Abstract

The overall survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains poor due to both intrinsic and acquired chemotherapy resistance. Over expression of ATP binding cassette (ABC) proteins in AML cells has been suggested as a putative mechanism of drug resistance. Genetic variation among individuals affecting the expression or function of these proteins may contribute to inter-individual variation in treatment outcomes. DNA from pre-treatment bone marrow or blood samples from 261 patients age 20-85 years, who received cytarabine and anthracycline-based therapy at Roswell Park Cancer Institute between 1994 and 2006, was genotyped for eight non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in the ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2 drug transporter genes. Heterozygous (AG) or homozygous (AA) variant genotypes for rs2231137 (G34A) in the ABCG2 (BRCP) gene, compared to the wild type (GG) genotype were associated with both significantly improved survival (HR=0.44, 95%CI=0.25-0.79), and increased odds for toxicity (OR=8.41, 95%CI= 1.10-64.28). Thus genetic polymorphisms in the ABCG2 (BRCP) gene may contribute to differential survival outcomes and toxicities in AML patients via a mechanism of decreased drug efflux in both, AML cells and normal progenitors.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, multidrug resistance, polymorphisms, survival, toxicity

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clinically and biologically heterogeneous malignancy resulting from clonal proliferation of hematopoietic precursor cells ('blasts') which fail to differentiate, giving rise to hematopoietic insufficiency (granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia) [1–2]. Prognosis remains poor, with many patients dying due to intrinsic drug resistance of AML cells or relapse resulting from acquired resistance to initial therapy. Over expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transmembrane proteins, e.g. P-glycoprotein, which are involved in active transport of nutrients, biologically active substances and chemotherapeutic drugs across the plasma membrane [3–4] have been associated with inferior treatment outcome in AML [3, 5–7]. Genetic polymorphisms in ABC genes, which affect the level of expression or function of these transporter proteins, might thus be associated with increased toxicity and better survival in AML patients, due to decreased efflux from both somatic cells and AML cells, or decreased toxicity but poor survival, due to increased efflux from both somatic cells and AML cells,. In this study, we evaluated whether eight non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in three ABC genes: ABCC1, ABCB1 and ABCG2, located on chromosomes 16, 7 and 4 respectively, were associated with overall survival (OS) and toxicity in a cohort of 261 AML patients treated with Cytara-bine and Anthracycline-based therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients and clinical information

Patients between the ages of 20 and 85 years who were newly diagnosed with AML and received treatment at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI), Buffalo, New York, between 1994 and 2006, were included in the study sample. Morphologically confirmed cases of previously untreated primary or secondary AML, other than acute promyelocytic leukemia, by the French-American-British (FAB) criteria [8] were included in the sample. These patients received induction chemotherapy with either a standard-or high-dose regimen of cytarabine (ara-C) or an anthracycline. Two hundred and ninety three (N=293) patients met the eligibility criteria. Patients with missing genotype (n=31) or survival status (n=1) were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 261 patients.

Clinical information was obtained from the RPCI Leukemia Section Database which includes information on demographic and pre-treatment characteristics, treatment type and outcome, disease-free survival and overall survival. For information not included in the database or for missing data, information was abstracted from patients' medical records. Cytogenetic studies were performed in the RPCI Clinical Cytogenetics Laboratory and karyotypes were assigned to risk categories (favorable, intermediate, unfavorable) as described previously [9]. The study was approved by the RPCI Institutional Review Board.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Bone marrow (n=217) and blood samples (n=44) were transferred to green topped tubes containing heparin and then transported to the RPCI Tissue Procurement Laboratory. Mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation, washed twice, counted, re-suspended at a density of 1-2 × 107/ml in fetal calf serum with 20% dimethylsulfoxide, aliquoted into cryovials and cryopreserved at 120° C. DNA was then extracted using Gentra PureGene DNA extraction kits (Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Genotyping was determined using Sequenom's high-throughput matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry[10]. Functional non-synonymous SNPs were selected including rs1045642 (C3435T), rs2032582( G2677T), rs1128503 ( C1236T), rs2231142(C421A), rs2231137 (G34A), rs246221(T825C), rs2230671(G4002) and rs35587(T1062C).

Initially, a locus-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction was carried out, followed by an allele-specific primer extension reaction. PCR amplification was performed using SNP-specific primers. Controls for genotype and two-non template controls were included on each plate, as well as 10% duplicate samples. The PCR condition was 94° C for 15 minutes for hot start, followed by denaturing at 94° C for 20 seconds, annealing at 56° C for 30 seconds, extension at 72° C for 1 minute for 45 cycles, and final incubation at 72° Cfor3 minutes.

Statistical analysis

OS was measured from the date of diagnosis until death from any cause, with observation censored on the date the patient was last known to be alive or at the time of allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (n=38). Treatment response was evaluated according to National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored workshop guidelines (http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm). Complete remission (CR) was defined by ≤ 5% blasts in the marrow, normal peripheral blood cell counts including absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1,000/μL and platelet count ≥ 100,000/μL. Relapse was defined as a reappearance of leukemic blasts in the peripheral blood or ≥ 5% blasts in the bone marrow not attributable to any other cause. Severity of tox-icities was graded 1 (mild) through 5 (fatal) according to the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0. Toxicities of induction chemotherapy were combined into the following categories: genitourinary, gastrointestinal, hepatic, pulmonary, cardiovascular, hemorrhage, dermatologic, neurologic and metabolic. The grade of toxicity assigned to an organ group was the maximum grade of all the specific toxicities within that group.

Distributions of patient and disease characteristics were compared among genotypes using Chi-square analysis, Fisher's exact tests, ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis or Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate. Distribution of OS was estimated by Kaplan-Meier methods and compared between genotypes by log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of OS was performed to evaluate survival difference between genotype groups after adjusting for significant prognostic factors. Logistic regression models were used to examine treatment response and toxicity outcomes.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the 262 patients with AML are shown in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 65 years. The majority of the patients was Caucasian (86%) and had de novo onset of AML (75%), while 25% had secondary AML defined as preceded by an antecedent hematologic disorder or therapy-related. Statistically significant predictors of OS, resistant disease and complete response included age, cytogenetics, AML onset, type of induction (standard- vs. high-dose ara-C) and white blood cell (WBC) count at diagnosis (results not shown).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of 261 AML patients

| Variable | N (%)/mean(STD) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (STD) | 61.5 (15.70) |

| WBC | |

| <100,000 | 224(86) |

| >=100,000 | 37 (14) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 135(52) |

| Female | 126(48) |

| Complete response | |

| No | 123(47) |

| Yes | 138 (53) |

| Relapse | |

| No | 170(65) |

| Yes | 91 (35) |

| Race | |

| Whites | 233 (89) |

| Other | 28 (11) |

| FAB classification | |

| Acute unclassifiable leukemia (AUL) | 1 (0) |

| M0 | 13 (5) |

| M1 | 61 (23) |

| M2 | 112 (43) |

| M4 | 37 (14) |

| M4e | 7 (3) |

| M5a | 8 (3) |

| M5b | 4 (1) |

| M6 | 9 (3) |

| M7 | 2 (1) |

| UNK | 3 (1) |

| WHO | 3 (1) |

| Biphenotypic AML | 1 (0) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| Favorable | 19 (7) |

| Intermediate | 131 (50) |

| Unfavorable | 111 (43) |

| AML onset | |

| De novo | 195 (75) |

| Secondary | 66 (25) |

| Survival status | |

| Alive | 66 (23) |

| Dead | 145 (77) |

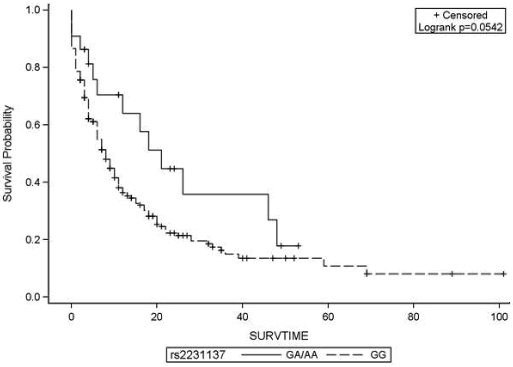

Table 2 displays the association of polymorphisms in eight ABC transporters and overall survival. Presence of one copy of the variant allele of ABCG2 (rs2231137/G34A) was associated with significantly reduced hazard of death (HR=0.44, 95%CI=0.25-0.79) compared to the homozygous wild type genotype (GG). The Kaplan-Meier survival probabilities for the AA/AG group are shown in Figure 1. While the homozygous AA genotype of rs2231142 was associated with more than four-fold increased hazard of death compared to homozygous CC genotype (HR=4.61, 95%CI=1.44-14.8), after adjusting for age, cytogenetics and AML onset, the hazard ratio was attenuated and was not statistically significant (HR=2.57, 95%CI=0.79-8.42).

Table 2.

Association of genetic polymorphisms in ATP binding cassette proteins and overall survival in 261 AML patients at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY

| Gene | SNP | Total | Events | Unadjusted HR | Age Adjusted HR | *Final adjusted model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N(%) | (95%CI) | (95%CI) | HR(95%CI) | ||

| ABCB1 | rs1045642 | |||||

| CC | 79 | 53(29.44) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| CT | 116 | 83(46.11) | 1.04(0.74-1.48) | 0.98(0.69-1.38) | 1.04(0.73-1.47) | |

| TT | 66 | 44(24.44) | 0.92(0.61-1.37) | 0.94(0.63-1.40) | 0.90(0.60-1.35) | |

| rs2032582 | ||||||

| GG | 104 | 72(40.00) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| G/T | 119 | 84(46.67) | 0.93(0.68-1.28) | 0.88(0.64-1.21) | 0.89(0.65-1.23) | |

| TT | 38 | 24(13.33) | 0.96(0.60-1.51) | 1.09(0.69-1.75) | 1.06(0.66-1.70) | |

| rs1128503 | ||||||

| CC | 95 | 69(38.33) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| TC | 127 | 85(47.22) | 0.77(0.56-1.06) | 0.76(0.55-1.04) | 0.82(0.59-1.13) | |

| TT | 39 | 26(14.44) | 0.86(0.55-1.36) | 1.09(0.69-1.72) | 1.05(0.66-1.67) | |

| ABCG2 | rs2231142 | |||||

| CC | 205 | 142(78.89) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| CA | 53 | 35(19.44) | 0.85(0.59-1.23) | 0.83(0.57-1.20) | 0.88(0.61-1.28) | |

| AA | 3 | 3(1.67) | 4.47(1.39-14.38) | 3.00(0.93-9.68) | 2.52(0.77-8.26) | |

| CA+AA | 56 | 38(21.11) | 4.61(1.44-14.80) | 3.11(0.97- | 2.57(0.79-8.42) | |

| rs2231137 | ||||||

| GG | 239 | 167(92.78) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AA+AG | 22 | 13(7.22) | 0.57(0.33-1.01) | 0.52(0.29-0.92) | 0.44(0.25-0.79) | |

| ABCC1 | rs246221 | |||||

| TT | 124 | 82(45.56) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| TC | 109 | 78(43.33) | 1.09(0.80-1.49) | 1.09(0.80-1.49) | 1.08(0.79-1.47) | |

| CC | 28 | 20(11.11) | 1.39(0.85-2.27) | 1.35(0.83-2.21) | 1.44(0.87-2.39) | |

| rs35587 | ||||||

| TT | 126 | 83(46.11) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| TC | 108 | 78(43.33) | 1.13(0.82-1.54) | 1.11(0.81-1.51) | 1.07(0.78-1.46) | |

| CC | 27 | 19(10.56) | 1.36(0.83-2.25) | 1.33(0.81-2.19) | 1.39(0.83-2.33) | |

| rs2230671 | ||||||

| GG | 152 | 111(61.67) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| GA | 94 | 56(31.11) | 0.73(0.53-1.01) | 0.75(0.54-1.04) | 0.79(0.57-1.09) | |

| +AA | 15 | 13(7.22) | 1.02(0.57-1.82) | 0.93(0.52-1.66) | 0.87(0.49-1.55) | |

| GA+AA | 109 | 69(38.33) | 0.77(0.57-1.04) | 0.78(0.58-1.05) | 0.80(0.59-1.09) |

adjusted for age, cytogenetic and AML onset

Abbreviations: MDR1=multi drug resistance gene 1,BCRP=breast cancer resistance protein, HR=hazard's ratio, CI=confidence interval

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival probabilities of 261 AML patients with single nucleotide polymorphism in ABCG2 gene (rs2231137). G and A refer to wild type and variant alleles, respectively. SURVTIME=survival time in months.

We did not find any significant associations between polymorphisms in ABCB1 and ABCC1 and OS, either when we considered the AML population in its entirety or when restricted to patients who self-reported as Caucasian.

To test the hypothesis that SNPs associated with OS would also be associated with toxicity we analyzed the association of the rs2231137 (G34A) SNPs in the ABCG2 gene that was found to reduce the hazard of death. We found a significantly increased odds of toxicity associated with one copy of the variant allele in rs2231137 (G34A) when compared to wild type GG genotype (OR=8.41, 95%CI=1.10-64.28) after adjusting for confounders (results not shown).

Discussion

A large proportion of AML patients receiving chemotherapy has resistant disease or relapse following initial response due to drug resistance [11], which may be present intrinsically at diagnosis or develop secondarily [3, 11]. Identification of genetic variants associated with multidrug resistance is an important guide for tailoring chemotherapy to both improve treatment response and attenuate drug toxicity. Increased expression of ABC proteins is one of the several mechanisms of drug resistance [3] and we therefore investigated multi-drug resistance (MDR) genes including ABCG2, ABCC1 and ABCB1.

Increased expression of ABCG2 (BCRP) has been found to be associated with drug resistance in cell lines such as MCF7 [12]. ABCG2 is a half-transporter and requires dimerization or oligomerization to form an active transporter [13]. Higher levels of ABCG2 mRNA have been shown to be associated with increased incidence of refractory or relapsed AML, indicating the functional role of ABCG2 in AML survival outcome [12]. We found a significantly reduced hazard of death in patients with GA/AA genotype compared to those with GG genotype for the SNP rs2231137 (G34A; HR=0.44, 95% CI=0.25-0.79). The variant allele was associated with a favorable survival outcome. The rs2231137 (G34A) polymorphism results in valine to methionine substitution (V12M) in the amino acid sequence of the protein and findings across studies have been contradictory regarding its functional significance. For example, in a study using LLC-KP1 cells transfected with variant vectors, no significant difference in the levels of protein expression or transport activity of ABCG2 protein between wild type and G34A variant cell types was observed [14]. However it should be noted that protein expression is influenced by factors such as chromatin changes, methylation and acetylation [15] which might be difficult to evaluate in the controlled setting of an in vitro study. In another study, ABCG2 mRNA expression was found to be significantly lower in liver tissue of Hispanics who carried the G34A variant genotype [16] potentially owing to alternative splicing of mRNA in G34A variant individuals compared to that in individuals with wild genotype [16]. While it is interesting to note that our findings are in line with the toxicity effects that would be expected if this polymorphism is functional and is actually associated with improved survival, it is important that the functional significance of rs2231137(G34A) be fully evaluated and that its clinical significance be evaluated in additional appropriately sized populations.

We found a significantly increased risk of grade 3 or more toxicity in patients with AA/AG genotypes for the SNP rs2231137(G34A) compared to GG homozygotes. Thus higher survival probability is associated with greater toxicity. Conversely, AML patients who do not have the mutant ABCG2 genotype, at rs2231137(G34A), have lower survival rates and lower risk of toxicity. ABCG2 protein expressed in normal tissues of AML patients may reduce hematological and gastrointestinal toxicity associated with chemotherapy [15] while that expressed in leukemic stem cells may be associated with drug resistance.

While Imai et al found that rs2231142 (C421A) polymorphism in the ABCG2 gene was associated with decreased protein expression and lower levels of drug resistance compared to wild type, the mRNA expression associated with both variants was the same; which might be suggestive of post-transcriptional modification in mRNA [15]. Decreased protein expression associated with variant alleles should correlate with improved survival outcome. However, we found more than two-fold increased hazard of death in patients with CA/AA variant genotype compared to wild GG genotype of rs2231142(C421A), although not statistically significant. Imai et al included a Japanese population, while our study includes predominantly Caucasians. Allele frequencies vary greatly between different ethnic groups [17] perhaps indicating differing patterns of evolutionary pressure. Clearly further research is required to elucidate the effect of polymorphism in rs2231142 (C421A) on the levels of mRNA and protein expression levels in AML patients.

The study has some limitations. The external validity of our findings is limited to predominantly Caucasian patients. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons. However, since genes analyzed in this study have been identified to be involved in drug transport, our hypothesis had a strong biological basis and hence multiple comparison bias would not be a major issue in this study.

The analyses of both survival and toxicity in a well characterized cohort in this study were appropriately powered to detect pharmacogenetic effects. Significant effect of polymorphism in ABCG2 gene on survival as well as drug toxicity in AML patients is an interesting finding that might lead to screening high-risk patients in order to plan chemotherapy. Larger studies are required to further elucidate this association.

References

- 1.Ferrara F. Unanswered questions in acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:443–450. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estey E, Dohner H, Estey E, Dohner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2006;368:1894–1907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jonge-Peeters SD, Kuipers F, de Vries EG, Vellenga E. ABC transporter expression in hema-topoietic stem cells and the role in AML drug resistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinbach D, Legrand O. ABC transporters and drug resistance in leukemia: was P-gp nothing but the first head of the Hydra? Leukemia. 1172;21:1172–1176. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samdani A, Vijapurkar U, Grimm MA, Spier CS, Grogan TM, Glinsmann-Gibson BJ, List AF. Cytogenetics and P-glycoprotein (PGP) are independent predictors of treatment outcome in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Leukemia Res. 1996;20:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leith CP, Kopecky KJ, Chen IM, Eijdems L, Slovak ML, McConnell TS, Head DR, Weick J, Grever MR, Appelbaum FR, Willman CL. Frequency and clinical significance of the expression of the multidrug resistance proteins MDR1/P-glycoprotein, MRP1, and LRP in acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. Blood. 1999;94:1086–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, Sultan C. Proposed revised criteria for the classification of acute myeloid leukemia. A report of the French-American-British Cooperative Group. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:620–625. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK, Carroll AJ, Edwards CG, Arthur DC, Pettenati MJ, Patil SR, Rao KW, Watson MS, Koduru PR, Moore JO, Stone RM, Mayer RJ, Feldman EJ, Davey FR, Schiffer CA, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD Cancer Leukemia Group B. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100:4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang K, Fu DJ, Julien D, Braun A, Cantor CR, Koster H. Chip-based genotyping by mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10016–10020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Kolk DM, de Vries EG, van Putten WJ, Verdonck LF, Ossenkoppele GJ, Verhoef GE, Vellenga E. P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein activities in relation to treatment outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3205–3214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Wiemer EA, Prins A, Meijerink JP, Vossebeld PJ, van der Holt B, Pieters R, Sonneveld P. Increased expression of the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Leukemia. 2002;16:833–839. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ejendal KF, Hrycyna CA. Multidrug resistance and cancer: the role of the human ABC transporter ABCG2. Curr Protein Peptide Sci. 2002;3:503–511. doi: 10.2174/1389203023380521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo C, Suzuki H, Itoda M, Ozawa S, Sawada J, Kobayashi D, Ieiri I, Mine K, Ohtsubo K, Sugiyama Y. Functional analysis of SNPs variants of BCRP/ABCG2. Pharmcol Res. 2004;21:1895–1903. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000045245.21637.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imai Y, Nakane M, Kage K, Tsukahara S, Ishikawa E, Tsuruo T, Miki Y, Sugimoto Y. C421A polymorphism in the human breast cancer resistance protein gene is associated with low expression of Q141K protein and low-level drug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poonkuzhali B, Lamba J, Strom S, Sparreboom A, Thummel K, Watkins P, Schuetz E. Association of breast cancer resistance protein/ABCG2 phenotypes and novel promoter and intron 1 single nucleotide polymorphisms. Drug Metab & Dispos. 2008;36:780–795. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamber CP, Lamba JK, Yasuda K, Farnum J, Thummel K, Schuetz JD, Schuetz EG. Natural allelic variants of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and their relationship to BCRP expression in human intestine. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]