Abstract

Brachyspira murdochii Stanton et al. 1992 is a non-pathogenic, host-associated spirochete of the family Brachyspiraceae. Initially isolated from the intestinal content of a healthy swine, the ‘group B spirochaetes’ were first described as Serpulina murdochii. Members of the family Brachyspiraceae are of great phylogenetic interest because of the extremely isolated location of this family within the phylum ‘Spirochaetes’. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. This is the first completed genome sequence of a type strain of a member of the family Brachyspiraceae and only the second genome sequence from a member of the genus Brachyspira. The 3,241,804 bp long genome with its 2,893 protein-coding and 40 RNA genes is a part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: host-associated, non-pathogenic, motile, anaerobic, Gram-negative, Brachyspiraceae, Spirochaetes, GEBA

Introduction

Strain 56-150T (= DSM 12563 = ATCC 51284 = CIP 105832) is the type strain of the species Brachyspira murdochii. This strain was first described as Serpulina murdochii [1,2], and later transferred to the genus Brachyspira [3]. The genus Brachyspira currently consists of seven species, with Brachyspira aalborgi as the type species [4,5]. The genus Brachyspira is the only genus in the not yet formally described family ‘Brachyspiraceae’ [6,7]. The generic name derives from ‘brachys’, Greek for short, and ‘spira’, Latin for a coil, a helix, to mean ‘a short helix’ [5]. The species name for B. murdochii derives from the city of Murdoch, in recognition of work conducted at Murdoch University in Western Australia, where the type strain was identified [1]. Some species of the genus Brachyspira cause swine dysentery and porcine intestinal spirochetosis. Swine dysentery is a severe, mucohemorrhagic disease that sometimes leads to death of the animals [1]. B. murdochii is generally not considered to be a pathogen, although occasionally it has been seen in association with colitis in pigs [3,8], and was also associated with clinical problems on certain farms [9-11].

In 1992, a user-friendly and robust novel PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the Brachyspira nox-gene was developed, which allows one to identify, with high specificity, members of B. murdochii using only two restriction endonucleases [12]. More recently, a multi-locus sequence typing scheme was developed that facilitates the identification of Brachyspira species and reveals the intraspecies diversity of B. murdochii [13] (see also http://pubmlst.org/brachyspira/).

Only one genome of a member of the family ‘Brachyspiraceae’ been sequenced to date: B. hyodysenteriae strain WA1 [14],. It is an intestinal pathogen of pigs. Based on 16S rRNA sequence this strain is 0.8% different from strain 56-150T. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for B. murdochii 56-150T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

Brachyspira species colonize the lower intestinal tract (cecum and colons) of animals and humans [6]. The type of B. murdochii, 56-150T, was isolated from a healthy swine in Canada [1,15]. Other isolates have been obtained from wild rats in Ohio, USA, from laboratory rats in Murdoch, Western Australia [16], and from the joint fluid of a lame pig [17]. Further isolates have been obtained from the feces or gastrointestinal tract of pigs in Canada, Tasmania, Queensland, and Western Australia [2,15]. The type strains of the other species of the genus Brachyspira share 95.9-99.4% 16S rRNA sequence identity with strain 56-150T. GenBank contains 16S rRNA sequences for about 250 Brachyspira isolates, all of which share at least 96% sequence identity with strain 56-150T [18]. The closest related type strain of a species outside of the Brachyspira, but within the order Spirochaetales, is Turneriella parva [19], which exhibits only 75% 16S rRNA sequence similarity [18]. 16S rRNA sequences from environmental samples and metagenomic surveys do not exceed 78-79% sequence similarity to strain 56-150T, with the sole exception of one clone from a metagenome analysis of human diarrhea [20], indicating that members of the species, genus and even family are poorly represented in the habitats outside of various animal intestines screened thus far (status March 2010).

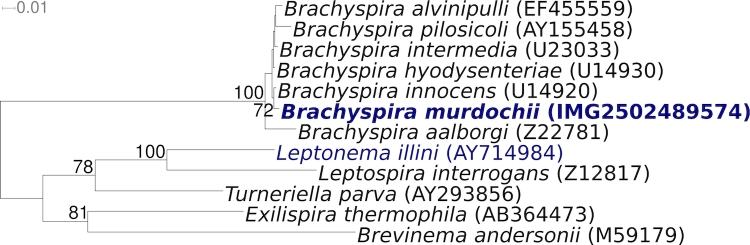

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of B. murdochii 56-150T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequence of the single 16S rRNA gene in the genome sequence is identical with the previously published 16S rRNA gene sequence generated from DSM 12563 (AY312492).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of B. murdochii 56-150T relative to the other type strains within the genus and to the type strains of the other genera within the class Spirochaetes (excluding members of the Spirochaetaceae). The tree was inferred from 1,396 aligned characters [21,22] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [23] and rooted in accordance with the current taxonomy. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates if [24] larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [25] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold.

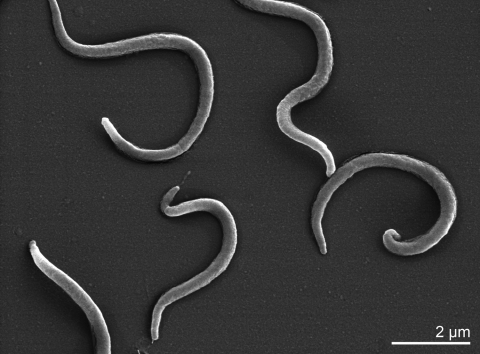

The cells of B. murdochii 56-l50T were 5 - 8 by 0.35 - 0.4 µm in size (Table 1 and Figure 2), and each cell possessed 22 to 26 flagella (11 to 13 inserted at each end) [1]. In brain/heart infusion broth containing 10% calf serum (BHIS) under an N2-O2 (99::l) atmosphere, strain 56-150T had optimum growth temperatures of 39 to 42°C (shortest population doubling times and highest final population densities) [1]. In BHIS broth at 39°C, the doubling times of strain 56-150T were 2 to 4 h, and the final population densities were 0.5 x l09 to 2.0 x l09 cells/ml. Strain 56-150T did not grow at 32 or 47°C [1].

Table 1. Classification and general features of B. murdochii 56-150T according to the MIGS recommendations [26].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [27] | |

| Phylum Spirochaetes | TAS [28] | ||

| Class Spirochaetes | TAS [28] | ||

| Order Spirochaetales | TAS [29,30] | ||

| Family Brachyspiraceae | TAS [31] | ||

| Genus Brachyspira | TAS [5] | ||

| Species Brachyspira murdochii | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain 56-150 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | helical cells with regular coiling pattern | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | motile (periplasmic flagella) | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | does not grow at 32°C or 47°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 39°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | unknown | TAS | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | anaerobic, aerotolerant | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | soluble sugars | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | chemoorganotrophic | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | animal intestinal tract | TAS [6] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | host-associated | TAS [32] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | no | TAS [33] |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [34] | |

| Isolation | swine | TAS [15] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Quebec, Canada | TAS [15] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1992 | TAS [15] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

52.939 -73.549 |

TAS [1] TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | TAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported | TAS |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [35]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of B. murdochii 56-150T

Substrates that support growth of strain 56-150T in HS broth (basal heart infusion broth containing 10% fetal calf serum) include glucose, fructose, sucrose, N-acetylglucosamine, pyruvate, L-fucose, cellobiose, trehalose, maltose, mannose, and lactose, but not galactose, D-fucose, glucosamine, ribose, raffinose, rhamnose, or xylose [1]. In HS broth supplemented with 0.4% glucose under an N2-O2 (99:l) atmosphere, the metabolic end products of strain 56-150T are acetate, butyrate, ethanol, CO2, and H2. Strain 56-150T produces more H2 than CO2 [1], which is indicative of NADH-ferredoxin oxidoreductase reaction [6]. The ethanol is likely to be formed from acetyl-CoA by the enzymes acetaldehyde dehydrogenase and alcohol dehydrogenase [6]. Strain 56-150T is weakly hemolytic, negative for indole production, does not hydrolyze hippurate, is negative for α-galactosidase and α-glucosidase activity, but positive for β-glucosidase activity [1]. Strain 56-150T is anaerobic but aerotolerant [1].

Minimal inhibitory concentrations have been determined for strain 56-150T for tiamulin hydrogen fumarate, tylosin tartrate, erythromycin, clindamycin hydrochloride, virginiamycin, and carbadox [36]. Several strains of B. murdochii have been described to be naturally resistant against the rifampicin [7,32]. Also, a ring test for quality assessment for diagnostics and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the genus Brachyspira has been reported [37].

Chemotaxonomy

At present there are no reports on the chemotaxonomy of B. murdochii. However, some data are available for B. innocens (formerly classified as Treponema innocens [6]), the species that is currently most closely related to B. murdochii [13]. B. innocens cellular phospholipids and glycolipids were found to contain acyl (fatty acids with ester linkage) with alkenyl (unsaturated alcohol with ether linkage) side chains [6,38]. The glycolipid of B. innocens contains monoglycosyldiglyceride (MGDG) and, in most strains, acylMGDG is also found, with galactose as the predominant sugar moiety [38].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [39], and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [40]. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [25] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Four genomic libraries: two Sanger 6kb and 8 kb pMCL200 library, one fosmid library, one 454 standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 GS FLX |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 19.7× Sanger; 48.9× pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 1.1.02.15, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001959 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | May 13, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01276 | |

| NCBI project ID | 29543 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2502422316 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 12563 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

B. murdochii, strain 56-150T, DSM 12563, was grown anaerobically in DSMZ medium 840 (Serpulina murdochii medium) [41] at 37°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with lysis modification st/L according to Wu et al. [40].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed can be found at the JGI website (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/). In total, 861,386 Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 3,554 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using the parallel phrap assembler (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible misassemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones [42]. A total of 300 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together, the combination of the Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms provided 68.6× coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 79,829 Sanger reads and 861,386 pyrosequencing reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [43] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [44]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGR-Fam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [45].

Genome properties

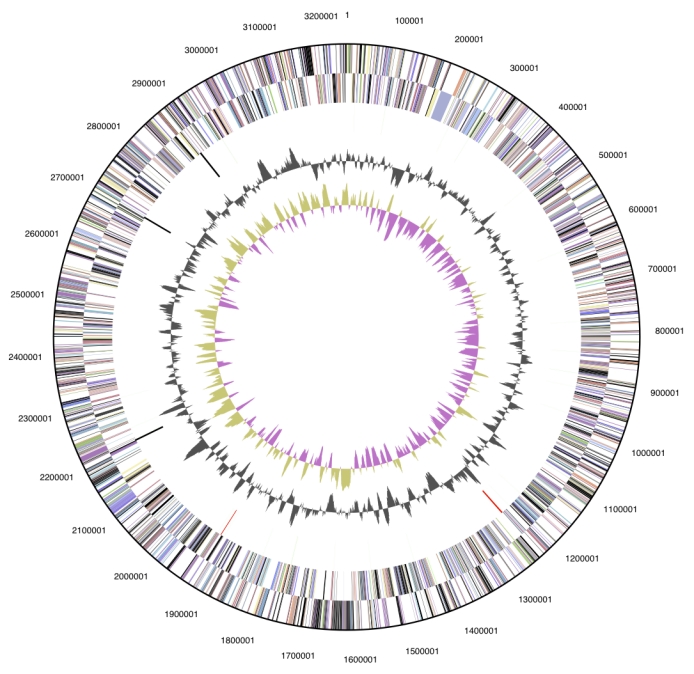

The genome is 3,241,804 bp long and comprises one main circular chromosome with an overall GC content of 27.8% (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 2,893 genes predicted, 2,853 were protein-coding genes, and 40 RNAs. A total of 44 pseudogenes were identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (66.2%) were assigned a putative function while those remaining were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,241,804 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,841,470 | 87.65% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 899,647 | 27.75% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 2,893 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 40 | 1.38% |

| rRNA operons | 1 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,893 | 98.62% |

| Pseudo genes | 44 | 1.52% |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,914 | 66.16% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 610 | 21.09% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,815 | 62.74% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 1,973 | 68.20% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 577 | 19.94% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 737 | 25.48% |

| CRISPR repeats | 2 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 134 | 6.6 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 81 | 4.0 | Transcription |

| L | 104 | 5.2 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 20 | 1.0 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 44 | 2.2 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 116 | 5.8 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 143 | 7.1 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 100 | 5.0 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 51 | 2.5 | Intracellular trafficking secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 62 | 3.1 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 111 | 5.5 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 143 | 7.1 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 185 | 9.2 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 56 | 2.8 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 67 | 3.3 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 53 | 2.6 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 99 | 4.9 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 20 | 1.0 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 286 | 14.2 | General function prediction only |

| S | 143 | 7.1 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,078 | 37.3 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Sabine Welnitz for growing B. murdochii cells and Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis (both at DSMZ). This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, UT-Battelle, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1 and SI 1352/1-2.

References

- 1.Stanton TB, Fournie-Amazouz E, Postic D, Trott DJ, Grimont PAD, Baranton G, Hampson DJ, Saint Girons I. Recognition of two new species of intestinal spirochetes: Serpulina intermedia sp. nov. and Serpulina murdochii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:1007-1012 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JI, Hampson DJ. Genetic characterisation of intestinal spirochaetes and their association with disease. J Med Microbiol 1994; 40:365-371 10.1099/00222615-40-5-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hampson DJ, La T. Reclassification of Serpulina intermedia and Serpulina murdochii in the genus Brachyspira as Brachyspira intermedia comb. nov. and Brachyspira murdochii comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1009-1012 10.1099/ijs.0.64004-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Euzéby JP. List of bacterial names with standing in nomenclature: A folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hovind-Hougen K, Birch-Andersen A, Henrik-Nielsen R, Orholm M, Pedersen JO, Teglbjaerg PS, Thaysen EH. Intestinal spirochetosis: morphological characterization and cultivation of the spirochete Brachyspira aalborgi gen. nov., sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol 1982; 16:1127-1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanton TB. 2006. The genus Brachyspira In M Dworkin, S Falkow, E Rosenberg, KH Schleifer E Stackebrandt (eds), The Prokaryotes, 3. ed, vol. 7. Springer, New York, p. 330-356. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE. Phylogenetic foundation of spirochetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 2000; 2:341-344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissenböck H, Maderner A, Herzog AM, Lussy H, Nowotny N. Amplification and sequencing of Brachyspira spp. specific portions of nox using paraffin-embedded tissue samples from clinical colitis in Austrian pigs shows frequent solitary presence of Brachyspira murdochii. Vet Microbiol 2005; 111:67-75 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephens CP, Hampson DJ. Prevalence and disease association of intestinal spirochaetes in chickens in eastern Australia. 1999; 28:447-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephens CP, Oxberry SL, Phillips ND, La T, Hampson DJ. The use of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis to characterise intestinal spirochaetes (Brachyspira spp.) colonising hens in commercial flocks. Vet Microbiol 2005; 107:149-157 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feberwee A, Hampson DJ, Phillips ND, La T, van der Heijden HMJF, Wellenberg GJ, Dwars RM, Landman WJM. Identification of Brachyspira hyodysenteriae and other pathogenic Brachyspira species in chickens from laying flocks with diarrhea or reduced production or both. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:593-600 10.1128/JCM.01829-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohde J, Rothkamp A, Gerlach GF. Differentiation of porcine Brachyspira species by a novel nox PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:2598-2600 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2598-2600.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Råsbäck T, Johansson KE, Jansson DS, Fellstrom C, Alikhani MY, La T, Dunn DS, Hampson DJ. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for intestinal spirochaetes within the genus Brachyspira. Microbiology 2007; 153:4074-4087 10.1099/mic.0.2007/008540-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellgard MI, Eanchanthuek P, La T, Ryan K, Moolhuijzen P, Albertyn Z, Shaban B, Motro Y, Dunn DS, Schibeci D, et al. Genome sequence of the pathogenic intestinal spirochaete Brachyspira hyodysenteriae reveals adapations to its lifestyle in the porcine large intestions. PLoS ONE 2009; 4:e4641 10.1371/journal.pone.0004641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JI, Hampson DJ, Lymbery AJ, Harders SJ. The porcine intestinal spirochaetes: identification of new genetic groups. Vet Microbiol 1993; 34:273-285 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90017-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trott DJ, Atyeo RF, Lee JI, Swayne DA, Stoutenbgurg JW, Hampson DJ. Genetic relatedness amongst intestinal spirochaetes isolated from rate and birds. Lett Appl Microbiol 1996; 23:431-436 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1996.tb01352.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampson DJ, Robertson ID, Oxberry SL. Isolation of Serpulina murdochii from the joint fluid of a lame pig. Aust Vet J 1999; 77:48 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1999.tb12430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chun J, Lee JH, Jung Y, Kim M, Kim S, Kim BK, Lim YW. EzTaxon: a web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:2259-2261 10.1099/ijs.0.64915-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levett PN, Morey RE, Galloway R, Steigerwalt AG, Ellis WA. Reclassification of Leptospira parva Hovind-Hougen et al. 1982 as Turneriella parva gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:1497-1499 10.1099/ijs.0.63088-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkbeiner SR, Allred AF, Tarr PI, Klenin EJ, Kirkwood CD, Wang D. Metagenomic analysis of human iarrhea: viral detection and discovery. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4:e1000011 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A Rapid Bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrity GM, Lilburn TG, Cole JR, Harrison SH, Euzéby J, Tindall BJ. Taxonomic outline of the Bacteria and Archaea, Release 7.7 March 6, 2007. Part 11 - The Bacteria: Phyla "Planctomycetes", "Chlamydiae", "Spirochaetes", "Fibrobacteres", "Acidobacteria", "Bacteroidetes", "Fusobacteria", "Verrucomicrobia", "Dictyoglomi", "Gemmatimonadetes", and "Lentisphaerae". http://www.taxonomicoutline.org/index.php/toba/article/viewFile/188/220 2007.

- 29.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of Bacteria. II. The primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol 1917; 2:155-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE. Phylogenetic foundation of spirochetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 2000; 2:341-344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imachi H, Sakai S, Hirayama H, Nakagawa S, Nunoura T, Takai K, Horikoshi K. Exilispira thermophila gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic, thermophilic spirochaete isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent chimney. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:2258-2265 10.1099/ijs.0.65727-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanton TB, Postic D, Jensen NS. Serpulina alvinipulli sp. nov., a new Serpulina species that is enteropathogenic for chickens. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1998; 48:669-676 10.1099/00207713-48-3-669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Classification of Bacteria and Archaea in risk groups. www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 35.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsson M, Fellstrom C, Gunnarsson A, Landen A, Franklin A. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of porcine brachyspira (Serpulina) species isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:2596-2604 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2596-2604.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Råsbäck T, Fellström C, Bergsjø B, Cizek A, Collin K, Gunnarsson A, Jensen SM, Mars A, Thomson J, Vyt P, et al. Assessment of diagnostics and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Brachyspira species using a ring test. Vet Microbiol 2005; 109:229-243 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews HM, Kinyon JM. Cellular lipid comparisons between strains of Treponema hyodysenteriae and Treponema innocens. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1984; 34:160-165 10.1099/00207713-34-2-160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klenk HP, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol (In press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 42.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter J, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods (Epub). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]