Abstract

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) originate from genetically transformed hematopoietic stem cells that retain the capacity for multilineage differentiation and effective myelopoiesis. Beginning in early 2005, a number of novel mutations involving Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), Myeloproliferative Leukemia Virus (MPL), TET oncogene family member 2 (TET2), Additional Sex Combs-Like 1 (ASXL1), Casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene (CBL), Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) and IKAROS family zinc finger 1 (IKZF1) have been described in BCR-ABL1-negative MPNs. However, none of these mutations were MPN specific, displayed mutual exclusivity or could be traced back to a common ancestral clone. JAK2 and MPL mutations appear to exert a phenotype-modifying effect and are distinctly associated with polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis; the corresponding mutational frequencies are ∼99, 55 and 65% for JAK2 and 0, 3 and 10% for MPL mutations. The incidence of TET2, ASXL1, CBL, IDH or IKZF1 mutations in these disorders ranges from 0 to 17% these latter mutations are more common in chronic (TET2, ASXL1, CBL) or juvenile (CBL) myelomonocytic leukemias, mastocytosis (TET2), myelodysplastic syndromes (TET2, ASXL1) and secondary acute myeloid leukemia, including blast-phase MPN (IDH, ASXL1, IKZF1). The functional consequences of MPN-associated mutations include unregulated JAK-STAT (Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription) signaling, epigenetic modulation of transcription and abnormal accumulation of oncoproteins. However, it is not clear as to whether and how these abnormalities contribute to disease initiation, clonal evolution or blastic transformation.

Keywords: polycythemia, thrombocythemia, myelofibrosis, pathogenesis, isocitrate dehydrogenase

Introduction

The WHO (World Health Organization) classification system for hematological malignancies includes eight clinicopathological entities under the category of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs): chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), primary myelofibrosis (PMF), chronic neutrophilic leukemia, chronic eosinophilic leukemia-not otherwise specified, mastocytosis and MPN-unclassifiable.1 Among these, the first four were first assembled in 1951 by William Dameshek,2 as ‘myeloproliferative disorders' accordingly, they are now referred to as ‘classic' MPNs. As CML is invariably and specifically associated with BCR-ABL1, the other three (that is, PV, ET and PMF) are operationally dubbed as ‘BCR-ABL1-negative MPN'.3

PV, ET and PMF are traditionally considered as stem cell-derived monoclonal hemopathies.4, 5, 6 Furthermore, family studies and Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) haplotype analysis have suggested a hereditary component for disease susceptibility.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 The possibility of independently emerging multiple abnormal clones (that is, leading to oligoclonal rather than monoclonal myeloproliferation) has recently been raised and challenges the prevailing concept that considers an ancestral abnormal clone that gives rise to mutually exclusive subclones (Figure 1).15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 In the past 5 years, a number of stem cell-derived19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 mutations involving JAK2 (exon 1427, 28, 29, 30 and exon 12),31 Myeloproliferative Leukemia Virus (MPL) (exon 10),32, 33 TET oncogene family member 2 (TET2) (across several exons),25 Additional Sex Combs-Like 1 (ASXL1) (exon 12),26 Casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene (CBL) (exons 8 and 9),34 Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) (exon 4),35, 36 IDH2 (exon 4)35, 37 and IKAROS family zinc finger 1 (IKZF1) (deletion of several exons) have been described in chronic- or blast-phase MPN and are discussed in this review (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Clonal origination and evolution in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). PV, polycythemia vera; ET, essential thrombocythemia; PMF, primary myelofibrosis; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; MPL, thrombopoietin receptor; TET2, TET oncogene family member 2; ASXL1, Additional Sex Combs-Like 1; CBL, Casitas B-lineage Lymphoma proto-oncogene; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; IKZF1, IKAROS family zink finger 1.

Table 1. Novel mutations in polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), primary myelofibrosis (PMF) and blast-phase myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN).

| Mutations | Chromosome location | Mutational frequency | Pathogenetic relevance | Prognostic relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAK2V617F exon 14 (Janus kinase 2) | 9p24 | PV∼96% | Believed to contribute to myeloproliferation and progenitor cell growth factor hypersensitivity | Limited |

| ET∼55% | ||||

| PMF∼65% | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼50% | ||||

| JAK2 exon 12 | 9p24 | PV∼3% | Believed to contribute to primarily erythroid myeloproliferation | Not enough information |

| ET∼rare | ||||

| PMF∼rare | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼? | ||||

| MPL exon 10 (Myeloproliferative Leukemia Virus oncogene) (encodes for thrombopoietin receptor) | 1p34 | PV∼rare | Believed to contribute to primarily megakaryocytic myeloproliferation | Not enough information |

| ET∼3% | ||||

| PMF∼10% | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼? | ||||

| TET2 mutations occur across several of the gene's 12 exons (TET oncogene family member 2) | 4q24 | PV∼16% | Might contribute to epigenetic modulation of transcription (TET1 catalyzes conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine) | Not enough information |

| ET∼5% | ||||

| PMF∼17% | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼17% | ||||

| ASXL1 exon 12 (Additional Sex Combs-Like 1) | 20q11.1 | PV∼? | Believed to affect regulation of transcription and RAR-mediated signaling | Not enough information |

| ET∼? | ||||

| PMF∼? | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼19% | ||||

| CBL exons 8 and 9 (Casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene) | 11q23.3 | PV∼rare ET∼rare | Believed to alter the regulatory function of wild-type CBL against kinase signaling because of defective ubiquitylation of oncoproteins | Not enough information |

| PMF∼6% | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼? | ||||

| IDH1/IDH2 exon 4/exon 4 (Isocitrate dehydrogenase) | 2q33.3/15q26.1 | PV∼rare | Induces accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate, a possible oncoprotein | Not enough information |

| ET∼rare | ||||

| PMF∼4% | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼20% | ||||

| IKZF1 (IKAROS family zink finger 1) | 7p12 | PV∼rare | Believed to alter tumor suppressor activity of the wild-type protein | Not enough information |

| ET∼rare | ||||

| PMF∼rare | ||||

| Blast-phase MPN∼19% |

Abbreviation: RAR, retinoic acid receptor.

JAK2 mutations

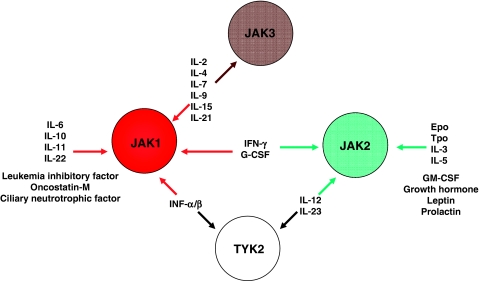

JAK2 is located on chromosome 9p24 and includes 25 exons and its protein 1132 amino acids. JAK2 is one of the four Janus family nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases; JAK1, JAK2 and TYK2 are ubiquitously expressed in mammalian cells, whereas JAK3 expression is limited to hematopoietic cells. Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling is important for a wide spectrum of cellular processes, including proliferation, survival or normal functioning of hematopoietic, immune, cardiac and other cells.38, 39 JAKs transduce signals from their cognate type I and type II nonkinase cytokine receptors. Selective association of a JAK family member with specific cytokines or growth factors might explain some of the differences in therapeutic and side-effect profiles among drugs that primarily target JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 or multiple JAKs (Figure 2).39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44

Figure 2.

The spectrum of cytokines and growth factors that use Janus kinases (JAKs) for signal transduction.

JAK2V617F

Oncogenic JAK1, JAK2 and JAK3 mutations have been associated with both lymphoid and myeloid neoplasms.45 Of particular relevance to MPN, JAK2V617F was discovered in 200427 and the first reports appeared in early 2005.27, 28, 29, 30 JAK2V617F is by far the most prevalent mutation in BCR-ABL1-negative MPN (occurs in ∼95% of patients with PV, in ∼55% with ET and in ∼65% with PMF),45 but it is also seen in some patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/MPN (for example, refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis)46, 47, 48 and, rarely, in primary acute myeloid leukemia (AML), MDS or CML.49, 50, 51, 52 However, this should not undermine its broad specificity to patients with myeloid neoplasms (including those with occult disease and splanchnic vein thrombosis)53, 54 and the fact that the mutation is not seen in patients with lymphoid neoplasms, reactive myeloproliferation or in healthy volunteers.55, 56, 57, 58

JAK2V617F results from a somatic G to T mutation involving JAK2 exon 14, which leads to nucleotide change at position 1849 and the substitution of valine to phenylalanine at codon 617.59 The mutation affects the noncatalytic ‘pseudo-kinase' domain and is believed to derail its kinase-regulatory activity. JAK2V617F-mediated transformation is believed to require coexpression of type I cytokine receptor and leads to STAT5/3 activation;60, 61, 62, 63 in addition, a recent study has suggested an epigenetic effect through nuclear translocation of the mutant molecule and direct phosphorylation of histone H3.62 Such a noncanonical mode of action has previously been reported to disrupt heterochromatin-mediated tumor suppression in Drosophila.64 Some patients with MPN might carry multiple JAK2 mutations, sometimes occurring in the same exon and in cis configuration.65 Such events might have functional relevance as they might alter specific signaling.

JAK2V617F induces PV-like phenotype in mouse transplantation models,27 and this observation has been further confirmed by a recent report of an inducible JAK2V617F knock-in mouse model, in which both heterozygous and homozygous mutation expressions induced PV-like disease, with the latter causing a more aggressive phenotype with myelofibrosis.66 Such experimental data along with the fact that virtually all patients with PV carry a JAK2 mutation,67 suggest a cause–effect relationship with erythrocytosis.31, 68, 69, 70, 71 Somewhat consistent with this contention, JAK2V617F homozygosity is infrequent in ET and its frequent occurrence in PV has been ascribed to mitotic recombination, possibly facilitated by JAK2V617F-induced genetic instability.72 However, both ET- and PMF-like disease are also induced in mice by experimental manipulation of the JAK2V617F allele burden,73, 74 and mutant allele burden in PMF is often as high as that seen in PV and its level increases further during fibrotic transformation.75 These observations suggest the presence of additional phenotype determinants in primary and post-PV/ET MF.

Despite the above-described experimental and clinical observations, JAK2V617F does not appear to be the disease-initiating event and probably defines an MPN subclone, which does not always account for leukemic transformation.18, 76, 77 In the latter regard, JAK2V617F-positive, as opposed to JAK2V617F-negative, blast-phase MPN might require a fibrotic phase disease transition.18 On the other hand, JAK2 wild-type AML that develops in the setting of JAK2V617F-positive MPN does not necessarily arise from originally mutation-positive clones that have undergone mitotic recombination of wild-type JAK2.18 The complexity of clonal hierarchy and structure in MPN has become more evident with recent demonstrations of multiple mutations occurring in the same patient and the fact that such mutations are neither necessarily mutually exclusive nor follow a predictable sequence of occurrence.16, 36, 78

JAK2V617F-positive MPN has been associated with older age at diagnosis (ET and PMF), higher hemoglobin level (ET and PMF), leukocytosis (ET and PMF) and lower platelet count (ET).75 A higher mutant allele burden has been associated with pruritus (PV and PMF), higher hemoglobin level (PV), leukocytosis (PV, ET and PMF) and larger spleen size (PV, ET and PMF).79, 80, 81, 82, 83 However, save for some contrary observations,80, 84 the mere presence of JAK2V617F or increased mutant allele burden does not seem to affect survival or leukemic transformation.83, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 Instead, a lower mutant allele burden has been associated with inferior survival in PMF.80, 84 This particular finding illustrates prognostically relevant clonal complexity in PMF. JAK2V617F allele burden increases with time in PV and PMF,80, 82, 91 but not in ET.83 This phenomenon in PV and PMF coincides with the development of post-PV myelofibrosis, marked splenomegaly and requirement for chemotherapy.79, 90, 92, 93 Current evidence is not conclusive with regard to the relationship between JAK2V617F and thrombosis.82, 83, 85, 86, 93, 94, 95

JAK2 exon 12 mutations

JAK2 exon 12 mutations are relatively specific to JAK2V617F-negative PV and were first described in 2007.31 Subsequent studies have identified N542-E543del as the most frequent among the >10 JAK2 exon 12 mutations described so far.31, 68, 69, 96 JAK2 exon 12 mutations include in-frame deletions, point mutations and duplications, mostly affecting seven highly conserved amino-acid residues (F537–E543). As is the case with its exon 14 counterpart (that is, JAK2V617F), the JAK2K539L exon 12 mutation has also been shown to induce erythrocytosis in mice.31 JAK2 exon 12 mutation-positive PV patients are often heterozygous for the mutation and are characterized by predominantly erythroid myelopoiesis, subnormal serum erythropoietin level and younger age at diagnosis.31, 97, 98 The clinical course of these patients seems to be similar to that of patients with JAK2V617F-positive PV.68, 98, 99

MPL mutations

MPL, located on chromosome 1p34, includes 12 exons and encodes for the thrombopoietin receptor (635–680 amino acids). MPL is the key growth and survival factor for megakaryocytes. Gain-of-function germline MPL mutations have been associated with familial thrombocytosis (S505N) that is, interestingly, associated with an MPN phenotype, including splenomegaly, myelofibrosis and an increased risk of thrombosis.100 The particular observation further attests to the phenotype-modifying effect of somatic MPL mutations in MPN. An MPL single-nucleotide polymorphism (G1238T) that results in a K39N substitution is found in ∼7% of African Americans and is associated with higher platelet counts.101

Somatic MPL mutations are rare and their occurrence is largely limited to patients with MPN, although their occurrence in acute megakaryocytic leukemic patients has also been reported.102 MPLW515L results from a G to T transition at nucleotide 1544 (exon 10), resulting in a tryptophan to leucine substitution at codon 515. MPLW515L was first described in 2006 among patients with JAK2V617F-negative PMF and induces a PMF-like disease with thrombocytosis in mice.32 Subsequently, MPLW515K and other exon 10 MPL mutations (such as MPLW515S and MPLS505N) were described in ET and PMF with mutational frequencies that range from 3 to 15%.32, 33, 103, 104, 105, 106 MPLW515L is the most frequent MPN-associated MPL mutation, whereas MPLS505N also occurs in the setting of hereditary thrombocythemia, as mentioned above.100

As is the case with JAK2 mutations, MPL515 mutations are stem cell-derived events that involve both myeloid and lymphoid progenitors.24, 33, 107 MPL mutant-induced oncogenesis also results in constitutive JAK-STAT activation and might require specific MPL mutant variants (such as MPLW515)108 and receptor residues (such as Y112).109 Some patients with ET or PMF display multiple MPL mutations and others a low allele burden JAK2V617F clone together with a higher allele burden MPL mutation.104, 110 Homozygosity for MPL mutations is also ascribed to acquired uniparental disomy, as is the case with JAK2V617F.111

MPL-mutated ET has been associated with older age, lower hemoglobin level, higher platelet count, microvascular symptoms and a higher risk of post-diagnosis arterial thrombosis.106, 112 The presence of MPL mutation did not appear to affect survival, fibrotic or leukemic transformation.106 MPL-mutated PMF has been associated with the female gender, older age, lower hemoglobin level and a higher likelihood of becoming transfusion dependent.105 This set of findings suggests a phenotype-modifying effect that is different from that seen with a JAK2 mutation.

TET2 mutations

TET2 is one of three homologous human proteins (that is, TET1, TET2 and TET3) the function of which, based on a recent report on TET1,113 might include conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, and thus possibly affect the epigenetic regulation of transcription. TET1 was the first of the three TET genes to be described and the name is derived from ‘ten–eleven translocation 1'—a name given to a novel gene located at chromosome 10q22 and was identified as the fusion partner of MLL during an AML-associated chromosomal translocation, t(10;11)(q22;q23).114 TET2 is located on chromosome 4q24, which is a breakpoint that is also involved in other AML-associated translocations, including t(3;4)(q26;q24), t(4;5)(q24;p16), t(4;7)(q24;q21) and del(4)(q23q24).115 TET2 has multiple isoforms and isoform A, which is affected by most of the TET2 mutations described so far, and includes 12 exons. TET3 is located at 2p13.1.

TET2 mutations, first described in 2008,25 include frameshift, nonsense and missense mutations, scattered across several of its 12 exons, and are seen in both JAK2V617F-positive (17%) and JAK2V617F-negative (7%) MPNs with approximate mutational frequencies of 16% in PV, 5% in ET, 17% in PMF, 14% in post-PV MF, 14% in post-ET MF and 17% in blast-phase MPN.116 Higher incidences of TET2 mutations have been reported in systemic mastocytosis, MPN-unclassifiable, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), MDS, MDS/MPN, AML and idic(X)(q13)-positive myeloid malignancies;117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124 in addition, a germline TET2 mutation was recently described in a patient with PV.16 Furthermore, TET2 mutations have been shown to coexist with other pathogenetically relevant mutations involving RARA, MPL, KIT, FLT3, RAS, MLL, CEBPA or NPM1.117, 118, 119, 120 TET2 mutations in MPN can either antedate or follow the acquisition of a JAK2 mutation (exon 12 or 14), or occur in an independent manner leading to a biclonal pattern.16, 18, 25

Taken together, the ubiquitous nature of TET2 mutations undermines their specific pathogenetic contribution to MPN. Furthermore, the presence of the mutant TET2 did not seem to affect survival, leukemic transformation, thrombosis risk or cytogenetic profile in either PV or PMF.116, 125, 126, 127 By contrast, the presence of TET2 mutations was associated with superior survival in MDS121 and inferior survival in AML120 and CMML.128 A further twist in the TET2 story was recently reported by a study that suggested the possible acquisition of the mutation during leukemic transformation of MPN;36 a paired sample analysis in 14 patients disclosed the absence of TET2 mutations in chronic-phase disease but their presence in 5 cases during blast-phase disease, regardless of JAK2V617F mutational status. However, these results were not reproduced by two other studies that looked for the presence of TET2 mutations in patient samples obtained during chronic- and blast-phase diseases.126, 129 One of the latter studies also showed that post-MPN AML can develop in the presence or absence of TET2 or JAK2 mutations in a mutually exclusive manner or not.129

ASXL1 mutations

ASXL1 (includes 12 or 13 exons) maps to chromosome 20q11.1 and belongs to the Enhancer of trithorax and Polycomb gene family. Gene function is believed to include dual activator/suppressor activity toward transcription and includes repression of retinoic acid receptor-mediated transcription.130 ASXL1 is expressed in most hematopoietic cell types, and a knockout mouse model displayed mild defects in myelopoiesis but did not develop MDS or other hematological malignancy.131 PAX5-ASXL1 has been associated with the B precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia.132 Truncation exon 12 mutations, which affect the C-terminal PHD (plant homeodomain), have recently (2009) been described in 11% of patients with MDS, 43% of those with CMML, 7% with primary and 47% with secondary AML.133, 134 In a more recent study of 300 patients with a spectrum of non-MPN myeloid malignancies, ASXL1 mutations were found in 62 patients (∼21%): ∼7% in MDS without excess blasts, 11–17% in MDS with ring sideroblasts, 31% in MDS with excess blasts, 23% in post-MDS AML, 33% in CMML and 30% in primary AML. ASXL1 mutations might be more common in patients with normal karyotype or −7/7q− and infrequent in the presence of −5/5q−. In AML with normal karyotype, ASXL1 mutations were often absent in patients with NPM1 or FLT3 mutations; mutational frequency was 34% in non-NPM1 cases.134

ASXL1 mutations occur in both chronic- and blast-phase MPNs;26, 36 in a study of 64 patients with ET (n=35), PMF (n=11), PV (n=10), blast-phase MPN (n=5) and MPN-unclassifiable (n=3), heterozygous mutations of ASXL1 were identified in 5 cases who were all JAK2V617F negative (∼8% 3 PMF, 1 ET and 1 blast-phase ET).26 In an even more recent study of 63 patients with post-MPN AML, ASXL1 mutations were seen in 12 (19%) cases and did not appear to be acquired during leukemic transformation.36 ASXL1 mutations in the latter study were shown to coexist with JAK2 or TET2 but not IDH1 mutations and, in some instances, appeared to predate the acquisition of both JAK2 and TET2 mutations.36 Obviously, larger studies are required to confirm these findings and determine prognostic impact, especially in terms of leukemic transformation risk. Similarly, additional laboratory studies are required to clarify ASXL1 mutation-mediated oncogenesis and whether it involves loss of tumor suppression or aberrant retinoic acid receptor signaling.

CBL mutations

CBL (includes 16 exons) is located at 11q23.3, telomeric to MLL and encodes for a cytosolic protein capable of dual function: negative regulation of kinase signaling mediated by E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and an adaptor protein function with a positive effect on downstream signaling.135 CBL (906 amino acids) is one of three cytosolic CBL family of proteins (CBL, CBL-B and CBL-C/3) and its N terminal features tyrosine kinase-binding and zinc-binding RING-finger domains with a linker domain between them, and its C terminal is composed of a proline-rich region. E3 ubiquitin ligase activity is central to the primary function of CBL, which is the downregulation of activated receptor and nonreceptor protein-tyrosine kinases by ubiquitination, internalization and lysosomal/proteosomal degradation.

Of relevance to myeloid neoplasms, wild-type CBL has been shown to participate in the ubiquitination of MPL,136 KIT137 and FLT3,138 and ubiquitylation of the latter two proteins was shown to be defective in the presence of mutant CBL.137, 138 Mutant CBL induces oncogenic phenotype in various cell lines and promotes growth factor independence.139 CBL knockout mice display expanded hematopoietic stem cell pool, splenomegaly and enhanced growth factor sensitivity of hematopoietic progenitor cells.139 Retroviral expression of mutant CBL in transplanted bone marrow induced extensive and diffuse multiorgan infiltration by mast cells accompanied by mast cell sarcoma, myeloproliferative phenotype and acute leukemia in some instances.137 In contrast to this observation, CBL mutations were not detected in any of the 60 patients with systemic mastocytosis.34

CBL mutations in myeloid malignancies are usually associated with 11q acquired uniparental disomy139 and were first recognized in AML as an MLL–CBL fusion resulting from interstitial CBL deletion.140 Subsequent studies have shown that CBL mutations were most frequent in juvenile monomyelocytic leukemia (JMML) and CMML. In one large study,141 mostly exon 8 CBL mutations were detected in 27 (17%) of 159 cases with JMML (40% mutational frequency among patients without known RAS pathway mutations) and 5 (11%) of 44 patients with CMML.141 The respective mutational frequencies for JMML and CMML, from another group of investigators, were 10 and 5%.142, 143 Others have also shown relatively high CBL mutation rates in CMML (13–15%)34, 139 and one of the latter studies reported an 8% incidence in BCR-ABL1-negative atypical CML.34 It is to be recalled that CMML, JMML and atypical CML are all subcategories of MDS/MPN.144 By contrast, CBL mutations were infrequent in refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis (0 of 19 analyzed cases), a provisional MDS/MPN entity.145

Most CBL mutations in JMML are homozygous, which suggests a tumor-suppressor function for the normal protein. This conjecture is supported by the observation that two patients with homozygous mutations in their hematopoietic cells displayed germline heterozygous mutations in their buccal or cord blood cells.141 In general, CBL mutations associated with JMML and CMML consist of missense substitutions or in-frame deletions and are located throughout the linker and RING-finger domain. JMML patients with mutant CBL do not express RAS or PTPN11 mutations but display similar biochemical (for example, cellular granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor hypersensitivity) and clinical features.141, 143 By contrast, mutant CBL has been shown to coexist with mutations involving RUNX1, FLT3, JAK2 and TP53.139, 141

CBL mutations are infrequent in myeloid malignancies other than JMML or CMML. In a recent study of 577 patients with MPN or MDS/MPN, including 74 patients with PV, 24 with ET and 53 with PMF, CBL mutations in either exon 8 or 9 were identified in 3 (6%) patients with PMF and 1 of 96 patients with CEL/HES (chronic eosinophilic leukemia/hypereosinophilic syndrome).34 CBL mutations were found in <1% of patients with primary AML, MDS, systemic mastocytosis, CNL (chronic neutrophilic leukemia), blast-phase CML and T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia.34, 139, 142, 146 Mutational frequency might be higher in post-MDS/MPN AML142 or in AML with core-binding factor or 11q aberrations.146, 147 Acquisition of mutant CBL during disease progression from ET to post-ET MF was documented in one instance.34 Additional studies are required to clarify the pathogenetic contribution of altered CBL to PMF or post-ET/PV MF and its potential role in fibrotic or leukemic disease transformation.

IDH mutations

IDH1 (located on chromosome 2q33.3; includes 10 exons) and IDH2 (located on chromosome 15q26.1; includes 11 exons) encode for isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2, respectively, which are homodimeric NADP+-dependent enzymes that catalyze oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate, generating NADPH from NADP+. IDH1 and IDH2 are different from the mitochondrial NAD+-dependent IDH3-α, IDH3-β and IDH3-γ. IDH1 (414 amino acids) is localized in the cytoplasm and peroxisomes, whereas IDH2 (452 amino acids) is localized in the mitochondria. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations were first described in gliomas148 and subsequently in AML149, 150, 151 and are infrequently seen in other tumors.152, 153, 154, 155 These mutations were all heterozygous and affected three specific arginine residues: R132 (IDH1), R172 (the IDH1 R132 analogous residue on IDH2) and R140 (IDH2). Functional characterization suggests a loss of activity toward isocitrate (that is, the mutant wild-type heterodimer has decreased affinity to isocitrate) and gain of function in catalyzing NADPH-dependent reduction of α-ketoglutarate to the (R) enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate; the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α pathway also appears to be activated.156, 157 Excess accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate has been demonstrated in both glioma and AML with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations.150, 151, 156

IDH1 (exon 4 affecting R132) and IDH2 (exon 4 affecting R172) mutations are mutually exclusive and occur in >70% and <1%, respectively, of patients with WHO grade II or III histology and secondary glioblastomas but are infrequently (<5% incidence) seen in primary glioblastoma.158, 159, 160, 161 In one study of 496 gliomas, >90% of the IDH1 mutations were IDH1R132H.162 Paired sample analysis in glioma patients transforming from low- to high-grade histology showed that IDH mutations were early events. IDH-mutated glioma patients are younger and display better survival and often express TP53 but not PTEN, EGFR, CDKN2 or CDKN2B mutations.158, 161, 163 The superior survival associated with IDH mutations has been attributed to increased sensitivity to treatment, as a result of decreased NADPH production, and, therefore, reduced risk of progression.164, 165, 166

The first study on IDH mutations in AML included 188 patients with primary AML and reported IDH1 but not IDH2 mutations in 16 (∼9%) cases: R132C in 8, R132H in 7 and R132S in 1.149 In a subsequent AML study of 493 adult Chinese patients,167 27 (∼6%) expressed IDH1 mutations (37% R132C, 26% R132H, 19% R132S, 15% R132G and 4% R132L). In both studies, IDH1 mutations clustered with normal karyotype, NPM1 mutations and trisomy 8. More recently, IDH2 exon 4 mutations, affecting R172 or R140, were also shown to occur in primary AML.150, 151 In one of these studies, 18 (23%) of 78 patients displayed either IDH1 (n=6; ∼8%) or IDH2 (n=12; ∼15% 7 R140Q and 5 R172K) mutations.150 AML patients with IDH2 mutations were also less likely to carry FLT3, NPM1 or ASXL1 mutations,150 whereas the above-mentioned study from China167 reported the coexistence of IDH1 mutations and RUNX1, PTPN11, NRAS, FLT3-ITD, FLT3-TKD or MLL-PTD mutations.150, 167 In general, survival in primary AML did not seem to be affected by the presence of IDH mutations.149, 150, 167

IDH mutations have also been described in post-MPN AML.35, 36, 37 In one such study, IDH1 mutations were seen in ∼8% (5 of 63) of patients, mostly occurring in the absence of TET2 and ASXL1 mutations.36 In this particular study, there was not significant difference in IDH1 mutational frequency between post-MPN AML, post-MDS AML and primary AML. Furthermore, paired sample analysis did not suggest acquisition of IDH1 mutation during leukemic transformation.36 In another study of AML occurring in the setting of JAK2-mutated MPN,35 mutant IDH was seen in 5 (31%) of 16 patients: 3 R132C (1 post-PMF, 1 post-ET and 1 post-PV with exon 12 mutation) and 2 R140Q (1 post-PMF with trisomy 8 and 7q− and 1 post-PV with complex karyotype). Three patients lost their mutant JAK2 at the time leukemic transformation; in two of these three patients, the IDH mutation was present in leukemic blasts with wild-type JAK2 but absent from JAK2 mutation-positive progenitor colonies. By contrast, in the PMF patient with IDH2R140Q, the mutation was detected in both JAK2V617F-positive erythroid colonies and leukemic blasts. The authors did not find IDH mutations in 180 patients with either PV or ET.35

Most recently, 200 patients with either chronic- or blast-phase MPN were screened for IDH1 and IDH2 mutations.37 A total of nine IDH mutations including five IDH1 and four IDH2 were found and mutational frequencies were ∼21% for blast-phase MPN and ∼4% for PMF. No mutations were seen in PV or ET. Furthermore, IDH mutations were found in only 1 of 12 paired chronic- and blast-phase samples and the mutation was detected in both chronic- and blast-phase disease samples in the single IDH-mutated case. The specific IDH1 mutations found in this study included R132C and R132S and the IDH2 mutations R140Q and R140W. IDH mutations coexisted with JAK2V617F. The results of this and the aforementioned study suggest that IDH mutations are relatively frequent in blast- but not chronic-phase MPN, but more studies are required to find out whether they represent early genetic events or are acquired during leukemic transformation.

IKZF1 mutations

IKAROS family zinc finger 1 (IKZF1; 7p12) encodes for Ikaros transcription factors, which are important regulators of lymphoid differentiation. IKZF1 gene (seven translated exons) transcription is characterized by multiple alternatively spliced transcripts with common C- (inter-Ikaros protein dimerization) and N-terminal (DNA-binding) domains. IKZF1 is believed to modulate expression of lineage-specific genes through a mechanism that involves chromatin remodeling and results in effective lymphoid development and tumor suppression. Loss-of-function animal models develop severe B, T and NK cell defects (homozygous gene deletions) or lymphoblastic leukemia (heterozygous for a dominant-negative allele).169 IKZF1 mutations and overexpression of dominant-negative isoforms are prevalent in ALL, including blast-phase CML or BCR-ABL1-positive ALL, suggesting a pathogenetic contribution to leukemic transformation.170 A recent study demonstrated that IKZF1 deletions were rare in chronic-phase MPN but were detected in approximately 19% of patients with blast-phase MPN.171 The occurrence of IKZF1 mutations in MPN is particularly relevant, as part of their functional consequence might include JAK–STAT activation.

Concluding remarks

PMF–PV–ET were first described in 1879–1892–1934 and their close relationship was formally recognized in 1951 and molecularly validated in 2005.2 Unlike CML, pathogenetic mechanisms in these BCR-ABL1-negative MPN are turning out to be more complex than originally believed, and their trademark JAK2 and MPL mutations do not appear to be analogous to BCR-ABL1 in terms of their importance as therapeutic targets.41, 78 The repertoire of other mutations (such as TET2, ASXL1, CBL, IDH mutations) in MPN is growing but their specific pathogenetic relevance is undermined by their omnipresence in other myeloid malignancies. Conversely, the particular scenario might reflect our collective oversight regarding the molecular inter-relationship among phenotypically disparate myeloid malignancies. Regardless, on the basis of the assumption that JAK-STAT is central to the pathogenesis of BCR-ABL1-negative MPN,27, 31, 32, 68, 69, 105, 112 a number of orally administered anti-JAK2 ATP mimetics have been developed and are undergoing clinical trials.42, 43, 44 So far, the two that have shown the most promising clinical activity are TG101348 (JAK2 inhibitor) and INCB018424 (JAK1/2 inhibitor).41 Other drugs that are currently in clinical trials for PMF, PV or ET include other kinase inhibitors (such as CYT387, CEP-701, AZD1480, SB1518, erlotinib), histone deacetylase inhibitors (such as ITF2357, MK-0683, panobinostat) and the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody bevacizumab (http://ClinicalTrials.gov).42, 168

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A. The history of myeloproliferative disorders: before and after Dameshek. Leukemia. 2008;22:3–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Classification and diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 2008 World Health Organization criteria and point-of-care diagnostic algorithms. Leukemia. 2008;22:14–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson JW, Fialkow PJ, Murphy S, Prchal JF, Steinmann L. Polycythemia vera: stem-cell and probable clonal origin of the disease. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:913–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197610212951702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fialkow PJ, Faguet GB, Jacobson RJ, Vaidya K, Murphy S. Evidence that essential thrombocythemia is a clonal disorder with origin in a multipotent stem cell. Blood. 1981;58:916–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson RJ, Salo A, Fialkow PJ. Agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: a clonal proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells with secondary myelofibrosis. Blood. 1978;51:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgren O, Goldin LR, Kristinsson SY, Helgadottir EA, Samuelsson J, Bjorkholm M. Increased risks of polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis among 24 577 first-degree relatives of 11 039 patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms in Sweden. Blood. 2008;112:2199–2204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Fridley BL, Lasho TL, Gilliland DG, Tefferi A. Host genetic variation contributes to phenotypic diversity in myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2008;111:2785–2789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcaydu D, Skoda RC, Looser R, Li S, Cazzola M, Pietra D, et al. The ‘GGCC' haplotype of JAK2 confers susceptibility to JAK2 exon 12 mutation-positive polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2009;23:1924–1926. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcaydu D, Harutyunyan A, Jager R, Berg T, Gisslinger B, Pabinger I, et al. A common JAK2 haplotype confers susceptibility to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet. 2009;41:450–454. doi: 10.1038/ng.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AV, Chase A, Silver RT, Oscier D, Zoi K, Wang YL, et al. JAK2 haplotype is a major risk factor for the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet. 2009;41:446–449. doi: 10.1038/ng.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik MM, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Gangat N, Caramazza D, Siragusa S, et al. MPL mutation effect on JAK2 46/1 haplotype frequency in JAK2V617F-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms Leukemia 2010(e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Patnaik MM, Finke CM, Hussein K, Hogan WJ, et al. JAK2 germline genetic variation affects disease susceptibility in primary myelofibrosis regardless of V617F mutational status: nullizygosity for the JAK2 46/1 haplotype is associated with inferior survival. Leukemia. 2010;24:105–109. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Gangat N, Wolanskyj AP, Hanson CA, et al. The JAK2 46/1 haplotype confers susceptibility to essential thrombocythemia regardless of JAK2V617F mutational status-clinical correlates in a study of 226 consecutive patients. Leukemia. 2010;24:110–114. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JR, Everington T, Linch DC, Gale RE. In essential thrombocythemia, multiple JAK2-V617F clones are present in most mutant-positive patients: a new disease paradigm. Blood. 2009;114:3018–3023. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub FX, Looser R, Li S, Hao-Shen H, Lehmann T, Tichelli A, et al. Clonal analysis of TET2 and JAK2 mutations suggests that TET2 can be a late event in the progression of myeloproliferative neoplasms Blood 20101152003–2007.blood-2009-2009-245381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub FX, Jager R, Looser R, Hao-Shen H, Hermouet S, Girodon F, et al. Clonal analysis of deletions on chromosome 20q and JAK2-V617F in MPD suggests that del20q acts independently and is not one of the predisposing mutations for JAK2-V617F. Blood. 2009;113:2022–2027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-167056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer PA, Delhommeau F, Lecouedic JP, Dawson MA, Chen E, Bareford D, et al. Two routes to leukemic transformation following a JAK2 mutation-positive myeloproliferative neoplasm Blood 2009(e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- James C, Mazurier F, Dupont S, Chaligne R, Lamrissi-Garcia I, Tulliez M, et al. The hematopoietic stem cell compartment of JAK2V617F-positive myeloproliferative disorders is a reflection of disease heterogeneity. Blood. 2008;112:2429–2438. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralovics R, Teo SS, Li S, Theocharides A, Buser AS, Tichelli A, et al. Acquisition of the V617F mutation of JAK2 is a late genetic event in a subset of patients with myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2006;108:1377–1380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-009605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer PA, Jones AV, Bench AJ, Goday-Fernandez A, Boyd EM, Vaghela KJ, et al. Clonal diversity in the myeloproliferative neoplasms: independent origins of genetically distinct clones. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:904–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeno H, Levine RL, Gilliland DG, Michor F. A progenitor cell origin of myeloid malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16616–16621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908107106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Finke C, Mesa RA, Hogan WJ, Ketterling RP, et al. Extending Jak2V617F and MplW515 mutation analysis to single hematopoietic colonies and B and T lymphocytes. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2358–2362. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Finke C, Markovic SN, Tefferi A. Demonstration of MPLW515K, but not JAK2V617F, in in vitro expanded CD4+ T lymphocytes. Leukemia. 2007;21:2206–2207. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, James C, Trannoy S, Masse A, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2289–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbuccia N, Murati A, Trouplin V, Brecqueville M, Adelaide J, Rey J, et al. Mutations of ASXL1 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2009;23:2183–2186. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C, Ugo V, Le Couedic JP, Staerk J, Delhommeau F, Lacout C, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434:1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, Teo SS, Tiedt R, Passweg JR, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, Ebert BL, Wernig G, Huntly BJ, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365:1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LM, Tong W, Levine RL, Scott MA, Beer PA, Stratton MR, et al. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:459–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikman Y, Lee BH, Mercher T, McDowell E, Ebert BL, Gozo M, et al. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani AD, Levine RL, Lasho T, Pikman Y, Mesa RA, Wadleigh M, et al. MPL515 mutations in myeloproliferative and other myeloid disorders: a study of 1182 patients. Blood. 2006;108:3472–3476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grand FH, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Ernst T, Zoi K, Zoi C, McGuire C, et al. Frequent CBL mutations associated with 11q acquired uniparental disomy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2009;113:6182–6192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Beer P. Somatic mutations of IDH1 and IDH2 in the leukemic transformation of myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:369–370. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0910063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Wahab O, Manshouri T, Patel J, Harris K, Yao J, Hedvat C, et al. Genetic analysis of transforming events that convert chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms to leukemias. Cancer Res. 2010;70:447–452. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Lasho T, Finke C, Mai M, McClure R, Tefferi A.IDH1 and IDH2 mutation analysis in chronic and blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasms Leukemia 2010. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kurdi M, Booz GW. JAK redux: a second look at the regulation and role of JAKs in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1545–H1556. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00032.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O'Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway: input and output integration. J Immunol. 2007;178:2623–2629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A. JAK2 inhibitor therapy in myeloproliferative disorders: rationale, preclinical studies and ongoing clinical trials. Leukemia. 2008;22:23–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Lasho T, Smith G, Burns CJ, Fantino E, Tefferi A. CYT387, a selective JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor: in vitro assessment of kinase selectivity and preclinical studies using cell lines and primary cells from polycythemia vera patients. Leukemia. 2009;23:1441–1445. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Hood J, Lasho T, Levine RL, Martin MB, Noronha G, et al. TG101209, a small molecule JAK2-selective kinase inhibitor potently inhibits myeloproliferative disorder-associated JAK2V617F and MPLW515L/K mutations. Leukemia. 2007;21:1658–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasho TL, Tefferi A, Hood JD, Verstovsek S, Gilliland DG, Pardanani A. TG101348, a JAK2-selective antagonist, inhibits primary hematopoietic cells derived from myeloproliferative disorder patients with JAK2V617F, MPLW515K or JAK2 exon 12 mutations as well as mutation negative patients. Leukemia. 2008;22:1790–1792. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A. Molecular drug targets in myeloproliferative neoplasms: mutant ABL1, JAK2, MPL, KIT, PDGFRA, PDGFRB and FGFR1. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:215–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renneville A, Quesnel B, Charpentier A, Terriou L, Crinquette A, Lai JL, et al. High occurrence of JAK2 V617 mutation in refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts associated with marked thrombocytosis. Leukemia. 2006;20:2067–2070. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt-Graeff AH, Teo SS, Olschewski M, Schaub F, Haxelmans S, Kirn A, et al. JAK2V617F mutation status identifies subtypes of refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts associated with marked thrombocytosis. Haematologica. 2008;93:34–40. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah E, Nussenzveig R, Yin CC, Bueso-Ramos C, Tam C, Manshouri T, et al. Prognostic interaction between thrombocytosis and JAK2 V617F mutation in the WHO subcategories of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative disease-unclassifiable and refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts and marked thrombocytosis. Leukemia. 2008;22:1295–1298. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensma DP, McClure RF, Karp JE, Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Powell HL, et al. JAK2 V617F is a rare finding in de novo acute myeloid leukemia, but STAT3 activation is common and remains unexplained. Leukemia. 2006;20:971–978. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensma DP, Dewald GW, Lasho TL, Powell HL, McClure RF, Levine RL, et al. The JAK2 V617F activating tyrosine kinase mutation is an infrequent event in both ‘atypical' myeloproliferative disorders and myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2005;106:1207–1209. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inami M, Yamaguchi H, Hasegawa S, Mitamura Y, Kosaka F, Kobayashi A, et al. Analysis of the exon 12 and 14 mutations of the JAK2 gene in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:216. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein K, Bock O, Theophile K, Seegers A, Arps H, Basten O, et al. Chronic myeloproliferative diseases with concurrent BCR-ABL junction and JAK2V617F mutation. Leukemia. 2008;22:1059–1062. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RK, Lea NC, Heneghan MA, Westwood NB, Milojkovic D, Thanigaikumar M, et al. Prevalence of the activating JAK2 tyrosine kinase mutation V617F in the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2031–2038. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanne-Chantelot C, Jego P, Lionne-Huyghe P, Tulliez M, Najman A. The JAK2(V617F) mutation may be present several years before the occurrence of overt myeloproliferative disorders. Leukemia. 2008;22:450–451. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Sirhan S, Lasho TL, Schwager SM, Li CY, Dingli D, et al. Concomitant neutrophil JAK2 mutation screening and PRV-1 expression analysis in myeloproliferative disorders and secondary polycythaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzner I, Weniger MA, Menz CK, Moller P. Absence of the JAK2 V617F activating mutation in classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2006;20:157–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti F, Rumi E, Pietra D, Lazzarino M, Cazzola M. JAK2 (V617F) mutation in healthy individuals. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:678–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RL, Loriaux M, Huntly BJ, Loh ML, Beran M, Stoffregen E, et al. The JAK2V617F activating mutation occurs in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia, but not in acute lymphoblastic leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:3377–3379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpivaara O, Levine RL. JAK2 and MPL mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms: discovery and science. Leukemia. 2008;22:1813–1817. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Levine R, Tong W, Wernig G, Pikman Y, Zarnegar S, et al. Expression of a homodimeric type I cytokine receptor is required for JAK2V617F-mediated transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18962–18967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509714102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi-Tago M, Tago K, Abe M, Sonoda Y, Kasahara T. STAT5 activation is critical for the transformation mediated by myeloproliferative disorder-associated JAK2 V617F mutant. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5296–5307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson MA, Bannister AJ, Gottgens B, Foster SD, Bartke T, Green AR, et al. JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3Y41 and excludes HP1alpha from chromatin. Nature. 2009;461:819–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota J, Caceres N, Constantinescu SN. Aberrant signal transduction pathways in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2008;22:1828–1840. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WX. Canonical and non-canonical JAK-STAT signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleyrat C, Jelinek J, Girodon F, Boissinot M, Ponge T, Harousseau JL, et al. JAK2 mutation and disease phenotype: a double L611V/V617F in cis mutation of JAK2 is associated with isolated erythrocytosis and increased activation of AKT and ERK1/2 rather than STAT5 Leukemia 2010(e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Akada H, Yan D, Zou H, Fiering S, Hutchison RE, Mohi MG.Conditional expression of heterozygous or homozygous Jak2V617F from its endogenous promoter induces a polycythemia vera-like disease Blood 2010(e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang YL, Vandris K, Jones A, Cross NC, Christos P, Adriano F, et al. JAK2 mutations are present in all cases of polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2008;22:1289. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Finke C, Hanson CA, Tefferi A. Prevalence and clinicopathologic correlates of JAK2 exon 12 mutations in JAK2V617F-negative polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2007;21:1960–1963. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietra D, Li S, Brisci A, Passamonti F, Rumi E, Theocharides A, et al. Somatic mutations of JAK2 exon 12 in patients with JAK2 (V617F)-negative myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2008;111:1686–1689. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. The complete evaluation of erythrocytosis: congenital and acquired. Leukemia. 2009;23:834–844. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Reis Monte-Mor B, Plo I, da Cunha AF, Costa GG, de Albuquerque DM, Jedidi A, et al. Constitutive JunB expression, associated with the JAK2 V617F mutation, stimulates proliferation of the erythroid lineage. Leukemia. 2009;23:144–152. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plo I, Nakatake M, Malivert L, de Villartay JP, Giraudier S, Villeval JL, et al. JAK2 stimulates homologous recombination and genetic instability: potential implication in the heterogeneity of myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2008;112:1402–1412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedt R, Hao-Shen H, Sobas MA, Looser R, Dirnhofer S, Schwaller J, et al. Ratio of mutant JAK2-V617F to wild-type Jak2 determines the MPD phenotypes in transgenic mice. Blood. 2008;111:3931–3940. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shide K, Shimoda HK, Kumano T, Karube K, Kameda T, Takenaka K, et al. Development of ET, primary myelofibrosis and PV in mice expressing JAK2 V617F. Leukemia. 2008;22:87–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. Clinical correlates of JAK2V617F presence or allele burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms: a critical reappraisal. Leukemia. 2008;22:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theocharides A, Boissinot M, Girodon F, Garand R, Teo SS, Lippert E, et al. Leukemic blasts in transformed JAK2-V617F-positive myeloproliferative disorders are frequently negative for the JAK2-V617F mutation. Blood. 2007;110:375–379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal R, Belisle C, Lessard MC, Hebert J, Roy DC, Levine R, et al. Evidence suggesting the presence of a stem cell clone anteceding the acquisition of the JAK2-V617F mutation. Leukemia. 2008;22:1472–1474. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralovics R. Genetic complexity of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2008;22:1841–1848. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, Longo G, Pancrazzi A, Ponziani V, et al. Prospective identification of high-risk polycythemia vera patients based on JAK2(V617F) allele burden. Leukemia. 2007;21:1952–1959. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barosi G, Bergamaschi G, Marchetti M, Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P, Antonioli E, et al. JAK2 V617F mutational status predicts progression to large splenomegaly and leukemic transformation in primary myelofibrosis. Blood. 2007;110:4030–4036. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Schwager SM, Steensma DP, Mesa RA, Li CY, et al. The JAK2 tyrosine kinase mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia: lineage specificity and clinical correlates. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:320–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Strand JJ, Lasho TL, Knudson RA, Finke CM, Gangat N, et al. Bone marrow JAK2V617F allele burden and clinical correlates in polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2007;21:2074–2075. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittur J, Knudson RA, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Gangat N, Wolanskyj AP, et al. Clinical correlates of JAK2V617F allele burden in essential thrombocythemia. Cancer. 2007;109:2279–2284. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PJ, Griesshammer M, Dohner K, Dohner H, Kusec R, Hasselbalch HC, et al. V617F mutation in JAK2 is associated with poorer survival in idiopathic myelofibrosis. Blood. 2006;107:2098–2100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PJ, Scott LM, Buck G, Wheatley K, East CL, Marsden JT, et al. Definition of subtypes of essential thrombocythaemia and relation to polycythaemia vera based on JAK2 V617F mutation status: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;366:1945–1953. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67785-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palandri F, Ottaviani E, Salmi F, Catani L, Polverelli N, Fiacchini M, et al. JAK2 V617F mutation in essential thrombocythemia: correlation with clinical characteristics, response to therapy and long-term outcome in a cohort of 275 patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:247–253. doi: 10.1080/10428190802688152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes F, Dupriez B, Pereira A, Passamonti F, Reilly JT, Morra E, et al. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Blood. 2009;113:2895–2901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmelli P, Barosi G, Specchia G, Rambaldi A, Lo Coco F, Antonioli E, et al. Identification of patients with poorer survival in primary myelofibrosis based on the burden of JAK2V617F mutated allele. Blood. 2009;114:1477–1483. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Huang J, Finke C, Mesa RA, Li CY, et al. Low JAK2V617F allele burden in primary myelofibrosis, compared to either a higher allele burden or unmutated status, is associated with inferior overall and leukemia-free survival. Leukemia. 2008;22:756–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti F, Rumi E, Pietra D, Elena C, Boveri E, Arcaini L, et al. Relationship between granulocyte JAK2 (V617F) mutant allele burden and risk of progression to myelofibrosis in polycythemia vera: a prospective study of 338 patients. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2009;114:751. [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Gilliland G.JAK2 mutations in myeloproliferative disorders N Engl J Med 20053531416–1417.author reply 1416–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Schwager SM, Strand JS, Elliott M, Mesa R, et al. The clinical phenotype of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous JAK2V617F in polycythemia vera. Cancer. 2006;106:631–635. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, Rambaldi A, Barosi G, Marchioli R, et al. Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V>F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110:840–846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbui T, Carobbio A, Cervantes F, Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P, Antonioli E, et al. Thrombosis in primary myelofibrosis: incidence and risk factors Blood 2010115778–782.blood-2009-2008-238956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politou M, Zoi C, Dahabreh IJ, Rallidis L, Gialeraki A, Loukopoulos D, et al. No evidence of frequent association of the JAK2 V617F mutation with acute myocardial infarction in young patients. Leukemia. 2009;23:1008–1009. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher CM, Hahn U, To LB, Gecz J, Wilkins EJ, Scott HS, et al. Two novel JAK2 exon 12 mutations in JAK2V617F-negative polycythaemia vera patients. Leukemia. 2008;22:870–873. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Thiele J, Orazi A, Kvasnicka HM, Barbui T, Hanson CA, et al. Proposals and rationale for revision of the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis: recommendations from an ad hoc international expert panel. Blood. 2007;110:1092–1097. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti F, Schnittger S, Girodon F, Kiladjian J-J, McMullin MF, Ruggeri M, et al. Molecular and clinical features of the myeloproliferative neoplasm associated with JAK2 exon 12 mutations: a European Multicenter Study. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2009;114:3904. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Aviles L, Besses C, Alvarez-Larran A, Cervantes F, Hernandez-Boluda JC, Bellosillo B. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera or idiopathic erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2007;92:1717–1718. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teofili L, Giona F, Torti L, Cenci T, Ricerca BM, Rumi C, et al. Hereditary thrombocytosis caused by MPLSer505Asn is associated with a high thrombotic risk, splenomegaly and progression to bone marrow fibrosis. Haematologica. 2010;95:65–70. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.007542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moliterno AR, Williams DM, Gutierrez-Alamillo LI, Salvatori R, Ingersoll RG, Spivak JL. Mpl Baltimore: a thrombopoietin receptor polymorphism associated with thrombocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11444–11447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404241101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein K, Bock O, Theophile K, Schulz-Bischof K, Porwit A, Schlue J, et al. MPLW515L mutation in acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:852–855. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Haferlach C, Beelen DW, Bojko P, Dengler R, Diestelrath A, et al. Detection of three different MPLW515 mutations in 10.1% of all JAK2 V617 unmutated ET and 9.3% of all JAK2 V617F unmutated OMF: a study of 387 patients. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2007;110:2546. [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Pancrazzi A, Guglielmelli P, Di Lollo S, Alterini R, et al. The clinical phenotype of patients with essential thrombocythemia harboring MPL 515W>L/K mutation. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2007;110:678. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmelli P, Pancrazzi A, Bergamaschi G, Rosti V, Villani L, Antonioli E, et al. Anaemia characterises patients with myelofibrosis harbouring Mpl mutation. Br J Haematol. 2007;137:244–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer PA, Campbell PJ, Scott LM, Bench AJ, Erber WN, Bareford D, et al. MPL mutations in myeloproliferative disorders: analysis of the PT-1 cohort. Blood. 2008;112:141–149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-131664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaligne R, James C, Tonetti C, Besancenot R, Le Couedic JP, Fava F, et al. Evidence for MPL W515L/K mutations in hematopoietic stem cells in primitive myelofibrosis. Blood. 2007;110:3735–3743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaligne R, Tonetti C, Besancenot R, Roy L, Marty C, Mossuz P, et al. New mutations of MPL in primitive myelofibrosis: only the MPL W515 mutations promote a G1/S-phase transition. Leukemia. 2008;22:1557–1566. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecquet C, Staerk J, Chaligne R, Goss V, Lee KA, Zhang X, et al. Induction of myeloproliferative disorder and myelofibrosis by thrombopoietin receptor W515 mutants is mediated by cytosolic tyrosine 112 of the receptor. Blood. 2010;115:1037–1048. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasho TL, Pardanani A, McClure RF, Mesa RA, Levine RL, Gary Gilliland D, et al. Concurrent MPL515 and JAK2V617F mutations in myelofibrosis: chronology of clonal emergence and changes in mutant allele burden over time. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:683–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpurka H, Gondek LP, Mohan SR, Hsi ED, Theil KS, Maciejewski JP. UPD1p indicates the presence of MPL W515L mutation in RARS-T, a mechanism analogous to UPD9p and JAK2 V617F mutation. Leukemia. 2009;23:610–614. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, Pancrazzi A, Guerini V, Barosi G, et al. Characteristics and clinical correlates of MPL 515W>L/K mutation in essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2008;112:844–847. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorsbach RB, Moore J, Mathew S, Raimondi SC, Mukatira ST, Downing JR. TET1, a member of a novel protein family, is fused to MLL in acute myeloid leukemia containing the t(10;11)(q22;q23) Leukemia. 2003;17:637–641. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viguie F, Aboura A, Bouscary D, Ramond S, Delmer A, Tachdjian G, et al. Common 4q24 deletion in four cases of hematopoietic malignancy: early stem cell involvement. Leukemia. 2005;19:1411–1415. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Pardanani A, Lim KH, Abdel-Wahab O, Lasho TL, Patel J, et al. TET2 mutations and their clinical correlates in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2009;23:905–911. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Levine RL, Lim KH, Abdel-Wahab O, Lasho TL, Patel J, et al. Frequent TET2 mutations in systemic mastocytosis: clinical, KITD816V and FIP1L1-PDGFRA correlates. Leukemia. 2009;23:900–904. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Lim KH, Abdel-Wahab O, Lasho TL, Patel J, Patnaik MM, et al. Detection of mutant TET2 in myeloid malignancies other than myeloproliferative neoplasms: CMML, MDS, MDS/MPN and AML. Leukemia. 2009;23:1343–1345. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langemeijer SM, Kuiper RP, Berends M, Knops R, Aslanyan MG, Massop M, et al. Acquired mutations in TET2 are common in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2009;41:838–842. doi: 10.1038/ng.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Wahab O, Mullally A, Hedvat C, Garcia-Manero G, Patel J, Wadleigh M, et al. Genetic characterization of TET1, TET2, and TET3 alterations in myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009;114:144–147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Cheok M, Grabar S, Della-Valle V, Picard F, et al. TET2 mutation is an independent favorable prognostic factor in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) Blood. 2009;114:3285–3291. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamedali AM, Smith AE, Gaken J, Lea NC, Mian SA, Westwood NB, et al. Novel TET2 mutations associated with UPD4q24 in myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4002–4006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska AM, Szpurka H, Tiu RV, Makishima H, Afable M, Huh J, et al. Loss of heterozygosity 4q24 and TET2 mutations associated with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2009;113:6403–6410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsson K, Haferlach C, Fonatsch C, Hagemeijer A, Andersen MK, Slovak ML, et al. The idic(X)(q13) in myeloid malignancies: breakpoint clustering in segmental duplications and association with TET2 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1507–1514. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein K, Van Dyke DL, Tefferi A. Conventional cytogenetics in myelofibrosis: literature review and discussion. Eur J Haematol. 2009;82:329–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Lim KH, Levine R.Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers N Engl J Med 20093611117author reply 1117–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein K, Abdel-Wahab O, Lasho TL, Van Dyke DL, Levine RL, Hanson CA, et al. Cytogenetic correlates of TET2 mutations in 199 patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:81–83. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Ciudad M, Racoeur C, Jooste V, Vey N, et al. TET2 gene mutation is a frequent and adverse event in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2009;94:1676–1681. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couronne L, Lippert E, Andrieux J, Kosmider O, Radford-Weiss I, Penther D, et al. Analyses of TET2 mutations in post-myeloproliferative neoplasm acute myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 2010;24:201–203. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SW, Cho YS, Na JM, Park UH, Kang M, Kim EJ, et al. ASXL1 represses retinoic acid receptor-mediated transcription through associating with HP1 and LSD1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Fisher CL, Pineault N, Brookes C, Helgason CD, Ohta H, Bodner C, et al. Loss-of-function additional sex combs-like1 mutations disrupt hematopoiesis but do not cause severe myelodysplasia or leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:38–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Q, Wright SL, Konn ZJ, Matheson E, Minto L, Moorman AV, et al. Variable breakpoints target PAX5 in patients with dicentric chromosomes: a model for the basis of unbalanced translocations in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17050–17054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803494105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adelaide J, Bonansea J, Cervera N, Carbuccia N, et al. Mutations of polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:788–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbuccia N, Trouplin V, Gelsi-Boyer V, Murati A, Rocquain J, Adelaide J, et al. Mutual exclusion of ASXL1 and NPM1 mutations in a series of acute myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 2010;24:469–473. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan G, Tsygankov AY. The Cbl family proteins: ring leaders in regulation of cell signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:21–43. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saur SJ, Sangkhae V, Geddis AE, Kaushansky K, Hitchcock IS. Ubiquitination and degradation of the thrombopoietin receptor c-Mpl. Blood. 2010;115:1254–1263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi SR, Brandts C, Rensinghoff M, Grundler R, Tickenbrock L, Kohler G, et al. E3 ligase-defective Cbl mutants lead to a generalized mastocytosis and myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2009;114:4197–4208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-190934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargin B, Choudhary C, Crosetto N, Schmidt MH, Grundler R, Rensinghoff M, et al. Flt3-dependent transformation by inactivating c-Cbl mutations in AML. Blood. 2007;110:1004–1012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanada M, Suzuki T, Shih LY, Otsu M, Kato M, Yamazaki S, et al. Gain-of-function of mutated C-CBL tumour suppressor in myeloid neoplasms. Nature. 2009;460:904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature08240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JF, Hsu JJ, Tang TC, Shih LY. Identification of CBL, a proto-oncogene at 11q23.3, as a novel MLL fusion partner in a patient with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;37:214–219. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh ML, Sakai DS, Flotho C, Kang M, Fliegauf M, Archambeault S, et al. Mutations in CBL occur frequently in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:1859–1863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makishima H, Cazzolli H, Szpurka H, Dunbar A, Tiu R, Huh J, et al. Mutations of e3 ubiquitin ligase cbl family members constitute a novel common pathogenic lesion in myeloid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6109–6116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Makishima H, Jankowska AM, Cazzolli H, O'Keefe C, Yoshida N, et al. Mutations of E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl family members but not TET2 mutations are pathogenic in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:1969–1975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-226340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1872–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flach J, Dicker F, Schnittger S, Kohlmann A, Haferlach T, Haferlach C. Mutations of JAK2 and TET2, but not CBL are detectable in a high portion of patients with refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis (RARS-T) Haematologica. 2010;95:518–519. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.013631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas S, Rotmans G, Lowenberg B, Valk PJ. Exon 8 splice site mutations in the gene encoding the E3-ligase CBL are associated with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemias. Haematologica. 2008;93:1595–1597. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reindl C, Quentmeier H, Petropoulos K, Greif PA, Benthaus T, Argiropoulos B, et al. CBL exon 8/9 mutants activate the FLT3 pathway and cluster in core binding factor/11q deletion acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2238–2247. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Chen K, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PS, Patel J, Wise DR, Abdel-Wahab O, Bennett BD, Coller HA, et al. The common feature of leukemia-associated idh1 and idh2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S, Cairns RA, Minden MD, Driggers EM, Bittinger MA, Jang HG, et al. Cancer-associated metabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate accumulates in acute myelogenous leukemia with isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations. J Exp Med. 2010;207:339–344. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaal J, Burnichon N, Korpershoek E, Roncelin I, Bertherat J, Plouin PF, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations are rare in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1274–1278. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SW, Chung NG, Han JY, Eom HS, Lee JY, Yoo NJ, et al. Absence of IDH2 codon 172 mutation in common human cancers. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2485–2486. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MR, Kim MS, Oh JE, Kim YR, Song SY, Seo SI, et al. Mutational analysis of IDH1 codon 132 in glioblastomas and other common cancers. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:353–355. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeker FE, Lamba S, Leenstra S, Troost D, Hulsebos T, Vandertop WP, et al. IDH1 mutations at residue p.R132 (IDH1(R132)) occur frequently in high-grade gliomas but not in other solid tumors. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:7–11. doi: 10.1002/humu.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Lin Y, Xu W, Jiang W, Zha Z, Wang P, et al. Glioma-derived mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and induce HIF-1alpha. Science. 2009;324:261–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1170944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balss J, Meyer J, Mueller W, Korshunov A, Hartmann C, von Deimling A. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:597–602. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobusawa S, Watanabe T, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations as molecular signature and predictive factor of secondary glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6002–6007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C, Meyer J, Balss J, Capper D, Mueller W, Christians A, et al. Type and frequency of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are related to astrocytic and oligodendroglial differentiation and age: a study of 1,010 diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:469–474. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravendeel LA, Kloosterhof NK, Bralten LB, van Marion R, Dubbink HJ, Dinjens W, et al. Segregation of non-p.R132H mutations in IDH1 in distinct molecular subtypes of glioma. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:E1186–E1199. doi: 10.1002/humu.21201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson M, Marie Y, Paris S, Idbaih A, Laffaire J, Ducray F, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 codon 132 mutation is an important prognostic biomarker in gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4150–4154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]