Abstract

Background

Beta-blocker therapy has become a mainstay therapy for the over 5 million patients with chronic heart failure in the United States. Variation in clinical response to β-blockers is a well-known phenomenon and may be because of genetic differences between patients. We hypothesized that variation in genes of the endothelin system mediate the clinical response to β-blockers in heart failure.

Methods

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in six endothelin system genes were genotyped in 309 heart failure patients in a randomized trial of bucindolol versus placebo therapy. We adjusted for multiple comparisons and tested for association between genotype and time to two prospective endpoints.

Results

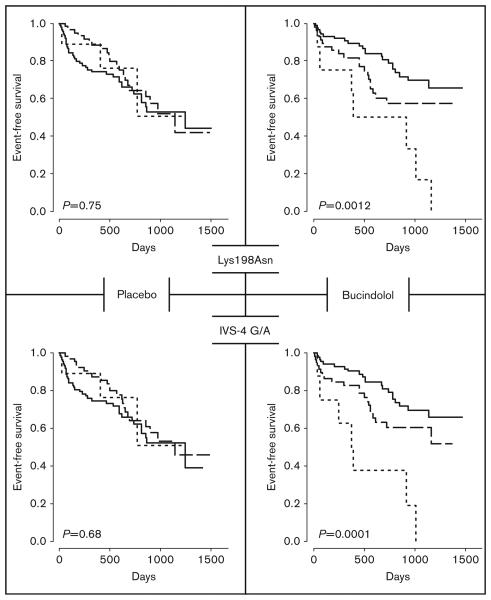

Nine SNPs were sufficiently common to undergo statistical analysis. The SNPs had no significant effect on prospective outcomes in the placebo group, or on the primary endpoint of time to death in either arm. Two SNPs (IVS-4 G/A and Lys198Asn) in the endothelin-1 gene, however, predicted time to the combined endpoint of heart failure hospitalization or all-cause death in bucindolol-treated patients. The alleles at these SNPs were in tight linkage disequilibrium appearing on either of two complementary haplotypes. A ‘dose–response’ trend was observed, with participants carrying the rarer haplotype having the highest hazard ratios as compared to the relative ‘protective’ effect of the common haplotype.

Conclusion

A common endothelin-1 gene haplotype may be a pharmacogenetic predictor of a favorable clinical response to β-blocker therapy in heart failure patients. The existence of a less common ‘high-risk’ haplotype could identify a subpopulation of heart failure patients destined to respond poorly to β-blocker therapies.

Keywords: β-blockers, endothelin, genetics, heart failure, pharmacogenetics

Introduction

Beta-blocker therapy is a standard treatment for systolic heart failure and reduces all-cause mortality by 34–65% [1-3]. These data are in agreement with other large drug trials where only between 25 and 60% of patients benefit from exposure to medication as compared to placebo [4,5]. Observed variation in response to medication is frequently mediated by genetic factors [4,6]. In the case of heart failure, the limited number of DNA banks established with large prospective trials has historically limited discovery of pharmacogenetic markers of drug response. More recently, success in identifying pharmacogenetic predictors of drug response in heart failure have been reported [7].

The endothelin gene system (EGS) is a candidate modifier pathway for heart failure [8-10]. Short endothelin peptides bind to endothelin receptors and are potent mediators of vasoconstriction, endothelial cell growth, and vascular tone [11,12]. Changes in cardiac inotrophy and chronotrophy are mediated also through binding of endothelin-to-endothelin receptors A and B. Endothelin-1 is the predominant isoform expressed in the human heart and promotes cardiomyocyte contractility and hypertrophy [12,13]. Genetic variation in endothelin has been associated with blood pressure, left-ventricular hypertrophy, and heart failure [14-16]. Moreover, biologically active endothelins interact with other ‘neurohormonal’ networks including the adrenergic and angiotensin systems, by pharmacologic cross talk [17-20].

Earlier genetic association studies of EGS single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) focused on hypertension, arterial stiffness, vascular reactivity, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, and heart failure [21-28]. A majority of these studies were not prospective and were subjected to the well-known limitations of genetic association studies, including false-positive results. Given the importance of the EGS on vascular phenotypes including cardiac inotropic and chronotropic effects, we hypothesized that clinical response to β-blocker medication could be mediated by EGS variation and studied EGS SNPs for evidence of pharmacogenetic associations in a clinical population. Wishing to avoid problems common to case–control genetic association studies, we used a pharmaco-genetic study design of bucindolol versus placebo in a population from a large, prospective, randomized trial of moderate-to-severe heart failure [29]. Bucindolol is a β-blocking agent with sympatholytic and vasodilator properties. Although it is not yet approved for clinical heart failure therapy, variation in outcomes in subpopulations of the study suggested us that underlying genetic differences may be responsible for observed differences in efficacy.

Methods

Clinical studies

Three hundred and nine patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy were studied from the β-blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST) [29]. BEST was a multicenter, randomized, prospective trial of patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure and an ejection fraction less than or equal to 35% comparing mortality in adults treated with placebo or the nonselective β-blocker bucindolol. The trial was originally designed to have 85% power to detect a 25% reduction in all-cause mortality on bucindolol and was not designed with respect to power to detect genetic interactions or other effects [30], but was stopped at the seventh interim analysis because of a loss of investigator equipoise; at study termination the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality was not statistically significantly reduced in the bucindolol arm. The BEST DNA bank, initiated in the study's second year to ‘provide a resource for investigators examining possible genetic components of heart failure and to enable scientists to identify at-risk populations who may benefit from early intervention’, collected samples from 38% (1040) of the 2708 original participants. We requested samples from idiopathic dilated cases, rather than the entire DNA cohort, to ensure a more homogenous heart failure population. In particular, we sought to avoid studying genetic ischemic forms of heart failure, where acquired macrovascular changes in arterial stiffness or tone could potentially mask or override inherent microvascular phenotypes mediated by variation in endothelin genes. The sample size of this study was predicated on the number of participants with samples in the DNA bank who met these criteria. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and all DNA was coded to maintain confidentiality. The genotyping project was approved by the BEST DNA Bank Oversight Committee and by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Selection of endothelin gene system polymorphisms

EGS SNPs were selected before the release of HapMap data using an extensive literature review and a search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information SNP database (dbSNP build 108). The six EGS genes studied included three endothelin genes (EDN1, EDN2, EDN3), both endothelin receptors A and B (EDNRA, EDNRB), and the endothelin-converting enzyme 1 (ECE1). SNPs predicting changes in amino acid sequence of EGS proteins were selected for study. SNPs in noncoding regions (intronic and promoter regions) and synonymous SNPs were also studied when earlier reports suggested a positive association with a phenotype in humans and/or a functional effect had been demonstrated in an in-vitro model. Twenty-two EGS SNPs, including 15 nonsynonymous SNPs, were identified by searching published literature and the dbSNP database (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1) [15,26,27]. At the start of the study, population frequencies of 13 EGS SNPs were not reported in dbSNP and these SNPs proved rare in our population and were not analyzed further (rs number: 5798, 5799, 457755, 457651, 5345, 5346, 1801710, 2228271, 5347, 5350, 5352, 3026902, 3026906). Nine SNPs in four genes with minor allele frequencies of 5% or greater were included in the statistical analysis. In-silico analyses of EGS SNPs for predicted effects on protein secondary structure used GOR IV and PSIPRED algorithms [31,32]; possible effects on splicing used the GeneSplicer program [33].

Table 1.

Endothelin gene system polymorphisms initially selected for study

| Gene | rs number | SNP | Protein | Location | NCBI MAF |

BEST MAF (n=309) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDN1 | 1800997 | −138 del | No change | 5′ UTR | 0.19 | 0.25 |

| A | ||||||

| 5369 | G/A | Glu106 | Exon 3 | 0.11 | 0.12 | |

| 2071942 | G/A | No change | IVS-4 | 0.16 | 0.25 | |

| 5370 | G/T | Lys198Asn | Exon 5 | 0.26 | 0.24 | |

| EDNRA | 1801708 | A/G | No change | 5′ UTR | 0.49 | 0.44 |

| 5333 | C/T | His323 | Exon 6 | 0.32 | 0.34 | |

| 5343 | C/T | No change | 3′ UTR | 0.24 | 0.34 | |

| EDNRB | 5351 | A/G | Leu277 | Exon 5 | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| ECE1 | 1076669 | C/T | Thr341Ile | Exon 9 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

BEST, Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial; IVS, intervening sequence (intron); allele frequency for rs1800997 [27]; MAF, minor allele frequency listed as reported in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) dbSNP (build 127); NR, not reported; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; UTR, untranslated region.

Genotyping

Genotyping was done by the University of Colorado Cardiovascular Institute laboratory using a MSQ96MA Pyrosequencer (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden) and primers were designed using software provided by the manufacturer. PCR reactions were first performed with primer pairs flanking each SNP; one of each primer pair also contained an M13 sequence (5′-Biotin-CAGGAAACAG CTATGAC-3′) to allow for incorporation of a biotinylated ‘universal’ primer containing the same M13 sequence. Pyrosequencing was then performed using sequencing primers designed specifically for each SNP (Supplemental Table 2). Each of the nine SNPs analyzed statistically (Table 1) underwent repeated genotyping of a random subset of 10% of the samples for validation and quality control.

Statistical analysis

We examined time to each of two endpoints: the BEST study's primary endpoint of all-cause death and a combined endpoint comprised of first heart failure hospitalization or all-cause death, using the Cox proportional hazards model. Genotype was treated a priori as a continuous variable, consistent with an allele dosage effect. Analyses were conducted using R (version 2.1.1) and SAS (version 9.1.3; SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Primary analyses consisted of separate tests of a main genotype effect on time to event for each SNP within each treatment arm: placebo (N=159) and bucindolol (N=150). Secondary analyses, in the combined sample (N=309), consisted of tests of a genotype-treatment pharmacogenetic interaction and of a main genotype effect independent of treatment arm. Secondary analyses, comprised of interaction tests and estimation of within-genotype bucindolol:placebo hazard ratios (HRs), were also performed. We did not include ethnicity as a factor in our initial Cox models, because of the relatively small sample. Post-hoc analyses (within ethnic group, and including ethnicity–genotype interactions), however, were used to explore whether initial results were because of unaccounted for ethnic stratification. Linkage dis-equilibrium was assessed by taking the R2 value (squared correlation) of the genotypes (coded as 0, 1, or 2) between two SNPs.

We had two a priori reasons for emphasizing within-treatment arm effects, over the more usual interaction test. As a gene–treatment interaction effect cannot exist without a main genetic effect in at least one of the treatment groups, we felt it logical to first test whether there was any such main genetic effect before testing whether that effect differed in a way that depended on treatment (i.e. a pharmacogenetic interaction). Second, we considered relative power with approximately equal sample sizes, assuming a possible pharmacogenetic effect with no or a negligible effect of genotype in one group, say the placebo group, and a more substantial effect in the other, active-drug, group. In that case, the values of the active-drug genotype effect and the interaction effect (written as the difference of within-treatment effects) are the same. The standard error of the interaction effect is approximately √2×S, where S is the standard error of the within-treatment effect. Thus, the most powerful test for any type of genotype effect in this setting is the within-treatment test in the arm with a genetic effect. This is generally true, unless the genetic effects work in opposite directions in the two treatment arms. The test for a main genotype effect, independent of treatment group, would be the most powerful in the absence of a pharmacogenetic effect.

The rationale for within-treatment arm tests has limitations. It depends on relatively equal sample sizes in the two groups and assumes that a deleterious variant in one group is not actively beneficial in the other. Furthermore, the conclusions that can be drawn from within-treatment arm tests differ from those of the genotype–treatment interaction test. Within-treatment tests can only demonstrate the existence of an association between a genetic polymorphism and an outcome, which may or may not be related to drug response. Only an interaction test has the potential to demonstrate the presence of a true pharmacogenetic interaction. The within-treatment approach also differs from more traditional subgroup analysis, which tests treatment effect within genotypically defined groups [34]. Subgroup tests within genotype can demonstrate a treatment benefit within a patient subgroup, but do not show that benefit actually depends on genotype. To account for the large number of simultaneous tests, adjusted P values obtained from a multiple-testing permutation procedure are reported [35]. On the basis of our actual data set, 5000 random data sets were generated by randomly permuting the time to event data relative to the genotype data, separately for patients on placebo and for patients on bucindolol. Adjusted P values for all within-treatment arm tests are based on 36 comparable tests (2 outcomes × 2 treatment arms × 9 SNPs). Adjusted P values for interaction tests are based on 18 tests (2 outcomes × 9 SNPs). Kaplan–Meier plots and log-rank tests were also examined. All P values were based on two-sided tests. The statistical analysis was performed at the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program DNA Bank Coordinating Center, California, USA.

Results

The placebo and bucindolol groups were similar with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 2). No significant differences between the placebo and bucindolol groups with respect to baseline heart rate, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, or baseline cardiovascular medications were observed (data not shown). Genotype frequencies at all nine EGS SNPs were consistent with earlier reports (Table 1). All but one SNP were in the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; disequilibrium at EDNRA A/G (5′ untranslated region) seemed to be generated by ethnic stratification, as genotypes were in the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium when analyzed within each ethnic group.

Table 2.

Comparison of treatment groups

| Variable | Placebo (N=159) |

Bucindolol (N=150) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (25%, 75% quartiles) | 57.0 (48, 67) | 59.0 (47, 67) | 0.50 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 106 (67%) | 107 (71%) | 0.38 |

| Female | 53 (33%) | 43 (29%) | |

| Race | |||

| Non-Black | 128 (81%) | 112 (75%) | 0.22 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 31 (19%) | 38 (25%) | |

| NYHA Class | |||

| Class III | 151 (95%) | 141 (94%) | 0.71 |

| Class IV | 8 (5%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Median duration of HF in months | 24.0 | 26.5 | 0.94 |

| Diabetes | 39 (25%) | 50 (33%) | 0.09 |

| Hypertension | 72 (45%) | 76 (51%) | 0.34 |

| Current tobacco use | 23 (14%) | 20 (13%) | 0.77 |

| Mean arterial pressure (SD) | 87.4 (11.8) | 88.2 (12.3) | 0.56 |

| Mean LVEF (SD) | 24.5 (7.0) | 24.5 (7.0) | 0.93 |

| Mean serum creatinine in mg/dL (SD) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.3) | 0.08 |

| Mean plasma norepinephrine in pg/ml (SD) | 460.5 (311) | 468.3 (253) | 0.83 |

HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation.

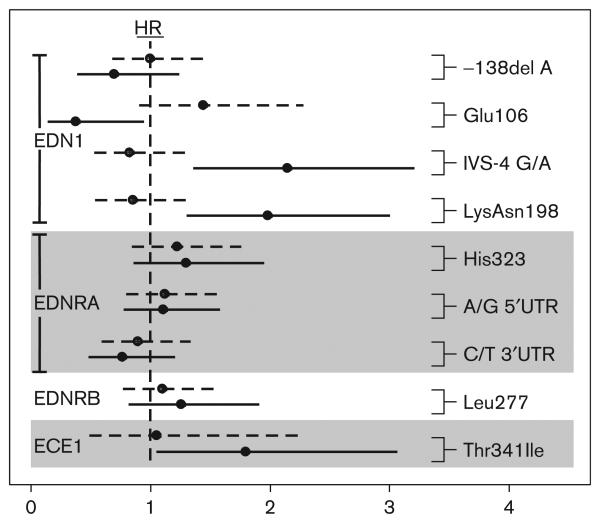

After controlling for multiple testing, no EGS variant had a significant effect on time to all-cause death in either treatment arm, or on time to the combined outcome in patients on placebo. Two SNPs in EDN1 [G/A intervening sequence (IVS)-4 and G/T Lys198Asn], however, had highly significant genotype effects on time to the combined endpoint of first heart failure hospitalization or all-cause death for patients on bucindolol, even after rigorous adjustment for multiple tests (Figs 1 and 2, Table 3). The alleles in the more common G-Lys haplotype were each associated with a better outcome. This pharmacogenetic interaction resulted in an apparent beneficial effect of bucindolol in the common homo-zygotes, a harmful effect in the rare homozygotes and a neutral effect in the heterozygotes (Table 4). Only the beneficial effect in the common homozygote group, which had the largest numbers of participants and events, was statistically significant. The results for hospitalization are similar to those for the combined endpoint (data not shown). Results for hospitalization are similar to those for the combined endpoint. We felt including another post-hoc analysis, however, would not add to the results. When hospitalization alone is considered, excluding deaths without earlier hospitalization seems to decrease precision, increasing the standard error by about 10%.

Fig. 1.

Time to the combined event of first heart failure hospitalization or death for endothelin-1 polymorphisms Lys198Asn (top) and intervening sequence (IVS)-4 G/A by genotype. Common homozygotes, heterozygotes, and rare homozygotes are depicted by the solid, dashed, and dotted lines respectively. The data are separated by treatment group with placebo-treated and bucindolol-treated patients on the left and right, respectively. P values are for the 2 degrees of freedom log-rank test. Event/number (for common homozygotes, heterozygotes, and rare homozygotes, respectively) for Lys198Asn: (placebo: 36/89, 21/60, 3/9; bucindolol: 22/87, 20/55, 7/8) and IVS-4 G/A: (placebo: 35/87, 23/63, 3/9; bucindolol: 21/84, 21/58, 7/8).

Fig. 2.

Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals by treatment for the Cox-model effect of a one-allele change in genotype, unadjusted for multiple comparisons for each endothelin system gene. ECE1, endothelin-converting enzyme-1; EDN1, endothelin-1; EDNRA, endothelin receptor A; EDNRB, endothelin receptor B; IVS, intervening sequence. Dashed and solid lines indicate the HRs for placebo and bucindolol groups, respectively. Values greater than 1 indicate greater risk associated with the less common allele.

Table 3.

Effects of one-allele changes in the allele dosage Cox model

| Treatment | SNP | Group | N | E | MAF(%) | HR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bucindolol | G/A (IVS-4) | All | 150 | 49 | 25 | 2.2 | 1.4–3.3 | < 0.001 | 0.01 |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 100 | 27 | 24 | 1.9 | 1.1–3.5 | 0.02 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 38 | 16 | 22 | 1.6 | 0.7–3.8 | 0.30 | |||

| Lys198Asn | All | 150 | 49 | 24 | 2.0 | 1.3–3.0 | 0.001 | 0.03 | |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 100 | 27 | 23 | 1.9 | 1.1–3.3 | 0.03 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 38 | 16 | 22 | 1.5 | 0.7–3.1 | 0.25 | |||

| Placebo | G/A (IVS-4) | All | 159 | 61 | 25 | 0.8 | 0.5–1.3 | 0.41 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 112 | 41 | 25 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.6 | 0.8 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 31 | 16 | 26 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.2 | 0.12 | |||

| Lys198Asn | All | 158 | 60 | 25 | 0.9 | 0.6–1.3 | 0.48 | 1.00 | |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 111 | 40 | 24 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.6 | 0.78 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 31 | 16 | 27 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.2 | 0.13 |

Data shown are for combined endpoint (first heart failure hospitalization or all-cause mortality); hazard ratios (HRs) associated with each copy of allele A or Asn, respectively, under an allele dosage model. For bucindolol by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) interaction tests, P values (adjusted P values**) were 0.002 (0.03) and 0.006 (0.07) for intervening sequence (IVS)-4 and Lys198Asn, respectively. A nonsignificant trend for interaction was observed for both SNPs for both ethnic subgroups. Post-hoc analyses by ethnic subgroup were not included in P value adjustments. All includes participants from other ethnicities.

Adjusted P value for 36 tests of genotype within-treatment arm in primary analysis.

Adjusted P values for 18 interaction tests.

CI, confidence interval; E, number of events; MAF, minor allele frequency; N, number of participants.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios for bucindolol versus placebo within EDN1 genotype

| SNP | Group | N | E | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G/A (IVS-4) | GG | 84 : 87 | 21 : 35 | 0.5 | 0.3–0.9 | 0.01 |

| GA | 58: 63 | 21 : 23 | 1.1 | 0.6–1.9 | 0.85 | |

| AA | 8:9 | 7:3 | 3.2 | 0.8–12.5 | 0.10 | |

| Lys198Asna | Lys/Lys | 87:89 | 22:36 | 0.5 | 0.3–0.9 | 0.02 |

| Lys/Asn | 55:60 | 20:21 | 1.1 | 0.6–2.0 | 0.77 | |

| Asn/Asn | 8:9 | 7:3 | 2.5 | 0.6–9.9 | 0.19 |

Data shown compare the effect of bucindolol to placebo on the combined endpoint (first heart failure hospitalization or all-cause mortality) separately for each genotype.

One individual was not successfully genotyped at Lys198Asn.

CI, confidence interval; E, number of events, bucindolol: placebo; HR, hazard ratio; N, number of participants, bucindolol: placebo.

G/A (IVS-4) and Lys198Asn were in tight linkage disequilibrium (genotype R2=0.85), appearing primarily in unphased genotypes consistent with the G-Lys and A-Asn haplotypes. Thus, it was not possible to distinguish statistically between the SNPs relative importance in a two-SNP model. Neither SNP was independently statistically significant in the presence of the other, although the null model with neither SNP was clearly rejected. EDN1 G/A (IVS-4) and Lys198Asn each had significant treatment–genotype interactions (Table 3). Two other SNPs, EDN1 Glu106 (P=0.04) and ECE1 Thr341Ile (P=0.03) had significant main effects for the combined outcome, but were not significant after adjustment for multiple tests. EDNRA His323 (P=0.03) had a significant treatment–genotype interaction for time to all-cause death, before adjustment for multiple tests. The test for a main genotype effect in the combined data set yielded no significant results for either outcome.

As Blacks were previously reported to experience a worse response in BEST, we conducted secondary analyses in the two largest ethnic subgroups: non-Hispanic Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites. Both G/A (IVS-4) and Lys198Asn showed significant effects for the combined outcome in non-Hispanic Whites in the bucindolol treated group; in Blacks where the sample size was much smaller, the HRs were consistent, but no longer significant. In each group, there was a nonsignificant trend for a treatment–SNP interaction for both G/A (IVS-4) and Lys198Asn. ECE1 Thr341Ile could not be tested in non-Hispanic Blacks, which included a single carrier of the minor allele. Its significance in bucindolol-treated participants increased when the analysis was restricted to non-Hispanic Whites (P=0.008). EDN1 Glu106 was significant in non-Hispanic Whites (P=0.03), but not in non-Hispanic Blacks.

We tested all possible two-SNP models including either EDN1 G/A (IVS-4) or Lys198Asn and one of the remaining seven SNPs, both with and without an SNP–SNP interaction term, in post-hoc analyses. ECE1 Thr341Ile was significant in the two-SNP models including either EDN1 G/A (IVS-4) (P=0.04) or Lys198Asn (P=0.04), but only in the no-interaction models. Thus, ECE1 Thr341Ile might contribute an effect on the combined outcome independent of the EDN1 SNPs. In the EDN1 Lys198Asn–ECE1 Thr341Ile model, the HRs are 1.97 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.31, 2.96] and 1.81 (95% CI: 1.04, 3.15), respectively. In the EDN1 G/A (IVS-4)–ECE1 Thr341Ile model, the HRs are 2.09 (95% CI: 1.37, 3.20) and 1.78 (95% CI: 1.02, 3.12), respectively. Thus, the effect of the ECE1 SNP is estimated to be almost as strong as those of the two EDN1 variants. The weaker statistical significance for ECE1 Thr341Ile may be because of its less balanced allele frequencies, which reduce power. In contrast, EDN1 Glu106 was no longer significant when added to a model including either G/A (IVS-4) or Lys198Asn. Thus, the significance of EDN1 Glu106 in a one-SNP model might merely reflect its highly significant linkage disequilibrium with those SNPs (P <0.001).

Results were qualitatively unchanged in other post-hoc analyses. Liggett et al. [7] previously genotyped reduced all-cause mortality in bucindolol-treated participants carrying the Arg-389 allele of the β-1-adrenergic receptor in the 1040 BEST DNA Bank participants. Our sample represents a subset of that earlier study. We obtained these genotypes for our participants and fit two-SNP models with one EDNs SNP and the β-1-adrenergic receptor Gly389Arg variant as a covariate. Estimates and significance results for the EDNs SNPs were essentially unchanged (Supplemental Table 3).

For all SNPs that were significant under the allele-dosage model used in primary analyses, neither a dominant nor a recessive genetic model fit better based on the value of the log-likelihood. In some of these cases, either the dominantor recessive model failed to detect significance. No nonsignificant SNP in the primary analyses became significant under a recessive or dominant model (results not shown). Post-hoc adjustment for possibly confounding effects of medications did not qualitatively affect primary SNP results (results not shown). A secondary logistic regression analysis of genetic effects on adverse events found no significant results, when adjusted for multiple tests (results not shown).

Discussion

The identification of pharmacogenetic markers that predict medication benefit or harm is a goal and prerequisite for the development of individualized therapy [36]. In this study, alleles at two EDN1 SNPs, G/A (IVS-4), and Lys198Asn, which commonly appeared in G-Lys or A-Asn haplotypes, showed a strong pharmacogenetic interaction with bucindolol therapy on time to first heart failure hospitalization or all-cause mortality. We believe this to be the first study to identify a haplotype associated with clinical response to a β-blocker in dilated cardiomyopathy. The observed effect was confined to the treated group, with no significant effect in the placebo group, consistent with a true pharmacogenetic effect where drug ‘exposure’ elicits different outcomes based on the genetic background. A ‘dose–response’ trend by haplotype was observed, with participants homozygous for the rare haplotype having the highest HRs as compared to the relative ‘protective’ effect of the common haplotype. A relative benefit of β-blocker therapy for the 56% of participants homozygous for the common haplotype identifies a large subpopulation, where β-blocker therapy seems most beneficial. Contrasted against this group are the 5.5% of participants, homozygous for the rare complementary haplotype, for whom the combined endpoint hazard rate was almost three times greater on bucindolol than on placebo.

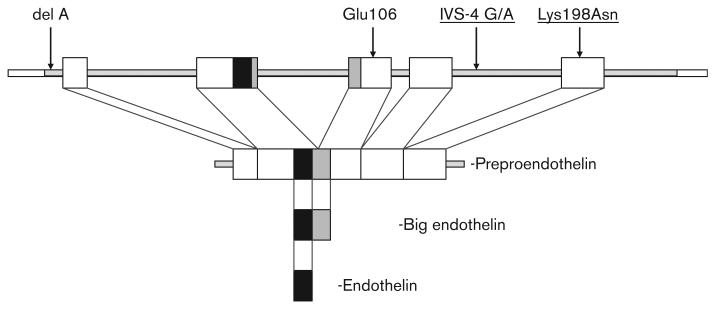

EDN1 G/A (IVS-4) and Lys198Asn are in tight linkage disequilibrium, which agrees with other published data and makes it impossible to distinguish which combination of SNPs is responsible for the observed effect. Strong linkage disequilibrium is also present between these SNPs and the rs1800543 variant in intron 3, which was not tested in this study [37]. Genotyping of G/A IVS-4, Lys198Asn, and rs1800543 largely define the same haplotype block extending from the beginning of intron 2 to exon 5. Three additional intronic SNPs not tested in this study (rs: 2070669, 1800543, 641347) and the Glu106 variant, which was not significant after multiple testing, also are contained in this haplotype block [37].

The G/A (IVS-4) variant is at position + 356 in intron 4 and does not localize to a known functional splicing or regulatory site (Fig. 3). It is located 6 bp downstream from an in silico predicted regulatory region using the ESPERR algorithm [38,39]. The SNP does not alter splicing in the GeneSplicer in-silico program [33], thus an obvious functional effect is lacking. Earlier studies of this SNP showed a modest influence on variability of left ventricular hypertrophy [16] and double heterozygosity of IVS-4 G/A and rs1800997 predicted lower big endothelin levels in one study of chronic heart failure [15]. The highly linked rs1800543 also shows no predicted effect on splicing.

Fig. 3.

Location of endothelin-1 (EDN1) polymorphisms studied. The genomic structure of the five exons (boxes) of the EDN1 gene is depicted (top) along with the four EDN1 polymorphisms analyzed. The Lys198Asn and intervening sequence (IVS)-4 G/A polymorphisms associated with bucindolol response are underlined. The Lys198Asn polymorphism is translated into the preproendothelin peptide, but is removed during processing into big endothelin.

The nonsynonymous change at position 198 where a basic, charged lysine is replaced with a smaller, polar asparagine residue may affect secondary protein structure by extending regional coiled structure (GOR IV and PSIPRED algorithms) [31,32]. It has been suggested that differences in preproendothelin levels or stability could explain biological differences between Asn198 and Lys198 as effects on mRNA levels were absent in one in-vitro study [40]. Serum EDN1 levels and big endothelin levels predict clinical heart failure phenotypes, and elevations correlate directly with heart failure severity and poorer prognosis and inversely with ejection fraction and cardiac index [41-43]. The differences in endothelin levels are mediated by levels of its precursor, big endothelin [41]. It is possible that the Asn198 variant subtly alters big endothelin levels, stability, or conversion to EDN1 by ECE. Compatible with this model are data from pregnant women and a separate hypertensive population where Asn198 alleles were predictive of higher serum endothelin levels [25,44].

Thus although an exact mechanism for the pharmacogenetic interaction observed in our data is not immediately apparent, earlier studies suggest an effect of variation in plasma endothelin levels, which could alter the host response to a β-adrenergic blocker such as bucindolol. Carriers of the rare haplotype (A IVS-4 and 198Asn) had a poorer outcome with bucindolol exposure. These participants are predicted to have higher circulating endothelin levels based on earlier studies [15,25,44] and could potentially be more sensitive to the blood pressure lowering effects of bucindolol although a precise mechanism remains speculative and will need to be clarified with future functional studies. It remains possible that another EDN1 variant in linkage disequilibrium with our haplotype mediates the observed effect.

Case–control studies have been widely used to test for genetic associations with disease status or outcome. While relatively efficient in terms of costs and study population recruitment, these approaches are limited by focusing on cross-sectional and nonprospectively obtained phenotypes and by difficulties in the selection of distinct samples of cases and controls. The potential confounding, phenotype misclassification and population heterogeneity can bias results toward either significance or nonsignificance [45-47]. Our pharmacogenetic study design in a well-implemented and monitored clinical trial focusing on a single clearly defined clinical population is substantially protected from these problems by the prospective nature of clinical data collection, and the randomization of all participants at study entry so that genotypes are independent of treatment assignment. This study supports the view that relationships between prospective outcome and genotype can be identified with modest sample sizes within the structure of a randomized clinical trial, and that this strategy may be superior to standard case–control designs that suffer from the aforementioned limitations. In that context, we suggest the initial use of primary genotype within-treatment analyses rather than genotype–treatment interaction tests or traditional subgroup analyses of treatment within genotype, for reasons described in the Methods. It is important to note that a positive finding from each type of analysis yields different scientific conclusions.

Although our findings are restricted to dilated cardiomyopathy patients with class III and IV heart failure, the potential implications of the high-risk haplotype are substantial. BEST was terminated early because of a loss of investigator equipoise at a time when the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality was not statistically significantly reduced in the bucindolol arm [29]. Our analysis, however, demonstrates genetic predictors of outcome, which identify a large subpopulation of patients who did benefit from bucindolol as compared against placebo. These data are preliminary and it is not clear whether these findings are replicable in other heart failure populations or to more selective β-blockers. The significant associations from this study will require replication in larger studies to provide evidence of a pharmacogenetic effect of an EDN1 haplotype. Future phase 3 and 4 clinical studies, which include provisions for DNA collection and genotyping will be poised to address these questions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

DNA samples and support for L.Z., J.C., P.L., and L.C.L. were supplied by the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST) DNA Bank. The BEST Clinical Trial is cosponsored by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program. This manuscript has been reviewed by the BEST trial sponsors for scientific content and consistency of data with earlier BEST publications. This study was supported by grants NIH (HL67915-01A1; HL69071-01; GM062628-05).

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The Pharmacogenetics and Genomics Journal Online (www.pharmacogeneticsandgenomics.com).

References

- 1.MERIT-HF Study Group Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF) Lancet. 1999;353:2001–2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed10376614?ordinalpos7&itool = EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed. Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_DefaultReportPanel. Pubmed_RVDocSum. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, Colucci WS, Fowler MB, Gilbert EM, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349–1355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packer M, Coats AJ, Fowler MB, Katus HA, Krum H, Mohacsi P, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1651–1658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson GR. Drug metabolism and variability among patients in drug response. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2211–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans WE, Relling MV. Moving towards individualized medicine with pharmacogenomics. Nature. 2004;429:464–468. doi: 10.1038/nature02626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinshilboum R. Inheritance and drug response. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:529–537. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liggett SB, Mialet-Perez J, Thaneemit-Chen S, Weber SA, Greene SM, Hodne D, et al. A polymorphism within a conserved beta(1)-adrenergic receptor motif alters cardiac function and beta-blocker response in human heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11288–11293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509937103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nambi P, Clozel M, Feuerstein G. Endothelin and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2001;6:335–340. doi: 10.1023/a:1011464510857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levin ER. Endothelins. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:356–363. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508103330607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyauchi T, Masaki T. Pathophysiology of endothelin in the cardiovascular system. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:391–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dzau VJ. The role of mechanical and humoral factors in growth regulation of vascular smooth muscle and cardiac myocytes. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1993;2:27–32. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue A, Yanagisawa M, Kimura S, Kasuya Y, Miyauchi T, Goto K, et al. The human endothelin family: three structurally and pharmacologically distinct isopeptides predicted by three separate genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2863–2867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens PA, Brown MJ. Genetic variability of the ET-1 and the ETA receptor genes in essential hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26(Suppl 3):S9–S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasku A, Spinarova L, Goldbergova M, Muzik J, Spinar J, Vitovec J, et al. The double heterozygote of two endothelin-1 gene polymorphisms (G8002A and −3A/−4A) is related to big endothelin levels in chronic heart failure. Exp Mol Pathol. 2002;73:230–233. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2002.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugada R, Kelsey W, Lechin M, Zhao G, Yu QT, Zoghbi W, et al. Role of candidate modifier genes on the phenotypic expression of hypertrophy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Investig Med. 1997;45:542–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krum H, Gu A, Wilshire-Clement M, Sackner-Bernstein J, Goldsmith R, Medina N, et al. Changes in plasma endothelin-1 levels reflect clinical response to beta-blockade in chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 1996;131:337–341. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spieker LE, Noll G, Ruschitzka FT, Luscher TF. Endothelin receptor antagonists in congestive heart failure: a new therapeutic principle for the future? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1493–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spieker LE, Luscher TF. Will endothelin receptor antagonists have a role in heart failure? Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:459–474. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannessi D, Del Ry S, Vitale RL. The role of endothelins and their receptors in heart failure. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43:111–126. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iemitsu M, Maeda S, Otsuki T, Sugawara J, Tanabe T, Jesmin S, et al. Polymorphism in endothelin-related genes limits exercise-induced decreases in arterial stiffness in older subjects. Hypertension. 2006;47:928–936. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217520.44176.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozak M, Izakovicova Holla L, Krivan L, Vaskuo A, Sepsi M, Semrad B, et al. Endothelin-1 gene polymorphism in patients with malignant arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:S92–S95. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000166228.80840.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin JJ, Nakura J, Wu Z, Yamamoto M, Abe M, Tabara Y, et al. Association of endothelin-1 gene variant with hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:163–167. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000043680.75107.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iglarz M, Benessiano J, Philip I, Vuillaumier-Barrot S, Lasocki S, Hvass U, et al. Preproendothelin-1 gene polymorphism is related to a change in vascular reactivity in the human mammary artery in vitro. Hypertension. 2002;39:209–213. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiret L, Poirier O, Hallet V, McDonagh TA, Morrison C, McMurray JJ, et al. The Lys198Asn polymorphism in the endothelin-1 gene is associated with blood pressure in overweight people. Hypertension. 1999;33:1169–1174. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.5.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann S, Schmidt-Petersen K, Pfeifer J, Perrot A, Bit-Avragim N, Eichhorn C, et al. A polymorphism in the endothelin-A receptor gene predicts survival in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1948–1953. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charron P, Tesson F, Poirier O, Nicaud V, Peuchmaurd M, Tiret L, et al. Identification of a genetic risk factor for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Involvement of a polymorphism in the endothelin receptor type A gene. CARDIGENE group. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:1587–1591. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicaud V, Poirier O, Behague I, Herrmann SM, Mallet C, Troesch A, et al. Polymorphisms of the endothelin-A and -B receptor genes in relation to blood pressure and myocardial infarction: the Etude Cas-Temoins sur l'Infarctus du Myocarde (ECTIM) Study. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:304–310. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial Investigators A trial of the beta-blocker bucindolol in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1659–1667. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442202. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed11386264?ordinalpos3&itool = EntrezSystem2. PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel. Pubmed_DefaultReportPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The BEST Steering Committee Design of the Beta-Blocker Evaluation Survival Trial (BEST) Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1220–1223. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garnier J, Gibrat JF, Robson B. GOR method for predicting protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:540–553. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DT. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pertea M, Lin X, Salzberg SL. GeneSplicer: a new computational method for splice site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1185–1190. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.5.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brookes ST, Whitely E, Egger M, Smith GD, Mulheran PA, Peters TJ. Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses; power and sample size for the interaction test. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westfall PH, Young SS. Resampling-based multiple testing. Wiley; New York: 1993. pp. 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cascorbi I, Paul M, Kroemer HK. Pharmacogenomics of heart failure – focus on drug disposition and action. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diefenbach K, Arjomand-Nahad F, Meisel C, Fietze I, Stangl K, Roots I, et al. Systematic analysis of sequence variability of the endothelin-1 gene: a prerequisite for association studies. Genet Test. 2006;10:163–168. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.10.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolbe D, Taylor J, Elnitski L, Eswara P, Li J, Miller W, et al. Regulatory potential scores from genome-wide three-way alignments of human, mouse, and rat. Genome Res. 2004;14:700–707. doi: 10.1101/gr.1976004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King DC, Taylor J, Elnitski L, Chiaromonte F, Miller W, Hardison RC. Evaluation of regulatory potential and conservation scores for detecting cis-regulatory modules in aligned mammalian genome sequences. Genome Res. 2005;15:1051–1060. doi: 10.1101/gr.3642605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castro MG, Rodriguez-Pascual F, Magan-Marchal N, Reguero JR, AlonsoMontes C, Moris C, et al. Screening of the endothelin1 gene (EDN1) in a cohort of patients with essential left ventricular hypertrophy. Ann Hum Genet. 2007;71:601–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei CM, Lerman A, Rodeheffer RJ, McGregor CG, Brandt RR, Wright S, et al. Endothelin in human congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1994;89:1580–1586. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMurray JJ, Ray SG, Abdullah I, Dargie HJ, Morton JJ. Plasma endothelin in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85:1374–1379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hiroe M, Hirata Y, Fujita N, Umezawa S, Ito H, Tsujino M, et al. Plasma endothelin-1 levels in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:1114–1115. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90511-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barden AE, Herbison CE, Beilin LJ, Michael CA, Walters BN, Van Bockxmeer FM. Association between the endothelin-1 gene Lys198Asn polymorphism blood pressure and plasma endothelin-1 levels in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancy. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1775–1782. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cordell HJ, Clayton DG. Genetic association studies. Lancet. 2005;366:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hattersley AT, McCarthy MI. What makes a good genetic association study? Lancet. 2005;366:1315–1323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newton-Cheh C, Hirschhorn JN. Genetic association studies of complex traits: design and analysis issues. Mutat Res. 2005;573:54–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.