Abstract

Vulcanisaeta distributa Itoh et al. 2002 belongs to the family Thermoproteaceae in the phylum Crenarchaeota. The genus Vulcanisaeta is characterized by a global distribution in hot and acidic springs. This is the first genome sequence from a member of the genus Vulcanisaeta and seventh genome sequence in the family Thermoproteaceae. The 2,374,137 bp long genome with its 2,544 protein-coding and 49 RNA genes is a part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: hyperthermophilic, acidophilic, non-motile, microaerotolerant anaerobe, Thermoproteaceae, Crenarchaeota, GEBA

Introduction

Strain IC-017T (= DSM 14429 = JCM 11212) is the type strain of the species Vulcanisaeta distributa, which is the type species of its genus Vulcanisaeta [1]. The only other species in the genus is V. souniana [1,2]. The genus name derives from the Latin words ‘vulcanicus’ meaning volcanic, and ‘saeta’ meaning stiff hair, to indicate a rigid rod inhabiting volcanic hot springs [1]. The species epithet derives from the Latin ‘distributa’, referring to the wide distribution of strains belonging to this species [1]. The type strain IC-017T was isolated from a hot spring in Ohwakudani, Kanagawa, Japan [1]. Fourteen additional strains [IC-019, IC-029 (= JCM 11213), IC-030, IC-032, IC-051, IC-052, IC-058, IC-064 (= JCM 11214), IC-065 (= JCM 11215), IC-124 (= JCM 11216), IC-135 (= JCM 11217), IC-136, IC-140 and IC-141 (= JCM 11218)] are included in this species [1]. At the time of the species description, the terminus ‘distributa’ referred simply to a wide distribution within Japan [1]. However, 16S rRNA sequences which probably belong to the genus Vulcanisaeta (≥95% sequence similarity to V. distributa) have been obtained from 117°C hot deep-sea hydrothermal fluid in the south Mariana area [3]. Clone sequences that are highly similar to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain IC-017T were obtained from an acidic hot spring water at the Tatung Volcano area in Northern Taiwan (99%, FJ797325), the hot Sylvan Spring in Yellowstone National Park (=YNP, USA, 98%, DQ243774), at the Cistern Hot Spring at Norris Geyser Basin in YNP (98%, DQ924709) and also at other springs in YNP (98%, DQ833773). Metagenomic sequences from uncultured clones in YNP (94%, ADKH01000984) also support these observations. The 16S rRNA gene similarity values to non-hot-spring metagenomes, e.g., from marine, soil, or human gut, were all below 83%, indicating that Vulcanisaeta is probably not found in these habitats (status July 2010).

Although it is not the case for the type strain IC-017T, V. distributa recently received further interest, as it was found that strain IC-065 contained a 691 bp large intron within its 16S rRNA sequence [4]. Novel 16S rRNA introns have been found in several members of the family Thermoproteaceae [4]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for V. distributa strain IC-017T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

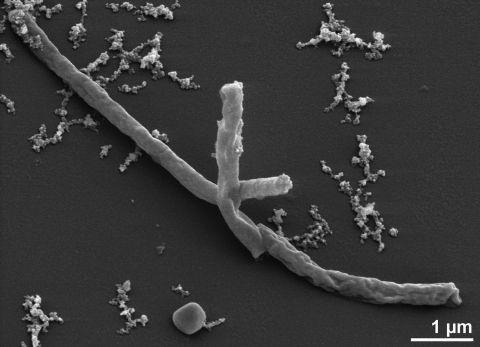

The cells of strain IC-017T are rigid, straight to slightly curved rods (Figure 1 and Table 1)[4]. Occasionally, they bend, branch out, or bear spherical bodies at the terminae (not seen in Figure 1), which have been termed as 'golf clubs'. Most cells are 0.4-0.6 µm in width and 3-7 µm long [4]. Pili have been observed to rise terminally or laterally; motility has not been observed [4]. Usually, strain IC-017T grows anaerobically. However, when cultured in media in which sulfur is replaced by sodium thiosulfate (1.0 g/l), strain IC-017T showed weak growth in a low-oxygen atmosphere (1%), but not in air [4].

Figure 1.

Scanning electron micrograph of V. distributa IC-017T

Table 1. Classification and general features of V. distributa IC-017T according to the MIGS recommendations [5].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Archaea | TAS [6] | |

| Phylum Crenarchaeota | TAS [7,8] | ||

| Class Thermoprotei | TAS [8,9] | ||

| Order Thermoproteales | TAS [10-13] | ||

| Family Thermoproteaceae | TAS [10,12,13] | ||

| Genus Vulcanisaeta | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Vulcanisaeta distributa | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain IC-017 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | not reported | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | rigid, straight to slightly curved rods | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | non-motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | not reported | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | 70-92°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 90°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | 1% NaCl or below | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | microaerotolerant anaerobe | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | yeast extract, peptone, beef extract, casamino acids, gelatin, maltose, starch, malate, galactose, mannose |

TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | heterotrophic | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | acidic hot environments (water, soil, mud) | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | not pathogenic | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [14] | |

| Isolation | acidic hot water | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Ohwakudani, Japan | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | September 1993 | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

35.447 139.642 |

NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | unknown | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | unknown |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [15]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

In contrast to Thermocladium or Caldivirga strains, V. distributa grows well even in the absence of a vitamin mixture or archaeal cell-extract solution in the medium [4]. All seven tested strains of V. distributa were shown to be resistant to chloramphenicol, kanamycin, oleandomycin, streptomycin and vancomycin, but sensitive to erythromycin, novobiocin and rifampicin (all at 100 µg per ml) [4]. V. distributa needs acidic conditions to grow (pH 3.5 to 5.6). Under optimal growth conditions, the doubling time is 5.5 to 6.5 hours [4]. Sulfur or thiosulfate is required as an electron acceptor. Strain IC-017T does not utilize D-arabinose, D-fructose, lactose, sucrose, D-xylose, acetate, butyrate, formate, fumarate, propionate, pyruvate, succinate, methanol, formamide, methylamine or trimethylamine as carbon sources and does not utilize fumarate, malate or nitrate as electron acceptors [4].

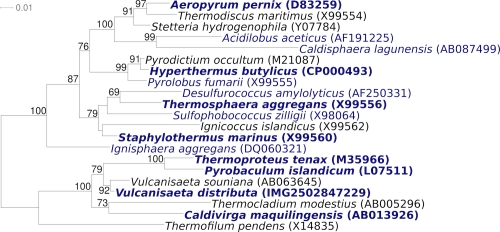

Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of V. distributa IC-017T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequence of the single 16S rRNA gene copy in the genome of strain IC-017T does not differ from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (AB063630).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of V. distributa IC-017T relative to the other type strains within the genus Vulcanisaeta and the type strains of the other genera within Thermoproteales. The tree was inferred from 1,356 aligned characters [16,17] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [18] and rooted with the type strains of the genera of Desulfurococcales and Acidilobales. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 150 bootstrap replicates [19] if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [20] are shown in blue, published genomes [21-24] and INSDC accessions CP000504 and CP00852 in bold.

Chemotaxonomy

Strain IC-017T possesses cyclic and acyclic tetraether core lipids [4]. The major cellular polyamines are norspermidine (1.25), spermidine (0.55), agmatine (0.15), norspermine (0.1) and cadaverine (0.1) (values are in µmol/g wet weight of the cell) [25]. Further chemotaxonomic data are not available.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [26], and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [27]. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [20] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two genomic libraries: one 454 pyrosequence standard library, one 454 PE library (22.9kb insert size) |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 106.3 × pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.0.0-PostRelease- 09/05/2008, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP002100 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | September 23, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01374 | |

| NCBI project ID | 32589 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2502790013 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 14429 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

V. distributa IC-017T, DSM 14429, was grown anaerobically in DSMZ medium 88 (Sulfolobus medium) [28] at 90°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the standard protocol as recommended by the manufacturer.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a 454 sequencing platform. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the JGI website (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/). Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 2.0.0-PostRelease-09/05/2008 (Roche). The initial Newbler assembly consisted of 147 contigs in 13 scaffolds and was converted into a phrap assembly by making fake reads from the consensus, and collecting the read pairs in the 454 paired end library. Draft assemblies were based on 252.4 Mb 454 draft and all of the 454 paired end data. Newbler parameters are -consed -a 50 -l 350 -g -m -ml 20.

The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package (www.phrap.com) was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment in the following finishing process. After the shotgun stage, reads were assembled with parallel phrap (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with gapResolution (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/), Dupfinisher [29], or sequencing cloned bridging PCR fragments with subcloning or transposon bombing (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) [30]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, by PCR and by Bubble PCR primer walks (J.-F.Chang, unpublished). A total of 97 additional reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. The final assembly contains 0.8 million pyrosequencing reads that provide 106.3 x coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [31] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [32]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [33].

Genome properties

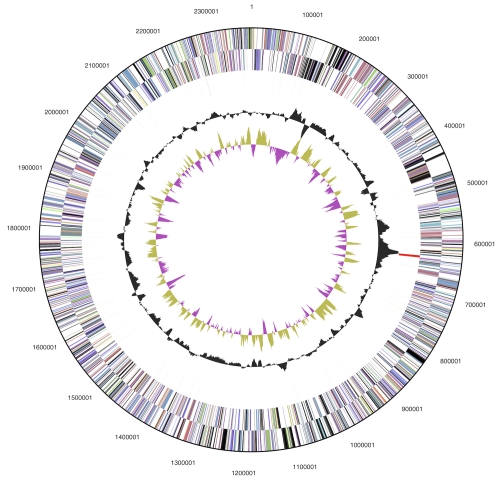

The genome consists of a 2,374,137 bp long chromosome with a 45.4% GC content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 2,593 genes predicted, 2,544 were protein-coding genes, and 49 RNAs; fifty one pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (57.2%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,374,137 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,136,210 | 98.11% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,078,516 | 45.43% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 2,593 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 49 | 1.89% |

| rRNA operons | 1 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,544 | 98.11% |

| Pseudo genes | 51 | 1.97% |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,483 | 57.19% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 327 | 12.61% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,548 | 59.70% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 1,665 | 64.21% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 205 | 7.91% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 591 | 22.79% |

| CRISPR repeats | 18 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 161 | 9.6 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 4 | 0.2 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 65 | 3.9 | Transcription |

| L | 67 | 4.0 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 4 | 0.2 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 18 | 1.1 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 13 | 0.8 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 25 | 1.5 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 61 | 3.6 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 8 | 0.5 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.1 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 20 | 1.2 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 64 | 3.8 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 167 | 10.0 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 96 | 5.7 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 160 | 9.5 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 55 | 3.3 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 64 | 3.8 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 69 | 4.1 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 59 | 3.5 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 29 | 1.7 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 263 | 15.7 | General function prediction only |

| S | 160 | 9.5 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,045 | 40.3 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, UT-Battelle and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1 and SI 1352/1-2.

References

- 1.Itoh T, Suzuki K, Nakase T. Vulcanisaeta distributa gen. nov., sp. nov., and Vulcanisaeta souniana sp. nov., novel hyperthermophilic, rod-shaped crenarchaeotes isolated from hot springs in Japan. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1097-1104 10.1099/ijs.0.02152-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Euzéby JP. List of bacterial names with standing in nomenclature: A folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura H, Ishibashi JI, Masuda H, Kato K, Hanada S. Selective phylogenetic analysis targeting 16S rRNA genes of hyperthermophilic archaea in the deep-subsurface hot biosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007; 73:2110-2117 10.1128/AEM.02800-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoh T, Nomura N, Sako Y. Distribution of 16S rRNA introns among the family Thermoproteaceae and their evolutionary implications. Extremophiles 2003; 7:229-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrity GM, Holt JG. 2001. Phylum AI. Crenarchaeota phy. nov., p. 169-210. In GM Garrity, DR Boone, and RW Castenholz (eds.), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition ed, vol. 1. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 8.List editor. Validation List No.85: Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:685-690 10.1099/ijs.0.02358-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reysenbach AL. 2001. Class I. Thermoprotei class. nov., p. 169. In GM Garrity, DR Boone, RW Castenholz (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition ed, vol. 1. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zillig W, Stetter KO, Schäfer W, Janekovic D, Wunderl S, Holz J, Palm P. Thermoproteales: a novel type of extremely thermoacidophilic anaerobic archaebacteria isolated from Icelandic solfataras. Zentralbl Bakteriol Hyg 1. Abt Orig C 1981; 2:205-227 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judicial Commission of the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes The nomenclatural types of the orders Acholeplasmatales, Halanaerobiales, Halobacteriales, Methanobacteriales, Methanococcales, Methanomicrobiales, Planctomycetales, Prochlorales, Sulfolobales, Thermococcales, Thermoproteales and Verrucomicrobiales are the genera Acholeplasma, Halanaerobium, Halobacterium, Methanobacterium, Methanococcus, Methanomicrobium, Planctomyces, Prochloron, Sulfolobus, Thermococcus, Thermoproteus and Verrucomicrobium, respectively. Opinion 79. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:517-518 10.1099/ijs.0.63548-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burggraf S, Huber H, Stetter KO. Reclassification of the crenarchaeal orders and families in accordance with 16S rRNA sequence data. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:657-660 10.1099/00207713-47-3-657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.List editor. Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB: List No. 8. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1982; 32:266-268 10.1099/00207713-32-2-266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Classification of bacteria and archaea in risk groups. TRBA 466.

- 15.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web Servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawarabayasi Y, Hino Y, Horikawa H, Yamazaki S, Haikawa Y, Jin-no K, Takahashi M, Sekine M, Baba S, Ankai A, et al. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic hyper-thermophilic crenarchaeon, Aeropyrum pernix K1. DNA Res 1999; 6:83-101, 145-152 10.1093/dnares/6.2.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brügger K, Chen L, Stark M, Zibat A, Redder P, Ruepp A, Awayez M, She Q, Garrett RA, Klenk HP. The genome of Hyperthermus butylicus: a sulfur-reducing, peptide fermenting, neutrophilic Crenarchaeote growing up to 108 degrees C. Archaea 2006; 2:127-135 10.1155/2007/745987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson IJ, Dharmarajan L, Rodriguez J, Hooper S, Porat I, Ulrich LE, Elkins JG, Mavromatis K, Sun H, Land M, et al. The complete genome sequence of Staphylothermus marinus reveals differences in sulfur metabolism among heterotrophic Crenarchaeota. BMC Genomics 2009; 10:145 10.1186/1471-2164-10-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spring S, Rachel R, Lapidus A, Davenport K, Tice H, Copeland A, Cheng JF, Lucas S, Chen F, Nolan M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Thermosphaera aggregans type strain (M11TLT). Stand Genomic Sci 2010; 2:245-259 10.4056/sigs.821804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamana K, Tanaka T, Hosoya R, Niitsu M, Itoh T. Cellular polyamines of the acidophilic, thermophilic and thermoacidophilic archaebacteria, Acidilobus, Ferroplasma, Pyrobaculum, Pyrococcus, Staphylothermus, Thermococcus, Thermodiscus and Vulcanisaeta. J Gen Appl Microbiol 2003; 49:287-293 10.2323/jgam.49.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klenk HP, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol 2010; 33:175-182 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 29.Cliff S. Han, Patrick Chain. 2006. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher. In: Proceeding of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics & computational biology. Hamid R Arabnia & Homayoun Valafar (eds), CSREA Press. June 26-29, 2006: 141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter J, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A gene prediction improvement pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]