Abstract

Mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS IH; Hurler syndrome) is a congenital deficiency of α-L-iduronidase, leading to lysosomal storage of glycosaminoglycans that is ultimately fatal following an insidious onset after birth. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a life-saving measure in MPS IH. However, because a suitable hematopoietic donor is not found for everyone, because HCT is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and because there is no known benefit of immune reaction between the host and the donor cells in MPS IH, gene-corrected autologous stem cells may be the ideal graft for HCT. Thus, we generated induced pluripotent stem cells from 2 patients with MPS IH (MPS-iPS cells). We found that α-L-iduronidase was not required for stem cell renewal, and that MPS-iPS cells showed lysosomal storage characteristic of MPS IH and could be differentiated to both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells. The specific epigenetic profile associated with de-differentiation of MPS IH fibroblasts into MPS-iPS cells was maintained when MPS-iPS cells are gene-corrected with virally delivered α-L-iduronidase. These data underscore the potential of MPS-iPS cells to generate autologous hematopoietic grafts devoid of immunologic complications of allogeneic transplantation, as well as generating nonhematopoietic cells with the potential to treat anatomical sites not fully corrected with HCT.

Introduction

The seminal insight that cells with 2 different enzyme deficiencies can functionally complement each other1 made possible the use of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) to correct the biochemical and clinical phenotype of several fatal nonmalignant enzymatic deficiency disorders, including Hurler syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type I-Hurler, MPS IH).2 In MPS IH the deficiency of α-L-iduronidase (IDUA) results in the toxic accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAG) heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate. This in turn leads to progressive cellular and multiorgan dysfunction in viscera, bone, connective tissue, and brain. Untreated, early death is observed usually between 5 and 10 years of age.3

The sole agent needed for MPS IH correction is the missing IDUA, which after secretion and intercellular transfer is taken up by IDUA-deficient cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Weekly doses of intravenous IDUA have been used for mild forms of MPS I. However, because IDUA does not cross the blood-brain barrier efficiently, enzyme replacement therapy alone is not indicated for the severe form of IDUA deficiency, MPS IH.4 Allogeneic HCT, in contrast, leads not only to donor hematopoietic engraftment and systemic expression of IDUA but also to donor myeloid cells crossing the blood-brain barrier and correcting IDUA deficiency in the brain.5–8 Although HCT is a life-saving measure in MPS IH, a suitable HCT donor is not found for everyone. To achieve a cure, children with MPS IH must survive both the disease and its therapy because allogeneic HCT is associated with significant morbidity and mortality from physical and immune injury by both the myeloablative conditioning regimen and the transplantation of an immunologically matched allogeneic cellular graft.9–11 In contrast to some malignancies,12 in patients with congenital enzymopathies there is no known benefit of immune reaction between the host and the donor cells.

Patient-specific stem cells, such as recently identified induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells,13–15 present an opportunity to use the hematopoietic progeny of gene-corrected autologous cells clinically in a way that may preclude the immunologic complications of allogeneic HCT. Induction of iPS cells from patients with MPS IH may also provide a means of better understanding the sequence of downstream events initiated by IDUA deficiency in the most immature human cell type available. With such data, we would be able to model the cellular interactions among various cell types derived from the same IDUA-deficient iPS culture and thereby also develop new treatment approaches that could be used alone or with HCT.

Here, we show that iPS cells can be obtained from patients with MPS IH (MPS-iPS cells) and that their therapeutic transgenesis is possible. We report that the MPS-iPS cells can be derived from both keratinocytes and bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs). MPS-iPS cells can be differentiated to both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells. The specific epigenetic profile associated with de-differentiation of MPS IH fibroblasts into MPS-iPS cells is maintained when MPS-iPS cells are gene-corrected with virally delivered IDUA. These data underscore the potential of MPS-iPS cells in modeling MPS IH in the development and future use of gene-corrected MPS-iPS cells to generate autologous hematopoietic grafts as well as generating nonhematopoietic cells with the potential to treat anatomical sites not fully corrected with HCT.

Methods

Patients

After obtaining consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Minnesota, skin or marrow cells were collected from healthy volunteers and from patients with MPS IH. Detailed methods describing isolation of keratinocytes and MSCs are included as supplemental Materials (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

iPS cells

Four reprogramming factors, OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC were used to produce retroviral supernatants. Each of the viral supernatants was produced by transfecting 293T/17 cells with the use of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with 3 plasmids: one cargo plasmid (containing the reprogramming gene), a plasmid expressing the VSV-G envelope gene, and a helper plasmid with the retroviral Gag/Pol gene. The plasmids were obtained from Addgene (www.addgene.org). Forty-eight to 72 hours after transfection, viral supernatants were harvested, centrifuged at 400g for 15 minutes, and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter. Viral supernatant containing the IDUA gene was produced by transfecting 293T/17 cells with 3 plasmids: one cargo plasmid containing the IDUA gene, the pMDG plasmid expressing the envelop gene and a helper plasmid with the Gag/Pol gene. The supernatant was collected as described earlier and concentrated 100-fold with the use of high-speed centrifugation.

Approximately 50 000 keratinocytes or 100 000 MSCs per well of a 6-well plate were plated and infected with a 1:1:1:1 mix of retroviral supernatants of pMIG containing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC in the presence of 5μg/mL protamine sulfate. Transduction consisted of a 45-minute exposure to the virus at 1800 rpm at room temperature; supernatants were left in contact with the cells for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. The next day, cells were exposed to the virus at 1800 rpm for a second time. Cells were placed in plates coated with the use of a Coating Matrix Kit (Cascade Biologics) and maintained in keratinocyte medium (EpiLife Medium, Cascade Biologics; 0.06mM calcium chloride, plus Human Keratinocyte Growth Supplement) at 37°C, 5% CO2. Five days later, cells were trypsinized and seeded onto feeder layers of irradiated CF1 murine embryonal fibroblasts (MEFs). After 24 hours, medium was changed to human embryonic stem (ES) cell medium, consisting of Dulbecco minimal essential medium (DMEM)/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% KnockOut Serum Replacement (Invitrogen), 2mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen), 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), 1X nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 mg/mL streptomycin, and 10 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (R&D Systems). Cultures were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, with daily medium changes. Starting 1 week after plating onto MEFs, medium was supplemented with 1μM PD0325901 and 1μM CT 99 021 (both from Stemgent) for 1 week. Colonies were picked based on structure 30-60 days after the initial infection.

We identified iPS cell colonies with the use of live staining with TRA-1-60 antibody (1:400; Millipore) and secondary antibody Alexa 488–conjugated anti–mouse immunoglobulin M (1:400; Invitrogen) diluted in human ES medium and added into the culture plate. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour before medium was changed to fresh conditioned medium. TRA-1-60+ colonies were identified under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI6000B). To confirm that the iPS cells were not contaminated with donor cells, competitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of variable tandem repeat regions was performed as described.16

To confirm their cellular phenotype, the iPS cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes. If nuclear permeation was needed, cells were treated with 0.2% Triton-X (Sigma) in PBS for 30 minutes, blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 2 hours, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Antibodies targeting the following antigens were used: TRA1-60 (MAB4360, 1:400), TRA1-81 (MAB4381, 1:400), SSEA4 (MAB4304, 1:200), and SSEA3 (MAB-4303, 1:200), all from Chemicon; OCT3/4 (AB27985, 1:200), SOX2 (AB5603, 1:500), both from Abcam; and NANOG (EB068601:100) from Everest. Cells were incubated with secondary Alexa Fluor Series antibodies (all 1:500; Invitrogen) for 2 hours at room temperature and then with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1 μg/mL; Invitrogen) for 10 minutes. Images were examined with a Leica DMI6000B microscope equipped with Q-Imaging Retiga 2000R Camera and Q-Capture software. Direct alkaline phosphatase activity was analyzed per the manufacturer's recommendations (Millipore).

Reverse transcription PCR

RNA was isolated with a GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma) and treated with TURBO DNA-free (Ambion) to remove genomic DNA. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with a Superscript III First Strand Synthesis SuperMix for quantitative reverse transcription PCR (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed with TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (list follows) and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, No AmpErase UNG (Applied Biosystems) per the manufacturer's protocol.

TaqMan Gene Expression Assays were as follows: GAPDH Hs 99999905_m1; POU5F1 00999634_gH; SOX2 00602736_s1; NANOG 02387400_g1; KLF4 00358836_m1; MYC 00153408_m1; LIN28 00702808_s1; REX01 00810654_m1; ABCG2 01053790_m1; DNMT3 01003405_m1; IDUA 00164940_m1, brachyury 00610080_m1, TAL-1 01097987_m1, GATA-2 00231119_m1, CD34 00156373_m1, CD38 00277045_m1 with GAPDH 99999905_m1 used as an endogenous control.

Exogenous and total levels of OCT4 and SOX2 were determined as described17 with the use of the following primers: OCT4 Endo Forward, CCTCACTTCACTGCACTGTA; OCT4 Endo Reverse, CAGGTTTTCTTTCCCTAGCT; OCT4 Total Forward, AGCGAACCAGTATCGAGAAC; OCT4 Total Reverse, TTACAGAACCACACTCGGAC; SOX2 Endo Forward, CCCAGCAGACTTCACATGT; SOX2 Endo Reverse, CCTCCCATTTCCCTCGTTTT; SOX2 Total Forward, AGCTACAGCATGATGCAGGA; and SOX2 Total Reverse, GGTCATGGAGTTGTACTGCA.

Expression levels were measured in duplicate. For genes with expression below the CT fluorescence threshold, the CT was set to 40 to calculate the relative expression. Analysis and subsequent calculations were done with the use of an ABI PRISM 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems).

Bisulfite genomic sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated with a PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). Bisulfite treatment was done with an EpiTect Bisulfite kit (QIAGEN). Converted DNA was PCR-amplified with OCT4-specific primer sets and NANOG-specific primer sets.18 PCR products were gel purified with a PureLink Quick Gel Extraction and PCR Purification Combo Kit (Invitrogen) and cloned into bacteria with the use of the TOPO TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing (Invitrogen).

In vitro differentiation

For hematopoietic differentiation, embryoid bodies produced by confluent cultures were harvested by enzymatic dissociation with Accutase (Millipore) to single cells, which were seeded to AggreWell plates (StemCell Technologies) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were differentiated for 1 day in basic embryoid body (EB) medium, containing KnockOut DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.1mM nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 0.1mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 1mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 50μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and 200μg/mL Human holo-Transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich). After 24 hours, EBs were transferred to low-attachment dishes, and human stem cell factor (300 ng/mL), human Flt3-ligand (300 ng/mL), human interleukin-3 (10 ng/mL), human interleukin-6 (10 ng/mL), granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (50 ng/mL), and human bone morphogenetic protein 4 (50 ng/mL) were added to the cultures (all from R&D Systems). EBs were collected at different time points and dissociated into single cells for further characterization by flow cytometric analysis, RT-PCR, and colony-forming unit (CFU) assays. For the CFU assays, cells were placed in human methylcellulose-enriched media (R&D Systems), and colonies were enumerated 14 days later. Cytospins were stained with Wright's stain to identify differentiated cells within the CFU colonies.

In vivo differentiation

For teratoma formation, NOG young adult mice were injected with 1 million cells resuspended in mixture of DMEM/F12, Matrigel, and collagen (ratio, 2:1:1; 40 μL per mouse) into the right quadriceps muscle with the use of a 29-gauge needle attached to a 0.3-mL insulin syringe. Tumors were harvested in 4-8 weeks, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin.

Correction of the human iPS cells

The human IDUA cDNA was amplified with PfuUltraHigh-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Stratagene) supplemented with 1X Q Solution (QIAGEN) under the following conditions with the use of primers that incorporated a 5′ AgeI and 3′ SalI restriction endonuclease site: 95°C for 5 minutes, 34 cycles of 95°C for 45 seconds, 56.5°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 2 minutes. The PCR product was gel-purified (QIAGEN), digested with AgeI and SalI (New England BioLabs), and ligated into the pSin-EF2-Sox2 Puro plasmid obtained from Dr Robert Hawley, George Washington University via Addgene with the use of T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen). The IDUA lentiviral supernatant was added to the human iPS cultures in the presence of 8μg/mL protamine sulfate and placed at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight. These cells were expanded, and individual colonies were tested for enzymatic activity. A colony that was positive for IDUA activity was expanded, and this line was used for subsequent experiments. Linear-amplification-mediated PCR was performed to identify IDUA transgene integration sites in the genome of the iPS cells as described.19

Quantification of GAGs and IDUA activity

Human iPS cells were removed from the MEF (mouse embryonal fibroblast) cells by incubating at 37°C in a buffer containing 10mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and HBSS (Hanks balanced salt solution), pelleted down by centrifugation at 1000g for 5 minutes, and lysed with extraction buffer (20mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane] pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 5mM EDTA) by a 15-minute incubation at 37°C. Proteinase-K and Rnase-A (Invitrogen) were added to lysates at final concentrations of 250μg/mL and incubated at room temperature for 2 minutes, followed by a 20-minute incubation at 55°C. Soluble GAG was measured by combining lysate with an association reagent containing 32 mg/L, 1,9-Dimethylmethylene blue chloride (DMMB; Polysciences), 0.2M GuHCl, 5% ethanol, 0.2% formic acid, and 2 g/L sodium formate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc). GAG-DMMB complex was pelleted by centrifugation at 15 000g for 15 minutes, supernatant was discarded, and GAG-DMMB pellets were solubilized in 1.0 mL of 50mM sodium acetate pH 6.8, 10% 1-propanol, and 4M GuHCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc). Absorbence was read at 656 nm (DMMB) and 540 nm (background) with the use of a Synergy 2 plate reader (BioTek) and normalized to genomic DNA absorbance (measured at 260 nm).

For IDUA activity measurements, cells were pelleted and lysed in Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega), and IDUA enzymatic activity was assessed with 4-methylumbelliferyl α-L-iduronide as the substrate (NBS Biological Ltd).

Data analysis

Differences between measurements were evaluated with the Student t test, with P values < .05 considered significant.

Results

MPS-iPS cells can be generated from both keratinocytes and MSCs

To increase the likelihood of successful induction of iPS cells from a limited amount of human tissue, we isolated skin keratinocytes (KCs) and bone marrow MSCs from 2 boys with MPS IH who had received an allogeneic HC transplant (Table 1). KCs, obtained from a 3-mm skin plug, were chosen because they have been used extensively for this purpose20 and are often preferred because human KCs reprogram faster than human fibroblasts.21 The cultured primary KCs had a characteristic cobblestone appearance and expressed KC-specific cytokeratin 5 (supplemental Figure 1A-B). MSCs were obtained from bone chips removed during an orthopedic procedure for dysostosis multiplex, which required surgical correction. MSCs were chosen because they may be more permissive to reprogramming than fully differentiated somatic cells because of their capacity to widely differentiate into distinct cell types within mesodermal lineage.22–24 To further define their phenotype, expression of surface markers was assessed by flow cytometry: MSCs were positive (> 95%) for CD13, CD29, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD166; and negative (< 1%) for CD11b, CD19, CD30, CD31, CD34, CD43, CD45, and OCT3/4 (data not shown). To formally show oligopotency of the MSCs derived from our patient with MPS IH, we have induced the MPS-MSCs to acquire in vitro cell phenotypes of osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes (supplemental Figure 1). Because donor bone marrow and umbilical cord blood cells can engraft in nonhematopoietic tissues after HCT,25,26 we wanted to determine whether donor wild-type cells were present in our KC and MSC cultures. Consistent with the notion that such donor chimerism occurs mainly in the setting of tissue injury or graft-versus-host disease,25,26 that was not present in our patients, we were unable to detect any IDUA enzymatic activity by 4-methylumbelliferyl α-L-iduronide chromatographic assay in any MPS-KCs and MPS-MSCs (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patient and iPS cell characteristics

| Patient | IDUA mutations | Sex | Age at HCT, y | Time after HCT, y | Donor cells | No. of iPS colonies per 100 000 cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Y167X | Male | 1.1 | 0.2 | KC | 2 |

| W402X | ||||||

| P2 | W402X | Male | 1.8 | 0.8 | KC | 14 |

| W402X | MSC | 4 |

iPS indicates induced pluripotent stem; IDUA, iduronidase gene; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; P, patient; Y, tyrosine; X, unknown amino acid; KC, keratinocytes; W, tryptophan; and MSC, mesenchymal stromal cells.

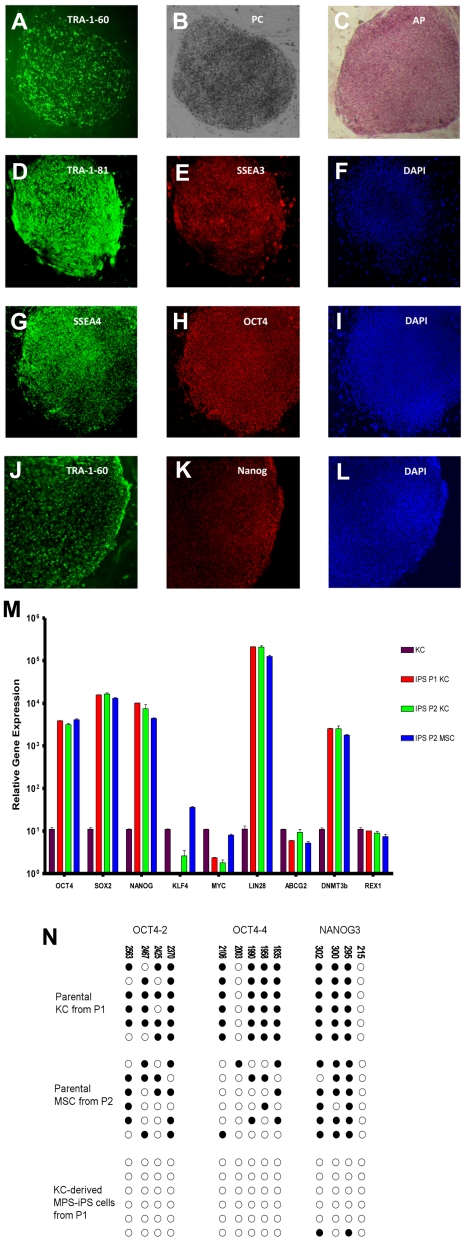

To derive MPS-iPS cells, MPS-KCs (from patient 1 [P1] and patient 2 [P2]) and MPS-MSCs (from P2; Table 1) were transduced with retroviral vectors carrying 4 known reprogramming transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC) that are typically associated with pluripotency. Transduced cells were cultured on supportive stroma of irradiated MEFs. Within 2-3 weeks, flat colonies of MPS-iPS cells with clear-cut round edges emerged from the 2-dimensional MEF culture (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Figures 2-3) with roughly similar efficiency in KC and MSC cultures (Table 1). Compared with parental MPS-KCs and MPS-MSCs, the MPS-iPS cells showed persistent mRNA expression of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28, ABCG2, DNMT3b, and REX1 and transient mRNA expression of c-MYC and KLF4, which is expected to occur in the wild-type iPS cells (Figure 1M; supplemental Figure 4). MPS-iPS cells expressed protein markers characteristic of reprogrammed immature cells: OCT4, NANOG, stage-specific embryonic antigen-3 (SSEA-3) and SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 and TRA-1-81, and alkaline phosphatase (Figure 1C-L). Because these reprogramming factors are thought to activate a network of transcriptional factors, which in turn induce epigenetic changes,18,20,21,27,28 we used bisulfite sequencing to confirm that the methylation status of OCT4 and NANOG promoters in MPS-iPS cells showed a pattern characteristic of iPS cells in which OCT-4 and NANOG promoter sequences are unmethylated in contrast to KCs and MSCs15,29 (Figure 1N). Both MPS-KC– and MPS-MSC–derived MPS-iPS cells from the 2 patients had normal male karyotype as determined by high-resolution chromosomal G-banding (supplemental Figure 5). In further support of a lack of contamination from donor cells after HCT, MPS-iPS cells derived from either MPS-KCs or MPS-MSCs were fully host-derived when assessed by competitive PCR of variable number tandem repeats (data not shown). Collectively, the transcription profile and cellular phenotype of MPS-iPS cells from both patients were consistent with structural and phenotypical gain of pluripotency. Total GAG content, a hallmark of the biochemical defect in MPS IH, in unsorted cultures of MPS-iPS was significantly elevated compared with wild-type iPS cells (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Induction of MPS IH somatic cells into MPS-iPS cells. (A) Live culture stained with TRA-1-60 antibody 4 weeks after transduction. (B) Phase contrast (PC) image of the same human ES cell-like colony. To confirm their ability to express ES cell proteins, human KCs derived from P1 were stained with alkaline phosphatase (C) and immunostained with TRA-1-81 (D), SSEA-3 (E), SSEA-4 (G), OCT4 (H), TRA-1-60 (J), and Nanog (K). Corresponding images stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) show nuclei of individual cells in the colonies (F,I,L). Images in panels A-C were obtained with a Leica DMIL scope, magnification 10×/0.22. Images were acquired with an Optronics camera and Optronics MagnaFire software. Fluorescein isothiocyanate color block was used. Images in panels D-L were obtained with an Olympus BX61 FV500 Confocal Microscope, magnification 10×/.40. Argon, green HeNe, and blue diode lasers were used to acquire the images in Olympus FluoView software Version 4.3. All images were taken at room temperature. (M) Quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, c-MYC, LIN28, ABCG2, DNMT3b, and REX1 expression levels in KC-derived iPS cells from P1 (red bars), KC-derived iPS cells from P2 (green bars), and MSC-derived iPS cells from P2 (blue bars), respectively. All values were normalized against endogenous GAPDH expression. Because MPS-KCs and MPS-MSCs expressed statistically indistinguishable levels of these ES cell marker genes, their values were plotted against expression levels of parental MPS-KCs from P1 (black bars). (N) Bisulfite sequencing of the OCT4 and NANOG promoters in parental MPS-KCs (from P1), parental MPS-MSCs (from P2), and MPS-iPS cells derived from KCs in P1. Open circles denote unmethylated CpGs, and filled circles represent methylated CpGs. CpG position relative to the downstream transcriptional start site is shown above each column. Sequencing reactions of specific amplicons are represented by each row of circles. KC indicates keratinocytes; MSC, mesenchymal stromal cells; iPS cells, induced pluripotent cells; P, patient; MPS IH, mucopolysaccharidosis type I, Hurler syndrome.

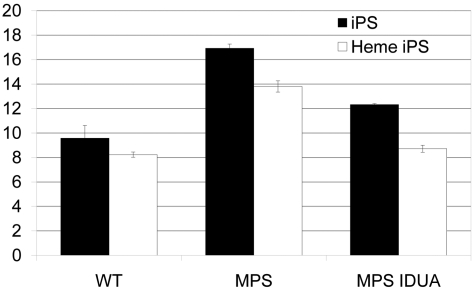

Figure 2.

Accumulation of GAG in MPS IH iPS cells. GAGs, normalized to genomic DNA, were significantly higher in both MPS IH cell types: MPS IH iPS cells vs wild-type iPS cells (mean ± SEM, 16.9 ± 0.4 vs 9.6 ± 1.0; P < .02); and MPS IH heme iPS vs wild-type heme iPS (13.8 ± 0.5 vs 8.2 ± 0.2; P < 0.01). GAG levels in gene-correlated cells were significantly lower in both cell types: MPS IH iPS cells vs MPS IH IDUA iPS cells (mean ± SEM, 12.3 ±0.1; P < .01); and MPS IH heme iPS cells vs MPS IH IDUA heme iPS cells (8.7 ± 0.3; P < .01). When GAG levels of gene-corrected cells were compared to that of wild-type cells, no significant difference was found. These data are the results of 3 independent measurements for each cell type and genotype. GAG indicates glycosaminoglycan; iPS, induced pluripotent stem cells; Heme iPS, iPS cell-derived hematopoietic cells; WT, wild type; and MPS, mucopolysaccharidosis type I, Hurler syndrome.

Gene correction on MPS-iPS cells

To achieve the high levels of IDUA expression sufficient for phenotypic rescue in patients with MPS IH after allogeneic HCT,30 P1 MPS-iPS cells were transduced with lentivirus harboring wild-type human IDUA gene and green fluorescent protein for tracking purposes. Three corrected iPS cell clones were generated: one from P1 (IDUA-corrected keratinocyte-derived iPS cells) and 2 from P2 (IDUA-corrected keratinocyte-derived iPS cells and IDUA-corrected MSC-derived iPS cells). Two weeks after transduction, ∼ 75% of MPS-iPS cells expressed green fluorescent protein (data not shown). Linear-amplification-mediated–PCR analysis showed lentiviral-mediated integration of the IDUA transgene in iPS cells (hematopoietically differentiated, as described in “MPS-iPS cells differentiate into both nonhematopoietic and hematopoietic cells”) from both patients with MPS IH.19 Of note, none of the integrants appear to interfere with the function of known tumor suppressor genes, oncogenes, or genes operational in cell cycle and proliferation (supplemental Table 1). IDUA mRNA expression in unsorted cultures of IDUA-transduced MPS iPS cells was significantly higher than in wild-type IDUA iPS cells: nontransduced MPS iPS versus wild-type iPS cells (0.5 ± 0.05 vs 1.9 ± 0.05; P < .05) and MPS iPS versus gene-corrected MPS iPS cells (0.5 ± 0.05 vs 8.5 ± 0.8; P < .05). Corresponding IDUA activity also was higher in gene-corrected versus noncorrected MPS iPS cells: (18.4 ± 0.29 vs 2.7 ± 0.09 nmol/mg/h, respectively; P < .05) and was ∼ 2 times higher than wild-type IDUA levels (wild-type iPS vs gene-corrected MPS-iPS cells; 9.5 ± 0.16 vs 18.4 ± 0.29 nmol/mg/h; P < .05).

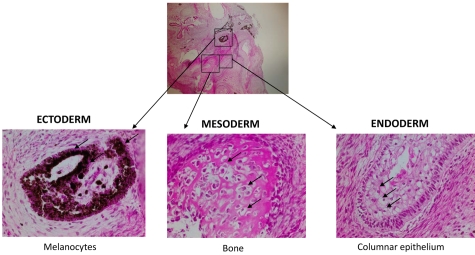

MPS-iPS cells differentiate into both nonhematopoietic and hematopoietic cells

To provide further evidence of the identity of iPS cells on a functional level, MPS-iPS cells were injected intramuscularly into immune-deficient mice. Within 6-8 weeks well-differentiated cystic teratomas were observed, confirming the phenotype-defining ability of iPS cells to differentiate in vivo into cells of ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal origins (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Nonhematopoietic differentiation of MPS-iPS cells. Same histologic section of mature teratoma from immunodeficient mouse injected with MPS-iPS cells (top, magnification 4×) shows melanocytes of ectodermal origin (bottom left arrows), osteoid deposition and osteocytes of medodermal origin (bottom middle arrows), columnar epithelium of endodermal origin (bottom right; goblet cells are indicated by arrows; magnification 20×). Similar mature teratomas with contribution of ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal-derived cells formed after injection of early (< 20) passage and late (> 20) passage iPS cells from wild-type keratinocytes and MSCs (n = 11), from patient 1 (keratinocyte-derived iPS cells, n = 3; IDUA-corrected keratinocyte-derived iPS cells, n = 3) and from patient 2 (keratinocyte-derived iPS cells, n = 2; MSC-derived iPS cells, n = 2; data not shown). Hematoxylin-eosin stain. Images were obtained with an Olympus BX51 Microscope, magnification 4×/0.16 and 20×/0.70. Spot RT camera and Spot RT software v3.2 were used in acquiring the images. All images were taken at room temperature.

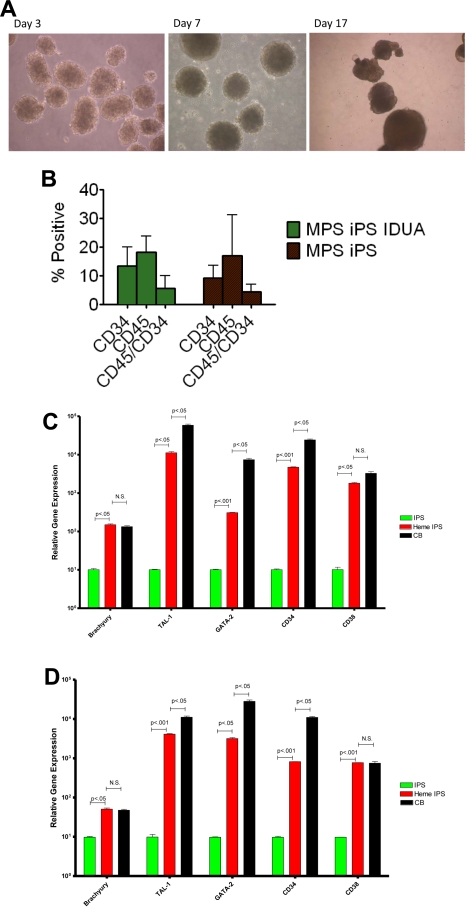

One of the mesodermal lineages, hematopoietic, is directly relevant to our ultimate goal of generating gene-corrected cells for autologous HCT. To test the hematopoietic potential of the MPS-iPS cells, EBs were generated (Figure 4A) and were enzymatically dissociated into single cells. After seeding in low-attachment dishes, cells were induced to differentiate in medium containing human hematopoietic growth factors: stem cell factor, Flt3-ligand, interleukin-3, interleukin-6, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, and bone morphogenetic protein 4. At different time points differentiated cells were examined for expression of pan-hematopoietic marker CD45 for and an antigen found on progenitor hematopoietic cells, CD34. There was no significant difference in CD34 and CD45 expression by hematopoietic progeny of wild-type iPS cells, MPS IH iPS cells, and IDUA-corrected iPS cells (Figure 4B). GAG levels in the hematopoietic cells derived from IDUA-corrected iPS cells showed a decreasing trend, albeit not significant, compared with the hematopoietic cells derived from MPS IH iPS cells (uncorrected vs IDUA-corrected, mean ± SEM, 23.5 ± 0.7 vs 16.9 ± 4.6, P = .2). To further delineate this mesodermal-to-hematopoietic transition, we assessed the expression profile of these cells and compared them with undifferentiated iPS cells. Differentiated MPS-iPS cells (and wild-type iPS cells) expressed mesodermal markers (eg, brachyury), transcription factors consistent with commitment to the hematopoietic lineage (eg, GATA-1 binding partner stem cell leukemia/TAL-1 and GATA-2), and surface antigens associated with both hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs; eg, CD34) and differentiated HSCs (eg, CD38; Figure 4C-D). Compared with CD34+ cord blood cells, expression levels of 2 of the genes assessed (brachyury and CD38) were not statistically different in hematopoietic progeny from either wild-type or gene-corrected MPS iPS cells. These data also suggest that the hematopoietic progeny cells of iPS cells are not homogenous, but rather the expression patterns reflect both mesodermal and hematopoietic cells at different stages of lineage commitment.

Figure 4.

Hematopoietic differentiation of MPS-iPS cells. (A) Embryoid bodies were derived from iPS cells and induced to differentiate into hematopoietic cells. (B) Cells were harvested and assayed for expression of hematopoietic markers CD45 and CD34. No statistically significant differences were found when hematopoietic progeny of the MPS-iPS cells and gene-corrected MPS-iPS (MPS iPS IDUA) cells were compared as determined by CD34 expression (mean ± SEM, 9.2 ± 1.4 vs 13.5 ± 2.5), CD45 expression (17.0 ± 4.5 vs 18.2 ± 2.1), and simultaneous expression of CD34 and CD45 (4.5 ± 0.8 vs 5.7 ± 1.6; all P > .05). These data did not differ significantly from the CD34 and CD45 expression of the hematopoietic progeny of wild-type iPS cells and in iPS cells of any genotype at early (< 20) passage and late (> 20) passage iPS (data not shown). (C) Quantitative PCR analysis of BRACHYURY, TAL-1, GATA-2, CD34, and CD38 expression levels in wild-type iPS cells (IPS, green bars), hematopoietic progeny of wild-type iPS cells (heme IPS, red bars). and CD34+ cord blood cells (CB; black bars). (D) Quantitative PCR analysis of the same gene set in the MPS-iPS cells (IPS, green bars), hematopoietic progeny of gene-corrected MPS- iPS cells (Heme IPS, red bars), and CD34+ CB cells (black bars). Expression of all these genes in iPS cells of both wild-type and mutant genotype (each set arbitrarily to equal 101) was significantly elevated after induction of hematopoietic differentiation mirroring expression of these genes in hematopoietic progenitor cells derived from human CB. All values were normalized against endogenous GAPDH expression. (A) Images were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse TS100 scope, magnification 10×/0.25. Images were taken with a Nikon Coolpix 4300 digital camera with a microscope adaptor from Martin Microscope MMCOOL S/N:1228 Nikon UR-E4. All images were taken at room temperature.

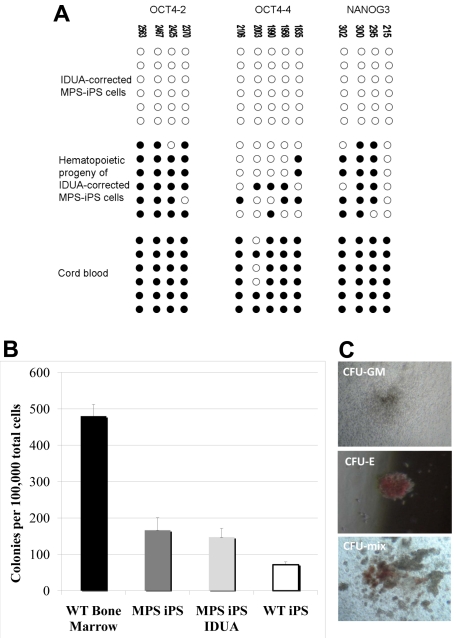

Critically, the methylation pattern of the gene-corrected MPS-iPS cells induced to acquire hematopoietic phenotype has reverted from largely unmethylated chromatin of iPS cells into a more methylated one characteristic of differentiated cells with quiescent OCT4 and NANOG genes (Figure 5A). This is consistent with the expected progressive loss of the pluripotent state with differentiation and maintenance of the physiologic differentiation profile in gene-corrected MPS iPS cells. To further define the commitment of the cells expressing hematopoietic surface antigens to hematopoietic lineage, their capacity to function as CFUs was evaluated. When plated in semisolid medium, both erythroid and myeloid colonies formed (Figure 5B-C). The colony-forming capacity of the hematopoietic progeny of MPS-iPS cells and IDUA-corrected iPS cells was comparable to the colony-forming capacity of the hematopoietic progeny of wild-type iPS cells (Figure 5B). Although not equal to the colony-forming ability of wild-type bone marrow (Figure 5B), these results support the recent observations of others31 who noted early senescence of iPS cell–derived hemangioblastic derivatives. Importantly, our data indicate that IDUA deficiency does not result in a cellular state that is less permissive to hematopoietic differentiation than that of wild-type iPS cells, confirms that transgenesis of MPS-iPS cells with IDUA is feasible, with both MPS-iPS cells and IDUA-corrected iPS cells able to differentiate into cells with hematopoietic potential.

Figure 5.

Methylation patterns and hematopoietic phenotypes of gene-corrected MPS-IPS and their hematopoietic progeny. (A) Bisulfite sequencing of the OCT4 and NANOG promoters in gene-corrected KC-derived MPS-iPS cells from P1, their hematopoietic progeny, and human umbilical cord blood cells. Open circles denote unmethylated CpGs, and filled circles represent methylated CpGs. CpG position relative to the downstream transcriptional start site is shown above each column. Sequencing reactions of specific amplicons are represented by each row of circles. (B) When plated in semisolid methylcellulose medium (100 000 total unsorted cells per experiment), colony-forming units (CFUs) formed. CFUs from iPS-derived hematopoietic cells were compared with wild-type bone marrow cells (6 independent experiments were performed, mean ± SEM, 480 ± 32). Wild-type (WT) bone marrow cells formed significantly more colonies than hematopoietic derivatives of WT iPS cells, MPS-iPS cells, and gene-corrected MPS-iPS cells (all P < .01). There was no significant difference, however, among the number of CFUs from uncorrected MPS-iPS–derived hematopoietic cells (MPS iPS, 12 experiments were performed), corrected MPS-iPS–derived hematopoietic cells (MPS iPS IDUA, 10 experiments), and the WT iPS-derived hematopoietic cells (WT iPS, 6 experiments): 166 ± 34 versus 147 ± 24 versus 71 ± 8; all P > .05. (C) The examples of granulocyte/macrophage CFU (CFU-GM), erythroid CFU (CFU-E), and mixed CFU (CFU-mix) are shown. (C) Images were taken with an Olympus CK2 microscope, magnification 4× EA4 0.10 160/−. Images were taken with a Nikon Coolpix 4300 digital camera with a microscope adaptor from Martin Microscope MMCOOL S/N:1228 Nikon UR-E4. All images were taken at room temperature.

Discussion

To our knowledge these are the first data to report that autologous iPS cells can be obtained from patients with MPS IH. We found that iPS cells can be generated from skin and stromal bone marrow cells of patients with MPS IH. These MPS-iPS cells can be gene-corrected and induced to differentiate into hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells. Our observation that the MPS-iPS cells have significantly higher GAG accumulation compared with wild-type iPS cells is consistent with the current view that the pathogenic cascade resulting from the IDUA gene lesion is established early in prenatal development. Thus, early intervention before the damage becomes irreversible and profound may provide the best outcome in patients with MPS IH. This is highly relevant because neonatal screening for mucopolysaccharidoses, which is rapidly expanding in multiple countries, may increase the demand for early HCT and, along with it, its delivery with minimal treatment-related morbidity and mortality in the affected newborns. In the future, gene-corrected MPS-iPS cells could be used not only to generate an autologous hematopoietic graft but also to generate nonhematopoietic cells with the potential to treat anatomical sites, such as heart valves, not optimally corrected by successful and life-saving HCT. Individually or together, these 2 strategies have the potential to decrease the complications observed with allogeneic HCT and to result in improved survival and quality of life for patients with MPS IH and other lysosomal storage diseases.

In addition, MPS-iPS cells provide a novel model system to study pathogenesis of MPS IH and related disorders,27 and can be obtained from both skin cells and bone marrow stromal cells with comparable efficiency. Compared with studies of differentiated human cells and in animal models of MPS IH, iPS cell studies have the added benefit of offering the opportunity for a more extensive analysis of the cellular effects of IDUA deficiency independent of the secondary effects of GAG on systemic inflammatory responses. Because nearly all cell types can be derived from the iPS cells, iPS cells may have advantages over animal models, which are confounded by the obvious differences in development, lifespan, and species-specific consequences of cellular pathology in numerous tissue types affected by IDUA deficiency.32,33

We also show that the imbalance between production and clearance of unprocessed GAG is evident already in the ES cell-like MPS-iPS cells. Although IDUA deficiency and GAG excess are the initiating factors of MPS IH phenotype,34 subsequent to this impairment changes in numerous structural and signaling molecules are altered. It is the signal amplification through these pathways that underlies the varied and tissue-specific pathology in MPS IH,35 indicating that many of the consequences of IDUA deficiency are not cell autonomous.36,37 Related to this, one of the main physiologic roles of the lysosome, which is engaged in autophagosomal and proteosomal processes as a functional component of the endosomal-lysosomal system, is recycling of degraded macromolecules, such as GAG and proteoglycans. Experimental evidence suggests that a deficiency of IDUA hydrolase activity, accompanied by GAG storage in MPS IH and other lysosomal storage disorders, results in a state of a “sick lysosome.”38 As a result, the MPS IH is not purely a state of overabundance (of GAGs) but also—because of impaired recycling of macromolecules—a state of scarcity.35 Interestingly, in contrast to other congenital disorders, such as those affecting DNA repair genes in Fanconi anemia,29,39 IDUA does not appear to be necessary for stem cell self-renewal and generation of iPS cells.

Recently iPS cells from several mouse models of lysosomal storage disorders have been described,40 but induction of iPS cells from human cells has been reported to date for only one human lysosomal storage disorder, type III Gaucher disease.27 There are ≥ 2 potential critical advantages of HSC derivation from genetically corrected iPS cells instead of gene correction of autologous HSCs. First, transgenesis of iPS cells, especially with nonviral means, is easier than that of HSCs, which are sensitive to ex vivo manipulations. Second, because the iPS cells are more robust, they are more amenable to the longer-term culture needed for full molecular definition of gene-corrected iPS cells and elimination of cells with potentially unsafe genotoxic events. In a conceptually different line of experimentation, murine erythroleukemia cells, and HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells from genetically engineered IDUA-deficient mice have been transduced with lentivirus harboring an expression cassette, in which the expression of IDUA gene is regulated by erythroid-specific promoter. This phenotypic change of erythroid cells,41 distinct from the induction of pluripotency in the form of human MPS-iPS cells reported in our study, provides further evidence that cell fates of differentiated cells are malleable, that transplanted cells need not be stem cells per se to be useful, and that high IDUA expression from various donor cells, including erythroid cells and HSCs and their progeny, can functionally complement IDUA deficiency in the recipient.

The potential benefits of gene-corrected progeny of iPS cells need not be limited to the hematopoietic lineage. Some of the tissue-specific manifestations of MPS IH in cardiovascular, nervous, and skeletal systems persist even after full hematopoietic donor engraftment after allogeneic HCT, presumably because of the restricted distribution of IDUA from the donor hematopoietic graft. In this respect, it will be a major challenge for future work to use diverse cellular progeny of the MPS-iPS cells to study interactions of distinct in vitro–derived cell populations from the same MPS-iPS culture, such as MSC-hematopoietic stem cell, osteocyte-chondrocyte, or glia-neuron, and then to transform this knowledge into therapeutic targeting of tissues (such as bone, cartilage, heart valve, and brain) partially resistant to correction with the current standard allogeneic HCT.42,43

The complexity of MPS IH, as evidenced by the plethora of biochemical events downstream of the IDUA lesion and by the varied phenotypes of human disease, is perhaps matched by the versatility and promise of iPS cell technology. An unresolved question, however, is whether the potential risks of iPS cell–derived therapy, such as those related to (1) genotoxicity of reprogramming with the use of ES cell–specific transcription factors and using viral vectors for gene augmentation of mutated genes,44 (2) fidelity of acquisition and maintenance of pluripotent phenotype and lineage-specific cell fates, and (3) cell purity of the on-demand differentiated iPS cell progeny in the absence of undifferentiated and potentially tumorigenic iPS cells, can be minimized or avoided altogether. Nevertheless, even at present MPS-iPS cells offer a new model of MPS IH disease and may help to understand pathogenic cascades underlying the inherent complexity of MPS IH, including the effect of normal and aberrant GAGs and GAG-containing proteoglycans, which have pivotal roles in cell growth, differentiation, and tissue pattern formation.45–47 These insights, and the use of the cellular progeny of gene-corrected autologous MPS-iPS cells, present an opportunity for future clinical translation in a manner that may preclude the immunologic complications of allogeneic transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Angel Raya, Konrad Hochedlinger, and Ilze Matise for valuable advice and Megan Riddle, Marianna Wong, Jess Lorenz, Trevor Keyler, and Pavlina Chuntova for preparing laboratory data.

This work was supported by the Children's Cancer Research Fund, MN, and by National Institutes of Health grants R21 A1079755 (J.T.), AI081918 (B.R.B.), and P01 CA067493 (B.R.B.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.T. designed the research project, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; I.-H.P., L.X., C.J.L., B.P., B.W., R.T.M., and C.R.E. performed experiments; P.J.O., M.K., M.J.O., T.C.L., and J.E.W. provided essential advice and analyzed the data; G.Q.D. and B.R.B. contributed to the study design and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jakub Tolar, Blood and Marrow Transplant Program; 420 Delaware St SE, MMC 366, Minneapolis, MN 55455; e-mail: tolar003@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Fratantoni JC, Hall CW, Neufeld EF. Hurler and Hunter syndromes: mutual correction of the defect in cultured fibroblasts. Science. 1968;162(853):570–572. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3853.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobbs JR, Hugh-Jones K, Barrett AJ, et al. Reversal of clinical features of Hurler's disease and biochemical improvement after treatment by bone-marrow transplantation. Lancet. 1981;2(8249):709–712. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orchard PJ, Blazar BR, Wagner J, Charnas L, Krivit W, Tolar J. Hematopoietic cell therapy for metabolic disease. J Pediatr. 2007;151(4):340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakkis ED, Muenzer J, Tiller GE, et al. Enzyme-replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis I. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(3):182–188. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krivit W, Sung JH, Shapiro EG, Lockman LA. Microglia: the effector cell for reconstitution of the central nervous system following bone marrow transplantation for lysosomal and peroxisomal storage diseases. Cell Transplant. 1995;4(4):385–392. doi: 10.1177/096368979500400409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy DW, Abkowitz JL. Kinetics of central nervous system microglial and macrophage engraftment: analysis using a transgenic bone marrow transplantation model. Blood. 1997;90(3):986–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mildner A, Schmidt H, Nitsche M, et al. Microglia in the adult brain arise from Ly-6ChiCCR2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(12):1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/nn2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simard AR, Rivest S. Bone marrow stem cells have the ability to populate the entire central nervous system into fully differentiated parenchymal microglia. FASEB J. 2004;18(9):998–1000. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1517fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boelens JJ, Rocha V, Aldenhoven M, et al. Risk factor analysis of outcomes after unrelated cord blood transplantation in patients with hurler syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(5):618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters C, Shapiro EG, Anderson J, et al. Hurler syndrome: II. Outcome of HLA-genotypically identical sibling and HLA-haploidentical related donor bone marrow transplantation in fifty-four children. The Storage Disease Collaborative Study Group. Blood. 1998;91(7):2601–2608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staba SL, Escolar ML, Poe M, et al. Cord-blood transplants from unrelated donors in patients with Hurler's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1960–1969. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill S, Olson JA, Negrin RS. Natural killer cells in allogeneic transplantation: effect on engraftment, graft-versus-tumor, and graft-versus-host responses. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(7):765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451(7175):141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scharf SJ, Smith AG, Hansen JA, McFarland C, Erlich HA. Quantitative determination of bone marrow transplant engraftment using fluorescent polymerase chain reaction primers for human identity markers. Blood. 1995;85(7):1954–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan EM, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Park IH, et al. Live cell imaging distinguishes bona fide human iPS cells from partially reprogrammed cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(11):1033–1037. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freberg CT, Dahl JA, Timoskainen S, Collas P. Epigenetic reprogramming of OCT4 and NANOG regulatory regions by embryonal carcinoma cell extract. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(5):1543–1553. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paruzynski A, Arens A, Gabriel R, et al. Genome-wide high-throughput integrome analyses by nrLAM-PCR and next-generation sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(8):1379–1395. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aasen T, Raya A, Barrero MJ, et al. Efficient and rapid generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human keratinocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(11):1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Rigamonti A, Utikal J, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K. A high-efficiency system for the generation and study of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhjan RK, Lalykina KS. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1970;3(4):393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1970.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prockop DJ. Repair of tissues by adult stem/progenitor cells (MSCs): controversies, myths, and changing paradigms. Mol Ther. 2009;17(6):939–946. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair—current views. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murata H, Janin A, Leboeuf C, et al. Donor-derived cells and human graft-versus-host disease of the skin. Blood. 2007;109(6):2663–2665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tolar J, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Riddle M, et al. Amelioration of epidermolysis bullosa by transfer of wild-type bone marrow cells. Blood. 2009;113(5):1167–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-161299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134(5):877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science. 2008;322(5903):949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1164270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raya A, Rodriguez-Piza I, Guenechea G, et al. Disease-corrected haematopoietic progenitors from Fanconi anaemia induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;460(7251):53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature08129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wynn RF, Wraith JE, Mercer J, et al. Improved metabolic correction in patients with lysosomal storage disease treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplant compared with enzyme replacement therapy. J Pediatr. 2009;154(4):609–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng Q, Lu SJ, Klimanskaya I, et al. Hemangioblastic derivatives from human induced pluripotent stem cells exhibit limited expansion and early senescence. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):704–712. doi: 10.1002/stem.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartung SD, Frandsen JL, Pan D, et al. Correction of metabolic, craniofacial, and neurologic abnormalities in MPS I mice treated at birth with adeno-associated virus vector transducing the human alpha-L-iduronidase gene. Mol Ther. 2004;9(6):866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng Y, Ryazantsev S, Ohmi K, et al. Retrovirally transduced bone marrow has a therapeutic effect on brain in the mouse model of mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;82(4):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desnick RJ, Thorpe SR, Fiddler MB. Toward enzyme therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Physiol Rev. 1976;56(1):57–99. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1976.56.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walkley SU. Pathogenic cascades in lysosomal disease-Why so complex? J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32(2):181–189. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-1040-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan C, Nelson MS, Reyes M, et al. Functional abnormalities of heparan sulfate in mucopolysaccharidosis-I are associated with defective biologic activity of FGF-2 on human multipotent progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106(6):1956–1964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan SA, Nelson MS, Pan C, Gaffney PM, Gupta P. Endogenous heparan sulfate and heparin modulate bone morphogenetic protein-4 signaling and activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294(6):C1387–1397. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00346.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callahan JW, Bagshaw RD, Mahuran DJ. The integral membrane of lysosomes: its proteins and their roles in disease. J Proteomics. 2009;72(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tulpule A, Lensch MW, Miller JD, et al. Knockdown of Fanconi anemia genes in human embryonic stem cells reveals early developmental defects in the hematopoietic lineage. Blood. 2010;115(17):3453–3462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng XL, Shen JS, Kawagoe S, Ohashi T, Brady RO, Eto Y. Induced pluripotent stem cells derived from mouse models of lysosomal storage disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(17):7886–7891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002758107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D, Zhang W, Kalfa TA, et al. Reprogramming erythroid cells for lysosomal enzymeproduction leads to visceral and CNS cross-correction in mice with Hurler syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(47):19958–19963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908528106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braunlin E, Mackey-Bojack S, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Cardiac functional and histopathologic findings in humans and mice with mucopolysaccharidosis type I: implications for assessment of therapeutic interventions in hurler syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(1):27–32. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000190579.24054.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson S, Hashamiyan S, Clarke L, et al. Glycosaminoglycan-mediated loss of cathepsin K collagenolytic activity in MPS I contributes to osteoclast and growth plate abnormalities. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(5):2053–2062. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kohn DB, Sadelain M, Glorioso JC. Occurrence of leukaemia following gene therapy of X-linked SCID. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(7):477–488. doi: 10.1038/nrc1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gandhi NS, Mancera RL. The structure of glycosaminoglycans and their interactions with proteins. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;72(6):455–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambaerts K, Wilcox-Adelman SA, Zimmermann P. The signaling mechanisms of syndecan heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(5):662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodgers KD, San Antonio JD, Jacenko O. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans: a GAGgle of skeletal-hematopoietic regulators. Dev Dyn. 2008;237(10):2622–2642. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuhn RM, Karolchik D, Zweig AS, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser Database: update 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D755–761. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.