Abstract

Modifying the energy content of foods, particularly foods eaten away from home, is important in addressing the obesity epidemic. Chefs in the restaurant industry are uniquely placed to influence the provision of reduced-calorie foods, but little is known about their opinions on this issue. A survey was conducted among chefs attending U.S. culinary meetings about strategies for creating reduced-calorie foods and opportunities for introducing such items on restaurant menus. The 432 respondents were from a wide variety of employment positions and the majority had been in the restaurant industry for 20 years or more. Nearly all chefs (93%) thought that the calories in menu items could be reduced by 10 to 25% without customers noticing. To decrease the calories in two specific foods, respondents were more likely to select strategies for reducing energy density than for reducing portion size (p<0.004). Low consumer demand was identified as the greatest barrier to including reduced-calorie items on the menu by 38% of chefs, followed by the need for staff skills and training (24%), and high ingredient cost (18%). The majority of respondents (71%) ranked taste as the most influential factor in the success of reduced-calorie items (p<0.0001). The results of this survey indicate that opportunities exist for reducing the energy content of restaurant items. Ongoing collaboration is needed between chefs and public health professionals to ensure that appealing reduced-calorie menu items are more widely available in restaurants and that research is directed towards effective ways to develop and promote these items.

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing recognition that an essential part of addressing the obesity epidemic is modifications to the eating environment, particularly those that support the consumption of appropriate amounts of energy (1, 2). A major component of the eating environment is food eaten away from home, which has increased in frequency over recent decades (3) and now accounts for about half of all food expenditure in the US (4). Chefs in the restaurant industry have unique opportunities to influence eating behavior by ensuring that consumers have reduced-calorie options available when eating out. In order to support this objective, however, it is important to address the concerns of chefs about providing such foods. The present study examines the opinions of chefs about strategies for creating reduced-calorie foods and opportunities for including such items on restaurant menus.

The role of foods eaten away from home in the prevention of obesity was examined by a forum convened in 2005 by the Keystone Center, a non-profit public policy organization, at the request of the U. S. Food and Drug Administration. The final report recommended a shift towards intake appropriate to individual energy needs as well as increasing consumption of foods lower in calorie density. The report contained seven recommendations for influencing consumer behavior, including 1) increasing the marketing of lower-calorie and less-calorie-dense foods while reducing the marketing of large portions of higher-calorie-dense foods, 2) updating standards for foods marketed to children, 3) promoting low-calorie-dense food patterns, 4) promoting “healthy lifestyle” education programs, 5) reviewing the effectiveness of existing programs on these topics, 6) improving government access to data regarding consumer behavior, and 7) ensuring that relevant information is publically available. (5). A particular focus of the report was promoting the wider inclusion of menu choices that are reduced in energy density (calories per weight), and a recommendation was made to conduct a scientific survey to gather information from chefs and restaurant owners about their experiences in developing menu items that could help customers to achieve and maintain a healthy weight.

We previously conducted a survey of 300 chefs regarding their knowledge and opinions of the portion sizes of restaurant foods and the influence on customer intake (6). The present research was designed to extend the previous survey by expanding the focus to various strategies for reducing the calorie content of foods served in restaurants. A particular interest was chefs’ opinions about modifications in food energy density, since this approach has shown promise for moderating energy intake in controlled feeding studies (7), and was emphasized in the report of the Keystone Forum. The objectives of the present study were to determine the opinions of chefs about strategies for creating reduced-calorie foods, about issues and barriers related to providing these items on the menu, and about the influence of the calorie content of restaurant items on customer intake.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Survey development

The questions included in the survey were based on a small pilot survey conducted as part of the Keystone Forum report (5) and on the previous survey of chefs about portion sizes in restaurants (6). The questions addressed general strategies and specific methods for reducing the calories of menu items, the magnitude of calorie reduction that was feasible, factors and barriers influencing the success of reduced-calorie items, and their influence on customer intake. The survey also collected information on respondent characteristics, including age, sex, years employed in the restaurant industry, primary employment position, type of dining establishment, and familiarity with the calorie content of menu items. Six of the survey items asked respondents to assign ranks (on the basis of importance or likelihood) to a number of predetermined options, such as menu changes, recipe strategies, or barriers to change. Eight items were completed by using rating scales to indicate the degree of agreement with a statement or the likelihood of success of a strategy. Nine items requested the respondent to select one response from among multiple choices.

The initial survey was reviewed by 12 chefs from a variety of dining establishments who had characteristics similar to the target population, and the survey was modified based on their feedback. The final 23-item survey was converted to a machine-readable format by the Penn State Survey Research Center. The test-retest reliability of the survey was assessed in a group of 25 chefs attending a chapter meeting of the American Culinary Federation. The participants were provided with a second copy of the survey, which they were asked to complete one week after the original copy and return by mail. Twenty chefs returned the second survey, giving a response rate of 80%. The kappa statistic for agreement between the two administrations of the survey averaged 0.76 for the items that assessed opinions (range 0.46 to 1.00), and 0.98 for items that assessed participant characteristics (range 0.91 to 1.00), indicating a good degree of agreement.

Data collection

A total of 699 surveys were distributed to a convenience sample of chefs attending meetings of the American Culinary Federation and the Research Chefs Association in Cincinnati, OH; Williamsburg, VA; Salt Lake City, UT; Kansas City, KS; Las Vegas, NV; and Seattle, WA in the spring and summer of 2008. At the start of one session at each of these meetings, an announcement was made regarding the survey and attendees were provided with a copy of the survey and a letter describing the research. Participants were told that the purpose of the survey was to obtain information from chefs about their experiences and opinions regarding healthy menu items served in restaurants. Respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary, and implied consent was obtained through completion of the survey; participants were required to be at least 18 years old. Personally identifying information was not collected from respondents. Surveys were collected approximately 15 minutes after distribution. The machine-readable surveys were scanned and converted to data files by the Penn State Survey Research Center. The study was approved by the Office for Research Protections of The Pennsylvania State University and the Office of Research Compliance of Clemson University.

Data analysis

Data were summarized using descriptive statistics of frequencies and percentages. For survey items that were assessed using rating scales with the same response options, repeated measures logistic regression was used to test for significant differences in the distribution of responses across items. Significance values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction. Ordinal logistic regression was used to assess whether the distribution of responses to any question was influenced by individual characteristics of respondents (age, sex, employment position, years employed in the industry, or degree of familiarity with menu calorie content). The results of logistic regression are reported in terms of proportional odds ratios (OR) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of survey respondents

Of the 699 surveys that were distributed, 460 were returned, giving a response rate of 66%. Twenty surveys had insufficient data to be useable and eight were from participants under age 18 and were excluded from analysis, leaving 432 surveys in the final sample. Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The majority of respondents had been employed in the restaurant industry for 20 years or more. The most common employment categories were corporate-level position or restaurant owner, and executive chef or kitchen manager, but a substantial number of respondents were culinary educators and restaurant chefs. Survey participants worked in a variety of dining establishments and represented all major regions of the United States.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 432 chefs who completed a survey about reduced-calorie menu items in restaurants

| Characteristic | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 19 to 30 | 19% | 80 |

| 31 to 50 | 51% | 219 |

| 51 and above | 31% | 133 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 66% | 283 |

| Female | 34% | 148 |

| Primary position in restaurant | ||

| Corporate-level position, restaurant owner, or restaurant manager | 31% | 134 |

| Culinary educator | 22% | 96 |

| Executive chef or kitchen manager | 28% | 120 |

| Chef or student chef | 19% | 80 |

| Years in the restaurant industry | ||

| Less than 5 | 16% | 68 |

| 5 to 9 | 9% | 41 |

| 10 to 14 | 10% | 43 |

| 15 to 19 | 11% | 48 |

| 20 or more | 54% | 232 |

| Restaurant type | ||

| Fine dining | 35% | 148 |

| Casual or family dining | 37% | 155 |

| On-site dining or contract feeding | 21% | 87 |

| Quick service or fast food | 8% | 32 |

Respondents reported a variable degree of familiarity with the calorie content of items on the menu of their restaurant: 12% of chefs said that they were extremely familiar, 33% were very familiar, 49% were somewhat familiar, and 7% were not at all familiar. Women reported greater familiarity with menu calorie content than men, regardless of job position (p = 0.006; OR = 1.69 [CI 1.16 - 2.45]); 53% of women reported that they were very or extremely familiar with the calories on their menu compared to 40% of men.

Strategies for reducing the calorie content of menu items

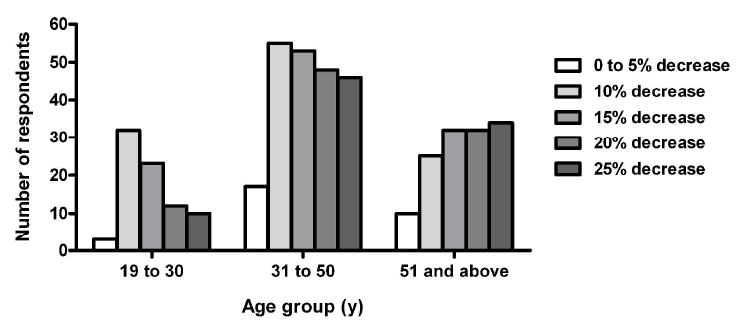

When asked about the magnitude of reduction in the calorie content of menu items, 72% of chefs reported that it could be decreased by 10 to 20% before customers would notice, and 21% thought that a reduction of at least 25% was possible. The response to this question differed significantly across age groups (p = 0.005; Figure 1). Chefs in older age groups were more likely to report that a higher decrease in calorie content could occur before customers would notice than those aged 30 or less (OR 1.42 [CI 1.11 - 1.82]). The magnitude of feasible calorie reduction was not significantly influenced by respondent job position, duration of employment in the restaurant industry, or degree of familiarity with menu calorie content.

Figure 1.

The largest decrease in the calorie content of menu items that could occur before customers would notice, according to 432 chefs in three age groups: 19 to 30 years (n = 80), 31 to 50 years (n = 219), and 51 years and above (n = 133). The distribution of responses differed significantly across age groups as assessed by logistic regression (p = 0.005). Chefs in older age groups were more likely to report that a higher decrease in calorie content could occur before customers would notice than were those aged 30 or less (OR 1.42 [95% CI 1.11 - 1.82]). Due to the small number of responses in the “no decrease” and “5% decrease” categories, these data were combined.

When chefs were asked to choose a recipe manipulation to reduce the calories in two specific menu items, they were more likely to select strategies for reducing energy density than for reducing portion size (Table 2). A significantly greater proportion of chefs reported that they would decrease the fat content of beef stew (thus reducing energy density) compared to those who would reduce the portion size (p < 0.0001; OR 3.53 [CI 2.44 - 5.06]), and a similar result was seen for altering the recipe of apple pie à la mode (p = 0.004; OR 1.66 [CI 1.17 - 2.35]). Adding fruit or vegetables, another strategy that reduces energy density, was the third most commonly chosen manipulation for both recipes (p < 0.007). In contrast, the frequency of these two strategies was reversed when chefs were given a choice between two general approaches for changing menu items to reduce customer calorie intake. Most chefs selected “reducing portion size” (69%) as the more effective strategy rather than “reducing calories per bite”, that is, decreasing energy density (31%). The opinions of chefs on these strategies were significantly affected by their employment position. The corporate-level chefs and restaurant owners and managers were more likely than restaurant chefs and executive chefs to choose a specific recipe manipulation of reducing portion size (p = 0.02; OR 1.3 [CI 1.1 - 1.6] for both recipes) and to choose the general approach of reducing portion size over energy density (p = 0.012; OR 1.27; CI 1.06 -1.54).

Table 2.

Recipe modifications most likely to be used by 432 chefs to reduce the calorie content of two dishes1

| Beef Stew | Apple Pie à la Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipe modification | % | N | % | N |

| Reduce fat | 52% | 225 | 43% | 188 |

| Reduce portion size | 24% | 102 | 32% | 137 |

| Add fruits or vegetables | 15% | 66 | 17% | 74 |

| Reduce carbohydrates | 5% | 23 | 6% | 27 |

| Add fiber | 3% | 14 | 3% | 11 |

| Reduce protein | 2% | 9 | 3% | 12 |

Frequencies do not sum to the total number of respondents because some respondents ranked more than one choice as the most likely to be used.

Including reduced-calorie items on the menu

The majority of chefs thought that each of four proposed methods for reducing the calories on their menu would be successful in terms of sales, but they showed preferences among the methods. Respondents were more likely to rate reducing the calorie content of selected menu items as being successful than reducing the portion size of high-calorie items (61% versus 53%; p < 0.0001). They were also more likely to rate introducing a new reduced-calorie item as being successful than reducing the calories of an existing item (67% versus 54%; p < 0.0001). Chefs reported that they would be most likely to reduce the calorie content of entrées (40%), followed by side dishes (24%; p < 0.0001), and less likely (p = .017) to modify appetizers (19%) and desserts (18%). Those with a greater degree of familiarity with the calorie content of their menu were more likely to think that modifying an existing item would be successful (p = 0.025; OR 1.31 [CI 1.03-1.66]) and to choose to reduce the calories of appetizers (p = 0.009; OR 1.51 [CI 1.11-2.06]) than those who were less familiar with menu calorie content.

The greatest barrier to including reduced-calorie items on the menu was reported to be “low consumer demand”, chosen by 38% of chefs, significantly more (p = 0.0002) than chose “need for staff skills and training” (24%) and “high ingredient cost” (18%). The remaining options were selected as the greatest barrier by few respondents: “high labor cost” (7%), “limited ingredient availability” (7%), “too much time to cook or assemble food” (4%), and “short ingredient shelf life” (3%).

Among several characteristics of reduced-calorie foods that may affect their success on a restaurant menu, a majority of respondents (71%) ranked taste as the most important factor (p < 0.0001; Table 3). The next most common factors were food appearance and health promotion, with significantly fewer respondents selecting the characteristics of calorie content, advertising, and good value (p = 0.017). The ranking of the importance of these characteristics depended on the employment position of the respondent (p = 0.0002; OR 1.44 [CI 1.18 - 1.74]). Compared to other positions, corporate-level chefs and restaurant owners and managers were even more likely to rank taste as the most important characteristic for the success of reduced-calorie foods, and less likely to select appearance or health promotion as the most important factor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of reduced-calorie menu items ranked as the most influential for success by chefs in different positions1

| Characteristic | Restaurant chefs, student chefs (n = 80) | Executive chefs, kitchen managers (n = 120) | Culinary educators (n = 96) | Corporate-level chefs, restaurant owners & managers (n = 134) | Total (n = 430) | Effect of employment position2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Tastes great | 58% | 46 | 67% | 80 | 75% | 72 | 80% | 107 | 71% | 305 | 0.0002 | 1.44 (1.18-1.74) |

| Appealing appearance | 20% | 16 | 14% | 17 | 11% | 11 | 6% | 8 | 12% | 53 | 0.002 | 0.65 (0.50-0.86) |

| Promotes good health | 16% | 13 | 13% | 15 | 3% | 3 | 7% | 10 | 9% | 41 | 0.013 | 0.68 (0.51-0.92) |

| Lowers calorie content | 10% | 8 | 3% | 3 | 5% | 5 | 5% | 7 | 5% | 23 | NS | NS |

| More advertising | 8% | 6 | 5% | 6 | 2% | 2 | 1% | 1 | 3% | 15 | 0.008 | 0.47 (0.28-0.82) |

| Good value | 3% | 2 | 4% | 5 | 5% | 5 | 1% | 2 | 3% | 14 | NS | NS |

Frequencies do not sum to the total number of respondents because some respondents ranked more than one choice as the mostinfluential for success.

Significance of effect of employment position on proportion of respondents who ranked the characteristic as the most influential, as assessed by logistic regression. Odds ratios are calculated in comparison to the reference category of corporate-level chefs. OR; proportional odds ratio. 95% CI; 95% confidence interval. NS; not significant.

Influence of menu calorie content on customer behavior

Respondents had mixed opinions regarding the effect of the calorie content of food served in restaurants on customer behavior. The majority of chefs (65%) thought that high-calorie food in restaurants is a problem for people trying to control their weight. A smaller proportion (55%; p = 0.002) agreed that it was the customers’ responsibility to eat an appropriate amount when served higher-calorie food. Opinions were divided about whether the calorie content of restaurant foods influences the amount of calories that customers eat (p = 0.005); 47% agreed, 38% disagreed, and 15% were neutral. The distribution of opinions on this issue depended on employment position (p < 0.014). Corporate-level chefs and restaurant owners and managers were the most divided on whether calorie content influences customer calorie intake; they were more likely to disagree (48%; OR 1.33 [CI 1.10 – 1.62]) and less likely to be neutral (7%; OR 0.72 [CI 0.55 – 0.94]) than were restaurant-level chefs (23% and 24%, respectively).

Respondents’ opinions were divided regarding the effect of putting calorie information for all foods on the menu: 36% of chefs thought that menu labeling would be successful in terms of sales and 38% thought that it would be unsuccessful, with 26% being neutral. Opinions on menu labeling differed according to the employment position of the respondent (p < 0.0001; OR 1.39 [CI 1.18 - 1.64]). Restaurant chefs were more likely to rate menu labeling as successful for sales (48%) than were corporate-level chefs and restaurant owners and managers (26%).

DISCUSSION

In this survey of 432 chefs from a broad range of employment positions and dining establishments, nearly all of the respondents reported that the calories in restaurant menu items could be reduced substantially without customers noticing. The chefs identified several practical approaches for reducing the energy content of foods and there was broad consensus on the factors influencing the success of these items. There was less agreement, however, about successful methods of including reduced-calorie items on the menu and the barriers to doing so, as well as the effect on customers. Thus, most of the chefs surveyed thought that it was feasible to reduce the calorie content of menu items, but they had concerns about customer responses to such changes.

Laboratory-based studies support the belief of the majority of chefs in this survey that the calorie content of menu items could be reduced by 10 to 25% without customers becoming aware of the change. In controlled feeding studies, participants rarely reported noticing decreases in energy density of 20 to 30%, although decreases in portion size of 25 to 40% tended to be recognized (8-11). In these studies, reductions in food energy density generally resulted in a greater decrease in energy intake than did reductions in portion size (8-9). Consistent with these findings, survey respondents were more likely to select methods that reduced energy density, both to decrease the calorie content of specific recipes and to introduce menu changes, rather than choosing to reduce portion size. Many chefs, however, seemed to be unfamiliar with the concept of energy density as expressed by “reducing calories per bite”, since a relatively small proportion identified this as a general strategy for reducing calories. Chefs also seemed less aware of the role of water-rich ingredients such as fruit and vegetables in reducing energy density. Incorporating more nutrition education in culinary training could provide a greater understanding of the conceptual basis for recipe modifications used in creating reduced-calorie menu items.

Most chefs in the survey were receptive to opportunities for reducing the calories on their menus; the majority reported that all the proposed methods of changing the menu would be successful. Respondents thought it was more acceptable, however, to introduce new items rather than alter existing dishes, particularly higher-calorie items such as appetizers and desserts. It is likely that this opinion is related to the chefs’ belief that taste was the primary factor influencing customer food choice, a finding which has been documented previously (5,12). Chefs may have been reluctant to change higher-calorie items because of concerns about adverse effects on palatability, and thus potential risks to profits (13). Survey respondents identified the main barriers to including reduced-calorie items on the menu as low consumer demand, the need for staff skills and training, and high ingredient cost. Similar concerns have been identified in interviews with senior executives at leading U.S. restaurant chains (14). It is notable that in the present survey, respondents who were more familiar with the calorie content of their menus had more confidence in the success of altering high-calorie items. These results further highlight the importance of continuing innovation in culinary practice, emphasizing skills needed to create reduced-calorie dishes that promote health while ensuring that costs are controlled and taste and acceptability are not compromised.

The majority of respondents in this survey agreed that high-calorie food served in restaurants poses a problem for people trying to control their weight. However, only 47% of the chefs believed that the calorie content of food served in restaurants influences the amount of calories that people consume. This opinion contrasts with that of a previous survey regarding portion size, which found that 86% of chefs agreed that the portion sizes served in restaurants influence the amount eaten by customers (6). The underlying reasons for the mixed opinions of chefs about the influence of restaurant food on customer intake require further elucidation. If chefs lack confidence in their ability to beneficially affect customer energy intake, they may be reluctant to modify menu items. A different approach to influencing consumer intake in restaurants that is increasingly being implemented is the provision of nutrition information on menus. In the present survey, respondents were divided in their opinions on whether this strategy would be successful in terms of sales. As the adoption of menu labeling becomes more widespread and its impact is evaluated more rigorously (15-17), chefs will need to stay informed about the most effective ways to use nutritional information to promote sales and encourage healthy eating.

An advantage of the present survey is that it was administered to a large, diverse group of chefs, allowing comparison between respondents with different characteristics. The finding that older chefs thought it was feasible to reduce calorie content to a greater extent than did younger chefs was similar to a previous report, which found that older chefs served smaller portion sizes than did younger chefs (6). A possible explanation for this result is that older chefs experienced environmental norms of calories and portion sizes before “supersizing” became common (18-20). This may indicate a need for further education among young chefs about the energy content and portion size of dishes that are both feasible and appropriate. The present survey also showed that compared to restaurant-level chefs, respondents who were corporate-level chefs and restaurant owners and managers held different opinions about factors influencing the success of menu items and their effect on customer intake. It is likely that the primary concerns of chefs at management levels were related to the factors they believe will increase sales or profit (14). Thus, it will be increasingly important that chefs in these influential positions stay informed of customer changes in health-related attitudes toward foods eaten away from home. A limitation on of the study is that the respondents were a convenience sample of chefs attending culinary meetings, and it is not known how representative they are of all chefs in the US. In addition, participants were restricted to selecting from predetermined responses; future surveys could include more open-ended questions to allow respondents to provide additional responses according to their personal experience.

The results of this survey show that most chefs believe that the calorie content of restaurant food can be reduced substantially without customers noticing. Respondents identified several strategies for decreasing the calorie content of menu items, including decreasing the energy density of dishes and reducing their portion size. The survey findings highlight respondents’ belief in the importance of consumer demand and taste in the success of reduced-calorie items on restaurant menus. Although many respondents acknowledged the contribution of restaurant menu items to customer calorie intake, many still placed the responsibility on the customer to consume an appropriate amount of calories when eating in restaurants. The results of this survey support the need for ongoing collaboration between chefs and public health professionals to ensure that appealing reduced-calorie menu items are more widely available in restaurants and that research is directed towards understanding the most effective ways to develop and promote these items.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant DK039177 (to BJR). The authors would like to thank the American Culinary Federation, the Research Chefs Association, and chef respondents for their participation in this research.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009;87:123–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Ann Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Eating out in America, 1987-2000: trends and nutritional correlates. Prev Med. 2004;38:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Briefing Room: Food CPI Index and Expenditures. 2008 Available online at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/CPIFoodAndExpenditures.

- 5.Keystone Center. Washington, DC: The Keystone Center; 2006. The Keystone forum on away-from-home foods: opportunities for preventing weight gain and obesity. Available online at: http://keystone.org/files/file/about/publications/Forum_Report_FINAL_5-30-06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condrasky M, Ledikwe JH, Flood JE, Rolls BJ. Chef’s opinions of restaurant portion sizes. Obesity. 2007;15:2086–2093. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolls BJ. The relationship between dietary energy density and energy intake. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Reductions in portion size and energy density of foods are additive and lead to sustained decreases in energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:11–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kral TVE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Combined effects of energy density and portion size on energy intake in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:962–968. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS, Wall DE. Increasing the portion size of a sandwich increases energy intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Kral TVE, Meengs JS, Wall DE. Increasing the portion size of a packaged snack increases energy intake in men and women. Appetite. 2004;42:63–69. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00117-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Dougherty M, Harnack LJ, French SA, Story M, Oakes JM, Jeffery RW. Nutrition labeling and value size pricing at fast-food restaurants: a consumer perspective. Am J Health Promot. 2006;20:247–250. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Economos CD, Folta SC, Goldberg J, Hudson D, Collins J, Baker Z, Lawson E, Nelson M. A community-based restaurant initiative to increase availability of healthy menu options in Somerville, Massachusetts: Shape Up Somerville. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glanz K, Resnicow K, Seymour J, Hoy K, Stewart H, Lyons M, Goldberg J. How major restaurant chains plan their menus: the role of profit, demand, and health. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harnack LJ, French SA. Effect of point-of-purchase calorie labeling on restaurant and cafeteria food choices: a review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:51. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo T, Jarosz CJ, Simon P, Fielding JE. Menu labeling as a potential strategy for combating the obesity epidemic: a health impact assessment. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1680–1686. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbel B, Kersh R, Brescoll VL, Dixon LB. Calorie labeling and food choices: a first look at the effects on low-income people in New York City. Health Aff. 2009;28:w1110–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young LR, Nestle M. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:246–249. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell DC, Mickle SJ, Goldman JD, Cook A. Foods commonly eaten in the United States, 1989-19991 and 1994-1996: Are portion sizes changing? J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:41–47. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ. Portion sizes and the obesity epidemic. J Nutrition. 2005;135:905–909. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]