Abstract

Sulfurospirillum deleyianum Schumacher et al. 1993 is the type species of the genus Sulfurospirillum. S. deleyianum is a model organism for studying sulfur reduction and dissimilatory nitrate reduction as an energy source for growth. Also, it is a prominent model organism for studying the structural and functional characteristics of cytochrome c nitrite reductase. Here, we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. This is the first completed genome sequence of the genus Sulfurospirillum. The 2,306,351 bp long genome with its 2,291 protein-coding and 52 RNA genes is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: anaerobic, microaerobic, sulfur reduction, dissimilatory nitrate reduction, Gram-negative, motile, Campylobacteraceae, GEBA

Introduction

Strain 5175T (= DSM 6946 = ATCC 51133 = LMG 8192) is the type strain of the species Sulfurospirillum deleyianum, which is the type species of the genus Sulfurospirillum. The genus Sulfurospirillum was originally proposed by Schumacher et al. in 1992 [1]. The generic name Sulfurospirillum derives from the chemical element ‘sulfur’ and ‘spira’ from Latin meaning coil, a coiled bacterium that reduces sulfur [2]. The species is named after J. De Ley, a Belgian microbiologist who significantly contributed to bacterial systematics based on genetic relationships [3]. Altogether, the genus Sulfurospirillum contains seven species [2]. Strain 5175T was isolated from anoxic mud of a forest pond near Heinigen, Braunschweig area, Germany [3]. It is unclear if further isolates of the species exist. Here, we present a summary classification and a set of features for S. deleyianum 5175T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

There were several uncultured clone sequences known in INSDC databases with at least 98% sequence identity to the 16S rRNA gene sequence (Y13671) of strain S. deleyianum 5175T. These were obtained from lake material in Dongping, China (FJ612333), deep subsurface groundwater in Japan (AB237694), and from the mangrove ecosystem of the Danshui River Estuary of Northern Taiwan (DQ234237) [4]. No significant matches were reported with metagenomic samples at the NCBI BLAST server (November 2009).

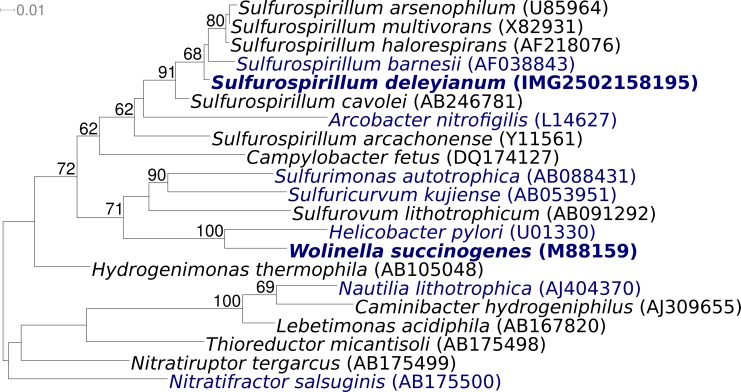

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of S. deleyianum 5175T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the three 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome of S. deleyianum 5175T differ from each other by no more than one nucleotide, and differ by no more than one nucleotide from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (Y13671).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of S. deleyianum 5175T relative to the other type strains within the genus and the type strains of the other genera within the class Epsilonproteobacteria. The tree was inferred from 1,326 aligned characters [5,6] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [7] and rooted with the Nautiliales. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 450 bootstrap replicates if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [8] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold.

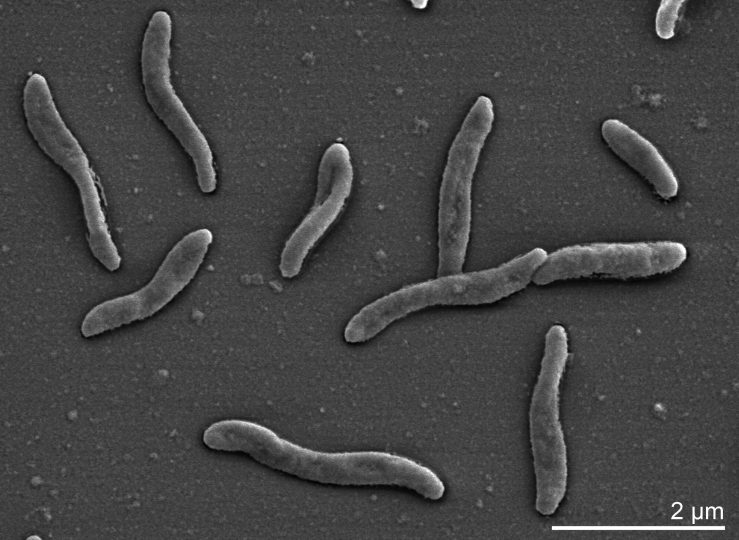

The cells of strain 5175T are curved spiral rods of approximately 0.3-0.5 µm width and 1.0-3.0 µm length [1], with polar flagellation (Table 1 and Figure 2). Colonies are yellow-colored as a result of a flexirubin-type pigment [17]. The cells contain cytochrome b and c [4]. Strain 5175T is unable to rapidly decompose H2O2 (i.e. is catalase negative), does not need special growth factors (vitamins or amino acids), and is positive for oxidase [1]. Strain 5175T grows anoxically with hydrogen, formate, fumarate, and pyruvate, but not lactate, as electron donor; acetate and hydrogen carbonate as carbon source and one of the following electron acceptors: nitrate, nitrite (which is reduced to ammonia), sulfite, thiosulfate, elemental sulfur (reduced to sulfide), dimethyl sulfoxide (reduced to dimethyl sulfide), fumarate, malate and aspartate (reduced to succinate) [1,18]. Sulfate is not reduced. Fumarate and malate can be fermented [1]. Strain 5175T is able to grow microaerobically at 1-4% oxygen, but not at 21% oxygen [1]. The substrates utilized for microaerobic growth are succinate, fumarate, malate, aspartate, pyruvate, oxoglutarate, and oxaloacetate [1]. There is no oxidation of glycerol or acetate [1]. An assimilatory sulfate reduction is lacking, and a source of reduced sulfur, e.g. sulfide [19] or L-cysteine, is required for growth [1]. Further characteristics of the sulfur respiration of strain 5175T have been studied in detail [4,20].

Table 1. Classification and general features of S. deleyianum 5175T according to the MIGS recommendations [9].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [10] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [11] | ||

| Class Epsilonproteobacteria | TAS [12] | ||

| Order Campylobacterales | TAS [12] | ||

| Family Campylobacteraceae | TAS [13] | ||

| Genus Sulfurospirillum | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Sulfurospirillum deleyianum | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain 5175 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | curved spiral rods | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | motile by polar flagellum | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | 20°C-36°C, no growth at 42°C | TAS [14] | |

| Optimum temperature | 30°C | NAS | |

| Salinity | < 0.2% | TAS [14] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | anaerobic, microaerobic (1-4% oxygen) | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | dicarboxylic acids, aspartate, pyruvate, acetate, hydrogen carbonate |

TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | dicarboxylic acids, aspartate, pyruvate, formate, H2, H2S |

TAS [1,3] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | anoxic mud | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [15] | |

| Isolation | anoxic mud from a German lake | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Heinigen near Wolfenbüttel | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1976 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

52.17 10.55 |

NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [16]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property should have been directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of S. deleyianum 5175T

Observations of ferric iron-reducing bacteria indicated that ferrihydrite was reduced to ferrous iron minerals via sulfur cycling with sulfide as the reductant. Ferric iron reduction via sulfur cycling was investigated in more detail with strain 5175T, which can utilize sulfur or thiosulfate as an electron acceptor [21]. In the presence of cysteine (0.5 or 2 mM) as the sole sulfur source, no (microbial) reduction of ferrihydrite or ferric citrate was observed, indicating that S. deleyianum is unable to use ferric iron as an immediate electron acceptor [21]. Interestingly, with thiosulfate at low concentration (0.05 mM), growth with ferrihydrite (6 mM) was possible, and sulfur was cycled up to 60 times [21].

An interesting syntrophism between strain 5175T and Chlorobium limicola 9330 has been reported [22]. The substrate formate is not metabolized by Chlorobium, and the limiting amount of sulfur is alternately reduced by strain 5175T and oxidized by Chlorobium [22].

With respect to utilization of nitrate as terminal electron acceptor (dissimilatory nitrate reduction) [3] the dissimilatory hexaheme c nitrite has been studied in more detail. These include both structural and functional aspects [23-26].

Also, strain 5175T is able to use alternative electron acceptors. Strain 5175T is able to reduce the quinone moiety of anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) and also to oxidize reduced anthrahydroquinone-2,6,-disulfonate (AH2QDS) as well [27]. Additionally, oxidized metals may be used as terminal electron acceptors, such as arsenate [As(V)] and manganese [Mn(IV)], but not selenate [Se(VI)] or ferric iron [Fe(III)] [27].

Chemotaxonomy

The predominant menaquinone is MK-6 (88%), with small amounts of thermoplasmaquinone with six isoprene units (TPQ-6; 10%) and MK-5 (2%) [28]. The polar-lipid fatty acid composition is 16:1ω7c (52.0%), 16:0 (29.2%), 18:1ω7c (17.2%), 15:0 (1.1%), and iso16:1 (0.6%) [29].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [31]. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [10] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One Sanger libraries 8 kb pMCL200 and One 454 pyrosequence standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 GS FLX |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 9.12× Sanger, 25.3× pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001816 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | November 18, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01143 | |

| NCBI project ID | 29529 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2502082112 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 6946 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

S. deleyianum 5175T, DSM 6946, was grown anaerobically in DSM medium 541 [30] at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol with modification st/L for cell lysis as described in Wu et al. [31].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at http://www.jgi.doe.gov/. 454 Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 2,525 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and to adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using the phrap assembler. Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones [32]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 471 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together all sequence types provided 34.42× coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 23,491 Sanger and 296,611 pyrosequence reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [33] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [34]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [35].

Genome properties

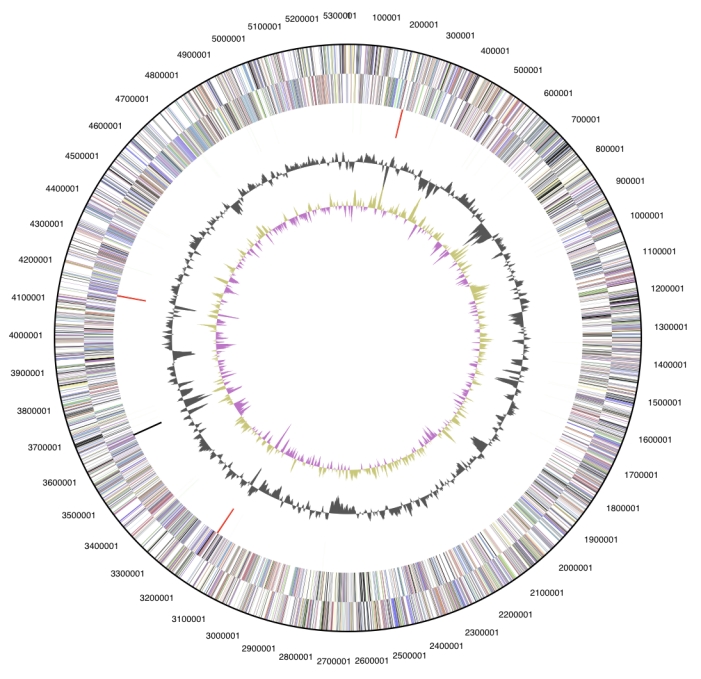

The genome consists of a 2,306,351 bp long chromosome with a 39.0% GC content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 2,343 genes predicted, 2,291 were protein coding genes, and 52 RNAs. A total of 26 pseudogenes were identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (72.9%) were assigned with a putative function while those remaining were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,306,351 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,171,873 | 94.17% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 898,781 | 38.97% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 2,343 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 52 | 2.22% |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,291 | 97.78% |

| Pseudo genes | 26 | 1.11% |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,708 | 72,90% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 254 | 10.84% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,724 | 73.58% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 1,750 | 74.69% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 439 | 18.74% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 566 | 24.16% |

| CRISPR repeats | 2 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 141 | 6.2 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 88 | 3.8 | Transcription |

| L | 113 | 4.9 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 25 | 1.1 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 27 | 1.1 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 181 | 7.9 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 128 | 5.6 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 83 | 3.6 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 61 | 2.7 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 85 | 3.7 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 150 | 6.5 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 53 | 2.3 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 154 | 6.7 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 51 | 2.2 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 101 | 4.4 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 43 | 1.9 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 112 | 4.9 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 21 | 0.9 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 194 | 8.5 | General function prediction only |

| S | 119 | 5.2 | Function unknown |

| - | 619 | 27.0 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Petra Aumann in cultivation of the strain and Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis (both at DSMZ). This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1 and SI 1352/1-2.

References

- 1.Schumacher W, Kroneck PMH, Pfennig N. Comparative systematic study on "Spirillum" 5175, Campylobacter and Wolinella species. Arch Microbiol 1992; 158:287-293 10.1007/BF00245247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Euzéby JP. List of bacterial names with standing in nomenclature: A folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schumacher W, Kroneck P. Anaerobic energy metabolism of the sulfur-reducing bacterium "Spirillum" 5175 during dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia. Arch Microbiol 1992; 157:464-470 10.1007/BF00249106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao PC, Huang BH, Huang S. Microbial community composition of the Danshui river estuary of Northern Taiwan and the practicality of the phylogenetic method in microbial barcoding. Microb Ecol 2007; 54:497-507 10.1007/s00248-007-9217-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web Servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Order I. Campylobacterales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1145. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandamme P, De Ley J. Proposal for a new family, Campylobacteraceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1991; 41:451-455 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodama Y, Ha LT, Watanabe K. Sulfurospirillum cavolei sp. nov., a facultatively anaerobic sulfur-reducing bacterium isolated from an underground crude oil storage cavity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:827-831 10.1099/ijs.0.64823-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biological Agents. Technical rules for biological agents www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 16.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zöphel A, Kennedy MC, Beinert H, Kroneck PM. Investigations on microbial sulfur respiration. Isolation, purification, and characterization of cellular components from Spirillum 5175. Eur J Biochem 1991; 195:849-856 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolz JF, Ellis DJ, Blum JS, Ahmann D, Lovley DR, Oremland RS. Sulfurospirillum barnesii sp. nov. and Sulfurospirillum arsenophilum sp. nov., new members of the Sulfurospirillum clade of the ε-Proteobacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:1177-1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenmann E, Beuerle J, Sulger K, Kroneck P, Schumacher W. Lithotrophic growth of Sulfurospirillum deleyianum with sulfide as electron donor coupled to respiratory reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Arch Microbiol 1995; 164:180-185 10.1007/BF02529969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straub KL, Schink B. Ferrihydrite-dependent growth of Sulfurospirillum deleyianum through electron transfer via sulfur cycling. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004; 70:5744-5749 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5744-5749.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zöphel A, Kennedy MC, Beinert H, Kroneck PMH. Investigations on microbial sulfur respiration. Activation and reduction of elemental sulfur in several strains of eubacteria. Arch Microbiol 1988; 150:72-77 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe RS, Pfennig N. Reduction of sulfur by spirillum 5175 and syntrophism with Chlorobium. Appl Environ Microbiol 1977; 33:427-433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Einsle O, Messerschmidt A, Stach P, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Huber R, Kroneck PMH. Structure of cytochrome c nitrite reductase. Nature 1999; 400:476-480 10.1038/22802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumacher W, Kroneck PMH. Dissimilatory hexaheme c nitrite reductase of "Spirillum" strain 5175: purification and properties. Arch Microbiol 1991; 156:70-74 10.1007/BF00418190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stach P, Einsle O, Schumacher W, Kurun E. M.H. Kroneck P. Bacterial cytochrome c nitrite reductase: new structural and functional aspects. J Inorg Biochem 2000; 79:381-385 10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00248-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clarke TA, Hemmings AM, Burlat B, Butt JN, Cole JA, Richardson DJ. Comparison of the structural and kinetic properties of the cytochrome c nitrite reductases from Escherichia coli, Wolinella succinogenes, Sulfurospirillum deleyianum and Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Biochem Soc Trans 2006; 34:143-145 10.1042/BST0340143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luijten MLGC, Weelink SAB, Godschalk B, Langenhoff AAM, Eekert MHA, Schraa G, Stams AJM. Anaerobic reduction and oxidation of quinone moieties and the reduction of oxidized metals by halorespiring and related organisms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2004; 49:145-150 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins MD, Widdel F. Respiratory quinones of sulphate-reducing and sulphur-reducing bacteria: a systematic investigation. Syst Appl Microbiol 1986; 8:8-18 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luijten MLGC, de Weert J, Smidt H, Boschker HTS, de Vos WM, Schraa G, Stams AJM. Description of Sulfurospirillum halorespirans sp. nov., an anaerobic, tetrachloroethene-respiring bacterium, and transfer of Dehalospirillum multivorans to the genus Sulfurospirillum as Sulfurospirillum multivorans comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:787-793 10.1099/ijs.0.02417-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.List of media used at DSMZ for cell growth: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/ media_list.php

- 31.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova N, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter JC, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]