aβ, the toxicity and physicochemical properties of which are different from those of Aβ amyloids formed in solution. This review article summarizes Aβ-ganglioside interaction in detail, including latest findings that were not covered in our previous reviews [10, 11]. Especially, differences between Aβ-(1–40) and Aβ-(1–42) in membrane interaction and amyloidogenesis are extensively discussed. Furthermore, a link between Aβ aggregation and lipid metabolism is emphasized. It will shed light on one of the initiation processes of AD.

2. Specific Binding of Aβ to Ganglioside Clusters

Early studies indicated that Aβ-(1–40) associates with GM1 in egg yolk phosphatidylcholine (PC) vesicles only when the GM1 content exceeds 30% [12, 13]. The threshold GM1 content is lowered in a sphingomyelin (SM)/cholesterol mixture [13]. These findings suggest that GM1 molecules only in a specific state can recognize Aβ. To reveal the underlying mechanism, we systematically investigated the interaction of dye-labeled-Aβ-(1–40) [14–16] and -Aβ-(1–42) [17] with membranes of various lipid compositions. The N-termini of Aβs were labeled with the 7-diethylaminocoumarin-3-carbonyl group (DAC-Aβ). DAC-Aβ is useful for fluorometrically monitoring protein-lipid interactions, because a significant blue shift and an enhancement in intensity are induced by a change in polarity upon membrane binding. DAC-Aβs do not bind to major membrane lipids, including electrically neutral PC, SM, cholesterol, negatively charged phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylglycerol under physiological conditions. On the other hand, the proteins exhibit similar high affinity (binding constant ~107 M−1) for raft-like membranes composed of GM1, cholesterol, and SM [14, 15]. DAC-Aβ-(1–28) also has a weak affinity for the membrane [16]. Binding parameters are summarized in Table 1. DAC-Aβ-(1–40) also binds to other gangliosides (GD1a, GD1b, GT1b, and asialo GM1) and lactosyl ceramide in raft-like membranes with higher affinity for lipids having larger sugar chains [15, 16]. We have proposed that Aβs specifically bind to ganglioside clusters because a GM1 cluster is formed in GM1/SM/cholesterol membranes but not in GM1/PC membranes. The clustering is facilitated by cholesterol [14].

Table 1.

Parameters for the binding of DAC-Aβs to GM1/cholesterol/SM (1 : 1 : 1) LUVs at 37°C.

| Aβ | K (106 M−1)a | xmaxb(Aβ/GM1, mol/mol) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAC-Aβ-(1–42) | 11.1 ± 2.4 | 0.0361 ± 0.0021 | [17] |

| DAC-Aβ-(1–40) | 8.6 ± 3.6 | 0.0313 ± 0.0041 | [16] |

| DAC-Aβ-(1–28) | 0.0184 ± 0.0007 | 0.0313c | [16] |

aBinding constant.

bMaximal value of x (bound Aβ per exofacial GM1, mol/mol).

cAssumed to be the same as that of DAC-Aβ-(1–40).

3. Fibrillization by Aβ on Ganglioside Clusters

Aβ-(1–40) bound to ganglioside clusters assumes different conformations depending on the protein density on the membrane. Circular dichroism measurements revealed that the protein forms an α-helix-rich structure at lower protein-to-ganglioside ratios (≤0.025) whereas it changes its conformation to a β-sheet-rich structure at higher ratios (≥0.05) [14, 15]. Aβ-(1–42) also undergoes similar conformational changes [17]. Only the β-sheet form facilitates amyloidogenesis by Aβ-(1–40) [15, 18–20].

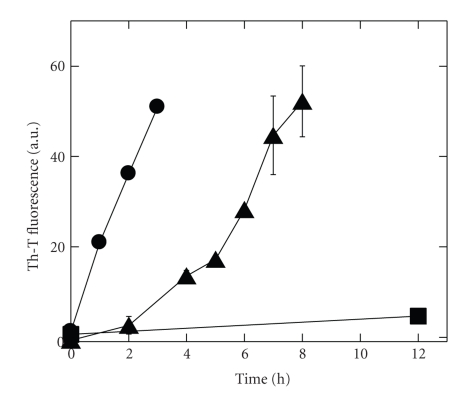

Despite very similar initial protein-ganglioside interaction, that is, the binding behavior and the α-helix-to-β-sheet conformational change, a large difference was observed in amyloidogenic activity (amount of amyloids formed under certain conditions) between Aβ-(1–40) and Aβ-(1–42) [17]. Aβs were incubated with GM1/cholesterol/SM liposomes at a Aβ-to-GM1 ratio of 5, and the aggregation of Aβ was monitored as an increase in fluorescence of the amyloid-specific dye thioflavin-T (Th-T) (Figure 1). Aβ-(1–42) formed amyloids without a lag time at 5 μM. In contrast, Aβ-(1–40) at 5 μM did not form amyloids, at least not in 12 h. At a 10-fold higher concentration, Aβ-(1–40) started to aggregate after a lag time of ~2 h. The effectiveness of Aβ-(1–42) in fibrillogenesis is at least partly due to the fragility of fibrils, because the fragmentation greatly facilitates fibril growth [21] (see also Section 5). Other factors, such as the rapid formation of seeds and/or elongation, may also contribute to the difference.

Figure 1.

Aβ aggregation in the presence of raft-like liposomes. Aβs (5 μM or 50 μM) were incubated with GM1/cholesterol/SM (1 : 1 : 1) small unilamellar vesicles at a GM1-to-Aβ ratio of 5 at 37°C without agitation, and the aggregation was monitored by the Th-T assay. Symbols: circles, 5 μM Aβ-(1–42); squares, 5 μM Aβ-(1–40); triangles, 50 μM Aβ-(1–40). Data taken from [17].

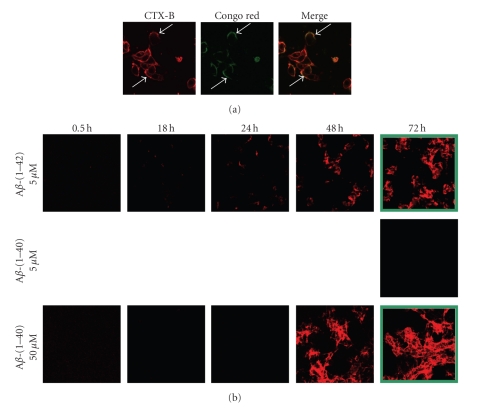

Cell experiments also support the above mechanism of Aβ-ganglioside interaction [22, 23]. Aβ-(1–42) was incubated with neuronal rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. Amyloids and gangliosides were detected by the amyloid-specific dye Congo red and the fluorescent-labeled cholera toxin B subunit, respectively. Amyloids were selectively formed on ganglioside-rich domains (Figure 2(a)). Depletion of cholesterol, either by methyl-β-cyclodextrin or the cholesterol synthesis inhibitor compactin, suppressed the accumulation of Aβ. The amyloidogenic activity of Aβ-(1–42) was again more than 10-fold that of Aβ-(1–40) on human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells expressing gangliosides (Figure 2(b)). When cells were incubated with 5 μM Aβ-(1–42), Congo red-positive spots appeared later at 24 h and became prominent with time. In contrast, when cells were incubated with 5 μM Aβ-(1–40), no fibrils were detected even after 72 h. Incubation with a 10-fold higher concentration of the protein, however, resulted in the appearance of Congo red-positive spots at 48 h.

Figure 2.

Aβ aggregation on living neuronal cells. (a) Aβ-(1–42) (10 μM) was incubated with PC12 cells for 24 h at 37°C. The distribution of GM1 was detected by using the cholera toxin B subunit conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 dye (CTX-B, left). Amyloids were visualized by the amyloid-specific dye Congo red (middle). The merging of the two images shows that amyloids were formed in the vicinity of GM1-rich domains of cell membranes (right). Data taken from [10]. (B) Ganglioside-expressing SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with 5 μM Aβ-(1–42) (top), 5 μM Aβ-(1–40) (middle), or 50 μM Aβ-(1–40) (bottom) for 0.5, 18, 24, 48, or 72 h, and the formation of amyloids was detected with Congo red. The conditions under which cell death was observed are framed in green. Data taken from [17].

4. Properties of Aβ Fibrils Formed on Ganglioside Clusters

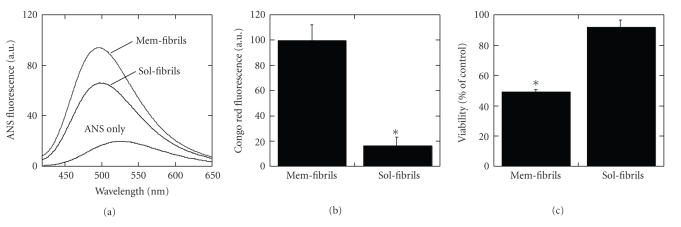

The Aβ fibrils formed on ganglioside clusters (Mem-fibrils) are not identical to those formed in solution (Sol-fibrils) in terms of physicochemical properties and cytotoxicity [20]. Transmission electron micrographs indicate that Mem-fibrils are typical nonbranched fibrils (12.0 ± 0.7 nm, width) whereas Sol-fibrils are thinner fibrils or protofilaments (6.7 ± 1.3 nm, width), and the protofilaments associate laterally and twist into rope-like fibrils (14.5 ± 0.9 nm, width). The surface hydrophobicity of Mem-fibrils as estimated by the binding of 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonate (ANS) is larger than that of Sol-fibrils (Figure 3(a)), therefore Mem-fibrils exhibit significantly stronger binding to cell membranes than Sol-fibrils (Figure 3(b)). Consequently, Mem-fibrils are cytotoxic whereas Sol-fibrils are much less toxic (Figure 3(c)). Recently, a correlation between ANS-binding and cytotoxicity was reported for various amyloid species [24].

Figure 3.

Comparison between Mem-fibrils and Sol-fibrils. Data taken from [20]. (a) Fluorescence spectra of ANS (5.0 μM) in PBS were measured in the absence or presence of Mem-fibrils and Sol-fibrils of Aβ-(1–40) (2.5 μM) with an excitation wavelength of 350 nm. The binding of the dye to a hydrophobic surface results in an enhancement in fluorescence intensity. (b) Aβ-(1–40) fibrils (25 μM) were incubated with NGF-differentiated PC12 cells for 30 min. Binding of Aβ-(1–40) fibrils to cells was evaluated by fluorescence intensity of Congo red per cell (mean ± S.E.; n ~ 100, *P < .001). (c) Aβ-(1–40) fibrils (25 μM) were incubated with NGF-differentiated PC12 cells for 24 h. Aβ cytotoxicity was estimated with fluorescence intensity of the live cell marker calcein (mean ± S.E.; n = 6; *P < .001 against vehicle treatment).

The structure of Mem-fibrils is suggested to be different from that of Sol-fibrils, in which the cross-β unit is a double-layered structure, with in-resister parallel β-sheets formed by residues 12–24 and 30–40 [25]. The amide I spectrum of the former shows, in addition to a major peak around 1630 cm−1 characteristic of a β-sheet, a weak peak at 1695 cm−1 whereas that of the latter shows a peak around 1660 cm−1 [26].

5. Mechanism of Cytotoxicity by Aβ Fibrils Formed on Ganglioside Clusters

The mechanisms of Aβ-induced cytotoxicity have been controversial. Aβ fibrils were reported to trigger functional disorder in neuronal cells and cell death [27–31] whereas soluble Aβ oligomers have been proposed to play a pivotal role in the onset of AD [6, 28, 32–39]. To obtain an insight into the cytotoxic mechanism of Aβ, we established a multistaining visualization method using unlabeled Aβs and antibodies [17] in contrast to conventional methods using fluorophore-labeled proteins [23, 40]. The accumulation of Aβ, the formation of amyloid fibrils, the formation of oligomers, and cell viability were visualized using the Aβ monoclonal antibody 6E10, the amyloid-staining dye Congo red [22], the antioligomer antibody A11 [34], and calcein acetoxymethyl, respectively. Cell death was detected after the significant accumulation of fibrils (Figure 2(b)) and no A11-positive spot was detected, suggesting that fibril-induced physicochemical stress, such as the induction of a negative curvature [13] or membrane deformation upon fibril growth [41], leads to cytotoxicity. A11-positive oligomers were not formed in the fibrillization with GM1-containing liposomes either [20]. It should be noted, however, that at certain GM1 contents GM1-liposomes generate toxic soluble Aβ-(1–40) oligomers [42]. For both Aβs, similar levels of fibrils were required for cytotoxicity (Figure 2(b)), indicating that the fibrils possess comparable intrinsic toxicity. The fibrillization process and cytotoxicity can be effectively blocked by small compounds, such as nordihydroguaiaretic acid and rifampicin [19].

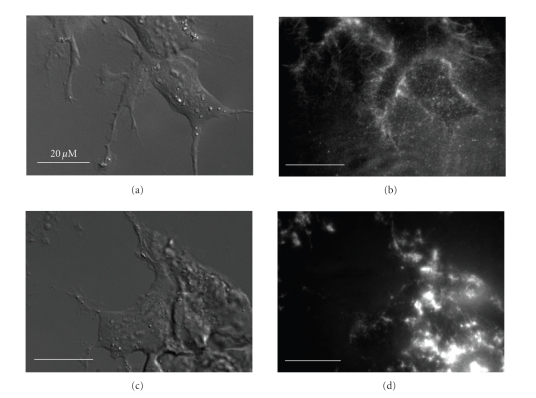

The morphology of amyloid fibrils formed on cell membranes was visualized by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) [17]. TIRFM effectively reduces the background fluorescence and therefore is suitable for observing the cell surface. Fibrils were stained with Congo red. Relatively long fibrillar structures were detected around the cell membrane for Aβ-(1–40) whereas relatively short fibrils were coassembled in the case of Aβ-(1–42) (Figure 4). The latter observation suggests that Aβ-(1–42) fibrils are more readily fragmented. The fragmentation greatly facilitates fibril growth because fibrils grow only at their ends [21].

Figure 4.

Visualization of amyloid fibrils formed on cell membranes using TIRFM. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 50 μM Aβ-(1–40) ((a), (b)) or 5 μM Aβ-(1–42) ((c), (d)) for 48 h. Amyloid fibrils were stained with 20 μM Congo red. (a) and (c) are DIC images, while (b) and (d) are TIRF images. Data taken from [17].

6. Concluding Remarks

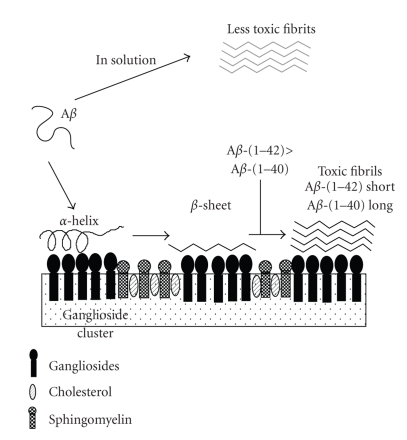

Based on the above observations, we propose a novel model for Aβ-membrane interaction as a mechanism for the abnormal aggregation of the protein (Figure 5). Aβ specifically binds to a ganglioside cluster, the formation of which is facilitated by cholesterol. The cluster can be formed also by late endocytic dysfunction [43]. The Aβ undergoes a conformational transition from an α-helix-rich structure to a β-sheet-rich one with increasing protein density on the membrane. The β-sheet form serves as a seed for the formation of amyloid fibrils, which are more toxic than and have different structures from those formed in solution. Depending on ganglioside contents in the membrane, toxic soluble oligomers may also be generated. The amyloidogenic activity of Aβ-(1–42) is more than 10-fold that of Aβ-(1–40), although the initial interaction with gangliosides is similar between the two proteins.

Figure 5.

A model for the formation of toxic amyloid fibrils by amyloid β-protein on ganglioside clusters. Aβ is essentially soluble, and takes an unordered structure in solution. Once ganglioside clusters are generated, Aβ binds to the clusters, forming an α-helix-rich structure at lower protein-to-ganglioside ratios whereas the protein changes its conformation to a β-sheet at higher ratios. The β-sheet form facilitates the fibrillization of Aβ, leading to cytotoxicity. The amyloidogenic activity of Aβ-(1–42) is more than 10-fold that of Aβ-(1–40). Amyloid fibrils formed in solution are much less toxic.

This model can explain roles of various risk factors in the pathogenesis of AD, especially from a viewpoint of lipid metabolism. Both the aging and the apolipoprotein E4 allele are strong risk factors for developing AD [44]. The amount of cholesterol in the exofacial leaflets of the synaptic plasma membrane increases in aged [45] as well as apolipoprotein E4-knock-in [46] mice. GM1 clustering occurs at presynaptic neuritic terminals in mouse brains in an age-dependent manner [47]. Diet-induced hypercholesterolemia accelerates the amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model [48]. A link between cholesterol, Aβ, and AD has been reported [49, 50]. Human AD brains also show abnormality in lipid metabolism in accordance with our model [51, 52]. That is, significant increase in GM1 was reported in Aβ-positive nerve terminals from the AD cortex [51], and lipid rafts from the frontal cortex and the temporal cortex of AD brains were also found to contain a higher concentration of GM1 compared to an age-matched control [52]. It should be noted that, in addition to these modulations of Aβ aggregation by lipids, Aβ also in turn regulates lipid metabolism [53].

The 10-fold higher amyloidogenic activity of Aβ-(1–42) is in accordance with the facts (1) that genetic mutations in the presenilins causing early-onset AD increase the level of Aβ-(1–42) [54] and (2) that the protein is the major species in diffuse plaques, the earliest stage in the deposition of Aβ [55].

In conclusion, in addition to other biochemical cascades, a complex purely physicochemical cascade linked to lipid metabolism (Figure 5) appears to be also involved in the process of Aβ aggregation. Inhibition of one of these steps would be a promising strategy for AD therapy.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (22-14) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG), Japan.

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(2):741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Citron M. Alzheimer’s disease: treatments in discovery and development. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:1055–1057. doi: 10.1038/nn940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256(5054):184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Esch F, et al. Isolation and quantification of soluble Alzheimer’s β-peptide from biological fluids. Nature. 1992;359(6393):325–327. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Nuallain B, Shivaprasad S, Kheterpal I, Wetzel R. Thermodynamics of Aβ(1–40) amyloid fibril elongation. Biochemistry. 2005;44(38):12709–12718. doi: 10.1021/bi050927h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1−42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(11):6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush AI, Pettingell WH, Multhaup G, et al. Rapid induction of Alzheimer Aβ amyloid formation by zinc. Science. 1994;265(5177):1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.8073293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT. Seeding ’one-dimensional crystallization’ of amyloid: a pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease and scrapie? Cell. 1993;73(6):1055–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanagisawa K, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Ihara Y. GM1 ganglioside-bound amyloid β-protein (Aβ): a possible form of preamyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine. 1995;1(10):1062–1066. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuzaki K. Physicochemical interactions of amyloid β-peptide with lipid bilayers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1768(8):1935–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuzaki K, Kato K, Yanagisawa K. Aβ polymerization through interaction with membrane gangliosides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2010;1801(8):868–877. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaurin J, Franklin T, Fraser PE, Chakrabartty A. Structural transitions associated with the interaction of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides with gangliosides. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(8):4506–4515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuzaki K, Horikiri C. Interactions of amyloid β-peptide (1–40) with ganglioside-containing membranes. Biochemistry. 1999;38(13):4137–4142. doi: 10.1021/bi982345o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakio A, Nishimoto SI, Yanagisawa K, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K. Cholesterol-dependent formation of GM1 ganglioside-bound amyloid β-protein, an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(27):24985–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakio A, Nishimoto SI, Yanagisawa K, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K. Interactions of amyloid β-protein with various gangliosides in raft-like membranes: importance of GM1 ganglioside-bound form as an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. Biochemistry. 2002;41(23):7385–7390. doi: 10.1021/bi0255874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeda K, Matsuzaki K. Driving force of binding of amyloid β-protein to lipid bilayers. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;370(3):525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogawa M, Tsukuda M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Ganglioside-mediated aggregation of amyloid β-proteins (Aβ): comparison between Aβ-(1–42) and Aβ-(1–40) doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06997.x. Journal of Neurochemistry. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi H, Kimura N, Yamaguchi H, et al. A seed for Alzheimer amyloid in the brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(20):4894–4902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0861-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuzaki K, Noguch T, Wakabayashi M, et al. Inhibitors of amyloid β-protein aggregation mediated by GM1-containing raft-like membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1768(1):122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada T, Ikeda K, Wakabayashi M, Ogawa M, Matsuzaki K. Formation of toxic Aβ(1–40) fibrils on GM1 ganglioside-containing membranes mimicking lipid rafts: polymorphisms in Aβ(1–40) fibrils. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008;382(4):1066–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowles TPJ, Waudby CA, Devlin GL, et al. An analytical solution to the kinetics of breakable filament assembly. Science. 2009;326(5959):1533–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1178250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakabayashi M, Matsuzaki K. Formation of amyloids by Aβ-(1-42) on NGF-differentiated PC12 cells: roles of gangliosides and cholesterol. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;371(4):924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakabayashi M, Okada T, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K. GM1 ganglioside-mediated accumulation of amyloid β-protein on cell membranes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;328(4):1019–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolognesi B, Kumita JR, Barros TP, et al. ANS binding reveals common features of cytotoxic amyloid species. ACS Chemical Biology. 2010;5(8):735–740. doi: 10.1021/cb1001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tycko R. Insights into the amyloid folding problem from solid-state NMR. Biochemistry. 2003;42(11):3151–3159. doi: 10.1021/bi027378p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakio A, Yano Y, Takai D, et al. Interaction between amyloid β-protein aggregates and membranes. Journal of Peptide Science. 2004;10(10):612–621. doi: 10.1002/psc.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(35):32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deshpande A, Mina E, Glabe C, Busciglio J. Different conformations of amyloid β induce neurotoxicity by distinct mechanisms in human cortical neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(22):6011–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1189-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grace EA, Rabiner CA, Busciglio J. Characterization of neuronal dystrophy induced by fibrillar amyloid β: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2002;114(1):265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jana A, Pahan K. Fibrillar amyloid-β peptides kill human primary neurons via NADPH oxidase-mediated activation of neutral sphingomyelinase: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(49):51451–51459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404635200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai J, Grutzendler J, Duff K, Gan WB. Fibrillar amyloid deposition leads to local synaptic abnormalities and breakage of neuronal branches. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7(11):1181–1183. doi: 10.1038/nn1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chromy BA, Nowak RJ, Lambert MP, et al. Self-assembly of Aβ1−42 into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2003;42(44):12749–12760. doi: 10.1021/bi030029q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demuro A, Mina E, Kayed R, Milton SC, Parker I, Glabe CG. Calcium dysregulation and membrane disruption as a ubiquitous neurotoxic mechanism of soluble amyloid oligomers. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(17):17294–17300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300(5618):486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoshi M, Sato M, Matsumoto S, et al. Spherical aggregates of β-amyloid (amylospheroid) show high neurotoxicity and activate tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(11):6370–6375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1237107100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barghorn S, Nimmrich V, Striebinger A, et al. Globular amyloid β-peptide1−42 oligomer—a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;95(3):834–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lesné S, Ming TK, Kotilinek L, et al. A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440(7082):352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416(6880):535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noguchi A, Matsumura S, Dezawa M, et al. Isolation and characterization of patient-derived, toxic, high mass amyloid β-protein (Aβ) assembly from Alzheimer disease brains. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(47):32895–32905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bateman DA, Chakrabartty A. Two distinct conformations of Aβ aggregates on the surface of living PC12 cells. Biophysical Journal. 2009;96(10):4260–4267. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engel MFM, Khemtémourian L, Kleijer CC, et al. Membrane damage by human islet amyloid polypeptide through fibril growth at the membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(16):6033–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708354105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto N, Matsubara E, Maeda S, et al. A ganglioside-induced toxic soluble Aβ assembly: its enhanced formation from Aβ bearing the arctic mutation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(4):2646–2655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuyama K, Yanagisawa K. Late endocytic dysfunction as a putative cause of amyloid fibril formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;109(5):1250–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Law A, Gauthier S, Quirion R. Say NO to Alzheimer’s disease: the putative links between nitric oxide and dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Brain Research Reviews. 2001;35(1):73–96. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Igbavboa U, Avdulov NA, Schroeder F, Wood WG. Increasing age alters transbilayer fluidity and cholesterol asymmetry in synaptic plasma membranes of mice. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;66(4):1717–1725. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66041717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi H, Igbavboa U, Hamanaka H, et al. Cholesterol is increased in the exofacial leaflet of synaptic plasma membranes of human apolipoprotein E4 knock-in mice. NeuroReport. 2002;13(4):383–386. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200203250-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto N, Matsubara T, Sato T, Yanagisawa K. Age-dependent high-density clustering of GM1 ganglioside at presynaptic neuritic terminals promotes amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1778(12):2717–2726. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Refolo LM, Pappolla MA, Malester B, et al. Hypercholesterolemia accelerates the Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiology of Disease. 2000;7(4):321–331. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolozin B. A fluid connection: colesterol and aβ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(10):5371–5373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101123198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marx J. Bad for the heart, bad for the mind? Science. 2001;294(5542):508–509. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5542.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gylys KH, Fein JA, Yang F, Miller CA, Cole GM. Increased cholesterol in Aβ-positive nerve terminals from Alzheimer’s disease cortex. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Molander-Melin M, Blennow K, Bogdanovic N, Dellheden B, Månsson JE, Fredman P. Structural membrane alterations in Alzheimer brains found to be associated with regional disease development; increased density of gangliosides GM1 and GM2 and loss of cholesterol in detergent-resistant membrane domains. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;92(1):171–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zinser EG, Hartmann T, Grimm MOW. Amyloid beta-protein and lipid metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1768(8):1991–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, et al. Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine. 1996;2(8):864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43) Neuron. 1994;13(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]