Abstract

Chiral α,β-dihydroxy carboxylic acids catalyze the enantioselective addition of alkenyl- and aryl boronates to chromene acetals. The optimal carboxylic acid is a tartaric acid amide, easily synthesized via a 3-step procedure. The reaction is enhanced by the addition of Lanthanide triflate salts such as cerium(IV)-and ytterbium(III) triflate. The chiral Brønsted acid and metal Lewis acid may be used in as low as 5 mol % relative to acetal substrate. Optimization of the reaction conditions can lead to yields >70% and enantiomeric ratios as high as 99:1. Spectroscopic and kinetic mechanistic studies demonstrate an exchange process leading to a reactive dioxoborolane intermediate leading to enantioselective addition to the pyrylium generated from the chromene acetal.

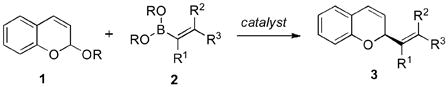

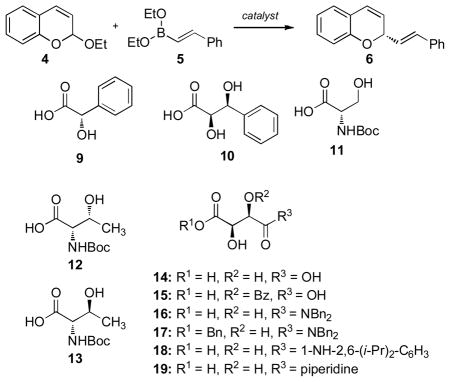

Boronates exhibit wide-ranging utility in synthesis.[1] As carbon donors in cross coupling reactions[2] and metal-based nucleophiles in π addition reactions,[3] their utility is characterized by their ease of preparation, stability towards isolation and storage, and predictable reactivity patterns to afford valuable products.[4] In a seminal discovery Petasis demonstrated how boronates could be activated towards addition to iminiums.[5] However, an elusive area of reactivity is the addition of vinyl and aryl boronates to carbonyls and oxoniums.[6] While less reactive than imines and iminiums, carbonyl-based electrophiles would significantly expand the utility of boronates in synthesis. Coincident with our interest in new reaction methodology[7] we sought to expand the repertoire of nucleophilic boronate reactions to enantioselective addition to acetals.[8] We identified 2-alkoxy-2H-chromenes as our first substrate class for investigation [Eq. (1)].[9]

|

(1) |

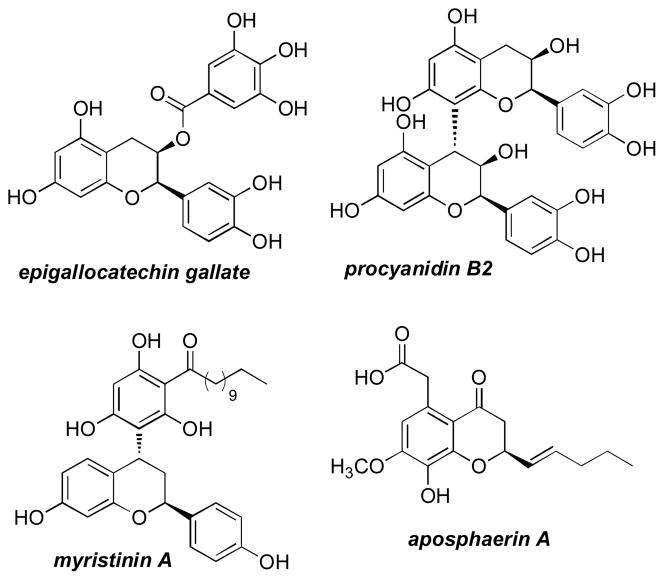

The addition of vinyl and aryl based nucleophiles to this class of electrophiles give rise to chiral chromene products[10] that could readily be utilized in the synthesis of benzopyran containing natural products (Figure 1) such as epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a nutraceutical with potent antioxidant properties,[11] procyanidin B2, a proapoptotic polyphenol,[12] myristinin A, an inhibitor of DNA polymerase B,[13] and the antibacterial fungal metabolite aposphaerin A.[14] A general synthetic method to access this structural class in enantioenriched form would be attractive.[15] Herein, we describe the development of an enantioselective boronate addition to chromene acetals catalyzed by a chiral Brønsted acid – metal salt Lewis acid system.

Figure 1.

Natural product benzopyrans

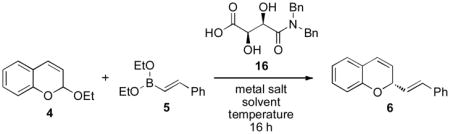

We initiated our study by investigating the addition of boronate 5 to 2-ethoxy-2H-chromene 4 (Table 1). A brief survey of Lewis acids failed, providing none of the desired addition product when used in catalytic amount and led to substantial decomposition of the chromene 4. We postulated that organic acids would serve as mild catalysts for the formation of the pyrylium, thereby promoting the reaction. Indeed, the use of acetic acid and trifluoroacetic acid provided the desired addition product 6 in modest yields (Table 1, entries 1 & 2).

Table 1.

Acid catalyzed addition of boronate 5 to 2-ethoxy-2H-chromene 4.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Yield[b] | e.r.[c] |

| 1 | 7: AcOH | 33 | -- |

| 2 | 8: TFA | 43 | -- |

| 3 | 9 | 50 | 59:41 |

| 4 | 10 | 26 | 50:50 |

| 5 | 11 | 55 | 63:37 |

| 6 | 12 | 38 | 54:46 |

| 7 | 13 | 46 | 66:34 |

| 8 | 14 | 81 | 63:37 |

| 9 | 15 | 59 | 55:45 |

| 10 | 16 | 44 | 83:17 |

| 11 | 17 | 0 | -- |

| 12 | 18 | 54 | 82:18 |

| 13 | 19 | 40 | 81:19 |

Reactions were run with 0.50 mmol chromene 4, 0.75 mmol boronate 5, 16 and metal salt in EtOAc (1 mL) for 16 h at rt under Ar, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

Enantiomeric ratios determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Encouraged by these preliminary results, we explored the use of available chiral acids. (+)-Mandelic acid 9 and dihydroxy acid 10 were nominally successful at promoting the enantioselective addition reaction (entries 3 & 4). However, the use of catalytic N-Boc amino acids derived from L-serine and L-threonine resulted in a more selective reaction. Notably, L-threonine 12 afforded the product in lower selectivity than L-serine 11 (entries 5 & 6); enantioselectivity that returned upon use of the epimeric allo-L-threonine (entry 7). Theses results led us to consider chiral acids that possess hydroxyl groups at the β-position of the carboxylic acid; namely tartaric acid and derivatives. (+)-Tartaric acid provided similar levels of enantioselectivity to serine derived catalyst 11 (entry 8); however, conversion of one of the hydroxyl groups to an ester ablated selectivity (entry 9). Alternatively, amides of tartaric acid provided the highest enantioselectivities in the reaction (entries 10 – 13) and were thusly selected as the catalyst design for further investigation.

The initial results were promising but far from ideal. Tartaric acid derived amides[16] were an excellent staring point as asymmetric catalysts but despite relatively high catalyst concentrations, the enantioselectivities were moderate and catalytic efficiency low. Solvent selection could provide some increase in catalysis but failed to give rise to correspondingly higher levels of enantioselectivity (Table 2, entries 1 – 4). We postulated that the addition of a metal-derived Lewis acid would increase the catalytic efficiency of the Brønsted acid catalyst. A concept pioneered by Prof Hisashi Yamamoto, Lewis acid-assisted Brønsted acids[17] were originally developed for enantioselective protonation reactions.[18] Furthermore, Lewis acids are capable of facilitating allylboration reactions; observations made by Hall,[19] Ishiyama and Miyaura.[20] The addition of Zn(OTf)2 to the reaction of 4 and 5 in the presence of acid 16 resulted in a slight increase in selectivity but almost no change in the isolated yield (entry 5, Table 2). A noticeable change to the reaction was significant levels of decomposition; the additional Lewis acid either degraded the starting material or product. Reducing the amount of the Brønsted acid-Lewis acid combination resulted in a substantial increase in the enantioselectivity of the reaction and a slight increase in yield, again due to decomposition (entry 6). The triflate counterion appeared to be the best and Zn(OTf)2 was substantially better than the more commonly employed triflate salt, Sc(OTf)3 (entry 9). However, the use of Ce(OTf)4[21] resulted in a substantially improved reaction obtaining good yields and the highest enatioselectivities (39:1 e.r., entry 10).

Table 2.

Use of Lewis acids in the addition of boronates to 2-ethoxy-2H-chromene 4.[a]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | mol% 16 | Metal salt | mol% | Solvent | T (°C) | Yield[b] | e.r.[c] |

| 1 | 30 | – | – | EtOAc | 20 | 44% | 83:17 |

| 2 | 30 | – | – | PhCH3 | 20 | 72% | 80:20 |

| 3 | 30 | – | – | THF | 20 | <5% | ND |

| 4 | 30 | – | – | CH2Cl2 | 20 | 51% | 82:18 |

| 5 | 30 | Zn(OTf)2 | 30 | EtOAc | 20 | 45% | 84:16 |

| 6 | 5 | Zn(OTf)2 | 4.5 | EtOAc | 20 | 54% | 94:6 |

| 7 | 5 | Zn(OTs)2 | 4.5 | EtOAc | 20 | 18% | 84:16 |

| 8 | 5 | Zn(TFA)2 | 4.5 | EtOAc | 20 | 8% | 65:35 |

| 9 | 5 | Sc(OTf)3 | 4.5 | EtOAc | 20 | 18% | 66:34 |

| 10 | 5 | Ce(OTf)4 | 4.5 | EtOAc | 20 | 65% | 97.5:2.5 |

| 11 | - | Ce(OTf)4 | 4.5 | EtOAc | 20 | <2% | ND |

| 12 | 5 | Ce(OTf)4 | 4.5 | EtOAc | −20 | 75% | 97.5:2.5 |

| 13 | 5 | Ce(OTf)4 | 4.5 | EtOAc | −40 | 83% | 99:1 |

| 14 | 5 | Yb(OTf)3 | 4.5 | EtOAc | −40 | 87% | 98.5:1.5 |

| 15 | 5 | Ce(OTf)3 | 4.5 | EtOAc | −40 | 78% | 96:4 |

Reactions were run with 0.50 mmol chromene 4, 0.75 mmol boronate 5, 16 and metal salt in solvent (1 mL) for 16 h at the indicated temperature under Ar, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

Enantiomeric ratios determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

The omission of acid catalyst 16 resulted in almost no conversion indicating that the primary mode of enantioselective catalysis had not changed (entry 11). Lower temperatures improved the chemo- and enantioselectivity of the reaction (entries 12 – 13) while Ce(III), Ce(IV), and Yb(III) triflate salts all gave comparably high yields and enantioselectivities. At the conclusion of the initial optimization studies, we had identified a set of conditions that utilized a chiral Brønsted acid – metal triflate Lewis acid catalytic system to achieve a highly enantioselective reaction.

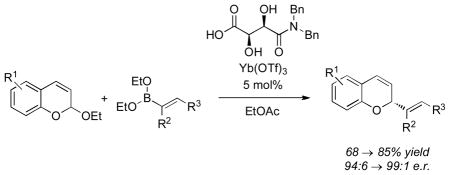

The Brønsted acid – Lewis acid catalytic reaction conditions proved general for a range of boronate additions to chromene acetals. However, optimal yields and selectivities required further experimentation and were found to be dependent on the electronic nature chromene acetal and boronate employed in the reaction. The parameters used to moderate the reaction were temperature, catalyst identity and concentration, and t-BuOH; an additive that decreases the rate of starting material decomposition, but unfortunately, also the rate of the addition reaction. For example, reactions using less reactive boronates could be executed at 4 °C whereas more reactive boronates required lower temperatures (−40 °C) and the addition of t-BuOH to attenuate the reactivity (entries 1 & 2, Table 3). Similar observations were made of electron deficient and electron rich chromene acetals (entries 5 – 8). However, good yields and high enantioselectivities were achieved with alkenyl boronate nucleophiles (entries 1 – 8). Aryl boronates proved to be less reactive and required activating groups on the aromatic ring such as methoxy substitution. Higher catalyst loadings were used to achieve the desired reaction rates, but increased catalyst concentrations also led to product decomposition. The addition of t-BuOH tempered the amount of decomposition observed (entries 9 – 14). Oxygenation of the chromene acetal led to low reaction yields and selectivities with the addition of aryl boronates. However, the donating capability of the oxygen substitution could be attenuated using a dimethyl carbamate rather than a methoxy group achieving good yields and high selectivities in the addition reaction (entries 13 & 14). While no single set of reaction conditions were applicable to all of the substrates evaluated, an optimal set could be identified for each substrate based on an understanding of the reactivity.

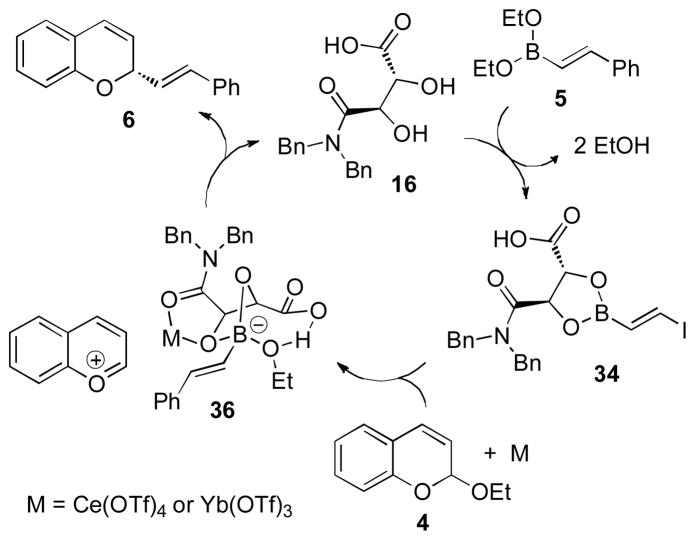

Studies were performed to ascertain the roles of the catalysts and the species formed during the course of the reaction. First, the addition of boronate 5 to diol 16 results in an exchange process to form the corresponding dioxaborolane 34 (Figure 3). 1H NMR analysis of the catalyst-boronate complex 34 illustrated the methine protons, doublets at 4.87 and 4.46 ppm, shifted downfield to 5.62 and 5.29 ppm within 2 min of boronate addition. Direct injection electron spray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis of the complex detected the sodium salt dioxaborolane 35 (calculate M-H+Na: 463.2, measured: 463.7). The spectroscopic and spectrometric evidence supported the formation of dioxoborolane 35; however, the role of the carboxylic acid and amide moieties was not clear. While the carboxylic acid is necessary for catalysis (entry 11, Table 1), a structural or catalytic role could not be discerned. Although there was evidence for dioxaborolane 34, the possibility remained that the dioxaborolane might be forming by exchange with one of the alcohols and the carboxylate.[22] The use of in situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was used to characterize the structure of the dioxaborolane. The catalyst was dissolved in EtOAc and the carbonyl of the carboxylic acid absorbance was assigned to 1757 cm−1 and the amide was assigned to 1653 cm−1(in situ FT-IR, Figure 2). Boronate 5 and carboxylic acid 16 were mixed and the carbonyl shifts monitored. The absorbances did not shift indicating the exchange occurred exclusively to form dioxoborolane 34. Next, the interaction of Ce(OTf)4 with 34 was investigated using ESI-MS and FT-IR. The addition of Ce(OTf)4 to 34 under the reaction conditions was then analyzed by ESI-MS. A 1:1 complex of 34 and Ce(OTf)4 was detected (34 + Ce(OTf)3 mass: 1027). However, the presence of the complex does not demonstrate how the Ce(OTf)4 interacts with the dioxaborolane. To ascertain the type of complexation, in situ FT-IR was used. To a solution of boronate 34 was added Ce(OTf)4. The carboxylic acid absorbance did not shift whereas the amide began to shift from 1653 to 1609 cm−1. Continued addition of Ce(OTf)4 (>1 molar equivalent) began to affect the carbonyl of the carboxylic acid. Complexation of the metal appears to be selective for the amide carbonyl under the reaction conditions, and in line with previous work involving boronates and Lewis acids, the Ce(OTf)4 is likely to bind with the oxygen of the boronate as well.[23] Detection of the oxocarbenium species was also performed. Benzopyrylium species exhibit UV-visible absorbances at 400–600 nm.[24] The spectroscopic analysis showed a distinct peak at 449 nm over the course of time indicating the formation of a pyrylium intermediate. Kinetic evaluation of the reaction demonstrated a first-order dependence of tartaramide acid catalyst 16 and Ce(OTf)4, consistent with the spectroscopic data. Finally, the addition of chiral dioxoborolane 34 to chromene acetal 4 promoted by Ce(OTf)4 afforded the addition product 6 in 85% isolated yield and 98:2 e.r. (Eq. 2), supporting the intermediacy of 34 in the catalytic process.

Figure 3.

Proposed catalytic cycle.

|

(2) |

Our preliminary studies indicate a possible catalytic cycle (Figure 3). The catalytic cycle begins with the formation of dioxaborolane 34 from the boronate and tartaramide acid 16. The addition of Lewis acid to complex 34 enhances the acidity of the boronate. Thusly with the addition of chromene acetal, the boronate serves to facilitate pyrylium formation concomitant with generation of boronate 36. Activation via formation of the “ate” complex 36 leads to the nucleophilic addition of the styryl group to the electrophile. Nucleophilic delivery serves to provide the necessary reservoir of tartaramide acid 16 for re-entry into the catalytic cycle. The proposed activation of the boronate accounts for the enhancing role of the Lewis acid, although not crucial for reactivity and is consistent with the spectroscopic, spectrometric, and kinetic studies. Continued investigations focus on the physical characteristics of boronate 34, the mode of enantioselectivity, and the catalytic turnover processes.

In summary, we have developed a dual catalyst system for the enantioselective addition of boronates to oxoniums. The catalyst system is a tarataric acid-derived Brønsted acid used in conjunction with a Lanthanide triflate Lewis acid used in catalytic amounts to promote the enantioselective addition of alkenyl and aryl boronates to chromene acetals. The reaction was optimized for a range of chromene acetals possessing both electron deficient and electron rich substitution patterns. Mechanistic studies demonstrate an exchange process leading to a reactive dioxoborolane intermediate. Ongoing studies include further mechanistic investigations, expansion of the scope and utility for the synthesis of natural products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH (R01 GM078240) and Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd. TK gratefully acknowledges support as a visiting scientist from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.Hall DG. Boronic Acids—Preparations and applications in organic synthesis and medicine. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457–2483. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ley SV, Thomas AW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:5400–5449. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Chemler SR, Roush WR. In: Modern Carbonyl Chemistry. Otera J, editor. Chapter 11. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. p. 403. [Google Scholar]; (b) Denmark SE, Almstead NG. In: Modern Carbonyl Chemistry. Otera J, editor. Chapter 10. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown HC. Organic synthesis via boranes. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 1975. [Google Scholar]; (b) Matteson DS. Stereodirected synthesis with organoboranes. Springer; 1995. [Google Scholar]; (c) Roy CD, Brown HC. Monatsh Chem. 2007;138:879–887. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Petasis NA, Akritopoulou I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:583–586. [Google Scholar]; (b) Petasis NA. Aust J Chem. 2007;60:795–798. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Wu RT, Chong JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4908–4909. doi: 10.1021/ja0713734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mitchell TA, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18057–18058. doi: 10.1021/ja906514s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lou S, Moquist PN, Schaus SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12660–12661. doi: 10.1021/ja0651308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bishop JA, Lou S, Schaus SE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4337–4340. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Oguri H, Tanaka S, Oishi T, Hirama M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:975–978. [Google Scholar]; (b) Reisman SE, Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7198–7199. doi: 10.1021/ja801514m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schneider U, Dao HT, Kobayashi S. Org Lett. doi: 10.1021/ol100450s. ASAP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doodeman R, Rutjes FPJT, Hiemstra H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:5979–5983. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Harrity JPA, La DS, Cefalo DR, Visser MS, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:2343–2351. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wipf P, Weiner WS. J Org Chem. 1999;64:5321–5324. doi: 10.1021/jo990352s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Jankun J, Selman SH, Swiercz R, Skrzypczak-Jankun E. Nature. 1997;387:561. doi: 10.1038/42381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stoner GD, Mukhtar H. J Cell Biochem. 1995;59:169–180. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Foo LY, Porter LJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1983;1:1535–1543. [Google Scholar]; (b) Williamson G, Manach C. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:243S–255S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.243S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Sawadjoon S, Kittakoop P, Kirtikara K, Vichai V, Tanticharoen M, Thebtaranonth Y. J Org Chem. 2002;67:5470–5475. doi: 10.1021/jo020045d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Deng JZ, Starck SR, Li S, Hecht SM. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1625–1628. doi: 10.1021/np058064g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albrecht U, Lalk M, Langer P. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:1531–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Trost BM, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9074–9075. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hodgetts KJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:8655–8659. [Google Scholar]; (c) Biddle MM, Lin M, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3830–3831. doi: 10.1021/ja070394v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobashi Y, Hara S. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2490–2496. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto H, Futatsugi K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:1924–1942. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishihara K, Kaneeda M, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:11179–11180. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy JWJ, Hall DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11586–11587. doi: 10.1021/ja027453j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishiyama T, Ahiko T, Miyaura N. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12414–12415. doi: 10.1021/ja0210345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans DA, Song HJ, Fandrick KR. Org Lett. 2006;8:3351–3354. doi: 10.1021/ol061223i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houston TA, Levonis SM, Kiefel MJ. Aust J Chem. 2007;60:811–815. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Rauniyar V, Hall DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4518–4519. doi: 10.1021/ja049446w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sakata K, Fujimoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12519–12526. doi: 10.1021/ja804168z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katritzky AR, Czerney P, Levell JR, Du W. Eur J Org Chem. 1998:2623–2629. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.