Abstract

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is a well-accepted physiologic evaluation technique in patients diagnosed with heart failure and in individuals presenting with unexplained dyspnea on exertion. Several variables obtained during CPET, including oxygen consumption relative to heart rate (VO2/HR or O2-pulse) and work rate (VO2/Watt) provide consistent, quantitative patterns of abnormal physiologic responses to graded exercise when left ventricular dysfunction is caused by myocardial ischemia. This concept paper describes both the methodology and clinical application of CPET associated with myocardial ischemia. Initial evidence indicates left ventricular dysfunction induced by myocardial ischemia may be accurately detected by an abnormal CPET response. CPET testing may complement current non-invasive testing modalities that elicit inducible ischemia. It provides a physiologic quantification of the work rate, heart rate and O2 uptake at which myocardial ischemia develops. In conclusion, the potential value of adding CPET with gas exchange measurements is likely to be of great value in diagnosing and quantifying both overt and occult myocardial ischemia and its reversibility with treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Compared to traditional imaging modalities, cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) provides a unique approach to assess exercise-induced ischemia. Accurate detection of myocardial ischemia by CPET relies on the physiologic principle that myocardial contractility depends on the regeneration of high energy phosphate compounds (adenosine tri-phosphate or ATP) in all regions of the myocardium. The ATP must be regenerated during myocardial contraction and/or relaxation by oxidative metabolism (O2-releasing energy from energy supplying substrate). The myocardium becomes ischemic when the work rate is sufficiently high to induce the state of O2 supply - O2 demand imbalance. Measurement of CPET variables in real time, therefore, enables the potential for detection of ischemia-induced LV dysfunction in response to increasing work rate. Hence, patients with or without chest pain or dyspnea can demonstrate physiological responses to exercise characteristic of abrupt reductions in stroke volume. The purpose of this concept paper is to illustrate the potential value of CPET in detecting both macro and microvascular coronary artery disease (CAD).

KEY CPET VARIABLES AND TESTING PRO TOCOL

Thorough description of the numerous variables that can be derived from CPET have been previously described.1–3 The change in the O2-pulse related to increase in work rate and the exercise heart rate (HR) as related to increasing oxygen uptake (VO2) appear to be key CPET responses in the diagnosis of CAD. The O2-pulse, calculated as O2 uptake divided by heart rate (VO2/HR) equals stroke volume (SV)×arteriovenous O2 difference. The latter is relatively reproducible at the anaerobic threshold and peak VO2 if the hemoglobin and oxyhemoglobin saturation are taken into account. Therefore, the SV can be estimated at these points of increasing work rate exercise if gas exchange is simultaneously measured.4,5

Symptom-limited CPET was performed on an electromagnetically-braked cycle ergometer (Ergoselect 100P, Ergoline GmbH, Bitz, Germany) using a customized linear ramp protocol designed to elicit fatigue within 8 – 12 minutes of exercise initiation. Exercise of this duration has been shown to produce the highest peak VO2 values.6,7 The protocol consisted of three minutes of rest, three minutes of pedaling with no load, followed by pedaling against a customized continuously increasing work rate in a ramp pattern to tolerance.8 The ramp work rate was selected based on the patient’s predicted peak VO2, recognizing that VO2 normally increases at a rate of 10 ml/min/watt using previously validated methodology.8

During CPET, a 12-lead ECG (Quark C12, Cosmed Srl, Italy) and a pulse oximeter with a finger probe (Model 100 Pulse Oximeter, Mediaid Inc, Cerritos, CA, USA) were continuously monitored, while blood pressure was manually assessed every two minutes with a cuff sphygmomanometer. A disposable face mask with a 50 – 80 ml dead space (Clear Comfort Air Cushion Face Mask, Hudson RCI, Durham, NC, USA) was used to collect expired air throughout the test. Minute ventilation (VE), carbon dioxide output (VCO2), and oxygen uptake (VO2) were recorded with a breath-by-breath measurement system (Cosmed Quark PFT 4 Ergo, Cosmed Srl, Italy). The flow meter and gas analyzers were calibrated before each test according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Peak VO2 was recorded as the highest consecutive 30 second averaged value during the last minute of exercise or early recovery. The anaerobic threshold (AT) was determined by the V-slope method.9 All responses were monitored throughout rest, exercise and recovery and graphically displayed.

ILLUSTRATION OF A NORMAL AND ABNORMAL RESPONSE

Normal CPET response

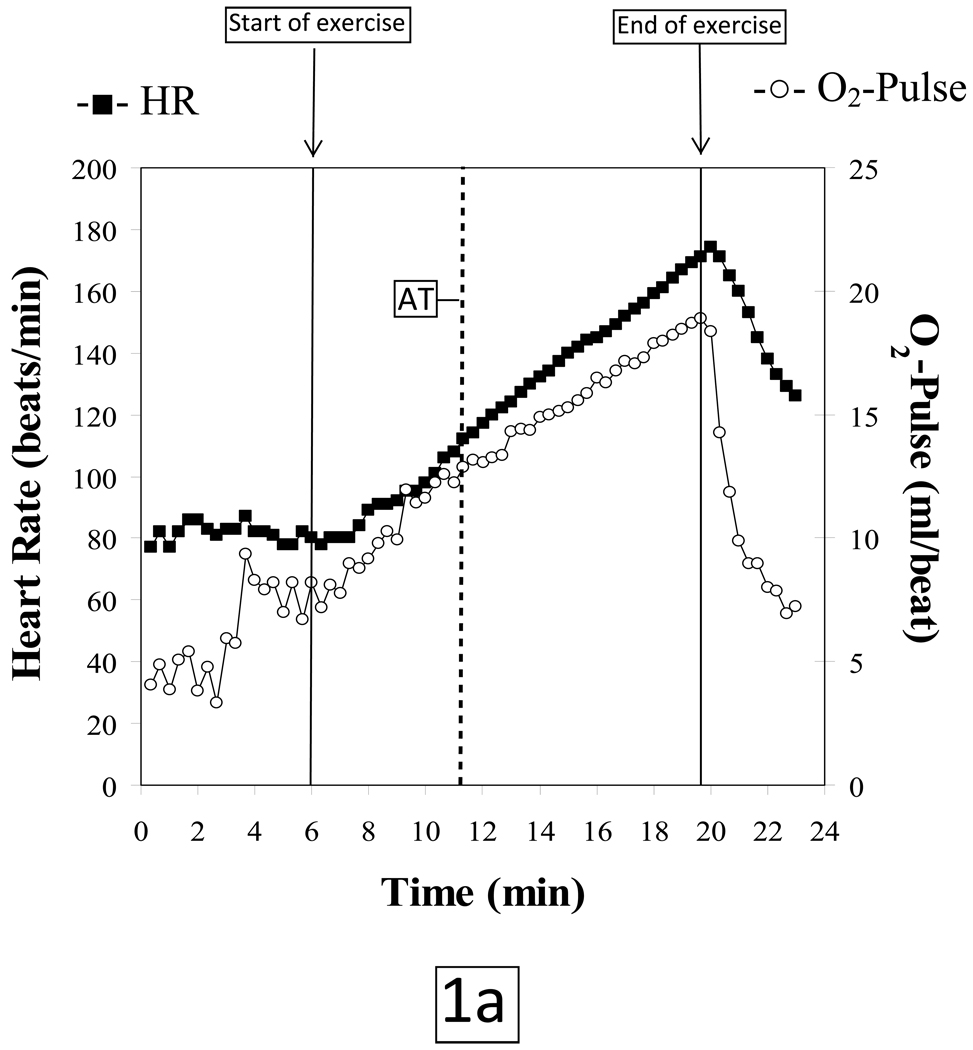

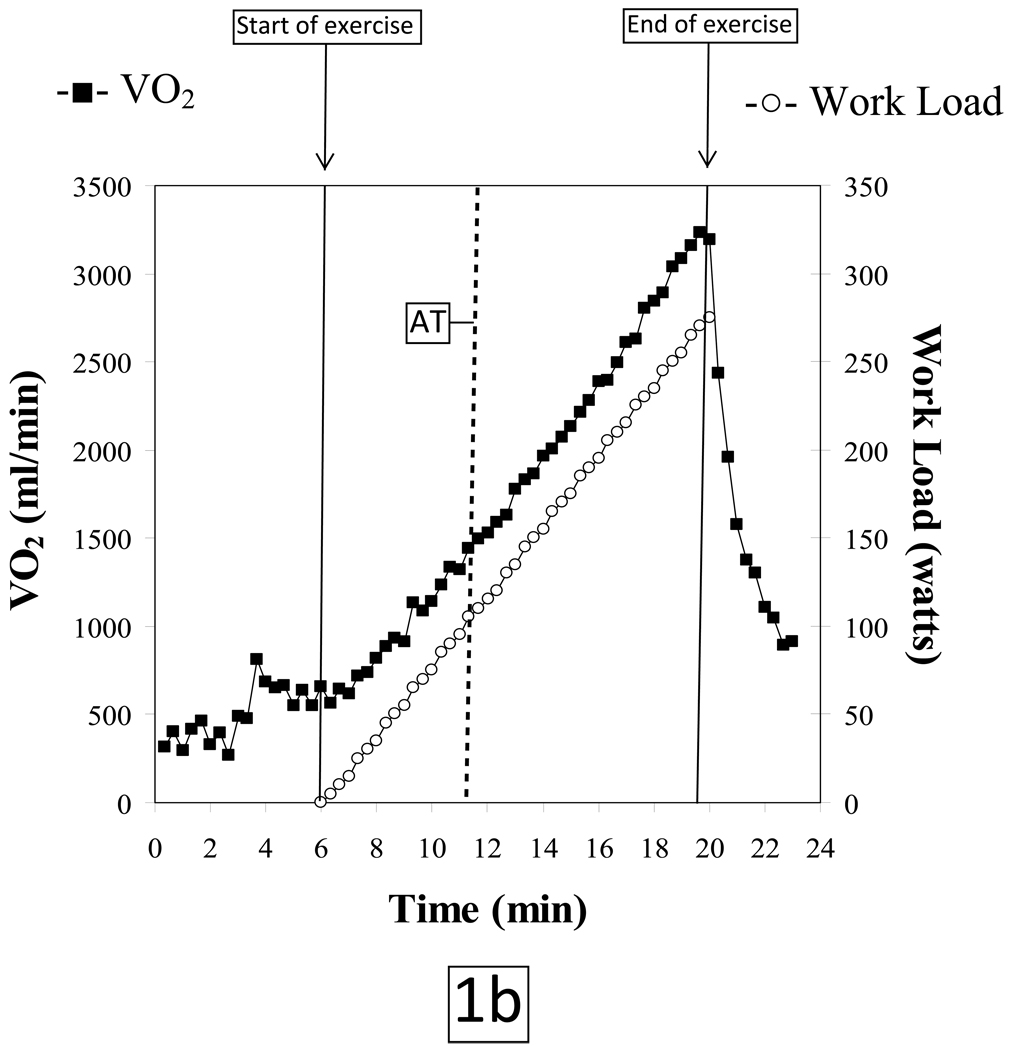

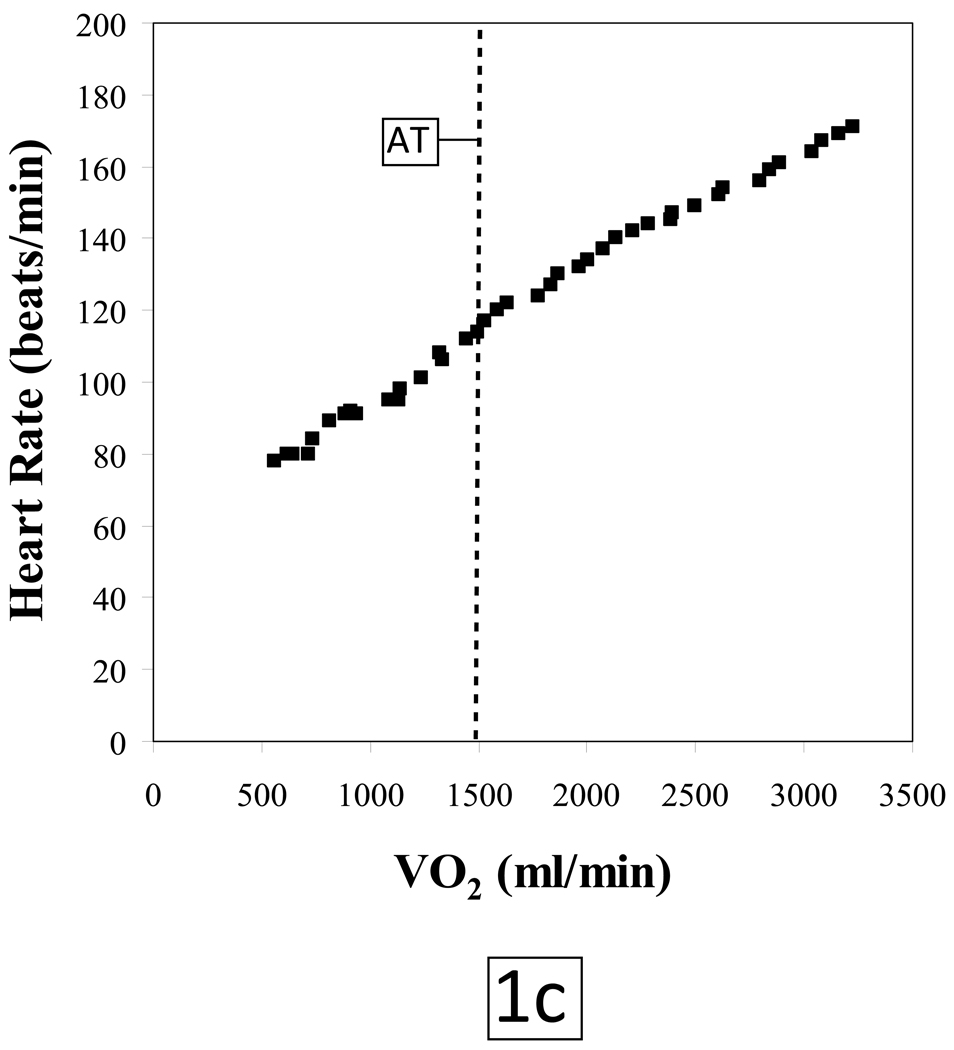

The normal O2-pulse versus time, ΔVO2/ΔWR, and HR versus O2 uptake responses to a progressively increasing work rate during exercise are illustrated in Figures 1a, 1b and 1c, respectively. The test data are from a 49 year old asymptomatic firefighter who was enrolled in a fitness and genetic study of this population. His past medical history was only significant for hypothyroidism; however the subject was euthyroid at the time of testing. He has never smoked, there is no family history of heart disease and he exercises 3–4 times a week. Physical exam and resting ECG were normal.

Figure 1.

AT: Anaerobic threshold, determined by the V-slope method

VO2: Oxygen uptake, milliliters per minute (ml/min)

The subject tolerated the test without complications and put forth a good effort. He achieved a respiratory exchange ratio [VCO2/VO2] of 1.13 at peak exercise indicating a significant lactic acidosis and hence adequate cardiovascular stress. The patient terminated exercise because of leg fatigue. Peak HR was 101% of age-predicted maximum. Blood pressures at rest and at peak exercise were 124/80 mmHg and 220/100 mmHg, respectively. The subject achieved a peak VO2 of 30.3 mlO2•kg−1•min−1 which is 113% of predicted for age, height, weight and sex (predicted peak VO2 ≥ 85% is considered to be normal exercise capacity).8 The VO2 at the anaerobic threshold (AT) of 14.0 mlO2•kg−1•min−1 was likewise within normal limits. O2-pulse increased in a normal linear manner to the predicted peak value (figure 1a); the VO2 increased in a linear manner relative to work load up to peak predicted value (figure 1b) and HR response vs. VO2 was also linear from rest to peak exercise (figure 1c). The ECG revealed isolated premature ventricular beats near peak exercise with no demonstrable ST changes.

Abnormal CPET response

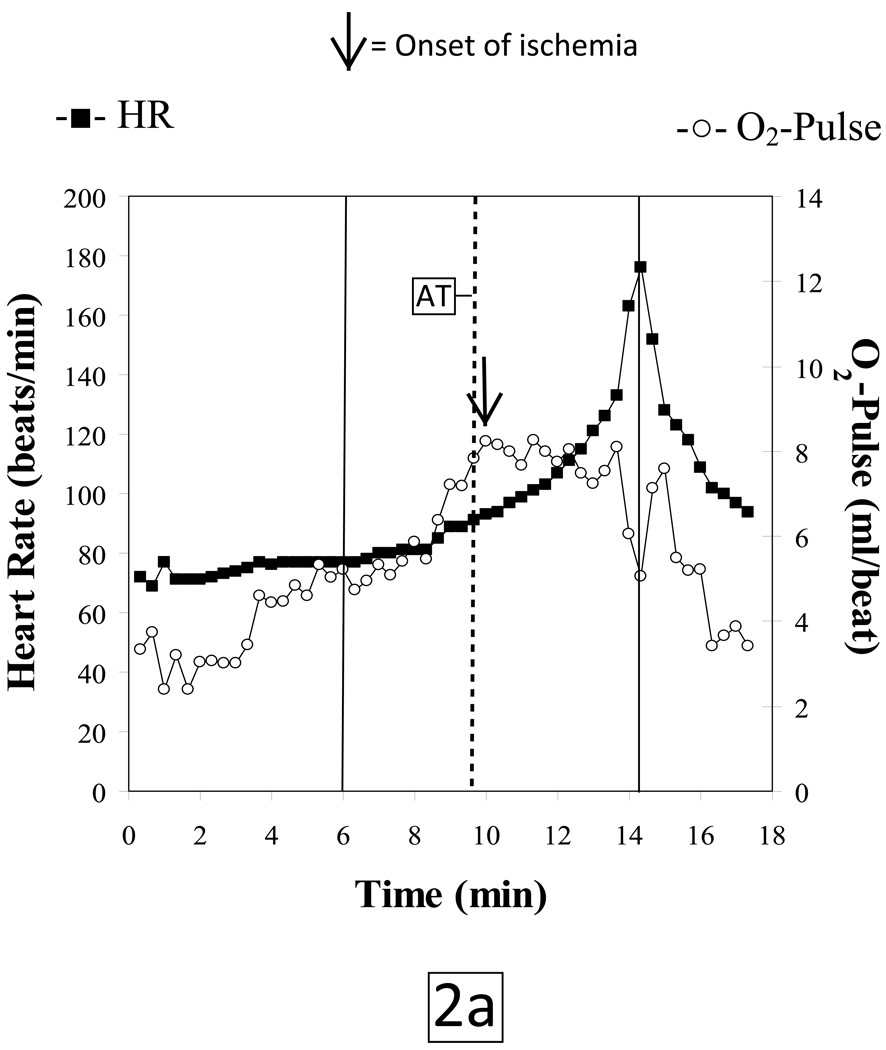

Characteristic CPET findings related to exercise-induced ischemia were evident in a 68 year old female with a 50 pack-year smoking history, hypertension and dyslipidemia who was referred for a CPET as part of pre-operative evaluation. The patient had recently reported claudication with abnormal noninvasive vascular studies, and was scheduled for an elective endovascular peripheral arterial disease procedure. Medications included valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide, rosuvastatin, ezetimibe, niacin, and venlafaxine. Her resting ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with no other abnormalities.

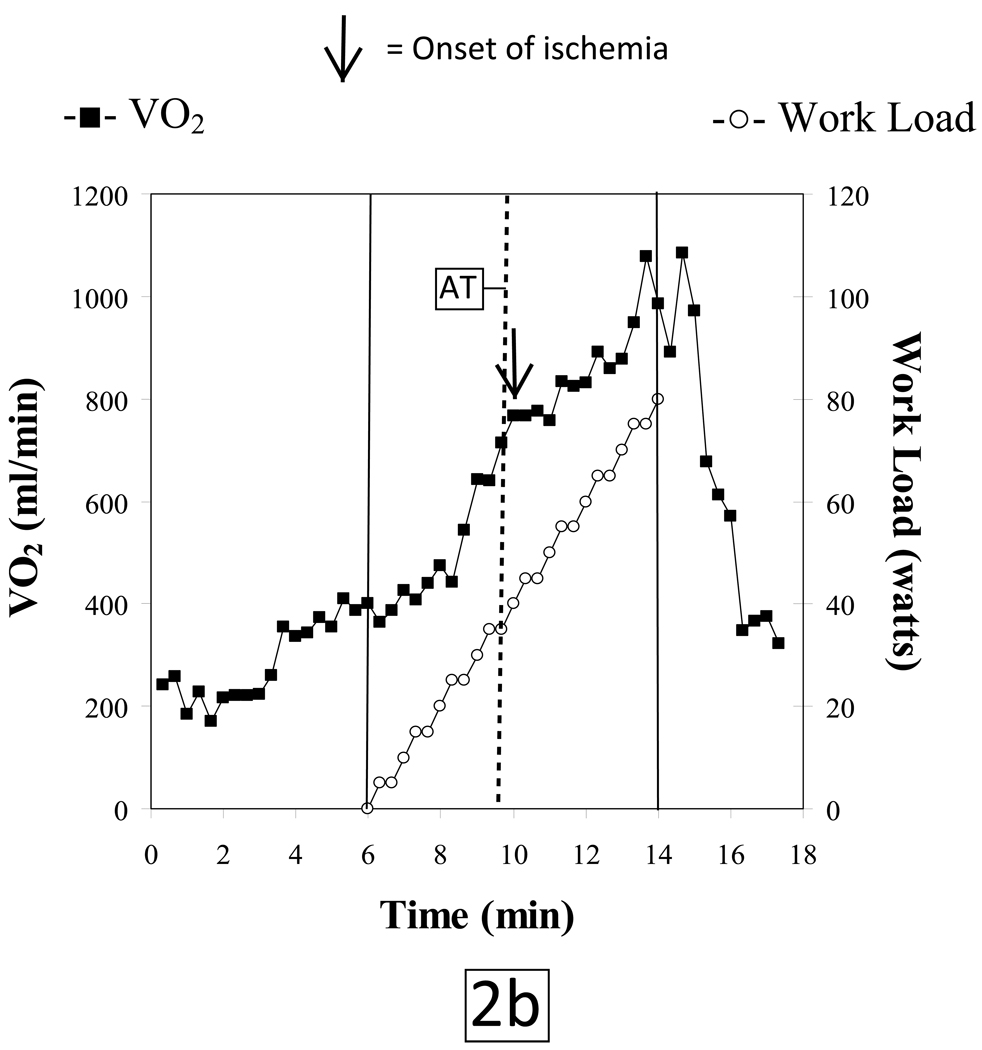

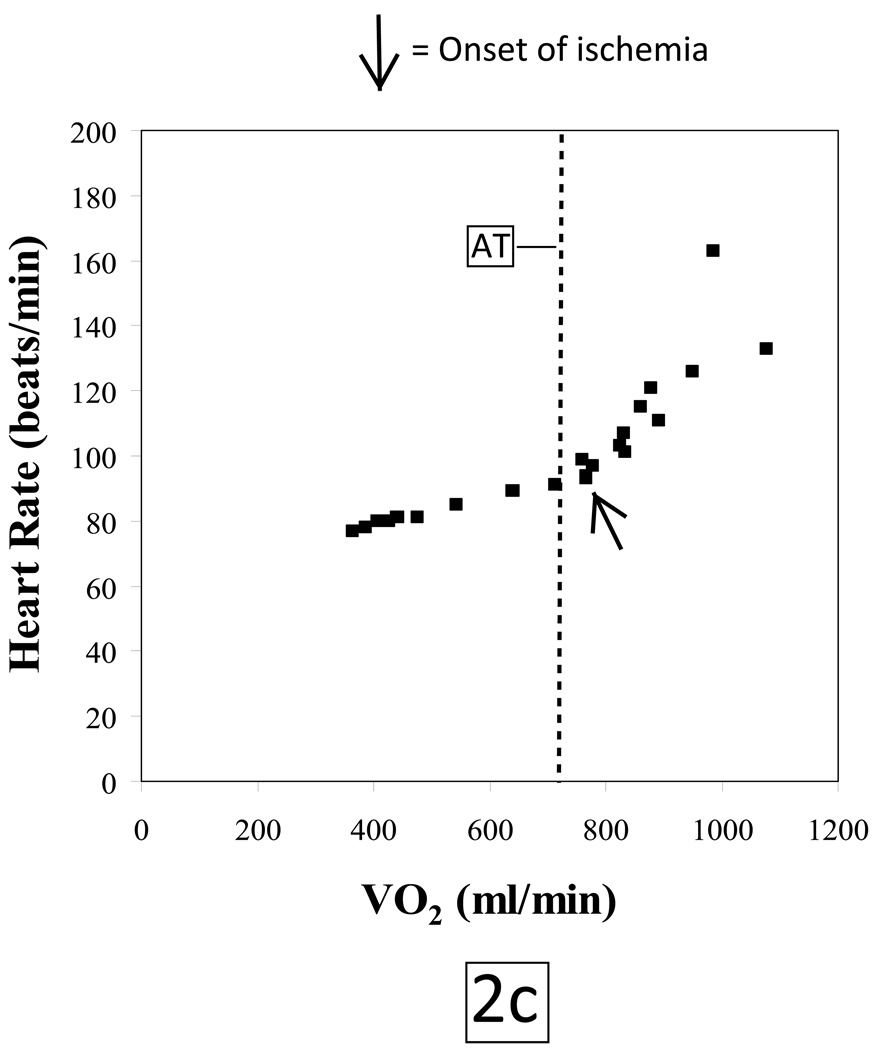

The subject tolerated the test without complications and put forth a good effort. She achieved a respiratory exchange ratio of 1.4 at peak exercise indicative of development of a significant lactic acidosis. The patient terminated exercise because of leg pain. Peak HR was 88% of her age-predicted maximum. Blood pressures at rest and at peak exercise were 148/82 mmHg and 218/96 mmHg, respectively. She achieved a peak VO2 of 17.2 mlO2•kg−1•min−1 which is 89% of predicted. Her VO2 at the anaerobic threshold (AT) of 12.3 mlO2•kg−1•min−1 was likewise within normal limits. However, the patient developed gas exchange evidence of LV dysfunction at a HR of 93 beats/minute as indicated by; 1) a reduced peak O2-pulse that gradually decreased with increasing work rate (figure 2a), 2) an abrupt decrease in ΔVO2/ΔWR slope (Figure 2b) and 3) a steepening of the HR-VO2 uptake slope (Figure 2c). These concurrent changes are characteristic of exercise-induced decreasing stroke volume resulting from myocardial dysfunction caused by ischemia. The ECG revealed isolated premature ventricular beats near peak exercise with no demonstrable ST-segment changes.

Figure 2.

HR: Heart rate, beats per minute

O2-Pulse: Oxygen Pulse, oxygen uptake (ml/min) divided by heart rate (beats per minute)

On the basis of the abnormal physiologic findings, the patient underwent coronary angiography which revealed a > 95% critical stenosis of the right coronary artery. This was treated with intracoronary stent placement.

DISCUSSION

During a progressive, ramped exercise test designed to elicit maximal exertion, cardiac output increases through a synergistic augmentation of both stroke volume and heart rate as external work rate increases. Under normal physiologic conditions, these cardiovascular adaptations will result in a progressively increasing O2-pulse, a linear increase in VO2 vs. WR with a slope of approximately 10 ml/min/watt and a linear increase in HR vs. VO2 to normal peak values. If a patient has obstructive CAD such that the myocardium does not receive sufficient O2 to maintain normal myocardial contraction, the myocardial segments that are rendered ischemic will exhibit abnormal contraction patterns or myocardial dys-synergy (hypokinesis, akinesis or dyskinesis) which can range from mild to severe depending on the extent and magnitude of ischemia. Thus, when myocardial perfusion is reduced producing an O2 supply - O2 demand imbalance, whether from epicardial coronary disease or impaired coronary flow reserve involving the arteriolar resistance vessels, reversible LV dysfunction will result. Thus, CPET quantifies the ischemic work rate threshold. Exceeding the ischemic work rate threshold causes stroke volume to decrease while heart rate increases faster relative to VO2 in partial, but incomplete compensation. Paralleling the failure to maintain a cardiac output increase appropriate for a given increase in work rate is a characteristic flattening or reduction of increase in ΔVO2/ΔWR (Figure 2b), and a decline or lack of progressive increase in O2-pulse (Figure 2a), along with a concomitant steepening of the slope of HR-VO2 uptake relationship (Figure 2c). Since the degree of LV dysfunction detected by CPET is directly proportional to the extent of underlying ischemic burden, severe CAD (such as triple vessel disease) is the most likely form of CAD to be detected by CPET.10

Previous research in this area has focused on the utility of CPET in detecting macrovascular coronary artery disease.11 It is now well-recognized that microvascular CAD, particularly in women, is a significant health care concern.12,13 To better detect this condition, new methods of evaluation must be implemented.14 Peix et al. have previously demonstrated that postmenopausal women with normal coronary angiograms but diagnosed with microvascular coronary artery disease frequently developed LV dysfunction during exercise testing.15 Subjects with either macro- or microvascular CAD may demonstrate a similar CPET response, although nuclear imaging and cardiac catheterization findings may be quite different. Given the potential for CPET to accurately detect LV dysfunction in a non-invasive and cost-effective manner, implementation of this assessment technique in the evaluation of suspected microvascular disease may be clinically advantageous, prompting more appropriate follow-up tests with a high proclivity for microvascular CAD detection, such as magnetic resonance imaging16 and perhaps phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance (31P-NMR) spectroscopy.17

Concomitant gas exchange analysis provides valuable physiologic information that precisely demarcates the HR, VO2 and work-rate at which ischemic LV dysfunction develops. The characteristic changes in O2-pulse, ΔVO2/ΔWR and pattern of HR-VO2 response may, therefore, also be useful in assessing the response to a given therapeutic intervention in a serial fashion, particularly as treatments for myocardial ischemia emerge. Recent evidence that the anatomic definition of angiographic CAD and subsequent PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention) does not inevitably lead to improved outcomes reinforces the need for more precision in characterizing the functional consequences of myocardial ischemia in patients with macrovascular CAD for whom invasive strategies are being considered18. Serial CPET testing has been used to demonstrate normalization of LV function after revascularization in a patient with isolated RCA disease similar to the abnormal response described.19

The use of expired gas analysis is not common practice in the present day clinical exercise laboratory. Future research should continue in this area to more quantifiably determine the value of CPET in diagnosing both macro- and microvascular CAD, assessing responses to therapy and predicting prognosis in CAD. While initial findings are compelling, compilation of additional clinical information and physician education are needed to gain widespread clinical acceptance.

Acknowledgments

From Met-test, there was no funding associated with this paper

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Piepoli MF, Corra U, Agostoni PG, Belardinelli R, Cohen-Solal A, Hambrecht R, Vanhees L. Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure due to left ventricular dysfunction: recommendations for performance and interpretation Part II: How to perform cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:300–311. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piepoli MF, Corra U, Agostoni PG, Belardinelli R, Cohen-Solal A, Hambrecht R, Vanhees L. Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure due to left ventricular dysfunction: recommendations for performance and interpretation. Part I: definition of cardiopulmonary exercise testing parameters for appropriate use in chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:150–164. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000209812.05573.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piepoli MF, Corra U, Agostoni PG, Belardinelli R, Cohen-Solal A, Hambrecht R, Vanhees L. Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure due to left ventricular dysfunction: recommendations for performance and interpretation Part III: Interpretation of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure and future applications. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:485–494. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200602000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whipp BJ, Higgenbotham MB, Cobb FC. Estimating exercise stroke volume from asymptotic oxygen pulse in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:2674–2679. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crisafulli A, Piras F, Chiappori P, Vitelli S, Caria MA, Lobina A, Milia R, Tocco F, Concu A, Melis F. Estimating stroke volume from oxygen pulse during exercise. Physiol Meas. 2007;28:1201–1212. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/10/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchfuhrer MJ, Hansen JE, Robinson TE, Sue DY, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. Optimizing the exercise protocol for cardiopulmonary assessment. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:1558–1564. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.5.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon BK, Kravitz L, Robergs R. VO2max, protocol duration, and the VO2 plateau. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1186–1192. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b13e318054e304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, Stringer W, Whipp B. Clinical Exercise Testing. In: Weinberg A, editor. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation. 4th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:2020–2027. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munhoz EC, Hollanda R, Vargas JP, Silveira CW, Lemos AL, Hollanda RM, Ribeiro JP. Flattening of oxygen pulse during exercise may detect extensive myocardial ischemia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1221–1226. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180601136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belardinelli R, Lacalaprice F, Carle F, Minnucci A, Cianci G, Perna G, D'Eusanio G. Exercise-induced myocardial ischaemia detected by cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1304–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerman A, Sopko G. Women and Cardiovascular Heart Disease: Clinical Implications From the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Are We Smarter? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:S59–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humphries KH, Pu A, Gao M, Carere RG, Pilote L. Angina with "normal" coronary arteries: sex differences in outcomes. Am Heart J. 2008;155:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pries AR, Habazettl H, Ambrosio G, Hansen PR, Kaski JC, Schachinger V, Tillmanns H, Vassalli G, Tritto I, Weis M, de Wit C, Bugiardini R. A review of methods for assessment of coronary microvascular disease in both clinical and experimental settings. Cardiovascular Research. 2008;80:165–174. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peix A, Garcia EJ, Valiente J, Tornes F, Cabrera LO, Cabale B, Carrillo R, Garcia-Barreto D. Ischemia in women with angina and normal coronary angiograms. Coron Artery Dis. 2007;18:361–366. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3281689a3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor AJ, Al-Saadi N, bdel-Aty H, Schulz-Menger J, Messroghli DR, Friedrich MG. Detection of acutely impaired microvascular reperfusion after infarct angioplasty with magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2004;109:2080–2085. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127812.62277.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchthal SD, den Hollander JA, Merz CN, Rogers WJ, Pepine CJ, Reichek N, Sharaf BL, Reis S, Kelsey SF, Pohost GM. Abnormal myocardial phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in women with chest pain but normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:829–835. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boden WE, O'Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL, Chaitman BR, Shaw L, Gosselin G, Nawaz S, Title LM, Gau G, Blaustein AS, Booth DC, Bates ER, Spertus JA, Berman DS, Mancini J, Weintraub WS. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contini M, Andreini D, Agostoni P. Cardiopulmonary exercise test evidence of isolated right coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2006;113:281–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]