Abstract

Summary: ESS++ is a C++ implementation of a fully Bayesian variable selection approach for single and multiple response linear regression. ESS++ works well both when the number of observations is larger than the number of predictors and in the ‘large p, small n’ case. In the current version, ESS++ can handle several hundred observations, thousands of predictors and a few responses simultaneously. The core engine of ESS++ for the selection of relevant predictors is based on Evolutionary Monte Carlo. Our implementation is open source, allowing community-based alterations and improvements.

Availability: C++ source code and documentation including compilation instructions are available under GNU licence at http://bgx.org.uk/software/ESS.html.

Contact: l.bottolo@imperial.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, biological sciences have taken full advantage of rather inexpensive high-throughput technologies. New experiments at a systemic level have been conceived to dissect the role of genetic and environmental factors in the development of common diseases or the identification of risk factors for complex phenotypes (Heinig et al., 2010). The dimensions and diversity of available genetic, genomics and other 'omics data sets pose new theoretical and computational problems requiring multi-level data integration and efficient statistical analysis tools.

When the aim is to predict the variation of pathophysiological or complex phenotypes, regression models are widely used. In this set up, Bayesian variable selection (BVS) allows the construction of parsimonious regression models for high-dimensional datasets, adopting prior specifications that translate expected sparsity of the underlying biology and facilitate the interpretation of the results. Moreover, in problems where no single model stands out, model uncertainty is taken into account, reporting competing models with their posterior evidence.

ESS++ is a C++ implementation of a fully BVS approach for linear regression that can analyse single and multiple responses in an integrated way (Bottolo and Richardson, 2010; Petretto et al., 2010). Whereas other approaches (Servin and Stephens, 2007) consider one predictor at the time, ESS++ performs an efficient search for combinations of covariates that predict the variation of single and multiple responses. Like Shotgun Stochastic Search (Hans et al., 2007), ESS++ is also designed to work under the “large p, small n” paradigm i.e. when the number of predictors p is large with respect to the number of observations n, thus making fully Bayesian analysis feasible in genetics/genomics experiments.

When the number of predictors is large, the multimodality of the model space is a known issue in variable selection. ESS++ explores the 2p-dimensional model space using an extension of parallel tempering called Evolutionary Monte Carlo that combines Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) and genetic algorithms. Specifically, ESS++ relies on running multiple tempered chains in parallel which exchange information about set of covariates that are selected in the regression models. Since chains with higher temperatures flatten the posterior density, global moves (between chains) allow the algorithm to jump from one local mode to another. Local moves (within-chains) permit the fine exploration of alternative models, resulting in a combined algorithm that ensures that the chains mix efficiently and do not become trapped in local modes.

2 EXAMPLES OF ESS++ APPLICATION

In this section, we present the results of the application of ESS++ to investigate genetic regulation. To discover the genetic causes of variation in the expression (i.e. transcription) of genes, gene expression data are treated as a quantitative phenotype while genotype data (SNPs) are used as predictors, a type of analysis known as expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL). In this context, it is important to distinguish cis-eQTLs, where the genetic control points (SNPs) are located close to the location of the transcribed gene, from trans-acting eQTLs, which lie on a different chromosome. Here, we use a larger dataset (Heinig et al., 2010) to reanalyse three genes (Cd36, Ascl3 and Hopx) that were presented in Petretto et al. (2010): in particular, for each gene we investigate the ability of ESS++ to find a parsimonious set of predictors (polygenic regulation) that explain the joint variability of gene expression in seven tissues (adrenal gland, aorta, fat, heart, kidney, liver, skeletal muscle) using 1304 SNPs and 29 observations, taken from the rat inbred lines that were studied.

We run ESS++ for 2.2M sweeps with 200K as burn-in using four chains. The prior requires two main user-defined parameters the a priori expected model size and SD of the model size. We set these to E(pγ)=2 and sd(pγ)=2, respectively, meaning the prior model size is likely to range from 0 to 8.

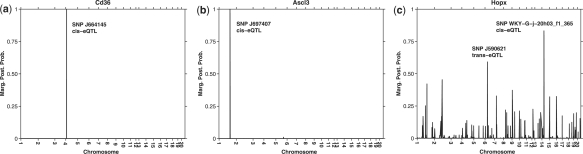

For each gene, Figure 1 shows the marginal posterior probability of inclusion (MPPI), a measure of the marginal contribution of each predictor. For the first gene Cd36, Figure 1a, ESS++ confirms shared genetic effects due to a single cis-eQTL (SNP J664145) and in silico prediction of its systemic effect in all tissues (Aitman et al., 1999). For the second gene Ascl3, Figure 1b, ESS++ also finds a single cis-acting genetic control point (SNP J697407) for the variation of the gene expression in all seven tissues, highlighting the fact that the second trans-acting locus found in Petretto et al. (2010) was specific for the four tissues considered (adrenal gland, fat, heart, kidney). The landscape for the MPPI is much more complicated for the last gene Hopx, Figure 1c, although the locus with highest MPPI (SNP WKY-G-j-20h03f1_365) is the one identified in Petretto et al. (2010).

Fig. 1.

Marginal posterior probability of inclusion (MPPI) obtained running ESS++ on a multiple tissues mapping experiment for three different genes: for each gene, the set of SNPs associated with high MPPI (>0.50) are highlighted, showing monogenic control for (a) Cd36 gene (SNP J664145) and (b) Ascl3 gene (SNP J697407), with evidence for polygenic control for (c) Hopx gene (SNP WKY-G-j-20h03f1_365 and SNP J590621).

One of the distinctive features of ESS++ is also the possibility to look at the best models visited during the MCMC run. For instance, in the Hopx gene the 10 best visited models are all polygenic, SNP WKY-G-j-20h03f1_365 is included in all 10 best visited models and altogether they account for about 15% of the posterior mass. Finally, when compared with the computational time of the Matlab implementation of Petretto et al. (2010), ESS++ runs on a 3 GHz desktop computer, with the same MCMC specifications roughly 15 times faster (in 36, 74, and roughly 400 minutes for the examples above).

3 DOCUMENTATION AND IMPLEMENTATION

ESS++ is written in C++. Documentation of the algorithm (provided with the code and in the Supplementary Material) details not only the installation on different platforms and the contents of the package, but also how to run ESS++.

The command line of ESS++ is extremely simple and it requires few specifications from the user: the response and predictor matrices (-Y file_name, -X file_name); the number of sweeps and the burn-in period (-nsweep int, -burn_in int); if an hyperprior on the regression coefficient is required (-g_set); if the user prefers a standard/detailed output for the summary statistics (-out file_name, -out_full file_name); and if additional output files (MCMC move histories) are required (-history).

The set-up of ESS++ is highly customizable by the user through the modification of the -par file. Among several other settings it is possible to define: the a priori expected value and the SD of the number of predictors (E_P_GAM, SD_P_GAM); the number of chains and their initial distance (NB_CHAINS, B_T); the parameters for the evolutionary part of the algorithm such as the proportion of local and global moves (P_MUTATION); and the weighting of different types of global moves (P_DR). We refer the reader to Table 1 of the accompanying documentation for full details on all the parameters that can be entered in ESS++.

The C++ implementation of ESS++ is open source. Its natural object-oriented structure favours community-based alterations and improvements. ESS++ is memory efficient and can be run, even for very large datasets, on a desktop computer. However, when thousands of observations are collected, the calculation of the (marginal) likelihood, which relies on costly linear algebra operations (QR decomposition, matrix multiplication), becomes rate limiting. A future development for ESS++ will be the translation of some of these linear algebra operations into Compute Unified Device Architecture.

Funding: Medical Research Council Clinical Sciences Centre (L.B.); Nouvelle Société Française d'Athérosclérose and by EU Community's Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. 226756 (to M.C.-H.); PHC ALLIANCE 2009 (19419PH) grant (to D.T. and E.P.), the Wellcome Trust (S.R.L.); EU Community's Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. HEALTH-F4-2010-241504; (EURATRANS to E.P.); MRC grant (G0600609 to S.R.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Aitman T.J., et al. Identification of cd36 (fat) as an insulin-resistance gene causing defective fatty acid and glucose metabolism in hypertensive rats. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:76–83. doi: 10.1038/5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottolo L., Richardson S. Evolutionary stochastic search for bayesian model exploration. Bayesian Anal. 2010;5:583–618. [Google Scholar]

- Hans C., et al. Shotgun stochastic search for ‘large p’ regression. JASA. 2007;102:507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Heinig M., et al. A trans-acting locus regulates an anti-viral expression network and type 1 diabetes risk. Nature. 2010;467:460–464. doi: 10.1038/nature09386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petretto E., et al. New insights into the genetic control of gene expression using a bayesian multi-tissue approach. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servin B., Stephens M. Imputation-based analysis of association studies: candidate regions and quantitative traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.