Abstract

Sulfurimonas autotrophica Inagaki et al. 2003 is the type species of the genus Sulfurimonas. This genus is of interest because of its significant contribution to the global sulfur cycle as it oxidizes sulfur compounds to sulfate and by its apparent habitation of deep-sea hydrothermal and marine sulfidic environments as potential ecological niche. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. This is the second complete genome sequence of the genus Sulfurimonas and the 15th genome in the family Helicobacteraceae. The 2,153,198 bp long genome with its 2,165 protein-coding and 55 RNA genes is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: mesophilic, facultatively anaerobic, sulfur metabolism, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, spermidine, Gram-negative, Helicobacteriaceae, Epsilonproteobacteria, GEBA

Introduction

Strain OK10T (= DSM 16294 = ATCC BAA-671 = JCM 11897) is the type strain of Sulfurimonas autotrophica [1], which is the type species of its genus Sulfurimonas [1,2]. Together with S. paralvinellae and S. denitrificans, the latter of which was formerly classified as Thiomicrospira denitrificans [3]. There are currently three validly named species in the genus Sulfurimonas [4,5]. The autotrophic and mixotrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacteria such as the members of the genus Sulfurimonas are believed to contribute significantly to the global sulfur cycle [6]. The genus name derives from the Latin word ‘sulphur’, and the Greek word ‘monas’, meaning a unit, in order to indicate a “sulfur-oxidizing rod” [1]. The species epithet derives from the Greek word ‘auto’, meaning self, and from the Greek adjective ‘trophicos’ meaning nursing, tending or feeding, in order to indicate its autotrophy [1]. S. autotrophica strain OK10T, like S. paralvinellae strain GO25T (= DSM 17229), was isolated from the surface of a deep-sea hydrothermal sediment on the Hatoma Knoll in the Mid-Okinawa Trough hydrothermal field [1,2]. Thus, the members of the genus Sulfurimonas appear to be free living, whereas the other members of the family Helicobacteraceae, the genera Helicobacter and Wolinella, appear to be strictly associated with the human stomach and the bovine rumen, respectively. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for S. autotrophica OK10T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

There exist currently no experimental reports that indicate further cultivated strains of this species. The type strains of S. denitrificans and S. paralvinellae share 93.5% and 96.3% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with strain OK10T. Further analysis also revealed that strain OK10T shares high similarity (99.1%) with the uncultured clone sequence PVB-12 (U15104) obtained from a microbial mat near the deep-sea hydrothermal vent in the Loihi Seamont, Hawaii [7]. This further corroborates the distribution of S. autotrophica in hydrothermal vents. The 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities of strain OK10T to metagenomic libraries (env_nt) were 87% or less, indicating the absence of further members of the species in the environments screened so far (status August 2010).

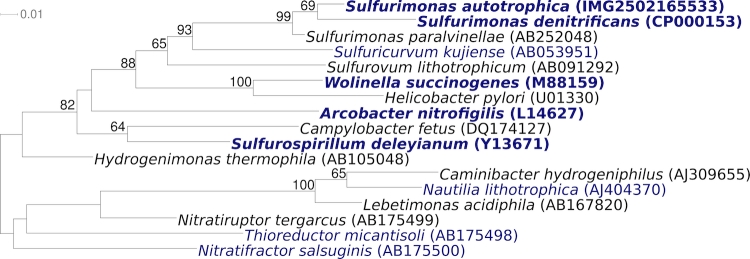

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of S. autotrophica OK10T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the four 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome differ from each other by up to four nucleotides, and differ by up to three nucleotides from the previously published sequence (AB088431).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of S. autotrophica OK10T relative to the type strains of the other species within the genus and the type strains of the other genera within the order Campylobacterales. The tree was inferred from 1,327 aligned characters [8,9] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [10] and rooted in accordance with current taxonomy [11]. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 350 bootstrap replicates [12] if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [13] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold [14,15], such as the recently published GEBA genomes from Sulfurospirillum deleyianum [16] and Arcobacter nitrofigilis [17].

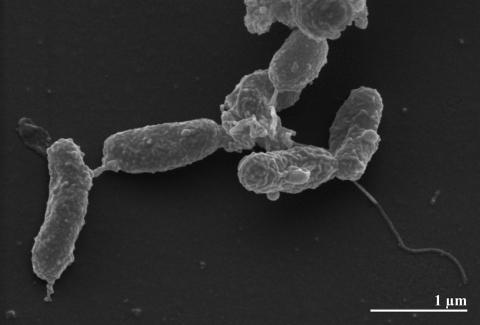

The cells of strain OK10T are Gram-negative, occasionally slightly curved rods of 1.5–2.5 × 0.5-1.0 µm (Figure 2 and Table 1) [1]. On solid medium, the cells form white colonies [1]. Under optimal conditions, the generation time of S. autotrophica strain OK10T is approximately 1.4 h [1,2]. The reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle for autotrophic CO2 fixation is present in strain OK10T, as shown by PCR amplification of the respective genes [28]. Moreover, the activities of several rTCA key enzymes (ACL, ATP dependent citrate lyase; POR, pyruvate:acceptor oxidoreductase; OGOR, 2-oxoglutarase:accecptor oxidoreductase; ICDH, isocytrate dehydrogenase) have been determined, also in comparison to S. paralvinellae and S. denitrificans [28]. There were no enzyme activities for the phosphoenolpyruvate and ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (Calvin-Benson) pathways detected in strain OK10T [28], though the latter is apparently active in S. thermophila [28]. Also, soluble hydrogenase activity was not found in strain OK10T [28]. With respect to sulfur oxidation, enzyme activity for SOR (sulfite oxidoreductase) but not for APSR (adenosine 5′-phosphate sulfate reductase) and TSO (thiosulfate-oxidizing enzymes) were detected [28]. A detailed comparison of these enzyme activities to S. paralvinellae and S. denitrificans is given in Takai et al. [28]. Elemental sulfur, thiosulfate or sulfide is utilized as the sole electron donor for chemolithoautotrophic growth with O2 as electron acceptor. Thereby thiosulfate is oxidized to sulfate [1]. Organic substrates and H2 are not utilized as electron donors and only oxygen is utilized as an electron acceptor [28]. Strain OK10T requires 4% sea salt for growth [1] and is not able to reduce nitrate [2].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of S. autotrophica OK10T

Table 1. Classification and general features of S. autotrophica OK10T according to the MIGS recommendations [18].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [19] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [20] | ||

| Class Epsilonproteobacteria | TAS [21,22] | ||

| Order Campylobacterales | TAS [23,24] | ||

| Family Helicobacteraceae | TAS [24,25] | ||

| Genus Sulfurimonas | TAS [1,2] | ||

| Species Sulfurimonas autotrophica | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain OK10 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | short rods, occasionally slightly curved rods | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | by monotrichous, polar flagellum | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | 10°C - 40°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 23°C - 26°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | 4% NaCl | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | aerobic | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | CO2 | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | chemolithoautotrophic, S0, Na2S2O3 and Na2S x 9H2O |

TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | hydrothermal deep-sea sediments | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | not reported | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [26] | |

| Isolation | Mid-Okinawa Trough hydrothermal sediments | TAS [1,7] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Japan, Hatoma Knoll | TAS [1,7] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 2003 or before | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

27.27 127.17 |

TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | sediment surface | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported | NAS |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [27]. If the evidence code is IDA, then it was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Chemotaxonomy

The major cellular fatty acids found in strain OK10T are C14:0 (8.4%), C16:1cis (45.2%), C16:0 (37.1%) and C18:1trans (9.4%) [1]. Further fatty acids were not reported [1]. The only polyamine identified in S. autotrophica is spermidine [29]. Spermidine was also found in another representative of the order Campylobacterales, Sulfuricurvum kujiense. For comparison, Hydrogenimonas thermophila, the type species and genus of the family Hydrogenimonaceae in the order Campylobacterales, contains both spermidine and spermine as the major polyamines [29]. The cellular fatty acid composition of S. autotrophica was compared with that of other autotrophic Epsilonproteobacteria from deep-sea hydrothermal vents: Nautilia profundicola AmHT, Lebetimonas acidiphila Pd55T, Hydrogenimonas thermophila EP1-55-1%T, and Nitratiruptor tergarcus MI55-1T [30]. It was found that S. autotrophica strain OK10T has much higher levels of the fatty acid C16:1cis (45.2%) than do other Epsilonproteobacteria from hydrothermal vents express (3.6%-28.8%) [2,30]. On another hand, the percentage of C18:1trans was the lowest in S. autotrophica: (9.4%), while other Epsilonproteobacteria contained 20.0%-73.3% [30]. C14:0 (8.4%) was also more abundant in strain OK10T than in other strains [30].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [31], and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [32]. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [13] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Four genomic libraries: Sanger 8 kb pMCL200 library, 454 pyrosequence standard library, 454 pyrosequence paired end (PE) library, Illumina standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 GS FLX Titanium, Illumina GAii |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 3.7 × Sanger; 121.7 × pyrosequence, 30.0 × Illumina |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.0.00.20-PostRelease-11-05-2008-gcc-3.4.6, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP002205 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | September 15, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01373 | |

| NCBI project ID | 31347 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2502082114 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 16294 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

S. autotrophica strain OK10T, DSM 16294, was grown in DSMZ medium 1011 (MJ medium) [33] at 24°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit (Epicenter MGP04100) following the standard protocol as recommended by the manufacturer, with modification st/LALM for cell lysis as described in Wu et al. [32].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger, 454 and Illumina sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the JGI website (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/). Illumina sequencing data was assembled with VELVET [34], and the consensus sequences were shredded into 1.5 kb overlapped fake reads and used for the assembly with 454 and Sanger data. Contigs resulting from a 454 Newbler (2.0.00.20-PostRelease-11-05-2008-gcc-3.4.6) assembly were shredded into 2 kb fake reads, which were assembled with Sanger data. The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package (www.phrap.com) was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment. After the shotgun stage, reads were assembled with parallel phrap (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) [35]. A total of 790 additional custom primer reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. Illumina reads were also used to improve the final consensus quality using an in-house developed tool - the Polisher [36]. Together, the combination of the Illumina and 454 sequencing platforms provided 155.4 × coverage of the genome. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [37] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [38]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [39].

Genome properties

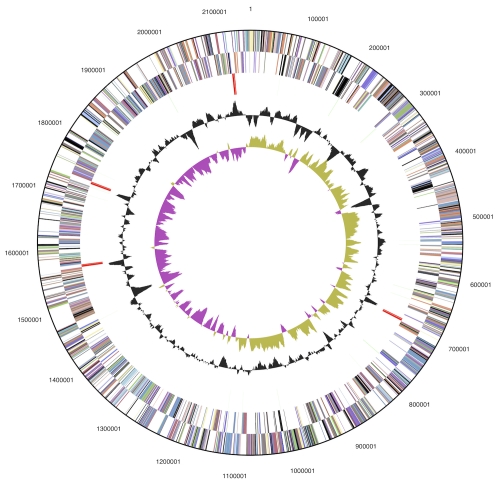

The genome consists of a 2,153,198 bp long chromosome with a 35.2% GC content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 2,220 genes predicted, 2,165 were protein-coding genes, and 55 RNAs; seven pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (69.1%) were assigned with a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,153,198 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,043,048 | 94.88% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 758,696 | 35.24% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 2,220 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 55 | 2.48% |

| rRNA operons | 4 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,165 | 97.52% |

| Pseudo genes | 7 | 032% |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,534 | 69.10% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 141 | 6.35% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,590 | 71.62% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 1,656 | 74.59% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 429 | 19.32% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 563 | 25.36% |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 143 | 8.1 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 70 | 4.0 | Transcription |

| L | 82 | 4.6 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 22 | 1.2 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 30 | 1.7 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 158 | 8.9 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 126 | 7.1 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 77 | 4.3 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 69 | 3.9 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 89 | 5.0 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 141 | 8.0 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 62 | 3.5 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 121 | 6.8 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 49 | 2.8 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 107 | 6.0 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 36 | 2.0 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 103 | 5.8 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 12 | 0.7 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 158 | 8.9 | General function prediction only |

| S | 119 | 6.7 | Function unknown |

| - | 630 | 28.4 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Petra Aumann for growing S. autotrophica cultures and Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis (both at DSMZ). This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, UT-Battelle and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-2.

References

- 1.Inagaki F, Takai K, Kobayashi H, Nealson KH, Horikoshi K. Sulfurimonas autotrophica gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel sulfur-oxidizing ε-proteobacterium isolated from hydrothermal sediments in the Mid-Okinawa Trough. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:1801-1805 10.1099/ijs.0.02682-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takai K, Suzuki M, Satoshi N, Masayuki M, Yohey S, Inagaki F, Koki H. Sulfurimonas paralvinellae sp. nov., a novel mesophilic, hydrogen- and sulfur-oxidizing chemolithoautotroph within the Epsilonproteobacteria isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent polychaete nest, reclassification of Thiomicrospira denitrificans as Sulfurimonas denitrificans comb. nov. and emended description of the genus Sulfurimonas. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1725-1733 10.1099/ijs.0.64255-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoor T. A new type of thiosulfate oxidizing, nitrate reducing microorganism: Thiomicrospira denitrificans sp. nov. Neth J Sea Res 1975; 9:344-350 10.1016/0077-7579(75)90008-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Euzéby JP. List of bacterial names with standing in nomenclature: A folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrity G. NamesforLife. BrowserTool takes expertise out of the database and puts it right in the browser. Microbiol Today 2010; 7:1 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sievert SM, Scott KM, Klotz MG, Chain PS, Hauser LJ, Hemp J, Hügler M, Land M, Lapidus A, Larimer FW, et al. Genome of the epsilonproteobacterial chemolithoautotroph Sulfurimonas denitrificans. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:1145-1156 10.1128/AEM.01844-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyer CL, Dobbs FC, Karl DM. phylogenetic diversity of the bacterial community from a microbial mat at an active, hydrothermal vent system, Loihi Seamount, Hawaii. Appl Environ Microbiol 1995; 61:1555-1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A Rapid Bootstrap Algorithm for the RAxML Web Servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarza P, Richter M, Peplies J, Euzeby J, Amann R, Schleifer KH, Ludwig W, Glöckner FO, Rosselló-Móra R. The All-Species Living Tree project: A 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains. Syst Appl Microbiol 2008; 31:241-250 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baar C, Eppinger M, Raddatz G, Simon J, Lanz C, Klimmek O, Nandakumar R, Gross R, Rosinus A, Keller H, et al. Complete genome sequence and analysis of Wolinella succinogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:11690-11695 10.1073/pnas.1932838100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baltrus DA, Amieva MR, Covacci A, Lowe TM, Merrell DS, Ottemann KM, Stein M, Salama NR, Guillemin K. The complete genome sequence of Helicobacter pylori Strain G27. J Bacteriol 2009; 191:447-448 10.1128/JB.01416-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikorski J, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Rio TGD, Nolan M, Lucas S, Chen F, Tice H, Cheng JF, Saunders E, et al. Complete genome sequence of Sulfurospirillum deleyianum type strain (5175T). Stand Genomic Sci 2010; 2:149-157 10.4056/sigs.671209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pati A, Gronow S, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Rio TGD, Nolan M, Lucas S, Tice H, Cheng JF, Han C, et al. Complete genome sequence of Arcobacter nitrofigilis type strain (CIT). Stand Genomic Sci 2010; 2:300-308 10.4056/sigs.912121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1. Springer, New York 2001;119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Validation List No 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class V. Epsilonproteobacteria class. nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd edn, vol. 2 (The Proteobacteria), part C (The Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, and Epsilonproteobacteria), Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1145. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity GM, Lilburn T. Order I. Campylobacterales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1145. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Validation List No 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TC. Family II. Helicobacteraceae fam. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1168. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Classification of. Bacteria and Archaea in risk groups. www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 27.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takai K, Campbell BJ, Cary SC, Suzuki M, Oida H, Nunoura T, Hirayama H, Nakagawa S, Suzuki Y, Inagaki F, et al. Enzymatic and genetic characterization of carbon and energy metabolisms by deep-Sea hydrothermal chemolithoautotrophic isolates of Epsilonproteobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005; 71:7310-7320 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7310-7320.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamana K, Sato W, Gouma K, Yu J, Ino Y, Umemura Y, Mochizuki C, Tatatsuka K, Kigure Y, Tanaka N, et al. Cellular polyamine catalogues of the five classes of the phylum Proteobacteria: distributions of homospermidine within the class Alphaproteobacteria, hydroxyputrescine within the class Betaproteobacteria, norspermidine within the class Gammaproteobacteria, and spermine within the classes Deltaproteobacteria and Epsilonproteobacteria. Ann Gunma Health Sci 2006; 27:1-16 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith JL, Campbell BJ, Hanson TE, Zhang CL, Cary SC. Nautilia profundicola sp. nov., a thermophilic, sulfur-reducing epsilonproteobacterium from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:1598-1602 10.1099/ijs.0.65435-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klenk HP, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol 2010; 33:175-182 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 34.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008; 18:821-829 10.1101/gr.074492.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter J, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lapidus A, LaButti K, Foster B, Lowry S, Trong S, Goltsman E. POLISHER: An effective tool for using ultra short reads in microbial genome assembly and finishing. AGBT, Marco Island, FL, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A gene prediction improvement pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]