Abstract

The ability to traverse an intact nuclear envelope and productively infect non-dividing cells is a salient feature of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and other lentiviruses, but the viral factors and mechanism of nuclear entry have not been defined. We have recently reported a functional role for the nucleoporin NUP153 in the nuclear import of the HIV-1 preintegration complex (PIC). Our findings suggest that HIV-1 sub-viral particles gain access to the nucleus by interacting directly with the nuclear pore complex (NPC) via the binding of PIC-associated integrase (IN) to the C-terminal domain of NUP153. This article discusses how NPC conformation and constitution might influence nuclear import of the PIC, and the subsequent integration of the viral cDNA into actively transcribed genes.

Key words: human immunodeficiency virus type 1, integrase, nuclear import, nuclear pore complex, nucleoporin, NUP153, preintegration complex

The Nuclear Pore Complex: A New Dynamic in HIV-1 Replication

Retroviruses are a family of viruses that are obligated to complete part of their life cycle in the nucleus. After cell entry and uncoating, the viral RNA genome is reverse transcribed into cDNA, which is then assembled along with viral and cellular proteins into a large nucleoprotein complex termed the pre-integration complex (PIC). The PIC is then transported into the nucleus of the newly infected cell where the viral genome is integrated into the cellular chromosomal DNA through the catalytic activity of the viral enzyme IN. Integration is an essential step in the viral life-cycle;1 in the absence of integration, production of progeny virus is inefficient and spreading infection is not realized. Integration of the viral cDNA represents a permanent modification of the cellular genetic content for the infected cell that will be replicated in subsequent daughter cells. For most members of the retroviral family of viruses, access to the nucleus is cell cycle dependent and coincides with the breakdown of the nuclear envelope during mitosis. In contrast, lentiviruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1), simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), comprise a sub-family of retroviruses that distinguish themselves based on their ability to productively infect terminally differentiated and non-dividing cells. This feature of lentiviral infection suggests that the lentiviral PIC can traverse an intact nuclear envelope. Although the infection of non-dividing cells such as macrophage and quiescent T-cells contributes to the pathophysiology of HIV-1 and the development of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), this same biological characteristic also drives the development of lentiviruses as gene therapy vectors for use in non-dividing and terminally differentiated cells, such as neurons, lung and muscle cells.

Nuclear Import of the Lentiviral PIC: An Enduring Question

While infection of non-dividing cells is a striking feature of lentiviruses, the precise mechanism by which the lentiviral PIC is transported across the nuclear envelope and delivered into the nucleus continues to elude characterization. As indicated earlier, the impetus for better understanding the nuclear import of the PIC is due in part to the essential nature of this step in the viral life cycle. Developing antiviral compounds that disrupt PIC nuclear import may represent an effective therapeutic intervention to treat HIV infection and AIDS. Also, in the context of gene therapy applications using lentiviral vectors, nuclear delivery and integration of the vector genome are essential for expression of the therapeutic gene product. Modulating this step to enhance vector efficiency and control nuclear targeting represent valid aims in gene therapy vector design.

The PIC is a large complex with a Stokes radius estimated at 28 nm and the sedimentation coefficient at around 640S,2 and is therefore unlikely to passively diffuse across the nuclear envelope; instead, experimental evidence suggest that the PIC is actively transported into the nucleus.3 The classical model of active nuclear import in the cell4 illustrates a process by which proteins destined for the nucleus are identified by the presence of a nuclear localization sequence (NLS). When the NLS is recognized and bound by a member of the importin family of nuclear import receptors, the resulting import complex translocates into the nucleus. The RAN-GDP/RAN-GTP gradient that exists between the cytoplasm and nucleus serves to drive the direction of transport, and to recycle the receptors once an import cycle is complete. Movement of import complexes into the nucleus occurs through nuclear pore complexes (NPCs), aqueous channels that traverse the nuclear envelope. Despite considerable effort to demonstrate a role for nuclear import receptors and classical import pathways during PIC nuclear import, there is no clear evidence that these factors are essential for the transport of the viral complex.3 The potential role of the NPC in the active transport of the PIC remains largely unknown. However, increasing evidence suggest that the NPC may directly mediate the active nuclear import of proteins that are transported independently of the canonical receptor-dependent import pathways. A closer look at the role of the NPC in PIC nuclear transport may offer clarification of long-standing questions regarding this critical step in the viral life-cycle.

The Dynamic NPC and Nuclear Import of the PIC

The NPC comprises numerous proteins (nucleoporins; NUPs) that assemble to form the larger pore complex. For molecules and ions that are sufficiently small (25–40 kDa),5 passive diffusion through the NPC channel is possible. However, the NPC is impervious to larger molecules and complexes in the absence of an active transport mechanism. As a result of its “gate-like” characteristic, the NPC represents an important level of regulation governing exchanges that take place between the nucleus and cytoplasm. The perception of the NPC as a static structure has largely given way to the understanding of the NPC as a dynamic complex whose conformation is linked with its functional activity.5 Evidence for this dynamic behavior is seen in the variable association of the nucleoporin NUP153 with the NPC. NPC-associated NUP153 can dynamically exchange off the nuclear pore with soluble NUP153 located in the nucleoplasm.6–8 NUP153 also displays variable topology within the NPC during phases of active transport. Both the active import of impβ/impα complexes and active export of mRNA stimulate the movement of the C-terminal domain of NUP153 from the nucleoplasmic face of the NPC to the cytoplasmic face.9 Similar transport-related mobility has also been reported for NUP214 and NUP98,7,9 suggesting that nucleoporin mobility may be a key feature of cargo transport through the NPC.

The absence of strong evidence supporting a role for classical receptor-mediated nuclear import pathways during PIC nuclear import suggests that the lentiviral PIC might employ a novel mechanism for its transport into the nucleus. Non-canonical transport of cellular proteins across the nuclear envelope does occur, and for many such proteins nuclear import is a result of a direct interaction with the NPC,10 most notably with NUP153.11–14 We have recently reported a role for NUP153 in the nuclear transport of the HIV-1 PIC. We have found that the C-terminal domain (amino acid residues 896–1475) of NUP153 is able to interact directly with IN in vitro.15 The presence of excess soluble NUP153 C-terminal domain inhibits the nuclear import of IN in a cell-based nuclear import assay, and cellular factors known to bind to the C-terminal domain of NUP153 compete with IN for binding to NUP153 and also disrupt the nuclear import of IN. Our findings suggest that IN nuclear import is a result of a direct interaction with the C-terminal domain of NUP153. The C-terminal domain of NUP153 that interacts with IN is rich in FxFG repeats, a sequence archetype thought to facilitate nuclear transport of diverse nuclear import complexes by binding to conserved motifs present on importin proteins.16 During nucleocytoplasmic transport, the FxFG repeats provide both a specific but transient binding platform for import complexes, and maintain a significant entropic barrier for passage through the NPC.5 Because IN is a stable component of the PIC, we have proposed that the interaction between the C-terminal domain of NUP153 and PIC-associated IN may help overcome that barrier and contribute to the nuclear import of the virus. In support of this model, we have also observed that ectopic expression of the C-terminal domain of NUP153 inhibits the nuclear translocation of an HIV-1 based vector, presumably by competing with endogenous NUP153 for binding to PIC-associated IN.15 Based on these findings, we have proposed a model of HIV-1 PIC nuclear import in which the NUP153 interaction with IN plays a central role.

Transport of a complex as large as the PIC through the NPC may involve multiple contacts with multiple NUPs, and therefore NUP153 may not be the only NUP involved in the nuclear transport of the PIC. As noted above, NUP214 and NUP98 are mobile NUPs that are actively involved in transport of cargo through the NPC, and have also been identified as key cellular factors in HIV-1 replication.17–19 A direct involvement of NUPs during viral nuclear import is exemplified by the interaction between adenovirus type 2 (Ad2) and NUP214 prior to capsid dissociation and nuclear import of the Ad2 DNA.20 Other roles for NUPs in addition to the nuclear import of the PIC are unknown but represent intriguing lines of investigation, as imaging studies have localized uncoating of the lentiviral core at the NPC.21

In addition to IN, other constituents of the PIC may also contribute to nuclear import by providing stabilizing interactions between the complex and the NPC. The viral protein Vpr has been shown to colocalize with NUPs at the NPC,22 and interacts with NUP153 amino acids 447–634 in the protein's central domain.23 However, the biological significance of this interaction during nuclear import of the PIC is unknown. Since deletion of Vpr from the virus fails to abrogate infection in non-dividing cells,24 the Vpr-NUP153 interaction may not be essential to PIC nuclear import. It is also possible that cellular components of the PIC may contribute to essential interactions between the complex and the NPC. Continued effort to better define the composition of the PIC and its biochemical properties as it migrates through the cytoplasm and across the nuclear envelope may help identify cellular proteins that are essential to this process.

Implications of a Role for NUP153 in PIC Nuclear Import

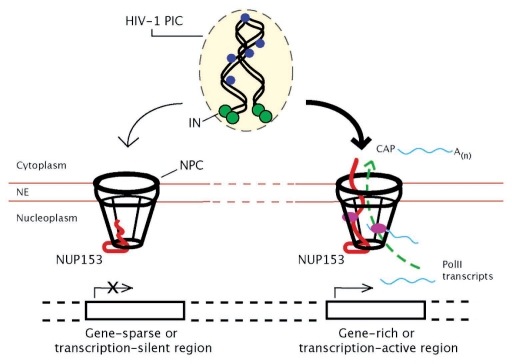

An important aspect of a NUP153-dependent model of PIC nuclear import is the coupling of NUP153 mobility and active transcription.10 Both the dynamic association of NUP153 with the NPC, and the dynamic distribution of the NUP153 C-terminal domain within the NPC are stimulated by active transcription.7,9 Our import model predicts that contact between the C-terminal domain of NUP153 and the PIC is made at the cytoplasmic face of the NPC. Although the N-terminus and central zinc-binding domains of NUP153 are primarily localized to the nuclear basket,25 active transcription results in the dynamic distribution of the C-terminal domain throughout the channel of the NPC, as well as exposure of the domain to the cytoplasm.9 In contrast, transcription inhibition constrains the C-terminus to the nucleoplasmic side of the NPC. Therefore, under conditions of increased transcription, it is predicted that the C-terminal domain of NUP153 would be positioned favorably at the NPC to interact with the incoming PIC and facilitate its nuclear transport (Fig. 1). Because the mobility of the C-terminal domain of NUP153 is largely driven by active transcription and mRNA export, an important implication of this model would then be the preferential transport of the PIC via an interaction with NPCs associated with actively transcribed regions of the genome. Presumably, such NPCs would demonstrate the mobility and conformation of the C-terminal domain of NUP153 necessary to engage the PIC and promote its import.

Figure 1.

A model depicting an active role of the NPC in linking nuclear import of HIV-1 PICs to transcriptionally active genomic regions. The C-terminal domain of NUP153 (in red) is dynamically distributed throughout the aqueous channel of the NPC in a transcription-dependent manner. The transcription-dependent extended conformation of the C-terminal domain of NUP153 can lead to exposure of this domain to the cytoplasm (see the NPC on the right). Active transcription can also drive dynamic exchanges of NPC-associated NUP153 with a soluble nucleoplasm population of NUP153 (not shown). The interaction between PIC-associated IN (green circles) and the extended conformation of the C-terminal domain of NUP153 may represent a key event in the nuclear import of the PIC and subsequent integration of the viral cDNA (black ribbons) into actively transcribed genes. Alternatively, NPCs associated with functionally different genomic regions may contain distinct factors (magenta ovals) that interact specifically with the PIC. Therefore, NPCs associated with transcriptionally active regions of the genome may potentiate nuclear transport of the PIC (indicated with the bold arrow) as a result of conformational and compositional characteristics that are a function of their role in the biogenesis and transport of mRNA. NE, nuclear envelope; blue circles, PIC-associated viral-proteins.

The dynamic association of NUP153 with the NPC6–8 is also reported to be a function of ongoing active transcription, and represents an example of NPC remodeling during RNA export.7 Inhibition of RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) and RNA polymerase I (RNA Pol I) results in NUP153 not being able to release from the NPC to exchange with a nuclear pool of soluble NUP153. Within the context of our model of nuclear import of the PIC, NUP153 that actively exchanges from the NPC may provide a chaperone function to the incoming PIC, resulting in the targeting of the viral complex to chromosomal regions active in transcription.

The hypothesis that PICs are preferentially transported into the nucleus via NPCs that are functionally associated with active transcription and mRNA export is consistent with the observation that HIV-1 favors actively transcribed genes for integration.26 The open chromatin structure that is characteristic of transcription units is thought to be amenable to the integration reaction while condensed DNA within heterochromatin is refractory to integration.27 Integration into such gene-rich and actively transcribed regions of the genome may also serve to benefit viral gene expression, leading to productive infection. In contrast, integration sites within heterochromatin may ultimately suppress viral gene expression and the production of progeny virus.28 A conventional assumption of current research in the area of PIC nuclear import presumes that selection of integration sites is exclusively a post nuclear import event. For instance, targeting of HIV-1 integration to transcription units is partly attributed to the interaction between PIC-associated IN and LEDGF/p75, a global transcription regulator.29 Although LEDGF/p75 is not absolutely required for HIV-1 replication, its deletion leads to a significant reduction in integration events and a shift in integration pattern from a uniform distribution throughout transcription units to one that favors transcription start sites.30–32 Based on our finding that HIV-1 nuclear import requires NUP153 interaction, our model would suggest that selection of transcription units for integration can be influenced by the import of the PIC through an NPC directly coupled with an actively gene or set of genes. This extension of our model is in agreement with the “gene-gating” hypothesis proposed by Blobel,33 which contends that NPCs contribute to the organization of euchromatin by associating with and localizing actively transcribed genes in the vicinity of the nuclear envelope. Experimental evidence demonstrating such a direct role for the NPC in the transcriptional regulation of mammalian genomic loci has been reported.34 The extended conformation of NUP153 characteristic of active transcription and mRNA export may provide a means by which the PIC can “identify” NPCs associated with active transcription. Interacting directly with extended NUP153 offers the PIC a direct link from the cytoplasm to the chromosomal DNA environment best suited to support integration and viral gene expression. Similarly, the interaction of the PIC with NUP153 exchanging from the NPC to areas of active transcription may further direct the PIC to transcription units. The observation that the HIV-1 viral genome preferentially integrates into the chromosomal DNA proximal to the nuclear envelope is consistent with this hypothesis.35

In addition to conformation, NPC composition may also be a factor in the nuclear import of the PIC. NPCs in the same cell may be functionally distinct from one another and differ not only in their conformation, but also with respect to their composition as a result of the functional activity in which they are engaged.5 For example, yeast NPCs that retain the MLP proteins, regulators of mRNA fidelity prior to nuclear export, are found to associate with areas of active mRNA transcription catalyzed by RNA PolII, but not those areas in proximity to the nucleolus, the site of RNA PolI-dependent ribosomal RNA biogenesis.36 The specialization of NPCs has also been reported in mammalian cells.37 NPCs associated with poly(A)+ RNAs are associated with mRNA splicing factors, but not NTF2, a factor for RanGTP-dependent nuclear import. Likewise, NPCs associated with NTF2 are not associated with poly(A)+ RNA. These findings imply that NPCs may contain different NUP-associated proteins as a result of the genomic environment with which the NPCs associate. If NPCs that are functionally and compositionally distinct maintain a different capacity to transport the PIC, then one would expect to see a differential utilization of such functionally distinct NPCs. A possible marker for this phenomenon would be biased integration into functionally distinct genomic regions (Fig. 1). Evidence for this can be derived from the reported bias of HIV-1 to integrate into PolIIdependent transcription units.38 Although PolII does not represent the bulk of cellular transcription, NPCs associated with chromosomal regions hosting PolII transcription may be preferentially targeted by the PIC as a result of the association of factors related to mRNA biogenesis and export. Our model for PIC nuclear import would propose that NPC conformation (i.e., transcription-dependent NUP153 mobility) and NPC composition (i.e., association with functionally distinct cellular factors), are important for targeting the PIC to transcriptionally active regions of the genome for integration.

Conclusions

A more detailed understanding of the mechanisms governing key steps of lentiviral replication is critical to both the discovery of new antiviral drugs to combat HIV-1 infection, and the continued development of lentiviruses as efficient and potent gene therapy vehicles. Perhaps one of the most confounding areas of viral replication that continues to be poorly understood is the mechanism by which the lentiviral genome is transported into the nucleus. A model of PIC nuclear import that considers the NPC as an active agent of nuclear transport may provide an opportunity to assimilate our current knowledge of cellular transcription, viral integration and host cofactors into a better understanding of PIC nuclear transport and the selection of chromosomal integration sites.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/10571

References

- 1.Brown PO. Integration. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 161–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller MD, Farnet CM, Bushman FD. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: Studies of organization and composition. J Virol. 1997;71:5382–5390. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5382-5390.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki Y, Craigie R. The road to chromatin—nuclear entry of retroviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:187–196. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorlich D, Kutay U. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:607–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran EJ, Wente SR. Dynamic nuclear pore complexes: Life on the edge. Cell. 2006;125:1041–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daigle N, Beaudouin J, Hartnell L, Imreh G, Hallberg E, Lippincott-Schwartz J, et al. Nuclear pore complexes form immobile networks and have a very low turnover in live mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:71–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200101089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffis ER, Craige B, Dimaano C, Ullman KS, Powers MA. Distinct functional domains within nucleoporins NUP153 and NUP98 mediate transcription-dependent mobility. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1991–2002. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabut G, Doye V, Ellenberg J. Mapping the dynamic organization of the nuclear pore complex inside single living cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1114–1121. doi: 10.1038/ncb1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulillo SM, Phillips EM, Koser J, Sauder U, Ullman KS, Powers MA, et al. Nucleoporin domain topology is linked to the transport status of the nuclear pore complex. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:784–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ball JR, Ullman KS. Versatility at the nuclear pore complex: Lessons learned from the nucleoporin NUP153. Chromosoma. 2005;114:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitehurst AW, Wilsbacher JL, You Y, Luby-Phelps K, Moore MS, Cobb MH. Erk2 enters the nucleus by a carrier-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7496–7501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112495999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marg A, Shan Y, Meyer T, Meissner T, Brandenburg M, Vinkemeier U. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling by nucleoporins NUP153 and NUP214 and CRM1-dependent nuclear export control the subcellular distribution of latent Stat1. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:823–833. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong H, Takeda A, Nazari R, Shio H, Blobel G, Yaseen NR. Carrier-independent nuclear import of the transcription factor PU.1 via RanGTP-stimulated binding to NUP153. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10675–10682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu L, Kang Y, Col S, Massague J. Smad2 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling by nucleoporins CAN/NUP214 and NUP153 feeds TGFbeta signaling complexes in the cytoplasm and nucleus. Mol Cell. 2002;10:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodward CL, Prakobwanakit S, Mosessian S, Chow SA. Integrase interacts with nucleoporin NUP153 to mediate the nuclear import of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2009;83:6522–6533. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02061-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayliss R, Littlewood T, Stewart M. Structural basis for the interaction between FXFG nucleoporin repeats and importin-beta in nuclear trafficking. Cell. 2000;102:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebina H, Aoki J, Hatta S, Yoshida T, Koyanagi Y. Role of NUP98 in nuclear entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNA. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, Yan N, Engelman A, Xavier RJ, et al. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319:921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konig R, Zhou Y, Elleder D, Diamond TL, Bonamy GM, Irelan JT, et al. Global analysis of host-pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell. 2008;135:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greber UF, Fassati A. Nuclear import of viral DNA genomes. Traffic. 2003;4:136–143. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arhel NJ, Souquere-Besse S, Munier S, Souque P, Guadagnini S, Rutherford S, et al. HIV-1 DNA flap formation promotes uncoating of the pre-integration complex at the nuclear pore. EMBO J. 2007;26:3025–3037. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vodicka MA, Koepp DM, Silver PA, Emerman M. HIV-1 Vpr interacts with the nuclear transport pathway to promote macrophage infection. Genes Dev. 1998;12:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varadarajan P, Mahalingam S, Liu P, Ng SB, Gandotra S, Dorairajoo DS, et al. The functionally conserved nucleoporins NUP124p from fission yeast and the human NUP153 mediate nuclear import and activity of the Tf1 retrotransposon and HIV-1 Vpr. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1823–1838. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kootstra NA, Schuitemaker H. Phenotype of HIV-1 lacking a functional nuclear localization signal in matrix protein of gag and Vpr is comparable to wild-type HIV-1 in primary macrophages. Virology. 1999;253:170–180. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahrenkrog B, Maco B, Fager AM, Koser J, Sauder U, Ullman KS, et al. Domain-specific antibodies reveal multiple-site topology of NUP153 within the nuclear pore complex. J Struct Biol. 2002;140:254–267. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bushman F, Lewinski M, Ciuffi A, Barr S, Leipzig J, Hannenhalli S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of retroviral DNA integration. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang GP, Ciuffi A, Leipzig J, Berry CC, Bushman FD. HIV integration site selection: Analysis by massively parallel pyrosequencing reveals association with epigenetic modifications. Genome Res. 2007;17:1186–1194. doi: 10.1101/gr.6286907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewinski MK, Bisgrove D, Shinn P, Chen H, Hoffmann C, Hannenhalli S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal features repressing human immunodeficiency virus transcription. J Virol. 2005;79:6610–6619. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6610-6619.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelman A, Cherepanov P. The lentiviral integrase binding protein LEDGF/p75 and HIV-1 replication. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:1000046. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciuffi A, Llano M, Poeschla E, Hoffmann C, Leipzig J, Shinn P, et al. A role for LEDGF/p75 in targeting HIV DNA integration. Nat Med. 2005;11:1287–1289. doi: 10.1038/nm1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Llano M, Saenz DT, Meehan A, Wongthida P, Peretz M, Walker WH, et al. An essential role for LEDGF/p75 in HIV integration. Science. 2006;314:461–464. doi: 10.1126/science.1132319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shun M-C, Raghavendra NK, Vandegraaff N, Daigle JE, Hughes S, Kellam P, et al. LEDGF/p75 functions downstream from preintegration complex formation to effect gene-specific HIV-1 integration. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1767–1778. doi: 10.1101/gad.1565107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blobel G. Gene gating: A hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8527–8529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown CR, Kennedy CJ, Delmar VA, Forbes DJ, Silver PA. Global histone acetylation induces functional genomic reorganization at mammalian nuclear pore complexes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:627–639. doi: 10.1101/gad.1632708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albanese A, Arosio D, Terreni M, Cereseto A. HIV-1 pre-integration complexes selectively target decondensed chromatin in the nuclear periphery. PLoS One. 2008;3:2413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galy V, Gadal O, Fromont-Racine M, Romano A, Jacquier A, Nehrbass U. Nuclear retention of unspliced mRNAs in yeast is mediated by perinuclear Mlp1. Cell. 2004;116:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iborra FJ, Jackson DA, Cook PR. The path of RNA through nuclear pores: Apparent entry from the sides into specialized pores. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:291–302. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]