Abstract

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv trifolii is a soil-inhabiting bacterium that has the capacity to be an effective nitrogen fixing microsymbiont of a diverse range of annual Trifolium (clover) species. Strain WSM1325 is an aerobic, motile, non-spore forming, Gram-negative rod isolated from root nodules collected in 1993 from the Greek Island of Serifos. WSM1325 is produced commercially in Australia as an inoculant for a broad range of annual clovers of Mediterranean origin due to its superior attributes of saprophytic competence, nitrogen fixation and acid-tolerance. Here we describe the basic features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence, and annotation. This is the first completed genome sequence for a microsymbiont of annual clovers. We reveal that its genome size is 7,418,122 bp encoding 7,232 protein-coding genes and 61 RNA-only encoding genes. This multipartite genome contains 6 distinct replicons; a chromosome of size 4,767,043 bp and 5 plasmids of size 828,924 bp, 660,973 bp, 516,088 bp, 350,312 bp and 294,782 bp.

Keywords: microsymbiont, non-pathogenic, aerobic, Gram-negative rod, root-nodule bacteria, nitrogen fixation, Alphaproteobacteria

Introduction

The productivity of agricultural systems is heavily dependent on nitrogen (N) [1]. The requirement for N-input can be met by the application of exogenous N-fertilizer manufactured through the Haber-Bosch process, but as the cost of fossil fuel-derived energy increases, so does the cost to manufacture and apply such fertilizer. Furthermore, there are inherent issues with the synthesis and application of N-fertilizer, including greenhouse gas emissions and run-off causing eutrophication. Alternatively, N can be obtained from symbiotic nitrogen fixation (SNF) by root nodule bacteria (rhizobia) on nodulated legumes [2]; this is a key biological process in natural and agricultural environments driven by solar radiation and utilizing atmospheric CO2. The commonly accepted figure for global SNF in agriculture is 50-70 million metric tons annually, worth in excess of U.S. $10 billion [3]. Rhizobia are applied across 400 million ha of agricultural land per annum to improve legume forage and crop production through symbiotic N-fixation [3].

The clover (Trifolium) nodulating Rhizobium R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii is amongst the most exploited species of root-nodule bacteria in world agriculture. Clovers are widely grown pasture legumes and include both annual species (e.g. T. subterraneum) and perennial species (e.g. T. pratense, T. repens and T. polymorphum). Clovers are adapted to a wide range of environments, from sub-tropical to moist Mediterranean systems, and thus are important nitrogen-fixing legumes in many natural and agricultural regions of North and South America, Europe, Africa and Australasia [4].

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM1325 was isolated from a nodule recovered from the roots of an annual clover plant growing near Livadi beach on the Greek Cyclades island of Serifos in 1993 [5]. Strain WSM1325 is of particular interest because it is a highly effective nitrogen-fixing microsymbiont of a broad range of annual clovers of Mediterranean origin [5] and is also saprophytically competent in acid, infertile soils of both Uruguay and southern Australia [6]. Strain WSM1325 is an effective microsymbiont under competitive conditions for nodulation in what appears to be a host-mediated selection process [7].

As well as being a highly effective inoculant strain for annual Trifolium spp., strain WSM1325 is compatible with key perennial clovers of Mediterranean origin used in farming, such as T. repens and T. fragiferum, and is therefore one of the most important clover inoculants used in agriculture. However, WSM1325 is incompatible with American and African clovers, sometimes nodulating but never fixing N [5]. This is in contrast to other Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strains, such as WSM2304, which are effective at N-fixation with some perennial American clovers, but ineffective with the Mediterranean clovers [5-7].

Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM1325 (Table 1), together with the description of a complete genome sequence and annotation.

Table 1. Classification and general features of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 according to the MIGS recommendations [8].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [9] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [10,11] | ||

| Class Alphaproteobacteria | TAS [12,13] | ||

| Order Rhizobiales | TAS [13,14] | ||

| Family Rhizobiaceae | TAS [15,16] | ||

| Genus Rhizobium | TAS [17-19] | ||

| Species Rhizobium leguminosarum | TAS [18,20] | ||

| Biovar trifolii Strain WSM1325 | |||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [17] | |

| Cell shape | rod | TAS [17] | |

| Motility | motile | TAS [17] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [17] | |

| Temperature range | mesophile | TAS [17] | |

| Optimum temperature | 28°C | TAS [17] | |

| Salinity | unknown | TAS [17] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | aerobic | TAS [17] |

| Carbon source | glucose, mannitol, glutamate | TAS [5-7] | |

| Energy source | chemoorganotroph | ||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Soil, root nodule, host | TAS [5-7] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living, Symbiotic | TAS [5-7] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS [17] |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [21] | |

| Isolation | Root nodule | TAS [22] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Livadi beach, Serifos, Cyclades, Greece |

TAS [22] |

| MIGS-5 | Nodule collection date | April 1993 | TAS [22] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Longitude Latitude |

24.518901 37.147034 |

TAS [22] |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 2m | TAS [22] |

Evidence codes - TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from http://www.geneontology.org/GO.evidence.shtml of the Gene Ontology project [23]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Classification and features

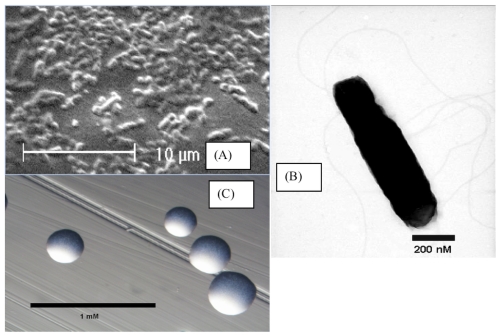

R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 is a motile, Gram-negative, non-spore-forming rod (Figure 1A,B) in the Rhizobiaceae family of the class Alphaproteobacteria that forms mucoid colonies (Figure 1C) on solid media [24]. It has a mean generation time of 3.9 h in rich medium at the optimal growth temperature of 28°C [7].

Figure 1.

Images of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM1325 using scanning (A) and transmission (B) electron microscopy and the appearance of colony morphology on solid media (C).

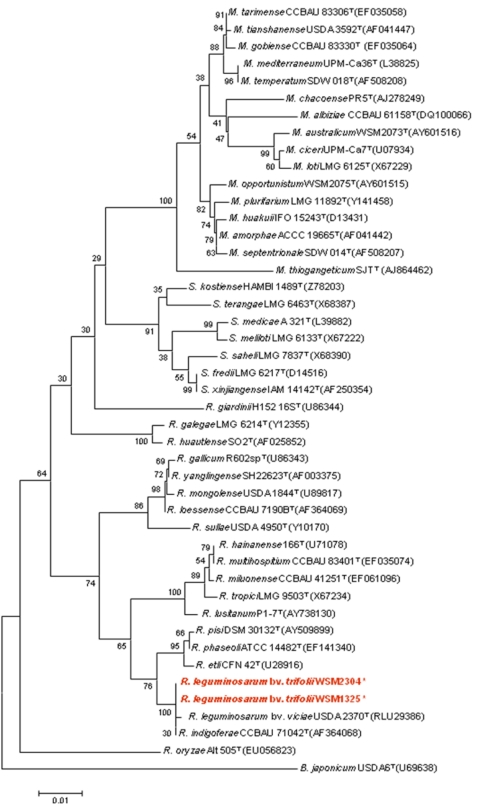

Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM1325 in a 16S rRNA-based tree. An intragenic fragment of 1,440 bp was chosen since the 16S rRNA gene has not been completely sequenced in many type strains. A comparison of the entire 16S rRNA gene of WSM1325 to completely sequenced 16S rRNA genes of other rhizobia revealed 100% gene sequence identity to the same gene of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2304 but revealed a 1 bp difference to the same gene of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strain 3841.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of R. leguminosarum bv trifolii strain WSM1325 with the type strains of Rhizobiaceae based on aligned sequences of the 16S rRNA gene (1,440 bp internal region). All sites were informative and there were no gap-containing sites. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA, version 3.1 [25]. Kimura two-parameter distances were derived from the aligned sequences [26] and a bootstrap analysis [27] as performed with 500 replicates in order to construct a consensus unrooted tree using the neighbor-joining method [28] for each gene alignment separately. B.-Bradyrhizobium; M.-Mesorhizobium; R.-Rhizobium; S-Ensifer (Sinorhizobium). Type strains are indicated with a superscript T. Strains with a genome sequencing project registered in GOLD [22] are in bold red print. Published genomes are designated with an asterisk.

Symbiotaxonomy

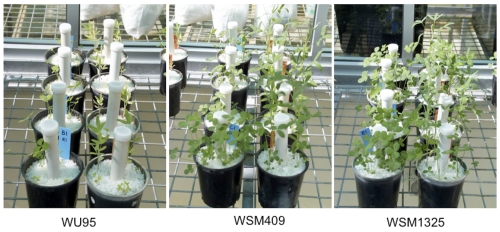

R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 nodulates (Nod+) and fixes nitrogen effectively (Fix+) with a wide range of annual clovers of Mediterranean origin which are in commercial agriculture, globally. Examples of these clover species include T. subterraneum, T. vesiculosum, T. purpureum T. glanduliferum, T. resupinatum, T. michellianum and T. incarnatum. An illustration of the ability of WSM1325 to fix nitrogen effectively across a range of annual clover species is displayed in Figure 3. Additionally, WSM1325 is Fix+ with some Mediterranean perennial clovers such as T. repens and T. fragiferum, but is inconsistently Nod+, and consistently Fix- with clovers of African and American origin [5,30]. Under conditions of competitive nodulation, WSM1325 may preferentially nodulate T. purpureum even when outnumbered 100:1 by WSM2304 [7].

Figure 3.

An illustration of the N-fixing capacity of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 with four annual Trifolium spp. (T. vesiculosum, T. dasyurum (pots with orange tags), T. isthmocarpum and T. spumosum (pots with blue tags) in four replicates, front to back), compared with superseded Australian inoculants; far left WU95 (1968 to 1994), middle WSM409 (1994 to 2004) and right, WSM1325 (Australian commercial inoculant strain 2004 to present [29]).

Genome sequencing and annotation information

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its environmental and agricultural relevance to issues in global carbon cycling, alternative energy production, and biogeochemical importance, and is part of the Community Sequencing Program at the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (JGI) for projects of relevance to agency missions. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [22] and the complete genome sequence in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information for R. leguminosarum bv trifolii WSM1325.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Four genomic libraries: three Sanger libraries - 2 kb pTH1522, 8 kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos and one 454 pyrosequence standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730xl, 454 GS FLX |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 16× Sanger; 20× pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 1.1.02.15, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| Genbank ID | CP001622 (Chomosome) a CP001623 (pR132501) b CP001624 (pR132502) c CP001625 (pR132503) d CP001626 (pR132504) e CP001627 (pR132505) f |

|

| Genbank Date of Release | May 7, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01039 g | |

| NCBI project ID | 20097 | |

| Database: IMG | 641736174 (draft) h | |

| Project relevance | Symbiotic nitrogen fixation, agriculture |

a http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/240856645; b http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/240861211

c http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/240861949; d http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/240862574

e http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/240863069; fhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/240863376

g http://genomesonline.org/GOLD_CARDS/Gc01039.html

h http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/pub/main.cgi?section=TaxonDetail&page=taxonDetail&taxon_oid=641736174

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 was grown to mid logarithmic phase in TY medium (a rich medium) [31] on a gyratory shaker at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 60 mL of cells using a CTAB (Cetyl trimethylammonium bromide) bacterial genomic DNA isolation method (http://my.jgi.doe.gov/general/index.html).

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at http://www.jgi.doe.gov/. 454 Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler, version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 6,084 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and to adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using the parallel phrap assembler (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones [32]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 2,155 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. Together, all sequence types provided 36× coverage of the genome. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [33] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePrimp pipeline [34]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analyses and functional annotation were performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG-ER) platform (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/er) [35].

Genome properties

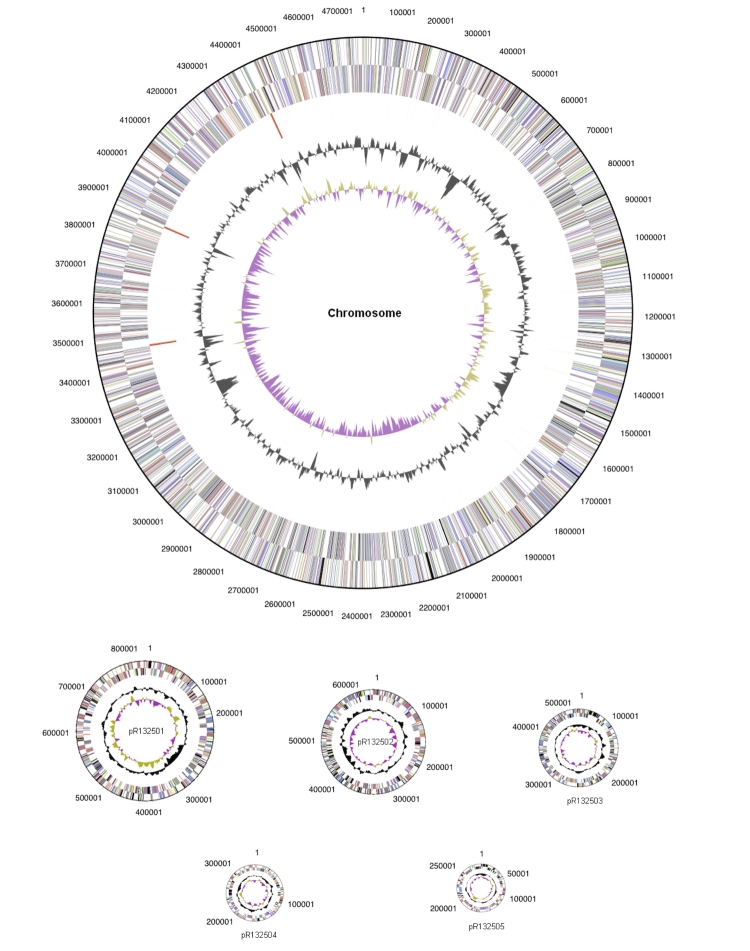

The genome is 7,418,122 bp long with a 60.77% GC content (Table 3) and comprised of 6 replicons; one circular chromosome of size 4,767,043 bp and five circular plasmids of size 828,924 bp, 660,973 bp, 516,088 bp, 350,312 bp and 294,782 bp (Figure 4). Of the 7293 genes predicted, 7,232 were protein coding genes, and 61 RNA only encoding genes. Two hundred and thirty one pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of genes (74.21%) were assigned a putative function whilst the remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics for R. leguminosarum bv trifolii WSM1325.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 7,418,122 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 6,485,014 | 87.42 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 4,507,991 | 60.77 |

| Number of replicons | 6 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 5 | |

| Total genes | 7,293 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 61 | 0.84 |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 7,232 | 99.16 |

| Pseudo genes | 231 | 3.17 |

| Genes with function prediction | 5,412 | 74.21 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 1,947 | 26.70 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 5,453 | 74.77 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 5,497 | 75.37 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,554 | 21.31 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,629 | 22.34 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

Figure 4.

Graphical circular maps of the chromosome and plasmids of R. leguminosarum bv trifolii WSM1325. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories as denoted by the IMG platform), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, sRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew. Chromosome and plasmids are not drawn to scale.

Table 4. The number of predicted protein-coding genes of R. leguminosarum bv trifolii WSM1325 associated with the 21 general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | % age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 195 | 2.70 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.01 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 610 | 8.43 | Transcription |

| L | 180 | 2.49 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.03 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 35 | 0.48 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 69 | 0.95 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 358 | 4.95 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 323 | 4.47 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 89 | 1.23 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.01 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.00 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 83 | 1.15 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 191 | 2.64 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 316 | 4.37 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 688 | 9.51 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 644 | 8.90 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 108 | 1.49 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 190 | 2.63 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 227 | 3.14 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 322 | 4.45 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 160 | 2.21 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 777 | 10.74 | General function prediction only |

| S | 586 | 8.10 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,779 | 24.60 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396. We thank Gordon Thompson (Murdoch University) for the preparation of SEM and TEM photos. We gratefully acknowledge the funding received from Murdoch University Strategic Research Fund through the Crop and Plant Research Institute (CaPRI), and the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC), to support the National Rhizobium Program (NRP) and the Centre for Rhizobium Studies (CRS) at Murdoch University.

References

- 1.Peoples MB, Hauggaard-Nielsen H, Jensen ES. Chapter 13. The potential environmental benefits and risks derived from legumes in rotations. In: Emerich, DW & Krishnan HB (Eds.), Agronomy Monograph 52. Nitrogen Fixation in Crop Production Am Soc Agron, Crop Sci Soc Am & Soil Sci Soc Am 2009, pp. 349-385 Madison, Wisconsin, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sprent JI. Legume nodulation: a global perspective. 2009. Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herridge DF, Peoples MB, Boddey RM. Global inputs of biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Marschner Review. Plant Soil 2008; 311:1-18 10.1007/s11104-008-9668-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zohary M, Heller D. The Genus Trifolium The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Ahva Printing Press 1984, Jerusalem. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howieson JG, Yates RJ, O'Hara GW, Ryder M, Real D. The interactions of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii in nodulation of annual and perennial Trifolium spp from diverse centres of origin. Aust J Exp Agric 2005; 45:199-207 10.1071/EA03167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yates RJ, Howieson JG, Real D, Reeve WG, Vivas-Marfisi A, O'Hara GW. Evidence of selection for effective nodulation in the Trifolium spp. symbiosis with Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii. Aust J Exp Agric 2005; 45:189-198 10.1071/EA03168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yates RJ, Howieson JG, Reeve WG, Brau L, Speijers J, Nandasena K, Real D, Sezmis E, O'Hara GW. Host-strain mediated selection for an effective nitrogen-fixing symbiosis between Trifolium spp. and Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii. Soil Biol Biochem 2008; 40:822-833 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV. Towards a richer description of our complete collection of genomes and metagenomes: the “Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence” (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. [2112744] Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Editor L. Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. List no. 106. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:2235-2238; . 10.1099/ijs.0.64108-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class I. Alphaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Editor L. Validation List No. 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuykendall LD. Order VI. Rhizobiales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 324. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuykendall LD. Order VI. Rhizobiales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 324. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conn HJ. Taxonomic relationships of certain non-sporeforming rods in soil. J Bacteriol 1938; 26:320-321 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuykendall LD, Hashem F, Wang ET. Genus VII. Rhizobium, 2005, pp 325-340. In: Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Second Edition. Volume 2 The Proteobacteria Part C The Alpha-, Delta-, and Epsilonproteobacteria Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (Eds.), Garrity GM (Editor in Chief) Springer Science and Business Media Inc, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan DC, Allen ON. Genus I. Rhizobium Frank 1889, 338; Nom. gen. cons. Opin. 34, Jud. Comm. 1970, 11. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Eighth Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1974, p. 262-264. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dangeard PA. Recherches sur les tubercles radicaux des Légumineuses. Botaniste, Paris 1926; 16:1-275 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biological Agents. Technical rules for biological agents www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 22.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howieson JG, Ewing MA, D'Antuono MF. Selection for acid tolerance in Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Soil 1988; 105:179-188 10.1007/BF02376781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 2004; 5:150-163 10.1093/bib/5.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura M. A simple model for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 1980; 16:111-120 10.1007/BF01731581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985; 39:783-791 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitou N, Nei M. Reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 1987; 4:406-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bullard GK, Roughley RJ, Pulsford DJ. The legume inoculant industry and inoculant quality control in Australia: 1953–2003. Aust J Exp Agric 2005; 45:127-140 10.1071/EA03159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centre for Rhizobium Studies. Annual Report. 2001. JG Howieson (Ed). Murdoch University Print, Perth, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reeve WG, Tiwari RP, Worsely PS, Dilworth MJ, Glenn AR, Howieson JG. Constructs for insertional mutagenesis, transcriptional signal localisation and gene regulation studies in root nodule and other bacteria. Microbiology 1999; 145:1307-1316 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter JC, Han C, Lapidus A , Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (strain 541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal/

- 34.http://geneprimp.jgi-psf.org/

- 35.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: A system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]