Abstract

Dyadobacter fermentans (Chelius and Triplett, 2000) is the type species of the genus Dyadobacter. It is of phylogenetic interest because of its location in the Cytophagaceae, a very diverse family within the order ‘Sphingobacteriales’. D. fermentans has a mainly respiratory metabolism, stains Gram-negative, is non-motile and oxidase and catalase positive. It is characterized by the production of cell filaments in aging cultures, a flexirubin-like pigment and its ability to ferment glucose, which is almost unique in the aerobically living members of this taxonomically difficult family. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence, and its annotation. This is the first complete genome sequence of the sphingobacterial genus Dyadobacter, and this 6,967,790 bp long single replicon genome with its 5804 protein-coding and 50 RNA genes is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: mesophile, free-living, non-pathogenic, aerobic, chains of rods, Cytophagaceae

Introduction

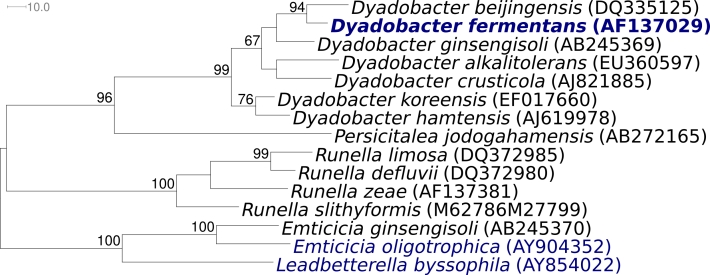

Strain NS114T (= DSM 18053 = ATCC 700827 = CIP 107007) is the type strain of Dyadobacter fermentans, which is the type species of the genus Dyadobacter. D. fermentans was described by Chelius and Triplett in 2000 [1] as mainly aerobic, but also able to grow by fermentation of glucose, Gram negative and nonmotile. The organism is of significant interest for its position in the tree of life, because the genus Dyadobacter (currently seven species, Figure 1) is rather isolated within the family Cytophagaceae [6], as it has less than 88% similarity of the 16S rRNA gene sequence to any other bacteria with standing in nomenclature, with Persicitalea and Runella as closest neighboring genera. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for D. fermentans, strain NS114T (Table 1), together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of D. fermentans strain NS114T, all type strains of the genus Dyadobacter and the most closely related Cytophagaceae type strains, inferred from 1,378 aligned characters [2,3] of the 16S rRNA sequence under the maximum parsimony criterion [4]. The tree was rooted with Emticicia and Leadbetterella, members of the family Cytophagaceae. The branches are scaled in terms of the minimal number of substitutions across all sites. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates if larger than 60%. Strains with a genome sequencing project registered in GOLD [5] are printed in blue; published genomes in bold.

Table 1. Classification and general features of D. fermentans NS114T based on the MIGS recommendations [7].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [6] | |

| Phylum ’Bacteroidetes’ | TAS [6] | ||

| Class ’Sphingobacteria’ | TAS [6] | ||

| Order ’Sphingobacteriales’ | TAS [6] | ||

| Family Cytophagaceae | TAS [8] | ||

| Genus Dyadobacter | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Dyadobacter fermentans | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain NS114 | |||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | rods in pairs or chains | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | nonmotile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | mesophilic | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | not reported | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | tolerates up to 15g NaCl/L | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | essentially aerobic | |

| Carbon source | carbohydrates such as sugars, glucose and sucrose, sugar alcohols and carbonic acids but no polymers such as starch, cellulose or gelatin | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | glucose and sucrose by fermentation aerobically, no acid production from glucose detectable | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | endophytic in stems of maize plants | TAS [1] TAS [12] TAS [9] |

| cysts of nematode Heterodera glycines | |||

| contaminated soil | |||

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | TAS [1] |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [10] | |

| Isolation | surface sterilized stems of maize plants grown in sterile soil without nitrogen fertilizer under green house conditions | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Madison-Wisconsin; USA | NAS |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 | Latitude, Longitude | 43.1, 89.4 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [11]. If the evidence code is IDA the property was directly observed for a live isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Classification and features

Strain NS114T was isolated in a study on the endophytic community of maize plants, where bacteria were isolated from plants which had been grown using surface sterilized seeds in autoclaved synthetic soil in greenhouses [1]. Plant stems were surface sterilized and crushed prior to plating. The organism was found in stem tissues of plants which were cultivated on a nitrogen-free nutrient solution, but not in the nitrogen-fertilized counterparts. The type strain of Runella zeae (NS12T) was co-isolated from the same material, although no microscopic evidence has been presented to date that members of these species were living within the plant tissue [1].

Members of the species D. fermentans were regularly found in cysts of the soybean nematode Heterodera glycines [12]. D. fermentans was also isolated from contaminated soil as a result of its ability to grow on 7,8-benzoquinoline [9], a nitrogen-containing heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (azaarene) widely distributed in products of incomplete combustion processes, with toxic and cancerogenic effects. Two isolates from a lime stone cavern in Arizona share significant 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity of 98% (DQ207364 and DQ207362). Only a few closely related phylotypes from environmental samples and global surveys are recorded to be highly related to D. fermentans, a fact suggesting that members of this taxon are not very abundant: three clones of uncultured bacteria of a deep sea sediment collected at the Western Tropical Pacific Warm Pool in the Pacific Ocean (AM085468, AM085473 and AM085489) and one of the activated sludge of a membrane bioreactor (EU283373) are recorded (as of May 2009). Intrageneric similarity within the genus Dyadobacter is rather low [13].

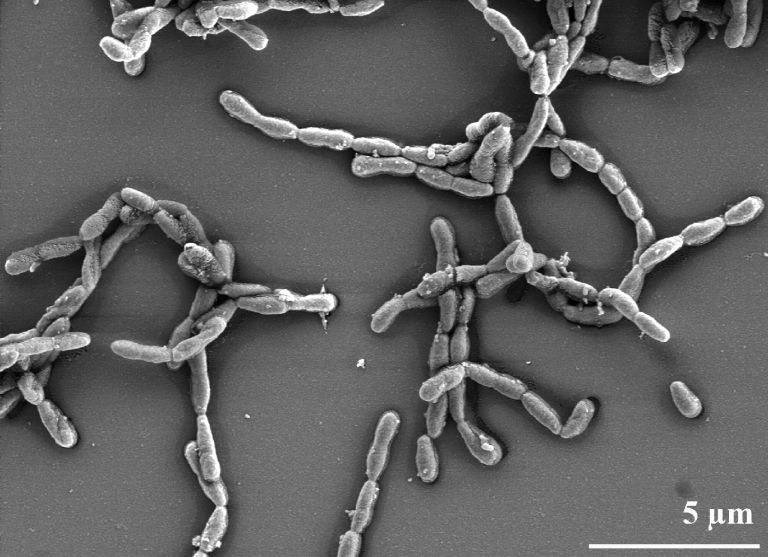

D. fermentans has been recognized by its flexirubin-like yellow pigment and by its growth as flocculent filaments of ovoid rods in old cultures [1]. The rod-shaped cells of strain NS114T occur polarly attached in groups of 2-4 cells during logarithmic growth, cells being frequently arranged at an angle to give V-formations. As the culture ages, irregular filaments or ovoid rods form (Figure 2) which sediment as fluffs in liquid culture [1]. The cells are Gram negative, non-motile and non-sporulating, oxidase and catalase positive. Like many plant associated bacteria, strain NS114T produces copious amounts of slime when grown on nitrogen-limited agar. The organism grows aerobically, however it is also reported to be able to ferment glucose and sucrose in the O/F-test in Hugh-Leifson medium [1,13], which according to our own observations might be an experimental artifact due to prolonged incubation. The colony color of strain NS114T is yellow to orange [1,13]. The absorbance maximum of an ethanol extract of the cells is at 450 nm, and the absorbance peak broadens under alkaline conditions, which is a typical feature of flexirubin-like pigments [1]. This pigment was found in all six species of the genus Dyadobacter thus confirming that the presence of the pigment is a property of the genus [14-18].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of D. fermentans NS114T

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of D. fermentans strain NS114T in a 16S rRNA based tree. Analysis of the four 16S rRNA gene sequences in the genome of strain NS114T indicated that three copies are almost identical, and one differs by seven nucleotides from these. The sequences of the three identical 16S rRNA genes differ by two nucleotides from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence generated from DSM 18053 (AF137029). The slight differences between the genome data and the reported 16S rRNA gene sequence are probably the result of sequencing errors in the previously reported sequence data.

The whole cell fatty acid pattern of strain NS114T is dominated by unsaturated, and saturated iso-branched, straight chain unsaturated and large amounts of iso-branched, hydroxylated species. Major components are iso-C15:0-2OH and/or C16:1ω7c (43.5%), C16:1 ω5c (17.5%) and iso-C15:0 (16.8). Considerable amounts of the 3-hydroxylated fatty acids iso-C15:0-3OH, C16:0-3OH and iso-C17:0 -3OH are detected [1]. The quinone composition has not been investigated for strain NS114T. The main component reported for the closely related type strains of D. ginsengisoli and D. alkalitolerans is menaquinone MK-7 [16,18]. Cells of strain NS114T contain spermidine as the major cellular polyamine and putrescine, cadaverine and spermine as minor components. The latter compound was not detected in any of the three other strains studied to date of the family Cytophagaceae, representing Flexibacter flexilis, Microscilla marina, and D. beijingensis [19]. The polar lipid composition has not been investigated in either this strain or other members of the genus Dyadobacter.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [5] and the complete genome sequence in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two genomic Sanger libraries: 8 kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 10.6× Sanger |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Phred/Phrap/Consed |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal, GenePrimp |

| INSDC / Genbank ID | CP001619 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | July 31, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01069 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501416930 | |

| NCBI project ID | 20829 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 18053 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

D. fermentans NS114T, DSM18053, was grown in DSMZ medium 830 (R2A Medium) at 28°C [20]. DNA was isolated from 1-1.5 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with a modified protocol (FT) for cell lysis as described in Wu et al. [21].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of 8 kb and fosmid DNA libraries. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at the JGI website (http://www.jgi.doe.gov). Draft assemblies were based on 86,260 total reads. The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package (http://www.phrap.com) was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment [22-24]. After the shotgun stage, reads were assembled with parallel phrap. Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones [25]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 1,042 additional reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together all libraries provided 10.6x coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [26] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline , followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [27]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [28].

Genome properties

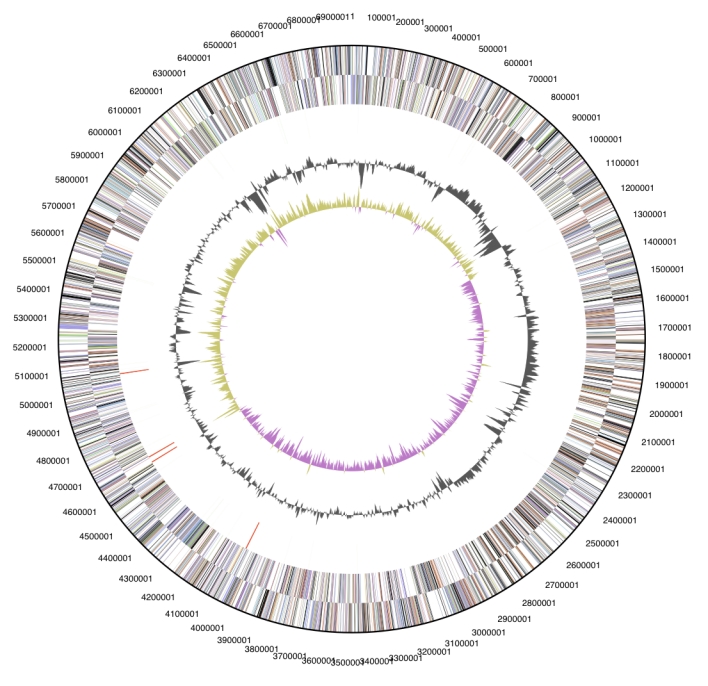

The genome is 6,967,790 bp long and comprises one main circular chromosome with a 51.4% GC content (Table 3, Figure 3). Of the 5,854 genes predicted, 5,804 were protein coding genes, and 50 were RNAs. In addition, 85 pseudogenes were identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (64.7%) were assigned with a putative function while those remaining were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3. The distribution of genes into COG functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 6,967,790 | 100.00% | |

| DNA Coding region (bp) | 6,343,890 | 91.05% | |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 3,591,547 | 51.54% | |

| Number of replicons | 1 | ||

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | ||

| Total genes | 5,854 | 100.00% | |

| RNA genes | 50 | 0.85% | |

| rRNA operons | 4 | ||

| Protein-coding genes | 5,804 | 99.15% | |

| Pseudo genes | 85 | 1.45% | |

| Genes with function prediction | 3,790 | 64.74% | |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 1,250 | 21.35% | |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,702 | 63.24% | |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 3,853 | 65.82% | |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,760 | 30.06% | |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,239 | 21.17% | |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | ||

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | % of total | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 171 | 2.9 | Translation |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 392 | 6.8 | Transcription |

| L | 157 | 2.7 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 23 | 0.4 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 111 | 1.9 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 343 | 5.9 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 345 | 5.9 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 13 | 0.2 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 56 | 1.0 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 110 | 1.9 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 179 | 3.1 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 335 | 5.8 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 247 | 4.4 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 75 | 1.3 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 190 | 3.3 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 143 | 2.5 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 295 | 5.1 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 102 | 1.8 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 540 | 9.3 | General function prediction only |

| S | 345 | 5.9 | Function unknown |

| - | 2102 | 36.2 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Susanne Schneider (DSMZ) for DNA extraction and quality analysis. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1.

References

- 1.Chelius MK, Triplett EW. Dyadobacter fermentans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel Gram-negative bacterium isolated from surface-sterilized Zea mays stems. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2000; 50:751-758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4.0 b10. 2002, Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrity GM, Lilburn TG, Cole JR, Harrison SH, Euzéby J, Tindall BJ. Taxonomic Outline of the Bacteria and Archaea Release 7.7 March 6, 2007. Michigan State University Board of Trustees. DOI: 10.1601/TOBA7.7. http://www.taxonomicoutline.org/index.php/toba

- 7.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. Towards a richer description of our complete collection of genomes and metagenomes: the “Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence” (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skerman VBD, McGrowan V, Sneath PHA, eds. Approved list of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30: 225-420 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willumsen PA, Johansen JE, Karlson U, Hansen BM. Isolation and taxonomic affiliation of N-heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-transforming bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2005; 67:420-428 10.1007/s00253-004-1799-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous. Biological Agents: Technical rules for biological agents www.baua.de

- 11.Botstein D, Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nour SM, Lawrence JR, Zhu H, Swerhone GD, Welsh M, Welacky TW, Topp E. Bacteria associated with cysts of the soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines). Appl Environ Microbiol 2003; 69:607-615 10.1128/AEM.69.1.607-615.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaturvedi P, Reddy GSN, Shivaji S. Dyadobacter hamtensis sp. nov., from Hamta glacier, located in the Himalayas, India. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:2113-2117 10.1099/ijs.0.63806-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong Z, Guo X, Zhang X, Qiu F, Sun L, Gong H, Zhang F. Dyadobacter beijingensis sp. nov., isolated from the rhizosphere of turf grasses in China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:862-865 10.1099/ijs.0.64754-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy GSN, Garcia-Pichel F. Dyadobacter crusticola sp. nov., from biological soil crusts in the Colorado Plateau, USA, and an emended description of the genus Dyadobacter Chelius and Triplett 2000. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:1295-1299 10.1099/ijs.0.63498-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu QM, Im WT, Lee M, Yang DC, Lee ST. Dyadobacter ginsengisoli sp. nov., isolated from soil of a ginseng field. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1939-1944 10.1099/ijs.0.64322-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baik KS, Kim MS, Kim EM, Kim HR, Seong CN. Dyadobacter koreensis sp. nov., isolated from fresh water. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:1227-1231 10.1099/ijs.0.64902-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Y, Dai J, Zhang L, Mo Z, Wang Y, Li Y, Ji S, Fang C, Zheng C. Dyadobacter alkalitolerans sp. nov., isolated from desert sand. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:60-64 10.1099/ijs.0.001404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosoya R, Hamana K. Distribution of two triamines, spermidine and homospermidine, and an aromatic amine, 2-phenylethylamine, within the phylum Bacteroidetes. J Gen Appl Microbiol 2004; 50:255-260 10.2323/jgam.50.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 21.Wu M, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova N, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; (Submitted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res 1998; 8:175-185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res 1998; 8:186-194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res 1998; 8:195-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han CS, Chain P. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher. In: Proceeding of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics & computational biology. Hamid R Arabnia & Homayoun Valafar (eds), CSREA Press. June 26-29, 2006:141-146 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anonymous. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. Oak Ridge National Laboratory and University of Tennessee 2009 http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal

- 27.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. (Submitted). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. Expert Review of Functional Annotations for Microbial Genomes. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]