Abstract

Nakamurella multipartita (Yoshimi et al. 1996) Tao et al. 2004 is the type species of the monospecific genus Nakamurella in the actinobacterial suborder Frankineae. The nonmotile, coccus-shaped strain was isolated from activated sludge acclimated with sugar-containing synthetic wastewater, and is capable of accumulating large amounts of polysaccharides in its cells. Here we describe the features of the organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. This is the first complete genome sequence of a member of the family Nakamurellaceae. The 6,060,298 bp long single replicon genome with its 5415 protein-coding and 56 RNA genes is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: polysaccharide-accumulating, septa-forming, nonmotile, Gram-positive, MK-8 (H4), ‘Microsphaeraceae’, Frankineae, GEBA

Introduction

Strain Y-104T [1] (DSM 44233 = ATCC 700099 = JCM 9533) is the type strain of the species Nakamurella multipartita, which is the sole member and type species of the genus Nakamurella [2], the type genus of the family Nacamurellaceae [2]. N. multipartita was first described in 1996 by Yoshimi et al. as polysaccharide-accumulating ‘Microsphaera multipartita’ and type species of the genus ‘Microsphaera’ [1]. Unfortunately, Yoshimi et al. [1] overlooked the priority of the named fungal genus Microsphaera described 145 years earlier [3]. Principle 1(2) of the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (1990 Revision) recommends avoiding the use of names which might cause confusion and therefore grants priority of the fungal genus Microsphaera in the family Erysiphaceae [4], Stackebrandt et al. maintained the illegitimate name when creating the likewise illegitimate family ‘Microsphaeraceae’ in 1997 [5]. In 2004 Tao et al. replaced the illegitimate genus and family names with the legitimate and validly published names Nakamurella and Nakamurellaceae, respectively, in honor of the Japanese microbiologist Kazonuri Nakamura, who also discovered strain Y-104T [2]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for N. multipartita strain Y-104T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features of organism

The environmental diversity of the members of the species N. multipartita appears to be limited. Only one 16S rRNA gene sequence from a Finish indoor isolate (BF0001B070, 96.2% sequence identity) is reported in Genbank [6], as well as two Finish indoor phylotypes (FM872655, 98.2%; FM873571, 96.2%) by Taubel et al., and a phylotype from fresh water sediment of the high altitude Andean Altiplano (northern Chile) with 96.6% sequence identity (EF632902). None of the sequences generated from large scale environmental samplings and genome surveys surpassed 93% sequence identity and were thereby significantly less similar to strain Y-104T than the closest related type strain, DS-52 T of Humicoccus flavidus (95.9%) [7] (status November 2009).

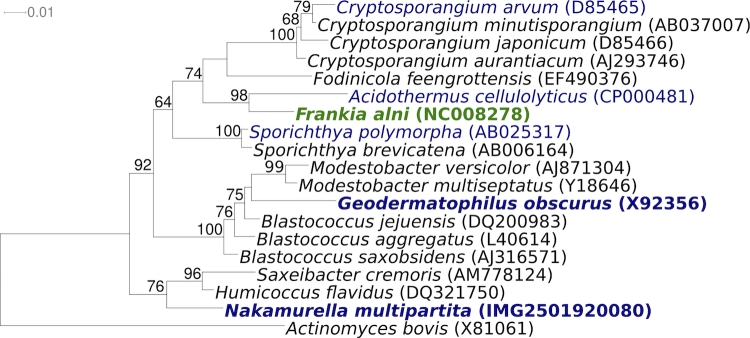

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of N. multipartita strain Y-104T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the two identical 16S rRNA gene copies differ by one nucleotide (C-homopolymer close to 3’-end) from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence generated from JCM 9543 (Y08541).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of N. multipartita Y-104T relative to the other type strains within the Frankineae. The tree was inferred from 1362 aligned characters [8,9] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [10] and rooted with the type strain of the order. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [11] such as the GEBA organism Geodermatophilus obscurus [12] are shown in blue. Important non-type strains are shown in green [13], and published genomes in bold.

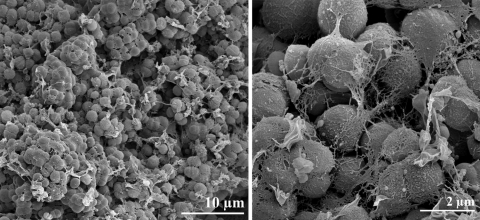

N. multipartita strain Y-104T is aerobic and chemoorganotrophic. Cells are non-motile, non-spore forming, Gram-positive (Table 1) and coccus-shaped [1]. The cells are 0.8 to 3.0 µm in diameter; depending on the growth stage. They occur as singles, in pairs or in small irregular clusters (Figure 2). A rod-coccus cycle was not observed at any stage of the growth. Strain Y-104T has a characteristic cell division in which a cell wall-like structure occurs in the middle of each cell during their early growth phase. Such structures, also called septa, were frequently observed during the late log phase of the growth cycle [1]. The doubling time was reported to be approximately 11 hours in a liquid medium at pH 7.0 and at 25°C [1]. Colonies on agar plates are circular, smooth, convex and white at the early stage of growth and cream-colored at later stage of growth. The polysaccharide content of the cells is very high, sometimes more than 50% (wt/wt) depending on the culture conditions.

Table 1. Classification and general features of N. multipartita strain Y-104T according to the MIGS recommendations [14].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria Phylum Actinobacteria Class Actinobacteria Order Actinomycetales Suborder Frankineae Family Nakamurellaceae Genus Nakamurella Species Nakamurella multipartita Type strain Y-104 |

TAS [15] TAS [16] TAS [5] TAS [5] TAS [2] TAS [2] TAS [2] TAS [2] TAS [1] |

|

| Gram stain | positive | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | coccus | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | non-motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | 10-35°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 25°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | up to 6g NaCl/L | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | aerobic chemoorganotroph | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | sugars, alcohols, glucose, maltose, mannose, fructose, starch |

TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | starch, ethanol, propanol | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | activated sludge cultured in fed-batch reactors | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [17] | |

| Isolation | activated sludge | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | not reported | |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [18]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a live isolate by one of the authors, or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of N. multipartita strain Y-104T

Growth of strain Y-104T occurs at a temperature range of 10-35˚C and a pH range of 5.0 to 9.0 and in the presence of up to 6% NaCl. N. multipartita is positive for catalase production and negative for oxidase activity [1]. It is capable of utilizing glucose, fructose, mannose, galactose, xylose, sucrose, maltose, lactose, mannitol, sorbitol, ethanol, propanol, glycerol, starch, pyruvate, aranine, glutamate, glutamine and histidine as carbon and energy sources [1]. The strain cannot utilize acetate, malate, succinate, arginine, asparagine, methanol or glycogen as carbon and energy sources [1]. Strain Y-104T is able to accumulate large amounts of polysaccharides in its cells [1].

Chemotaxonomy

The murein of N. multipartita strain Y-104T contains meso-diaminopimelic acid as the diagnostic diamino acid [1]. The fatty acid pattern of Y-104T is dominated by iso-C16:0 (19.7%), iso-C15:0 (15.7%) and C18:1 (14.0%) and substantial amounts of C16:0 (10.3%), anteiso-C15:0 (9.2%), iso-C17:0 (8.5%) and anteiso-C17:0 (5.2%) were detected [1]. The predominant menaquinones are MK-8 (H4), approximately 97.0%, and minor amounts of MK-7 (H4), MK-8 (H2) and MK-9 (H4) were present [1]. Mycolic acids are absent [1].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of each phylogenetic position, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [14] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two Sanger genomic libraries: 8kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 15.4× Sanger |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Arachne, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001737 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | September 18, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi02230 | |

| NCBI project ID | 29537 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501939634 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 44233 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

N. multipartita Y-104T, DSM 44233, was grown in DSMZ 553 medium [19] at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 1-1.5 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions with modification st/FT for cell lysis according to Wu et al. [20].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using Sanger sequencing platform. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found on the JGI website. Optimal raft assembly was produced using Arachne assembler. Finishing assemblies were made using the parallel phrap assembler (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher [21] or transposon bombing of bridging clones (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 2,596 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together all Sanger reads provided 15.4× coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 118,931 Sanger reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [22] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePrimp pipeline [23]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [24].

Genome properties

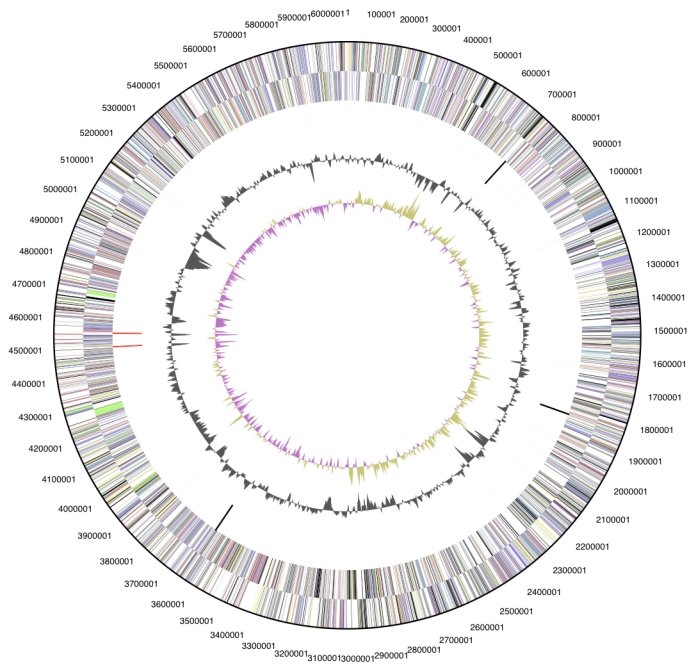

The genome is 6,060,298 bp long and comprises one main circular chromosome with a 70.9% G+C content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 5,471 genes predicted, 5,415 were protein coding genes, and 56 RNAs; 175 pseudo genes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (66.5%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 6,060,298 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 5,526,464 | 91.19% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 4,297,749 | 70.92% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 5,471 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 56 | 1.02% |

| rRNA operons | 2 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 5,415 | 98.98% |

| Pseudo genes | 175 | 3.20% |

| Genes with function prediction | 3,638 | 66.50% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 3,319 | 60.67% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,673 | 67.14% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 4,054 | 74.10% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,713 | 31.31% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,258 | 22.99% |

| CRISPR repeats | 9 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 160 | 3.9 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 2 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 400 | 9.7 | Transcription |

| L | 324 | 7.8 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| D | 31 | 0.8 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| V | 81 | 2.0 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 238 | 5.8 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 173 | 4.2 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| Z | 1 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| U | 44 | 1.1 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 113 | 2.7 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 308 | 7.5 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 341 | 8.3 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 334 | 8.1 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 97 | 2.4 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 190 | 4.6 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 160 | 3.9 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 182 | 4.4 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 117 | 2.8 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 506 | 12.2 | General function prediction only |

| S | 330 | 8.0 | Function unknown |

| - | 1773 | 32.4 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Marlen Jando for growing N. multipartita cells, and Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis (both at DSMZ). This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1 and the Indian Council of Scientific and Industrial Research provided a Raman Research Fellow to Shanmugam Mayilraj.

References

- 1.Yoshimi Y, Hiraishi A, Nakamura K. Isolation and characterization of Microsphaera multipartita gen. nov., sp. nov., a polysaccharide-accumulating Gram-positive bacterium from activated sludge. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1996; 46:519-525 10.1099/00207713-46-2-519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao TS, Yue YY, Chen WX, Chen WF. Proposal of Nakamurella gen. nov. as a substitute for the bacterial genus Microsphaera Yoshimi et al. 1996 and Nakamurellaceae fam. nov. as a substitute for the illegitimate bacterial family Microsphaeraceae Rainey et al. 1997. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004; 54:999-1000 10.1099/ijs.0.02933-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Léveillé JH. Organisation et disposition méthodique des especes qui composent le genre Erysiphé. Ann Sci Nat Bot Ser 1851; 15:109-179 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapage SP, Sneath PHA, Lessel EF, Skerman VBD, Seeliger HPR, Clark WA, eds. International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (1990 revision). Bacteriological Code American Society for Microbiology, Washington DC, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rintala H, Pitkaranta M, Toivola M, Paulin L, Nevalainen A. Diversity and seasonal dynamics of bacterial community in indoor environment. BMC Microbiol 2008; 8:56 10.1186/1471-2180-8-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon JH, Kang SJ, Jung SY, Oh TK. Humicoccus flavidus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:56-59 10.1099/ijs.0.64246-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web-servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanova N, Sikorski J, Jando M, Munk C, Lapidus A, Glavina Del Rio T, Copeland A, Tice H, Cheng JF, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Geodermatophilus obscurus type strain (G-20T). Stand Genomic Sci 2010; (This issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Normand P, Lapierre P, Tisa LS, Gogarten JP, Alloisio N, Bagnarol E, Bassi CA, Berry AM, Bickhart DM, Choisne N, et al. Cenome characteristics of facultatively symbiontic Frankia sp. strains reflect host range and host plant biogeography. Genome Res 2006; 17:7-15 10.1101/gr.5798407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen JA, Angiuoli SV, et al. Towards a richer description of our complete collection of genomes and metagenomes: the “Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence” (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biological Agents. Classification of Bacteria and Archaea in risk groups. www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 18.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/ media_list.php

- 20.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova N, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic en-cyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter J, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods (In press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]