Abstract

Meiothermus ruber (Loginova et al. 1984) Nobre et al. 1996 is the type species of the genus Meiothermus. This thermophilic genus is of special interest, as its members share relatively low degrees of 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity and constitute a separate evolutionary lineage from members of the genus Thermus, from which they can generally be distinguished by their slightly lower temperature optima. The temperature related split is in accordance with the chemotaxonomic feature of the polar lipids. M. ruber is a representative of the low-temperature group. This is the first completed genome sequence of the genus Meiothermus and only the third genome sequence to be published from a member of the family Thermaceae. The 3,097,457 bp long genome with its 3,052 protein-coding and 53 RNA genes is a part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: thermophilic, aerobic, non-motile, free-living, Gram-negative, Thermales, Deinococci, GEBA

Introduction

Strain 21T (= DSM 1279 = ATCC 35948 = VKM B-1258) is the type strain of the species Meiothermus ruber, which is the type species of the genus Meiothermus [1]. Strain 21T was first described as a member of the genus Thermus by Loginova and Egorova in 1975 [2], but the species name to which it was assigned was not included on the Approved Lists of Bacterial Names [3]. Consequently Thermus ruber was revived, according to Rule 28a of the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria [4] in 1984 [5]. It received its current name in 1996 when transferred from the genus Thermus into the then novel genus Meiothermus by Nobre et al. [1]. Currently, there are eight species placed in the genus Meiothermus [6]. The genus name derives from the Greek words ‘meion’ and ‘thermos’ meaning ‘lesser’ and ‘hot’ to indicate an organism in a less hot place [1,6]. The species epithet derives from the Latin word ‘ruber’ meaning red, to indicate the red cell pigmentation [5,6]. Members of the genus Meiothermus were isolated from natural hot springs and artificial thermal environments [1] in Russia [5], Central France [7], both Northern and Central Portugal [8,9], North-Eastern China [10], Northern Taiwan [11] and Iceland [12]. Interestingly, the genus Meiothermus is heterogeneous with respect to pigmentation. The yellow pigmented species also form a distinct group on the basis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity, with the red/orange pigmented strains forming two groups, one comprising M. silvanus and the other the remaining species [9,10]. Like all members of the Deinococci the lipid composition of the cell membrane of members of the genus Meiothermus is based on unusual and characteristic structures. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for M. ruber 21T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

The 16S rRNA genes of the seven other type strains in the genus Meiothermus share between 88.7% (M. silvanus) [13] and 98.8% (M. taiwanensis) [14] sequence identity with strain 21T, whereas the other type strains from the family Thermaceae share 84.5 to 87.6% sequence identity [15]. Thermus sp. R55-10 from the Great Artesian Basin of Australia (AF407749), as well as other reference strains, e.g. 16105 and 17106 [12], and the uncultured bacterial clone 53-ORF05 from an aerobic sequencing batch reactor (DQ376569) show full length 16S rRNA sequences identical to that of strain 21T. A rather large number of isolates with almost identical 16S rRNA gene sequences originates from the Great Artesian Basin of Australia, clone R03 (AF407684), and various hot springs in Hyogo, Japan (strain H328; AB442017), Liaoning Province, China (strain L462; EU418906, and others), Thailand (strain O1DQU (EU376397), a Finnish paper production facility (strain L-s-R2A-3B.2; AM229096) and others), but also the not validly published ‘M. rosaceus’ (99.9%) [16] from Tengchong hot spring in Yunnan (China). Environmental samples and metagenomic surveys do not surpass 81-82% sequence similarity to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain 21T, indicating a rather mixed impression about the environmental importance of strains belonging to the species M. ruber, as occurring only in very restricted extreme habitats (status August 2009).

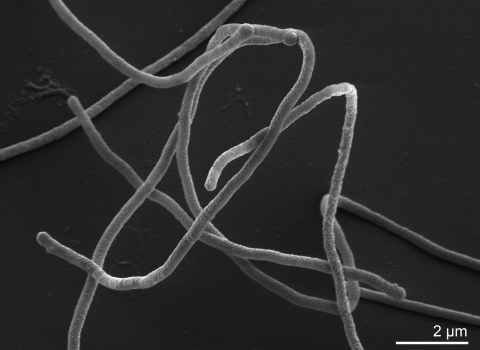

A detailed physiological description based on five strains has been given by Loginova et al. [5]. The cells are described as Gram-negative nonmotile rods that are 3 to 6 by 0.5 to 0.8 µm (Table 1), have rounded ends, and are nonsporeforming [5]. In potato-peptone-yeast extract broth incubated at 60°C, filamentous forms (20 to 40 µm in length) are observed along with shorter rods (Figure 1) [5]. No filamentous forms are observed after 16 h of incubation. M. ruber is obligately thermophilic [5]. On potato-peptone-yeast extract medium, the temperature range for growth is approx. 35-70°C, with an optimum temperature at 60°C (the generation time is then 60 min) [5]. A bright red intracellular carotenoid pigment is produced, which resembles retro-dehydro-γ-carotene (neo A, neo B) in its spectral properties [2]. The absorption spectra of acetone, methanol-acetone (l:l), and hexane extracts show three maxima at 455, 483, and 513 nm. The major carotenoid has since been identified as a 1‘-β-glucopyranosyl-3,4,3‘,4‘-tetradehydro-1‘,2‘-dihydro-β,ψ-caroten-2-one, with the glucose acetylated at position 6 [30]. One strain (strain INMI-a) contains a bright yellow pigment resembling neurosporaxanthine in its spectral properties [5], although it may well have been misidentified, since other species within the genus Meiothermus are yellow pigmented [8,9]. M. ruber is obligately aerobic [5]. It grows in minimal medium supplemented with 0.15% (wt/vol) peptone as an N source, 0.05% (wt/vol) yeast extract, and one of the following carbon sources at a concentration of 0.25% (wt/vol): D-glucose, sucrose, maltose, D-galactose, D-mannose, rhamnose, D-cellobiose, glycerol, D-mannitol, acetate, pyruvate, succinate, fumarate, or DL-malate (sodium salts). No growth occurs if the concentration of D-glucose in the medium is raised to 0.5% (wt/vol) [5]. Only moderate growth occurs when ammonium phosphate (0.1%, wt/vol) is substituted for peptone as the N source. No growth occurs in the control medium without a carbon source. No growth occurs on minimal medium supplemented with 0.25% (wt/vol) D-glucose, 0.05% (wt/vol) yeast extract and one of the following nitrogen sources at a concentration of 0.1% (wt/vol): L-alanine, glycine, L-asparagine, L-tyrosine, L-glutamate, ammonium sulfate, nitrate, or urea. Further lists of carbon source utilization, which differ in part from the above list, are published elsewhere [7,10-12]. Nitrates are not reduced and milk is not peptonized [5], but M. ruber strain 21T is positive for catalase and oxidase [10]. The most comprehensive and updated list of physiological properties is probably given by Albuquerque et al [7].

Table 1. Classification and general features of M. ruber 21T according to the MIGS recommendations [17].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [18] | |

| Phylum Deinococcus -Thermus | TAS [1,3,19-23] | ||

| Class Deinococci | TAS [24,25] | ||

| Order Thermales | TAS [25,26] | ||

| Family Thermaceae | TAS [25,27] | ||

| Genus Meiothermus | TAS [1,7] | ||

| Species Meiothermus ruber | TAS [5] | ||

| Type strain 21 | TAS [5] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [5] | |

| Cell shape | rod | TAS [5] | |

| Motility | non motile | TAS [5] | |

| Sporulation | not reported | TAS [5] | |

| Temperature range | 35°C–70°C | TAS [5] | |

| Optimum temperature | 60°C | TAS [5] | |

| Salinity | growth with 1% NaCl | TAS [7] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | obligately aerobic | TAS [5] |

| Carbon source | a diverse set of sugars | TAS [5] | |

| Energy source | carbohydrates | TAS [5] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | hot springs | TAS [5] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | TAS [5] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | not reported | |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [28] | |

| Isolation | hot spring | TAS [5] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia | TAS [5] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1973 or before | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

unknown unknown |

|

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | unknown | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | unknown |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [29]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements

Figure 1.

Scanning electron micrograph of M. ruber 21T

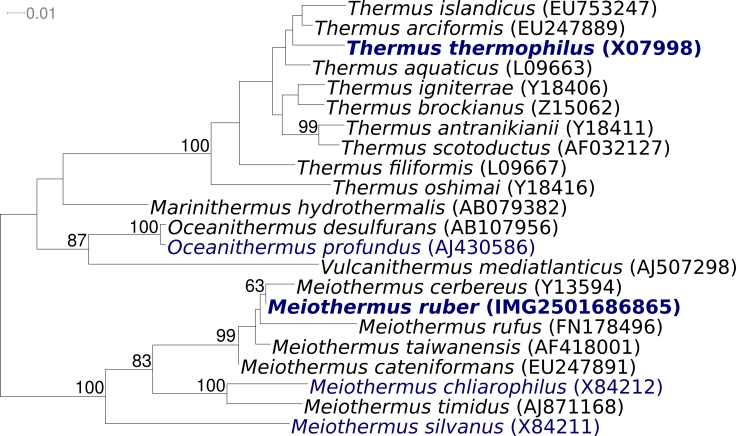

Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of M. ruber 21T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the two 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome are identical and differ by only one nucleotide from the previously published sequence generated from ATCC 35948 (Z15059).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of M. ruber 21T relative to the type strains of the other species within the genus and to the type strains of the other species within the family Thermaceae. The trees were inferred from 1,403 aligned characters [31,32] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [33] and rooted in accordance with the current taxonomy [34]. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates [35] if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [36] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold (Thermus thermophilus; AP008226).

Chemotaxonomy

Initial reports on the polar lipids of M. ruber indicated that they consist of two major glycolipids GL1a (~ 42%) and GL1b (~ 57%) and one major phospholipid PL2 (~ 93%), with small amounts of two other phospholipids PL1 and PL3 [37]. Detailed work indicates that in strains of Thermus oshimai, T. thermophilus, M. ruber, and M. taiwanensis the major phospholipid is a 2’-O-(1, 2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho) –3’-O-(α-N-acetyl-glucosaminyl)-N-glyceroyl alkylamine [38]. This compound is related to the major phosphoglycolipid reported from Deinococcus radiodurans [39] and can be considered to be unambiguous chemical markers for this major evolutionary lineage. The glycolipids are derivatives of a Glcp -> Glcp-> GalNAcyl -> Glcp -> diacyl glycerol [40]. Based on mass spectral data it appears that there may be three distinct derivatives, differing in the fatty acid amide linked to the gatactosamine [40]. These may be divided into one compound containing exclusively 2-hydroxylated fatty acids (mainly 2-OH iso-17:0) and a mixture of two compounds that cannot be fully resolved by thin layer chromatography carrying either 3-hydroxylated fatty acids or unsubstituted fatty acids. The basic glycolipid structure dihexosyl – N-acyl-hexosaminyl – hexosyl – diacylglycerol is a feature common to all members of the genera Thermus and Meiothermus examined to date. There is currently no evidence that members of the family Thermaceae (as currently defined) produce significant amounts of polar lipids containing only two aliphatic side chains. The consequences of having polar lipids containing three aliphatic side chains on membrane structure has yet to be examined. Such peculiarities also indicate the value of membrane composition in helping to unravel evolution at a cellular level. The major fatty acids of the polar lipids are iso-C15:0 (30-40%) and iso-C17:0 (13-17%), followed by anteiso-C15:0, C16:0, iso-C16:0, anteiso-C17:0, iso-C17:0-2OH, and, at least in some studies, iso-C17:1 ω9c (the values range from 3-10%). Other fatty acid values are below 2%, including 3-OH branched chain fatty acids. The values vary slightly between the different studies [7,9,11,12,37]. Detailed structural studies suggest that long chain diols may be present in small amounts, substituting for the 1-acyl-sn-glycerol [38]. Although not routinely reported the presence of alkylamines (amide linked to the glyceric acid of the major phospholipid) can be deduced from detailed structural studies of the major phospholipid [38]. Menaquinone 8 is the major respiratory quinone, although it is not clear which pathway is used for the synthesis of the naphthoquinone ring nucleus [41]. Ornithine is the major diamino acid of the peptidoglycan in the genus Meiothermus [1].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [42], and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [43]. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [36] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic libraries: one Sanger 8 kb pMCL200 library, one fosmide library and one 454 pyrosequence standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 9.84× Sanger; 27.4× pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 1.1.02.15, PGA |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001743 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | March 3, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01235 | |

| NCBI project ID | 28827 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501651201 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 1279 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

M. ruber 21T, DSM 1279, was grown in DSMZ medium 256 (Nutrient Agar) [44] at 50°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the standard protocol as recommended by the manufacturer, with modification L for cell lysis as described in Wu et al. [43].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the JGI website (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/). Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 3,428 overlap ping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using PGA assembler. Possible misassemblies were corrected and gaps between contgis were closed by primer walks off Sanger clones and bridging PCR fragments and by editing in Consed. A total of 431 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. Illumina reads were used to improve the final consensus quality using an in-house developed tool (the Polisher [45]). The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together, the combination of the Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms provided 37.24× coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 30,479 Sanger reads and 371,362 pyrosequencing reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [46] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [47]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [48].

Genome properties

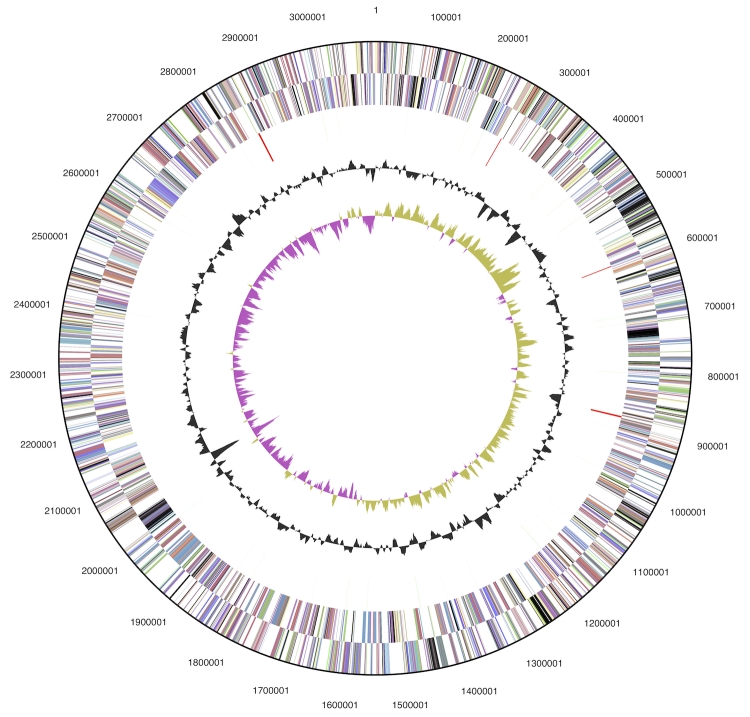

The genome consists of a 3,097,457 bp long chromosome with a 63.4% GC content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 3,105 genes predicted, 3,052 were protein-coding genes, and 53 RNAs; thirty eight pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (71.8%) were assigned with a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,097,457 | 100.00% |

| DNA Coding region (bp) | 2,807,535 | 90.64% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,963,304 | 63.38% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 3,105 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 53 | 1.71% |

| rRNA operons | 2 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 3,052 | 98.29% |

| Pseudo genes | 38 | 1.22% |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,229 | 71.79% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 390 | 12.56% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,286 | 73.62% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2,394 | 77.10% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,079 | 34.75% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 697 | 22.45% |

| CRISPR repeats | 6 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 146 | 5.8 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 131 | 5.2 | Transcription |

| L | 117 | 4.7 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.1 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 30 | 1.2 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 47 | 1.9 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 103 | 4.1 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 114 | 4.5 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 21 | 0.8 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 45 | 1.8 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 103 | 4.1 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 148 | 5.9 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 190 | 7.6 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 290 | 11.5 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 81 | 3.2 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 102 | 4.1 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 95 | 3.8 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 139 | 5.5 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 61 | 2.4 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 342 | 13.6 | General function prediction only |

| S | 208 | 8.3 | Function unknown |

| - | 819 | 26.4 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Susanne Schneider (DSMZ) for DNA extraction and quality analysis. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, UT-Battelle, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-2 and SI 1352/1-2.

References

- 1.Nobre MF, Trüper HG, Da Costa MS. Transfer of Thermus ruber (Loginova et al. 1984), Thermus silvanus (Tenreiro et al. 1995), and Thermus chliarophilus (Tenreiro et al. 1995) to Meiothermus gen. nov. as Meiothermus ruber comb. nov., Meiothermus silvanus comb. nov., and Meiothermus chliarophilus comb. nov., respectively, and emendation of the genus Thermus. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1996; 46:604-606 10.1099/00207713-46-2-604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loginova LG, Egorova LA. Obligate thermophilic-bacterium Thermus ruber in hot springs of Kamchatka. Mikrobiologiya 1975; 44:661-665 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapage SP, Sneath PHA, Lessel EF, Skerman VBD, Seeliger HPR, Clark WA. 1992. International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (1990 Revision). Bacteriological Code. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loginova LG, Egorova LA, Golovacheva RS, Seregina LM. Thermus ruber sp. nov., nom. rev. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1984; 34:498-499 10.1099/00207713-34-4-498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Euzéby JP. List of bacterial names with standing in nomenclature: A folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albuquerque L, Ferreira C, Tomaz D, Tiago I, Veríssimo A, da Costa MS, Nobre MF. Meiothermus rufus sp. nov., a new slightly thermophilic red-pigmented species and emended description of the genus Meiothermus. Syst Appl Microbiol 2009; 32:306-313 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tenreiro S, Nobre MF, da Costa MS. Thermus silvanus sp. nov. and Thermus chliarophilus sp. nov., two new species related to Thermus ruber but with lower growth temperatures. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995; 45:633-639 10.1099/00207713-45-4-633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pires AL, Albuquerque L, Tiago I, Nobre MF, Empadinhas N, Veríssimo A, da Costa MS. Meiothermus timidus sp. nov., a new slightly thermophilic yellow-pigmented species. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2005; 245:39-45 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang XQ, Zhang WJ, Wei BP, Xu XW, Zhu XF, Wu M. Meiothermus cateniformans sp. nov., a slightly thermophilic species from north-eastern China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:840-844 10.1099/ijs.0.007914-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen MY, Lin GH, Lin YT, Tsay SS. Meiothermus taiwanensis sp. nov., a novel filamentous, thermophilic species isolated in Taiwan. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1647-1654 10.1099/ijs.0.02189-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung AP, Rainey F, Nobre MF, Burghardt J, Costa MSD. Meiothermus cerbereus sp. nov., a new slightly thermophilic species with high levels of 3-hydroxy fatty acids. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:1225-1230 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nobre MF, Trüper HG. Da Costa. Transfer of Thermus ruber (Loginova et al. 1984), Thermus silvanus (Tenreiro et al. 1995), and Thermus chliarophilus (Tenreiro et al. 1995) to Meiothermus gen. nov. as Meiothermus ruber comb. nov., Meiothermus silvanus comb. nov., and Meiothermus chliarophilus comb. nov., respectively, and emendation of the genus Thermus. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1996; 46:604-606 10.1099/00207713-46-2-604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen MY, Lin GH, Lin YT, Tsay SS. Meiothermus taiwanensis sp. nov., a novel filamentous, thermophilic species isolated in Taiwan. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1647-1654 10.1099/ijs.0.02189-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chun J, Lee JH, Jung Y, Kim M, Kim S, Kim BK, Lim YW. EzTaxon: a web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:2259-2261 10.1099/ijs.0.64915-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Lin L, Peng Q, Ben K, Zhou Z. Meiothermus rosaceus sp. nov. isolated from Tengchong hot spring in Yunnan, China. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2002; 216:263-268 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11445.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrity GM, Lilburn TG, Cole JR, Harrison SH, Euzéby J, Tindall BJ. Taxonomic outline of the Bacteria and Archaea, Release 7.7 March 6, 2007. Part 2 - The Bacteria: Phyla "Aquificae", "Thermotogae", "Thermodesulfobacteria", "Deinococcus-Thermus", "Chrysiogenetes", "Chloroflexi", "Thermomicrobia", "Nitrospira", "Deferribacteres", "Cyanobacteria", and "Chlorobi". http://www.taxonomicoutline.org/index.php/toba/article/view/187/211

- 20.Weisburg WG, Giovannoni SJ, Woese CR. The Deinococcus-Thermus phylum and the effect of rRNA composition on phylogenetic tree construction. Syst Appl Microbiol 1989; 11:128-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks BW, Murray RGE. Nomenclature for Micrococcus radiodurans and other radiation resistant cocci: Deinococcaceae fam. nov. and Deinococcus gen. nov., including five species. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1981; 31:353-360 10.1099/00207713-31-3-353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rainey FA, Nobre MF, Schumman P, Stackebrandt E, da Costa MS. Phylogenetic diversity of the deinococci as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence comparison. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:510-514 10.1099/00207713-47-2-510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brock TD, Freeze H. Thermus aquaticus gen. n. and sp. n., a nonsporulating extreme thermophile. J Bacteriol 1969; 98:289-297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrity GM, Holt JG. Class I. Deinococci class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 395. [Google Scholar]

- 25.List Editor Validation List no. 85. Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:685-690 10.1099/ijs.0.02358-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rainey FA, da Costa MS. Order II. Thermales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 403. [Google Scholar]

- 27.da Costa MS, Rainey FA. Family I. Thermaceae fam. nov. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 403-404. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Classification of bacteria and archaea in risk groups. www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 29.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burgess ML, Barrow KD, Gao C, Heard GM, Glenn D. Carotenoid glycoside esters from the thermophilic bacterium Meiothermus ruber. J Nat Prod 1999; 62:859-863 10.1021/np980573d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web Servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yarza P, Richter M, Peplies J, Euzeby JP, Amann R, Schleifer KH, Ludwig W, Glöckner FO, Rossello-Mora R. The All-Species Living Tree project: A 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains. Syst Appl Microbiol 2008; 31:241-250 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donato ME, Seleiro EA, da Costa MS. Polar lipid and fatty acid composition of strains of Thermus ruber. Syst Appl Microbiol 1991; 14:234-239 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang YL, Yang FL, Jao SC, Chen MY, Tsay SS, Zou W, Wu SH. Structural elucidation of phosphoglycolipids from strains of the bacterial thermophiles Thermus and Meiothermus. J Lipid Res 2006; 47:1823-1832 10.1194/jlr.M600034-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson R, Hansen K. Structure of a novel phosphoglycolipid from Deinococcus radiodurans. J Biol Chem 1985; 260:12219-12223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferreira AM, Wait R, Nobre MF, da Costa MS. Characterization of glycolipids from Meiothermus spp. Microbiology 1999; 145:1191-1199 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiratsuka T, Furihata K, Ishikawa J, Yamashita H, Itoh N, Seto H, Dairi T. An alternative menaquinone biosynthetic pathway operating in microorganisms. Science 2008; 321:1670-1673 10.1126/science.1160446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klenk HP, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol 2010; 33:175-182 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 45.Lapidus A, LaButti K, Foster B, Lowry S, Trong S, Goltsman E. POLISHER: An effective tool for using ultra short reads in microbial genome assembly and finishing. AGBT, Marco Island, FL, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A gene prediction improvement ipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]