Abstract

Gordonia bronchialis Tsukamura 1971 is the type species of the genus. G. bronchialis is a human-pathogenic organism that has been isolated from a large variety of human tissues. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. This is the first completed genome sequence of the family Gordoniaceae. The 5,290,012 bp long genome with its 4,944 protein-coding and 55 RNA genes is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: Obligate aerobic, human-pathogenic, endocarditis, Gram-positive, non-motile, Gordoniaceae

Introduction

Strain 3410T (= DSM 43247 = ATCC 25592 = JCM 3198) is the type strain of the species Gordonia bronchialis, which is the type species of the genus. The genus Gordonia (formerly Gordona) was originally proposed by Tsukamura in 1971 [1]. The generic name Gordona has been chosen to honor Ruth E. Gordon, who studied extensively ‘Mycobacterium’ rhodochrous (included later as a member of Gordona) [1]. In 1977, it was subsumed into the genus Rhodococcus [2], but revived again in 1988 by Stackebrandt et al. [3]. At the time of writing, the genus contained 28 validly published species [4]. The genus Gordonia is of great interest for its bioremediation potential [5]. Some species of the genus have been used for the decontamination of polluted soils and water [6,7]. Other species were isolated from industrial waste water [8], activated sludge foam [9], automobile tire [10], mangrove rhizosphere [11], tar-contaminated oil [12], soil [13] and an oil-producing well [7]. Further industrial interest in Gordonia species stems from their use as a source of novel enzymes [14,15]. There are, however, quite a number of Gordonia species that are associated with human and animal diseases [16], among them G. bronchialis. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for G. bronchalis 3410T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

Strain 3410T was isolated from the sputum of a patient with pulmonary disease (probably in Japan) [1]. Further clinical strains in Japan have been isolated from pleural fluid, tumor in the eyelid, granuloma, leukorrhea, skin tissue and pus [17]. In other cases, G. bronchialis caused bacteremia in a patient with a sequestrated lung [18] and a recurrent breast abscess in an immunocompetent patient [19]. Finally, G. bronchialis was isolated from sternal wound infections after coronary artery bypass surgery [20]. G. bronchialis shares 95.8-98.7% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with the other type strains of the genus Gordonia, and 95.3-96.4% with the type strains of the neighboring genus Williamsia.

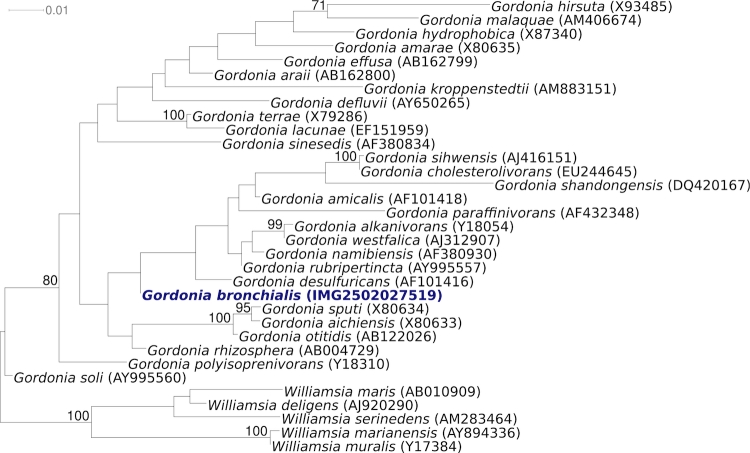

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of for G. bronchialis 3410T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the two 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome of G. bronchialis 3410T, differ from each other by one nucleotide, and differ by up to 5 nucleotides from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence from DSM 43247 (X79287). These discrepancies are most likely due to sequencing errors in the latter sequence.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of G. bronchialis 3410T relative to the other type strains within the genus Gordonia. The tree was inferred from 1,446 aligned characters [21,22] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [23] and rooted with the type strains of the neighboring genus Williamsia. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [24] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold.

In a very comprehensive study, Tsukamura analyzed a set of 100 quite diverse characters for 41 G. bronchialis strains isolated from sputum of patients with pulmonary disease, including the type strain [1]. Unfortunately, this study does not present the characteristics of the type strain 3410T as such. We nevertheless first present these data, as this study gives a good overview of the species itself. In order to summarize the data here, we regard positive reactions in more than 34 strains as positive, and positive reactions in only 13 or less strains as negative. Most characters, however, are either clearly positive (40 or 41 strains) or clearly negative (0 or 1 strains). The detailed methods are reported elsewhere [25,26].

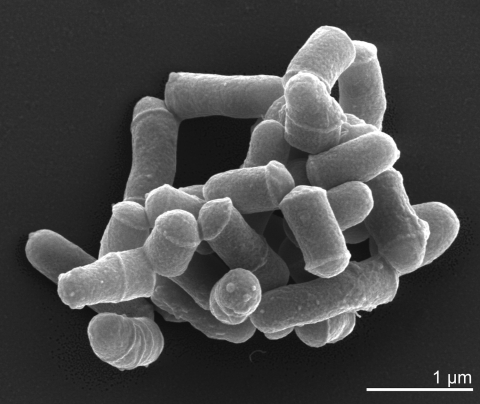

G. bronchialis is Gram-positive (Table 1) and shows slight but not strong acid-fastness. A mycelium is not observed. G. bronchialis strains are non-motile and produce neither conidia nor endospores [1,3]. G. bronchialis is an obligately aerobic chemoorganotroph with an oxidative-type metabolism [3].The cells are rod-shaped and show compact grouping (like a cord) (Figure 2), and provide a rough colonial morphology with pinkish-brown colony pigmentation [1]. Photochromogenicity was not observed. G. bronchialis grows quite rapidly [1], with visible colonies appearing within 1-3 days [1,36]. G. bronchialis is positive for catalase and nitrate reduction, but arylsulphatase (3 days and 2 weeks), salicylate and PAS degradation was not observed [1]. Growth occurs on 0.2% sodium p-aminosalicylate and 62.5 and 125 µg NH2OH-HCl/ml, but not with 250 or 500 µg. G. bronchialis is tolerant to both 0.1 and 0.2% picric acid. G. bronchialis grows at 28°C and 37°C, but not at 45°C or 52°C [1]. G. bronchialis is positive for acetamidase, urease, nicotinamidase and pyrazinamidase, but negative for benzamidase, isonicotinamidase, salicylamidase, allanoinase, succinamidase, and malonamidase [1]. G. bronchialis utilizes acetate, succinate, malate, pyruvate, fumarate, glycerol, glucose, mannose, trehalose, inositul, fructose, sucrose, ethanol, propanol, and propylene glycol as a carbon source for growth, but not citrate, benzoate, malonate, galactose, arabinose, xylose, rhamnose, raffinose, mannitol, sorbitol, or various forms of butylene glycol (1,3-; 1,4-; 2,3-) [1]. G. bronchialis utilizes L-glutamate and acetamide as a N-C source, but not L-serine, benzamide, monoethanolamine or trimethylene diamine. Glucosamine is utilized by 18 strains [1]. G. bronchialis utilizes as nitrogen source L-glutamate, L-serine, L-methionine, acetamide, urea, pyrazinamide, isonicotinamide, nicotinamide, succinamide, but not benzamide and nitrite. Nitrate is utilized by 25 strains as nitrogen source [1]. G. bronchialis strains do not produce nicotinic acid. G. bronchialis strains do not grow on TCH medium (10 µg/ml) or on salicylate medium (0.05% and 0.01%) [1].

Table 1. Classification and general features of G. bronchialis 3410T according to the MIGS recommendations [27].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [28] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [29] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [30] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [30] | ||

| Suborder Corynebacterineae | TAS [30,31] | ||

| Family Gordoniaceae | TAS [30] | ||

| Genus Gordonia | TAS [3,30,32] | ||

| Species Gordonia bronchialis | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain 3410 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | positive | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | short rods in compact grouping (cord-like) | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | non-motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | grows at 28°C and 37°C, not at 45°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | probably between 28°C and 37°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | 2.5% | TAS [33] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | obligate aerobe | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | mono- and disaccharides | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | chemoorganotroph | TAS [3] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | human | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | opportunistic pathogen | TAS [1,17-20] |

| Biosafety level | 2 | TAS [34] | |

| Isolation | sputum from human with pulmonary disease in (probably) Japan |

TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | global | TAS [1,17-20] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1971 or before | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 | Latitude, Longitude | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [35]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a live isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of G. bronchialis 3410T

In the following, characteristics of the type strain 3410T are presented: strain 3410T reduces nitrate and hydrolyses urea, but it does not hydrolyze aesculin, allantoin or arbutin [37]. It decomposes (%, w/v) starch (1) and uric acid (0.5), but not hypoxanthine (0.4), tributyrin (0.1), tween 80 (1), tyrosine (0.5) and xanthine (0.4) [37]. It grows on glycerol (1) and sodium fumarate (1) as sole carbon sources (%, w/v), but not on arbutin (1), D-cellobiose (1), N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (0.1), adipic acid (0.1), betaine (0.1), oxalic acid (0.1), propan-1-ol (0.1) [37]. Strain 3410T grows in the presence (% w/v) of oleic acid (0.1) and zinc chloride (0.001) [37].

In an API ZYM test, strain 3410T reacts positively for alkaline phosphatase, butyrate esterase, leucine arylamidase and naphtol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, but not for caprylate esterase, cystine arylamidase, β-glucosidase, myristate lipase, and valine arylamidase [13]. Complementary to the results of Tsukamura [1], strain 3410T utilizes as sole carbon source D(+) cellobiose, D(+) galactose, D(+) mannose, meso-inositol, L(+) rhamnose and sodium succinate, but not D(-)lactose, D(-) ribose, sodium benzoate and sodium citrate [38]. The use of D(+) galactose [38] might contrast above reported results from Tsukamura [1]. L-threonine and L-valinine are used as sole nitrogen source by strain 3410T, but not L-asparagine, L-proline and L-serine [38]. Interestingly, Tsukamura reports that 40 out of 41 strains utilize L-serine as sole nitrogen source [1], and it is not clear if the only negative strain in the Tsukamura study could be the type strain 3410T [1].

In the BiOLOG system, strain 3410T reacts positively for α-cyclodextrin, β-cyclodextrin, dextrin, glycogen, maltose, maltotriose, D -mannose, 3-methyl glucose, palatinose, L-raffinose, salicin, turanose, D-xylose, L-lactic acid, methyl succinate, N-acetyl- L-glutamic acid [12], but not for N-acetylglucosamine, amygdalin, D-arabitol, L-Rhamnose, D-ribose, D-sorbitol, D-trehalose, acetic acid, α-hydroxybutyric acid, β-hydroxybutyric acid, α-ketoglutaric acid, α-ketovaleric acid, L-lactic acid methyester, L-malic acid, propionic acid, succinamic acid, alaninamide, L-alanine and glycerol [12]. Further carbon source utilization results are published elsewhere [8].

Drug susceptibility profiles of 13 G. bronchialis strains from clinical samples have been examined in detail [17], but they are too complex to summarize here. No significant matches with any 16S rRNA sequences from environmental genomic samples and surveys are reported at the NCBI BLAST server (November 2009).

Chemotaxonomy

The cell-wall peptidoglycan is based upon meso-diaminopimelic acid (variation Alγ). The glycan moiety of the peptidoglycan contains N-glycolylmuramic acid. The wall sugars are arabinose and galactose. Mycolic acids are present with a range of ca. 48-66 carbon atoms. The predominant menaquinone is MK-9(H2), with only low amounts of MK-9(H0), MK-8(H2), and MK-7(H2) [3,8,39-41]. Moreover, the cell envelope of G. bronchialis 3410T contains a lipoarabinomannan-like lipoglycan [42]. The same study also observed a second amphiphilic fraction with properties suggesting a phosphatidylinositol mannoside [42]. The cellular fatty acid composition (%) is C16:0 (23), tuberculostearic acid (20), C16:1cis9 (16), C16:1cis7 (11), C18:1 (10), and 10-methyl C17:0 (7). All other fatty acids are at 3% or below [8].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [24] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two Sanger libraries: 8kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos One 454 Pyrosequence standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 GS FLX |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 7.98× Sanger; 23.2× Pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001802 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | October 28, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01134 | |

| NCBI project ID | 29549 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501939625 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 43247 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

G. bronchialis 3410T, DSM 43247, was grown in DSMZ 535 [43] at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 1-1.5 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions with modification st/LALMP for cell lysis according to Wu et al. [44].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found on the JGI website. 454 Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 5,776 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and to adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using the parallel phrap assembler (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher [45] or transposon bombing of bridging clones (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 876 primer walk reactions, 12 transposon bombs, and 1 pcr shatter libraries were necessary to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together all sequence types provided 51.2 × coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 52,329 Sanger and 508,130 pyrosequence reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [46] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [47]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [48].

Genome properties

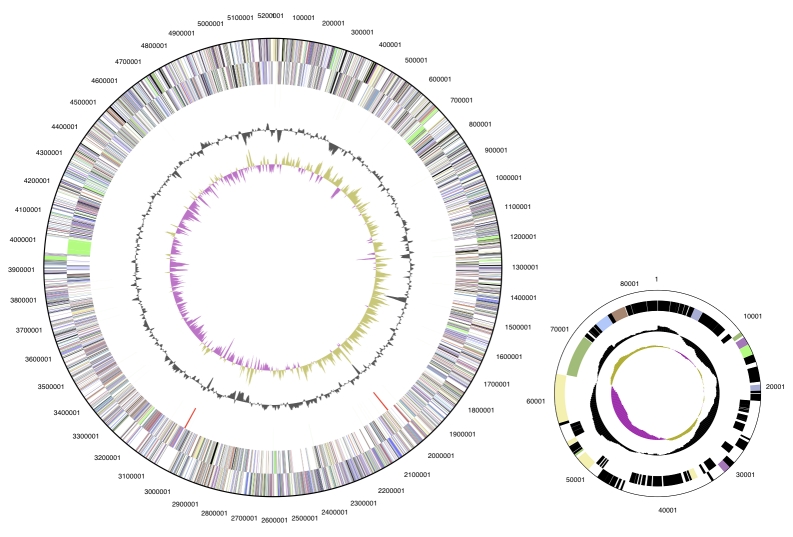

The genome consists of a 5.2 Mbp long chromosome and a 81,410 bp plasmid (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 4,999 genes predicted, 4,944 were protein coding genes, and 55 RNAs; 264 pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (69.1%) were assigned with a putative function while those remaining were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 5,290,012 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 4,897,508 | 92.58% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 3,546,559 | 67.04% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 1 | |

| Total genes | 4,999 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 55 | 1.10% |

| rRNA operons | 2 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 4,944 | 98.90% |

| Pseudo genes | 264 | 5.28% |

| Genes with function prediction | 3,453 | 69,07% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 804 | 16.08% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,335 | 66.71% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 3,508 | 70.17% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,038 | 20.76% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,209 | 24.18% |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome and the plasmid. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 164 | 3.3 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 357 | 7.2 | Transcription |

| L | 238 | 4.8 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 28 | 0.6 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 50 | 1.0 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 158 | 3.2 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 133 | 2.7 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 2 | 0.0 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 30 | 0.6 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 123 | 2.5 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 261 | 5.3 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 197 | 4.0 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 283 | 5.7 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 90 | 1.8 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 172 | 3.5 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 270 | 5.5 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 202 | 4.1 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 210 | 4.2 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 505 | 10.2 | General function prediction only |

| S | 286 | 5.8 | Function unknown |

| - | 1664 | 33.7 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Susanne Schneider (DSMZ) for DNA extraction and quality analysis. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1.

While the manuscript was in editorial processing a 29th species in the genus Gordonia was published: G. hankookensis [49], which is not featured in Figure 1.

References

- 1.Tsukamura M. Proposal of a new genus, Gordona, for slightly acid-fast organisms occurring in sputa of patients with pulmonary disease and in soil. J Gen Microbiol 1971; 68:15-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodfellow M, Alderson G. The Actinomycete-genus Rhodococcus: A Home for the 'rhodochrous' Complex. J Gen Microbiol 1977; 100:99-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stackebrandt E, Smida J, Collins MD. Evidence of phylogenetic heterogeneity within the genus Rhodococcus: revival of the genus Gordona (Tsukamura). J Gen Appl Microbiol 1988; 34:341-348 10.2323/jgam.34.341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Euzéby JP. List of bacterial names with standing in nomenclature: A folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon JH, Lee J, Kang S, Takeuchi M, Shin Y, Lee S, Kang K, Park Y. Gordonia nitida sp. nov., a bacterium that degrades 3-ethylpyridine and 3-methylpyridine. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2000; 50:1203-1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell KS, Philp JC, Aw DWJ, Christofi N. The genus Rhodococcus. J Appl Microbiol 1998; 85:195-210 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue Y, Sun X, Zhou P, Liu R, Liang F, Ma Y. Gordonia paraffinivorans sp. nov., a hydrocarbon-degrading actinomycete isolated from an oil-producing well. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:1643-1646 10.1099/ijs.0.02605-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KK, Lee CS, Kroppenstedt RM, Stackebrandt E, Lee ST. Gordonia sihwensis sp. nov., a novel nitrate-reducing bacterium isolated from a wastewater-treatment bioreactor. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:1427-1433 10.1099/ijs.0.02224-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soddell JA, Stainsby FM, Eales KL, Seviour RJ, Goodfellow M. Gordonia defluvii sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from activated sludge foam. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:2265-2269 10.1099/ijs.0.64034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linos A, Steinbüchel A, Spröer C, Kroppenstedt RM. Gordonia polyisoprenivorans sp. nov., a rubber-degrading actinomycete isolated from an automobile tyre. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:1785-1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi M, Hatano K. Gordonia rhizosphera sp. nov. isolated from the mangrove rhizosphere. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1998; 48:907-912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kummer C, Schumann P, Stackebrandt E. Gordonia alkanivorans sp. nov., isolated from tar-contaminated soil. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:1513-1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen FT, Goodfellow M, Jones AL, Chen YP, Arun AB, Lai WA, Rekha PD, Young CC. Gordonia soli sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:2597-2601 10.1099/ijs.0.64492-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SB, Brown R, Oldfield C, Gilbert S, Iliarionov S, Goodfellow M. Gordonia amicalis sp. nov., a novel dibenzothiophene-desulphurizing actinomycete. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2000; 50:2031-2036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SB, Brown R, Oldfield C, Gilbert SC, Goodfellow M. Gordonia desulfuricans sp. nov., a benzothiophene-desulphurizing actinomycete. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:1845-1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodfellow M, Maldonado LA. 2006. The families Dietziaceae, Gordoniaceae, Nocardiaceae and Tsukamurellaceae In: F Dworkin, S Falkow, KH Schleifer E Stackebrandt (eds), The Prokaryotes, Archaea, Bacteria, Firmacutes, Actinomycetes, vol. 3. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoyama K, Kang Y, Yazawa K, Gonoi T, Kamei K, Mikami Y. Characterization of clinical isolates of Gordonia species in japanese clinical samples during 1998-2008. Mycopathologia 2009; 168:175-183 10.1007/s11046-009-9213-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sng LH, Koh TH, Toney SR, Floyd M, Butler WR, Tan BH. Bacteremia caused by Gordonia bronchialis in a patient with sequestrated lung. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:2870-2871 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2870-2871.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werno AM, Anderson TP, Chambers ST, Laird HM, Murdoch DR. Recurrent breast abscess caused by Gordonia bronchialis in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:3009-3010 10.1128/JCM.43.6.3009-3010.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richet HM, Craven PC, Brown JM, Lasker BA, Cox CD, McNeil MM, Tice AD, Jarvis WR, Tablan OC. A cluster of Rhodococcus (Gordona) bronchialis sternal-wound infections after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:104-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web Servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsukamura M. Identification of mycobacteria. Tubercle, London 1967; 48:311-338 10.1016/S0041-3879(67)80040-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsukamura M. Adansonian classification of mycobacteria. J Gen Microbiol 1966; 45:253-273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Editor L. Validation List No. 30. Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1989; 39:371 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wink JM. Compendium of Actinobacteria http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/wink_pdf/DSM43247.pdf 2009.

- 34.Agents B. Technical rules for biological agents www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 35.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chun J, Blackall LL, Kang S-O, Hah YC, Goodfellow M. A proposal to reclassify Nocardia pinensis Blackall et al. as Skermania piniformis gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:127-131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandão PFB, Maldonado LA, Ward AC, Bull AT, Goodfellow M. Gordonia namibiensis sp. nov., a novel nitrile metabolising actinomycete recovered from an African sand. Syst Appl Microbiol 2001; 24:510-515 10.1078/0723-2020-00074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.le Roes M, Goodwin CM, Meyers PR. Gordonia lacunae sp. nov., isolated from an estuary. Syst Appl Microbiol 2008; 31:17-23 10.1016/j.syapm.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alshamaony L, Goodfellow M, Minnikin DE, Mordarska H. Free mycolic acids as criteria in the classification of Gordona and the 'rhodochrous' complex. J Gen Microbiol 1976; 92:183-187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collins MD, Pirouz T, Goodfellow M, Minnikin DE. Distribution of menaquinones in actinomycetes and corynebacteria. J Gen Microbiol 1977; 100:221-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins MD, Goodfellow M, Minnikin DE, Alderson G. Menaquinone composition of mycolic acid-containing actinomycetes and some sporoactinomycetes. J Appl Bacteriol 1985; 58:77-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garton NJ, Sutcliffe IC. Identification of a lipoarabinomannan-like lipoglycan in the actinomycete Gordonia bronchialis. Arch Microbiol 2006; 184:425-427 10.1007/s00203-005-0050-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/ media_list.php

- 44.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova N, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter J, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anonymous. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. Oak Ridge National Laboratory and University of Tennessee 2009 http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal/

- 47.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. (Submitted). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park S, Kang SJ, Kim W, Yoon JH. Gordonia hankookensis sp. nov., isolated from soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:3172-3175 10.1099/ijs.0.011585-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]