Abstract

Suboptimal conditions in utero can have long-lasting effects including increased risk of cardiovascular disease in adult life. Such programming effects may be induced by chronic systemic hypoxia in utero (CHU). We have investigated how CHU affects cardiovascular responses evoked by acute systemic hypoxia in adult male offspring, recognising that adenosine contributes to hypoxia-induced muscle vasodilatation and bradycardia by acting on A1 receptors in normal (N) rats. In the present study, dams were housed in a hypoxic chamber at 12% O2 for the second half of gestation; offspring were born and reared in air until 9–10 weeks of age. Under anaesthesia, acute systemic hypoxia (breathing 8% O2 for 5 min) evoked similar biphasic tachycardia/bradycardia, fall in arterial pressure and increase in femoral vascular conductance (FVC) in N and CHU rats (+2.0 vs.+2.7 conductance units respectively). However, in CHU rats, neither the non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist 8-sulphophenyltheopylline (8-SPT), nor the A1 receptor antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) affected the increase in FVC, but DPCPX attenuated the hypoxia-induced bradycardia. Further, in N and CHU rats, 5 min infusion of adenosine induced similar increases in FVC; in CHU rats, DPCPX reduced the adenosine-induced increase in FVC (by =50%) and accentuated the concomitant tachycardia. These results suggest that CHU rats have functional A1 receptors in heart and vasculature, but the release and/or vasodilator influence of adenosine on the endothelium in acute hypoxia is attenuated and replaced by other dilator factors. Such changes from normal endothelial function may have implications for general cardiovascular regulation.

Introduction

During development, the fetus may be exposed to a variety of environmental insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or stress, which can have a profound effect on the growth of the fetus in utero and result in intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR; see Hoet & Hanson, 1999). The effects of such insults in utero are long lasting and persist into adulthood even if the stimuli are apparently removed at birth (see Louey & Thornburg, 2005). This phenomenon of developmental or fetal programming was originally described by Barker (1995, 1998). Current evidence indicates a link between developmental programming and altered cardiovascular function that leads to disease states such as diabetes and hypertension (e.g. Hoet & Hanson, 1999).

Much of this evidence has been gathered from dietary manipulation during pregnancy (see Hoet & Hanson, 1999; Bertram & Hanson, 2001). For example, the progeny of rat dams which were fed a protein-restricted diet during gestation developed hypertension at maturity (Langley-Evans, 1997a,b; Ozaki, 2001). Further, in protein-restricted pregnancies, the development of the fetal pancreas was impaired, ultimately contributing to the development of diabetes (see Hoet & Hanson, 1999).

By contrast, there is little information on the effects of chronic hypoxia in utero (CHU), even though fetal hypoxia can accompany placental insufficiency, cord compression and anaemia (see review of Morrison, 2008). Of the few studies, the progeny of rat dams that were exposed to different levels of hypoxia showed overall growth retardation that was graded with the level of hypoxia, but spared the brain (de Grauw et al. 1986), similar to the effects of under-nutrition in pregnancy (see Burdge et al. 2002). However, when rat dams were exposed to 12% O2 in the last part of pregnancy (days 15–22), the femoral arteries of the CHU neonates (3–12 h post partum) showed augmented responses to phenylephrine and unchanged responses to endothelin-1, while carotid arteries showed augmented responses to both vasoconstrictors relative over those of control neonates and nutrient restricted (NR) neonates (Williams et al. 2005a). At 4 months of age, the mesenteric resistance arteries of CHU rats showed decreased sensitivity to the endothelium-dependent dilator methacholine relative to NR and control rats, but was nitric oxide (NO) dependent, in all groups. Moreover, by 7 months, in CHU rats only, methacholine-induced relaxation in mesenteric arteries was not NO dependent but was increased by superoxide dismutase (SOD) suggesting NO availability was attenuated (Williams et al. 2005b). These results suggest that the vascular effects induced by NR and CHU may be different in arterial vessels that supply different vascular beds, and that CHU may accentuate vasoconstrictor responsiveness and/or lead to endothelial dysfunction. In addition, CHU rats that were exposed to 10% O2 from day 5 to day 20 of pregnancy showed alterations in the postnatal development of respiratory sensitivity to acute systemic hypoxia and changes in central neural catecholaminergic pathways that regulate sympathetic outflow. Further, at 12 weeks of age, they showed increased pressor responses to acute stress relative to control rats (Peyronnet et al. 2002, 2007).

Considered together, these results are particularly interesting because in adult rats, and indeed in humans, the peripheral vascular response induced by acute systemic hypoxia is heavily dominated by endothelium-dependent dilatation, which predominates over the sympathetic vasoconstrictor influence of peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation (Marshall, 1994). Thus, in control, normoxic (N) rats, acute systemic hypoxia induces vasodilatation in skeletal muscle that is largely mediated by adenosine acting on A1 but not A2A receptors (Bryan & Marshall, 1999), and is NO dependent (Skinner & Marshall, 1996). Indeed, the hypoxia-induced muscle vasodilatation requires a tonic influence of NO for adenosine to be released from the endothelium and is largely NO mediated, involving stimulation of endothelial A1 receptors to release NO (Ray et al. 2002; Edmunds et al. 2003; Ray & Marshall, 2005). However, when rats were made chronically hypoxic from birth, they showed increased baseline vascular conductance in hindlimb muscles, and substantial muscle vasodilatation to acute hypoxia, but neither was affected by adenosine receptor blockade, indicating that chronic hypoxia from birth attenuates the vasodilator influence of adenosine (Thomas & Marshall, 1995). This raises an obvious question as to whether CHU produces similar effects.

Against this background, the aims of the present study were to establish how CHU affects the cardiovascular responses evoked by acute systemic hypoxia in adult life and in particular, to establish whether or not the muscle vasodilator influence of adenosine on A1 receptors is altered.

The role of the A1 receptors was of special interest because even though A1 receptors, are not critical for normal embryonic development, they apparently play an essential role in protecting the embryo against hypoxia: when A1 receptor-knockout mice were exposed to hypoxia during pregnancy, embryonic mortality was substantially increased (Wendler et al. 2007).

Methods

Experiments were performed on male Wistar rats that were either control, normoxic (N) rats, or were the progeny of dams (n= 4) that were exposed to hypoxia during pregnancy and were therefore subjected to chronic hypoxia in utero (CHU rats): the N rats and rat dams were supplied by Charles River Ltd (Hythe, UK). The dams were mated in house: the presence of a vaginal plug was used to confirm mating and was designated day 0 of pregnancy. Each dam was kept in a standard cage and breathed air from day 0 to day 10. On day 10, the cage was placed in a normobaric chamber at 12% O2 until day 20 and then moved back to room air. The offspring were born into air and grew up breathing air. Details of the hypoxic chamber have been published previously (see Thomas & Marshall, 1995). In brief, O2 levels were maintained in the range 11.75–12.25% and the build-up of CO2, humidity and ammonia was prevented by appropriate scrubbing procedures (soda lime, silica gel and molecular sieve, respectively). The hypoxic chamber was opened to air twice weekly for 15–20 min so that the cages could be cleaned and the animals weighed.

Following weaning and sexing, the CHU rats were housed in standard conditions with free access to food and water until the day of the acute experiment at ∼9–10 weeks old: they were age-matched to the N rats. Each experimental group comprised offspring from more than one litter. All experiments were performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, and the experiments comply with the guidance of The Journal of Physiology (Drummond, 2009).

On the day of the acute experiment, the CHU or N rat was prepared for recording cardiovascular variables, using anaesthetic and surgical procedures that have been described in detail before (Coney & Marshall, 2003). In brief, rats were initially anaesthetized with halothane (3.5% in O2) to allow cannulation of a jugular vein. Halothane anaesthesia was then withdrawn and in Groups 2, 3 and 4, the steroid anaesthetic Saffan (Schering-Plough Animal Health, Welwyn Garden City, UK) was continuously infused at 7–12 mg kg−1 h−1i.v. In Group 1, exactly the same regime was followed with Alfaxan, which is the commercial replacement of Saffan (which is no longer available). The depth of anaesthesia was judged by the absence of a withdrawal response to a paw pinch and during the experiment proper (see below), by the stability of the arterial blood pressure (ABP) and respiratory movements. At the end of the experiments all the animals were humanely killed by anaesthetic overdose.

The trachea was cannulated with a T-shaped cannula to maintain a patent airway. The side-arm of the cannula was connected to a system of rotameters in a gas proportioner frame (CP Instruments Co. Ltd London, UK) which allowed the inspiratory gases to be varied from air (breathing 21% O2) to acute systemic hypoxia (breathing 8% O2). Both brachial arteries were cannulated to allow monitoring of ABP and to allow 150μl samples to be taken anaerobically at intervals (see below) for analysis on a blood gas machine (IL1640; Instrumentation Laboratories, Warrington, UK). Femoral blood flow was recorded from the right femoral artery by means of a perivascular flowprobe (0.7V; Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY, USA) that was connected to a flowmeter (T106; Transonic Systems). Data (femoral blood flow (FBF) and ABP) were acquired digitally into Chart (ADInstruments) via a Powerlab 4/25 (ADInstruments Chalgrove, UK) at a sampling rate of 100Hz. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were derived online from the ABP signal whilst femoral vascular conductance (FVC) was calculated online by the division of FBF by ABP. Following surgery the animal was allowed a stabilisation period of at least 30 min before the protocol was started.

Protocols

Protocol 1. Responses evoked by acute hypoxia and effects of adenosine receptor blockade

These experiments were performed on seven N rats (344 ± 5 g; Group 1) and nine CHU rats (290 ± 9 g; Group 2). After the stabilisation period and a baseline period of at least 5 min, the inspirate was switched from 21 to 8% O2 for a period of 5 min and then back again. Arterial blood gas samples were taken just prior to and in the fifth minute of the hypoxic period. After the recovery of a steady baseline in normoxia, in the N rats and in six of the CHU rats, the adenosine receptor antagonist 8-sulphophenyltheophylline (8-SPT) was given into the brachial artery at a dose of 20 mg kg−1. 8-SPT is non-selective between adenosine receptor subtypes and does not cross the blood–brain barrier (see Evoniuk et al. 1987). The dose used in the present study was shown previously to effectively block the cardiac and vascular actions of adenosine on A1 receptors during acute hypoxia (Thomas et al. 1994). After a 15 min equilibration period, the responses evoked by a further 5 min period of hypoxia were re-tested as just described.

Protocol 2. Effects of A1 receptor blockade on adenosine- and hypoxia-induced vasodilatation

These experiments were performed on seven N rats (340 ± 4 g; Group 3) and eight male CHU rats (321 ± 9 g; Group 4). In addition to the surgical preparation described above, the caudal ventral tail artery (CVA) was cannulated to allow an infusion of adenosine. Following the initial stabilisation period, adenosine was infused into the CVA at a rate of 0.5 mg kg−1 h−1 for 5 min whilst the rat continued to breathe 21% O2. This dose of adenosine is the one we have previously used in N rats to produce a an increase in FVC that is approximately 50% of that evoked by breathing 8% O2 for 5 min, i.e. the component of the hypoxia-induced dilatation that can be attributed to adenosine in N rats (see Coney & Marshall, 2003).

In six of the CHU rats, the responses evoked by acute systemic hypoxia were also tested as described for Protocol 1, arterial blood samples being taken in normoxia and the fifth minute of hypoxia.

Following recovery of baselines, the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) was given to the CHU rats at 0.1 mg kg−1i.v., which reverses responses evoked by a selective A1 receptor agonist and attenuates muscle vasodilatation and bradycardia evoked by systemic hypoxia (see Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Coney & Marshall, 2003). After a 15 min equilibration period, the responses evoked by adenosine infusion and by systemic hypoxia, were re-tested.

Data analysis

All data are presented as means ±s.e.m. Analysis was performed essentially as described in Coney & Marshall (2007). Thus, the size of the muscle vasodilator response was calculated by subtracting the value of the integrated FVC recorded during the response to adenosine or hypoxia from a corresponding time period of baseline FVC recorded until immediately before the stimulus. The integrated dilator response is expressed in arbitrary conductance units (CU). The changes in the other recorded variables (ABP, HR and FBF) are expressed as the mean change over the time periods that were used to assess the dilator response. Comparison of baselines in normoxia between N and CHU groups was made by Student's unpaired t test. Comparison of the changes induced by hypoxia (or adenosine infusion) and any effect of the antagonist (8-SPT or DPCPX) on the evoked responses between N and CHU groups was made by two-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05.

Results

Comparison of baselines

The cardiovascular baseline values while breathing 21% O2 for Groups 1 and 3 (N rats) and Groups 2 and 4 (CHU rats) are shown in Table 1, while Table 2 shows arterial blood gases and pH during 21% O2 and 8% O2. During 21% O2, ABP, HR and integrated femoral vascular conductance (IntFVC) tended to be higher in CHU than N rats, but were not significantly different; FBF was significantly higher in CHU than N rats (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). CHU rats had similar  values, but significantly lower

values, but significantly lower  and arterial pH values than N rats. These differences apparently reflected the fact that the N rats of Group 1 had higher

and arterial pH values than N rats. These differences apparently reflected the fact that the N rats of Group 1 had higher  and lower pH values than in our previous studies (see Coney & Marshall, 2003) and Group 3 of the present study (see below).

and lower pH values than in our previous studies (see Coney & Marshall, 2003) and Group 3 of the present study (see below).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular baselines recorded during normoxia in the combined groups of N rats (Group 1 and 2) and CHU rats (Groups 3 and 4) in the absence of antagonists and in CHU rats after 8-SPT (Group 3) or DPCPX (Group 4)

| ABP (mmHg) | IntFVC (CU) | HR (beats min−1) | FBF (ml min−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (n= 14) | 129 ± 2 | 3.05 ± 0.28 | 414 ± 7 | 1.31 ± 0.12 |

| CHU (n= 17) | 131 ± 3 | 3.16 ± 0.24 | 434 ± 11 | 1.58 ± 0.09 * |

| CHU+8-SPT (n= 9) | 128 ± 3 | 3.85 ± 0.26 | 446 ± 15 | 1.60 ± 0.10 |

| CHU+DPCPX (n= 8) | 138 ± 3 | 2.47 ± 0.43 | 416 ± 10 | 1.51 ± 0.23 |

*P < 0.05: difference between values recorded in CHU and N rats.

Table 2.

Arterial blood gases and pH recorded in N and CHU rats during normoxia and in hypoxia (+H) in the absence and after the antagonists 8-SPT or DPCPX

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

pH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n= 8) | N | 86 ± 2 | 48.0 ± 1.3 | 7.383 ± 0.013 |

| N+H | 29 ± 3 | 30.9 ± 2.6 | 7.504 ± 0.038 | |

| N+8-SPT | 87 ± 5 | 44.7 ± 1.2 | 7.382 ± 0.009 | |

| N+H+8-SPT | 30 ± 1 | 27.7 ± 1.1 | 7.537 ± 0.015 | |

| Group 2 (n= 9) | CHU | 86 ± 2 | 34.9 ± 1.8*** | 7.465 ± 0.012*** |

| CHU+H | 31 ± 1 | 21.5 ± 1.5** | 7.572 ± 0.019 | |

| CHU+8-SPT | 86 ± 2 | 30.3 ± 1.0*** | 7.488 ± 0.013*** | |

| CHU+H+8-SPT | 32 ± 1 | 19.6 ± 1.3*** | 7.576 ± 0.019 | |

| Group 4 (n= 8) | CHU | 87 ± 2 | 37.6 ± 2.2 ** | 7.504 ± 0.014*** |

| CHU+H | 30 ± 1 | 21.4 ± 1.0 ** | 7.632 ± 0.10** | |

| CHU+DPCPX | 94 ± 3 | 32.5 ± 1.4*** | 7.543 ± 0.016*** | |

| CHU+H+DPCPX | 31 ± 1 | 19.6 ± 1.1*** | 7.655 ± 0.012*** |

**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: difference between values recorded in CHU and N rats in normoxia or in hypoxia. For clarity, statistical significance between values recorded in normoxia and hypoxia within groups are not shown: in each group, hypoxia induced a significant fall in  and

and  and an increase in pH in the absence and presence of 8-SPT or DPCPX.

and an increase in pH in the absence and presence of 8-SPT or DPCPX.

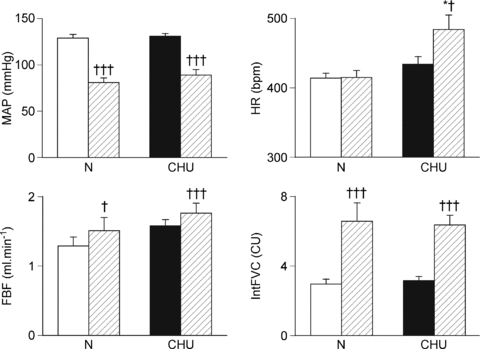

Figure 1. Effect of chronic hypoxia in utero (12% O2) on baseline cardiovascular variables and responses evoked by acute systemic hypoxia (8% O2).

Mean values ±s.e.m. of mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), femoral blood flow (FBF) and integrated femoral vascular conductance (IntFVC) are shown during normoxia (open and filled shading in N and CHU rats respectively) and for the 5 min period of hypoxia (hashed shading). †P < 0.05, †††P < 0.001: difference between normoxia and hypoxia in N or CHU rats; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001: difference between N and CHU in normoxia or hypoxia.

Protocol 1. Responses evoked by acute hypoxia and effects of adenosine receptor blockade

As expected, acute hypoxia induced a fall in  in N rats and the concomitant hyperventilation resulted in a fall in

in N rats and the concomitant hyperventilation resulted in a fall in  and increase in arterial pH. In CHU rats, hypoxia induced qualitatively similar changes in blood gases such that the levels of

and increase in arterial pH. In CHU rats, hypoxia induced qualitatively similar changes in blood gases such that the levels of  reached during hypoxia were not different between CHU and N rats (Table 2), and the levels of

reached during hypoxia were not different between CHU and N rats (Table 2), and the levels of  and pH remained higher in CHU than N as in normoxia (Table 2).

and pH remained higher in CHU than N as in normoxia (Table 2).

The pattern of cardiovascular response evoked by acute hypoxia in N rats (Group 1) was consistent with our previous findings, comprising a fall in ABP of ∼60 mmHg and an increase in FVC indicating hindlimb vasodilatation. There was also an initial tachycardia that waned during the hypoxic period, such that there was no significant change in HR over the 5 min period. Since the time course of these changes was entirely consistent with our previous findings (see Thomas et al. 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999), we have not illustrated them, but have shown the mean and integrated data over the 5 min period of hypoxia for direct comparison with the results obtained in CHU rats (see Fig. 1). In CHU rats (Group 2), hypoxia also induced a fall in ABP and a tachycardia that generally waned in individual rats (peaking at 511 ± 21 bpm at 2 min and waning to 501 ± 19 bpm at 5 min), i.e. a comparable response to that seen in N rats (see Figs 1 and 2). In CHU rats, the mean HR change amounted to a significant increase over the 5 min period of acute hypoxia. Because the fall in ABP tended to be smaller in the CHU than the N rats (40 vs. 50 mmHg; Fig. 1, P= 0.13), the level of ABP reached during 8% O2 was significantly higher in CHU than in N (see Fig. 1). CHU rats showed a similar increase in FVC to N rats (Fig. 2), indicating a comparable vasodilatation in hindlimb muscle (Fig. 1).

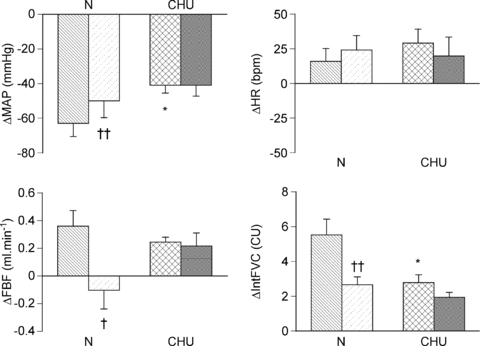

Figure 2. Effect of the adenosine receptor antagonist 8-SPT on cardiovascular responses evoked by acute systemic hypoxia in N and CHU rats.

Columns show mean change ±s.e.m. from baseline in mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), femoral blood flow (FBF) and integrated femoral vascular conductance (IntFVC) before (N: hatched, CHU: crosshatch) and after 8-SPT (N: hatched, CHU: stippled). †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01: difference between before and after 8-SPT; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01: difference between response evoked in N and CHU. There were no significant differences between values recorded before and after 8-SPT in CHU rats.

Administration of 8-SPT had no significant effect on baseline cardiovascular variables, blood gases or pH in either N or CHU rats (see Tables 1 and 2), consistent with our previous data in N rats (Thomas et al. 1994). This indicates no tonic effect of adenosine on basal vascular tone, or any net effect on respiration when the rats were breathing 21% O2, in N or CHU rats. Considering Fig. 2, which shows the changes in each variable before and after 8-SPT, in our N rats, the fall in ABP and increase in FVC evoked by hypoxia were attenuated by 8-SPT in agreement with our previous findings in N rats (see Thomas et al. 1994). By contrast, 8-SPT had no effect on the hypoxia-induced fall in ABP and increase in FVC in these CHU rats (Fig. 2; P= 0.19).

Protocol 2. Effects of A1 receptor blockade on responses evoked by adenosine or systemic hypoxia

In Group 3 (N rats), whilst breathing 21% O2 ( = 85 ± 1 mmHg,

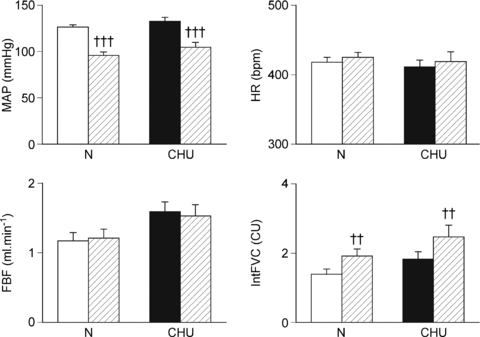

= 85 ± 1 mmHg,  = 27.7 ± 1.4 mmHg), infusion of adenosine induced a comparable pattern of response to that described before (e.g. Coney & Marshall, 2003) comprising a mean fall in ABP, no significant change in HR and an increase in IntFVC, allowing FBF to be maintained despite the fall in ABP (Fig. 3). In Group 4 (CHU rats) also, adenosine evoked a fall in ABP of similar magnitude, no change in HR, and a comparable increase in IntFVC to that seen in N rats, resulting in no significant change in FBF (Fig. 3).

= 27.7 ± 1.4 mmHg), infusion of adenosine induced a comparable pattern of response to that described before (e.g. Coney & Marshall, 2003) comprising a mean fall in ABP, no significant change in HR and an increase in IntFVC, allowing FBF to be maintained despite the fall in ABP (Fig. 3). In Group 4 (CHU rats) also, adenosine evoked a fall in ABP of similar magnitude, no change in HR, and a comparable increase in IntFVC to that seen in N rats, resulting in no significant change in FBF (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Cardiovascular responses evoked by infusion of adenosine in N and CHU rats.

Mean values ±s.e.m. of mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), femoral blood flow (FBF) and of integrated femoral vascular conductance (IntFVC) are shown before (open and filled shading in N and CHU rats, respectively) and during the 5 min of infusion (hatched shading). ††P < 0.01, †††P < <0.001: difference between values recorded before and during adenosine infusion.

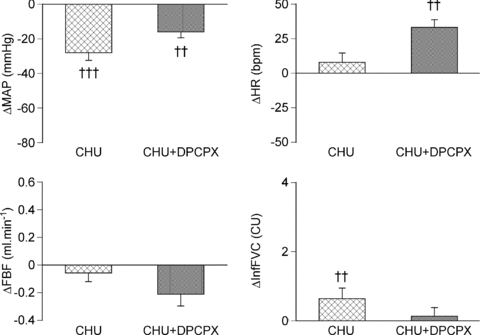

The changes in cardiovascular variables evoked by adenosine in CHU rats are shown in Fig. 4 for comparison with the changes evoked after DPCPX administration. Administration of DPCPX had no significant effect on any of the baselines in CHU rats (see Tables 1 and 2), although there was a tendency for  to increase (P= 0.0623). In our previous studies, administration of DPCPX in N rats has been shown to attenuate the fall in ABP and hindlimb vasodilatation induced by adenosine infusion by ∼50% and allowed a tachycardia to be manifest (Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Coney & Marshall, 2003; Ray & Marshall, 2005). Similarly, in the CHU rats, DPCPX attenuated the fall in ABP induced by adenosine, by ∼50%, and HR increased significantly from baseline. Moreover, the increase in IntFVC was reduced by ∼80% such that any remaining increase in IntFVC induced by adenosine infusion did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4).

to increase (P= 0.0623). In our previous studies, administration of DPCPX in N rats has been shown to attenuate the fall in ABP and hindlimb vasodilatation induced by adenosine infusion by ∼50% and allowed a tachycardia to be manifest (Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Coney & Marshall, 2003; Ray & Marshall, 2005). Similarly, in the CHU rats, DPCPX attenuated the fall in ABP induced by adenosine, by ∼50%, and HR increased significantly from baseline. Moreover, the increase in IntFVC was reduced by ∼80% such that any remaining increase in IntFVC induced by adenosine infusion did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Effect of the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist DPCPX on changes in cardiovascular variables evoked by infusion of adenosine in CHU rats.

Columns show mean change ±s.e.m. from baseline in mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), femoral blood flow (FBF) and integrated femoral vascular conductance (IntFVC) before (crosshatched) and after (stippled) DPCPX administration. ††P < 0.01, †††P < 0.001: difference between values recorded before and during adenosine infusion.

In the subgroup of CHU rats (n= 6) that were subjected to acute systemic hypoxia, this stimulus induced a fall in ABP and skeletal muscle dilatation as indicated by an increase in IntFVC (Fig. 5), as occurred in Group 2 CHU rats. In contrast to Group 2 CHU rats, the secondary bradycardia of the response was more pronounced such that the mean HR over the 5 min showed a significant bradycardia (Fig. 5).

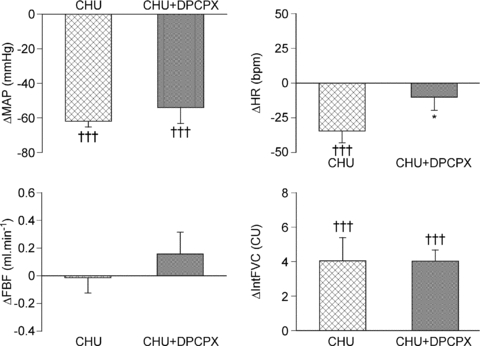

Figure 5. Effect of the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist DPCPX on changes in cardiovascular variables evoked by acute systemic hypoxia in CHU rats.

Columns show mean change ±s.e.m. from baseline in mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), femoral blood flow (FBF) and integrated femoral vascular conductance (IntFVC) before (crosshatched) and after (stippled) DPCPX adminstration. †††P < 0.001: difference between normoxia and hypoxia in N or CHU rats; *P < 0.05: difference between N and CHU in normoxia or hypoxia.

By contrast with the effects of DPCPX on the adenosine-evoked response in CHU rats (see Fig. 4), DPCPX had no effect on the hypoxia-induced fall in ABP, or on the increase in IntFVC evoked by acute hypoxia in CHU rats. However, the hypoxia-induced bradycardia was significantly attenuated (Fig. 5). Given the marked contrast between this result and our previous findings in N rats over many years (e.g. Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Ray & Marshall, 2005), we tested the effect of DPCPX (0.1 mg kg−1i.v.) on the pattern of response evoked by hypoxia in one N rat of the present study. As in our previous studies, DPCPX reduced the hypoxia-induced increase in IntFVC from 5.05 to 0.72 conductance units (CU), the fall in MAP from 44 mmHg to 23 mmHg and the overall bradycardia of 2 bpm was reversed into a tachycardia of 42 bpm. Thus, there was no reason to suppose that this particular batch of DPCPX was ineffective.

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate for the first time the effect of developmental programming induced by CHU in the second half of gestation on the pattern of cardiovascular response evoked by acute systemic hypoxia and adenosine in the adult male offspring. The ability of CHU to induce a programming effect has been shown previously in terms of the anatomical effect of relative brain sparing coupled with general growth retardation (de Grauw et al. 1986) and also by the studies of Williams et al. (2005a,b);, which showed altered vascular responsiveness to both vasoconstrictors and vasodilators in isolated arterial vessels taken from neonatal and adult male CHU rats. We show that in adult male CHU rats, acute systemic hypoxia results in skeletal muscle vasodilatation as in N rats, but the role of adenosine is altered. In N rats, stimulation of adenosine A1 receptors plays a major role in the hypoxia-induced muscle vasodilatation, but this is not the case in CHU rats, even though infusion of adenosine can induce A1-mediated muscle vasodilatation.

Effect of programming on baselines

Exposure of the pregnant mother to developmental programming stimuli has been reported to induce a higher level of resting blood pressure in the adult offspring (Lamireau et al. 2002) in some models. In different models of developmental programming, this has been attributed to a range of influences, including altered vascular function (Williams et al. 2005b), altered cardiac performance (Corstius et al. 2005) or altered nephron number (Woods et al. 2001). In the present study, at 9–10 weeks of age, when they are sexually mature young adults, CHU rats showed little tendency to exhibit higher ABP than N rats, at least under Saffan or Alfaxan anaesthesia. The HR and FVC were also not significantly different between CHU and N rats, although both variables tended to be higher than in N rats. Thus, the present results do not contradict evidence that raised ABP is a trait common to several different models of developmental programming (see Pladys et al. 2005; Woods & Weeks, 2005) and raise the possibility that there are also changes in the distribution of cardiac output that may be revealed in future studies. It should be noted that at 12 weeks of age, conscious, unrestrained CHU rats that had been exposed to more severe hypoxia during pregnancy than those of the present study (10% O2 from days 5–20 of pregnancy) also showed similar resting levels of ABP to age-matched N rats (Peyronnet et al. 2002). The difference between the results of the present study and some others might relate to our use of anaesthesia, to a general state of arousal in both the CHU and N rats in the study of Peyronnet et al. (2002), and/or to the different rat strains (Sprague–Dawley vs. Wistar).

Responses evoked by systemic hypoxia

As described in the Introduction, in N rats acute systemic hypoxia produces a multifaceted response including an increase in muscle sympathetic nerve activity driven by peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation (Marshall, 1994) and release of endothelium-derived vasodilator factors which result in a fall in ABP, and an increase in FVC that is partly mediated by adenosine acting on A1 not A2A receptors (Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Ray & Marshall, 2005). This is generally accompanied by tachycardia that wanes towards or below control level (Neylon & Marshall, 1991; Thomas & Marshall, 1994; Thomas et al. 1994). The initial tachycardia has been attributed to a baroreceptor-reflex response to the fall in ABP and to the secondary effects of hyperventilation on HR, while the secondary bradycardia has been attributed to waning of the hyperventilation, mediated partly by stimulation of central neural A1 receptors, and partly to the local effects of adenosine on cardiac A1 receptors (Thomas & Marshall, 1994; Thomas et al. 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999).

Seen in this context, a major new finding of the present study is that CHU rats respond to acute systemic hypoxia with a similar pattern of response to the N rats, with a similar magnitude of fall in ABP, increase in FVC and similar biphasic HR response. The fact that the secondary bradycardia was more pronounced in the CHU rats of Group 4 than in those of Group 2 is not unexpected for our previous studies have shown differences between groups of N rats in the relative balance of the initial tachycardia and secondary bradycardia (cf. Neylon & Marshall, 1991; Thomas et al. 1994). Therefore, there is no reason to suggest that the overall response to acute systemic hypoxia at maturity is altered by CHU. However, a second major finding of the present study is that in direct contrast to N rats (Thomas et al. 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999; Ray & Marshall, 2005), neither 8-SPT, which is non-selective between adenosine receptor subtypes, nor DPCPX, which has high selectivity for A1 receptors, affected the hypoxia-induced changes in ABP, or FVC in CHU rats. Nevertheless, consistent with our findings on N rats (Thomas et al. 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999), DPCPX attenuated the secondary waning of HR in CHU rats, whereas 8-SPT did not.

Three obvious proposals can be made from these findings. Firstly, adenosine does not contribute to hypoxia-induced dilatation in skeletal muscle in CHU rats by acting on A1 receptors, nor it appears, by acting on A2A or any other subgroup of adenosine receptors. Secondly, since the magnitude of the hypoxia-evoked vasodilatation was not significantly different in CHU rats and N rats, vasodilators other than adenosine must play a larger role in CHU than N rats. Thirdly, adenosine does nevertheless contribute to the secondary bradycardia of hypoxia in CHU rats. Indeed, given DPCPX, which is selective for A1 receptors, can cross the blood–brain barrier (Bisserbe et al. 1992) whereas 8-SPT, which is non-selective between A1 and A2A receptors, cannot (Evoniuk et al. 1987), it seems reasonable to propose that DPCPX attenuated the secondary bradycardia by acting on central A1 receptors to attenuate the secondary waning of the respiratory response to hypoxia (Wessberg et al. 1984). The changes in blood gases accord with this proposal, given the strong tendency for  to increase in normoxia after DPCPX and for

to increase in normoxia after DPCPX and for  to be lower in normoxia and hypoxia in CHU rats after DPCPX, as we reported previously in N rats (Bryan & Marshall, 1999), consistent with removal of a central inhibitory effect of adenosine on respiration. Clearly, we cannot exclude the possibility that DPCPX also affected the HR response to hypoxia by blocking the action of adenosine on cardiac A1 receptors as in N rats (see Thomas et al. 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999).

to be lower in normoxia and hypoxia in CHU rats after DPCPX, as we reported previously in N rats (Bryan & Marshall, 1999), consistent with removal of a central inhibitory effect of adenosine on respiration. Clearly, we cannot exclude the possibility that DPCPX also affected the HR response to hypoxia by blocking the action of adenosine on cardiac A1 receptors as in N rats (see Thomas et al. 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999).

The findings discussed so far do not distinguish between the possibilities that (i) A1 receptors are not expressed in skeletal muscle vasculature of CHU rats and (ii) adenosine is not released in skeletal muscle vasculature during acute systemic hypoxia. The results we obtained with adenosine infusion shed light on these alternatives. For in CHU rats adenosine infusion induced a fall in ABP and increase in FVC and DPCPX attenuated the fall in ABP and abolished the increase in FVC. This indicates that there are functional A1 receptors in skeletal muscle vasculature of CHU, as in N rats, (Bryan & Marshall, 1999), and therefore allows the proposal that it is the release of adenosine in skeletal muscle during systemic hypoxia that is defective in CHU rats. On the other hand, the finding that adenosine infusion evoked an increase in HR in CHU rats after DPCPX, but not before, is consistent with the finding of Bryan & Marshall (1999) that adenosine infusion in N rats induced a bradycardia that was reversed to tachycardia by DPCPX. It may be that the baroreceptor-mediated tachycardia induced by the adenosine-induced fall in MAP is stronger, or the direct effect of cardiac A1 receptor stimulation is weaker, in CHU than N rats. But, whichever is the case, the results are consistent with the proposal made above that adenosine that is locally released in the heart may contribute to the secondary bradycardia of systemic hypoxia in CHU rats, by acting on A1 receptors.

Mechanisms underlying muscle vasodilatation

Previous studies have indicated that in systemic hypoxia, adenosine is released from the endothelium rather than the skeletal muscle fibres (Mian & Marshall, 1991; Mo & Ballard, 2001). Our evidence indicates that the release of adenosine reflects the competition between NO and O2 for the same binding site on mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase of endothelial cells, such that a relative lack of O2 not only allows NO to decrease ATP synthesis (see Brown, 2000), but causes adenosine release (see Edmunds et al. 2003). The adenosine then acts on endothelial A1 receptors to cause synthesis and release of NO, which induces muscle vasodilatation (Ray et al. 2002; Ray & Marshall, 2005). Considered in this context, the present findings raise the possibility that in CHU rats, the role of NO in causing adenosine release from endothelium and possibly the ability of adenosine to cause NO-mediated dilatation via A1 or indeed A2A receptors (see Ray et al. 2002) is compromised. The fact that intra-arterially infused adenosine was able to induce A1-mediated vasodilatation in CHU rats does not argue against the latter possibility for intra-arterial adenosine can evoke muscle vasodilatation via A1 receptors in N rats even after NO synthase blockade, presumably by stimulating receptors on the vascular smooth muscle (see Edmunds et al. 2003).

The mesenteric arteries of 4- and 7-month-old CHU rats showed no obvious decrease in eNOS expression relative to those of control rats, but at 7 months the contribution of NO to endothelium-dependent relaxation of mesenteric arteries of CHU rats was greatly impaired relative to N rats. Further, in CHU mesenteric arteries only, endothelium-dependent relaxation was augmented by SOD, suggesting NO availability was attenuated by increased superoxide production (Williams et al. 2005b). Similarly, we recently provided evidence that H2O2 generated from superoxide exerts a tonic vasoconstrictor influence in muscle vasculature of CHU, but not N rats (Rook et al. 2009). Thus, it seems reasonable to propose that the availability of NO is reduced in skeletal muscle vasculature of CHU rats secondary to an increase in superoxide production, as suggested for mesenteric arteries in CHU rats (Williams et al. 2005b). If this is so, then a decrease in the availability of NO to bind to endothelial cytochrome oxidase would be expected to decrease the sensitivity of the ‘sensing’ mechanism to a fall in  such that adenosine would be less readily released in response to a given level of systemic hypoxia (see Brown, 2000; Edmunds et al. 2003). Clearly, this important proposal requires investigation in future studies.

such that adenosine would be less readily released in response to a given level of systemic hypoxia (see Brown, 2000; Edmunds et al. 2003). Clearly, this important proposal requires investigation in future studies.

Since adenosine did not contribute to the hypoxia-induced muscle vasodilatation in CHU rats, the question arises as to how this dilatation was mediated. In previous studies on N rats, we showed that endothelial generation of prostacyclin (PGI2) is an essential intermediate in the pathway by which adenosine acts on endothelial A1 receptors to stimulate NO synthesis and induce muscle vasodilatation (Ray et al. 2002). In N rats, there was also the possibility that PGI2 is released independently of adenosine in skeletal muscle during systemic hypoxia (Ray et al. 2002), as has been shown when isolated muscle arterioles are made hypoxic in vitro (Messina et al. 1992; Frisbee et al. 2002). Thus, it is possible that such PGI2 makes a substantial contribution to hypoxia-induced muscle vasodilatation in CHU rats. The dilatation might also be mediated by H2O2 generated by dismutation of superoxide. However, our recent findings indicate that inhibition of SOD has no effect on hypoxia-induced muscle vasodilatation in CHU rats (Rook et al. 2009). Further possible mechanisms to couple oxygen sensing with hypoxia-induced vasodilatation include a greater role in CHU rats of endothelium-dependent hyperpolarising factor, ATP release from erythrocytes (Dietrich et al. 2000) or S-nitrosohaemoglobin (Diesen et al. 2008); however, evaluation of their roles would require a new investigation.

In summary, we have demonstrated in the rat, that prenatal hypoxia has long lasting effects on vascular function in skeletal muscle of the adult male offspring. Given that changes in FVC reflect changes in the diameter of arterioles in skeletal muscle that determine gross muscle vascular resistance and influence distribution of blood flow to the capillaries (see Hebert & Marshall, 1988), this is the first study as far as we are aware to demonstrate that CHU changes responsiveness at this level of the microvascular tree in vivo. Our results demonstrate that the overall magnitude of vasodilator responses evoked in muscle by acute systemic hypoxia is similar in CHU and N rats, but the mechanisms underlying the responses are different. Importantly, the mechanism that allows adenosine release in systemic hypoxia seems to be defective in CHU rats and the contribution of adenosine to hypoxia-induced muscle vasodilatation is replaced by factors other than adenosine. Since this implies a major change from normal endothelial function, it may have far reaching consequences for cardiovascular regulation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the British Heart Foundation for this study (PG/03/127).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ABP

arterial blood pressure

- CHU

chronic systemic hypoxia in utero

- CVA

caudal ventral tail artery

- FBF

femoral blood flow

- FVC

femoral vascular conductance

- HR

hear rate

- IntFVC

integrated femoral vascular conductance

- IUGR

intrauterine growth retardation

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- NR

nutrient restricted

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Author contributions

AC and JMM designed the experiments, AC collected and analysed the data. AC and JMM interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version for publication.

References

- Barker DJP. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1995;311:171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJP. In utero programming of chronic disease. Clin Sci. 1998;95:115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram CE, Hanson MA. Animal models and programming of the metabolic syndrome. Brit Med Bull. 2001;60:103–121. doi: 10.1093/bmb/60.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisserbe JC, Pascal O, Deckert J, Maziere B. Potential use of DPCPX as probe for in vivo localisation of brain A1 adenosine receptors. Brain Res. 1992;599:6–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90845-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC. Nitric oxide as a competitive inhibitor of oxygen consumption in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;168:667–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan PT, Marshall JM. Adenosine receptor subtypes and vasodilatation in rat skeletal muscle during systemic hypoxia: a role for A1 receptors. J Physiol. 1999;514:151–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.151af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdge GC, Dunn RL, Wootton SA, Jackson AA. Effect of reduced dietary protein intake on hepatic and plasma essential fatty acid concentrations in the adult female rat: effect of pregnancy and consequences for accumulation of arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids in fetal liver and brain. Br J Nutr. 2002;88:379–387. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coney AM, Marshall JM. Contribution of adenosine to the depression of sympathetically evoked vasoconstriction induced by systemic hypoxia in the rat. J Physiol. 2003;549:613–623. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coney AM, Marshall JM. Contribution of α2-adrenoceptors and Y-1 neuropeptide Y receptors to the blunting of sympathetic vasoconstriction induced by systemic hypoxia in the rat. J Physiol. 2007;582:1349–1359. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corstius HB, Zimanyi MA, Maka N, Herath T, Thomas W, Van Der Laarse A, Wreford NG, Black MJ. Effect of intrauterine growth restriction on the number of cardiomyocytes in rat hearts. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:796–800. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000157726.65492.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Grauw TJ, Myers RE, Scott WJ. Fetal growth-retardation in rats from different levels of hypoxia. Biol Neonate. 1986;49:85–89. doi: 10.1159/000242515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesen DL, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Hypoxic vasodilation by red blood cells: Evidence for an S-nitrosothiol-based signal. Circ. Res. 2008;103:545–553. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich HH, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS, Dacey RG., Jr Red blood cell regulation of microvascular tone through adenosine triphosphate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1294–H1298. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds NJ, Moncada S, Marshall JM. Does nitric oxide allow endothelial cells to sense hypoxia and mediate hypoxic vasodilatation?In vivo and in vitro studies. J Physiol. 2003;546:521–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evoniuk G, Von Borstel RW, Wurtman RJ. Antagonism of the cardiovascular effects of adenosine by caffeine or 8-(p-sulphophenyl)-theophylline. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;240:428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisbee JC, Maier KG, Falck JR, Roman RJ, Lombard JH. Integration of hypoxic dilation signaling pathways for skeletal muscle resistance arteries. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R309–R319. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00741.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert MT, Marshall JM. Direct observations of the effects of baroreceptor stimulation on skeletal-muscle circulation of the rat. J Physiol. 1988;400:45–59. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoet JJ, Hanson MA. Intrauterine nutrition: its importance during critical periods for cardiovascular and endocrine development. J Physiol. 1999;514:617–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.617ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamireau D, Nuyt AM, Hou X, Bernier S, Beauchamp M, Gobeil F, Lahaie I, Varma DR, Chemtob S. Altered vascular function in fetal programming of hypertension. Stroke. 2002;33:2992–2998. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000039340.62995.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC. Hypertension induced by foetal exposure to a maternal low- protein diet, in the rat, is prevented by pharmacological blockade of maternal glucocorticoid synthesis. J Hypertens. 1997a;15:537–544. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC. Maternal carbenoxolone treatment lowers birthweight and induces hypertension in the offspring of rats fed a protein-replete diet. Clin Sci. 1997b;93:423–429. doi: 10.1042/cs0930423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louey S, Thornburg KL. The prenatal environment and later cardiovascular disease. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81:745–751. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Peripheral chemoreceptors and cardiovascular regulation. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:543–594. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina EJ, Sun D, Koller A, Wolin MS, Kaley G. Role of endothelium-derived prostaglandins in hypoxia-elicited arteriolar dilation in rat skeletal muscle. Circ Res. 1992;71:790–796. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.4.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian R, Marshall JM. The role of adenosine in dilator responses induced in arterioles and venules of rat skeletal muscle by acute systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1991;443:499–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo FM, Ballard HJ. The effect of systemic hypoxia on interstitial and blood adenosine AMP, ADP and ATP in dog skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2001;536:593–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0593c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JL. Sheep models of intrauterine growth retardation: Fetal adaptations and consequences. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:730–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neylon M, Marshall JM. The role of adenosine in the respiratory and cardiovascular response to systemic hypoxia in the rat. J Physiol. 1991;440:529–545. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki T, Nishina H, Hanson MA, Poston L. Dietary restriction in pregnant rats causes gender-related hypertension and vascular dysfunction in offspring. J Physiol. 2001;530:141–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0141m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyronnet J, Dalmaz Y, Ehrstrom M, Mamet J, Roux JC, Pequignot JM, Thoren HP, Lagercrantz H. Long-lasting adverse effects of prenatal hypoxia on developing autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular parameters in rats. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:5–6. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyronnet J, Roux JC, Mamet J, Perrin D, Lachuer J, Pequignot JM, Dalmaz Y. Developmental plasticity of the carotid chemoafferent pathway in rats that are hypoxic during the prenatal period. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2865–2872. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pladys P, Sennlaub F, Brault S, Checchin D, Lahaie I, Le NLO, Bibeau K, Cambonie G, Abran D, Brochu M, Thibault G, Hardy P, Chemtob S, Nuyt AM. Microvascular rarefaction and decreased angiogenesis in rats with fetal programming of hypertension associated with exposure to a low-protein diet in utero. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1580–R1588. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00031.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray CJ, Abbas MR, Coney AM, Marshall JM. Interactions of adenosine, prostaglandins and nitric oxide in hypoxia-induced vasodilatation: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Physiol. 2002;544:195–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray CJ, Marshall JM. Measurement of nitric oxide release evoked by systemic hypoxia and adenosine from rat skeletal muscle in vivo. J Physiol. 2005;568:967–978. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook WHR, Marshall JM, Coney AM. Chronic hypoxia in utero (CHU) increases superoxide production in adult rat skeletal muscle vasculature. Proc Physiol Soc. 2009;15:C1. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MR, Marshall JM. Studies on the roles of ATP, adenosine and nitric oxide in mediating muscle vasodilatation induced in the rat by acute systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1996;495:553–560. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Elnazir BK, Marshall JM. Differentiation of the peripherally mediated from the centrally mediated influences of adenosine in the rat during systemic hypoxia. Exp Physiol. 1994;79:809–822. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1994.sp003809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Marshall JM. Interdependence of respiratory and cardiovascular changes induced by systemic hypoxia in the rat – the roles of adenosine. J Physiol. 1994;480:627–636. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Marshall JM. A study on rats of the effects of chronic hypoxia from birth on respiratory and cardiovascular responses evoked by acute hypoxia. J Physiol. 1995;487:513–525. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler CC, Amatya S, McClaskey C, Ghatpande S, Fredholm BB, Rivkees SA. A1 adenosine receptors play an essential role in protecting the embryo against hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9697–9702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703557104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessberg P, Hedner J, Hedner T, Persson B, Jonason J. Adenosine mechanisms in the regulation of breathing in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;106:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SJ, Campbell ME, McMillen IC, Davidge ST. Differential effects of maternal hypoxia or nutrient restriction on carotid and femoral vascular function in neonatal rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005a;288:R360–R367. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00178.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SJ, Hemmings DG, Mitchell JM, McMillen IC, Davidge ST. Effects of maternal hypoxia or nutrient restriction during pregnancy on endothelial function in adult male rat offspring. J Physiol. 2005b;565:125–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Nyengaard JR, Rasch R. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:460–467. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods LL, Weeks DA. Prenatal programming of adult blood pressure: role of maternal corticosteroids. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R955–R962. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00455.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]