Abstract

Epidemiological studies suggest that low vitamin D levels may increase the risk or severity of respiratory viral infections. In this study, we examined the effect of vitamin D on respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infected human airway epithelial cells. Airway epithelium converts 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (storage form) to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (active form). Active vitamin D, generated locally in tissues, is important for the non-skeletal actions of vitamin D including its effects on immune responses. We found that vitamin D induces IκBα, a NF-κB inhibitor, in airway epithelium and decreases RSV induction of NF-κB driven genes like interferon-β and CXCL10. We also found that exposing airway epithelial cells to vitamin D reduced induction of interferon stimulated proteins with important antiviral activity, e.g., MxA and ISG15. In contrast to RSV-induced gene expression, vitamin D had no effect on interferon signaling and isolated interferon induced gene expression. Inhibiting NF-κB with an adenovirus vector that expressed a non-degradable form of IκBα mimicked the effects of vitamin D. When the vitamin D receptor was silenced with siRNA the vitamin D effects were abolished. Most importantly we found that, in spite of inducing IκBα, and dampening chemokines and interferon-β, there was no increase in viral mRNA or protein or in viral replication. We conclude that vitamin D decreases the inflammatory response to viral infections in airway epithelium without jeopardizing viral clearance. This suggests that adequate vitamin D levels would contribute to reduced inflammation and less severe disease in RSV infected individuals.

Keywords: Human, Lung, Viral, Chemokines, Inflammation

Introduction

Vitamin D is increasingly recognized as a pluripotent hormone with functions that extend beyond its classical role in calcium homeostasis (1). Rapidly growing evidence from epidemiological and basic research studies reveals that vitamin D can modulate immune responses (2–4). Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent and has been associated both with increased risk of several inflammatory diseases (5–9) and with susceptibility to infections, including viral respiratory infections (10, 11). The localized tissue-specific generation of active vitamin D is thought to be a key component of non-classical vitamin D functions. In our previously published data, we showed that normal lung epithelium constitutively converts 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25D = storage form of vitamin D) to 1,25D-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25D = active form of vitamin D) and that the generation of active vitamin D is increased in the presence of viral infection (12).

The airway epithelium is the first line of defense during respiratory virus infection (13). Respiratory epithelium expresses Toll-like receptors (TLR) and Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors which sense viral RNA. Ligand engagement results in the activation of both nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) (14–16). The end result is amplification of host defense to microorganisms through secretion of antimicrobial peptides, chemokines and cytokines, and, in particular, type I interferons (13, 17). We have shown that vitamin D increases the toll-like receptor, co-receptor CD 14, and the antimicrobial peptide, cathelicidin, in airway epithelium (12). Type I interferons (IFNs) play a crucial role in defense against viruses. They mediate antiviral activity by triggering the expression of >100 IFN stimulated genes (ISGs), the products of which have diverse antiviral activities (18, 19).

Chemokines are a family of small molecules that induce chemotaxis of neutrophils, mononuclear cells, or lymphocytes. Chemokines can also stimulate leukocyte degranulation or release of inflammatory mediators (20). Chemokines thus play a pivotal role in orchestrating inflammation and have been found to be produced by an array of cells including epithelial cells (21). Production of chemokines can be either beneficial or detrimental to the host. Inflammation is an essential component of host defense, however, a too vigorous response against microbes or inflammation may be deleterious to the host, leading to impaired organ function. Vitamin D has been shown to inhibit production of inflammatory chemokines in animal models of inflammatory diseases like multiple sclerosis and type-1 diabetes (22–24).

The family of NF-κB transcriptional regulatory factors has a central role in coordinating the expression of a wide variety of genes that control immune responses. NF-κB proteins are present in the cytoplasm in association with inhibitory proteins (IκBs). IκBs are phosphorylated by IκB kinase following cell stimulation, and they are targeted for destruction by the ubiquitin/proteasome degradation pathway (25). The degradation of IκB allows NF-κB proteins to translocate to the nucleus, bind to their DNA binding sites (26), and activate a variety of genes, including cytokines and chemokines (27). Studies in various cell types, including dendritic cells (28–30), fibroblasts (31, 32), keratinocytes (33), pancreatic islet cells (23) and kidney cells (34) indicate that vitamin D dampens NF-κB signaling. Several mechanisms have been proposed, including vitamin D induced increase in IκBα (23, 32, 33), and/or interference with binding of NF-κB subunits, to promoter-regulatory areas (30, 31, 34).

Epidemiological studies suggest that low vitamin D levels are a risk factor for viral respiratory infections. However, vitamin D has been found to inhibit NF-κB signaling which could result in decreased viral clearance and/or lessened inflammatory responses via inhibition of type I IFN signaling and chemokines. The present study was undertaken to look at the effects of vitamin D on NF-κB signaling, especially as it relates to antiviral immunity in airway epithelium.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

1α 25-Dihydroxy Vitamin D3 was obtained from Calbiochem, San Diego, CA. Lactacystin was obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Interferon-β was purchased from PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, NJ.

Human Tracheo-Bronchial Epithelial Cells

Human tracheobronchial epithelial (hTBE) cells were obtained from the University of Iowa Cell and Tissue Core under a protocol approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. Epithelial cells were isolated from tracheal and bronchial mucosa by enzymatic dissociation and cultured in Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis (LHC)-8e medium on plates coated with collagen for study up to passage 10 as described previously (35). All experiments were conducted using cells from at least three different donors.

Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Cells at 80% confluency were infected with human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), strain A-2 (MOI 1-2). Viral stocks were obtained from Advanced Biotechnologies Inc (Columbia, MD). The initial stock (3×108 PFU/ml) was placed in aliquots and kept frozen at −135°F. The virus was never refrozen. GFP-RSV was a kind gift from Dr. Varga (University of Iowa).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous – 4PCR kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and quantity were assessed with Experion automated electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using the Experion RNA StdSens Analysis Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was considered adequate for use if the 28S/18S ratio was >1.2 and the RNA Quality Indicator (RQI) was >7. Total RNA (300 ng) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR reactions were performed using 2 μl cDNA and 48 μl master mix containing iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 15 pmol of forward primer and 15 pmol of reverse primer, in a CFX 96 Real Time System as follows: 3 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 55°C + plate read. The fluorescence signal generated with SYBR Green I DNA dye was measured during annealing steps. Specificity of the amplification was confirmed using melting curve analysis. Data were collected and recorded by CFX Manager Software and expressed as a function of threshold cycle (CT). The relative quantity of the gene of interest was then normalized to relative quantity of HPRT (ΔΔCT). The sample mRNA abundance was calculated by the formula 2−(ΔΔCT). Specific primer sets used are as follows (5′ to 3′):

CXCL10 GTCTGAATCCAGAATCGAAGGC (forward), TTGAGGGTTTGCTACAACATGGGC (reverse); HPRT GCAGACTTTGCTTTCCTTGG (forward), AAGCAGATGGCCACAGAACT (reverse); IFNβ TGGGAGGCTTGAATACTGCCTCAA (forward), TCCTTGGCCTTCAGGTAATGCAGA (reverse); IκBα AACCTGCAGCAGACTCCACT (forward), TCCTGAGCATTGACATCAGC (reverse); ISG15 CTGAGAGGCAGCGAACTCATCTTT (forward), AATCTTCTGGGTGATCTGCGCCTT (reverse); MXA GAAGCCCTGCAGAGAGAGAA (forward), AACTCGTGTCGGAGTCTGGT (reverse); RSV N-gene CAAGCCCAAAGCTGTGCTAAACCA (forward), AGACAGTGACTATGCGGTCTGCAA (reverse).

Gene specific primers were custom-synthesized and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Iowa City, IA) based on design using gene-specific nucleotide sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence databases and PrimerQuest web interface (Integrated DNA Technologies).

Cellular Protein

Whole cell protein extracts were prepared by lysis of cell monolayers in 200 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40), a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA), and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (#524625 Calbiochem). The lysates were sonicated for 20 s and kept at 4 °C for 30 min. After a 5 min centrifugation (14.000 rpm @ 4 °C) the supernatant was saved as whole cell lysate.

Cytosolic and nuclear protein extracts were prepared by lysis of cells in 400 μl of lysis buffer (10mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA). The lysates were incubated on ice for 15 min, 25 μl of 10% Nonidet P-40 was added, and vigorous mixing ensued. After a 30 s centrifugation (14.000 rpm @ 4 °C), the supernatant was saved as the cytosolic fraction. The pelleted nuclei were resuspended in 50 μl of extraction buffer (50mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 50mM KCl, 300mM NaCl, 0.1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) and incubated on ice for 20 min. After a 5 min centrifugation (14.000 rpm @ 4 °C) the supernatant was saved as nuclear fraction. Protein determinations were made using a protein measurement kit (Bradford Protein Assay, #500-0006) from BioRad. Extracts were stored at −70 °C.

Primary Antibodies

Primary antibodies were obtained from the following: IκBα; Santa Cruz Biotechnology #203 (Santa Cruz, CA), HDAC2; Santa Cruz #7899, ISG15; R&D systems #4845 (Minneapolis, MN), MXA; BacLab #CH-4302 (Muttenz, Switzerland), p65; Santa Cruz #109, total STAT1; Santa Cruz #346, phospho STAT1 tyrosine-701; Cell Signaling Technology #9171 (Beverly, MA), phospho STAT1 serine-727; Cell Signaling #9177, RSV all antigen; Biodesign International #B65860G (Saco ME) VDR; Santa Crus #13133, and IRF-3 Cell Signaling #4962.

Immunoblot Analysis

Protein (25–30 μg of whole cell or 8–15 μg nuclear) was mixed 1:1 with 2× sample buffer (20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.05% bromophenol blue and 1.25M Tris pH 6.8), loaded onto a 12% or 15% (ISG15) SDS-PAGE gel, and run at 150V for 90 min. Cell proteins were transferred to Immuno-Blot PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad) with a Bio-Rad semidry transfer system, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PVDF was then incubated with primary antibody (dilutions 1:500 to 1:1000) in 5% milk in TTBS (tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) overnight. The blots were washed × 3 with TTBS and incubated for 1 h with horseradish-peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary anti-IgG antibody (dilution 1:2000 to 1:20.000). The blots were washed again × 3 with TTBS, and immunoreactive bands were developed using a chemiluminescent substrate, ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). An autoradiograph was obtained, with exposure times of 10 s to 2 min. Equal loading of proteins was confirmed with β-actin (Abcam #8226) (primary antibody dilution 1:20.000 and secondary 1:40.000).

Secreted Proteins

Supernatants were collected and frozen at −70 °C. CXCL 10 concentrations were determined using DuoSet ELISA kits from R&D systems (# DY266) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA Interference

Control siRNA (Santa Cruz #44230) or target-specific 19–25 nt siRNA designed to knock down VDR gene expression (Santa Cruz #106692) was transfected into hTBE cells at a final concentration of 50 nM using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Transfection mixtures were assembled as previously described (36). Cells were incubated with 200 μl of transfection mixture and 2 ml of antibiotic-free medium for 16–18 h. Transfection efficiency was assessed with using a fluorescent control siRNA (Santa Cruz #36869). Knock down of VDR was confirmed with real time quantitative PCR and Western Blotting.

NF-κB Pathway Inhibition

Inhibition of NF-κB dependent signaling was accomplished by infecting hTBE cells with a recombinant adenoviral vector (MOI=10) that expresses a dominant-negative mutant form (non-degradable) of IκBα or the control vector BglII, as previously described (37). An adenovirus vector expressing GFP was used to assess the level of epithelial cell transgene expression.

Statistical analysis

When two groups were compared, we used two tailed Student’s t test. To compare three or more groups we used repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s method to control for multiple comparisons. When treatments were being compared with control but not each other Dunnett’s test was used to correct for multiple comparisons. Data is presented as mean +/− SEM. P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. These methods were performed using GraphPad Prizm 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Vitamin D induces the NF-κB inhibitory protein IκBα in airway epithelium

To determine the effects of vitamin D on NF-κB signaling we examined the effect of vitamin D on the NF-κB inhibitory protein IκBα. In other systems, vitamin D increases the expression of IκBα, therefore, we hypothesized that this was also true for airway epithelium (23, 32, 33). To test this hypothesis, hTBE cells were treated with 1,25D for 24 h and IκBα mRNA was evaluated with quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Treatment with vitamin D led to a statistically significant increase in IκBα mRNA (Fig. 1A). There was no change in mRNA half life suggesting an effect of vitamin D on transcription (data not shown).

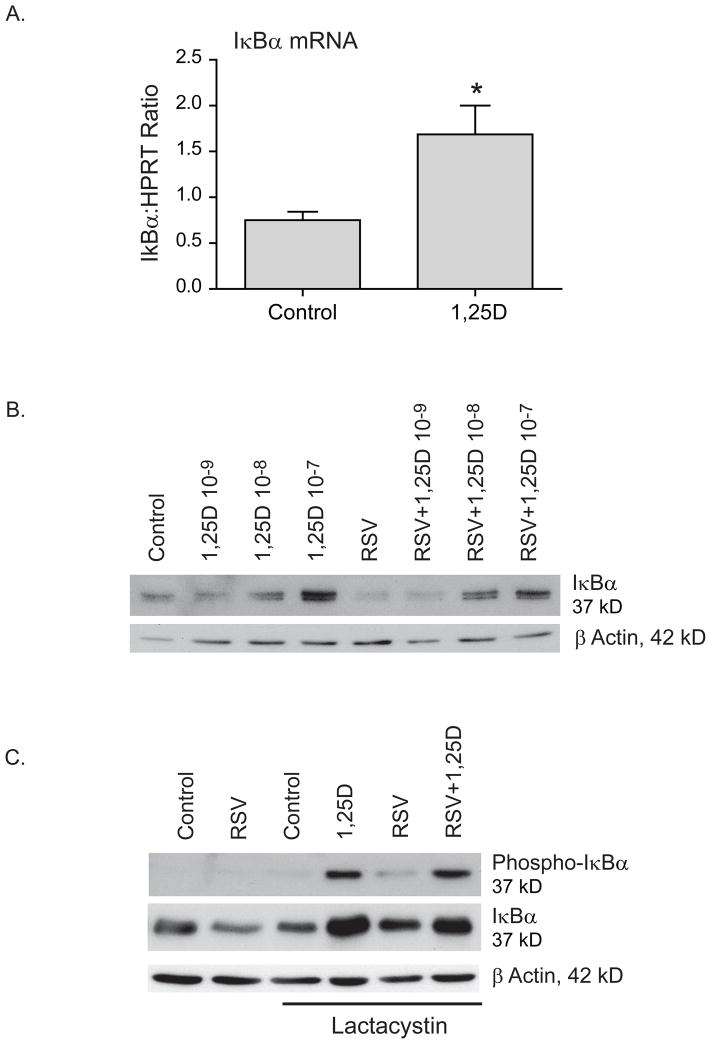

FIGURE 1.

Vitamin D increases expression of the NF-κB inhibitory protein IκBα. A. hTBE cells were treated with 1,25D 10−7 for 36 h and IκBα mRNA measured by qRT-PCR. Vitamin D increases IκBα mRNA. B. hTBE cells pretreated with increasing doses of 1,25D for 16–18 h and then infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 24 h. Vitamin D increases IκBα protein in a dose dependent manner. Less IκBα protein is seen in RSV infected cells compared with non-infected cells. C. hTBE cells pretreated with 1,25D 10−7 followed by infection with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 24 h. The proteasome inhibitor lactacystin (10 μM) was added for the last 3 h of the experiment. 1,25D increased both total and phosphorylated IκBα suggesting that induction of IκBα by 1,25D is due to increased production of IκBα rather than inhibition of its degradation. Paired Student t-test. * p<0.05 when c/w control.

We proceeded to look at IκBα protein levels and found that vitamin D increases IκBα protein in a dose dependant manner. When we evaluated a viral model, cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) for 24 h had decreased IκBα protein levels consistent with RSV induced degradation of IκBα. When cells were pretreated with increasing doses of 1,25D, prior to infection with RSV, we saw a dose dependent increase in IκBα levels in RSV infected and non-infected cells (Fig. 1B). To investigate whether the increase in protein levels was due to changes in IκBα phosphorylation and degradation we pretreated airway epithelial cells with 1,25D and infected them with RSV for 24 h with and without the proteasome inhibitor (lactacystin) for the last 3 h of the experiment. We found that, in the presence of a proteasome inhibitor, 1,25D increased both total and phosphorylated IκBα in the presence and absence of RSV infection (Fig. 1C). This data, combined, indicates that in airway epithelium vitamin D increases levels of IκBα, a well established inhibitor of NF-κB signaling, by increasing mRNA transcription and protein synthesis. The proteasome inhibitor data suggests that the increase in IκBα with vitamin D exposure is due to increased production and not increased stability.

Vitamin D suppresses IFNβ and interferon stimulated genes in hTBE cells infected with RSV

Infected airway epithelium utilizes TLRs and the RNA helicase, retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), to detect and respond to RSV infection (38–42). Activation of those signaling pathways leads to activation of the transcription factors NF-κB and IRFs (43). Following RSV infection, NF-κB translocates into the nucleus and turns on target genes including IFNβ (type I interferon) and several chemokines that are essential for host defense against viral infection (44, 45). Having established that vitamin D inhibits NF-κB signaling in airway epithelium, we next asked whether 1,25D limits expression of host defense molecules driven by NF-κB. First, we wanted to establish at which time point RSV-induced gene expression was at maximum. hTBE cells were treated with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 3,6,16 or 24 h and expression of IFNβ, STAT1, interferon stimulated genes (ISGs), and chemokines were examined (Fig. 2A). This revealed significant induction at 16 h with maximum at 24 h. We then went on to evaluate the effects of vitamin D on virally induced genes at 24 h. IFNβ is essential to host response against viral infections (46). The gene coding for IFNβ has a NF-κB site in its promoter which, along with ATF-2/c-jun and IRF-3/IRF-7 sites, comprises the enhanceosome, required for transcriptional activation of the IFNβ gene. In turn, IFNβ activates STAT1 and STAT2. hTBE cells were pretreated with 1,25D followed by 24 h of infection with RSV (MOI 1-2). IFNβ mRNA and STAT1 activation were measured with qRT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. Treatment with 1,25D resulted in significant reduction of IFNβ mRNA and of IFNβ induced STAT1 protein and STAT1 translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 2B). Activation of STAT1 and STAT2 leads to the formation of the transcription complex interferon stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). ISGF3 binds to interferon stimulated response elements (ISRE) in ISGs and induces their expression.

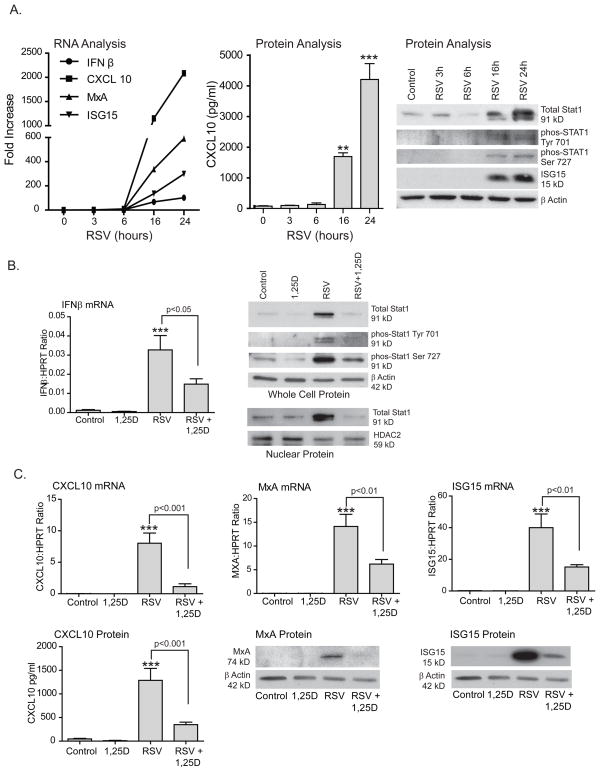

FIGURE 2.

Vitamin D decreases RSV induction of IFNβ and interferon stimulated genes. A. hTBE cells were infected with RSV for 3,6,16 and 24 h. Induction of IFNβ, ISGs, and chemokines was evaluated using qRT-PCR, ELISA and Western blot. Maximum induction was observed at 24 h. B. hTBE cells were pretreated with 1,25D 10−7 for 16–18 h and then infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 24 h. INFβ mRNA was quantified with qRT-PCR. Total STAT1, phosphorylated STAT1 at tyrosine 701 and serine 927 and nuclear STAT1 were observed using Western blot. Vitamin D decreased RSV induced IFNβ mRNA and RSV induction of STAT1 and its nuclear translocation. C. hTBE cells were pretreated with vitamin D and infected with RSV as in B. CXCL10, MxA and ISG15 mRNA were evaluated with qRT-PCR. CXCL10 protein was measured with ELISA and MxA and ISG15 protein by Western blot. Vitamin D decreased RSV induction of the chemokine CXCL10 and, to a lesser extent, the antiviral effectors MxA and ISG15. ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for comparisons with control (A) and Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons (B,C). ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 when c/w control.

We next determined the role of vitamin D in expression of interferon stimulated genes with and without known NF-κB sites in their promoters. CXCL10 (IP-10) is a chemokine that is induced by RSV infection (44, 47, 48) and has both ISRE and NF-κB sites in its promoter (49). Myxovirus resistance A (MxA) and IFN-stimulated protein of 15kDa (ISG15), on the other hand, are ISGs that directly inhibit viral production (50) and have ISRE sites in their promoters but not functional NF-κB sites (51–53). As before, we pretreated hTBE cells with 1,25D, followed by RSV infection, and looked at gene transcription and protein levels. Treatment with 1,25D resulted in decreased levels of both chemokines and antiviral effectors (Fig. 2C). The suppression in transcription was more pronounced for CXCL10 (ISRE and NF-κB sites) with 86% reduction in CXCL10 mRNA, than in the antiviral effectors (ISRE site only), where 56% reduction of MxA and 62% reduction in ISG15 was observed (Fig. 2C). This data indicates that 1,25D does modulate IFNβ and ISGs in airway epithelium infected with RSV. These findings raise the question: is vitamin D directly inhibiting both NF-κB and STAT signaling or is it alternatively having a direct effect on only NF-κB with subsequent suppression of NF-κB driven interferon production and STAT activation?

The effects of vitamin D on antiviral effectors occur at the level of NF-κB

We proceeded to determine whether vitamin D could be effecting no only activation of NF-κB but also activation of IRF-3. Recognition of viral RNA by either RIG-I like receptors or TLR results in activation of both NF-κB and IRF-3. If the effects of vitamin D were at the level of dsRNA sensing, one would expect expression of both transcription factors to be decreased. IRF-3 is a latent transcription factor that is activated by phosphorylation by kinases that are activated in response to viral dsRNA (54). This results in the formation of IRF-3 dimers that translocate to the nucleus and bind to promoter areas. IRF-3 activation has been shown to be rapid (< 6 hours) in RSV infection (38). To investigate whether the vitamin D effects could be explained by effects on IRF-3, we looked at translocation of IRF-3 to the nucleus. hTBE cells were infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 1, 3 or 8 h in the presence or absence of vitamin D. Nuclear translocation of IRF-3 was evaluated with Western blot (Fig. 3A). Vitamin D did not suppress IRF-3 translocation to the nucleus, but on the contrary, may have even increased it.

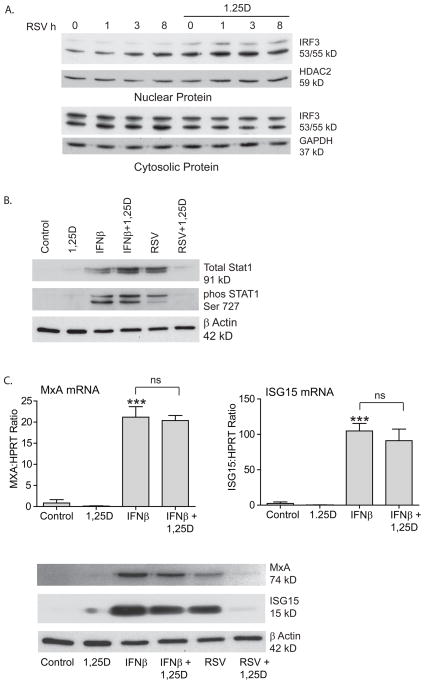

FIGURE 3.

The effects of vitamin D occur at the level of NF-κB. A. hTBE cells infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 1, 3 or 8 h in the presence or absence of pretreatment with 1,25D 10−7M. Western blot for nuclear and cytosolic IRF-3. Vitamin D does not decrease nuclear localization of IRF-3. B. hTBE cells pretreated with 1,25D 10−7M for 16–18 h and then stimulated with IFNβ (1000U) or infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 24 h. STAT1 induction was looked at with Western blot. Vitamin D does not effect IFNβ induced STAT1. C. hTBE cells treated as in B. and expression of MxA and ISG15 mRNA and protein were evaluated with qRT-PCR and Western blot, respectively. Vitamin D did not influence IFNβ induced MxA or ISG15.

Activation of NF-κB leads to induction of IFNβ. The most likely explanation of our data is that suppression of NF-kB by vitamin D leads to production of less IFNβ, which is dependent on this transcription factor for its expression. However, if the effects of vitamin D were downstream of IFNβ, then one would expect vitamin D to have the same effects on STAT1 and ISGs induction by IFNβ itself and RSV. To determine this, hTBE cells were treated with IFNβ (1000 U) or RSV (MOI 1-2) for 24 h in the presence or absence of vitamin D. As expected, both IFNβ and RSV increased expression and activation of STAT1. In contrast to RSV induced STAT1, vitamin D had no effects on IFNβ induced STAT1 (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, unlike RSV induced antiviral effectors, vitamin D had no effects on IFNβ induced MxA or ISG15 (Fig. 3C). This suggests that vitamin D does not effect interferon signaling downstream of IFNβ.

These results, combined, suggest that the effects of vitamin D are occurring at the level of NFκB.

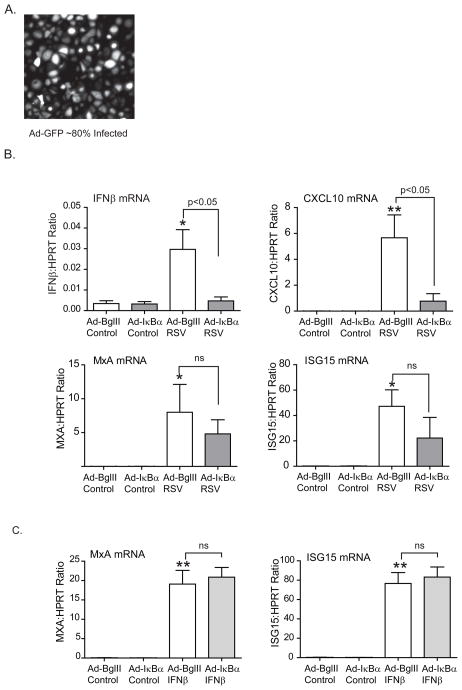

Overexpressing IkBa mimics vitamin D effects on airway epithelial responses

To further support our hypothesis that 1,25D is modulating airway epithelial response to viral infection by inhibiting NF-κB, we introduced a recombinant adenoviral vector expressing a dominant-negative mutant form (non-degradable) of IκBα (55). We hypothesized that inhibiting NF-κB with the adenovirus vector would mimic the effects of 1,25D. First we assessed the level of epithelial cell transgene expression, by using an adenovirus vector expressing GFP, and found that about 80% of the cells expressed the vector (Fig. 4A). hTBE cells were subsequently infected with an adenovirus containing the non-degradable IκBα (AdIκBα S32/36) or an empty vector BglII (AdBglll). Briefly hTBE cells were incubated with adenovirus vector (MOI=10) for 2 h followed by change of media. Cells were infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) 24 h later. We found that inhibiting NF-κB with the AdIκBα mutant resulted in a significant decrease in RSV induction of IFNβ and CXCL10 with a less prominent decrease in MxA and ISG15 (Fig. 4B). As expected, the AdIκBα did not affect the expression of MxA or ISG15 when induced by IFNβ (Fig. 4C). This data shows that 1,25D has the same effects on IFNβ and interferon driven genes during RSV infection as overexpression of the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα.

FIGURE 4.

Overexpressing IκBα mimics vitamin D effects. A. hTBE cells were infected with GFP labelled adenovirus vector (MOI 10) for 24 h and transgene expression assessed with fluorescent microscopy. About 80% of the cells were found to express the GFP labelled adenovirus vector. B. and C. hTBE cells were infected with either empty adenovirus vector or an adenovirus vector overexpressing IκBα (MOI 10) for 24 h and then infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) or stimulated with IFNβ (1000U) for 24 h. IFNβ, CXCL10, MxA and ISG15 mRNA was quantified using qRT-PCR. Like 1,25D, the AdIκBα vector significantly reduced RSV induction of IFNβ and CXCL10. There was a trend towards a decrease in the RSV induced antiviral effectors, MxA and ISG15, which did not reach statistical significance. Like vitamin D, the AdIκBα vector had no effects on IFNβ induced MxA and ISG15. ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 when c/w control.

Silencing the Vitamin D Receptor abolishes vitamin D effects on airway epithelial responses to RSV

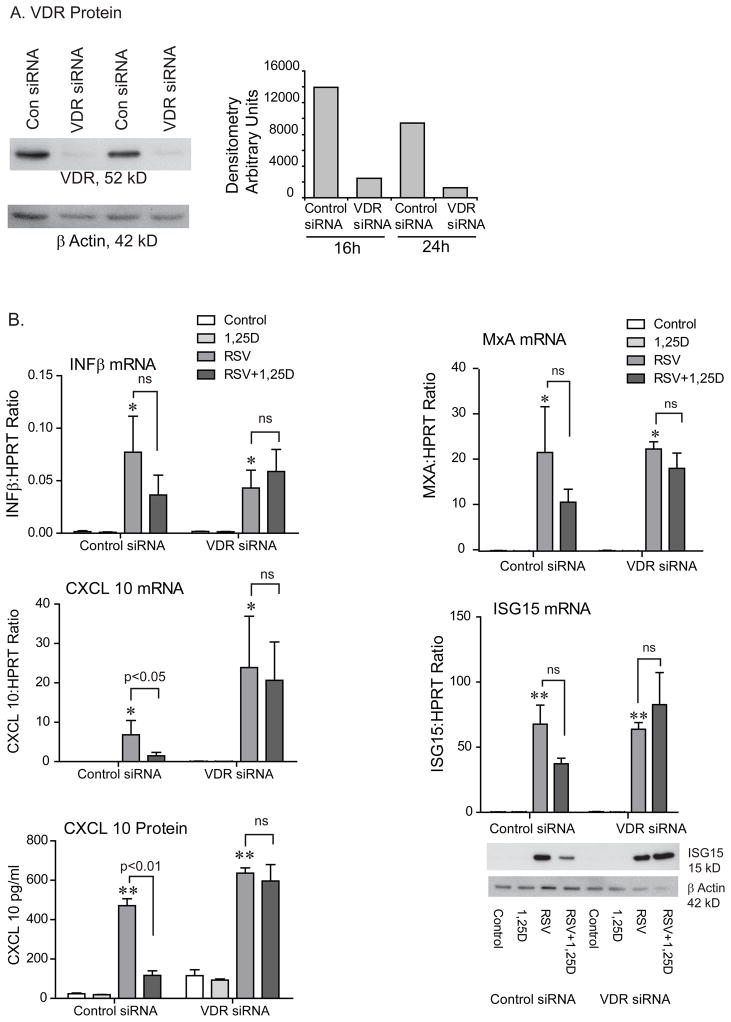

The biological effects of vitamin D are achieved through regulation of gene expression mediated by the vitamin D receptor (VDR) (56). VDR is a transcription factor and it dimerizes with the retinoic X receptor (RXR) upon ligand binding (57). This complex binds to vitamin D responsive elements (VDREs) within the promoter regions of vitamin D responsive genes (58). In order to confirm that our findings are directly due to 1,25D, we next explored whether silencing the VDR would reverse the vitamin D effects. hTBE cells were transfected with control siRNA or VDR siRNA. Transfection efficiency was tested using fluorescent control siRNA. Fluorescent microscopy indicated > 90% transfection efficiency (data not shown). Knock down of the VDR was confirmed with Western blotting (Fig. 5A). hTBE cells were pretreated with 1,25D followed by infection with RSV (MOI=1-2) for 24 h. Expression of IFNβ and ISGs was evaluated. When cells were transfected with control siRNA, vitamin D reduced RSV induced expression of IFNβ, chemokines, and antiviral effectors as shown previously in non-transfected cells. When VDR expression was silenced, vitamin D no longer had immunomodulatory effects (Fig. 5B). This data, combined, further supports that vitamin D modulates the inflammatory response to RSV by dampening induction of IFNβ and ISGs.

FIGURE 5.

Silencing the vitamin D receptor abolishes the effects of vitamin D on RSV induced IFNβ, chemokines, and interferon stimulated genes. A. hTBE cells were transfected with control siRNA or VDR siRNA for 16 or 24 h and VDR protein looked at with Western blot. The VDR siRNA successfully knocked down the VDR. B. hTBE cells were transfected with control siRNA or VDR siRNA for 24 h, pretreated with 1,25D for 16–18 h, and then infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) for 24 h. IFNβ, CXCL10, MxA and ISG15 mRNA were evaluated with qRT-PCR, CXCL10 protein with ELISA, and ISG15 protein with Western blot. Vitamin D reduced the expression of IFNβ, CXCL10, MxA and ISG15 in cells transfected with control siRNA, but had no effects in cells transfected with VDR siRNA. ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 when c/w control.

Vitamin D dose not effect viral replication

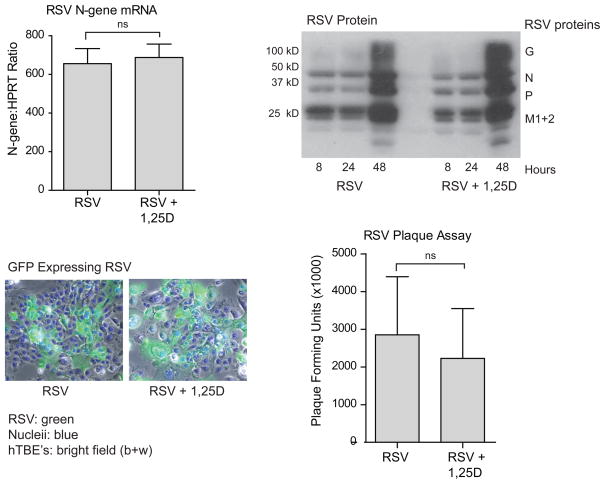

Interferon-β and interferon driven genes are central in host defense against viral infection. Based on our findings, vitamin D decreases expression of IFNβ and interferon driven genes by increasing IκBα and, thus, inhibits the canonical NF-κB pathway. This raises the concern that viral replication may be increased in the presence of 1,25D. Consequently, we infected hTBE cells with RSV in the presence or absence of 1,25D and looked at markers of viral quantity and replication. Expression of viral mRNA (N-gene) was measured by RT-PCR. RSV viral proteins were quantified by Western blotting (anti-RSV, all antigen). Viral titers were measured by standard plaque assay, as previously described (59). Lastly, cells were infected with GFP-labeled RSV, fixed with formalin, and viewed with a light and fluorescent microscope. All four modalities suggest that vitamin D does not alter viral replication (Fig. 6). This data shows that in spite of inhibition of IFNβ, and interferon stimulated genes, viral replication is not increased in the presence of 1,25D.

FIGURE 6.

Vitamin D does not jeopardize viral clearance. hTBE cells were infected with RSV (MOI 1-2) with or without pretreatment with 1,25D 10−7 M for 16–18 h. Viral quantity and viral replication was analyzed by RT-PCR, Western blot, light microscopy of GFP-tagged RSV (blue=Dapi nuclear stain) and plaque assay. Vitamin D had no effects on the quantity or replication of RSV. Unpaired Student t test.

Discussion

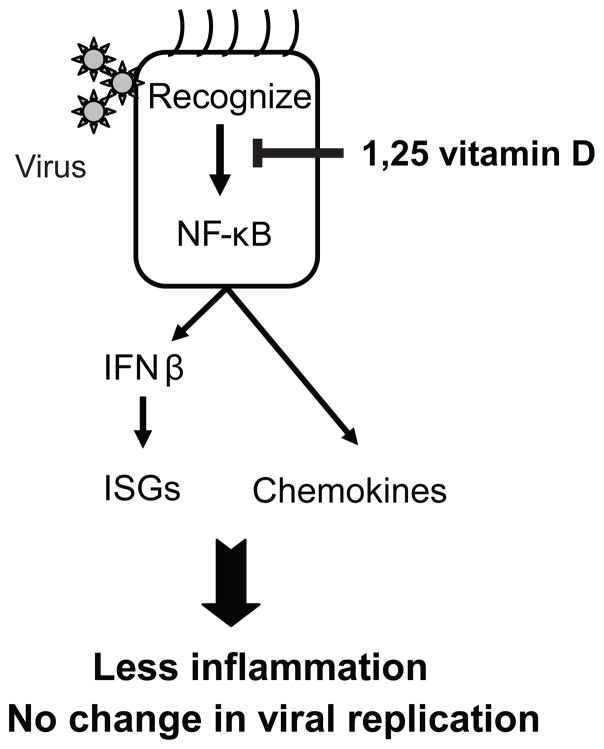

We have shown that vitamin D modulates NF-κB signaling in primary airway epithelial cells. Furthermore, we have found that even though vitamin D dampens expression of both chemokines and interferon driven genes, whose role is to limit the spread of a virus, viral load is not increased in the presence of vitamin D. This indicates that vitamin D may dampen the inflammatory response to viruses without negatively affecting viral replication (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Vitamin D decreases RSV induction of NF-κB-linked chemokines and cytokines in airway epithelium while maintaining the antiviral state. Respiratory epithelium recognizes viruses via pattern recognition receptors. Ligand engagement results in activation of NF-κB and NF-κB linked genes including IFNβ and chemokines. Vitamin D modulates the airway epithelial responses to RSV by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. In spite of dampening the innate antiviral response, vitamin D does not jeopardize viral clearance.

Airway epithelium serves as the first line host defense system against respiratory viral infection. In addition to forming a mechanical barrier, the airway epithelium detects viruses (via pattern recognition receptors) and initiates the host immunological response. Stimulation of NF-κB dependent gene transcription is a central aspect of inflammatory activation by pattern recognition receptors (60). The NF-κB pathway in airway epithelial cells is critical for generation of lung inflammation in response to local or systemic stimuli (61). The epithelial response to viral infections includes the production and secretion of chemokines, type I interferons (IFNβ), and liberation of antimicrobial peptides (17, 62, 63).

Several epidemiological studies have found an association between low vitamin D levels and respiratory infections (10, 11). It is well established that vitamin D modulates both innate and adaptive immune responses (3, 64). Vitamin D has been found to induce the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin in several cell types including airway epithelium (12, 65, 66). Animal studies suggest that vitamin D may dampen production of chemokines. In a mouse model of multiple sclerosis, vitamin D was found to reverse experimental autoimmune encephalitis by inhibiting synthesis of chemokines (22). Similar effects were found by two different groups using a mouse model for diabetes. Nonobese diabetic mice treated with vitamin D were found to have a decrease in pancreatic islet chemokine expression, which was accompanied by less insulitis and inhibition of type 1 diabetes development (23, 24). To our knowledge, this study is the first study to look at the effects of vitamin D on host defense against viral infection.

Vitamin D has been found to regulate NF-κB activity by increasing IκBα levels and/or decreasing DNA binding of NF-κB in keratinocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages, and kidney cells (32–34, 67, 68). Furthermore, two studies, using mouse models have linked NF-κB inhibition by vitamin D analogs with down-regulation of chemokines and inhibition of inflammation (23, 69). Using a mouse model of type 1 diabetes, Giarratana et al., found that a vitamin D analog up-regulated IκBα, and decreased in vivo and in vitro proinflammatory chemokine production by pancreatic islet cells. This resulted in the inhibition of T cell recruitment into pancreatic islets and type 1 diabetes development. In a mouse model of obstructive nephropathy, Tan et al., showed that paricalcitol, a vitamin D analog, reduced expression of chemokines and inhibited inflammatory cell infiltration in the obstructed kidney via VDR-mediated sequestration of NF-κB signaling. Our study is the first study to investigate the effects of vitamin D on NF-κB signaling in airway epithelium.

The airway epithelium is the major site of RSV infection and plays an important role in initiating antiviral and inflammatory response against the virus. Although a number of cell types secrete chemokines in inflamed tissue, a body of evidence supports a central role for the airway epithelium as an important initiator and modifier of pulmonary inflammation (44, 70). This is particularly true for RSV since the virus productively replicates only in the respiratory mucosa. Studies have shown that RSV is among the most potent biologic stimuli to induce chemokine production by respiratory epithelial cells, a process that is largely controlled by activation of NF-κB (71–75). Chemokines can be beneficial or detrimental to the host. Recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells is an essential component of host defense, however, too vigorous response against microbes may be deleterious leading to impaired organ function and potential mortality. Inflammatory chemokines have indeed been implicated as a contributor to the pathogenesis and severity of RSV infection (76–79). Therefore modulating RSV-induced chemokines may have the potential to prevent excessive inflammation. Attempts to find effective antiinflammatory therapies for this condition have been largely unsuccessful thus far. Several clinical trials have looked at using corticosteroids, but the results have not been consistent (80). Haeberle et al., treated RSV infected mice with perflubron (inserting it into the lungs) and found reduction in lung inflammation associated with inhibition of chemokine expression and NF-κB (75). Vitamin D provides a novel treatment option that may reduce lung inflammation and disease severity in RSV infection.

If vitamin D suppresses IFNβ induction and, subsequently, interferon driven genes which have diverse antiviral activities, then how is the antiviral state maintained? One possibility is that the suppression of interferon beta and its products is insignificant and sufficient amounts of antiviral effectors remain to successfully limit viral replication and spread. Another possibility is that induction of antimicrobial peptides, with antiviral activity, by vitamin D counteracts the reduction in interferon driven antiviral genes. We have shown that vitamin D induces cathelicidin in airway epithelium (12). Others have found that vitamin D increases beta defensin-2 (66) which was recently found to have antiviral activity against RSV (81).

Here we show in an in vitro model of primary human airway epithelial cells that even though 1,25D decreases viral (RSV) induction of chemokines and IFNβ, and subsequently interferon driven genes, there is no increase in viral replication. Controlling the inflammatory response to RSV viral infection, while maintaining antiviral activity, may result in decreased disease severity and consequently in decreased morbidity and mortality from this common infection. Vitamin D is safe, cheap, easily available, and could prove to be an effective therapeutic strategy, however, clinical studies are needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the cell and culture core at the University of Iowa for providing us with primary human airway epithelial cells. We thank Dr. Steve Varga for providing the GFP-labelled RSV and Dr. Dwight Look for providing us with the MxA antibody.

This manuscript was supported by KL2 RR024980, R01 HL079901, NIH RO1 HL077431, NIH RO1 HL073967, VA Merit Review grant, and NIH T32 HL007638.

The abbreviations used are

- 1,25D

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- hTBE

human tracheobronchial epithelial

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- ISG

interferon stimulated gene

- IRF

interferon regulatory factor

- ISRE

interferon stimulated response element

- ISGF3

interferon stimulated gene factor 3

- MxA

myxovirus resistance A

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams JS, Hewison M. Unexpected actions of vitamin D: new perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nature clinical practice. 2008;4:80–90. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nature reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White JH. Vitamin D signaling, infectious diseases, and regulation of innate immunity. Infection and immunity. 2008;76:3837–3843. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00353-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponsonby AL, Pezic A, Ellis J, Morley R, Cameron F, Carlin J, Dwyer T. Variation in associations between allelic variants of the vitamin D receptor gene and onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus by ambient winter ultraviolet radiation levels: a meta-regression analysis. American journal of epidemiology. 2008;168:358–365. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litonjua AA, Weiss ST. Is vitamin D deficiency to blame for the asthma epidemic? The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;120:1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, Fear N, Price A, Carpenter L, van Blankenstein M. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD) Gut. 1996;39:690–697. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.5.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnenberg A, McCarty DJ, Jacobsen SJ. Geographic variation of inflammatory bowel disease within the United States. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:143–149. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90594-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munger KL, Levin LI, Hollis BW, Howard NS, Ascherio A. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of multiple sclerosis. Jama. 2006;296:2832–2838. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannell JJ, Zasloff M, Garland CF, Scragg R, Giovannucci E. On the epidemiology of influenza. Virology journal. 2008;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA., Jr Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:384–390. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansdottir S, Monick MM, Hinde SL, Lovan N, Look DC, Hunninghake GW. Respiratory epithelial cells convert inactive vitamin D to its active form: potential effects on host defense. J Immunol. 2008;181:7090–7099. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt PG, Strickland DH, Wikstrom ME, Jahnsen FL. Regulation of immunological homeostasis in the respiratory tract. Nature reviews. 2008;8:142–152. doi: 10.1038/nri2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basu S, Fenton MJ. Toll-like receptors: function and roles in lung disease. American journal of physiology. 2004;286:L887–892. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00323.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saito T, Gale M., Jr Differential recognition of double-stranded RNA by RIG-I-like receptors in antiviral immunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:1523–1527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Function of RIG-I-like receptors in antiviral innate immunity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:15315–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartlett JA, Fischer AJ, McCray PB., Jr Innate immune functions of the airway epithelium. Contributions to microbiology. 2008;15:147–163. doi: 10.1159/000136349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PL, Lombardi G, Foster GR. Type I interferons and the innate immune response--more than just antiviral cytokines. Molecular immunology. 2005;42:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiscott J. Triggering the innate antiviral response through IRF-3 activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:15325–15329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay CR. Chemokines: immunology’s high impact factors. Nature immunology. 2001;2:95–101. doi: 10.1038/84298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strieter RM, Standiford TJ, Huffnagle GB, Colletti LM, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL. “The good, the bad, and the ugly.” The role of chemokines in models of human disease. J Immunol. 1996;156:3583–3586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen LB, Nashold FE, Spach KM, Hayes CE. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 reverses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting chemokine synthesis and monocyte trafficking. Journal of neuroscience research. 2007;85:2480–2490. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giarratana N, Penna G, Amuchastegui S, Mariani R, Daniel KC, Adorini L. A vitamin D analog down-regulates proinflammatory chemokine production by pancreatic islets inhibiting T cell recruitment and type 1 diabetes development. J Immunol. 2004;173:2280–2287. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gysemans CA, Cardozo AK, Callewaert H, Giulietti A, Hulshagen L, Bouillon R, Eizirik DL, Mathieu C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates expression of chemokines and cytokines in pancreatic islets: implications for prevention of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1956–1964. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Li J, Young DB, Barbosa M, Mann M, Manning A, Rao A. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF-kappaB activation. Science (New York, NY) 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, I, Verma M. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nature reviews. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blackwell TS, Christman JW. The role of nuclear factor-kappa B in cytokine gene regulation. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 1997;17:3–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.1.f132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong X, Craig T, Xing N, Bachman LA, Paya CV, Weih F, McKean DJ, Kumar R, Griffin MD. Direct transcriptional regulation of RelB by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogs: physiologic and therapeutic implications for dendritic cell function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:49378–49385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong X, Lutz W, Schroeder TM, Bachman LA, Westendorf JJ, Kumar R, Griffin MD. Regulation of relB in dendritic cells by means of modulated association of vitamin D receptor and histone deacetylase 3 with the promoter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:16007–16012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506516102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Ambrosio D, Cippitelli M, Cocciolo MG, Mazzeo D, Di Lucia P, Lang R, Sinigaglia F, Panina-Bordignon P. Inhibition of IL-12 production by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Involvement of NF-kappaB downregulation in transcriptional repression of the p40 gene. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;101:252–262. doi: 10.1172/JCI1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harant H, Wolff B, Lindley IJ. 1Alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 decreases DNA binding of nuclear factor-kappaB in human fibroblasts. FEBS letters. 1998;436:329–334. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun J, Kong J, Duan Y, Szeto FL, Liao A, Madara JL, Li YC. Increased NF-kappaB activity in fibroblasts lacking the vitamin D receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E315–322. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00590.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riis JL, Johansen C, Gesser B, Moller K, Larsen CG, Kragballe K, Iversen L. 1alpha,25(OH)(2)D(3) regulates NF-kappaB DNA binding activity in cultured normal human keratinocytes through an increase in IkappaBalpha expression. Archives of dermatological research. 2004;296:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s00403-004-0509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deb DK, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Szeto FL, Wong KE, Kong J, Li YC. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses high glucose-induced angiotensinogen expression in kidney cells by blocking the NF-{kappa}B pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1212–1218. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00002.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aldallal N, McNaughton EE, Manzel LJ, Richards AM, Zabner J, Ferkol TW, Look DC. Inflammatory Response in Airway Epithelial Cells Isolated from Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1248–1256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-627OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manzel LJ, Chin CL, Behlke MA, Look DC. Regulation of bacteria-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2009;40:200–210. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0104OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chin CL, Manzel LJ, Lehman EE, Humlicek AL, Shi L, Starner TD, Denning GM, Murphy TF, Sethi S, Look DC. Haemophilus influenzae from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation induce more inflammation than colonizers. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;172:85–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1687OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu P, Jamaluddin M, Li K, Garofalo RP, Casola A, Brasier AR. Retinoic acid-inducible gene I mediates early antiviral response and Toll-like receptor 3 expression in respiratory syncytial virus-infected airway epithelial cells. Journal of virology. 2007;81:1401–1411. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01740-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haynes LM, Moore DD, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW, Anderson LJ, Tripp RA. Involvement of toll-like receptor 4 in innate immunity to respiratory syncytial virus. Journal of virology. 2001;75:10730–10737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10730-10737.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, Haynes LM, Jones LP, Tripp RA, Walsh EE, Freeman MW, Golenbock DT, Anderson LJ, Finberg RW. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nature immunology. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Akira S, Fujita T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nature immunology. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seth RB, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Antiviral innate immunity pathways. Cell research. 2006;16:141–147. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Luxon BA, Casola A, Garofalo RP, Jamaluddin M, Brasier AR. Expression of respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine gene networks in lower airway epithelial cells revealed by cDNA microarrays. Journal of virology. 2001;75:9044–9058. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9044-9058.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenardo MJ, Fan CM, Maniatis T, Baltimore D. The involvement of NF-kappa B in beta-interferon gene regulation reveals its role as widely inducible mediator of signal transduction. Cell. 1989;57:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ronni T, Sareneva T, Pirhonen J, Julkunen I. Activation of IFN-alpha, IFN-gamma, MxA, and IFN regulatory factor 1 genes in influenza A virus-infected human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:2764–2774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller AL, Bowlin TL, Lukacs NW. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2004;189:1419–1430. doi: 10.1086/382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudd BD, Burstein E, Duckett CS, Li X, Lukacs NW. Differential role for TLR3 in respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine expression. Journal of virology. 2005;79:3350–3357. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3350-3357.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spurrell JC, Wiehler S, Zaheer RS, Sanders SP, Proud D. Human airway epithelial cells produce IP-10 (CXCL10) in vitro and in vivo upon rhinovirus infection. American journal of physiology. 2005;289:L85–95. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00397.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nature reviews. 2008;8:559–568. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ronni T, Matikainen S, Lehtonen A, Palvimo J, Dellis J, Van Eylen F, Goetschy JF, Horisberger M, Content J, Julkunen I. The proximal interferon-stimulated response elements are essential for interferon responsiveness: a promoter analysis of the antiviral MxA gene. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:773–781. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holzinger D, Jorns C, Stertz S, Boisson-Dupuis S, Thimme R, Weidmann M, Casanova JL, Haller O, Kochs G. Induction of MxA gene expression by influenza A virus requires type I or type III interferon signaling. Journal of virology. 2007;81:7776–7785. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00546-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ritchie KJ, Zhang DE. ISG15: the immunological kin of ubiquitin. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2004;15:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, Coyle AJ, Liao SM, Maniatis T. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nature immunology. 2003;4:491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fan C, Yang J, Engelhardt JF. Temporal pattern of NFkappaB activation influences apoptotic cell fate in a stimuli-dependent fashion. Journal of cell science. 2002;115:4843–4853. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker AR, McDonnell DP, Hughes M, Crisp TM, Mangelsdorf DJ, Haussler MR, Pike JW, Shine J, O’Malley BW. Cloning and expression of full-length cDNA encoding human vitamin D receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:3294–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacDonald PN, Dowd DR, Nakajima S, Galligan MA, Reeder MC, Haussler CA, Ozato K, Haussler MR. Retinoid X receptors stimulate and 9-cis retinoic acid inhibits 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-activated expression of the rat osteocalcin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5907–5917. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sutton AL, MacDonald PN. Vitamin D: more than a “bone-a-fide” hormone. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md) 2003;17:777–791. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Groskreutz DJ, Monick MM, Powers LS, Yarovinsky TO, Look DC, Hunninghake GW. Respiratory syncytial virus induces TLR3 protein and protein kinase R, leading to increased double-stranded RNA responsiveness in airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:1733–1740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signaling. Nature reviews. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng DS, Han W, Chen SM, Sherrill TP, Chont M, Park GY, Sheller JR, Polosukhin VV, Christman JW, Yull FE, Blackwell TS. Airway epithelium controls lung inflammation and injury through the NF-kappa B pathway. J Immunol. 2007;178:6504–6513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hippenstiel S, Opitz B, Schmeck B, Suttorp N. Lung epithelium as a sentinel and effector system in pneumonia--molecular mechanisms of pathogen recognition and signal transduction. Respiratory research. 2006;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bals R, Hiemstra PS. Innate immunity in the lung: how epithelial cells fight against respiratory pathogens. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:327–333. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00098803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bikle D. Nonclassic actions of vitamin d. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2009;94:26–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Faseb J. 2005;19:1067–1077. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3284com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, Tavera-Mendoza L, Lin R, Hanrahan JW, Mader S, White JH. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen-Lahav M, Shany S, Tobvin D, Chaimovitz C, Douvdevani A. Vitamin D decreases NFkappaB activity by increasing IkappaBalpha levels. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:889–897. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Szeto FL, Sun J, Kong J, Duan Y, Liao A, Madara JL, Li YC. Involvement of the vitamin D receptor in the regulation of NF-kappaB activity in fibroblasts. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2007;103:563–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tan X, Wen X, Liu Y. Paricalcitol inhibits renal inflammation by promoting vitamin D receptor-mediated sequestration of NF-kappaB signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1741–1752. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007060666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martin LD, Rochelle LG, Fischer BM, Krunkosky TM, Adler KB. Airway epithelium as an effector of inflammation: molecular regulation of secondary mediators. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2139–2146. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10092139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Casola A, Garofalo RP, Haeberle H, Elliott TF, Lin R, Jamaluddin M, Brasier AR. Multiple cis regulatory elements control RANTES promoter activity in alveolar epithelial cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Journal of virology. 2001;75:6428–6439. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6428-6439.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garofalo R, Sabry M, Jamaluddin M, Yu RK, Casola A, Ogra PL, Brasier AR. Transcriptional activation of the interleukin-8 gene by respiratory syncytial virus infection in alveolar epithelial cells: nuclear translocation of the RelA transcription factor as a mechanism producing airway mucosal inflammation. Journal of virology. 1996;70:8773–8781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8773-8781.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mastronarde JG, He B, Monick MM, Mukaida N, Matsushima K, Hunninghake GW. Induction of interleukin (IL)-8 gene expression by respiratory syncytial virus involves activation of nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B and NF-IL-6. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1996;174:262–267. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas LH, Friedland JS, Sharland M, Becker S. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced RANTES production from human bronchial epithelial cells is dependent on nuclear factor-kappa B nuclear binding and is inhibited by adenovirus-mediated expression of inhibitor of kappa B alpha. J Immunol. 1998;161:1007–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haeberle HA, Nesti F, Dieterich HJ, Gatalica Z, Garofalo RP. Perflubron reduces lung inflammation in respiratory syncytial virus infection by inhibiting chemokine expression and nuclear factor-kappa B activation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;165:1433–1438. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hornsleth A, Loland L, Larsen LB. Cytokines and chemokines in respiratory secretion and severity of disease in infants with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. J Clin Virol. 2001;21:163–170. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bont L, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A, van Aalderen WM, Brus F, Draaisma JT, Geelen SM, van Vught HJ, Kimpen JL. Peripheral blood cytokine responses and disease severity in respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:144–149. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a24.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garofalo RP, Patti J, Hintz KA, Hill V, Ogra PL, Welliver RC. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha (not T helper type 2 cytokines) is associated with severe forms of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2001;184:393–399. doi: 10.1086/322788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tekkanat KK, Maassab H, Miller A, Berlin AA, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW. RANTES (CCL5) production during primary respiratory syncytial virus infection exacerbates airway disease. European journal of immunology. 2002;32:3276–3284. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3276::AID-IMMU3276>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Woensel J, Kimpen J. Therapy for respiratory tract infections caused by respiratory syncytial virus. European journal of pediatrics. 2000;159:391–398. doi: 10.1007/s004310051295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kota S, Sabbah A, Chang TH, Harnack R, Xiang Y, Meng X, Bose S. Role of human beta-defensin-2 during tumor necrosis factor-alpha/NF-kappaB-mediated innate antiviral response against human respiratory syncytial virus. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:22417–22429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710415200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]