Abstract

Muscle, motor unit and muscle fibre type-specific differences in force-generating capacity have been investigated for many years, but there is still no consensus regarding specific differences between slow- and fast-twitch muscles, motor units or muscle fibres. This is probably related to a number of different confounding factors disguising the function of the molecular motor protein myosin. We have therefore studied the force-generating capacity of specific myosin isoforms or combination of isoforms extracted from short single human muscle fibre segments in a modified single fibre myosin in vitro motility assay, in which an internal load (actin-binding protein) was added in different concentrations to evaluate the force-generating capacity. The force indices were the x-axis intercept and the slope of the relationship between the fraction of moving filaments and the α-actinin concentration. The force-generating capacity of the β/slow myosin isoform (type I) was weaker (P < 0.05) than the fast myosin isoform (type II), but the force-generating capacity of the different human fast myosin isoforms types IIa and IIx or a combination of both (IIax) were indistinguishable. A single fibre in vitro motility assay for both speed and force of specific myosin isoforms is described and used to measure the difference in force-generating capacity between fast and slow human myosin isoforms. The assay is proposed as a useful tool for clinical studies on the effects on muscle function of specific mutations or post-translational modifications of myosin.

Introduction

Myosin is the dominant contractile protein in skeletal muscle, and is considered to be the molecular motor that converts free energy derived from the hydrolysis of ATP into mechanical work. It is a hexamer composed of two myosin heavy chain (MyHC) subunits of approximately 220 kDa each and four myosin light chain (MyLC) subdivided into two regulatory and two essential MyLC, of approximately 20 kDa each. The MyHCs found in mammalian skeletal muscle myofibrils are all isoforms of the class II myosin family. To date, nine distinct MyHC isoforms have been identified in the striated muscles of mammals: β/slow (I), α-cardiac, slow-tonic, embryonic, fetal, IIa, IIx (IId), IIb, and extraocular super-fast. Three of these have been observed in normal adult human limb and trunk muscles: β/slow or type I, and the two fast MyHCs, IIa and IIx. There is a close relationship between the maximum velocity of unloading shortening (Vo), the actin-activated ATPase activity of myosin, and the myosin isoform expression of single muscle fibres in different species (Barany, 1967; Greaser et al. 1988; Larsson & Moss, 1993; Bottinelli et al. 1994; Schluter & Fitts, 1994; Li & Larsson, 1996; Reggiani et al. 1997). Slow-twitch fibres express the β/slow MyHC with a low ATPase activity, whereas fast fibres express fast MyHCs and have high ATPase activities. There is good evidence that different isoforms of myosin confer distinct contractile properties on muscle fibres. In turn, the contractile property of a motor unit or muscle is the results of the aggregate properties and myosin isoform content of its constituent fibres.

During the past few decades, the force-generating capacity of fast and slow myosin has been studied at the whole muscle, motor unit and muscle fibre levels. For whole muscle, higher tetanic tension, normalized to muscle weight, has been reported in the fast-twitch flexor digitorum longus (FDL) than in slow-twitch soleus (Kean et al. 1974); however, normalization of tetanus force to muscle weight does not take into account differences in muscle fibre architecture and the relative amount of non-contractile material. At the motor unit level, maximum force follows the order of fast-twitch fatigable (FF) ≥ fast-twitch fatigue-intermediate (FI) > fast-twitch fatigue-resistant (FR) > slow-twitch (S). Both size and number of muscle fibres are larger in fast- than in slow-twitch units; however, motor unit type-specific differences typically persist after normalizing maximum force to total muscle fibre cross-sectional area of glycogen-depleted motor unit fibres; furthermore, there is an overlap among the different fast-twitch types, but not between fast and slow-twitch units (Dum & Kennedy, 1980; Burke, 1981; Kanda & Hashizume, 1992; Rafuse et al. 1997). Because fast- and slow-twitch motor units are frequently from muscles with different architecture, differences in specific tension may be only apparent; even for comparison within the same muscle, such as rodent tibialis anterior muscle, fibres change orientation from the deep region containing slow-twitch motor units to the superficial region containing the fast-twitch units. At the single muscle fibre level, there is not a consensus concerning fibre type specific differences, and both similar specific force and fibre type-related (fast- stronger than slow-twitch) differences have been reported in skinned muscle fibres (Andruchov et al. 2004; Linari et al. 2004; Seebohm et al. 2009); at least in part, this may be due to secondary influences of structural and modulatory proteins at the single fibre level (Li & Larsson, 1996; Bottinelli, 2001; Sandercock, 2005).

In the present study, by modifying the single fibre myosin in vitro motility assay, we measured the force-generating capacity of specific myosin isoforms that were extracted from short single human muscle fibres. It is hypothesized that slow and fast myosin isoforms have reliably different force-generating capacity when the confounding factors at the muscle, motor unit and muscle fibre level have been eliminated. The modified assay is proposed as a useful tool for clinical studies on the effects on muscle function of specific mutations or post-translational modifications of myosin.

Methods

Muscle biopsies and fibre preparation

Muscle samples were obtained from the vastus lateralis and tibialis anterior of three healthy male adults (25, 29, and 35 years old) by using the percutaneous conchotome method. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Uppsala University and carried out according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from all subjects enrolled in the present study after they were fully informed of the aim for the experiments and of the risks involved in the biopsy procedure.

Bundles of approximately 50 fibres were dissected from the muscles in relaxing solution at 4°C and tied to glass capillaries, stretched to about 110% of their resting slack length. The bundles were chemically skinned by treatment for 24 h at 4°C in a relaxing solution containing 50% (v/v) glycerol, and then stored at −20°C. Within 1 week after skinning, the bundles were cryoprotected by transferring, at 30 min intervals, to relaxing solutions containing increasing concentrations of sucrose, (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 m), and then freezing in liquid propane chilled with liquid nitrogen. The frozen bundles were stored at −80°C. The day before an experiment, a bundle was transferred to a 2.0 m sucrose solution for 30 min and then incubated in solutions of decreasing sucrose concentration (1.5–0.5 m). The bundle was then stored in skinning solution at −20°C for up to 4 weeks.

Single fibre myosin in vitro motility assay

Unregulated actin was purified from rabbit skeletal muscle (Pardee & Spudich, 1982) and fluorescently labelled with rhodamine-phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The single fibre myosin in vitro motility system has been described in detail elsewhere (Hook et al. 1999; Hook & Larsson, 2000). In brief, a short muscle fibre segment (1–2 mm) was placed on a glass slide between two strips of grease, and a coverslip placed on top, creating a flow cell of ∼2 μl. Myosin was extracted from the fibre segment through addition of a high-salt buffer (0.5 m KCI, 25 mm Hepes, 4 mm MgCl2, 4 mm EGTA, pH adjusted to 7.6 before adding 2 mm ATP and 1%β-mercaptoethanol). After 30 min incubation on ice, a low-salt buffer (25 mm KCl, 25 mm Hepes, 4 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, pH adjusted to 7.6 before adding 1%β-mercaptoethanol) was applied, followed by BSA (1 mg ml−1). Non-functional myosin molecules were blocked with fragmentized F-actin, and rhodamine–phalloidin labelled actin filaments were subsequently infused into the flow cell, followed by motility buffer to initiate the movement (2 mm ATP, 0.1 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase, 23 μg ml−1 catalase, 2.5 mg ml−1 glucose and 0.4% methylcellulose in low-salt buffer). The pH of the buffers were adjusted with KOH, and the final ionic strength of the motility buffer was 71 mm. The flow cell was placed on the stage of an inverted epifluorescence microscope (model IX 70; Olympus) and thermostatically controlled at 25°C. Actin movements were filmed with an image-intensified SIT camera (SIT 66; DAGE-MTI, Michigan City, IN, USA) and recorded on video tape.

Modification of the motility assay for force measurement

The unit concentration (0.098 μg ml−1 in this study) of α-actinin (A9776, Sigma) dissolved in the low-salt buffer was chosen as the lowest concentration that would reduce the number of moving actin filaments. Multiples of this concentration were added to the flow cell over a fourfold range in the α-actinin concentration, i.e. from 0.098 to 0.392 μg ml−1. A specific area on the glass slide was defined by a UV-marking pen (Chr Winther-Sörensen AB, Knäred, Sweden) before creating the flow-cell. After identifying an organized moving filament, 3 μl α-actinin was applied to the flow-cell, incubated for 1 min, and followed by motility buffer. Moving filaments within the defined area, with constant myosin concentration, were recorded for 12 s to allow measurement of the number and speed of actin filaments at the different α-actinin concentrations, i.e. the duration was long enough for reliable measurements, but short enough to minimize the risk of photo-bleaching interference.

The linear decrease in the number of moving filaments and a fibre type specific difference in the force index represent indirect evidence of α-actinin binding to the surface. In addition, we have measured the amount of α-actinin on the surface in the experimental chamber after increasing the concentration of added α-actinin. The α-actinin concentration on the surface of the chamber normalized to the myosin content increased linearly with the increasing added α-actinin (data not shown).

The effects of temperature on force index and motility speed were studied in six muscle fibre preparations, i.e. the temperature in the flow cell was increased from 25°C to 30°C at the different α-actinin concentrations. Exposure to each temperature was approximately 1 min and the entire experiment was completed within 15 min. Video recordings were made when the actual temperature of the flow-cell was within ±0.2°C of the target temperature at 25°C, and within ±0.3°C at 30°C.

Motility speed analyses

For speed analysis, from each single fibre preparation, 20 actin filaments that were moving at constant speed in an oriented motion were selected. Recordings and analysis were only performed from preparations in which =90% of the filaments moved bi-directionally. A filament was tracked from the centre of mass, and the speed was calculated from 10 frames at an acquisition rate of 5 or 1 frame(s) per second, depending on the fibre type, using an image analysis package (Image-Pro Plus v. 6.0, Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) (Hook & Larsson, 2000; Ochala et al. 2008). The mean speed of the 20 filaments was calculated.

Force index analyses

Two force indices were used. First, the slope (regression coefficient, force indexslope) of the negative linear relationship between the relative fraction of moving filaments and α-actinin concentration, i.e. the number of moving filaments normalized to moving filaments prior to addition of α-actinin versus increasing α-actinin concentrations (the initial recording prior to adding α-actinin was omitted from the regression analyses since it may have a disproportional large impact on the regression line). Second, the x-axis intercept value of the regression line was also used as a force index (force indexintercept).

Myosin isoforms identification

After motility assay for force and speed measurements, each fibre segment was placed in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer in a plastic microfuge tube and stored at −80°C. The MyHC composition of a muscle fibre was determined by 6% SDS-PAGE. The acrylamide concentration was 4% (w/v) in the stacking gel and 6% in the running gel, and the gel matrix included 30% glycerol. Sample loads were kept small (equivalent to −0.05 mm of fibre segment) to improve the resolution of the MyHC bands (type I, IIa, and IIx). Electrophoresis was performed at 120 V for 24 h with a Tris-glycine electrode buffer (pH 8.3) at 15°C (SE 600 vertical slab gel unit, Hoefer Inc., Holliston, MA, USA). The gels were silver-stained and subsequently scanned in a soft laser densitometer (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with a high spatial resolution (50 μm pixel spacing) and 4096 optical density levels (Larsson & Moss, 1993). The volume integration function (ImageQuant software v. 3.3, Molecular Dynamics) was used to quantify the relative amount of each MyHC isoform when more than one isoform was expressed in the fibre segment.

Statistics

Means and standard deviations (s.d.) were calculated according to standard procedures. One-way ANOVA was used for between group comparisons when more than two groups of myosin isoforms were compared. Student's unpaired t test was used for comparisons between two groups. A paired t test was used when comparing the effects of the two different temperatures in the same preparation. Pearson product moment correlation was used to evaluate linear relations between the fraction of moving filaments and α-actinin concentration, and between force index and motility speed. Outliers were identified with Grubbs’ test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 30 fibres expressing the type I (n= 9), IIa (n= 10), IIax (n= 8) and IIx (n= 3) myosin isoform obtained from three healthy young male subjects fulfilled the acceptance criteria for both speed and force analysis and were included in the analyses. In addition, six fibres expressing the type I (n= 2), IIa (n= 2), IIax (n= 1) and IIx (n= 1) myosin isoform were included in the additional analyses of temperature effects. There were no differences between subjects within specific myosin isoforms and data have therefore been pooled.

Inhibitory effects of α-actinin

To create linear plots between the fraction of moving actin filaments and α-actinin concentration, five different α-actinin concentrations were used (0, 0.098, 0.195, 0.293 and 0.390 μg ml−1). The initial unit concentration of α-actinin (0.098 μg ml−1) was chosen as the lowest concentration that would produce detectable inhibition compared with α-actinin free solution. The fraction of moving filaments decreased progressively after exposure to the four α-actinin concentrations (see below); however, the speed of the filaments was not affected by the α-actinin concentration (data not shown).

Force index of specific myosin isoforms

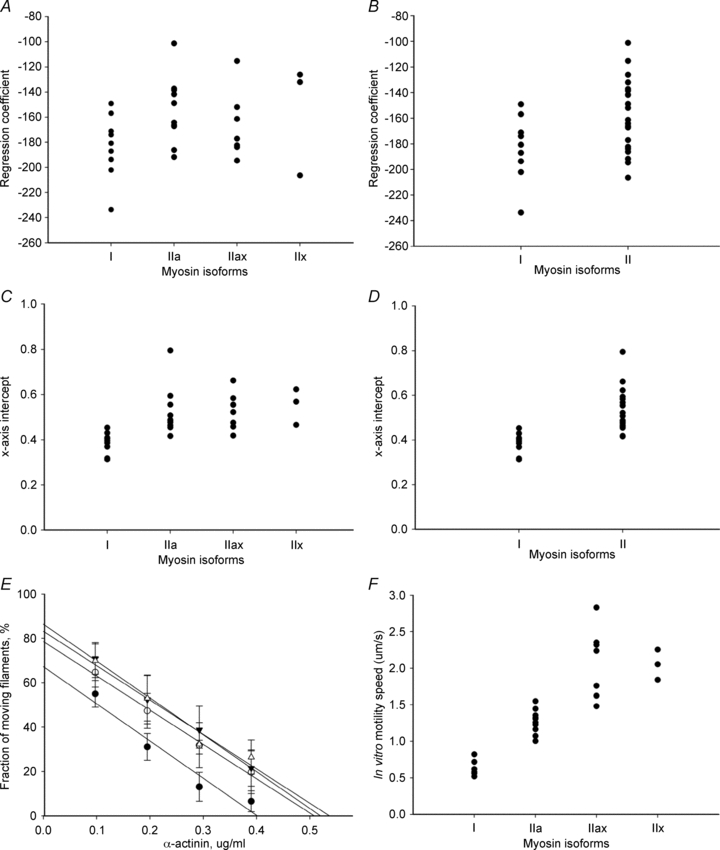

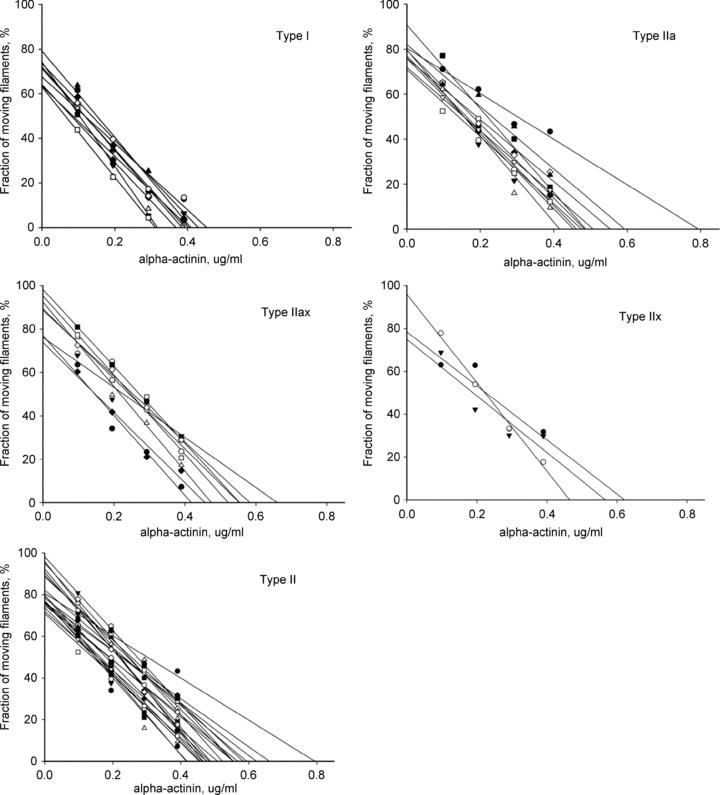

Two force indices were used. First, the slope (regression coefficient, force indexslope) of the negative linear relationship between the relative fraction of moving filaments, i.e. the percentage of moving filaments prior to addition of α-actinin in increasing concentrations and omitting the initial recording prior to addition of α-actinin since it may have a disproportional large impact on the regression line. Second, the x-axis intercept was also used as a force index (force indexintercept, Fig. 1). There were no outliers according to Grubbs’ test. Individual regression lines are presented in Fig. 2 to demonstrate the quality of the data.

Figure 1. Force index and motility speed of human myosin isoforms.

A–D, distribution of both force indexslope and force indexintercept in type I (n= 9), IIa (n= 10), IIax (n= 8) and IIx (n= 3) myosin isoforms (A and C) and with type I (n= 9) and pooled II (n= 22) myosin isoforms (B and D). E, negative linear regression between fraction of moving filaments (%) and α-actinin concentration (μg ml−1) of myosin isoforms type I (•, slope =−183 ± 25), IIa (○, slope =−154 ± 27), IIax (▾, slope =−166 ± 25) and IIx (▵, slope =−155 ± 45). Actin filament motility speed propelled by type I (n= 9), IIa (n= 10), IIax (n= 8) and IIx (n= 3) (F).

Figure 2. The individulised linear regression between fraction of moving filaments (%) and α-actinin concentration (μg ml−1) of each myosin isoforms.

The force indexslope for type I, IIa, IIax and IIx myosin preparations were −183 ± 25, −154 ± 27, −166 ± 25 and −155 ± 45, respectively (Fig. 1A and E). The force indexslope did not differ between the different type II myosin isoforms (P > 0.05) and the average force indexslope among pooled type II isoforms was −158 ± 27. The force indexslope for type I myosin preparations was lower (P < 0.05) than the pooled type II myosin force indexslope (Fig. 1B).

The force indexintercept for the type I, IIa, IIax and IIx myosin preparations were 0.39 ± 0.05, 0.52 ± 0.11, 0.53 ± 0.08 and 0.55 ± 0.08 respectively (Fig. 1C). The force indexintercept did not differ between the different type II myosin isoforms (P > 0.05) and the average force indexintercept among pooled type II isoforms was 0.53 ± 0.09. The force indexintercept for type I myosin preparations was lower (P < 0.01) than the pooled type II myosin force indexslope (Fig. 1D).

Both force indexslope and force indexintercept were measured in two adjacent regions in the central part of the flow cell. Identical results regarding force differences between MyHC isoforms were obtained in both regions and there was no significant difference between the two regions for either force indexslope or force indexintercept.

Motility speed and myosin isoforms

In accordance with our previous observations (Hook et al. 1999; Hook & Larsson, 2000), motility speed differed significantly (P < 0.001) between myosin isoforms. Further, there was no overlap in motility speed between the type I (0.62 ± 0.09 μm s−1), IIa (1.27 ± 0.16 μm s−1) and IIx (2.05 ± 0.21 μm s−1) myosin isoforms. The motility speed in myosin preparations from fibres co-expressing the type IIa and IIx myosin isoforms (IIax, 2.03 ± 0.47 μm s−1) overlapped the speeds recorded in type IIa and IIx myosin preparations (Fig. 1F). In contrast to motility speed, there was a significant overlap in force-generating capacity (force indexintercept and force indexslope) among all myosin isoforms (Fig. 1A–D).

Force index and motility speed

A significant correlation between force and motility speed was observed only in type IIa myosin preparations, but this result is probably spurious because this correlation was restricted to the force indexslope and not confirmed for force indexintercept (Table 1). A strong correlation between force indexintercept and force indexslope was observed for all myosin isoform preparation, but did not reach significance for the IIx myosin isoform because of too few fibres expressed only the IIx MyHC isoform (Table 2). The increase in temperature from 25 to 30°C significantly increased motility speed (P < 0.01) from 1.32 ± 0.71 to 2.01 ± 0.86 μm s−1 in six different fibre preparations (data have been pooled irrespective of MyHC isoform expression due to the small sample size). In contrast, the force index was unaffected by increased motility speed and temperature.

Table 1.

Linear correlations between force index (force indexslope and force indexintercept) and motility speed of different myosin isoforms

| I | IIa | IIax | IIx | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient (force indexslopevs. speed) | 0.004 | 0.634 | −0.188 | −0.891 |

| P value | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.30 |

| Correlation coefficient (force indexinterceptvs. speed) | −0.253 | 0.553 | −0.215 | −0.982 |

| P value | 0.51 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.12 |

Table 2.

Correlation analysis between force indexintercept and force indexslope within the different myosin isoforms

| I | IIa | IIax | IIx | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | 0.812 | 0.881 | 0.785 | 0.961 |

| P value | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

Discussion

A modified single fibre myosin in vitro motility assay has been introduced in this study to measure the force-generating capacity of specific myosin isoforms extracted from human muscle fibres. An actin-binding internal load (α-actinin) was added to the motility assay at increasing concentrations, reducing the number of moving actin filaments in an area with constant myosin concentration. Both the slope and x-axis intercept of the negative linear relationship between the fraction of moving filaments and α-actinin concentration was used as a force index. The force-generating capacity of the β/slow (type I) myosin isoform extracted from short single human muscle fibre segments was significantly weaker than the fast myosin isoform (type II), but no significant differences were observed among the fast myosin isoforms or combination of isoforms (type IIa, IIax and IIx).

Methodological considerations

The microneedle and the optical trap have been developed to evaluate the force-generating capacity of molecular motors such as myosin (Yanagida et al. 1993; Finer et al. 1994). These advanced techniques require highly specialized equipment with fine control of load and movement, and only few myosin molecules are allowed to interact with a single thin filament (Bing et al. 2000; Holohan & Marston, 2005). These advanced methods have given important and detailed information on the force produced by a single myosin molecule and the length of the power stroke, but have to our knowledge not been used to evaluate the function of human muscle myosin or specific myosin isoforms. A simple and high-throughput method to measure force-generating capacity of myosin was developed by Bing et al. (2000) and used by other groups (VanBuren et al. 2002; Foster et al. 2003; Malmqvist et al. 2004; Hunlich et al. 2005; Lecarpentier et al. 2008; Saber et al. 2008; Snook et al. 2008; Greenberg et al. 2009). The principle is that an internal load (actin-binding protein) is added to the motility assay to retard thin filament movement and the concentration of internal load needed to reduce or stop motility is proportional to the force generated by the motor protein (Bing et al. 2000).

The single fibre myosin in vitro motility assay, where myosin–actin interactions are studied after extraction of the motor protein from 1–2 mm long muscle fibre segments, was used in this study. This method has the advantage that the function of specific myosin isoforms can be studied from any mammalian species, including humans. In accordance with our original hypothesis, this motility assay proved suitable for measurements of the force-generating capacity, in addition to motility speed, by specific human myosin isoforms. The variability in motility speed of actin filaments is significantly reduced by analysing only actin filaments with organized bi-directional motility; bi-directional motility is also one of the criteria for acceptance in the single muscle fibre in vitro motility assay (Hook et al. 1999; Hook & Larsson, 2000). The exact mechanism underlying the directionally organized motility remains unknown, but it is assumed that myosins extracted in high salt solution form myosin filaments in low salt solution. Subsequently these filaments are organized according to the flow in the experimental chamber, attached to the surface and form organized myosin filaments in the central region with a high myosin density (Hook et al. 1999; Hook & Larsson, 2000). The very short actin filament length in this motility assay, probably caused by disruption of the actin filaments in the central high myosin density region, may contribute to the higher speed and lower variability in actin filament speed.

The frictional load exerted by α-actinin was originally considered to be elastic (Bing et al. 2000), but it has recently been suggested to be viscoelastic (Greenberg & Moore, 2010). If so, the same concentration of α-actinin could generate different forces in preparations with different velocities; however, for a specific MyHC isoform preparation, force index did not change over a large range of motility speeds and although increasing temperature from 25 to 30°C in the same fibre preparation, increased motility speed by 50%, there was no corresponding effect on the force index. This argues against viscoelasticity having a substantial confounding effect on the force recordings in the single muscle fibre in vitro motility assay.

Effects of α-actinin concentration on speed and fraction of moving filaments

The fraction and velocity of moving actin filaments were studied at increasing α-actinin concentrations. In this study, using the single fibre myosin in vitro motility assay, the fraction of moving filaments decreased with increasing α-actinin concentration but velocity did not change. In conventional in vitro motility assays both fraction and speed of moving filaments have been used to evaluate the force production. In the pioneering work of Bing et al. (2000), a consistent linear relationship to α-actinin concentration, was observed for the fraction of moving filaments, but not for actin filament velocity. Similar results were recently obtained by Lecarpentier et al. (2008). In other in vitro motility assays, thin filament velocity has proven to be a sensitive indicator of the inhibitory effect of α-actinin (VanBuren et al. 2002).

The different inhibitory effects of α-actinin on actin filament speed and fraction of moving filaments could be due to: (i) the influence of myosin concentration on motility speed, or (ii) the binding process of α-actinin to actin. First, there is a sigmoid relationship between thin filament velocity and myosin concentration, i.e. at very low myosin concentration the velocity will increase with increasing myosin concentration and remain constant above a certain critical level independent of myosin concentration (VanBuren et al. 2002). In the conventional in vitro motility assay, myosin concentration may be uneven in the experimental chamber and very low in some areas. This may accordingly have an effect on motility speed at different α-actinin concentrations. In the single fibre myosin in vitro motility assay, motility is only measured in the central myosin high-density region extracted from the fibre segment, with bi-directional motility in the 2 μl flow cell (Hook & Larsson, 2000). Second, cooperative molecular interactions have been demonstrated in many biological processes (Hill et al. 1992; Duke, 1999; Seyfried et al. 2006) and there may be cooperative interaction between actin and α-actinin, i.e. actin filament motility keeps constant speed and might be completely inhibited when α-actinin concentration reaches some critical level.

Myosin concentration and force index

Force production is proportional to the concentration of myosin molecules interacting with actin (He et al. 2000); thus, the fraction of moving actin filaments is dependent on the concentration of both myosin and α-actinin. The α-actinin concentration is known but it is not necessary or practical to quantify precisely the myosin concentration in the central high-density myosin region of the flow cell. In addition, in a specific region, the total myosin content also includes non-functional myosin motors; therefore, because, the concentration of force-generating myosin molecules remains constant in a region throughout the experiment, we measured the number of moving filaments in a specific region in the flow cell at the different α-actinin concentrations and normalized to the number of moving filaments without α-actinin.

Force-generating capacity of human myosin isoforms

This study shows that slow (type I) myosin is weaker than fast (type II) myosin in human skeletal muscle, while the force index is similar among the different fast myosin isoforms that are expressed in adult human limb muscles. This finding has important physiological and clinical implications for motor performance during posture and locomotion, as well as for muscle adaptations to physical exercise and neuromuscular disorders. The exact mechanisms underlying the myosin isoform specific differences in force production cannot be determined from the present experiments but are suggested to be secondary to two things. First, quantitative difference in the working stroke between fast and slow myosin. In slow myosin, the working stroke generates movement in two distinct steps. In fast myosin, on the other hand, the second step is undetectable or the two steps are much faster than in slow myosin (Veigel et al. 1999; Ruegg et al. 2002; Capitanio et al. 2006). Second, different conformational changes of fast and slow myosin heads upon ADP binding (Iwamoto et al. 2007).

In accordance with our previous observations, there was no overlap in in vitro motility speed between different myosin isoforms (Hook et al. 1999; Hook et al. 2001; Ramamurthy et al. 2001; Ramamurthy et al. 2003). This is in sharp contrast to force measurements where a significant overlap was observed among all isoforms, indicating that the variability in myosin isoform specific differences in force generation capacity and contractile speed are regulated by different mechanisms. That is, force is generated during the ‘power stroke’ and the rapid release of phosphate after attachment of the myosin head to the actin filament (Duke, 1999; Takagi et al. 2004), while sliding velocity is primarily regulated by myosin detachment rate (Siemankowski et al. 1985; Nyitrai et al. 2006; Hooft et al. 2007).

Conclusions

The modified single fibre in vitro motility assay offers a unique possibility to measure the force-generating capacity of specific myosin isoforms. Using it, we found that the slow human myosin isoform (type I) is weaker than fast (type II) myosin isoforms, but that the fast fibre isoforms (type IIa, IIax and IIx) were similar to one another. The method that we have described offers a platform for future clinical studies of myosin function in the growing disease entity called ‘myosinopathies’ (Shrager et al. 2000) as well as a way to evaluate different post-translational myosin modifications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr B. Dworkin for English editing and comments on the manuscript, Ms Yvette Hedström and Ann-Marie Gustafsson for the gel electrophoresis analyses, Ms Mengque Liu for the guidance in statistical methods, Mr Zhitao He and Guillaume Renaud for the assistance in image analysis. We thank the human subjects for providing muscle tissue, making this work possible. This study was supported by grants from the Uppsala University (Postdoctoral Fellowship, 2009) and the Swedish National Centre for Research in Sports (CIF) (143/10) to M.L., the Swedish Medical Research Council (08651) and the European Commission (MyoAge, EC Fp7 CT-223756, COST CM1001) to L.L.

Author contributions

All experiments were performed at the Department of Neuroscience, Clinical Neurophysiology Section, Uppsala University. The contributions of the authors were as follows: conception and design of the experiments: M.L. and L.L.; collection, analysis and interpretation of data: M.L.; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: M.L. and L.L.; final approval of the version to be published: L.L.

References

- Andruchov O, Andruchova O, Wang Y, Galler S. Kinetic properties of myosin heavy chain isoforms in mouse skeletal muscle: comparison with rat, rabbit, and human and correlation with amino acid sequence. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1725–1732. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00255.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barany M. ATPase activity of myosin correlated with speed of muscle shortening. J Gen Physiol. 1967;50(Suppl):197–218. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.6.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing W, Knott A, Marston SB. A simple method for measuring the relative force exerted by myosin on actin filaments in the in vitro motility assay: evidence that tropomyosin and troponin increase force in single thin filaments. Biochem J. 2000;350:693–699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottinelli R. Functional heterogeneity of mammalian single muscle fibres: do myosin isoforms tell the whole story? Pflugers Arch. 2001;443:6–17. doi: 10.1007/s004240100700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottinelli R, Canepari M, Reggiani C, Stienen GJ. Myofibrillar ATPase activity during isometric contraction and isomyosin composition in rat single skinned muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1994;481:663–675. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE. Motor units: Anatomy, physiology and functional organization. In: Brooks VB, editor. Handbook of Physiology, section 1, The Nervous System, vol. 2, Motor Control. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1981. pp. 345–422. [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio M, Canepari M, Cacciafesta P, Lombardi V, Cicchi R, Maffei M, Pavone FS, Bottinelli R. Two independent mechanical events in the interaction cycle of skeletal muscle myosin with actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:87–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506830102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke TA. Molecular model of muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2770–2775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum RP, Kennedy TT. Physiological and histochemical characteristics of motor units in cat tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles. J Neurophysiol. 1980;43:1615–1630. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer JT, Simmons RM, Spudich JA. Single myosin molecule mechanics: piconewton forces and nanometre steps. Nature. 1994;368:113–119. doi: 10.1038/368113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DB, Noguchi T, VanBuren P, Murphy AM, Van Eyk JE. C-terminal truncation of cardiac troponin I causes divergent effects on ATPase and force: implications for the pathophysiology of myocardial stunning. Circ Res. 2003;93:917–924. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000099889.35340.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaser ML, Moss RL, Reiser PJ. Variations in contractile properties of rabbit single muscle fibres in relation to troponin T isoforms and myosin light chains. J Physiol. 1988;406:85–98. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MJ, Moore JR. The molecular basis of frictional loads in the in vitro motility assay with applications to the study of the loaded mechanochemistry of molecular motors. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:273–285. doi: 10.1002/cm.20441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MJ, Watt JD, Jones M, Kazmierczak K, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Regulatory light chain mutations associated with cardiomyopathy affect myosin mechanics and kinetics. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ZH, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA, Ferenczi MA, Reggiani C. ATP consumption and efficiency of human single muscle fibers with different myosin isoform composition. Biophys J. 2000;79:945–961. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76349-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LE, Mehegan JP, Butters CA, Tobacman LS. Analysis of troponin-tropomyosin binding to actin. Troponin does not promote interactions between tropomyosin molecules. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16106–16113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holohan SJ, Marston SB. Force-velocity relationship of single actin filament interacting with immobilised myosin measured by electromagnetic technique. IEE Proc Nanobiotechnol. 2005;152:113–120. doi: 10.1049/ip-nbt:20045003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooft AM, Maki EJ, Cox KK, Baker JE. An accelerated state of myosin-based actin motility. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3513–3520. doi: 10.1021/bi0614840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook P, Larsson L. Actomyosin interactions in a novel single muscle fiber in vitro motility assay. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2000;21:357–365. doi: 10.1023/a:1005614212575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook P, Li X, Sleep J, Hughes S, Larsson L. In vitro motility speed of slow myosin extracted from single soleus fibres from young and old rats. J Physiol. 1999;520:463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook P, Sriramoju V, Larsson L. Effects of aging on actin sliding speed on myosin from single skeletal muscle cells of mice, rats, and humans. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C782–788. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunlich M, Begin KJ, Gorga JA, Fishbaugher DE, LeWinter MM, VanBuren P. Protein kinase A mediated modulation of acto-myosin kinetics. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto H, Oiwa K, Kovacs M, Sellers JR, Suzuki T, Wakayama J, Tamura T, Yagi N, Fujisawa T. Diversity of structural behavior in vertebrate conventional myosins complexed with actin. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:249–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda K, Hashizume K. Factors causing difference in force output among motor units in the rat medial gastrocnemius muscle. J Physiol. 1992;448:677–695. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kean CJ, Lewis DM, McGarrick JD. Dynamic properties of denervated fast and slow twitch muscle of the cat. J Physiol. 1974;237:103–113. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L, Moss RL. Maximum velocity of shortening in relation to myosin isoform composition in single fibres from human skeletal muscles. J Physiol. 1993;472:595–614. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecarpentier Y, Vignier N, Oliviero P, Guellich A, Carrier L, Coirault C. Cardiac Myosin-binding protein C modulates the tuning of the molecular motor in the heart. Biophys J. 2008;95:720–728. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Larsson L. Maximum shortening velocity and myosin isoforms in single muscle fibers from young and old rats. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1996;270:C352–360. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.1.C352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linari M, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA, Reconditi M, Reggiani C, Lombardi V. The mechanism of the force response to stretch in human skinned muscle fibres with different myosin isoforms. J Physiol. 2004;554:335–352. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.051748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist UP, Aronshtam A, Lowey S. Cardiac myosin isoforms from different species have unique enzymatic and mechanical properties. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15058–15065. doi: 10.1021/bi0495329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyitrai M, Rossi R, Adamek N, Pellegrino MA, Bottinelli R, Geeves MA. What limits the velocity of fast-skeletal muscle contraction in mammals? J Mol Biol. 2006;355:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochala J, Li M, Ohlsson M, Oldfors A, Larsson L. Defective regulation of contractile function in muscle fibres carrying an E41K β-tropomyosin mutation. J Physiol. 2008;586:2993–3004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee JD, Spudich JA. Purification of muscle actin. Methods Enzymol. 1982;85:164–181. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafuse VF, Pattullo MC, Gordon T. Innervation ratio and motor unit force in large muscles: a study of chronically stimulated cat medial gastrocnemius. J Physiol. 1997;499:809–823. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthy B, Hook P, Jones AD, Larsson L. Changes in myosin structure and function in response to glycation. FASEB J. 2001;15:2415–2422. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0183com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthy B, Jones AD, Larsson L. Glutathione reverses early effects of glycation on myosin function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C419–424. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00502.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiani C, Potma EJ, Bottinelli R, Canepari M, Pellegrino MA, Stienen GJ. Chemo-mechanical energy transduction in relation to myosin isoform composition in skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol. 1997;502:449–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.449bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegg C, Veigel C, Molloy JE, Schmitz S, Sparrow JC, Fink RH. Molecular motors: force and movement generated by single myosin II molecules. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:213–218. doi: 10.1152/nips.01389.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saber W, Begin KJ, Warshaw DM, VanBuren P. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C modulates actomyosin binding and kinetics in the in vitro motility assay. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock TG. Summation of motor unit force in passive and active muscle. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005;33:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200504000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter JM, Fitts RH. Shortening velocity and ATPase activity of rat skeletal muscle fibers: effects of endurance exercise training. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1994;266:C1699–1673. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebohm B, Matinmehr F, Kohler J, Francino A, Navarro-Lopez F, Perrot A, Ozcelik C, McKenna WJ, Brenner B, Kraft T. Cardiomyopathy mutations reveal variable region of myosin converter as major element of cross-bridge compliance. Biophys J. 2009;97:806–824. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfried NT, Day AJ, Almond A. Experimental evidence for all-or-none cooperative interactions between the G1-domain of versican and multivalent hyaluronan oligosaccharides. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrager JB, Desjardins PR, Burkman JM, Konig SK, Stewart SK, Su L, Shah MC, Bricklin E, Tewari M, Hoffman R, Rickels MR, Jullian EH, Rubinstein NA, Stedman HH. Human skeletal myosin heavy chain genes are tightly linked in the order embryonic-IIa-IId/x-ILb-perinatal-extraocular. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2000;21:345–355. doi: 10.1023/a:1005635030494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemankowski RF, Wiseman MO, White HD. ADP dissociation from actomyosin subfragment 1 is sufficiently slow to limit the unloaded shortening velocity in vertebrate muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:658–662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snook JH, Li J, Helmke BP, Guilford WH. Peroxynitrite inhibits myofibrillar protein function in an in vitro assay of motility. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi Y, Shuman H, Goldman YE. Coupling between phosphate release and force generation in muscle actomyosin. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1913–1920. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBuren P, Alix SL, Gorga JA, Begin KJ, LeWinter MM, Alpert NR. Cardiac troponin T isoforms demonstrate similar effects on mechanical performance in a regulated contractile system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1665–1671. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00938.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veigel C, Coluccio LM, Jontes JD, Sparrow JC, Milligan RA, Molloy JE. The motor protein myosin-I produces its working stroke in two steps. Nature. 1999;398:530–533. doi: 10.1038/19104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida T, Ishijima A, Saito K, Harada Y. Coupling between ATPase and force-generating attachment-detachment cycles of actomyosin in vitro. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;332:339–347. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2872-2_33. discussion 347–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]