Abstract

Expressed sequence tag (EST) markers have been used to assess variety and genetic diversity in wheat (Triticum aestivum). In this study, 1549 ESTs from wheat infested with yellow rust were used to examine the genetic diversity of six susceptible and resistant wheat cultivars. The aim of using these cultivars was to improve the competitiveness of public wheat breeding programs through the intensive use of modern, particularly marker-assisted, selection technologies. The F2 individuals derived from cultivar crosses were screened for resistance to yellow rust at the seedling stage in greenhouses and adult stage in the field to identify DNA markers genetically linked to resistance. Five hundred and sixty ESTs were assembled into 136 contigs and 989 singletons. BlastX search results showed that 39 (29%) contigs and 96 (10%) singletons were homologous to wheat genes. The database-matched contigs and singletons were assigned to eight functional groups related to protein synthesis, photosynthesis, metabolism and energy, stress proteins, transporter proteins, protein breakdown and recycling, cell growth and division and reactive oxygen scavengers. PCR analyses with primers based on the contigs and singletons showed that the most polymorphic functional categories were photosynthesis (contigs) and metabolism and energy (singletons). EST analysis revealed considerable genetic variability among the Turkish wheat cultivars resistant and susceptible to yellow rust disease and allowed calculation of the mean genetic distance between cultivars, with the greatest similarity (0.725) being between Harmankaya99 and Sönmez2001, and the lowest (0.622) between Aytin98 and Izgi01.

Keywords: biodiversity, EST, genetic diversity, Triticum, yellow rust

Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important crops in the world and is grown in all agricultural regions of Turkey. The total area cultivated worldwide and in Turkey is 210 and 9.4 million ha, respectively (Zeybek and Yigit, 2004). The allohexaploid wheat genome (2n = 6x = 42) is one of the largest among crop species, with a haploid size of 16 billion bp (Bennett and Leitch, 1995), and its genetics and genome organization have been extensively studied using molecular markers (Yu et al., 2004; Ercan et al., 2010; Akfirat-Senturk et al., 2010).

PCR-based molecular markers such as simple sequence repeats (SSR) (Plaschke et al., 1995), restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (Nagaoka and Ogihara, 1997), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (Gülbitti-Onarici et al., 2007), selective amplification of microsatellite polymorphic loci (SAMPL) (Altintas et al., 2008) and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (Asif et al., 2005) are easy to use and show a high degree of polymorphism. A number of wheat genetic maps have been constructed using PCR based markers (Li et al., 2007).

In recent year, expressed-sequence tags (ESTs) have become a valuable tool for genomic analyses and are currently the most widely used approach for sequencing plant genomes, both in terms of the number of sequences and total nucleotide counts (Rudd, 2003). EST analysis provides a simple strategy for studying the transcribed regions of genomes, and renders complex, highly redundant genomes such as that of wheat amenable to large-scale analysis. The number of ESTs and cDNA sequences in public databases such as GenBank has increased exponentially in recent few years, and EST-based markers have been used to distinguish varieties and assess genetic diversity in wheat (Kantety et al., 2002; Leigh et al., 2003).

Yellow rust, a destructive disease of wheat triggered by the biotrophic fungus Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Chen 2005), is the most frequent and important cereal disease in Turkey, where it causes grain yield losses of 40%-60% and lowers the quality of cereal products (Zeybek and Yigit, 2004). In this study, an EST database for yellow rust-infested wheat was used, in conjunction with a multi-variate statistical package (MVSP v.3.1), to assess the genetic diversity of yellow rust resistant and susceptible wheat genotypes. For this, EST sequences were assembled into longer contiguous sequences (contigs) using Vector NTI 10.0 software. Difficulties related to sequencing errors and the determination of orthology associated with the use of ESTs for systematics can be minimized by using several reads to assemble contigs and EST clusters for each region (Parkinson et al., 2002; Torre et al., 2006). The knowledge gained about the genetic constitution and relationships of genotypes using this approach should prove useful in the optimization of wheat breeding programs.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and evaluations

Six homozygous bread wheat genotypes (three yellow rust-resistant cultivars: PI178383, Izgi01, Sönmez2001, and three yellow rust-susceptible cultivars: Harmankaya99, ES14, Aytin98) were obtained from the Anatolian Agricultural Research Institute, Eskisehir, Turkey. The resistance of the parental cultivars and F2 generation was tested in greenhouses by applying uredospores. Two weeks after the inoculation the infection was scored on a scale of 0-9 (McNeal et al., 1971), with scores of 0-6 indicating a low infection and 7-9 indicating a high infection. The disease score for PI178383, Izgi01 and Sönmez2001 was 0 while that of Harmankaya99, ES14 and Aytin98 was 8, this confirming the resistance and susceptibility of the parental genotypes.

Analysis of wheat yellow rust ESTs

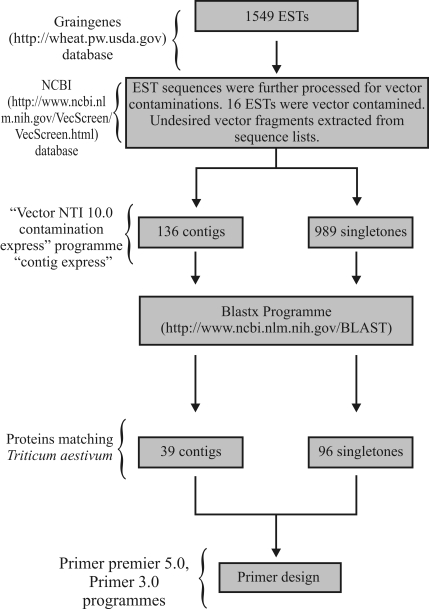

ESTs from a yellow rust-infected wheat cDNA library (TA117G1X) were selected from the GrainGenes website and processed by means of VecScreen database searches to remove undesired vector fragments from the sequences. The Vector NTI 10.0 contig express program (InforMax, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to construct contig tags from the EST sequences and the Contig Express module was used to assemble small fragments in text or chromatogram formats into contigs (Lu and Moriyama, 2004). Singletons were constructed from unassembled ESTs. The EST sequences were aligned and analyzed with ClustalW v.1.82 to identify conserved domains. Functional annotation was done using the BlastX algorithm of the Basic Alignment Search Tool (Altschul et al., 1990). PCR primers for the contigs and singletons selected for further characterization were designed with Primer Premier 5.0 and Primer 3.0 software (Figure 1). EST-derived contig and singleton primers were used to assess the genetic diversity of the six wheat genotypes.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the strategy for using the EST database and exploiting contigs and singletons.

PCR analyses of contigs and singletons

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of resistant and susceptible plants using the method of Weining and Langridge (1991) as modified by Song and Henry (1995). Genomic DNA amplifications with sense and antisense primers were done using a PTC-100 MJ thermocycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA) in a 25 μL reaction volume. Each reaction contained 1X Taq buffer (MBI Fermentas, Germany), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (MBI Fermentas), 0.2 mM dNTP (MBI Fermentas), 400 nM of forward primer, 400 nM of reverse primer, 0.625 U of Taq polymerase/μL (MBI Fermentas) and 100 ng of genomic DNA. The thermal cycling parameters were: 3 min at 94 °C (initial denaturation), 37 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 40-58 °C (depending on the annealing temperature) and 1 min at 72 °C, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and examined under UV light.

Genetic similarity estimation and cluster analyses

Each contig and singleton band was scored as absent (0) or present (1) for the different cultivars and the data were entered into a binary matrix as discrete variables (‘1' for presence and ‘0' for absence of a homologous fragment). Only distinct, reproducible, well-resolved fragments were scored and the data were analyzed using MVSP 3.1 software (Kovach, 1999). This software package was also used to calculate Jaccard (1908) similarity coefficients to construct a dendrogram by a neighbour-joining algorithm.

Results

Assembly of contigs and blast analysis

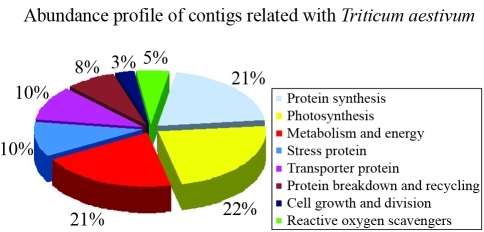

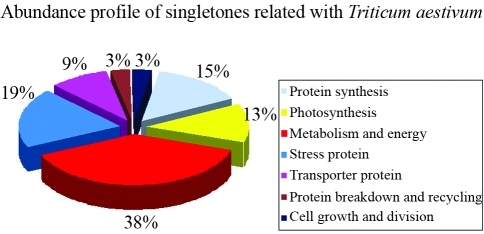

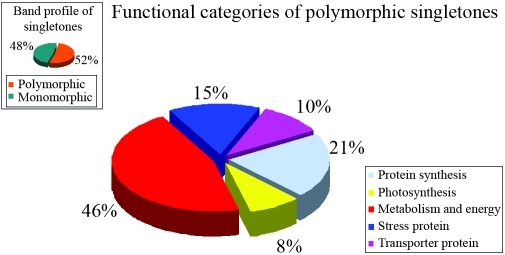

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the database used in this analysis. 1549 ESTs were selected from a yellow rust-infested wheat cDNA library (TA117G1X) and used to assemble 136 contigs. The number of individual ESTs belonging to each contig ranged from 2 to 57. Singletons were derived from unassembled ESTs and accounted for 72.63% of ESTs. Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the NCBI database searches done using the contig and singleton sequences. The BlastX searches revealed that 39 contigs (29%) were homologous to wheat genes (Figure 2). Contigs 3, 4, 11, 13, 16 and 112 did not match any organism. Contig 77 matched a sequence of unknown function (data not shown) while other contigs (71%) showed homology to genes of known function. The BlastX search also showed that 96 singletons (10%) were homologous to wheat genes (Figure 3), whereas 147 singletons (14%) did not match any organism and had no functional annotation (data not shown). The 39 contigs and 96 singletons that matched wheat proteins were assigned to eight functional groups that included protein synthesis, photosynthesis, metabolism and energy, stress proteins, transporter proteins, protein breakdown and recycling, cell growth and division and reactive oxygen scavengers. Photosynthesis was the major functional category of contigs, with nine proteins (22%), whereas cell growth and division was the smallest, with one protein (3%) (Figure 2). Metabolism was the major functional category of singletons, with 37 proteins (38%), whereas protein breakdown and recycling and cell growth and divison were the smallest functional categories, with three proteins (3%) (Figure 3). Tables 4 and 5 show the sense and antisense primers used to assess the genetic diversity of wheat cultivars; these primers were designed based on the contig and singleton sequences that were homologous to wheat genes.

Table 1.

General characteristics of ESTs from yellow rust-infested wheat (Triticum aestivum).

| Database characteristics | |

| Library name | TA117G1X |

| Stage | - |

| Total number of ESTs | 1,549 |

| Contigs | 136 |

| Total contig size (bp) | 80,241 |

| Unigenes | 1,125 (72.6%) |

| EST contigs | 560 |

| Singletons | 989 (63.8%) |

| Contaminated ESTs | 16 |

Table 2.

Contigs that showed homology to genes with proteins matching Triticum aestivum identified in a BlastX search of the NCBI database.

| Contig name | Blast hit number | Annotation | Accession number |

| Contig 1 | 100 | ribosomal protein L16 | NP_114295 |

| Contig 8 | 44 | ribosomal protein S7 | AAW50993 |

| Contig 9 | 101 | lipid transfer protein | ABB90546 |

| Contig 12 | 101 | chlorophyll a/b binding protein, chloroplast precursor (LHCII type I CAB) (LHCP) | P04784 |

| Contig 17 | 100 | ferredoxin, chloroplast precursor | P00228 |

| Contig 19 | 100 | triosephosphate-isomerase | CAC14917 |

| Contig 21 | 196 | putative glycine decarboxylase subunit | AAM92707 |

| Contig 22 | 281 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A1 | AAZ95171 |

| Contig 24 | 100 | single-stranded nucleic acid binding protein | AAA75104 |

| Contig 30 | 100 | cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | AAP83583 |

| Contig 33 | 294 | chlorophyll a/b-binding protein WCAB precursor [Triticum aestivum] | AAB18209 |

| Contig 34 | 65 | jasmonate-induced protein | AAR20919 |

| Contig 35 | 44 | oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 2, chloroplast precursor (OEE2) | Q00434 |

| Contig 39 | 100 | geranylgeranyl hydrogenase | AAZ67145 |

| Contig 40 | 100 | chlorophyll a/b-binding protein WCAB precursor | AAB18209 |

| Contig 46 | 102 | chlorophyll a/b-binding protein WCAB precursor | AAB18209 |

| Contig 49 | 31 | oxygen-evolving complex precursor | AAP80632 |

| Contig 52 | 9 | metallothionein-like protein 1 (MT-1) | P43400 |

| Contig 55 | 198 | glycine-rich RNA-binding protein | BAF30986 |

| Contig 57 | 100 | type 1 non-specific lipid transfer protein precursor | CAH04983 |

| Contig 58 | 33 | RUB1-conjugating enzyme | AAP80608 |

| Contig 63 | 103 | oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 1, chloroplast precursor (OEE1) (33 kDa subunit of oxygen evolving system of photosystem II) (OEC 33 kDa subunit) (33 kDa thylakoid membrane protein) | P27665 |

| Contig 65 | 101 | acidic ribosomal protein P2 | AAP80619 |

| Contig 66 | 199 | cyclophilin A-1 | AAK49426 |

| Contig 73 | 190 | dehydroascorbate reductase | AAL71854 |

| Contig 75 | 63 | metallothionein | AAP80616 |

| Contig 80 | 33 | wali7 | AAC37416 |

| Contig 90 | 52 | putative membrane protein | ABB90549 |

| Contig 91 | 100 | cold shock protein-1 | BAB78536 |

| Contig 93 | 155 | Ps16 protein | BAA22411 |

| Contig 96 | 109 | elongation factor 1-alpha (EF-1-alpha) | Q03033 |

| Contig 99 | 72 | histone H1 WH1A.2 | AAD41006 |

| Contig 105 | 131 | ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase (EC 4.1.1.39) small chain precursor (clone pWS4.3) - wheat | RKWTS |

| Contig 110 | 82 | cytochrome b6-f complex iron-sulfur subunit, chloroplast precursor (Rieske iron-sulfur protein) (plastohydroquinone:plastocyanin oxidoreductase iron-sulfur protein) (ISP) (RISP) | Q7X9A6 |

| Contig 113 | 103 | lipid transfer protein 3 | AAP23941 |

| Contig 122 | 163 | ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase small subunit | BAB19814 |

| Contig 133 | 100 | ribosomal protein L36 | AAW50980 |

| Contig 135 | 100 | 60s ribosomal protein L21 | AAP80636 |

| Contig 136 | 100 | histone H2A.2.1 | P02276 |

Table 3.

Singletons showing homology to genes with proteins matching Triticum aestivum identified in a BlastX search of the NCBI database.

| Singleton name | Blast hit number | Annotation | Accession number |

| CA599282 | 199 | ATP synthase CF1 alpha subunit | NP_114256 |

| CA599218 | 88 | ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase small subunit | BAB19811 |

| CA598725 | 191 | ribosomal protein L14 | NP_114294 |

| CA597765 | 119 | RuBisCO large subunit-binding protein subunit alpha, chloroplast precursor (60 kDa chaperonin subunit alpha) (CPN-60 alpha) | P08823 |

| CA597760 | 100 | type 1 non-specific lipid transfer protein precursor | CAH69210 |

| CA597766 | 3 | aintegumenta-like protein | ABB90555 |

| CA597808 | 116 | geranylgeranyl hydrogenase | AAZ67145 |

| CA597830 | 100 | 14-3-3 protein | AAR89812 |

| CA597851 | 49 | plastid glutamine synthetase isoform GS2c | AAZ30062 |

| CA597983 | 100 | GRAB2 protein | CAA09372 |

| CA598020 | 103 | protein H2A.5 (wcH2A-2) | Q43213 |

| CA598034 | 100 | histone deacetylase | AAU82113 |

| CA598102 | 22 | WIR1A protein | Q01482 |

| CA598128 | 100 | probable light-induced protein | AAP80856 |

| CA598130 | 100 | tubulin beta-2 chain (beta-2 tubulin) | Q9ZRB1 |

| CA598143 | 172 | thioredoxin M-type, chloroplast precursor (TRX-M) | Q9ZP21 |

| CA598151 | 100 | lipid transfer protein precursor | AAG27707 |

| CA598174 | 200 | S28 ribosomal protein | AAP80664 |

| CA598181 | 110 | pathogenisis-related protein 1.2 | CAA07474 |

| CA598182 | 2 | pathogenisis-related protein 1.2 | CAA07474 |

| CA598187 | 98 | VER2 | BAA32786 |

| CA598196 | 1 | putative cytochrome c oxidase subunit | AAM92706 |

| CA598235 | 100 | plasma membrane intrinsic protein 1 | AAF61463 |

| CA598239 | 151 | triosephosphate translocator | AAK01174 |

| CA598244 | 14 | glycosyltransferase | CAI30070 |

| CA598256 | 100 | heat shock protein 80 | AAD11549 |

| CA598258 | 22 | fasciclin-like protein FLA26 | ABI95416 |

| CA598286 | 80 | elongation factor 1-beta (EF-1-beta) | P29546 |

| CA598296 | 106 | beta-1,3-glucanase precursor | AAD28734 |

| CA598314 | 11 | oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 2, chloroplast precursor (OEE2) | Q00434 |

| CA598347 | 114 | putative ribosomal protein S18 | AAM92708 |

| CA598359 | 198 | sucrose synthase type I | CAA04543 |

| CA598366 | 105 | receptor-like kinase protein | AAS93629 |

| CA598421 | 121 | ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase (EC 4.1.1.39) small chain precursor (clone pWS4.3) | RKWTS |

| CA598422 | 75 | wali5 | AAA50850 |

| CA598432 | 99 | ribosomal protein P1 | AAW50990 |

| CA598476 | 100 | LRR19 | AAK20736 |

| CA598485 | 100 | ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase | CAA25058 |

| CA598489 | 64 | histone H2A | AAB00193 |

| CA598518 | 157 | phosphoribulokinase; ribulose-5-phosphate kinase | CAA41020 |

| CA598523 | 100 | ribosomal protein L19 | AAP80858 |

| CA598557 | 79 | type 2 non-specific lipid transfer protein precursor | CAH69201 |

| CA598577 | 252 | ferredoxin, chloroplast precursor | P00228 |

| CA598584 | 258 | putative fructose 1-,6-biphosphate aldolase | CAD12665 |

| CA598630 | 101 | translationally-controlled tumor protein homolog (TCTP) | Q8LRM8 |

| CA598637 | 100 | histone H2A | AAB00193 |

| CA598672 | 100 | lipid transfer protein | ABB90546 |

| CA598674 | 100 | glutathione transferase F6 | CAD29479 |

| CA598677 | 100 | ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase small subunit | BAB19812 |

| CA598687 | 55 | wali6 | AAC37417 |

| CA598691 | 100 | type 1 non-specific lipid transfer protein precursor | CAH04983 |

| CA598694 | 45 | cold-responsive LEA/RAB-related COR protein | AF255053 |

| CA598700 | 195 | fructan 1-exohydrolase | CAD48199 |

| CA598719 | 24 | 50S ribosomal protein L9, chloroplast precursor (CL9) | Q8L803 |

| CA598755 | 100 | type 1 non-specific lipid transfer protein precursor | CAH69190 |

| CA598762 | 95 | cysteine synthase (O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase) (O-acetylserine (thiol)-lyase) (CSase A) (OAS-TL A) | P38076 |

| CA598818 | 100 | putative fructose 1,6-biphosphate aldolase | CAD12665 |

| CA598837 | 126 | glutathione S-transferase | AAD56395 |

| CA598848 | 167 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | AAW68026 |

| CA598850 | 42 | putative proteinase inhibitor-related protein | AAS49905 |

| CA598919 | 43 | ferredoxin-NADP(H) oxidoreductase | CAD30024 |

| CA599166 | 137 | cold acclimation induced protein 2-1 | AAY16797 |

| CA599172 | 135 | stress responsive protein | AAY44603 |

| CA599235 | 100 | beta-expansin TaEXPB3 | AAT99294 |

| CA599238 | 77 | oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 2, chloroplast precursor (OEE2) (23 kDa subunit of oxygen evolving system of photosystem II) (OEC 23 kDa subunit) (23 kDa thylakoid membrane protein) | Q00434 |

| CA599257 | 101 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | AAW68026 |

| CA599262 | 196 | histone H2A.2.1 | P02276 |

| CA599265 | 2 | phosphoglycerate kinase, chloroplast precursor | P12782 |

| CA599271 | 100 | ribosomal protein L18 | AAW50985 |

| CA599273 | 68 | outer mitochondrial membrane protein porin (voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein) (VDAC) | P46274 |

| CA599277 | 103 | putative SKP1 protein | CAE53885 |

| CA599285 | 154 | putative lipid transfer protein | ABB90547 |

| CA598802 | 100 | ribosomal protein L11 | AAW50983 |

| CA598930 | 100 | thioredoxin h | CAB96931 |

| CA598940 | 199 | cyc07 | AAP80855 |

| CA598941 | 298 | calcium-dependent protein kinase | ABY59005 |

| CA598949 | 100 | putative 40S ribosomal protein S3 | AAM92710 |

| CA598961 | 100 | ribosomal protein L13a | AAW50984 |

| CA598962 | 57 | reversibly glycosylated polypeptide | CAA77237 |

| CA598966 | 282 | MAP kinase | ABS11090 |

| CA598975 | 105 | (1,3;1,4) beta glucanase | CAA80493 |

| CA598980 | 31 | minichromosomal maintenance factor | AAS68103 |

| CA599013 | 100 | D1 protease-like protein precursor | AAL99044 |

| CA599015 | 17 | putative beta-expansin | BAD06319 |

| CA599032 | 114 | tonoplast intrinsic protein | ABI96817 |

| CA599049 | 41 | porphobilinogen deaminase | AAL12221 |

| CA599099 | 100 | gamma-type tonoplast intrinsic protein | AAD10494 |

| CA599101 | 100 | small GTP-binding protein | AAD28731 |

| CA599103 | 19 | pre-mRNA processing factor | AAY84871 |

| CA599107 | 82 | sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase, chloroplast precursor (sedoheptulose bisphosphatase) (SBPase) (SED(1,7)P2ase) | P46285 |

| CA599110 | 199 | ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain PWS4.3, chloroplast precursor (RuBisCO small subunit PWS4.3) | P00871 |

| CA599114 | 3 | metallothionein-like protein 1 (MT-1) | P43400 |

| CA599115 | 176 | type 1 non-specific lipid transfer protein precursor | CAH69199 |

| CA599119 | 5 | putative high mobility group protein | CAI64395 |

| CA599121 | 51 | putative proteinase inhibitor-related protein | AAS49905 |

| CA599135 | 257 | putative cellulose synthase | BAD06322 |

Figure 2.

Classification of contigs homologous to proteins of known function.

Figure 3.

Classification of singletons homologous to proteins of known function.

Table 4.

Contig primers used for genomic amplifications.

| Primer | Sequence (5'-3') | TaoC | Product size (bp) | Primer | Sequence (5'-3') | TaoC | Product size (bp) |

| Contig 1F Contig 1R |

ACA gAT AgA AgC Agg ACg AA AAg ggT TgA Agg AAT TAT TgT C |

50 | 370 | Contig 58F Contig 58R |

ggg CAA gAA gAA ggA AgA gg TgA ggg TTA ggg AAg ggA gA |

50 | 267 |

| Contig 8F Contig 8R |

CCT CCA CTT CgC TgC TCC CT gCT CCT ggT TgC CgT TCT CC |

53 | 168 | Contig 63F Contig 63R |

CAg ggA ggT CgC AAg CAA TCA ACC CAA CgT ACg CAT |

48 | 898 |

| Contig 9F Contig 9R |

CAA ACT CgA TAg ggA Tgg C gCT TgA TTT gCA TAT Tgg gAC |

50 | 340 | Contig 65F Contig 65R |

gCT gCC TAT CTg CTT gCT T CCT TTC TCC Agg gAC CTT T |

48 | 295 |

| Contig 12F Contig 12R |

ACg CAC ATC ggA CAC gC CAg CTC CCg gTT CTT gg |

53 | 336 | Contig 66F Contig 66R |

gCg CAT CgT gAT ggA gCT Tgg gAg CCT TTg TTg TTg g |

53 | 302 |

| Contig 17F Contig 17R |

gCC ACC TTC TCA gCC ACA TTC gCC ggA ACA CCA AAC |

49 | 366 | Contig 73F Contig 73R |

CTg gTT TgC TAC TCC Tgg T Tgg CAT CCT TTg TTC TTT C |

46 | 417 |

| Contig 19F Contig 19R |

gCg gCA ACT ggA AAT g AgC CCT TgA gCg gAg T |

50 | 350 | Contig 75F Contig 75R |

gAg ATg gAC gAg ggA gTg AA ATg ggg TCT CCC TTg TTC TT |

50 | 499 |

| Contig 21F Contig 21R |

gCC CTC AAg ATT TCA AgC Ag ggg TTT TCg gAC AgT TTT gA |

50 | 516 | Contig 80F Contig 80R |

gCC AAg gAg TgA ggA Agg TCg ATT CAC ggA ggA gCA |

50 | 412 |

| Contig 22F Contig 22R |

ggA CAC CgA TgA gCA CCA AAg TTg ggA ggT TTC Agg |

48 | 363 | Contig 90F Contig 90R |

gAT TCg CAT CgC AgC ACA gCg gTT AAA CAg ACC CAg T |

50 | 409 |

| Contig 24F Contig 24R |

ggT Tgg CTT CTC CTC CCC T CgA gCT TCC TTg CCg TTC A |

51 | 331 | Contig 91F Contig 91R |

TTT Tgg TCC TTC ggT TTC g TCC TCC Tgg TgC ggT gA |

55 | 248 |

| Contig 30F Contig 30R |

gTT gAT gAg gAC CTT gTT TC TTg TTC ggg ggT TTT ATT TT |

44 | 450 | Contig 93F Contig 93R |

TTC AgC gAg CAC ggC AAA g gAC ACA Agg ATg gAT ggg A |

49 | 307 |

| Contig 33F Contig 33R |

ATg TCC CTC TCC TCg ACC TT AgT ggA TCA CCT CgA gCT TC |

51 | 291 | Contig 96F Contig 96R |

CTg CTg CTg CAA CAA gAT g gTT CCA ATg CCA CCA ATC T |

48 | 302 |

| Contig 34F Contig 34R |

ACT TCC gCA gCC TgT ACC TT CCA ACA ATT AgC CCA CTC AC |

53 | 302 | Contig 99F Contig 99R |

gCA TCT CCC CTC gAT TCC TA CgA CCC CgC TCT TCT CCT TC |

51 | 250 |

| Contig 35F Contig 35R |

CAA Tgg CgT CCA CCT CCT gC AgT CCg gTg ATg gTC TTC TTg g |

53 | 444 | Contig 105F Contig 105R |

CCg ATA ATA CAA TAC CAT TAC TCC TTT TTT gAC CTC |

40 | 434 |

| Contig 39F Contig 39R |

ggT gTT CTA CCg CTC CAA gAC gCC CAT TAC CCT TTT |

48 | 354 | Contig 110F Contig 110R |

CAT CTC gCT CCC CAC CTT TTT gCC CTT TgT TTg TTT |

40 | 356 |

| Contig 40F Contig 40R |

ACC CAC TAT ACC CAg gAg gC TCA gAA Cgg gAA gAA gCA gA |

51 | 338 | Contig 113F Contig 113R |

CAA AAA TAg CgT gCA Agg Tg TTg TTT CCA gTT Tgg TTg gA |

50 | 304 |

| Contig 46F Contig 46R |

gCA Agg Cgg TgA AgA ACg CCC TTT ggA CAg gAA CCC |

49 | 506 | Contig 122F Contig 122R |

AgC AAg gTT ggC TTC gTC CCg AgA ATT AAC AgC Agg AC |

50 | 474 |

| Contig 49F Contig 49R |

CTC gTg CCg AAg ACA gAA A CCC TCC CTT Tgg TTg gTT |

48 | 578 | Contig 133F Contig 133R |

CgT TAg CAg gAg CgA gTg gAg CAA ATC CAg CgA CCT |

49 | 196 |

| Contig 52F Contig 52R |

TTg ggT TCA CAg ATT Tgg Agg gAA gCA ATT AAC Agg gAC ACg |

50 | 432 | Contig 135F Contig 135R |

gCC gCA CAA gTT CTA CCA Cg ggA TTg ggA gTg ACg gTT CT |

51 | 311 |

| Contig 55F Contig 55R |

gAg TAC CgC TgC TTC gTC CCA CCT CCg CCA CTg AA |

53 | 286 | Contig 136F Contig 136R |

CAC CCA CTC CCA AAC CCT C gAT TTC AAg CAA gAA CCA A |

44 | 337 |

| Contig 57F Contig 57R |

CAC ggT TTC CAg CAA gCA TTg gCg TTC Agg gTC CTC |

50 | 227 |

Table 5.

Singleton primers used for genomic amplifications.

| Primer | Sequence (5'-3') | TaoC | Product size (bp) | Primer | Sequence (5'-3') | TaoC | Product size (bp) |

| CA598034F CA598034R |

AgC CTA AAA AAA AgC ATA Agg AgT CCC gTC AAA AAA |

38 | 418 | CA598930F CA598930R |

gTg gAC CAT gCA gAT CgA gg ggg ggC AAT TTT TAT TTT Ag |

46 | 366 |

| CA598174F CA598174R |

gAC CAA gAA CCg TCT CAT C TCA AgT CTC ACA ACA TCA A |

43 | 263 | CA598143F CA598143R |

gAT CAA gTg CTg CAA ggT gA TTg TTA TAA Cgg CgC ATC AA |

50 | 279 |

| CA598286F CA598286R |

gTT CTC CgA CCT CCA CAC gTC ATC ATC TTC ATC CTT |

42 | 278 | CA599110F CA599110R |

TCg gCT ACC ACC gTC gCA CC ACC CTC AAT Cgg CCA CAC CT |

58 | 138 |

| CA598347F CA598347R |

ggA ACg CAC CTC CTC CCC TC CCA gTC CCg gCA CCT TTg AA |

54 | 326 | CA599107F CA599107R |

Agg ACA CCA CgA gCA TC CCC CTT ggg AAC AgC Ag |

51 | 241 |

| CA598432F CA598432R |

CgC TgA AgA gAA gAA ggA CgC ATA ggA ggA ACC CAC |

47 | 122 | CA599218F CA599218R |

CCT CCT CTC CTC CgA TAA TA ACA TAg gCA gCT TTC CCA CA |

49 | 420 |

| CA598523F CA598523R |

ggA ggA ggA gAg Cgg Cgg C ATA TCC CAg gAg TgA ACg g |

50 | 262 | CA598196F CA598196R |

ggT CgT TTC gCT CTC CCC ATT TCT CCT CAg CTg gTT |

44 | 158 |

| CA598719F CA598719R |

gCC TCA TCC CCC TCC TCC Gc CgA TTC gCT CTT gCT TCC AC |

52 | 266 | CA599282F CA599282R |

gCg TAg TTC AAg Tgg ggg AAA AAT CAT TTA ggg ggg |

42 | 490 |

| CA598762F CA598762R |

ACg gCg ggA Tgg ggg Agg TTT gCT Tgg gAC gAT gAA |

44 | 224 | CA598296F CA598296R |

gCA CTg CTg gTg gAg ATg gTT Cgg ACg gAT TgA ggC |

50 | 278 |

| CA599271F CA599271R |

TCg gCA CgA ggg TAA gAA g AgT TTg gAg CAA Cgg gAg T |

49 | 483 | CA598421F CA598421R |

CTC CTC TCC TCC gAT AAT A TTg ACC TTC CCT CCC ACC T |

47 | 461 |

| CA598802F CA598802R |

gCT CgT CCT CAA CAT CTC TTT CAC CTT CAg gCC ACT | 50 | 214 | CA598485F CA598485R |

ACC gTT gCT gAC gCT gCC CCC CCA TTg TTC CCC ATT |

49 | 324 |

| CA598725F CA598725R |

CAg CgA TAT gCT CgT ATT gg CTC TCA ATT CCT Cgg CAA TC |

50 | 345 | CA598584F CA598584R |

CCC CTg Agg TgA TTg CTg TCg CCC TTg TAg gTg CCA |

50 | 306 |

| CA599103F CA599103F |

TgT CgT CTg CgT ATT ggT g Cgg ACT Tgg TgA CTT gCT A |

51 | 201 | CA598818F CA598818R |

TCC TTg CTg CCT gCT ACA TCC TCC ATT CTC Cgg TTC |

49 | 362 |

| CA598961F CA598961R |

ggA ggA AAA gAg gAA ggA TCA AAT gAg TgT CgC AgA |

48 | 272 | CA598677F CA598677R |

CgA CTA CCT TAT CCg CTC C ggg TTA CTC CCT TTT TTg A |

45 | 209 |

| CA598949F CA598949R |

gTT TgT gAg CgA Tgg CgT TT ATT gAC TTC AgC CTT Tgg gg |

51 | 324 | CA598518F CA598518R |

TCg gCA CgA ggg AgA AgC ATC ggA Agg Agg TAA AAC |

44 | 444 |

| CA597765F CA597765R |

TgA TTT CCT TTA TgC TTg Tg gCT TgT TgC TTg gTg ggg Tg |

44 | 234 | CA598700F CA598700R |

gAC TCC ATA CAA TCC CCA gCA CCC gTT TTT CCA CAT |

47 | 272 |

| CA598239F CA598239R |

ATT CAA CAT CCT CAA CAA gAA ACC CCC AAg gCA CCA |

40 | 372 | CA598975F CA598975R |

CgC AgT TAg CCA gAg AgA ggA gTT Tgg AgA gCA CgT |

51 | 298 |

| CA598314F CA598314R |

ATg gCg TCC ACC TCC TgC TT ggT Tgg TCg ggg TTT gAT TA |

50 | 466 | CA598244F CA598244R |

ggA gAT ggT Tgg TTg TgT T CCA ggg gTT gTT ggT AAA T |

50 | 378 |

| CA598577F CA598577R |

CgA CCT gCC CTA CTC TTg C AAC CCA CCT TgC CTC CAT T |

50 | 125 | CA599101F CA599101R |

CgT CgT CgC CAC AAg AgT T CgC CCg TgT TCC CCA gAT T |

55 | 363 |

| CA599238F CA599238R |

ggC gTC CAC CTC CTg CTT CC TTg TTg TTg ggg TTT gAT TA |

44 | 426 | CA597808F CA597808R |

CAC CTT CCT CCC TTC CTC CT CAT CTT TgT TgA CCC TCC TT |

48 | 308 |

| CA598919F CA598919R |

TAC TgA TTC TTg TgT CTT A CAC CCT TTA TCT ACT TTT A |

41 | 107 | CA598837F CA598837R |

gAg AgT gAg gAg TgA gAA gA AAA gCA TTA ggg ATT ggA TA |

44 | 436 |

| CA598848F CA598848R |

CCA gAT TTC CTT CCC CAT CAg CAC CAg CAg CAg CCC |

47 | 300 | CA598850F CA598850R |

ACg CCC AgC CCT CAC AAg A ACg gAC CCA CAC ACA AgC A |

51 | 189 |

| CA599257F CA599257R |

TgT TCT CAA CCT CCC CTC C CAA CgT ACT CAg CAC CCA g |

50 | 343 | CA599262F CA599262R |

CCC ACC CAC TCC CAA ACC CT CCg gCC AgC TCC AgC ACC TC |

56 | 266 |

| CA597851F CA597851R |

TTT ggA ggC ggC AgA gTA gTC ggT gAA ggg CgT ggT |

49 | 258 | CA598020F CA598020R |

gTC ACA TCA TCT TCT CCC T TCC CCA ACA TCA ACT CCg T |

47 | 185 |

| CA598130F CA598130R |

CTg ggA ggT ggT gTg TgA Tg ACT TTT TTg gTT gAg ggg AA |

46 | 482 | CA598235F CA598235R |

gCg AgA Agg AAC AgC AAg TTA gAC ggA CCA CgA Agg |

49 | 618 |

| CA598258F CA598258R |

CTC TCC CCC CCT CCC CAg gAg TTC ACC CCC gCC CCg |

57 | 338 | CA598359F CA598359R |

CCC TgC TgA AAT CAT TgT TAg TTg TCg gAg CTC TTg |

44 | 350 |

| CA598637F CA598637R |

CAC CTC gTg AgT CCT CgT Cg TgC ggg TCT TCT TgT TgT CC |

52 | 266 | CA598674F CA598674R |

AAg gTg CTg gAg gTC TAC AAT CAC ggC TTC TTg ggA |

47 | 230 |

| CA599135F CA599135R |

AAg gCg AAg AAg CCA ggT TT Tgg ATT ggA ggA TTg ggg AA |

53 | 292 | CA599114F CA599114R |

CCg Tgg TCg TCC TCg gCg Tg ggC AAT TAC Cgg ggg AAA CT |

55 | 334 |

| CA599099F CA599099R |

CTC ggA ggT gAg CgA AAA T gAC CCC CCC gTT gAg AAg C |

52 | 397 | CA599049F CA599049R |

ATT CTg CTC TgC TCC TCC CAg TTC gTC ACg ggT TTg |

51 | 278 |

| CA599032F CA599032R |

gCC gAT CCA TTC ATC CCg A AgC AgT TgC CCC ACC CAg T |

56 | 375 | CA599013F CA599013R |

TgA ACA AAg gAg ACA Cgg T TAT TgA TTg gAT TAA ggC C |

45 | 235 |

| CA598962F CA598962R |

CAg ggA Cgg TgA CTg TgC C AAT gTC gTT TgC ggT TgT A |

51 | 225 | CA598940F CA598940R |

gAC gCT CAA gCC CCC Ag Agg TTT gTT TgC CCA TA |

47 | 601 |

| CA599166F CA599166R |

Agg gCT CCT ATg CTT CgC gTT gTA CgC CgC TTg gTC |

54 | 211 | CA599172F CA599172R |

gCA gCC gAC ggT gAA gAt gAg ggC gTT gAA gTT TgA gTA g |

53 | 359 |

| CA597830F CA597830R |

CgT gAg AAC AgC gAA gCg gAT TgA TgC gAA CAT Agg C |

54 | 331 | CA597983F CA597983R |

TCA CgC ACT ACC TCA CCC CCC TTC CAg TAC CCT TTC T |

52 | 208 |

| CA598102F CA598102R |

ggC ACA gAC CCT AAC CAC gAg TAC ATT CAC ggA gAC g |

54 | 262 | CA598181F CA598181R |

CAC CCC gCA ggA CTT CgT TTT ATT TCC AgT TgA TTA |

36 | 382 |

| CA598187F CA598187R |

TAg TAT TCT CCC CgC CAC CAT CCT TTA ATT TTT TCA |

36 | 450 | CA598128F CA598128R |

gCC TTC TTg AAC CAT CCT g gCT TTg AAA TTT ggC gCC C |

49 | 451 |

| CA598256F CA598256R |

ggg CAT TgT TgA CTC TgA TTg TTC TCg gCA ATC TCA |

52 | 135 | CA598366F CA598366R |

CCC gTg gCA gTC AAg ATg TTg AAg CCC AAC Agg ATg |

54 | 347 |

| CA598422F CA598422R |

CAC gAg TgA AgT gAg AgC TAT TTT ATT TTA ggC ggA |

38 | 356 | CA598476F CA598476R |

ATT TCC CgA AgT TAg gCg CTC AAg ggC TgT AAg gTg |

52 | 160 |

| CA598630F CA598630R |

CAA AgC AAA TCC CAC AAT TgA ggC gTA ACA TCC AAg |

52 | 383 | CA598687F CA598687R |

gAg CAA gTT TAg gAg CgA CCA A ATg TAC ggg AAg gCg gAg C |

53 | 285 |

| CA598694F CA598694R |

AAT gTC Tgg CTg ggT TCA TCA gTC TTT CTT Tgg Tgg C |

52 | 352 | CA599121F CA599121R |

AAA CAA CCA TgA AgA ACA CC CAC ATC TAC gCA CAA AAA Cg |

48 | 370 |

| CA598966F CA598966R |

ggC TgT TTg AgA ATg gAC gg CTT Tgg TTT Tgg AgC ggg TT |

51 | 430 | CA598941F CA598941R |

CAT CAC CAA ggA ggA CA AAA gAA Cgg gAA gAg CC |

48 | 405 |

| CA597760F CA597760R |

gTg CTg gCg ATg gTg CTC gCC gTT Cgg ggT TgT TgT |

52 | 190 | CA598151F CA598151R |

gCg AgC CCT CCA CCA CAA Cgg CAA AgT AAT CAA TCA |

42 | 402 |

| CA598557F CA598557R |

ATg ggg AAg AAg CAg gTg g TTg gTT TgA ACA Agg AAg A |

43 | 441 | CA598672F CA598672R |

CAg Tgg gTg TCA ggA gTC T TgT gTT gTg TTg TgT TgT T |

43 | 375 |

| CA598691F CA598691R |

AAg CCg AAg CAC TAg ATC C ACA TTC CAg AAA AAC ACg A |

43 | 475 | CA598755F CA598755R |

AgC AAg CAA gCC gAA gCA CT Cgg gAA Agg AAA ACg gAg gA |

51 | 358 |

| CA599273F CA599273R |

gCA gCT CCA gCg gCg CAg gC gCg gTg TAg gTg gTA Agg gT |

54 | 146 | CA599285F CA599285R |

gCT CAC CAC CAC TAC TA ggA TgC CCg Cgg CCT TC |

46 | 319 |

| CA599115F CA599115R |

CgT gCg ggC Agg Tgg ACT TgA CAT gCT gAT ggg gAA |

52 | 252 | CA599235F CA599235R |

gAT ggC Tgg gCT ACT CTC T TTT ggA CCC CCg AAT TTT g |

47 | 461 |

| CA599277F CA599277R |

gCT TTT TTC CCC TTC CTC Cg gCC CCT TTg AAT CAA TgT CC |

50 | 552 | CA598980F CA598980R |

ATg AAC TgC TTC TgC TCC T TAg ATT TCg TAC TCT Tgg g |

47 | 255 |

| CA599015F CA599015R |

CCA TAT CCT CTC CCA AgC TCC CAC CCA TTC TCA AAC |

49 | 344 | CA599119F CA599119R |

CTC CCC AAA gCC CTA ACC AgC CAg gAA ggC gAA gAA g |

53 | 380 |

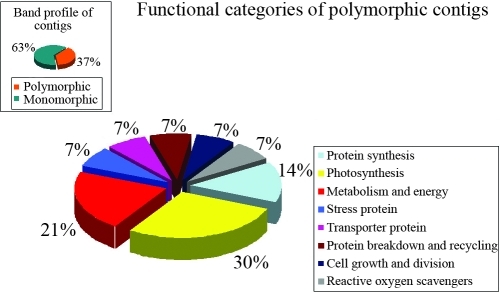

EST-derived contig and singleton polymorphisms

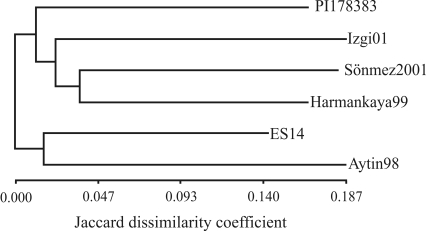

PCR analyses with the contig and singleton primers showed that the most polymorphic functional categories were photosynthesis (30%) and metabolism and energy (46%) for contigs and singletons, respectively (Figures 4 and 5). Of the 39 contig and 92 singleton primers used to characterize the genetic diversity of the six wheat genotypes, 14 contig and 48 singleton primers were polymorphic in susceptible and resistant wheat cultivars. Table 6 summarizes the mean genetic distance and genetic identity between the cultivars as determined by MVSP 3.1. Pairwise within-group distances ranged from 0 to 0.725, with the highest similarity (0.725) occurring between Harmankaya99 and Sönmez2001 and the lowest (0.622) between Aytin98 and Izgi01.

Figure 4.

Functional categories of polymorphic contigs.

Figure 5.

Functional categories of polymorphic singletons.

Table 6.

Similarity index (Jaccard's coefficient) between Triticum aestivum cultivars.

| Population ID | PI178383 | Izgi01 | Sönmez2001 | Harmankaya99 | ES14 | Aytin98 |

| PI178383 | 1.000 | |||||

| Izgi01 | 0.680* | 1.000 | ||||

| Sönmez2001 | 0.656* | 0.692* | 1.000 | |||

| Harmankaya99 | 0.692* | 0.680* | 0.725* | 1.000 | ||

| ES14 | 0.682* | 0.655* | 0.686* | 0.712* | 1.000 | |

| Aytin98 | 0.655* | 0.622* | 0.628* | 0.655* | 0.703* | 1.000 |

*Genetically similar.

Figure 6 shows the dendrogram based on the similarity index (Jaccard's coefficient) of the six cultivars. Two main clusters were observed, the first of which included cultivars Aytin98 and ES14 while the second was divided into two subclusters, the first of which comprised PI178383 while the second contained Izgi01, Sönmez2001 and Harmankaya99. The latter subcluster consisted a group containing Izgi01 and another containing Sönmez2001 and Harmankaya99. The construction of this dendrogram demonstrates the ability of EST-derived contigs and singletons in detecting extensive genetic diversity in genotypes with an expected narrow genetic pool.

Figure 6.

Dendrogram based on the genetic similarity of six Turkish bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes.

Discussion

Genome-marker technologies are particularly valuable for analyzing crops, such as wheat, that have relatively low levels of genetic diversity (Plaschke et al., 1995). DNA markers such as AFLP (Gülbitti-Onarici et al., 2007), RAPD (Asif et al., 2005), EST-SSR (Leigh et al., 2003), SSRs (Chen, 2005) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) (Zhang et al., 2002) are the most convenient data sources. EST databases represent a potentially valuable resource for developing molecular markers for evolutionary studies. Since EST-derived markers come from transcribed regions of the genome they are likely to be conserved across a broader taxonomic range than other types of markers (Pashley et al., 2006).

The low level of genetic diversity expected between self-pollinating plants means that EST databases can be useful tools for genetic studies in wheat and related species. Our results indicate that EST-derived primers were good tools for assessing the genetic diversity in wheat cultivars. A relatively high level of polymorphism (58.61% of loci were polymorphic) was observed with 39 contig and 92 singleton primers across the six wheat genotypes, despite the fact that all of them were local cultivars from geographically close locations. Several other studies have reported polymorphism in self-pollinating plants, including tef (4%) (Bai et al., 1999), azuki (18%) (Yee et al., 1999), rice (22%) (Maheswaran et al., 1997), sugar beet (50%) (Schondelmaier et al., 1996) and wild barley (76%) (Pakniyat et al., 1997). In a work similar to that reported here, Wei et al. (2005) used microsatellite markers to assess the polymorphic divergence in wheat landraces highly resistant to Fusarium head blight (FHB). The level of polymorphism observed among 20 wheat landraces resistant to FHB and four wheat landraces susceptible to FHB was 97.5% with a mean genetic similarity index among the 24 genotypes of 0.419 (range: 0.103 to 0.673).

In conclusion, we have used an EST database to examine the genetic diversity among Turkish wheat cultivars resistant and susceptible to yellow rust disease. Our results indicate that EST databases can be used to assess genetic diversity and identify suitable parents in populational studies designed to detect genes related to disease resistance.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Selma Onarici for her helpful comments, Dr. Necmettin Bolat for providing plant material and Central Research Institute of Field Crops for performing pathogenity tests. This study is a part of a PhD thesis (“Investigation of yellow rust disease resistance in winter-type bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using biotechnological methods”) by Ozge Karakas done at the Institute of Sciences and Research Foundation (project no. 1832), Istanbul University. This work was supported by TUBITAK KAMAG (project no. 105G075).

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Luciano da Fontoura Costa

References

- Akfrat-Senturk F., Aydn Y., Ertugrul F., Hasancebi S., Budak H., Akan K., Mert Z., Bolat N., Uncuoglu-Altnkut A. A microsatelite marker for yellow rust resistance in wheat. Cereal Research Communications. 2010;38:203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Altnta S., Toklu F., Kafkas S., Kilian B., Brandolini A., Özkan H. Estimating genetic diversity in drum and bread wheat cultivars from Turkey using AFLP and SAMPL markers. Plant Breed. 2008;127:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asf M., Rahman M.U., Zafar Y. DNA fingerprinting studies of some wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ) genotypes using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis. Pak J Bot. 2005;37:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Tefera H., Ayele M., Ngujen H.T. A genetic linkage map of tef [Eragrostis tef (Zucc. ) Trotter] based on amplified fragment length polymorphism. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;99:599–604. doi: 10.1007/s001220051274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M.D., Leitch I.J. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Ann Bot. 1995;76:113–176. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.M. Epidemiology and control of stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) on wheat. Can J Plant Pathol. 2005;27:314–337. [Google Scholar]

- Ercan S., Ertugrul F., Aydin Y., Akfirat-Senturk F., Hasancebi S., Akan K., Mert Z., Bolat N., Yorgancilar O., Uncuoglu-Altinkut A.A. An EST-SSR marker linked with yellow rust resistance in wheat. Biol Plant. 2010;5:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gülbitti-Onarici S., Sümer S., Özcan S. Determination of phylogenetic relationships between some wild wheat species using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers. Bot J Linn Soc. 2007;153:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard P. Nouvelles recherches sur la distribution florale. Bull Soc Vaud Sci Nat. 1908;44:223–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kantety R.V., Rota M.L., Matthews D.E., Sorrells M.S. Data mining for simple sequence repeats in expressed sequence tags from barley, maize, rice, sorghum and wheat. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:501–510. doi: 10.1023/a:1014875206165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach W.L. MVSP – A Multivariate Statistical Package for Windows, v. 3.1. Pentraeth: Kovach Computing Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh F., Lea V., Law J., Wolters P., Powell W., Donini P. Assessment of EST- and genomic microsatellite markers for variety discrimination and genetic diversity studies in wheat. Euphytica. 2003;133:359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Jia J., Wei X., Zhang X., Li L., Chen H., Fan Y., Sun H., Zhao X., Lei T., et al. An intervarietal genetic map and QTL analysis for yield traits in wheat. Mol Breed. 2007;20:167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lu G., Moriyama N.E. Vector NTI, a balanced all-in-one sequence analysis suite. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:378–388. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheswaran M., Subudhi P.K., Nandi S., Xu J.C., Parco A., Yang D.C., Huang N. Polymorphism, distribution and segregation of AFLP markers in doubled haploid rice population. Theor Appl Genet. 1997;94:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s001220050379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal F.M., Conzak C.F., Smith E.P., Tade W.S., Russell T.S. A uniform system for recording and processing cereal research data. US Agricultural Research Survice. 1971;42:34–121. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka T., Ogihara Y. Applicability of nter-simple sequence repeat polymorphisms in wheat for use as DNA markers in comparison to RFLP and RAPD markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1997;94:597–602. [Google Scholar]

- Pakniyat H., Powell W., Baird E., Handley L.L., Robinson D., Scrimgeour C.M., Nevo E., Hackett C.A., Caligari P.D.S., Forster B.P. AFLP variation in wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum C. Kock) with reference to salt tolerance and associated ecogeography. Genome. 1997;40:332–341. doi: 10.1139/g97-046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J., Guiliano D.B., Blaxter M. Making sense of EST sequences by CLOBBing them. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashley C.H., Ellis J.R., McCauley D.E., Burke J.M. EST databases as a source for molecular markers: Lessons from Helianthus. J Hered. 2006;97:381–388. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esl013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaschke J., Ganal M.W., Röder M.S. Detection of genetic diversity in closely related bread wheat using microsatellite markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1995;91:1001–1007. doi: 10.1007/BF00223912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd S. Expressed sequence tags: Alternative or complement to whole genome sequences? Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:321–328. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schondelmaier J., Streinrucken G., Jung C. Integration of AFLP markers into a linkage map of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. ) Plant Breed. 1996;115:231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Henry R.J. Molecular analysis of the DNA polymorphism of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) germplasm using the polymerase chain reaction. Genet Resourc Crop Evol. 1995;42:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Torre J., Egan M.G., Katari M.S., Brenner E.D., Stevenson D.W., Coruzzi G.M., DeSalle R. ESTimating plant phylogeny: Lessons from partitioning. BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y.M., Hou Y.C., Yan Z.H., Wu W., Zhang Z.Q., Liu D.C. Microsatellite DNA polymorphism divergence in Chinese wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ) landraces highly resistant to Fusarium head blight. J Appl Genet. 2005;46:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weining S., Langridge P. Identification and mapping of polymorphisms in cereals based on the polymerase chain reaction. Theor Appl Genet. 1991;82:209–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00226215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee E., Kidwell K.K., Sills G.R., Lumpkin T.A. Diversity among selected Vigna angularis (Azuki) accessions on the basis of RAPD and AFLP markers. Crop Sci. 1999;39:268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.K., Dake T.M., Singh S., Benscher D., Li W., Gill B., Sorrels M.E. Development and mapping of EST-derived simple sequence repeat markers for hexaploid wheat. Genome. 2004;47:805–818. doi: 10.1139/g04-057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeybek A., Yigit F. Determination of virulence genes frequencies in wheat stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) populations during natural epidemics in the regions of southern Aegean and western Mediterranean in Turkey. Pak J Biol Sci. 2004;7:1967–1971. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Qu L.J., Gu H., Gao W., Liu M. Studies on the origin and evolution of tetraploid wheats based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;104:1099–1106. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0887-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- GrainGenes. [August 15, 2007]. Available from: http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/cgi-bin/westsql/est_lib.cgi.

- VecScreen database. [September 20, 2007]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/VecScreen/VecScreen.html.

- ClustalW v.1.82. [November 22, 2007]. Available from: http://www.ebi.ac.uk.