Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder (BPD) is characterized by altered intracellular calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis. Underlying mechanisms involve dysfunctions in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondrial Ca2+ handling, potentially mediated by B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), a key protein that regulates Ca2+ signaling by interacting directly with these organelles, and which has been implicated in the pathophysiology of BPD. Here, we examined the effects of the Bcl-2 gene single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs956572 on intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in patients with BPD.

Methods

Live cell fluorescence imaging and electron probe microanalysis were used to measure intracellular and intra-organelle free and total calcium in lymphoblasts from 18 subjects with BPD carrying the AA, AG, or GG variants of the rs956572 SNP. Analyses were carried out under basal conditions and in the presence of agents that affect Ca2+ dynamics.

Results

Compared with GG homozygotes, variant AA—which expresses significantly reduced Bcl-2 messenger RNA and protein—exhibited elevated basal cytosolic Ca2+ and larger increases in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor–mediated cytosolic Ca2+ elevations, the latter in parallel with enhanced depletion of the ER Ca2+ pool. The aberrant behavior of AA cells was reversed by chronic lithium treatment and mimicked in variant GG by a Bcl-2 inhibitor. In contrast, no differences between SNP variants were found in ER or mitochondrial total Ca2+ content or in basal store-operated Ca2+ entry.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that, in patients with BPD, abnormal Bcl-2 gene expression in the AA variant contributes to dysfunctional Ca2+ homeostasis through a specific ER inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor–dependent mechanism.

Keywords: Bcl-2, bipolar disorder, calcium, electron probe micro-analysis, endoplasmic reticulum, inositol 1;4;5-trisphosphate, mania, mitochondria

Impaired regulation of calcium (Ca2+) signaling is considered the most reproducible cellular abnormality in bipolar disorder (BPD) research(1), but the mechanisms underlying this abnormality remain poorly understood. Studies using peripheral cells from individuals with BPD have shown elevated Ca2+ levels, suggesting increased vulnerability to injury or impaired cellular resilience, broadly defined as the ability of cells to adapt to insults and maintain their original form and function (2,3). Furthermore, these abnormalities have been associated with dysfunction in both endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondrial activity (2,4,5).

The antiapoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) is a globally important signaling protein known to regulate diverse neurobiological processes such as neurogenesis (6), morphogenesis (7), and synaptic plasticity (8). Interestingly, behavioral studies (9) suggest that Bcl-2 plays a potential role in BPD, and mood stabilizers have been found to elevate Bcl-2 expression (10). A significant decrease in Bcl-2 protein and messenger RNA (mRNA) levels was recently described in the frontal cortex of individuals with BPD (11). In addition, a Bcl-2 gene single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs956572 variant AA) was shown to significantly reduce Bcl-2 levels and mRNA expression in human lymphoblasts and decrease grey matter volume in healthy subjects (12). Preclinical models have also demonstrated that 4 weeks of lithium treatment upregulates Bcl-2 in the dentate gyrus and hippocampus (13).

At the cellular level, Bcl-2 and its family members control Ca2+ dynamics through direct interaction with cytosolic targets, mitochondria, and/or the ER (14,15). On the ER, Bcl-2 is known to interact with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R), an ER Ca2+ channel that either elevates cytosolic Ca2+ directly by releasing intra-ER Ca2+, or indirectly by stimulating “capacitative” Ca2+ influx upon store depletion (16). Recent evidence suggests that Bcl-2 suppresses InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release; however, there are conflicting reports regarding the effect of Bcl-2 on luminal ER Ca2+ (reviewed in 17,18). This is a significant issue, because the basal state of ER Ca2+ stores might play an important role in cellular resilience, in that enhanced steady-state Ca2+ levels and continuous Ca2+ overload can increase cellular vulnerability to diverse stressors and apoptotic signals (19). Controversy notwithstanding, these observations support the idea that lowered Bcl-2 expression might be related to the dysfunctional Ca2+ regulation implicated in BPD (1). This hypothesis is further supported by the observation that chronic lithium treatment attenuates Ca2+ mobilization in lymphoblasts from individuals with BPD (20), an effect associated with inositol depletion (21) and Bcl-2 and ER chaperone up-regulation (22,23).

In this study, we examined the potential role of the functional Bcl-2 SNP on intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in human carriers of the A and G alleles in subjects with BPD.

Methods and Materials

Subjects and Samples

The potential functional role of the Bcl-2 SNP (rs956572) in cellular Ca2+ dynamics was studied in BPD patients who met Structured Interview for DSM-IV criteria (SCID-I) for BPD-I. Most of these individuals also had a first-degree relative with mood disorders (n = 9). Eighteen BPD-I subjects were included in this study, with equal numbers of individuals with variant AA (mean age 36.5 ±4.4 years), AG (age 41.8 ±5.4 years), and GG (age 35 ±7.8 years). An average of 20 cells/patient were analyzed/sample in each experiment. All experiments were carried out in duplicate. No significant differences among genotype were identified for age, gender, or family history of BPD. This study was approved by all local institutional review boards, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Cell Culture and Establishment of Immortalized Cell Lines

The Bcl-2 gene consists of one large intron; rs956572 is at the 3′ end. To understand the potential functional influence of rs956572, 72 human lymphoblast cell lines were genotyped. Of these, B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLCL) cultures from subjects carrying the Bcl-2 SNP rs956572 were selected to determine the influence of genotype on Bcl-2 levels and Ca2+ dynamics. The BLCL were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 media in a 5% carbon dioxide humidified atmosphere at 37°C; media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, antibiotics, and antimycotics. All samples were cultured under the same standard procedures. Cultures were split at a ratio of 1:5 every 3–5 days. To control for potential confounding effects of cell passage and culture conditions, all cell lines on the same passage were recovered together and cultured in media from the same bulk preparation. Media were changed at the same time for all lines 24 hours before cell harvest. Cells were collected by centrifugation at the same time and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline before being frozen and stored at −160°C. Propidium iodide staining was used to determine cell viability. All cultures presented more than 85% of viable cells.

Cells were thawed and used within 2 months. A previous study showed that the BLCL of the three different genotypes had no significant effects on Epstein-Barr Virus nuclear antigen induction (24).

Genotyping of rs956572

Genotyping was performed at Illumina (La Jolla, California), with Golden Gate Chemistry as part of a larger candidate-gene study. Genotypes displayed good clustering, Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium in parents (p >.5), perfect Mendelization (no Mendelian errors were detected in 318 parent-offspring trios), 99.3% completeness among 1288 genotyped samples, and 100% agreement among 24 blind duplicates. The genotyping assay was designed by Illumina on the basis of the following reference sequence: TAACCTCCCTGAGCCTAAATTTATGAATTCATAAAACAGAGAAAAATAAAAGGCTGTAGTTGTCGAGTGGTCAGGAGGATGAAATGACTTCTGTGAAGTGCCTGGCAGCAAAGGCACTAA[A/G]ATTCAGTCATGACTCCCTCTCATTCCTCTCTCATTTTTGCATTGAACTGTCAGAGATGGCAATTTTCCTTTCCTAGGTACCTTCTTTATTTACAAGTAGCTT.

The frequency of the minor (A) allele in the total sample was .42, which closely agrees with HapMap (.425–.442 in 120 CEU individuals).

Calcium Imaging and Analysis

Cells (1 ×106/mL) adhered to poly-L-lysine–treated 15-mm coverslips were pre-incubated for 45–60 min at 37°C in an extracellular buffer (ECB) [HBSS plus 20 mmol/L HEPES, .5% bovine serum albumin, and 1 mmol/L calcium dichloride] with 1 μmol/L acetoxymethyl esters of the fluorescent Ca2+ indicators fura-2 AM or fura-2FF (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). After incubation, cells were washed with ECB for 45 min at room temperature to permit dye de-esterification. Coverslips were mounted in a perfusion chamber on the stage of a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope equipped with a 40× Fluor objective (Zeiss, Thornwood, New York). Images and dual excitation (340/380 nm) fluorescence records were continuously acquired with EasyRatioPro hardware and software (PTI, Birmingham, New Jersey). Experiments were carried out at room temperature (22°–25°C) and ambient atmospheric conditions. Cells were randomly selected for each experiment. The 340/380 ratios were transformed to Ca2+ concentrations with established procedures (25).

Luminal ER Ca2+ measurements were performed according to Hofer (26) as adapted by Chen et al. (27). After incubation with 1 μmol/L fura-2FF AM and de-esterification as described, cells mounted on the inverted microscope were perfused with an intra-cellular buffer (intracellular buffer: 125 mmol/L potassium chloride, 25 mmol/L sodium chloride, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 200 μmol/L calcium dichloride, and 500 μmol/L ethylene glycol bis-(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N′-tetraacetic acid [EGTA], pH 7.25), supplemented with .5 mmol/L adenosine triphosphate. After selective permeabilization of plasma membrane with digitonin (10 μg/mL) for 40–60 sec, there was a strong decline in fluorescence excited at both 340 and 380 nm, but the residual signal had a higher 340/380-m ratio and reflected specific fluorescence from the ER lumen. After fluorescence reached steady-state, cells were perfused with the InsP3R agonist adenophostin A (AdA) (75 nmol/L) for 20–30 sec. A further abrupt drop in the 340/380 ratio denoting Ca2+ release from the ER was confirmed by manganese quench of fluorescence after InsP3R activation (27) (data not shown).

To estimate mitochondrial free Ca2+ levels, BLCL in ECB were loaded with dihydro-Rhod-2 (Invitrogen) for 60 min at 37°C. After being washed twice, cells were maintained at 37°C for an additional 60 min. Fluorescence (553/576 nm) was recorded with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss). After stabilizing the baseline, AdA (75 nmol/L) was added, and thereafter images were captured every 10 sec for 5 min. MitoTracker Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) was used to confirm mitochondrial localization. Average fluorescent intensity was determined, and F/F0 ratios were calculated before and after AdA treatment with Metamorph software (MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, California).

For the Bcl-2 inhibitor experiments, cells were incubated for 1 hour with BH3-I (100 μmol/L) in cell culture medium and then washed and incubated in Fura-2 AM as described in the preceding text. In the lithium experiments, cells were treated with lithium chloride (1 mmol/L) for 7 days.

Electron Probe Microanalysis

Samples of AA and GG BLCL were centrifuged to form a pellet that was placed on the tip of an aluminum pin and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane with a custom-designed freezing device. Pins were mounted in a Leica UC6 cryoultramicrotome precooled to −160°C, and ultrathin (approximately100-nm-thick) cryosections were prepared and mounted on electron microscopy supports. Specimens were cryo-transferred to an analytical cryo-electron microscope (Zeiss) and freeze-dried, and digital images were recorded by means of a ProScan 2 kb × 2 kb slow-scan charge-coupled device camera controlled by AnalySIS software (Soft Imaging Systems, Lakewood, Colorado). The x-ray spectra were recorded at ←110°C for 100 sec each with an approximately 5-nA focused probe with a diameter of 100 nm (mitochondria) or 63 nm (ER), as previously described (28). The x-ray spectra were recorded and processed with established procedures (29) to quantify total (i.e., free plus bound) elemental calcium concentrations. Concentrations are given in millimoles/kilogram dry weight.

Western Blotting and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

The BLCL were homogenized in an extraction buffer containing 20 mmol/L Tris-hydrogen chloride, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L sodium chloride, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mmol/L α-glycerophosphate, protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) and phosphatase inhibitor mixture I and II (Sigma). Homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 sec, total protein content was adjusted to the same level for all samples, and equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed on 10% or 4% to approximately 20% tris-glycine gels. The blots were blocked with 5% dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by incubation with a pan-IP3R antibody plus actin antibody (both Sigma, diluted 1:1000) or a Bcl-2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California) (diluted 1:500) plus the actin antibody in blocking buffer overnight. After four washes with Tris-buffered saline containing .05% Tween 20, the blots were incubated with an horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (diluted 1:2000; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, New Jersey) and then washed again four times. Finally, blots were developed with ECL (GE Healthcare) and visualized with Kodak x-ray film.

For qPCR of Bcl-2 mRNA, a PRISM 7900 Sequence detector system (ABI, Foster City, California) and the Platinum qPCR SuperMix-UDG w/ROX (Invitrogen) were used. Detection was performed in triplicate with a pretested optimized cycling program for primers.

Reagents

The AdA was obtained from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, New Jersey). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma. When dimethyl sulfoxide was used as a drug solvent, the final concentration in the recording medium did not exceed .1%.

Statistics

All experiments with human lymphoblasts were performed in duplicate. The average value/patient was used for statistical analysis, but similar results were obtained when data were analyzed according to the total number of cells/group, with higher significance than per-patient. Data were evaluated with Student t test (matched values, two-tailed, paired) for two groups or one-way analysis of variance plus Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. The χ2 test was used to test differences among genotypes in gender and family history. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to evaluate potential associations between Ca2+ levels and other numerical variables. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM; p values of < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

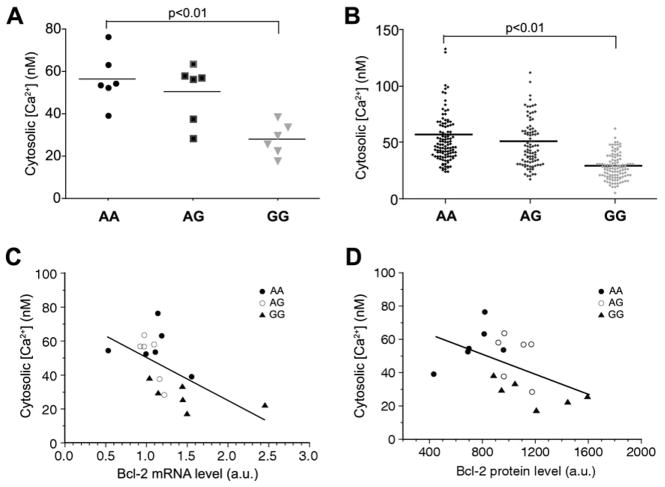

Basal Cytosolic Ca2+ Was Elevated in Lymphoblasts From BPD Subjects Carrying the Bcl-2–Deficient SNP Variant AA

We first evaluated the effects of the Bcl-2 SNP rs956572 on basal cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i). Figure 1A presents baseline cytosolic Ca2+ measurements on a per-patient basis for all BLCLs assayed, distributed according to the three patient groups (AA, AG, and GG) (ntotal = 18). A significant increase in [Ca2+]i was observed in the Bcl-2 SNP variant AA compared with the variant GG (AA = 56.6 ±5.1, AG =50.3 ±5.6, GG =27.9 ±3.1, F =10.1; AA vs. GG t = 4.27, p < .01). Results were similar when data were analyzed on an individual cell basis (Figure 1B). Furthermore, basal [Ca2+]i showed a significant inverse correlation with both Bcl-2 mRNA and protein levels (Figures 1C–1D) across the total sample. Interestingly, variant AA, which has the highest basal [Ca2+]i level, expressed the least Bcl-2.

Figure 1.

Basal cytosolic calcium in B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants. (A, B) Basal cytosolic free calcium (Ca2+) concentrations measured with fura-2 in B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLCL) from individual BPD patients (A) and in individual BLCL cells (B) from 18 patients of three genotypes incubated in extracellular medium containing 1.0 mmol/L Ca2+. Both patient/patient and cell/cell analysis indicated that [Ca2+]i in variant AA was significantly higher than in variant GG (p <.01). (C, D) Plot of the inverse correlations between individual patient-averaged cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and Bcl-2 messenger RNA expression (C) (r = .60, p <.01) and protein expression (D) (r =.49, p <.05) as a function of genotype. By both measures, reduced Bcl-2 expression in variant AA was associated with elevated basal [Ca2+]i. All statistical tests were one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni correction. a.u., arbitrary unit.

InsP3R Activation Selectively Enhanced Cytosolic Ca+2 Elevations in the Bcl-2 SNP Variant AA

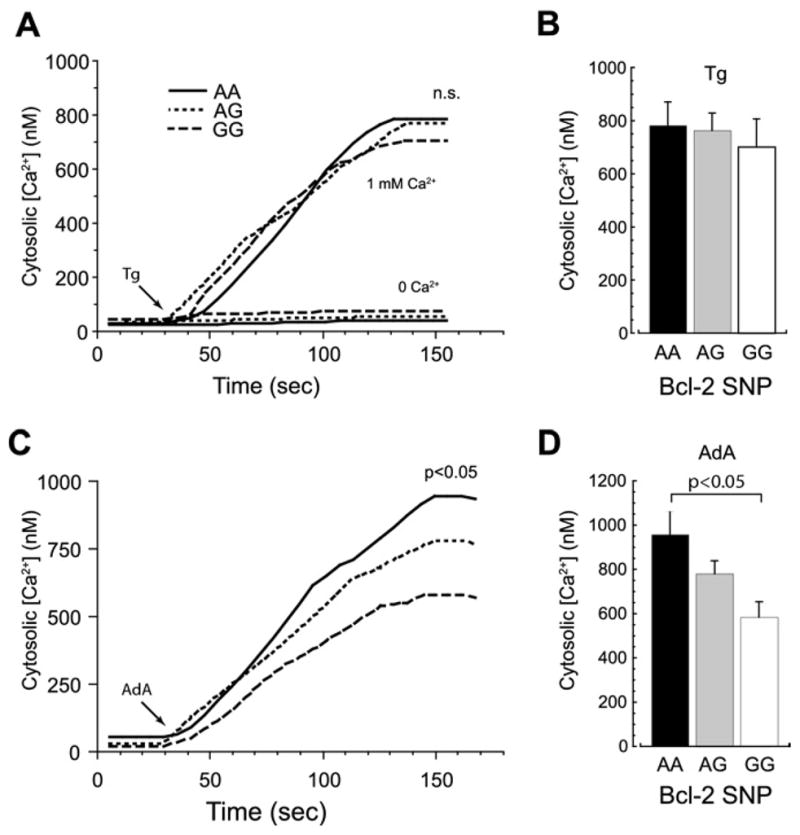

To evaluate the potential role of the ER and plasma membrane in the regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ changes associated with these Bcl-2 SNP variants, cells were treated with the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+–ATPase pump inhibitor thapsigargin (Tg) or with AdA, a selective InsP3R agonist. For all three SNP genotypes, Tg only minimally increased [Ca2+]i in Ca2+-free (EGTA-containing) medium (Figure 2A, lower traces) indicating that the mobilizable Ca2+ store was quite small in these cells; these results were further confirmed (Figure 3C). In contrast, Tg in the presence of 1 mmol/L external Ca2+ elicited robust but similar [Ca2+]i elevations in all three groups (AA =683 ±105; AG =757 ±66; GG =770 ±87; p = .79) (Figures 2A–2B). This implies that store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is a dominant component of Ca2+ regulation in this cell type (30), albeit one that is not directly impacted by the Bcl-2 SNP genotype.

Figure 2.

Cytosolic calcium dynamics in Bcl-2 SNP variants. (A) Representative cytosolic Ca2+ traces (fura-2) from BLCL of the three variants after stimulation with thapsigargin (Tg) (1 μmol/L) in Ca2+-free medium containing 200 μmol/L ethylene glycol bis-(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N′-tetraacetic acid (lower traces) or medium containing 1 mmol/L extracellular Ca2+ (upper traces). Tg induced significant [Ca2+]i elevations only in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. (B) Average (per-patient) [Ca2+]i elevations in BLCL of the three different genotypes after Tg incubation in Ca2+-containing medium did not significantly differ. (C, D) Typical Ca2+ traces (C) and average [Ca2+]i elevations (D) in cells from the three Bcl-2 SNP variants after exposure to the InsP3R agonist adenophostin A (AdA) (75 nmol/L) in a medium containing 1 mmol/L extracellular Ca2+ revealed a graded, genotype-dependent response. The [Ca2+]i elevations in variant AA were significantly higher than in variant GG (p < .05). Other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

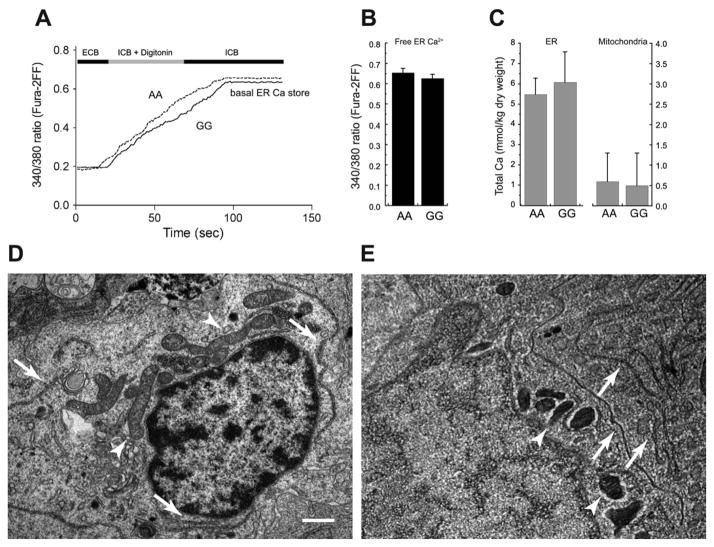

Basal endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondrial Ca2+ stores are not altered in cells expressing the Bcl-2 SNP variant AA. (A, B) Typical Ca2+ traces (A) and per-patient averages (B) of low-affinity fura-2FF fluorescence emission (ratio 340/380 nm) from AA and GG BLCL permeabilized with digitonin (10 μg/mL) in an intracellular buffer (ICB) supplemented with 500 μmol/L adenosine triphosphate. Fluorescence gradually increased to a steady-state maximum that reflects the level of luminal ER Ca2+(23). Basal ER free Ca2+ was similar in Bcl-2 SNP variants AA and GG. (C) Total ER and mitochondrial matrix calcium concentrations, as measured by electron probe microanalysis, were similar in variants AA and GG, although the former was tenfold higher. (D, E) Electron micrographs of BLCL perinuclear regions. Left panel is a conventionally fixed and embedded specimen; right panel is a rapidly frozen, cryosectioned, and freeze-dried preparation as used for electron probe microanalysis. Both panels illustrate typical organelle abundance and distribution, including ER (arrows) and mitochondria (arrowheads). Bar = .5 μm for both panels. ECB, extracellular buffer; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Similar to Tg, direct InsP3R activation with AdA in a zero-Ca2+ medium induced only negligible [Ca2+]i elevations, which were indistinguishable between genotypes (data not shown). In normal Ca2+ (1 mmol/L) medium, however, a significantly larger, presumably SOCE-mediated, increase in [Ca2+]i in variant AA was observed compared with variant GG (AA =958 ±108, AG =781 ±58, GG = 585 ± 70, F = 5.03; AA vs. GG t = 3.17, p < .05 after Bonferroni correction) (Figures 2C–2D). These observations suggest that the Bcl-2 gene SNP variant AA might exert its effect by specifically modulating ER InsP3Rs.

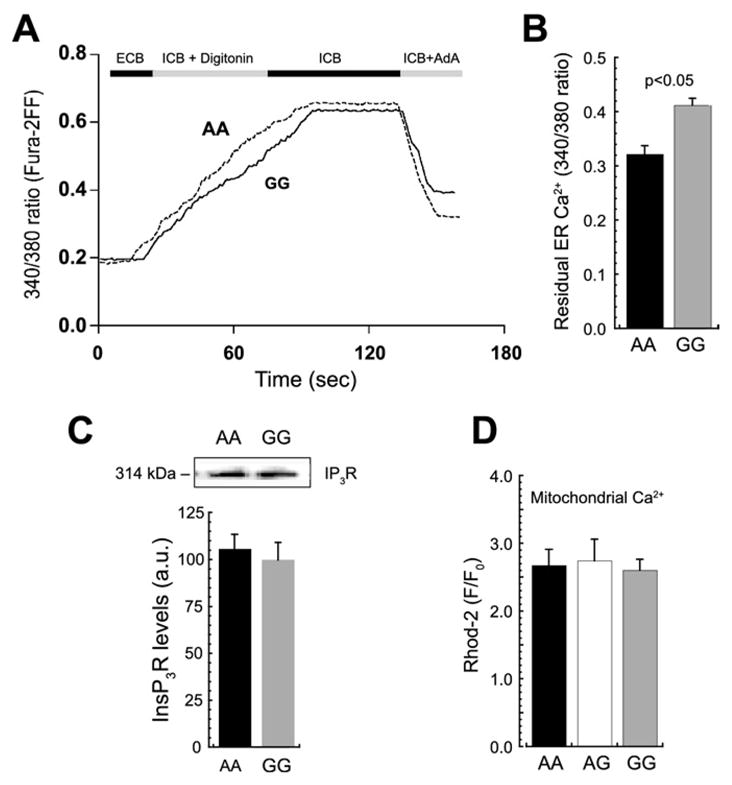

InsP3-Mediated ER Ca2+ Release But Not Basal ER or Mitochondrial Ca2+ Was Increased in the Bcl-2 SNP Variant AA

Given that InsP3R activation induced dissimilar [Ca2+]i elevations in different Bcl-2 SNP variants, InsP3R-mediated ER Ca2+ regulation was studied in greater detail. Free and total basal ER luminal Ca2+ concentrations were evaluated directly by means of fluorescence microscopy and electron probe microanalysis, respectively. With a technique that selectively loads Ca2+-sensitive dye into the ER lumen of permeabilized cells (26), we found no difference in basal free ER Ca2+ between variants AA and GG (low-affinity fura-2FF, 340/380 ratios .65 ± .22 vs. .62 ± .23, ns) (Figures 3A–3B). Similarly, no significant difference in total ER luminal Ca2+(AA =5.5 ± .8, GG = 6.1 ± 1.5 mmol/kg dry weight) was observed (Figures 3C–3E). The low concentrations found here further suggest the small size of the basal ER calcium store. Because mitochondria generally play a significant role in Ca2+ regulation, we used electron probe microanalysis to assess the status of resting mitochondrial Ca2+ and found that total Ca2+ pools were small and similar in all SNP variants (Figures 3C–3E).

To determine the extent of ER Ca2+ release after InsP3R activation, we used the permeabilization and ER loading strategy outlined in Figure 3A to directly measure the relative size of the luminal free Ca2+ pool after AdA exposure. A significant decrease was observed in the 340/380 fluorescence ratio in variant AA relative to variant GG (p < .05) (Figures 4A–4B), which implies reduced residual ER Ca2+ content and therefore increased luminal Ca2+ loss in SNP variant AA. Because no difference was observed in InsP3R expression between Bcl-2 SNP variants as determined with load-normalized gels and a pan-reactive IP3R antibody (Figure 4C), the most straightforward explanation for increased Ca2+ release from the ER pool of Bcl-2–deficient lymphoblasts is a quantitative reduction in the molecular interaction of Bcl-2 with InsP3Rs (27,31). The InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ rise was accompanied by an approximately threefold increase in free mitochondrial matrix Ca2+, as reported by rhod-2 fluorescence, but the three SNP variants did not differ significantly with respect to mean F/F0 (AA, 2.68 ± .23; AG, 2.74 ±.31; GG, 2.603 ± .16; ns) (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3)-induced ER Ca2+ release is enhanced in Bcl-2 SNP variant AA. (A, B) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R)–dependent reduction in ER Ca2+ directly measured with fura-2FF in permeabilized cells. Traces in panel A are a continuation of Figure 3A, with the InsP3 agonist AdA (75 nmol/L) added after a steady-state fluorescence ratio was reached; the sharp decline in fluorescence after AdA application corresponds to the decrease of ER luminal free Ca2+. Per-patient averages of residual ER Ca2+ after AdA (B) showed significantly greater Ca2+ release in the variant AA compared with GG (p < .05). (C) Representative Western blots and quantitative estimation of InsP3R total protein show no differences between AA and GG cells. (D) Similarly, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, measured with the Ca2+-selective dye Rhod-2, detected no differences among the three variants after AdA application (p = .77). Other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 3.

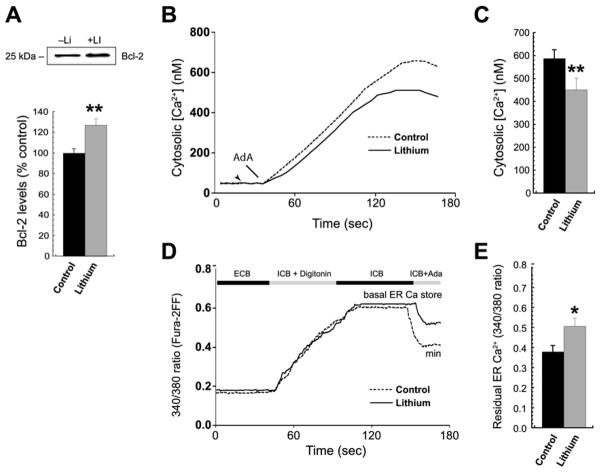

Lithium Reduced Abnormally High IP3-Dependent ER Ca2+ Release in BPD Subjects Carrying the AA Variant

Treatment with lithium (1 mmol/L for 7 days) significantly increased Bcl-2 levels (to 128% of control, p < .01) in BLCL from BPD subjects expressing variant AA (Figure 5A). Lithium-treated AA cells showed a trend toward decreased basal cytosolic Ca2+ levels that did not, however, reach significance (untreated, 52.2 ±7.9 nmol/L; lithium-treated, 37.3 ± 7.0 nmol/L; t = 2.39, p = .07). We also examined the effects of lithium on cytosolic and ER Ca2+ after stimulation in the functional Bcl-2 SNP. Lithium significantly decreased the abnormally high InsP3-induced cytosolic Ca2+ elevations in the Bcl-2 SNP (rs956572) AA relative to untreated cells (451 ± 51 nmol/L with lithium vs. 588 ± 38 nmol/L in control subjects, t = 2.82; p < .05) (Figures 5B–5C); this suggests a rescue effect on Ca2+ dysregulation for this Bcl-2 SNP allele.

Figure 5.

Lithium reduces InsP3R-dependent ER Ca2+ release in Bcl-2 SNP variant AA. (A) Representative Western blots (top) and per-patient averages (duplicate analysis, n = 6 each) showed a significant increase in Bcl-2 expression in lithium-treated (1 mmol/L for 7 days) AA BLCL relative to untreated cells (**p < .01). (B, C) Representative cytosolic Ca2+ traces (fura-2) and per-patient averages showed reduced AdA-stimulated (75 nmol/L) [Ca2+]i elevations in lithium-treated lymphoblasts (**p <.01). (D, E) In an experiment analogous to Figure 4A, typical traces of fura-2FF fluorescence emission (340/380 nm ratio, panel D) and per-patient averages (E) from digitonin-permeabilized, ER loaded cells showed reduced AdA-induced ER Ca2+ release in lithium-treated AA lymphoblasts (*p < .05). Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 3.

To determine whether lithium treatment affected basal and/or releasable luminal ER Ca2+ in an InsP3- and Bcl-2-dependent manner, ER luminal Ca2+ was estimated before and after AdA exposure. Lithium did not significantly alter basal ER Ca2+ levels in variant AA (340/380 fluorescence ratios (.59 ±.11 lithium-treated vs. .51 ±.18 untreated; t = 1.45, p = .2) (Figure 5D) but did reduce the abnormally large loss of luminal ER Ca2+ after InsP3R activation in variant AA compared with untreated cells (340/380 ratios .47 ±.10 lithium-treated vs. .38 ± .07 control subjects; t = 3.14, p = .02) (Figure 5D–5E).

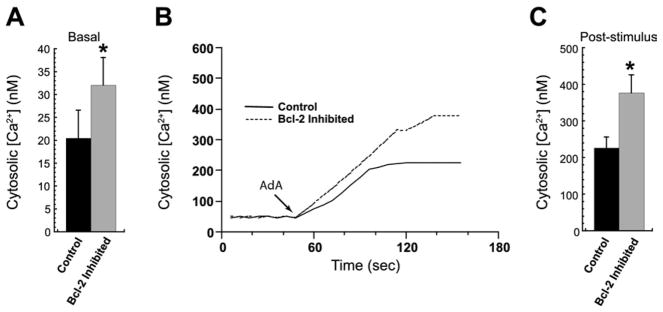

Bcl-2 Inhibition Elevated Basal and InsP3R-Stimulated Cytosolic Calcium in the Variant GG

To confirm the role of Bcl-2 in facilitating InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ dysregulation in the Bcl-2 SNP, variant GG lymphoblasts were pre-incubated with BH3-I, a Bcl-2 inhibitor (32), for 1 hour before fura-2 loading. The Bcl-2 downregulation significantly increased baseline [Ca2+]i compared with control GG cells (32.1 ± 6.0 nmol/L vs. 20.5 ± 6.2 nmol/L, respectively; p <.05) (Figure 6A). Likewise, a significant increase in InsP3R agonist-stimulated [Ca2+]i elevations was observed after incubation (377.1 ± 49.1 nmol/L with inhibitor vs. 226.9 ± 29.9 nmol/L without; p < .05) (Figures 6B–6C). Thus, Bcl-2 inhibition seemed to transform the GG variant so that Ca2+ regulation in this genotype resembled that observed in the Bcl-2-deficient variant AA.

Figure 6.

The Bcl-2 inhibition elevates InsP3R-dependent cytosolic Ca2+ in the SNP variant GG. (A) One-hour pre-incubation with the Bcl-2 inhibitor BH3-I significantly increased fura-2-measured basal [Ca2 +]i in BLCL from the variant GG (*p < .05 relative to control). (B, C) Representative cytosolic Ca2+ traces (B) and per-patient averages (C) show enhanced AdA-stimulated (75 nmol/L) [Ca2+]i elevation in GG lymphoblasts after Bcl-2 inhibition (*p < .05). Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 3.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that Bcl-2 gene expression regulated by the rs956572 SNP directly impacted intracellular Ca2+ dysregulation in individuals with BPD. Specifically, we found a selective and integrated control by Bcl-2 of both cytosolic Ca2+ levels and the InsP3R-dependent releasable ER Ca2+ pool in A carriers, thus marking the ER as the main functional target of this Bcl-2–deficient variant in subjects with BPD. In variant AA, this control was reflected by increased baseline and InsP3R agonist-stimulated cytosolic Ca2+ levels, in parallel with enhanced reduction of luminal ER Ca2+ after stimulation. The lower Bcl-2 levels present in the AA variant did not affect basal ER or mitochondrial Ca2+ content; nor did they modulate stimulated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. In addition, chronic lithium treatment reversed the abnormally high InsP3R-dependent ER Ca2+ release and cytosolic Ca2+ elevations associated with the untreated A carriers. Basal ER Ca2+ content was unchanged after lithium treatment. Finally, pharmacological downregulation of Bcl-2 in the nondeficient Bcl-2 SNP variant GG increased basal and InsP3R-dependent cytosolic Ca2+ levels, so that Ca2+ regulation in this variant resembled that observed in variant AA.

A recent study demonstrated that the lower Bcl-2 levels associated with the Bcl-2–deficient allele AA directly affects the brain by significantly reducing grey matter volume in the ventral striatum of healthy subjects (12). This area is known to play a critical role in the neurobiology and pathophysiology of mood disorders, for example in reward processing and emotion regulation (33). Thus, the increased Bcl-2-modulated, ER-mediated cytosolic Ca2+ levels observed in the present investigation might be intrinsically associated with both increased risk for apoptosis (34) and decreased grey matter volume (12) in subjects carrying the AA allele. To our knowledge, this study is the first to directly and comprehensively quantify intracellular Ca2+ levels in the context of Ca2+ regulation by a BPD-related gene polymorphism.

Several lines of evidence support the involvement of ER stress proteins such as GRP78 and calreticulin in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of BPD (2). Mechanisms might well involve Bcl-2 modulation of InsP3R-dependent ER Ca2+ release, because enhanced expression of GRP78 and calreticulin is regulated by Bcl-2 (14). As noted previously, the role of Bcl-2 in ER and cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics has received increasing attention in recent years, with conflicting results. Several studies have shown that Bcl-2 inhibits Ca2+ release from the ER and preserves ER luminal Ca2+, whereas other reports suggest that Bcl-2 increases Ca2+ leak across ER membranes, thus decreasing luminal Ca2+ levels (17,18). Considering that we found no difference in InsP3R expression levels among SNP variants, the present results are consistent with studies indicating that direct Bcl-2/InsP3R interactions reduce the permeability of this ER Ca2+ channel, thereby attenuating baseline cytosolic Ca2+ levels (27,31). Presumably, these same interactions facilitate the store depletion-mediated SOCE that accounts for regulatory Ca2+ elevations in BLCL. It remains to be determined whether the molecular mechanism(s) of SOCE in BLCL involves the stromal interaction molecule/Orai pathway, STIM/transient receptor potential (TRP) channel interactions (canonical TRPC3-like channels) are known to be present in this cell type) (30), both, or perhaps other pathways. Ultimately, it will be important to clarify the mechanisms associated with InsP3R sensitization in Ca2+ dysregulation, particularly because Ca2+ dysregulation seems to be an underlying characteristic of other disorders in addition to BPD (for instance, Alzheimer’s disease) (35,36). It is also important to note that although mitochondria play a major role in Ca2+ regulation (37)—including in immune cells (38)—and that several studies support a role for mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathophysiology of BPD (39), the present study found no significant differences in either free or total mitochondrial Ca2+ at rest or after InsP3R activation in any Bcl-2 SNP variant.

Previous studies have demonstrated that lithium increases Bcl-2 levels in several brain areas, and these effects are thought to underlie lithium’s therapeutic mechanisms (40). Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces the formation of reactive oxygen species in part by upregulating Ca2+ signaling. Interestingly, an inverse correlation between Bcl-2 and reactive oxygen species levels was described in the lymphocytes of individuals with BPD (41), and altered Bcl-2 levels and increased oxidative stress have both been observed in BPD subjects, with rescue effects seen after lithium treatment (42,43). Given that the integrity of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis is critical to cell survival, the effect of lithium on Ca2+ signaling might be mechanistically relevant to its neuroprotective actions, now thought to be key to the clinical effects of this agent (40).

Several technical aspects of this study merit comment, including the multiple advantages of using cultured lymphoblasts. These cells are easily accessible and manifest biological responses similar to central nervous system neurons (1). Furthermore, they are suitable for pharmacological studies both in vivo and in vitro, and the several passages necessary for culture limit the potential bias of environmental factors. Lastly, Epstein-Barr Virus transformation does not significantly alter the expression of key proteins (1). Most studies evaluating InsP3-dependent Bcl-2 regulation of ER Ca2+ release have been performed in cells overexpressing Bcl-2. A strength of the present investigation is that changes in Bcl-2 levels were endogenously expressed by a potential functional polymorphism without any pharmacological or biological intervention aimed at regulating Bcl-2 levels; this is particularly important, because transient Bcl-2 overexpression might be toxic (44,45). In addition, this study is the first to quantitatively measure cytosolic and intra-organelle Ca2+ levels on an individual, cell-by-cell basis, which was possible because of the inherent advantages of microscopy-based techniques. Microscopy approaches have other advantages relative to methods that provide only population averages; for example, microscopy allows the exclusion of nonviable cells, the characterization of cell-to-cell variability, and the direct measurement of organelle Ca2+ levels under various experimental conditions.

It must be acknowledged that it is presently unclear how— or even whether—the SNP variants studied here relate to an increased risk for developing BPD. The results obtained regarding the AA variant provide evidence for Ca2+ dysregulation, which might be a candidate for a risk allele; however, similar genotype-specific Ca2+ dysregulation has been reported by others for the GG variant (46), implying that the rs956572 polymorphism is not causal. Thus, we do not consider the present effects to be specific to BPD. Although it is plausible that this Bcl-2 SNP plays some role in the pathophysiology of BPD, it remains unclear how such an intronic variant might operate to functionally influence Bcl-2 transcription and/or expression. Nevertheless, the evidence presented demonstrates that this SNP variant critically affects intracellular Ca2+ signaling in BLCL from BPD subjects by altering the “gain” of InsP3R-dependent ER Ca2+ release. The results might provide new insights into the potential functional role of Bcl-2 in physiological and pathophysiological states.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Data and biomaterials were collected in four projects that participated in the NIMH Bipolar Disorder Genetics Initiative. From 1991 to 1998, the Principal Investigators and Co-Investigators were: Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana, U01 MH46282, John Nurnberger, M.D., Ph.D., Marvin Miller, M.D., and Elizabeth Bowman, M.D.; Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, U01 MH46280, Theodore Reich, M.D., Allison Goate, Ph.D., and John Rice, Ph.D.; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland U01 MH46274, J. Raymond DePaulo, Jr., M.D., Sylvia Simpson, M.D., MPH, and Colin Stine, Ph.D.; NIMH Intramural Research Program, Clinical Neurogenetics Branch, Bethesda, Maryland, Elliot Gershon, M.D., Diane Kazuba, B.A., and Elizabeth Maxwell, M.S.W.

Data and biomaterials were collected as part of ten projects that participated in the NIMH Bipolar Disorder Genetics Initiative. From 1999 to 2003, the Principal Investigators and Co-Investigators were: Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana, R01 MH59545, John Nurnberger, M.D., Ph.D., Marvin J. Miller, M.D., Elizabeth S. Bowman, M.D., N. Leela Rau, M.D., P. Ryan Moe, M.D., Nalini Samavedy, M.D., Rif El-Mallakh, M.D. (at University of Louisville), Debra A. Glitz, M.D. (at Wayne State University), Eric T. Meyer, M.S., Carrie Smiley, R.N., Tatiana Foroud, Ph.D., Leah Flury, M.S., Danielle M. Dick, Ph.D., Howard Edenberg, Ph.D.; Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, R01 MH059534, John Rice, Ph.D, Theodore Reich, M.D., Allison Goate, Ph.D., Laura Bierut, M.D.; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, R01 MH59533, Melvin McInnis M.D., J. Raymond DePaulo Jr., M.D., Dean F. MacKinnon, M.D., Francis M. Mondimore, M.D., James B. Potash, M.D., Peter P. Zandi, Ph.D, Dimitrios Avramopoulos, and Jennifer Payne; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, R01 MH59553, Wade Berrettini M.D., Ph.D.; University of California at Irvine, Irvine, California, R01 MH60068, William Byerley M.D., and Mark Vawter M.D.; University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, R01 MH059548, William Coryell M.D., and Raymond Crowe M.D.; University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, R01 MH59535, Elliot Gershon, M.D., Judith Badner Ph.D., Francis McMahon M.D., Chunyu Liu Ph.D., Alan Sanders M.D., Maria Caserta, Steven Dinwiddie M.D., Tu Nguyen, Donna Harakal; University of California at San Diego, San Diego, California, R01 MH59567, John Kelsoe, M.D., Rebecca McKinney, B.A.; Rush University, Chicago, Illinois, R01 MH059556, William Scheftner M.D., Howard M. Kravitz, D.O., M.P.H., Diana Marta, B.S., Annette Vaughn-Brown, MSN, RN, and Laurie Bederow, MA; NIMH Intramural Research Program, Bethesda, Maryland, 1Z01MH002810-01, Francis J. McMahon, M.D., Layla Kassem, PsyD, Sevilla Detera-Wadleigh, Ph.D, Lisa Austin, Ph.D, Dennis L. Murphy, M.D. In addition, families were contributed by Dr. Carlos Pato and his staff at the University of Southern California.

This work was sponsored by NIMH Grants MH52618 and MH058693. Genotyping services were provided by the Center for Inherited Disease Research. The Center for Inherited Disease Research is fully funded through a federal contract from the NIH to The Johns Hopkins University, Contract Number N01-HG-65403. Data and biomaterials were collected and supported by NIMH Grant R01 MH59602 (to Miron Baron, M.D.) and by funds from the Columbia Genome Center and the New York State Office of Mental Health. The main contributors to this work were Miron Baron, M.D. (Principal Investigator), Jean Endicott, Ph.D. (Co-Principal Investigator), Jo Ellen Loth, M.S.W., John Nee, Ph.D, Richard Blumenthal, Ph.D., Lawrence Sharpe, M.D., Barbara Lilliston, M.S.W., Melissa Smith, M.A., and Kristine Trautman, M.S.W., all from the Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, New York, New York. A small subset of the sample was collected in Israel in collaboration with Bernard Lerer, M.D., and Kyra Kanyas, M.S., from the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

We are grateful to the patients and their families for their cooperation and support and to the treatment facilities and other organizations that collaborated with us in identifying families. Statistical advice was provided by David Luckenbaugh (NIMH). We also thank Ioline Henter (NIMH) for her outstanding editorial assistance.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Dr. Manji is now Global Therapeutic Area Head, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, and a full time employee of Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Zarate is listed as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of ketamine in major depression. Dr. Zarate has assigned his patent rights on ketamine to the US Government. All authors declare that, except for income received from our primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past 3 years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Warsh JJ, Andreopoulos S, Li PP. Role of intracellular calcium signaling in the pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder: Current status. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2004;4:201–213. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato T. Molecular neurobiology of bipolar disorder: A disease of ’mood-stabilizing neurons’? Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manji HK, Quiroz JA, Payne JL, Singh J, Lopes BP, Viegas JS, et al. The underlying neurobiology of bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry. 2003;2:136–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashi A, Kasahara T, Kametani M, Toyota T, Yoshikawa T, Kato T. Aberrant endoplasmic reticulum stress response in lymphoblastoid cells from patients with bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:33–43. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quiroz JA, Gray NA, Kato T, Manji HK. Mitochondrially mediated plasticity in the pathophysiology and treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2551–2565. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn HG, Biebl M, Wilhelm D, Li M, Friedlander RM, Winkler J. Increased generation of granule cells in adult Bcl-2-overexpressing mice: A role for cell death during continued hippocampal neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1907–1915. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen DF, Schneider GE, Martinou JC, Tonegawa S. Bcl-2 promotes regeneration of severed axons in mammalian CNS. Nature. 1997;385:434–439. doi: 10.1038/385434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattson MP. Calcium and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell. 2007;6:337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lien R, Flaisher-Grinberg S, Cleary C, Hejny M, Einat H. Behavioral effects of Bcl-2 deficiency: Implications for affective disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60:490–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manji HK, Moore GJ, Chen G. Lithium up-regulates the cytoprotective protein Bcl-2 in the CNS in vivo: A role for neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects in manic depressive illness. 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HW, Rappoport SI, Rao JS. Altered expression of apoptotic factors and synaptic markers in postmortem brain from bipolar disorder patients. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvadore G, Nugent AC, Chen G, Akula N, Yuan P, Cannon DM, et al. Bcl-2 polymorphism influences gray matter volume in the ventral striatum in healthy humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:804–807. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammonds MD, Shim SS. Effects of 4-week treatment with lithium and olanzapine on levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, B-Cell CLL/Lymphoma 2 and phosphorylated cyclic adenosine mono-phosphate response element-binding protein in the sub-regions of the hippocampus. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;105:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Distelhorst CW, Shore GC. Bcl-2 and calcium: Controversy beneath the surface. Oncogene. 2004;23:2875–2880. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetz CA. ER stress signaling and the BCL-2 family of proteins: From adaptation to irreversible cellular damage. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2345–2355. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berridge MJ. The endoplasmic reticulum: A multifunctional signaling organelle. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinton P, Rizzuto R. Bcl-2 and Ca2+ homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1409–1418. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rong Y, Distelhorst CW. Bcl-2 protein family members: Versatile regulators of calcium signaling in cell survival and apoptosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.021507.105852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szabadkai G, Rizzuto R. Participation of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial calcium handling in apoptosis: More than just neighborhood? FEBS Lett. 2004;567:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasserman MJ, Corson TW, Sibony D, Cooke RG, Parikh SV, Pennefather PS, et al. Chronic lithium treatment attenuates intracellular calcium mobilization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:759–769. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams RS, Cheng L, Mudge AW, Harwood AJ. A common mechanism of action for three mood-stabilizing drugs. Nature. 2002;417:292–295. doi: 10.1038/417292a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen B, Wang JF, Young LT. Chronic valproate treatment increases expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins in the rat cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:658–664. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen G, Zeng WZ, Yuan PX, Huang LD, Jiang YM, Zhao ZH, et al. The mood-stabilizing agents lithium and valproate robustly increase the levels of the neuroprotective protein bcl-2 in the CNS. J Neurochem. 1999;72:879–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.720879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manji HK. Bcl-2: A key regulator of affective resilience in the pathophysiology and treatment of severe mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(Suppl 1):243S. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofer AM. Measurement of free [Ca2+] changes in agonist-sensitive internal stores using compartmentalized fluorescent indicators. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;114:249–265. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-250-3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen R, Valencia I, Zhong F, McColl KS, Roderick HL, Bootman MD, et al. Bcl-2 functionally interacts with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors to regulate calcium release from the ER in response to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:193–203. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hongpaisan J, Pivovarova NB, Colegrove SL, Leapman RD, Friel DD, Andrews SB. Multiple modes of calcium-induced calcium release in sympathetic neurons II: a [Ca2+]i- and location-dependent transition from endoplasmic reticulum Ca accumulation to net Ca release. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:101–112. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pivovarova NB, Hongpaisan J, Andrews SB, Friel DD. Depolarization-induced mitochondrial Ca accumulation in sympathetic neurons: Spatial and temporal characteristics. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6372–6384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06372.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perova T, Wasserman MJ, Li PP, Warsh JJ. Hyperactive intracellular calcium dynamics in B lymphoblasts from patients with bipolar I disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharm. 2007;11:185–196. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanson CJ, Bootman MD, Distelhorst CW, Wojcikiewicz RJ, Roderick HL. Bcl-2 suppresses Ca2+ release through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and inhibits Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria without affecting ER calcium store content. Cell Calcium. 2008;44:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogler M, Dinsdale D, Dyer MJ, Cohen GM. Bcl-2 inhibitors: small molecules with a big impact on cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:360–367. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan P, Baum AE, Zhou R, Wang Y, Laje G, McMahon FJ, et al. Bcl-2 polymorphisms associated with mood disorders and antidepressant responsiveness regulate Bcl-2 gene expression and cellular resilience in human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(suppl 1):63S. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheung KH, Shineman D, Muller M, Cardenas C, Mei L, Yang J, et al. Mechanism of Ca2+ disruption in Alzheimer’s disease by presenilin regulation of InsP3 receptor channel gating. Neuron. 2008;58:871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tu H, Nelson O, Bezprozvanny A, Wang Z, Lee SF, Hao YH, et al. Presenilins form ER Ca2+ leak channels, a function disrupted by familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked mutations. Cell. 2006;126:981–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giorgi C, Romagnoli A, Pinton P, Rizzuto R. Ca2+ signaling, mitochondria and cell death. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:119–130. doi: 10.2174/156652408783769571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis RS. Calcium signaling mechanisms in T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:497–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato T, Kato N. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:180–190. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manji HK, Moore GJ, Chen G. Lithium up-regulates the cytoprotective protein Bcl-2 in the CNS in vivo: A role for neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects in manic depressive illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 9):82–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hildeman DA, Mitchell T, Aronow B, Wojciechowski S, Kappler J, Marrack P. Control of Bcl-2 expression by reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15035–15040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936213100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Machado-Vieira R, Andreazza AC, Viale CI, Zanatto V, Cereser V, Jr, da Silva Vargas R, et al. Oxidative stress parameters in unmedicated and treated bipolar subjects during initial manic episode: A possible role for lithium antioxidant effects. Neurosci Lett. 2007;421:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ng F, Berk M, Dean O, Bush AI. Oxidative stress in psychiatric disorders: Evidence base and therapeutic implications. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:851–876. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uhlmann EJ, Subramanian T, Vater CA, Lutz R, Chinnadurai G. A potent cell death activity associated with transient high level expression of BCL-2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17926–17932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang NS, Unkila MT, Reineks EZ, Distelhorst CW. Transient expression of wild-type or mitochondrially targeted Bcl-2 induces apoptosis, whereas transient expression of endoplasmic reticulum-targeted Bcl-2 is protective against Bax-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44117–44128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uemura T, Warsh J, Li PP, Green M, Cui C, Corson T, Perova T. Bcl-2 polymorphism rs956572 modifies disrupted Ca2+ homeostasis in Bipolar Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(suppl 1):240S. [Google Scholar]