Abstract

Retroviruses integrate their genome into the chromatin of the host cell and are subject to the same control mechanisms governing transcription in the nucleus. There is increasing evidence that the spatial position of a gene within the nucleus in time affects its activity. Therefore it becomes important to study the chromatin environment in space and time of the HIV-1 provirus, particularly in cells where a tight transcriptional control allows the virus to hide away from antiviral treatment and immune response. We recently showed that the HIV-1 provirus is found at the nuclear periphery of latently infected lymphocytes associated in trans with centromeric heterochromatin. After induction of transcription, this association was lost, although the location of the transcribing provirus remained peripheral. Our results reveal a novel mechanism of transcriptional silencing involved in HIV-1 post-transcriptional latency and open wider perspectives for the general organization of chromatin in the nucleus.

Key words: chromatin, nucleus, HIV, latency, transcription

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a retrovirus and the hallmark of this family of viruses is their ability to retro-transcribe their RNA genomes into DNA that is then transported into the nucleus and integrated into chromatin.1 The nucleus is highly organized, with distinct chromosome territories occupying specific positions, and a variety of subnuclear domains.2,3 Most of them are transiently assembled for a specific function, for example transcription occurs in ‘factories’ where genes and the RNA polymerase complex assemble.4,5 The prototype ‘transcription factory’ of the nucleus is the nucleolus where rRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase I, but several other RNA polymerase II foci are scattered in the nucleoplasm at a given time. Recent advances of in vivo—imaging approaches revealed that most protein-DNA interactions are transient with rapid cycles of binding, unbinding and free diffusion in the nucleoplasm.6,7 Also genes move within the nucleoplasm forming loops that spatially segregate genome regions from each other and allow their independent function (i.e., transcriptional activation or repression).8–10 Therefore most processes in the nucleus are stochastic events governed by probabilistic laws and the spatial organization of genes in time within the nucleus has regulatory potential over their activity. What happens when an exogenous novel transcription unit, like a retroviral gene becomes part of this complex architecture? What kind of transcriptional control is imposed by the nuclear organization of the host over virus transcription? Answers to these questions are important both for our understanding of viral replication and of the cellular mechanisms involved in the process.

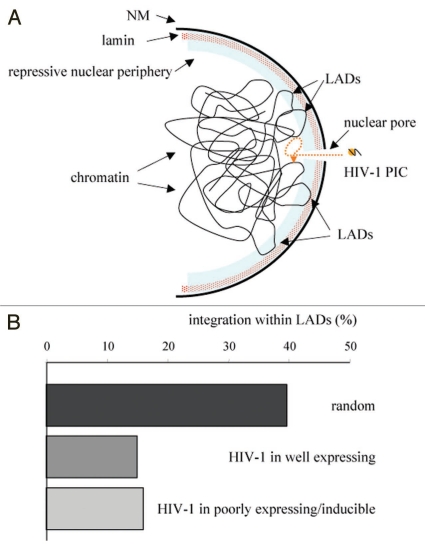

Nuclear import and integration of HIV-1 DNA are mitosis-independent in cycling cells. The pre-integration complex (PIC) containing retro-transcribed viral DNA and the viral integrase must cross the nuclear pore and overcome the steep DNA concentration gradient in the nucleus.11 Consequently integration is more likely to occur in the proximity of the nuclear periphery rather than towards the interior of the nucleus, as long as a favorable integration site is found (Fig. 1A). We and others observed that the HIV-1 pre-integration complex selectively targets open chromatin at the nuclear periphery.12 We also have observed that in several cell lines carrying an integrated latent provirus the localization was close to the nuclear periphery.13 However, the locus remained peripheral both in the inactive and in the active state ruling out a direct silencing imposed by the periphery of the nucleus per se. This finding seems to argue against recent data showing that artificial tethering of a genomic locus to the nuclear lamina may result in transcriptional repression, albeit not absolute.14,15 In yeast, the nuclear periphery is comprised of at least two sub-compartments: a repressive compartment and a permissive compartment involving nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) that facilitates gene expression locally.16,17 In addition, a third set of tethering experiments in mammalian cells showed active transcription at that location.18 Therefore, we conclude that either HIV-1 integration at the nuclear periphery overcomes repression or there are domains permissive for transcription that HIV-1 can target specifically.

Figure 1.

(A) A schematic representation of the early steps of HIV-1 integration. The HIV-1 preintegration complex (PIC) travels through the pore of the infected cell's nucleus. The steep chromatin concentration gradient that the PIC encounters restricts the choice of the integration site to a peripheral localization. Integration at the inner nuclear membrane (NM) within the repressive compartment defined by the lamin and the lamin-associated domains (LADs) is disfavored. Integration into active genes and open chromatin is instead favored. (B) HIV-1 integration into LADs is disfavored. The integration sites of (i) cell carrying a proviral vector that is well-expressing (n = 587) and (ii) cells carrying an integrations site that is poorly expressing but inducible (n = 384) derived from Lewinski et al.20 are compared to random integrations (100 iterations of n = 500) for their association to lamin associated domains (LADs) as defined in Guelen et al.19

Recently the group of Bas van Stenseel reported a high-resolution map of the interaction sites of the entire human genome with the nuclear lamina.19 These lamin-associated domains (LADs) represent a repressive chromatin environment tightly associated to the nuclear periphery. We were curious to see if there was a correlation between the integration sites of HIV-1 and LADs. Therefore we took advantage of two libraries of integration sites generated in the laboratory of Frederic D. Bushman.20 One set of integration sites was derived from cells that expressed the provirus constitutively, the other from cells that expressed the provirus poorly but could be reactivated by TNFα, an agent that is known to activate LTR transcription. The latter represent latently infected cells and are particularly relevant to HIV-1 persistence during antiviral therapy.21 Interestingly, we noted that in both cases integration within LADs was equally disfavored compared to randomly generated integration sites (Fig. 1B). Hence, repressive chromatin domains in tight conjunction with the nuclear lamina are not favorable sites for HIV-1 integration. This is consistent with the observation that HIV-1 integrated preferentially within active genes20,22 and active genes are also enriched outside LADs.19 Since, the analysis in Figure 1B was conducted on different human cell types (fibroblasts and lymphocytes) that may differ in the organization of the nucleus, it will be important to confirm these data in the same cellular background, possibly from latently infected patients. Nevertheless, the emerging picture is that HIV-1 integrates preferentially at the nuclear periphery within active genes that are loosely associated to the nuclear lamina.

An interesting question is whether there are going to be differences in the positioning of the integration site between cells carrying a highly expressing HIV-1 virus and cells carrying a latent-but- inducible virus. This is critical for our understanding of viral post-integration latency because all the processes that induce silencing of the provirus also allow the virus to hide from antiviral therapy and relapse after discontinuation of treatment, even after several years.21 Although yet to be formally proven, we wouldn't expect differences in the radial positioning of the provirus in latent versus actively transcribing cells. However, we expect differences with respect to the microenvironment of the integration site. In the case of constitutive virus expression, chromatin has to be open and permissive, while in the case of a latent infection it is expected to be open and permissive initially to allow integration, but then the provirus has to be silenced remaining inducible by external stimuli. This happens in cell types like resting memory T cells by a combination of various mechanisms: (1) the availability of factors essential for transcription;23 (2) transcriptional interference from the endogenous gene harboring the provirus;24–26 (3) formation of heterochromatin at the site of provirus integration;27 (4) CpG methylation of the HIV-1 promoter;28,29 (5) post-transcriptional mechanisms.30–32 Our studies indicate another level of control determined by the three-dimensional conformation of chromatin at the provirus that we may call (6) silencing in trans as described below.

The transition from active genes permissive to HIV-1 integration to transiently silenced chromatin may depend on the changes in chromatin organization of infected CD4+ lymphoblasts that have reverted to a resting memory state. However this process is challenging to reconstruct in vitro and only recently Alberto Bosque and Vicente Planelles described an ex vivo experimental system that generates high levels of HIV-1 latently infected memory cells using primary CD4+ T cells.33 Using a simplified model of a lymphoblastoid cell line carrying a single HIV-1 latent vector we were able to demonstrate that in the silenced state the provirus was associated in trans with a pericentromeric region of another chromosome at the periphery of the nucleus.13 Interestingly, this association was lost upon transcriptional activation, although the provirus remained peripheral also during active transcription. We noticed, however, that in the latent state only a fraction of nuclei showed this association in trans, indicating that there are different and alternative levels of silencing. We defined as the ‘off-off state’ the situation where the provirus is associated to alphoid-repeats in trans and is affected by the silencing environment at the centromere. We call the ‘off state’ the condition of the remaining latently infected cells that are not subject to trans-silencing and may already be poised for transcription. The latter type of regulation of a retroviral gene at a single locus may be similar to that of inactive genes located in open chromatin.34 A provirus already poised for transcription may carry a stalled RNA polymerase II that requires an exogenous stimulus to start elongating. But how does the transition from the ‘off-off state’ to the ‘off state’ occur? We expect that a physical interaction between genes must be disrupted. One possibility is that passage through mitosis is required to re-organize chromatin at the proviral locus.35 However, in our system, treatment of leukaemic T cell lines with phorbol esters used to trigger HIV transcription induces growth arrest in G1 and does not therefore require mitosis.36 Alternatively, the exogenous signal itself may trigger the modification of the locus, or simply the ‘off-off state’ and ‘off state’ are in a dynamic equilibrium that is shifted by transcriptional activation. The latter hypothesis is intriguing since it requires active and coordinated movement of genomic loci and association/dissociation of factors throughout interphase. Clearly chromosome territories occupy defined subnuclear positions, but there is a lot of intermingling between them.37 Novel techniques that allow high resolution imaging of several taggable endogenous loci in living cells are required to address ‘dynamic intermingling’ between chromosome territories during interphase. To this end we have developed an HIV-1 vector carrying the binding sites for the MS2 phage core protein fused to GFP.38 This method allowed us to measure both the rate of elongation of RNA polymerase II and the residence time of transcription factors at the retroviral gene, including RNAPII itself, the viral transactivator Tat and the transcription kinase CDK9.38,39 The emerging picture from these studies is that HIV-1 integrates close to the nuclear periphery and in active genes where it is generally transcriptionally competent. In some cells the provirus is silenced, either irreversibly or reversibly, the latter state being critical for viremic relapse. Reversible silencing must depend on a physical modification of the chromatin environment that may occur during by the shift from active to resting of memory T cells, with the provirus being passively trapped in a silenced genomic locus. This status may be considered as a dynamic equilibrium between inactive and activated provirus where the latter is under negative selective pressure by the antiviral treatment. Upon discontinuation of therapy and/or exogenous activation signals the equilibrium is shifted towards transcription. This process is extremely potent for HIV-1, particularly when the viral Tat transactivator reaches the levels that trigger a positive-feedback circuit.40 Active HIV-1 gene appears to be locked in a transcription state by gene looping that link the 5′ and 3′-end of the provirus.41

We conclude that studies on HIV-1 are instrumental for our understanding of nuclear organization and transcription, providing general concepts that can be extended to the regulation of other genes.

Acknowledgements

Our work is supported by a HFSP Young Investigators Grant, by the Italian FIRB program of the Ministero dell'Istruzione, Università e Ricerca of Italy, by the EC FP6 STREP project n. n. 012182 and by the AIDS Program of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità of Italy.

Abbreviations

- HIV-1

human immunedeficiency virus type 1

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- PIC

pre-integration complex

- NPC

nuclear pore complex

- LAD

lamin-associated domains

- CD4

cluster of differentiation 4 (glycoprotein)

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- RNPII

RNA polymerase II

- CDK9

cyclin-dependent kinase 9

- NM

nuclear membrane

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/10136

References

- 1.Greene WC, Peterlin BM. Charting HIV's remarkable voyage through the cell: Basic science as a passport to future therapy. Nat Med. 2002;8:673–680. doi: 10.1038/nm0702-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misteli T. Spatial positioning; a new dimension in genome function. Cell. 2004;119:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spector DL. Nuclear domains. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2891–2893. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook PR. The organization of replication and transcription. Science. 1999;284:1790–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakalova L, Debrand E, Mitchell JA, Osborne CS, Fraser P. Replication and transcription: shaping the landscape of the genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:669–677. doi: 10.1038/nrg1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misteli T. Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell. 2007;128:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sexton T, Schober H, Fraser P, Gasser SM. Gene regulation through nuclear organization. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1049–1055. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Driel R, Fransz PF, Verschure PJ. The eukaryotic genome: a system regulated at different hierarchical levels. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4067–4075. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser P. Transcriptional control thrown for a loop. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cremer T, Cremer M, Dietzel S, Muller S, Solovei I, Fakan S. Chromosome territories—a functional nuclear landscape. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fassati A. HIV infection of non-dividing cells: a divisive problem. Retrovirology. 2006;3:74. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albanese A, Arosio D, Terreni M, Cereseto A. HIV-1 pre-integration complexes selectively target decondensed chromatin in the nuclear periphery. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:2413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dieudonne M, Maiuri P, Biancotto C, Knezevich A, Kula A, Lusic M, et al. Transcriptional competence of the integrated HIV-1 provirus at the nuclear periphery. EMBO J. 2009;28:2231–2243. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature. 2008;452:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finlan LE, Sproul D, Thomson I, Boyle S, Kerr E, Perry P, et al. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:1000039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrulis ED, Neiman AM, Zappulla DC, Sternglanz R. Perinuclear localization of chromatin facilitates transcriptional silencing. Nature. 1998;394:592–595. doi: 10.1038/29100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taddei A, Van Houwe G, Hediger F, Kalck V, Cubizolles F, Schober H, et al. Nuclear pore association confers optimal expression levels for an inducible yeast gene. Nature. 2006;441:774–778. doi: 10.1038/nature04845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumaran RI, Spector DL. A genetic locus targeted to the nuclear periphery in living cells maintains its transcriptional competence. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:51–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453:948–951. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewinski MK, Bisgrove D, Shinn P, Chen H, Hoffmann C, Hannenhalli S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal features repressing human immunodeficiency virus transcription. J Virol. 2005;79:6610–6619. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6610-6619.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcello A. Latency: the hidden HIV-1 challenge. Retrovirology. 2006;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcello A, Ferrari A, Pellegrini V, Pegoraro G, Lusic M, Beltram F, et al. Recruitment of human cyclin T1 to nuclear bodies through direct interaction with the PML protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:2156–2166. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han Y, Lin YB, An W, Xu J, Yang HC, O'Connell K, et al. Orientation-dependent regulation of integrated HIV-1 expression by host gene transcriptional readthrough. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenasi T, Contreras X, Peterlin BM. Transcriptional interference antagonizes proviral gene expression to promote HIV latency. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Marco A, Biancotto C, Knezevich A, Maiuri P, Vardabasso C, Marcello A. Intragenic transcriptional cis-activation of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 does not result in allele-specific inhibition of the endogenous gene. Retrovirology. 2008;5:98. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.du Chene I, Basyuk E, Lin YL, Triboulet R, Knezevich A, Chable-Bessia C, et al. Suv39H1 and HP1gamma are responsible for chromatin-mediated HIV-1 transcriptional silencing and post-integration latency. EMBO J. 2007;26:424–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kauder SE, Bosque A, Lindqvist A, Planelles V, Verdin E. Epigenetic regulation of HIV-1 latency by cytosine methylation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:1000495. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blazkova J, Trejbalova K, Gondois-Rey F, Halfon P, Philibert P, Guiguen A, et al. CpG methylation controls reactivation of HIV from latency. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:1000554. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lassen KG, Ramyar KX, Bailey JR, Zhou Y, Siliciano RF. Nuclear retention of multiply spliced HIV-1 RNA in resting CD4+ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:68. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, Chen K, Liang Z, Tian H, et al. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Med. 2007;13:1241–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chable-Bessia C, Meziane O, Latreille D, Triboulet R, Zamborlini A, Wagschal A, et al. Suppression of HIV-1 replication by microRNA effectors. Retrovirology. 2009;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosque A, Planelles V. Induction of HIV-1 latency and reactivation in primary memory CD4+ T cells. Blood. 2009;113:58–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbert N, Boyle S, Fiegler H, Woodfine K, Carter NP, Bickmore WA. Chromatin architecture of the human genome: gene-rich domains are enriched in open chromatin fibers. Cell. 2004;118:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson I, Gilchrist S, Bickmore WA, Chubb JR. The radial positioning of chromatin is not inherited through mitosis but is established de novo in early G1. Curr Biol. 2004;14:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boonen GJ, van Oirschot BA, van Diepen A, Mackus WJ, Verdonck LF, Rijksen G, et al. Cyclin D3 regulates proliferation and apoptosis of leukemic T cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34676–34682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Branco MR, Pombo A. Intermingling of chromosome territories in interphase suggests role in translocations and transcription-dependent associations. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boireau S, Maiuri P, Basyuk E, de la Mata M, Knezevich A, Pradet-Balade B, et al. The transcriptional cycle of HIV-1 in real-time and live cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:291–304. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molle D, Maiuri P, Boireau S, Bertrand E, Knezevich A, Marcello A, et al. A real-time view of the TAR:Tat:P-TEFb complex at HIV-1 transcription sites. Retrovirology. 2007;4:36. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinberger LS, Burnett JC, Toettcher JE, Arkin AP, Schaffer DV. Stochastic Gene Expression in a Lentiviral Positive-Feedback Loop: HIV-1 Tat Fluctuations Drive Phenotypic Diversity. Cell. 2005;122:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkins KJ, Lusic M, Mitar I, Giacca M, Proudfoot NJ. Transcription-dependent gene looping of the HIV-1 provirus is dictated by recognition of premRNA processing signals. Mol Cell. 2008;29:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]