Abstract

Halomicrobium mukohataei (Ihara et al. 1997) Oren et al. 2002 is the type species of the genus Halomicrobium. It is of phylogenetic interest because of its isolated location within the large euryarchaeal family Halobacteriaceae. H. mukohataei is an extreme halophile that grows essentially aerobically, but can also grow anaerobically under a change of morphology and with nitrate as electron acceptor. The strain, whose genome is described in this report, is a free-living, motile, Gram-negative euryarchaeon, originally isolated from Salinas Grandes in Jujuy, Andes highlands, Argentina. Its genome contains three genes for the 16S rRNA that differ from each other by up to 9%. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. This is the first completed genome sequence from the poorly populated genus Halomicrobium, and the 3,332,349 bp long genome (chromosome and one plasmid) with its 3416 protein-coding and 56 RNA genes is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: extreme halophile, mesophile, free-living, motile, non-pathogenic, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped, Halobacteriaceae

Introduction

Strain arg-2T (= DSM 12286 = ATCC 700874 = JCM 9738) is the type strain of the species Halomicrobium mukohataei, and represents the type species of the genus Halomicrobium [1]. H. mukohataei was initially described as Haloarcula mukohataei (basonym) by Ihara et al. 1997 [2]. H. mukohataei is a motile, extremely halophilic euryarchaeon. The organism is of significant interest for its isolated position in the tree of life within the genus Halomicrobium in the family Halobacteriaceae. H. katesii [3] is currently the only other cultivated member of the genus Halomicrobium. Only two uncultivated archaeal clones related to the genus (>98% sequence identity) have been reported from diversity screenings: clone XCDLW-A62 from saline lakes on the Tibetan Plateau (FJ155620), and clone SA93 from an athalassohaline environment in the Tirez Lagoon in Spain (EU722674). No phylotypes from environmental samples or genomic surveys could be directly linked to H. mukohataei. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for H. mukohataei arg-2T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

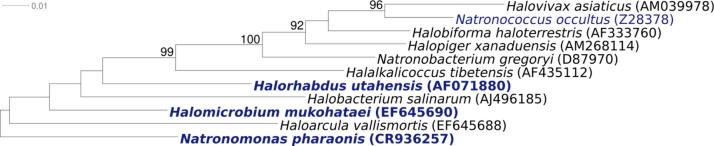

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of H. mukohataei strain arg-2T in a 16S rRNA based tree. Two of the three 16S rRNA gene copies in the H. mukohataei arg-2T genome are identical, but differ by 131 nucleotides (9%) from the third copy (23S rRNA gene sequences differ by only 1-1.7%, this study). Studies on the ribosomes indicate that operons which differ significantly in their sequence are expressed under different environmental conditions [9], as has also been reported for members of the genus Haloarcula [10]. The symbols rrnA and rrnB used in Figure 1 for these distinct rRNA copies in Haloarcula and Halomicrobium are in accordance with the designations used by Cui et al. 2009 [9]. The two identical 16S rRNA genes differ in one nucleotide from the previously reported reference sequence of strain arg-2T derived from JCM 9738 (EF645690).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of H. mukohataei arg-2T, all type strains of the genera Halomicrobium and Haloarcula and type strains of other selected members of the family Halobacteriaceae, inferred from 1,430 aligned characters [4,5] of the 16S rRNA gene using the neighbor-joining algorithm and K2P distances [6]. The tree was rooted with Natronomonas pharaonis, the deepest branching member of the family Halobacteriaceae. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates if larger than 60%. Strains with a genome sequencing project registered in GOLD [7] are printed in blue; published genomes in bold, e.g. the GEBA genome from Halorhabdus utahensis [8].

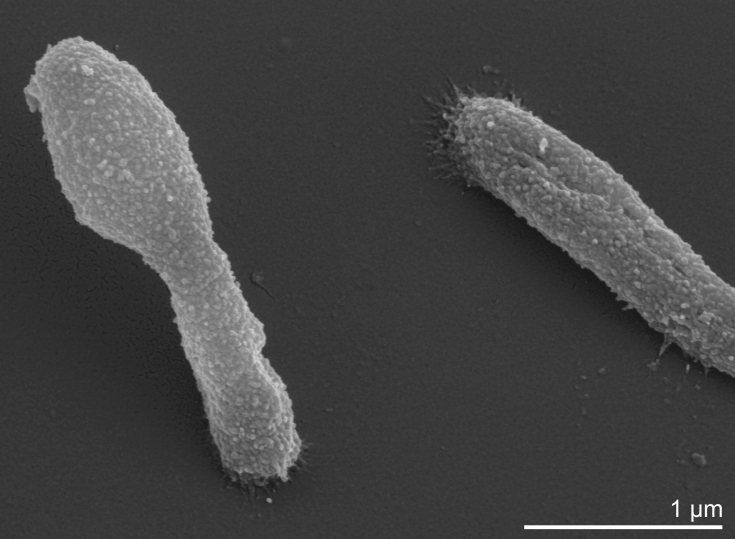

H. mukohataei is rod shaped (Table 1), but may produce pleomorphic cells in the stationary phase [1] (Figure 2). There are conflicting reports concerning the type of flagellation, which may be either polar or in tufts or peritrichous [1]. Gas vacuoles have not been reported and resting stages such as spores are not produced. Cells are Gram-negative, although peptidoglycan is probably absent [1]. Strain arg-2T grows under aerobic conditions, but may also grow anaerobically in the presence of nitrate [1]. Arginine does no support anaerobic growth. Acids are produced from glucose, galactose, mannose, ribose, sucrose, maltose and glycerol [1]. Glucose, galactose, sucrose, maltose and glycerol support growth as single carbon and energy sources. Starch is hydrolyzed [1], however, gelatin, casein and Tween 80 are not hydrolyzed. Requires at least 2M NaCl to maintain cell shape, with optimal growth occurring at 3.0-3.5 M NaCl. Catalase and oxidase positive. Optimal growth temperature is 40-45°C [1].

Table 1. Classification and general features of H. mukohataei arg-2T in accordance to the MIGS recommendations [11].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Archaea | TAS [12] | |

| Phylum Euryarchaeota | TAS [13] | ||

| Class Halobacteria | TAS [14] | ||

| Order Halobacteriales | TAS [15] | ||

| Family Halobacteriaceae | TAS [16] | ||

| Genus Halomicrobium | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Halomicrobium mukohataei | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain arg-2 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | short rod with variable cell length; above 45°C spherical morphology | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | motile, multiple peritrichous or tufts of flagella | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | NAS | |

| Temperature range | mesophile, <52°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 40-45°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | extremely halophilic; requires 2.5-4.5 M NaCl, optimum 3-3.5 M NaCl | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | essentially aerobic; grows anaerobically with nitrate as electron acceptor | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | glucose, galactose, sucrose, maltose, glycerol | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | glucose, galactose, sucrose, maltose, glycerol | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | soils of salt flats | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | TAS [17] |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [17] | |

| Isolation | soils of salt flats in Salinas Grandes from Andes highlands | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Jujuy, Argentina | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1991 | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 | Latitude, Longitude | -22.66, -66.23 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Sea level | NAS |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [18]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a living isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of H. mukohataei arg-2T

Chemotaxonomy

The quinone composition of H. mukohataei arg-2T has not been investigated, but based on reports from other members of the family Halobacteriaceae menaquinones with eight isoprenoid units are likely to be present. Typically both MK-8 and MK-8 (VIII-H2) may be predicted. The lipids are based on diphytanyl ether lipids. The major phospholipids are the diphytanyl ether analogues of phosphatidylglycerol and methyl-phosphatidylglycerophosphate (typical of all members of the family Halobacteriaceae), the diether analogue of phosphatidylglycerol sulfate is present [1]. Glycolipids have been reported, one of which has a molecular weight typical of a sulfate diglycosyl diphytanyl ether, the structure of which has not been determined [1]. A diglycosyl diphytanyl ether lipid is also present. The pigments responsible for the red color of the cells have not been recorded, but it may be predicted that they are carotenoids, probably bacterioruberins. Outer cell layers are probably proteinaceous. The presence of peptidoglycan has not been investigated, but is generally absent from members of this family Halobacteriaceae.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [7] and the complete genome sequence in GenBank Sequencing, finishing and annotation was performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic libraries: two Sanger libraries - 8 kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos and one 454 pyrosequencing standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 GS FLX |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 13.4x Sanger; 31× pyrosequencing |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 1.1.02.15, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001688 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | September 9, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01100 | |

| NCBI project ID | 27945 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501416928 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 12286 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

H. mukohataei arg-2T, DSM 12286, was grown in DSMZ medium 372 (Halobacterial Medium) [19] at 35°C. DNA was isolated from 1-1.5 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with a modified protocol for cell lysis, (procedure L), according to Wu et al. [20].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at the JGI website (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/). 454 Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 3,703 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using the parallel phrap assembler (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones [21]. A total of 39 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together, the combination of the Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms provided 44.4× coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 48,917 Sanger reads and 443,713 pyrosequencing reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [22] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline (http://geneprimp.jgi-psf.org/) [23]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review platform (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/er) [24].

Genome properties

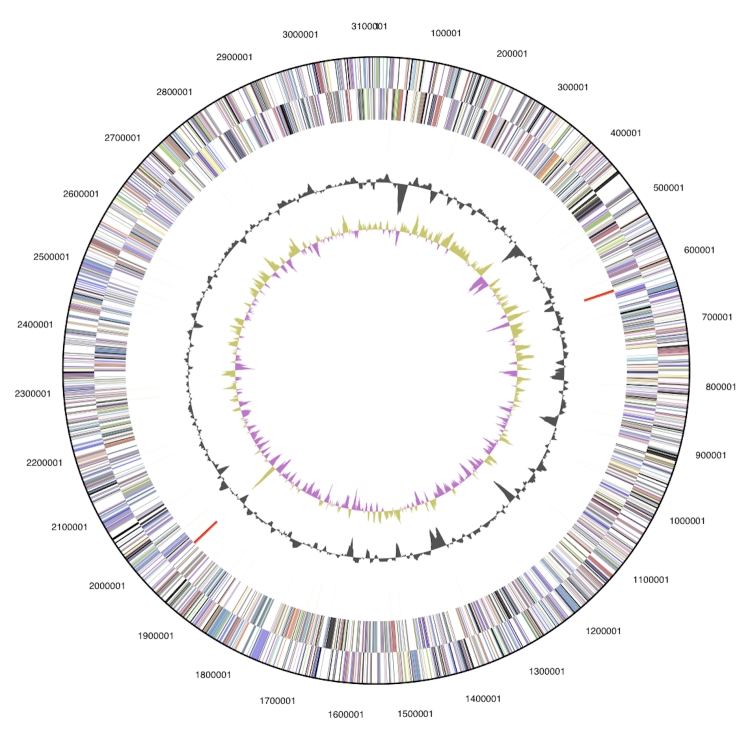

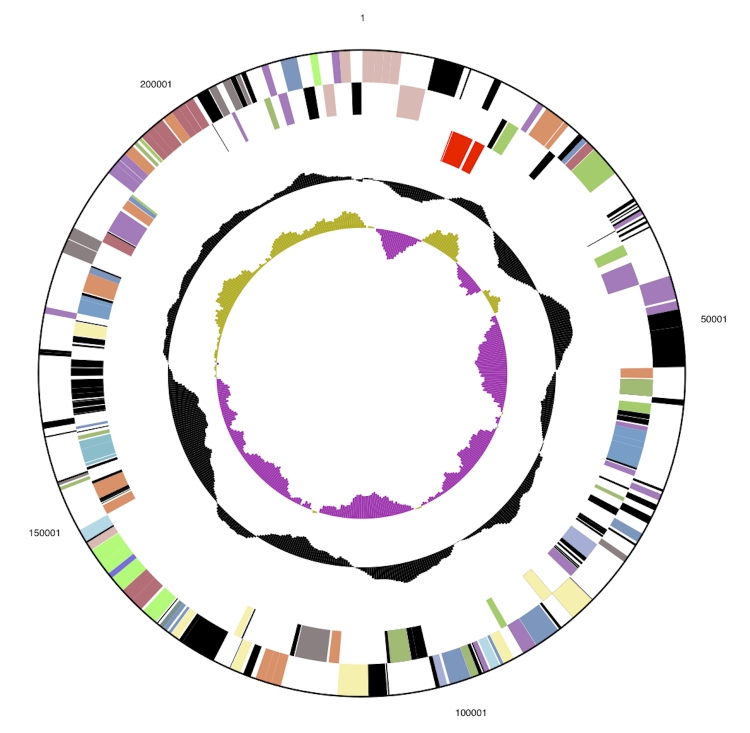

The genome is 3,332,349 bp long and comprises one main circular chromosome of 3.11 Mbp and one 219 kbp megaplasmid with a 65.5% GC content (Table 3, Figure 3a and Figure 3b). Of the 3,472 genes predicted, 3,416 were protein coding genes, and 56 RNAs. In addition, 66 pseudogenes were identified. The majority of the genes (59.4%) were assigned with a putative function while those remaining were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,332,349 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,927,602 | 87.85% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,183,712 | 65.53% |

| Number of replicons | 2 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 1 | |

| Total genes | 3,472 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 56 | 1.61% |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 3,416 | 98.30% |

| Pseudo genes | 66 | 1.90% |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,081 | 59.88% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 610 | 17.55% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,135 | 61.44% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2,079 | 59.83% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 465 | 13.38% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 874 | 25.15% |

| CRISPR repeats | 2 |

Figure 3a.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Figure 3b.

5.5x enlarged (vs. chromosome) graphical circular map of the megaplasmid.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | % age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 157 | 4.6 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 124 | 3.6 | Transcription |

| L | 146 | 4.3 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 3 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 29 | 0.8 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 30 | 0.8 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 129 | 3.7 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 85 | 2.5 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 47 | 1.3 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 26 | 0.7 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 98 | 2.8 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 142 | 4.1 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 124 | 3.6 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 205 | 6.0 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 66 | 1.9 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 125 | 3.6 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 65 | 1.9 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 137 | 4.0 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 38 | 1.1 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 374 | 10.9 | General function prediction only |

| S | 213 | 8.2 | Function unknown |

| - | 1281 | 37.5 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Regine Fähnrich and Helga Pomrenke (both at DSMZ) in cultivation of the strain. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396 as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1.

References

- 1.Oren A, Elevi R, Watanabe S, Ihara K, Corcelli A. Halomicrobium mukohataei, gen. nov., comb. nov., an emended description of Halomicrobium mukohataei. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1831-1835 10.1099/ijs.0.02156-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ihara K, Watanabe S, Tamura T. Haloarcula argentinensis, gen. nov. and Haloarcula mukohataei sp. nov., two new extremely halophilic archaea collected in Argentina. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:73-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kharroub K, Lizama C, Aguilera M, Boulahrouf A, Campos V, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Monteoliva-Sánchez M. Halomicrobium katesii sp. nov., an extremely halophilic archaeon. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:2354-2358 10.1099/ijs.0.65662-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4.0 b10. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liolios K, Mavrommatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson I, Tindall BJ, Pomrenke H, Göker M, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Chen F, Tice H, et al. Complete genome of Halorhabdus utahensis type strain (AX-2T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:218-225 10.4056/sigs.31864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui HL, Zhou PJ, Oren A, Liu SJ. Intraspecific polymorphism of 16S rRNA genes in two halophilic archaeal genera, Haloarcula and Halomicrobium. Extremophiles 2009; 13:31-37 10.1007/s00792-008-0194-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-López A, Benlloch S, Bonfá M, Rodríguez-Valera F, Mira A. Intragenomic 16S rDNA Divergence in Haloarcula marismortui is an adaptation to different temperatures. J Mol Evol 2007; 65:687-696 10.1007/s00239-007-9047-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. Towards a richer description of our complete collection of genomes and metagenomes: the “Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence” (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrity GM, Holt JG. Phylum AII. Euryarchaeota phy. nov. In: Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. 1. 2nd ed. Edited by: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW. Springer, New York; 2001; pp 211-355. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant WD, Kamekura M, McGenity TJ, Ventosa A. Class III. Halobacteria class. nov. In: Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd edn, vol. 1, p. 294. Edited by DR Boone, RW Castenholz & GM Garrity. New York: Springer. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant WD, Larsen H. Extremely halophilic archaebacteria, order Halobactenales ord. nov., p. 2216-33. In: Staley JT, Bryant MP, Pfennig N & Holt JG (eds), Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 3. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons NE. Family V. Halobacteriaceae fam. nov. In: Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, 8th edn, pp. 269–273. Buchanan RE & Gibbons NE(eds). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anonymous. Biological Agents: Technical rules for biological agents www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 18.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/ media_list.php

- 20.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova N, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter JC, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Galvina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anonymous. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. Oak Ridge National Laboratory and University of Tennessee 2009 http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal/

- 23.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. (Submitted). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Kyrpides NC. Expert IMG ER: A system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]