Abstract

Dethiosulfovibrio peptidovorans Magot et al. 1997 is the type species of the genus Dethiosulfovibrio of the family Synergistaceae in the recently created phylum Synergistetes. The strictly anaerobic, vibriod, thiosulfate-reducing bacterium utilizes peptides and amino acids, but neither sugars nor fatty acids. It was isolated from an offshore oil well where it was been reported to be involved in pitting corrosion of mild steel. Initially, this bacterium was described as a distant relative of the genus Thermoanaerobacter, but was not assigned to a genus, it was subsequently placed into the novel phylum Synergistetes. A large number of repeats in the genome sequence prevented an economically justifiable closure of the last gaps. This is only the third published genome from a member of the phylum Synergistetes. The 2,576,359 bp long genome consists of three contigs with 2,458 protein-coding and 59 RNA genes and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: anaerobic, motile, vibrio-shaped, thiosulfate-reducing, H2S producing, peptide utilization, Synergistaceae, Synergistetes, GEBA

Introduction

Strain SEBR 4207T (= DSM 11002 = JCM 15826) is the type strain of the species Dethiosulfovibrio peptidovorans (‘curved rod-shaped [vibrio] bacterium that reduces thiosulfate devouring peptides’), which represents the type species of the genus Dethiosulfovibrio [1]. D. peptidovorans strain SEBR 4207T was isolated in 1989 from an offshore oil well in the Congo (Brazzaville) and initially described by Magot et al. in 1997 [1]. The strain provided the first experimental evidence for the involvement of microbial thiosulfate reduction in the corrosion of steel (pitting corrosion). Strain SEBR 4207T utilizes only peptides and amino acids, but no sugar or fatty acids. For the first few years neither the strain nor the genus Dethiosulfovibrio could be assigned to an established higher taxon, except that the distant relationship to the genus Thermanaerovibrio was reported [1]. The taxonomic situation of the species was only recently further enlightened, when Jumas-Bilak et al. [2] combined several genera with anaerobic, rod-shaped, amino acid degrading, Gram-negative bacteria into the novel phylum Synergistetes [2]. The phylum Synergistetes contains organisms isolated from humans, animals, terrestrial and oceanic habitats: Thermanaerovibrio, Dethiosulfovibrio, Aminiphilus, Aminobacterium, Aminomonas, Anaerobaculum, Jonquetella, Synergistes and Thermovirga. Given the novelty of the phylum it is not surprising that many of the type strains from these genera are already subject to genome sequencing projects. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for D. peptidovorans strain SEBR 4207T, together with the description of the genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

The 16S rRNA genes of the four other type strains in the genus Dethiosulfovibrio share between 94.2% (D. salsuginis [3]) and 99.2% (D. marinus [4]) sequence identity with strain SEBR 4207T, whereas the other type strains from the family Synergistaceae share 83.6 to 86.6% sequence identity [5]. There are no other cultivated strains that closely related. Uncultured clones with high sequence similarity to strain SEBR 4207T were identified in a copper-polluted sediment in Chile (clones LC6 and LC23, FJ024724 and FJ024721, 99.1%). Metagenomic surveys and environmental samples based on 16S rRNA gene sequences provide no indication for organisms with sequence similarity values above 88% to D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T, indicating that members of this species are not abundant in habitats screened thus far. The majority of these 16S rRNA gene sequences with similarity between 88% and 93% originate from marine metagenomes (status July 2010).

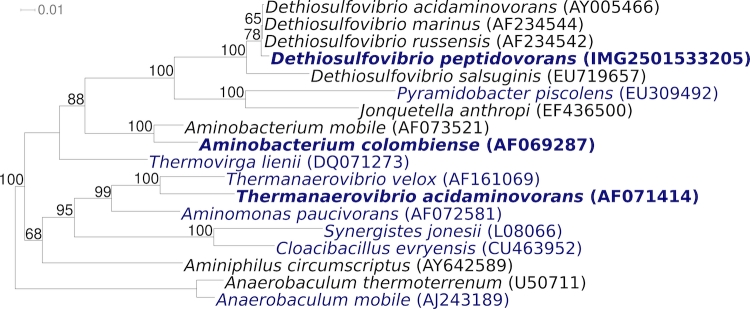

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The five copies of the 16S rRNA gene differ by up to one nucleotide from each other and by eight nucleotides from the previously published sequence generated from DSM 11002 (DPU52817).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T relative to the other type strains within the phylum Synergistetes. The tree was inferred from 1,328 aligned characters [6,7] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [8] and rooted in accordance with the current taxonomy [9]. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates if greater than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [10] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold [11,12].

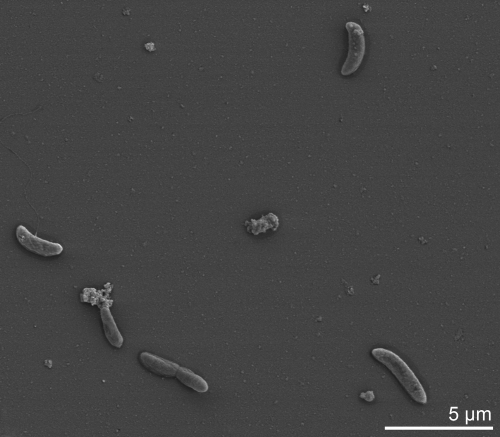

Cells of D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T stain Gram-negative [1]. Cells are vibriod with pointed or round ends and lateral flagella (Figure 2, flagella not visible) and a size of 3-5 by 1 µm [1] (Table 1). Spores were not detected [1]. Optimal growth rate was observed at 42°C, pH 7.0 in 3% NaCl [1]. D. peptidovorans is capable of utilizing peptides and amino acids as a sole carbon and energy source and can ferment serine and histidine. In the presence of thiosulfate, strain SEBR 4207T is capable of utilizing alanine, arginine, asparagines, glutamate, isoleucine, leucine, methionine and valine as an electron acceptor. The strain is capable of producing acetate, isobutyrate, isovalerate, 2-methylbutyrate, CO2 and H2 from peptides. The strain uses elemental sulfur and thiosulfate but not sulfate as electron acceptor. H2S is produced with a decrease in H2. Cells do not have cytochrome or desulfoviridin [1]. When yeast extract was added as sole carbon and energy source together with trypticase, thiosulfate was used as sole electron acceptor. Strain SEBR 4207T was not able to utilize gelatine, casein, arabinose, fructose, galactose, glucose, lactose, maltose, mannose, rhamnose, ribose, sucrose, sorbose, trehalose, xylose, acetate, propionate, butyrate, citrate and lactate.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T

Table 1. Classification and general features of D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T according to the MIGS recommendations [13].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [14] | |

| Phylum Synergistetes | TAS [2] | ||

| Class Synergistia | TAS [2] | ||

| Order Synergistales | TAS [2] | ||

| Family Synergistaceae | TAS [2] | ||

| Genus Dethiosulfovibrio | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Dethiosulfovibrio peptidovorans | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain SEBR 4207 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | curved rods (vibrioid) | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | motile via lateral flagella | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | mesophile, 20-45°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 42°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | slightly halophilic, optimum 3% NaCl | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | anaerobic | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | peptides and amino acids | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | peptides and amino acids | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | marine, oil wells | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | non pathogenic | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [15] | |

| Isolation | from corroding off-shore oil wells | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Emeraude oil field, Congo (Brazzaville) | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | before 1989 | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

-5.05 11.78 |

NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | about sea level | NAS |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [16]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Chemotaxonomy

None of the classical chemotaxonomic features (peptidoglycan structure, cell wall sugars, cellular fatty acid profile, menaquinones, or polar lipids) are known for D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T or any of the other members of the genus Dethiosulfovibrio.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [17], and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [18]. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [10] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Permanent draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One 8 kb pMCL200 Sanger library, one 454 pyrosequence standard library and one Solexa library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 Titanium, Illumina GAii |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 8.0 x Sanger; 55.0 x pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 1.1.02.15, Arachne |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | ABTR00000000 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | May 1, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01332 | |

| NCBI project ID | 20741 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501533205 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 11002 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

D. peptidovorans SEBR 4207T, DSM 11002, was grown anaerobically in DSMZ medium 786 (Dethiosulfovibrio peptidovorans Medium) [19] at 42°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the protocol as recommended by the manufacturer, with modification st/FT for cell lysis as described in Wu et al. [18].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the JGI website (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/). Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using Arachne assembler. Possible mis-assemblies were corrected and gaps between contgis were closed by primer walks off Sanger clones and bridging PCR fragments and by editing in Consed. A total of 392 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. Illumina reads were used to improve the final consensus quality using an in-house developed tool (the Polisher [20] ). The error rate of the final genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together, the combination of the Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms provided 63.0× coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 35,314 Sanger reads and 626,193 pyrosequencing reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [21] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [22]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [23].

Genome properties

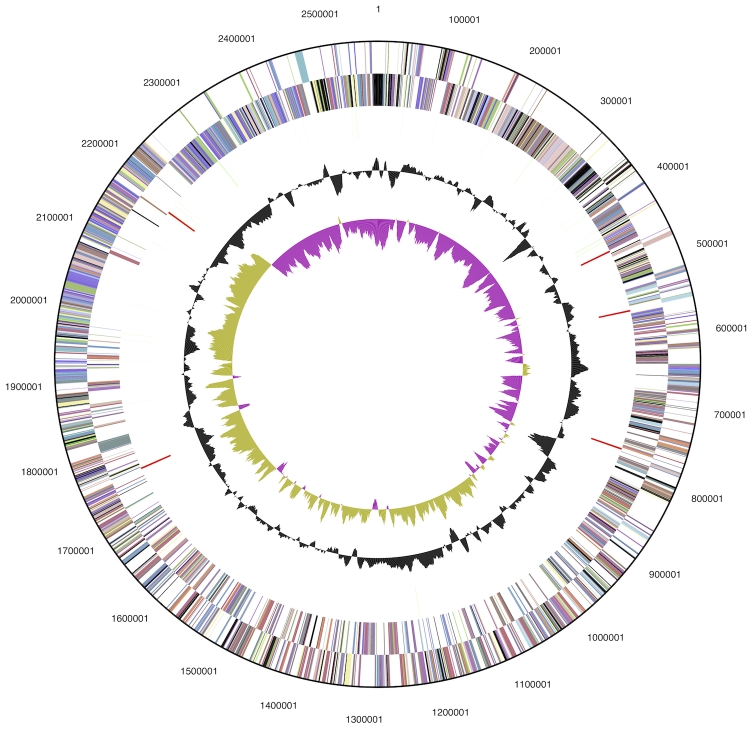

The genome is 2,576,359 bp long and assembled in one large contig and two small contigs (7,415 bp and 1,508 bp) with a 54.0% G+C content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 2,517 genes predicted, 2,458 were protein-coding genes, and 59 RNAs; No pseudogenes were identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (75.0%) were assigned with a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,576,359 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,391,158 | 92.81% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,401,945 | 54.42% |

| Number of repolicons | 3 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 2 | |

| Total genes | 2,517 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 59 | 1.40% |

| rRNA operons | 5 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,458 | 97.27% |

| Pseudo genes | 0 | 0.00% |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,888 | 75.01% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 438 | 17.41% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,952 | 77.55% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2,007 | 79.74% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 420 | 16.69% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 619 | 24.59% |

| CRISPR repeats | 2 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome (without the two small 1.5 and 7.4 kbp plasmids. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 149 | 6.7 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 129 | 5.9 | Transcription |

| L | 115 | 5.3 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 28 | 1.3 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 32 | 1.5 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 133 | 6.1 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 119 | 5.5 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 75 | 3.5 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 46 | 2.1 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 70 | 3.2 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 142 | 6.5 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 113 | 5.2 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 252 | 11.6 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 65 | 3.0 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 99 | 4.6 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 44 | 2.0 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 125 | 5.8 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 31 | 1.4 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 243 | 11.2 | General function prediction only |

| S | 161 | 7.4 | Function unknown |

| - | 565 | 22.5 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Esther Schüler for growing D. peptidovorans and Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis (both at DSMZ). This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, UT-Battelle and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-2. The Indian Council of Scientific and Industrial Research provided a Raman Research Fellowship to Shanmugam Mayilraj.

References

- 1.Magot M, Ravot G, Campaignolle X, Ollivier B, Patel BKC, Fardeau ML, Thomas P, Crolet JL, Garcia JL. Dethiosulfovibrio peptidovorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a new anaerobic, slightly halophilic, thiosulfate-reducing bacterium from corroding offshore oil wells. [9226912] Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:818-824; . 10.1099/00207713-47-3-818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jumas-Bilak E, Roudière L, Marchandin H. Description of 'Synergistetes' phyl. nov. and emended description of the phylum 'Deferribacteres' and of the family Syntrophomonadaceae, phylum 'Firmicutes'. [19406787] Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:1028-1035; . 10.1099/ijs.0.006718-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz-Cárdenas C, López G, Patel BKC, Baena S. Dethiosukfovibrio salsuginis sp. nov., an anaerobic slightly halophilic bacterium isolated from a saline spring in Colombia. Int J Syst Bacteriol 2009; (In press); . 10.1099/ijs.0.010835-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surkov AV, Dubinina GA, Lysenko AM, Glöckner FO, Kuever J. Dethiosulfovibrio russensis sp. nov., Dethiosulfovibrio marinus sp. nov. and Dethiosulfovibrio acidaminovorans sp. nov., novel anaerobic, thiosulfate- and sulfur-reducing bacteria isolated from 'Thiodendron' sulfur mats in different saline environments. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001; 51:327-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun J, Lee JH, Jung Y, Kim M, Kim S, Kim BK, Lim YW. EzTaxon: a web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:2259-2261 10.1099/ijs.0.64915-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web Servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yarza P, Richter M, Peplies J, Euzeby J, Amann R, Schleifer KH, Ludwig W, Glöckner FO, Rosselló-Móra R. The All-Species Living Tree project: a 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains. Syst Appl Microbiol 2008; 31:241-250 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chovatia M, Sikorski J, Schöder M, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Tice H, Glavina Del Rio T, Copeland A, Cheng JF, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Thermanaerovibrio acidaminovorans type strain (Su883T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:254-261 10.4056/sigs.40645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chertkov O, Sikorski J, Brambilla E, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Lucas S, Tice H, Cheng JF, et al. Complete genome sequence of Aminobacterium colombiense type strain (ALA-1T). Stand Genomic Sci 2010; 2:280-289 10.4056/sigs.902116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms. Proposal for the domains Archaea and Bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Classification of bacteria and archaea in risk groups. www.baua.de TRBA 466

- 16.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klenk HP, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol 2010; 33:175-182 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 20.Lapidus A, LaButti K, Foster B, Lowry S, Trong S, Goltsman E. POLISHER: An effective tool for using ultra short reads in microbial genome assembly and finishing. AGBT, Marco Island, FL, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A gene prediction improvement pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]