Abstract

Recovery is commonly used as an outcome measure in low back pain (LBP) research. There is, however, no accepted definition of what recovery involves or guidance as to how it should be measured. The objective of the study was designed to appraise the LBP literature from the last 10 years to review the methods used to measure recovery. The research design includes electronic searches of Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane database of clinical trials and PEDro from the beginning of 1999 to December 2008. All prospective studies of subjects with non-specific LBP that measured recovery as an outcome were included. The way in which recovery was measured was extracted and categorised according to the domain used to assess recovery. Eighty-two included studies used 66 different measures of recovery. Fifty-nine of the measures did not appear in more than one study. Seventeen measures used pain as a proxy for recovery, seven used disability or function and seventeen were based on a combination of two or more constructs. There were nine single-item recovery rating scales. Eleven studies used a global change scale that included an anchor of ‘completely recovered’. Three measures used return to work as the recovery criterion, two used time to insurance claim closure and six used physical performance. In conclusion, almost every study that measured recovery from LBP in the last 10 years did so differently. This lack of consistency makes interpretation and comparison of the LBP literature problematic. It is likely that the failure to use a standardised measure of recovery is due to the absence of an established definition, and highlights the need for such a definition in back pain research.

Keywords: Recovery, Low back pain, Outcome measurement, Systematic review

Introduction

The concept of ‘recovery’ from a disease or health condition is central to health care [80]. Within the low back pain (LBP) discipline, the concept of recovery is used in studies examining diagnosis [45], charting prognosis [44] and determining the effect of treatments [39]. Although the term ‘recovery’ is used commonly, there is no accepted definition of what recovery from LBP means or agreement on how it should be measured.

Despite the apparent simplicity of the idea, forming a coherent and appropriate definition of recovery from LBP is not a straightforward task. For example in some studies the term is used synonymously with global improvement [92], in others with improvement on various indicators such as disability [16] and return to work [69]. There is also a fundamental consideration regarding the meaning of recovery; that being whether recovery requires return to a prior health state or whether attainment of a fulfilling and satisfying life within the limitations of the condition is enough [21, 80]. The fact that LBP commonly follows an episodic or recurrent pattern [90] adds complexity to how recovery is conceptualised and measured.

It is worthwhile at this to point out the distinction between the definition of recovery and its measurement. While the problems with measurement of a concept in the absence of a standardised definition are self-evident, LBP researchers frequently measure recovery without an explicit statement of their definition of recovery [2]. This omission makes the process of reviewing definitions of recovery used by researchers problematic. Nevertheless, we can make inferences about definitions from the way in which recovery is currently measured; this information then can be used as a first step in formulating an acceptable definition. The aim of this study was to systematically review the LBP literature from the last ten years for measures used to assess recovery from LBP.

Methods

Search strategy

Studies were identified for inclusion in the review via sensitive searches of electronic databases. Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane database of clinical trials and PEDro were searched from the beginning of 1999 to December 2008. Keywords describing LBP (LBP OR back pain OR backache OR low back injury OR sciatica OR lumbago) AND recovery (recover$) OR resolution (resol$) were used to identify papers that measured recovery from LBP as an outcome.

Inclusion criteria

To be included studies needed to meet all of the following criteria.

A prospective, longitudinal study, including randomised controlled trials.

- Study population comprised patients with non-specific LBP.

- Non-specific LBP was defined as pain or discomfort, localised below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain.

The study reports ‘recovery’ or ‘resolution’ as an outcome measure in the “Abstract”, “Methods” or “Results”.

Exclusion criteria

Papers addressing surgical management of LBP.

Studies published prior to 1999.

Papers written in non-English languages where a translation could not be arranged.

Article inclusion

Two authors reviewed the database searches and excluded clearly ineligible studies based on titles and abstracts. Full reports of the remaining records were obtained and assessed for eligibility according to the inclusion criteria by the same two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved via consensus and consultation with a third author.

Data extraction

Measures of recovery were extracted from each of the included studies. Where sufficient information was reported, the domain and measurement tool used to measure recovery were also recorded. Where several measures were used, all were extracted and classified according to domain.

Results

Search

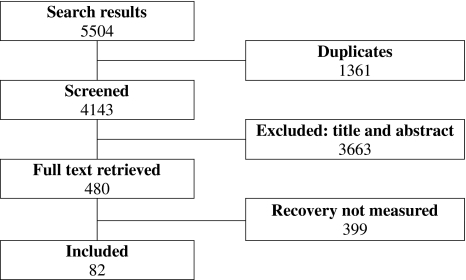

Figure 1 presents the numbers of papers screened and included in the review. From the electronic database search, a total of 5,504 papers were identified of which 82 [2–4, 6–15, 17–20, 23, 24, 26–40, 42–44, 46–49, 52–56, 59–64, 66–68, 70, 71, 73, 74, 76–79, 81–87, 91, 93, 95–102, 104, 105] papers met the inclusion criteria. In some instances, several papers reported on the same dataset, for the purposes of this study such papers were treated as a single study.

Fig. 1.

Search results

Measures of recovery

The 82 included studies reported 76 measures of recovery, among these were 66 different measures. One of the measures was used in five different studies [9, 42, 48, 52, 62, 63] and six other measures were used in two studies. However, the remaining 59 measures of recovery were not used in more than one study. The majority of studies used one measure of recovery, however six studies measured recovery in two ways [8, 13, 20, 34, 35, 60, 83], one study used three measures [19, 68] and one study had four different measures of recovery [44].

Of the 66 different measures reported, recovery was determined by a defined cut-off value on an established measurement instrument on 36 occasions. Five recovery measures were based on the answer to a direct question [8, 61, 68, 79, 101] (e.g. ‘have you had back pain in the previous week?”[79]), administrative data (e.g. time until insurance claim closure [14]) were used to measure recovery on three occasions [14, 34, 35, 91] and three studies described and quantified a physical performance test [4, 29, 47] (e.g. isokinetic muscle test [4]). Nineteen measures were described in a vague or uninformative manner that would preclude replication [6, 11, 26, 31, 33, 43, 49, 59, 70, 74, 81, 87, 93, 95, 100].

Seventeen studies used a minimum level of pain or ‘symptoms’ as a proxy for recovery; however, no two studies did so in exactly the same way (Table 1). Three recovery measures required the complete absence of pain, whereas three others fixed a cut-off score on the instrument [39, 40, 60, 66] that categorised subjects with minimal pain levels as recovered. The remaining studies gave a description of the symptomatic state necessary to indicate recovery. Seven studies determined recovery based on low or zero scores on disability questionnaires or required a return to previous levels of self-rated function (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pain and disability/function measures

| Study | Domain | Measure | Quantification | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGuirk [66] | Pain | VAS | <10/100 mm | – |

| Hancock [39, 40]a | Pain | NRS | ≤1/10 | 1 week |

| Collins [17] | Pain | NRS | 0/10 | – |

| Henschke [44] | Pain | SF-36: Item 7 | 0/6 (no LBP) | 1 month |

| Gheldof [32] | Pain | Nordic LBP Questionnaire | 0 days of pain in 12 months (acute) or ≤30 days of pain in 12 months (chronic) | 12 months |

| Linton [60] | Pain | Orebro: Item 10 × 11 | ≤16/100 | 3 months |

| Waxman [101] | Pain | Question | No to: “Have you had back pain in the past 12 months?” | 12 months |

| Long [61] | Pain | Question | Yes to: “My back pain has resolved” | |

| Reigo [79] | Pain | Question | No to: “Have you had back pain in the previous week?” | 1 week |

| Schattenkirchner [81] | Pain | Describedb | Early cure | – |

| Giles [33] | Pain | Describedb | Symptoms no longer present | – |

| Smith [87] | Pain | Describedb | Absence of continuous or I/T pain or discomfort | 3 months |

| Elders [26] | Pain | Describedb | Absence of LBP complaints | 1 year |

| Lake [59] | Pain | Describedb | No backache | 10 years |

| Naguszewski [70] | Pain | Describedb | Complete resolution of low back and leg pain | – |

| Finneran [31] | Pain | Describedb | Full subjective recovery from pain | – |

| Tubach [93] | Pain | Describedb | No LBP nor sciatica | – |

| Grotle [36, 37]a | Disability | RMDQ | ≤4/24 | – |

| Burton [12] | Disability | RMDQ | ≤2/24 | – |

| Henschke [44] | Disability | SF-36: Item 8 | 0/6 (no interference of LBP to normal work) | 1 month |

| Linton [60] | Disability | Orebro: sum items 21–25 | ≥45/50 | 3 months |

| Schiotz-Christensen [82] | Disability | Describedb | Able to manage ordinary daily activities | – |

| Carey [13]a, Curtis [20]a | Disability | Describedb | Able to perform daily activities as well as before this episode | – |

| Mielenz [68] | Disability | Describedb | Able to perform daily activities as well as before this episode | – |

VAS Visual analogue scale, NRS numerical rating scale, SF-36 Short Form 36 Quality of Life Questionnaire, RMDQ Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire

aTwo studies published from the same cohort

bRecovery measure was not described in sufficient detail to enable replication

Seventeen studies determined recovery based on a combination of two or more domains, most commonly low scores on pain and disability measures (Table 2). As with the pain-based measures, however, no two were exactly alike. Ten studies asked subjects to fill in a single-item recovery rating scale [7, 10, 46, 53–55, 67, 77, 83, 96, 97, 102, 104, 105] (ranging from 4 to 15 points); nine variants of this scale were used in different studies (Table 3). Eleven studies used a global rating of change scale [9, 30, 42, 48, 52, 62–64, 76, 78, 84–86, 97, 98]; five variants of this scale were used. While the global rating of change scales was not designed to explicitly measure recovery, the scales include an anchor of ‘Completely Recovered’. Two studies used a dichotomous self-report measure of recovery, by directly asking patients whether or not they had recovered [8, 68]. Administrative data were used in four studies; two used return to work as the criterion [34, 35, 91], and two used time to insurance claim closure [14, 34, 35], and one further study used a self-rating of return to work [44] (Table 4). Six studies measured physical performance or absence of neurological deficits [4, 11, 29, 47, 74, 95], however in only three of these studies [4, 29, 47] was the test clearly described.

Table 2.

Combination measures

| Domains | Measure | Quantification | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coste [18] | Pain+ Disability |

VAS RMDQ |

≤20 mm on VAS ≤3 on RMDQ |

– |

| Dunn [24] | Pain+ Disability |

NRS RMDQ |

<1/10 on NRS <2 on RMDQ |

2 weeks |

| Secher Jensen [56] | Pain+ Disability |

Box scale for sciatic pain RMDQ |

0/10 on 11-box scale ≤3 on RMDQ |

2 weeks |

| Oberg [73] | Pain+ Disability |

VAS Oswestry |

≤10 mm on VAS ≤10% on Oswestry |

– |

| Cassidy [15] | Pain+ Disability |

CPQ | 0/4 (no pain) | – |

| Vingard [99] | Pain+ Disability |

Von Korff scale | ≤1/4 | 6 months |

| Skillgate [83] | Pain+ Disability |

Modified CPQ | Pain score ≤1 Disability score = 0 |

12 weeks |

| Niemisto [71] | Pain+ Disability |

Describedb | Not defined | – |

| Curtis [19] | Pain+ Disability |

Describedb | Patient’s assessment Able to perform daily activities as well as before this episode |

– |

| Henschke [44] | Pain+ Disability+ RTW |

SF-36 Item 7 SF-36 Item 8 RTW question |

0/6 (no LBP) 0/6 (no interfer. to normal work) RT previous work |

1 month |

| Beauvais [6] | Pain+ Disability+ RTW |

Describedb | Little or no analgesia, RT athletic activities, RT previous work | – |

| Dubourg [23] | Pain+ Phys perf. |

VAS Muscle strength |

≤20/100 mm or <50% of initial 4/5 on strength |

– |

| Guo [38] | Pain+ Phys perf. |

VRS Straight leg raise |

1/6 on VRS >70º on SLR |

– |

| Hollisaz [49] | Pain+ Phys perf. |

Describedb | Pain, paresthesia, reflexes, weakness resolved | – |

| Ferguson [27, 28]a | Pain+ Disability+ RTW+ Phys perf. |

McGill PQ Million VAS RTW Lumbar motion monitor |

Present pain index 0/5 MVAS <30/100 RTW—not defined LMM ≥0.5 |

– |

| Balague [3] | Pain+ Disability+ Phys perf. |

VAS Oswestry Muscle strength |

≤15 mm on VAS ≤20% on OSW 5/5 strength |

– |

RTW return to work, VAS visual analogue scale, RMDQ Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, NRS numerical rating scale, CPQ chronic pain questionnaire, OSW Oswestry disability questionnaire

aTwo studies published from the same cohort

bRecovery measure was not described in sufficient detail to enable replication

Table 3.

Self-ratings

| Study | Measure | Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| Whitman [102] | Recovery scale | 15-point Likert (dichotomized ≥ +3 improved) |

| Skillgate [83] | Recovery scale | 11-point (−5 to +5) |

| Jellema [53–55]a | Recovery scale | 7-point Likert (≤2 is recovered) |

| Peul [77] | Recovery scale | 7-point Likert (1 is completely recovered) |

| Bekkering [7]b, van der Roer [96]b | Recovery scale | 6-point Likert (≤2 is recovered) |

| Heymans [46] | Recovery scale | 6-point Likert (1 is completely recovered) |

| Mehling [67] | Recovery scale | 6-point recovery (6 is completely recovered) |

| Yip [104] | Recovery scale | 5-point rating of recovery (1 is completely recovered) |

| Yip [105] | Recovery scale | 5-point rating of recovery (1 is completely recovered) |

| Borman [10] | Recovery scale | 4-point rating of global recovery |

| Bernstein [8] | Question | Yes to: “completely better” |

| Mielenz [68] | Question | Yes to: “Completely better after this spell of back pain” |

| Heneweer [43] | Describedc | Recovery: yes/no |

| Pengel [76] | GPE scale | 11-point (−5 to +5) (+5 is completely recovered) |

| Ferreira [30] | GPE scale | 1-point (−5 to +5) (+5 is completely recovered) |

| Luijsterburg [62, 63]b | GPE scale | 7-point (1 is completely recovered) |

| Hildebrandt [48] | GPE scale | 7-point (1 is completely recovered) |

| Jans [52] | GPE scale | 7-point (1 is completely recovered) |

| Beurskens [9] | GPE scale | 7-point (1 is completely recovered) |

| Helmhout [42] | GPE scale | 7-point (1 is completely recovered) |

| Smeets [84–86]a | GPE scale | 7-point (7 is completely recovered) |

| Rattanatharn [78] | GPE scale | 6-point (1 is completely recovered) |

| van der Roer [97, 98]b | GPE scale | 6-point (1 is completely recovered) |

| Macfarlane [64] | GPE scale | 5-point (1 is completely recovered) |

GPE global perceived effect scale

aThree studies published from the same cohort

bTwo studies published from the same cohort

cRecovery measure was not described in sufficient detail to enable replication

Table 4.

Miscellaneous measures

| Study | Domain | Measure | Quantification | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hides [47] | Physical performance | US measurement of multifidus | Symmetry between CSA of L and R multifidi | – |

| Balague [4] | Physical performance | Isokinetic muscle test | Torque: involved mm/uninvolved mm = 0.85 | – |

| Ferguson [29] | Physical performance | Lumbar motion monitor | LMM ≥ 0.5 | – |

| Unlu [95] | Physical performance | Describedb | Return of reflexes | – |

| Ozturk [74] | Physical performance | Describedb | Return of reflexes | – |

| Brotz [11] | Physical performance | Describedb | Recovery from neurological deficits | – |

| Henschke [44] | RTW | Describedb | RT previous work status | 1 month |

| Gross [34, 35]a | RTW | Administrative data | Suspension of time-loss benefits | – |

| Steenstra [91] | RTW | Administrative data | Return to equal or own work | 1 month |

| Cassidy [14] | Insurance status | Administrative data | Time to claim closure | – |

| Gross [34, 35]a | Insurance status | Administrative data | Time to claim closure | – |

| Vroomen [100] | Unknown | Describedb | Not defined | – |

aTwo studies published from the same cohort

bRecovery measure was not described in sufficient detail to enable replication

Another aspect of recovery that varied widely among included studies is the duration for which patients had to meet the recovery criteria to be regarded as recovered. This feature was infrequently reported (in 18 out of 67 measures); one study based their measure on recall over 10 years, in all others the duration ranged from 1 week to 12 months.

Discussion

The principle finding of this review is the striking lack of consistency among measures of recovery from LBP. Of the 82 studies published in the last 10 years that measured recovery as an outcome, very few did so in exactly the same way. These data perhaps reflect the paucity of investigation into the concept of recovery from LBP [5, 51]. Irrespective of the reason, this lack of standardisation has important implications for the comparability and interpretation of the LBP literature.

Researchers assessed various related domains as surrogate measures of recovery, examples include; pain, disability and return to work, alone or in combination. The use of a range of domains reflects differing ideas among researchers as to how best to conceptualise recovery from LBP. For example, should the absence of pain denote recovery [17] or the absence of disability [44] or are both domains relevant [73]? Even when recovery is based on a single domain, e.g. pain, there remains the question of whether low levels of residual symptoms indicate recovery or complete absence of symptoms is necessary. Decisions regarding the domain, instrument and cut-off appear in most cases to have been made arbitrarily by researchers, perhaps because there is no uniform definition of recovery.

A range of methods were used to measure recovery, including: previously validated instruments, administrative/insurance data, or direct questions. There were also however a significant number of reports (more than 25% of measures) that provided only an imprecise description of their recovery criterion. Further, only a minority of studies reported the duration for which subjects must meet the specified criteria in order to be regarded as recovered. These findings highlight an important limitation in the recent literature; inadequate reporting of outcome measures provides a barrier to interpretability and comparability of research.

A number of studies assessed recovery via a single-item question, with either a dichotomous response or scored on a continuous/Likert scale anchored by ‘completely recovered’ or similar. A single-item measures may suffer from poorer reliability than multi-item measures [72] and there is also a conceptual obstacle in that it would seem unlikely that a complex process such as recovery can be adequately captured by a single-item measure. This method does however enable the researcher to assess the subject’s overall perspective of their recovery, ensuring relevance of the measure. This is in contrast to the approach outlined above, where the researchers determine what domains they regard as important in the subject’s recovery. Although this prescriptive approach offers advantages in terms of subject-to-subject comparability, the importance of incorporating patients’ views into outcome measurement has been increasingly recognised recently [5, 89, 94]. Research in this area suggests patients’ perspectives of recovery are idiosyncratic and often determined by individual appraisal of the impact of symptoms on daily activities and quality of life [51].

A relevant question is whether recovery should be considered a dichotomous or a continuous construct. Most of the included studies described recovery as dichotomous; dividing participants into exclusive categories of ‘recovered’ or ‘not recovered’ according to set criteria. On the other hand, several studies (see Table 3) used a recovery scale with between 4 and 14 points to place subjects along a recovery continuum. The former approach offers the advantage of simplicity for interpretation, but will almost certainly provide a less responsive measure of patient recovery. This consideration, along with their particular conceptualisation of recovery will direct researchers’ decision on what type of scale to use.

It is perhaps not surprising that wide variability exists in the measurement of recovery in LBP. Indeed, this situation is not uncommon in health-care research. Lack of standardised definitions for key terms and outcomes is noted in studies of whiplash-associated disorders [57], drowning [75], falls [41], spasticity [65], peptic ulcers [103] and schizophrenia [58]. This finding is likely due to the lack of a standardised measure for recovery as well as the absence of a clear and agreed-upon definition of what recovery from LBP means.

Limitations

It is possible that studies including definitions of recovery were missed by this review so we may have underestimated the variability in measurement of recovery. This would not influence the main finding of our study that there is a lack of consensus in this area.

Conclusion

This study highlights the lack of consistency among measures of recovery in LBP studies. Of the 66 different measures of recovery extracted, only 7 were used in more than one study. This variability is patently detrimental to the interpretability of the LBP literature. It is likely that the lack of an agreed definition for recovery from LBP contributes to this problem. Thus, it is recommended that efforts be directed toward formulating a definition, this step being a necessary precursor to selection or creation of a reliable and valid measure of recovery. Previous studies have used a Delphi process to arrive at a definition of various terms related to health-care research, e.g. complaints of the arm neck and shoulder [50], functional capacity evaluation [88], an episode of LBP [22]. An alternate method may be via a discussion process among experts in the area, e.g. outcome measures for chronic pain studies [25], disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis [1]. Development of a definition for recovery from LBP may be amenable to either of these processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank those that assisted with translation of the non-English language articles: Prof Rob Smeets, Ms Luciana Macedo, Dr Leo Costa, Dr Christine Lin and Mr Fred Zmudski. SJK’s scholarship and CGM’s fellowship are funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, TRS’s scholarship is funded by the University of Sydney.

Conflict of interest statement The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, Bathon J, Boers M, Bombadier C, Bombadieri S, Choi H, Combe B, Dougados M, Emery P. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59:1371–1377. doi: 10.1002/art.24123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakhtiar CS, Suneetha S, Vijay R. Conservative approaches benefit occupation-related backaches in milk-vendors and goldsmiths. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2002;6:186–188. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balague F, Nordin M, Sheikhzadeh A, Echegoyen AC, Brisby H, Hoogewoud HM, Fredman P, Skovron ML. Recovery of severe sciatica. Spine. 1999;24:2516–2524. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balague F, Nordin M, Sheikhzadeh A, Echegoyen AC, Skovron ML, Bech H, Chassot D, Helsen M. Recovery of impaired muscle function in severe sciatica. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:242–249. doi: 10.1007/s005860000226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaton DE, Tarasuk V, Katz JN, Wright JG, Bombadier C. Are you better? A qualitative study of the meaning of recovery. Arthritis Care Res. 2001;45:270–279. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)45:3<270::AID-ART260>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beauvais C, Wybier M, Chazerain P, Harboun M, Liote F, Roucoules J, Koeger AC, Bellaiche L, Orcel P, Bardin T, Ziza JM, Laredo JD. Prognostic value of early computed tomography in radiculopathy due to lumbar intervertebral disk herniation: a prospective study. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70:134–139. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(03)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekkering G, Hendriks H, Tulder MW, Knol D, Simmonds M, Oostendorp R, Bouter L. Prognostic factors for low back pain in patients referred for physiotherapy: comparing outcomes and varying modeling techniques. Spine. 2005;30:1881–1886. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000173901.64181.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein E, Carey TS, Garrett JM. The use of muscle relaxant medications in acute low back pain. Spine. 2004;29:1346–1351. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000128258.49781.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beurskens AJ, Vet HC, Koke AJ, Lindeman E, Heijden GJ, Regtop W, Knipschild PG. A patient-specific approach for measuring functional status in low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:144–148. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(99)70127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borman P, Keskin D, Bodur H. The efficacy of lumbar traction in the management of patients with low back pain. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23:82–86. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brotz D, Kuker W, Maschke E, Wick W, Dichgans J, Weller M. A prospective trial of mechanical physiotherapy for lumbar disk prolapse. J Neurol. 2003;250:746–749. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burton AK, McClune TD, Clarke RD, Main CJ. Long-term follow-up of patients with low back pain attending for manipulative care: Outcomes and predictors. Man Ther. 2004;9:30–35. doi: 10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey TS, Garrett JM. The relation of race to outcomes and the use of health care services for acute low back pain. Spine. 2003;28:390–394. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200302150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Coto P, Berglund A, Nygren A. Low back pain after traffic collisions: a population-based cohort study. Spine. 2003;28:1002–1009. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200305150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassidy JD, Cote P, Carroll LJ, Kristman V. Incidence and course of low back pain episodes in the general population. Spine. 2005;30:2817–2823. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000190448.69091.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Hogg-Johnson S, Smith P. The recovery patterns of back pain among workers with compensated occupational back injuries. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:534–540. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.029215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins DL, Evans JM, Grundy RH. The efficiency of multiple impulse therapy for musculoskeletal complaints. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:162e1–162e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coste J, Lefrancois G, Guillemin F, Pouchot J. Prognosis and quality of life in patients with acute low back pain: insights from a comprehensive inception cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2004;51:168–176. doi: 10.1002/art.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis P, Carey TS, Evans P, Rowane MP, Garrett JM, Jackman A. Training primary care physicians to give limited manual therapy for low back pain. Spine. 2000;25:2954–2961. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis P, Carey TS, Evans P, Rowane MP, Jackman A, Garrett J. Training in back care to improve outcome and patient satisfaction. J Fam Prac. 2000;49:786–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson L, Lawless M, Leary F. Concepts of recovery: competing or complementary. Curr Opin Psychiatr. 2005;18:664–667. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000184418.29082.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dionne CE, Dunn KM, Croft PR, Nachemson AL, Buchbinder R, Walker BF, Wyatt M, Cassidy JD, Rossignol M, Leboeuf-Yde C, Hartvigsen J, Lein-Arjas P, Latza U. A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine. 2008;33:95–103. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e7f94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubourg G, Rozenberg S, Fautrel B, Valls-Bellec I, Bissery A, Lang T, Faillot T, Duplan B, Briancon D, Levy-Weil F, Morlock G, Crouzet J, Gatfosse M, Bonnet C, Houvenagel E, Hary S, Brocq O, Poiraudeau S, Beaudreuil J, Sauverzac C, Durieux S, Levade MH, Esposito P, Maitrot D, Goupille P, Valat JP, Bourgeois P, Lurie JD. A pilot study on the recovery from paresis after lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2002;27:1426–1432. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200207010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn KM, Jordan K, Croft PR. Characterizing the course of low back pain: a latent class analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:754–761. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JS, Jensen MP, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Stucki G, Allen RR, Bellamy N, Carr DB, Chandler J, Cowan P. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elders LA, Burdorf A. Prevalence, incidence, and recurrence of low back pain in scaffolders during a 3-year follow-up study. Spine. 2004;29:E101–E106. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000115125.60331.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson SA, Marras WS, Gupta P. Longitudinal quantitative measures of the natural course of low back pain recovery. Spine. 2000;25:1950–1956. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson SA, Gupta P, Marras WS, Heaney C. Predicting recovery using continuous low back pain outcome measures. Spine J. 2001;1:57–65. doi: 10.1016/S1529-9430(01)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson SA, Marras WS. Revised protocol for the kinematic assessment of impairment. Spine J. 2004;4:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferreira M, Ferreira P, Latimer J, Herbert R, Hodges P, Jennings M, Maher C, Refshauge K. Comparison of general exercise, motor control exercise and spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low back pain: a randomized trial. Pain. 2007;131:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finneran MT, Mazanec D, Marsolais ME, Marsolais EB, Pease WS. Large-array surface electromyography in low back pain: a pilot study. Spine. 2003;28:1447–1454. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200307010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gheldof ELM, Vinck J, Vlaeyen JWS, Hidding A, Crombez G. Development of and recovery from short- and long-term low back pain in occupational settings: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:841–854. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giles LGF, Muller R. Chronic spinal pain: a randomized clinical trial comparing medication, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation. Spine. 2003;28:1490–1502. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200307150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gross DP, Battie MC. Functional capacity evaluation performance does not predict sustained return to work in claimants with chronic back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:285–294. doi: 10.1007/s10926-005-5937-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross DP, Battie MC. Work-related recovery expectations and the prognosis of chronic low back pain within a workers’ compensation setting. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:428–433. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000158706.96994.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grotle M, Brox JI, Veierod MB, Glomsrod B, Lonn JH, Vollestad NK. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: patients consulting primary care for the first time. Spine. 2005;30:976–982. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158972.34102.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grotle M, Brox JI, Glomsrod B, Lonn JH, Vollestad NK. Prognostic factors in first-time care seekers due to acute low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo W, Zhang H-J, Lin W-E. Effect of different acupuncture therapies in improving functional disturbance of waist and limbs in patients with multiple lumbar disc herniation at different stages. 2005;9:184–185. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hancock M, Maher C, Latimer J, McLachlan A, Cooper C, Day R, Spindler M, McAuley J. Assessment of diclofenac or spinal manipulative therapy, or both, in addition to recommended first-line treatment for acute low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1638–1643. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, Herbert RD, McAuley JH. Independent evaluation of a clinical prediction rule for spinal manipulative therapy: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:936–943. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0679-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hauer K, Lamb S, Jorstad E, Todd C, Becker C. Systematic review of definitions and methods of measuring falls in randomised controlled fall prevention trials. Age Ageing. 2006;35:5–10. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helmhout PH, Harts CC, Viechtbauer W, Staal JB, Bie RA. Isolated lumbar extensor strengthening versus regular physical therapy in an army working population with nonacute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1675–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heneweer H, Aufdemkampe G, Tulder MW, Kiers H, Stappaerts KH, Vanhees L. Psychosocial variables in patients with (sub)acute low back pain: an inception cohort in primary care physical therapy in the Netherlands. Spine. 2007;32:586–592. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000256447.72623.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, York J, Das A, McAuley JH. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:154–157. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, York J, Das A, McAuley JH. Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3072–3080. doi: 10.1002/art.24853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heymans MW, Vet HCW, Bongers PM, Knol DL, Koes BW, Mechelen W. The effectiveness of high-intensity versus low-intensity back schools in an occupational setting: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2006;31:1075–1082. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216443.46783.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hides JA, Jull GA, Richardson CA. Long-term effects of specific stabilizing exercises for first-episode low back pain. Spine. 2001;26:E243–E248. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hildebrandt V, Proper K, Berg R, Douwes M, Heuvel SG, Bluren S. Cesar therapy is temporarily more effective than a standard treatment from the general practitioner in patients with chronic aspecific lower back pain; randomized, controlled and blinded study with a I year follow-up. Ned Tidschr Geneesk. 2000;144:2258–2264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hollisaz M (2006) Use of electroacupuncture for treatment of chronic sciatic pain. Internet J Pain Symptom Control Palliative Care 5

- 50.Huisstede BMA, Miedema HS, Verhagen AP, Koes BW, Verhaar JAN. Multidisciplinary consensus on the terminology and classification of complaints of the arm, neck and/or shoulder. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:313–319. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.023861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hush J, Refshauge K, Sullivan G, Souza L, Maher C, McAuley J. Recovery: what does this mean to patients with low back pain. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61:124–131. doi: 10.1002/art.24162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jans MP, Korte EM, Heinrich J, Hildebrandt VH. Intermittent follow-up treatment with Cesar exercise therapy in patients with subacute or chronic aspecific low back pain: results of a randomized, controlled trial with a 1.5-year follow-up. Ned Tijdschr Fysiother. 2006;116:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jellema P, Windt DAWM, Horst HE, Twisk JWR, Stalman WAB, Bouter LM. Should treatment of (sub)acute low back pain be aimed at psychosocial prognostic factors? Cluster randomised clinical trial in general practice. BMJ. 2005;331:84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38495.686736.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jellema P, Horst HE, Vlaeyen JWS, Stalman WAB, Bouter LM, Windt DAW. Predictors of outcome in patients with (sub)acute low back pain differ across treatment groups. Spine. 2006;31:1699–1705. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000224179.04964.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jellema P, Roer N, Windt DAWM, Tulder MW, Horst HE, Stalman WAB, Bouter LM. Low back pain in general practice: cost-effectiveness of a minimal psychosocial intervention versus usual care. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1812–1821. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0439-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jensen TS, Albert HB, Sorensen JS, Manniche C, Leboeuf-Yde C. Magnetic resonance imaging findings as predictors of clinical outcome in patients with sciatica receiving active conservative treatment. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamper SJ, Rebbeck TJ, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M. Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2008;138:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelly M, Gamble C. Exploring the concept of recovery in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Mental Health Nurs. 2005;12:245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lake JK, Power C, Cole TJ. Back pain and obesity in the 1958 British birth cohort cause or effect? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:245–250. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:80–86. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Long A, Donelson R, Fung T. Does it matter which exercise? A randomized control trial of exercise for low back pain. Spine. 2004;29:2593–2602. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146464.23007.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luijsterburg P, Verhagen A, Ostelo R, Hoogen HJ, Peul WC, Avezaat CJ, Koes BW. Physical therapy plus general practitioners’ care versus general practitioners’ care alone for sciatica: a randomised clinical trial with a 12-month follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:509–517. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0569-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luijsterburg PA, Lamers LM, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, Hoogen HJ, Peul WC, Avezaat CJ, Koes BW. Cost-effectiveness of physical therapy and general practitioner care for sciatica. Spine. 2007;32:1942–1948. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31813162f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Macfarlane GJ, Thomas E, Croft PR, Papageorgiou AC, Jayson MIV, Silman AJ. Predictors of early improvement in low back pain amongst consulters to general practice: the influence of pre-morbid and episode-related factors. Pain. 1999;80:113–119. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malhotra S, Pandyan A, Jones P, Hermens H. Spasticity, an impairment that is poorly defined and poorly measured. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:651–658. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McGuirk B, King W, Govind J, Lowry J, Bogduk N. Safety, efficacy, and cost effectiveness of evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute low back pain in primary care. Spine. 2001;26:2615–2622. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mehling W, Hamel K, Acree M, Byl N, Hecht F. Randomized, controlled trial of breath therapy for patients with chronic low-back pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mielenz TJ, Garrett JM, Carey TS. Association of psychosocial work characteristics with low back pain outcomes. Spine. 2008;33:1270–1275. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817144c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell R, Carmen G. Results of a multicenter trial using an intensive active exercise program for the treatment of acute soft tissue and back injuries. Spine. 1990;15:514–521. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199006000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naguszewski WK, Naguszewski RK, Gose EE. Dermatomal somatosensory evoked potential demonstration of nerve root decompression after VAX-D therapy. Neurol Res. 2001;23:706–714. doi: 10.1179/016164101101199216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Niemisto L, Sarna S, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Lindgren K, Hurri H. Predictive factors for 1-year outcome of chronic low back pain following manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physician consultation or physician consultation alone. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36:104–109. doi: 10.1080/16501970310019151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Norman GR, Stratford P, Regehr G. Methodological problems in the retrospective computation of responsiveness to change: the lesson of Cronbach. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:869–879. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oberg B, Enthoven P, Kjellman G, Skargren E. Back pain in primary care: a prospective cohort study of clinical outcome and healthcare consumption. Adv Physiother. 2003;5:98–108. doi: 10.1080/14038190310004862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ozturk B, Gunduz O, Ozoran K, Bostanoglu S. Effect of continuous lumbar traction on the size of herniated disc material in lumbar disc herniation. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:622–626. doi: 10.1007/s00296-005-0035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Papa L, Hoelle R, Idris A. Systematic review of definitions for drowning incidents. Resuscitation. 2005;65:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pengel L, Refshauge K, Maher C, Nicholas M, Herbert R, McNair P. Physiotherapist-directed exercise, advice, or both for subacute low back pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:787–796. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peul WC, Brand R, Thomeer RTWM, Koes BW. Influence of gender and other prognostic factors on outcome of sciatica. Pain. 2008;138:180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rattanatharn R, Sanjaroensuttikul N, Anadirekkul P, Chaivisate R, Wannasetta W. Effectiveness of lumbar traction with routine conservative treatment in acute herniated disc syndrome. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:S272–S277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reigo T, Tropp H, Timpka T. Clinical findings in a population with back pain. Relation to one-year outcome and long-term sick leave. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:208–214. doi: 10.1080/028134300448760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roberts G, Wolfson P. The rediscovery of recovery: open to all. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10:37–49. doi: 10.1192/apt.10.1.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schattenkirchner M, Milachowski KA. A double-blind, multicentre, randomised clinical trial comparing the efficacy and tolerability of aceclofenac with diclofenac resinate in patients with acute low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schiottz-Christensen B, Nielsen GL, Hansen VK, Schodt T, Sorensen HT, Olesen F. Long-term prognosis of acute low back pain in patients seen in general practice: a 1-year prospective follow-up study. Fam Prac. 1999;16:223–232. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Skillgate E, Vingard E, Alfredsson L. Naprapathic manual therapy or evidence-based care for back and neck pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:431–439. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31805593d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smeets R, Vlaeyen J, Hidding A, Kester A, Heijden GJ, Geel AC, Knottnerus J. Active rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cognitive-behavioral, physical, or both? First direct post-treatment results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskel Disorder. 2006;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Smeets R, Beelen S, Goossens M, Schouten E, Knottnerus J, Vlaeyen J. Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with the outcome of both physical and cognitive–behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:305–315. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318164aa75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smeets R, Vlaeyen J, Hidding A, Kester AD, van der Heijden GJ, Knottnerus JA. Chronic low back pain: physical training, graded activity with problem solving training, or both? The one-year post-treatment results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2008;134:263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smith BH, Elliott AM, Hannaford PC, Chambers WA, Smith WC. Factors related to the onset and persistence of chronic back pain in the community: results from a general population follow-up study. Spine. 2004;29:1032–1040. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Soer R, Schans CP, Groothoff JW, Geertzen JHB, Reneman MF. Towards consensus in operational definitions in functional capacity evaluation: a Delphi survey. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10926-008-9155-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sonke G, Verbeek A, Kiemeney L. A philosophical perspective supports the need for patient-outcome studies in diagnostic test evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stanton TR, Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, McAuley JH. After an episode of acute low back pain, recurrence is unpredictable and not as common as previously thought. Spine. 2008;33:2923–2928. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818a3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Steenstra IA, Anema JR, Bongers PM, Vet HC, Knol DL, Mechelen W. The effectiveness of graded activity for low back pain in occupational healthcare. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:718–725. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.021675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stig L, Nilsson O, Leboeuf-Yde C. Recovery pattern of patients treated with chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for long-lasting or recurrent low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:288–291. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.114362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tubach F, Beaute J, Leclerc A. Natural history and prognostic indicators of sciatica. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:174–179. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Revicki D, Harding G, Burke LB, Cella D, Cleeland CS, Cowan P, Farrar JT, Hertz S, Max MB, Rappaport BA. Identifying important outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: an IMMPACT survey or people with pain. Pain. 2008;137:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Unlu Z, Tasci S, Tarhan S, Pabuscu Y, Islak S. Comparison of 3 physical therapy modalities for acute pain in lumbar disc herniation measured by clinical evaluation and magnetic resonance imaging. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roer N, Ostelo RWJ, Bekkering GE, Tulder MW, Vet HCW. Minimal clinically important change for pain intensity, functional status, and general health status in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Spine. 2006;31:578–582. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000201293.57439.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Roer N, Tulder M, Mechelen W, Vet H. Economic evaluation of an intensive group training protocol compared with usual care physiotherapy in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 2008;33:445–451. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318163fa59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Roer N, Tulder M, Barendse J, Knol D, Mechelen W, Vet H. Intensive group training protocol versus guideline physiotherapy for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1193–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vingard E, Mortimer M, Wiktorin C, Pernold G, Fredriksson K, Nemeth G, Alfredsson L. Seeking care for low back pain in the general population. A two-year follow-up study: results from the MUSIC-Norrtalje study. Spine. 2002;27:2159–2165. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200210010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vroomen PC, Krom MC, Wilmink JT, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA. Lack of effectiveness of bed rest for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:418–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Waxman R, Tennant A, Helliwell P. A prospective follow-up study of low back pain in the community. Spine. 2000;25:2085–2090. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Whitman J, Flynn T, Childs J, Wainner R, Gill H, Ryder M, Garber M, Bennett A, Fritz J. A comparison between two physical therapy treatment programs for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2006;31:2541–2549. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000241136.98159.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yeomans N, Naesdal J. Systematic review: ulcer definition in NSAID ulcer prevention trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yip Y, Tse S. The effectiveness of relaxation acupoint stimulation and acupressure with aromatic lavender essential oil for non-specific low back pain in Hong Kong: a randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yip Y, Tse H, Wu K. An experimental study comparing the effects of combined transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation and electromagnetic millimeter waves for spinal pain in Hong Kong. Complement Ther Clin Prac. 2007;13:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]