Abstract

About 3,000 new citations that are highly similar to citations in previously published manuscripts that appear each year in the biomedical literature (Medline) alone. This underscores the importance for the opportunity for editors and reviewers to have detection system to identify highly similar text in submitted manuscripts so that they can then review them for novelty. New software-based services, both commercial and free, provide this capability. The availability of such tools provides both a way to intercept suspect manuscripts and serve as a deterrent. Unfortunately, the capabilities of these services vary considerably, mainly as a consequence of the availability and completeness of the literature bases to which new queries are compared. Most of the commercial software has been designed for detection of plagiarism in high school and college papers, however, there is at least one fee-based service (CrossRef) and one free service (etblast.org) which are designed to target the needs of the biomedical publication industry. Information on these various services, examples of the type of operability and output, and things that need to be considered by publishers, editors and reviewers before selecting and using these services is provided.

Introduction

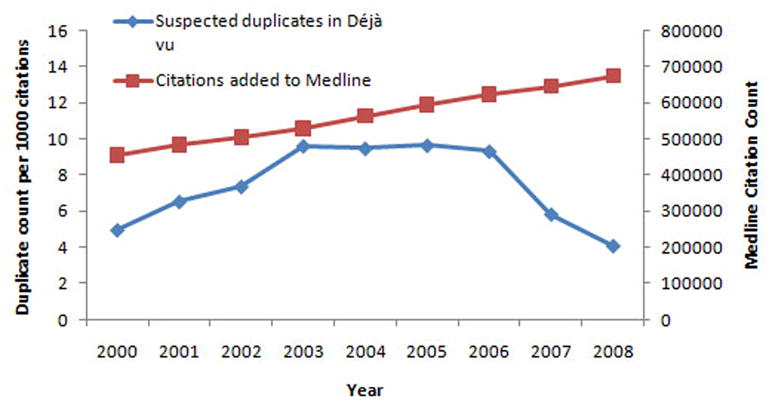

Ethically questionable highly similar manuscripts whether they are from the same authors (duplicate publication) or from different authors (plagiarized publication) contribute little or negatively impact society.1 When this negative impact is in the scientific domain, and especially if it is in the clinical domain, there can result in harm: scientists or clinicians can use the data to make research or patient judgments that are wrong, editors and reviewer use their valuable time to review these manuscripts, and the lay public questions the quality of science and medicine when major public revelations of misbehavior surface. It is important to identify, intercept and eliminate these unethical submissions as early in the publication process as possible, certainly before they become part of the scientific record, where their removal can be difficult. Over the years, with more papers appearing electronically2 and with it becoming easier to cut/paste text, manipulate images and adjust data, it has become easier for people to ‘plagiarize’. In the scientific publishing domain, until recently, unethical submissions were only identified serendipitously, and this was rare, but there now are several tools to aid publication stakeholders in the automated, thorough and ‘exhaustive’ monitoring3,4 that work well, and have been intercepting and stopping publication trigger investigations leading to retraction in record numbers.5,6 An example of this projection is given in Figure 1. In this tome are presented a snapshot of the plagiarism detection tools and databases7 available to publishers, editors and reviewers. Unfortunately, one of the main limitations of these plagiarism detection software tools is the target databases against which they compare the query text. None of these systems are completely ‘exhaustive’ because the web is a very large place, and although there are a large number of full text publications that are available, they are still only a fraction of the number of scientific, specifically, biomedical publications to date.

Figure 1.

In 2008 there were 4.1 new highly similar pairs of manuscripts per 1,000 published papers in Medline and deposited in the Déjà vu database. This is a major decline that has taken place in the last 2 years. One could speculate on a number of reasons, including fear of detection by would-be perpetrators, but whatever the cause, the problem is getting better but it is still significant in size.

Software/services to detect plagiarism

How it works

software vs. service. Briefly, there are several effective algorithms for the comparison of text which can quickly and accurately compare a submitted document to a large library of published documents, be they peer-reviewed journal publications or web content. These algorithms compare significant keywords (including synonyms, acronyms, lexical variants), statistically improbably phrases (including paraphrased content), and/or align sentences to compute a measure of similarity and then provide those results to the user, including control over thresholds that trigger users to inspect ‘suspiciously similar’ text. Then, these sections of similar text in both the query and that found by the search algorithms are usually displayed as a list or side-by-side to the user to make the final judgment as to acceptability.

Selecting a plagiarism detection service

There are many things to be considered before selecting a plagiarism (or document similarity) detection service. These include, compatibility with ones document management system, completeness (what database do they compare a query to), security, and of course cost. More such considerations are provided in Table 1. Although there are many that offer a plagiarism detection service, and they all claim that have certain advantages over the competition, there has been no head to head competitive analysis by an independent entity to determine the relative performance of each. In Table 2 is a sampling of the available companies and organizations. However, as representative examples of certain types of services/organizations, three will be discussed in more detail – CrossCheck, IThenitcate and eTBLAST – a membership-based plagiarism service for the publication industry, the leading commercial plagiarism detection service for the publication industry, and a free service, respectively.

Table 1.

Considerations when selecting a plagiarism detection system

| Databases searched, completeness, appropriateness |

| Which databases are searched and are they appropriate for my needs? |

| What is my search missing? |

| How often are the search databases updated? |

| Sensitivity and specificity of search algorithm |

| How well does the similarity search work? Or is that known or proprietary? |

| What is the false positive and false negative rate? What is this for my typical queries? |

| How do I handle a false positive? Are there so many that sorting though them is exhausting? |

| Compatibility with journal manuscript submission system |

| How do I automate the checking process? |

| Is there an API available that is compatible with my system? |

| Security |

| How is my data transmitted to and from the service? |

| How long does my query stay in the system? |

| User interface |

| When the results come back, are they presented in a meaningfully and easily assimilated way? |

| Control over threshold and other parameter settings |

| Can I control the settings to minimize false positives and false negatives? |

| Can I give priority to certain manuscript sections (abstract, results, introduction, methods) where different levels of similarity may be tolerated? |

| Ease of use |

| How easy is it to get started? |

| Can I do a test run? |

| Is the automation really working well? |

| Is this helping me? Is it worth it? |

| Cost and contract terms |

| What is the cost? How is the cost computed, unlimited use, or other? |

| Do I have a annual fee? |

| What about free services? |

| Stability, history and reputation of the supplier |

| How long has the company or service been in business? |

| Can they provide a customer reference list? |

| Use and persistence of your query data |

| What happens to my query after I submit it? |

| Is my query deleted or become a permanent part of the search provider’s database? |

| Who owns the results? |

Table 2.

Sampling of free and paid plagiarism detection services

| Company/organization | Product | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| CrossRef.org | Crosscheck (powered by iThenticate) | Annual membership plus a per document fee |

| eTBLAST.org | eTBLAST, déjà vu | Free |

| iParadigms | iTheniticate | Various, per document fee |

| Applied Linguistics | Grarmmarly | Membership fee (although advertized as free |

| Plagiarism-Checkers | CheckForPlagiarism.net | Annual subscription fee |

| Indigo Stream Technologies | Copyscape | Free searches against web, Premium service has a fee per submission |

CrossCheck

CrossCheck is the service provided by the not-for-profit membership based organization, CrossRef, who originally developed the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) which is a reference linking service that provides persistence and linkage for citations. This organization has become a reseller of the iParadigm’s tool, IThenticate, offering it though a membership plus a fee per use financial model. This organization, experienced and knowledgeable of the publication industry, did not develop their own system, but does offer a alternative cost model for the user for the IThenticate services.

IThenticate

IThenticate is a service offered by IParadigms, the same company that has produced the very successful Turnitin plagiarism detection software for use by teachers and professors. The IThenticate product (presumably) has the same proprietary similarity and search engine as Turnitin, but has different (or more) target databases of literature against which they compare a query. Search and detection services offered to publication stakeholders are available, as mentioned above, from CrossCheck, but other purchase models are available directly from iParadigms.

eTBLAST

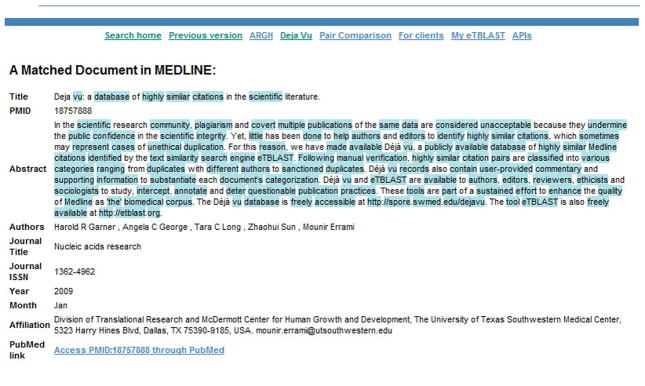

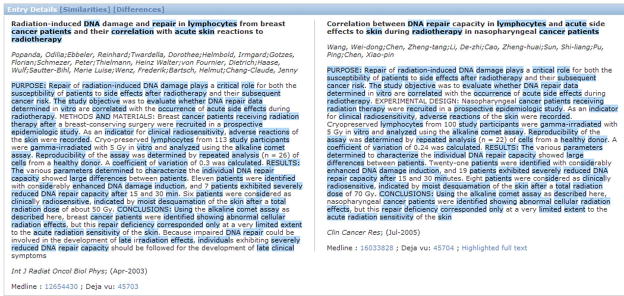

eTBLAST is a free service offered now by the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute and supports several databases, including Medline and arXiv citations and publically available full text. This software service was originally designed as a text analytics software package for reference finding, but it has added benefits offered to the publication stakeholders, including that ability to suggest experts as possible reviews and alternative journals for publication. As illustrative examples of the types of output provided by plagiarism detection services, output from the eTBLAST service are shown in Figures 2 and 3. It is also the engine used to identify highly similar pairs of citations in Medline that have been deposited into the on-line database, Déjà vu, which has become a resource for ethics and sociological studies as well as a teaching-by-example tool.

Figure 2.

Sample output from eTBLAST. In this example, an abstract was retrieved from Medline for a paper that was previously published and submitted to eTBLAST. That abstract had 180 total words, 96 of which were keywords, and it took 16 seconds to 18,941,414 other similar citations in Medline. This example was used to illustrate the output from this engine, which provides a list of citations ranked by level of similarity. Because this query was identical to an existing entry in Medline, it ranked first. In addition, eTBLAST delineated it from the rest because the similarity was greater than 56%, a threshold that was calibrated and reported as suspiciously similar.

Figure 3.

Clicking on the link of the highest ranked entry in the output presented in Figure 2 opens up a page where the words that are similar to the query are shaded. This enables the user to quickly determine if further checking of the full text of the manuscript should be done. A link to the original entry in PubMed is provided, and if this paper was a Open Access publication, as it is, the full text for the paper is available to compare to the query. Please note that across the top are a series of other links, and in particular, the Pair Comparison link provides the ability for a user to put in text from two suspiciously similar sources and then view a comparison, demarked as was done in this figure.

On a final note when selecting a plagiarism detector, there are some features or limitations that potential users may want to consider. Some examples include, when using eTBLAST, it has the advantages of being free, but it is a service provided by a university and although care has been taken to make sure user data is as secure as possible including the destruction of user queries after the analysis is complete, the user assumes full responsibility for its use. On the other hand, the model for Turnitin (and presumably, IThenticate, although it is not clear in their documentation) is to keep all queries and add them to their database, so even submissions rejected for reasons other than plagiarism are still kept, and may show up in future queries. There have been lawsuits over this filed on copyright infringement grounds.

Comparing pairs of documents, regardless of the original method used to ‘detect’ them

Independent of the method used to identify two documents which may be similar, the comparison of those documents can be done by eye or that comparison can be aided by software. This can greatly speed the process and make the results more accurate and quantitative. There are at least two approaches that can be used by publication stakeholders. The first is the “Pair Comparison” feature of eTBLAST. This simple comparison system is used by pasting in two sets of text into the web (select “Pair Comparison” link at http://etblast.org). A quantitative measure of the similarity and a graphic similar to the presentation in Figure 4 is presented as output. The second approach is to use a feature in Microsoft Office Word 2007 to compare documents. This simple approach is exploited through the “Compare two versions of a document” tab under the “Review” tab. After opening two documents, several panes or used to show the user the overlap between the two documents.

Figure 4.

The déjà vu database of highly similar literature, http://dejavu.vbi.vt.edu/dejavu/, was browsed for entries where one of both papers of a highly similar pair were published in the journal, Clinical Cancer Research. This is in entry 23513 in the Déjà vu database. The later highly similar paper was discovered by search similarity and after investigation was retracted (see http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/15/10/3642).

The last word – cleaning up the corpus

The business model of the commercial and not-for-profit companies is to provide plagiarism detection services, and stay away from identifying existing highly similar or plagiarized documents within the scientific corpus. There have been some attempts to identify such documents; however, it is clear that there remain many unidentified documents that may have ethical issues. An even bigger issue is that those documents continue to be unwittingly used by professionals to make scientific, even clinical decisions. Even once questionable documents have been identified, judged and retracted, that retraction notice may never propagate back to the indexing and search services (MedLine and PubMed) that we all frequently use, so we continue to use ‘retracted’ manuscripts, for they are not labeled as such. So, the plagiarism detection services are working to intercept and deter future attempts at plagiarism, but what are we to do with all the plagiarized material that has been accumulating over time?

Webs References

http://etblast.org and http://dejavu.vbi.vt.edu/dejavu/

http://www.crossref.org/crosscheck.html

http://www.checkforplagiarism.net/

http://www.turnitin.com/static/index.html

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Notice

It should be noted that the author of this manuscript is the developer of the eTBLAST and Déjà vu service and database. The figures and computations in this manuscript were obtained from these services as examples of the basic functionality, for it was not possible to find example figures from the other commercial services that were not copyrighted.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Citation References

- 1.Budinger TF, Budinger MD. Ethics of emerging technologies, scientific facts and moral challenges. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, Dicuccio M, Federhen S, Feolo M, Geer LY, Helmberg W, Kapustin Y, Landsman D, Lipman DJ, Lu Z, Madden TL, Madej T, Maglott DR, Marchler-Bauer A, Miller V, Mizrachi I, Ostell J, Panchenko A, Pruitt KD, Schuler GD, Sequeira E, Sherry ST, Shumway M, Sirotkin K, Slotta D, Souvorov A, Starchenko G, Tatusova TA, Wagner L, Wang Y, John Wilbur W, Yaschenko E, Ye J. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 Jan;38(Database issue):D5–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp967. Epub 2009 Nov 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis J, Ossowski S, Hicks J, Errami M, Garner HR. Text Similarity: an alternative way to search MEDLINE. Bioinformatics. 2006 Sep 15;22(18):2298–304. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Errami M, Wren JD, Hicks JM, Garner HR. eTBLAST: A web server to identify expert reviewers, appropriate journals and similar publications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007 Jul;35(Web Server issue):W12–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Errami M, Garner HR. A tale of two citations. Nature. 2008 Jan 24;452(7177):397–9. doi: 10.1038/451397a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long TC, Errami E, George AC, Sun Z, Garner HR. Scientific Integrity: Responding to Possible Plagiarism. Science. 2009 March 6;323:1293–1294. doi: 10.1126/science.1167408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Errami M, Sun Z, Long TC, George AC, Garner HR. Déjà vu: a Database of Duplicate Citations in the Scientific Literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 Jan;37(Database issue):D921–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]