Abstract

This article describes the various methods of endovascular management of high-flow arteriovenous malformations. Concepts of patient management and various therapies for vascular malformations are discussed. Nontraumatic acquired arteriovenous malformations, arteriovenous fistulae, and endovascular treatment of arteriovenous malfromations are described.

Keywords: Arteriovenous malformations, arteriovenous fistula

Vascular malformations constitute some of the most difficult diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas that can be encountered in the practice of medicine. The clinical presentations are extremely protean and can range from an asymptomatic birthmark to fulminant life-threatening congestive heart failure. Attributing any of these varied symptoms with which a patient may present to a vascular malformation can be challenging to the most experienced clinician. Compounding this problem is the extreme rarity of these vascular lesions. If a clinician sees one patient with this presentation every few years, it is extremely difficult to gain a learning curve to diagnose and optimally treat the illness. Typically, these patients bounce from clinician to clinician only to experience disappointing outcomes, complications, and recurrence or worsening of their presenting symptoms.

Vascular malformations were initially treated by surgeons alone. The early rationale of proximal arterial ligation of arteriovascular malformations (AVMs) proved totally futile as the phenomenon of neovascular recruitment reconstituted arterial inflow to the AVM nidus. Microfistulous connections became macrofistulous feeders. Complete surgical extirpation of a vascular malformation can be very difficult and, at times even hazardous, necessitating suboptimal partial resections. Partial resections can cause a good initial clinical response that may last for some time. However, very often the patient's presenting symptoms recur or worsen at follow-up.1,2,3 Because of the significant blood loss that frequently accompanies surgery, the skills of interventional radiologists were eventually employed to embolize these vascular malformations preoperatively. This not only allowed more complete resections, it also decreased blood loss during surgery. However, complete removal of a vascular malformation is still a difficult issue and may not always be possible. Various authors have published that only ∼20% of malformations may be amenable to complete extirpation with surgery.2,4,5

According to D. Emerick Szilagyi, M.D., former Editor for the Journal of Vascular Surgery, “…with few exceptions, their [vascular anomalies] cure by surgical means is impossible. We intuitively thought that the only answer of a surgeon to the problem of disfiguring, often noisome, and occasionally disabling blemishes and masses, prone to cause bleeding, pain, or other unpleasantness, was to attack them with vigor and with the determination of eradicating them. The results of this attempt of radical treatment were disappointing.”2 Indeed, of the 82 patients initially evaluated in this patient series, only 18 patients were operated upon; at follow-up, 10 were improved, 2 were the same, and 6 were worse.

This patient series indicates the enormity of the problem posed by vascular malformations. They are best treated in medical centers where these patients are seen regularly. The interventional radiologist or surgeon who occasionally evaluates a patient every year or so will never gain enough experience to manage these challenging lesions. All too frequently the patient ultimately pays for the physician's initial enthusiasm, inexperience, and lack of necessary clinical backup. For optimal treatment, a vascular malformation team should be in place. The various surgical, medical, and interventional specialties function together, much like a tumor board of specialists. Only when patients are seen and treated regularly can experience be gained, rational decisions made, and patient care optimized. It cannot be emphasized enough that as a group, vascular malformations pose one of the most difficult challenges in the practice of medicine. A cavalier approach to their management will always lead to significant complications and dismal patient outcomes.

CONCEPTS IN PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Vascular malformations are congenital lesions that are present at birth, whether or not they are evident clinically, and grow commensurately with the child. The collective term vascular malformation encompasses any malformed blood vessel of any vascular element including arteries, capillaries, veins, and lymphatics. Posttraumatic arteriovenous fistulae (AVF) are different in that they are an acquired lesion, although they may appear similar radiographically.6,7 A thorough clinical examination and history can usually establish the diagnosis of hemangioma or vascular malformation.

Color Doppler imaging (CDI) is an essential tool in the diagnostic evaluation of vascular malformations. Both high-flow lesions (AVMs, AVFs) and low-flow lesions (venous malformations, lymphatic malformations) can be diagnosed accurately. Furthermore, CDI is an important noninvasive method for monitoring patients who have undergone therapy. Documentation of increased arterial flow rates prior to therapy and decreased arterial flow rates after therapy is important physiological information. In low-flow malformations, persistent documentation of thrombosis can be imaged and accurately assessed.8

Computed tomography (CT), although helpful in the diagnostic evaluation, is less useful than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Unlike CT, MRI easily distinguishes between high-flow and low-flow vascular malformations. Furthermore, the anatomic relationships of the vascular malformation to adjacent nerves, muscles, tendons, solid organs, bone, and subcutaneous fat allow a complete assessment. MRI is also an excellent noninvasive method for observing patients to determine the efficacy of therapy, often obviating repetitive arteriography and venography.9 CT has its main role in intraosseous vascular malformations and determination of the extent of bone involvement.

After the diagnosis is established, the next major hurdle is to determine whether therapy is needed. Usually the presenting patient complaint warrants treatment. In the unusual case, the patient may have a high-flow AVM discovered serendipitously that is asymptomatic. However, upon closer evaluation, young patients may not be symptomatic from a high output cardiac state. This high output cardiac state can be the sole criterion for determining that therapy is required. Consultation with multiple medical and surgical specialists may be required to determine if treatment ultimately is warranted.

With the use of ethanol as an embolic agent to treat vascular malformations, our patients require general anesthesia. At times, Swan-Ganz line and arterial line monitoring may be necessary when treating larger lesions. Pulmonary artery pressures then can be constantly monitored to determine if abnormal elevation of the pulmonary pressures occurs during the procedure. If high pulmonary pressures occur, then the embolization procedure can be stopped to allow the pulmonary pressures to normalize. If the pressures are high enough, the infusion of nitroglycerine through the Swan-Ganz catheter can help lower the pulmonary artery pressures to normalcy. Adenosine is another useful agent to lower pulmonary pressures without affecting systemic pressures. General anesthesia is a requirement because intravascular ethanol is extremely painful and an embolization procedure could be compromised if a patient is moving constantly. Postprocedure, the patients are revived from anesthesia and sent to the recovery room for temporary observation. After they are deemed stable, they are then usually sent to the routine hospital floor. Postprocedure medical management consists of decadron therapy to manage the swelling that occurs with acute thrombosis following embolization. Patients are observed overnight and discharged the following morning unless a complication occurs that requires management.

Patients usually exhibit focal postprocedural swelling in the area of the embolized malformation. In most patients, the majority of the swelling will resolve within 1 to 2 weeks. In those patients with lower extremity and foot malformations, swelling may last longer because the leg and foot are both dependent and weight-bearing structures. Usually after 4 weeks all swelling is resolved and the patient, being at his or her new baseline, is ready for follow-up therapy as necessary.

After serial therapy, MRI and CDI can be used to document the efficacy of therapy. In those patients who present with a pain syndrome, serial devascularization of the malformation will usually diminish or completely treat the pain. At the author's institution, patients with residual pain undergo neurostimulation therapy with Synaptic 2000, a neurostimulator pain control device (Synpatic Corp., RFP Inc., Aurora, CO).10 This unique, noninvasive device has proven very helpful in controlling residual pain in selective patients. It has also been useful in reducing the need for oral narcotic medications in patients presenting with pain. Additional applications with this device have been to aid nerve injury recovery, stimulate microvascular structures in the ischemic tissues, decrease swelling, and aid tissue healing postinjury. Some patients may also benefit from medical management with drugs such as gabapentin.

ENDOVASCULAR THERAPY OF VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

Embolization procedures have evolved as one of the corner stones of modern interventional radiology. The extensive array of catheters, guidewires, endovascular embolic materials, and imaging systems are a tribute to the hard work, insight, and imagination of the many dedicated investigators in this area. Because of significant laboratory research, clinical research, and extensive clinical experience, the judicious use of embolization is a reality in modern clinical practice that will continue to become more common.

There are many embolic agents that are used in various clinical scenarios. The choice of agent depends on several factors: the vascular territory to be treated, the type of abnormality being treated, the possibility of superselective delivery of an occlusive agent, the goal of the procedure, and the permanence of the occlusion. For vascular malformations, permanence is a significant issue. It has been documented in the literature that embolization with polyvinyl alcohol, tissue adhesives (glues), fibered coils, and the like are rarely curative, but can provide temporary palliation.11,12,13 With the advent of the use of ethanol, cures at long-term follow-up have been documented by many authors.10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 The judicious use of ethanol as an embolic agent has revolutionized our abilities to permanently cure these lesions in the soft tissues, organs, bone, and brain.10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40

ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATIONS

AVMs are congenital vascular anomalies typified by hypertrophied inflow arteries shunting through a primitive vascular nidus (from the Latin nidus and nidi, meaning nest) into tortuous, dilated, usually multiple outflow veins. No intervening capillary bed is present. AVMs can occur in any soft tissue, in bone, in solid organs, or the central nervous system including the brain, spinal cord, and dura.

AVMs can be very complex, with many arterial inflow arteries supplying the lesion with multiple outflow veins. They also can be somewhat simpler with a single inflow artery. In large AVMs that have single outflow vein physiology, cure can be effected through a retrograde vein approach to the nidus, which is usually a large venous sac with multiple inflow arteries throughout its vascular venous wall. The majority of AVMs, however, do not have this single outflow vein physiology and require transarterial routes or direct puncture routes to access the nidus itself.

AVMs can have several forms of distinctive angioarchitecture. The most common form is the nidal form whereby multiple inflow arteries converge on the nidus (Fig. 1). In another form, multiple arteries converge on a venous sac simulating an AVM nidus; this AVM variant can have a single outflow vein angioarchitecture (Fig. 2). The third type of angioarchitecture for arteriovenous malformation is the infiltrative type (Fig. 3). This type of AVM infiltrates the tissues involved and does not have a distinct nidal type form. This is a very complex AVM that diffusely infiltrates a tissue and usually causes tissue enlargement. The fourth type of high-flow lesion is the simple single artery to vein fistula.

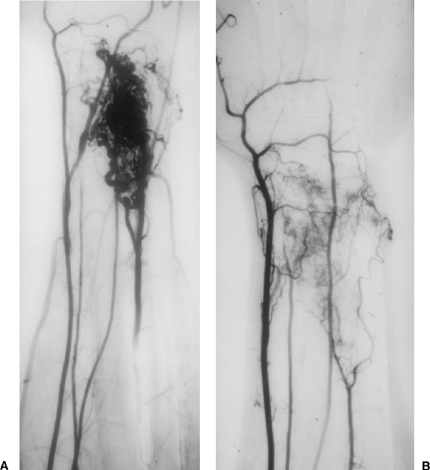

Figure 1.

A 24-year-old male with an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) over dorsum of wrist causing severe pain with movement. (A) Brachial artery arteriogram. Note the presence of normal radial artery, median artery, ulnar artery, and abnormal primitive artery arising from the brachial artery coursing to the dorsum of the forearm and wrist supplying AVM. Note nidal form of angioarchitecture. (B) Brachial artery arteriogram at 4-month follow-up. Note absence of AVM and normalcy of radial, median, and ulnar arteries. Note shrinkage in size of the primitive artery in response to absence of AV shunting. Area of healing hyperemia also is noted in the area of the treated AVM.

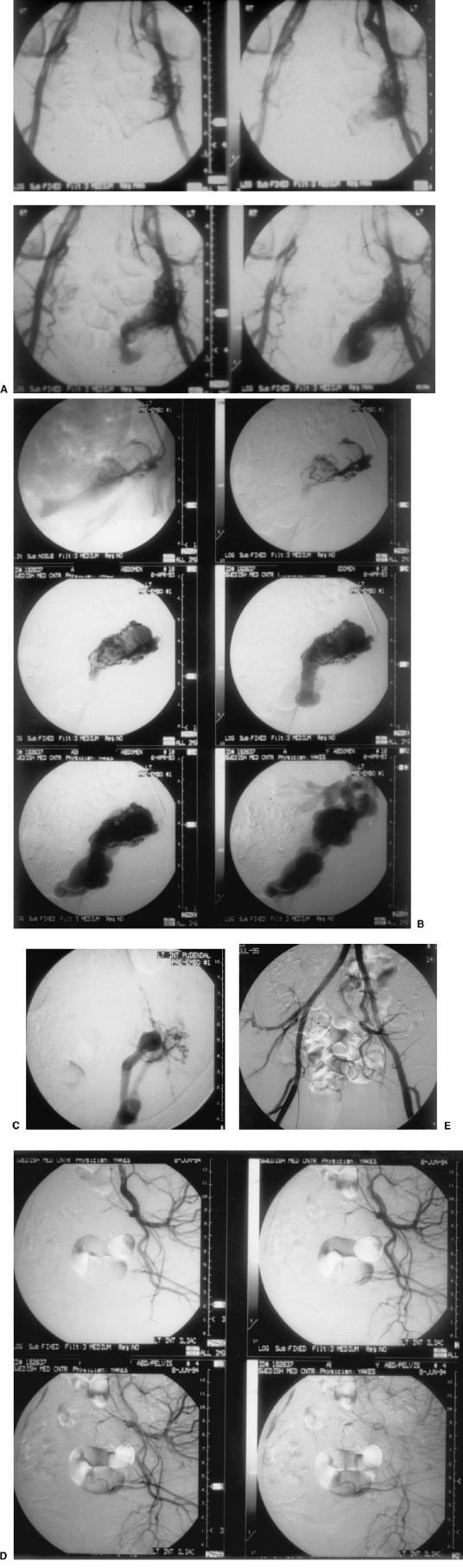

Figure 2.

A 34-year-old female with painful intercourse due to left pelvic arteriovenous malformation (AVM). (A) Pelvic arteriogram documenting left pelvic AVM. (B) Selective left internal pudendal arteriogram documenting fistulous connections to a single outflow vein angioarchitecture. (C) Superselective microcatheter position pre-embolization. Note microfistulous connections to single outflow vein angioarchitecture. (D) Left internal iliac arteriogram at 1-year follow-up documenting cure of AVM. (E) AP pelvis arteriogram at 2-year follow-up documenting persistent cure of AVM. The patient had no further pelvic pain symptoms.

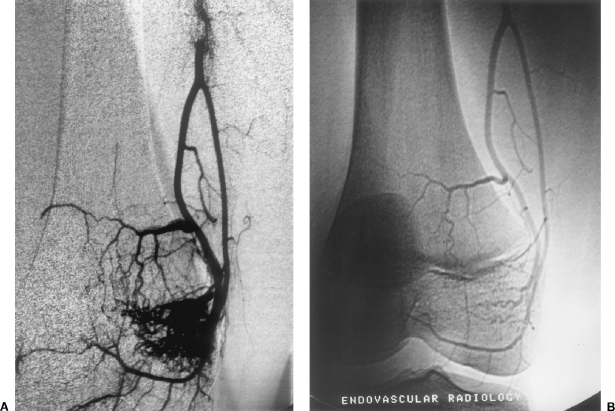

Figure 3.

A 12-year-old female with painful knee due to intraosseous infiltrative arteriovenous malformation (AVM) of medial femur condyle. Treatment was performed with Prof. Krasnodar Ivancev, M.D., in Malmo, Sweden, University of Lund, Department of Endovascular Surgery. (A) Selective arteriogram of profunda femoris artery branch supplying bone AVM. (B) One-year follow-up arteriogram documenting persistent cure of AVM. The patient had no further symptoms.

Symptoms of AVMs are usually referable to the involved anatomic location. If the location involves bone, then bony overgrowth, limb length discrepancy, pathologic fractures due to bone wasting, and pain syndromes can occur. An AVM involving the mandible and/or maxilla can cause tooth loss and gingival hemorrhages, which can be severe. There also is a usual cystic space and thinning of bone within the mandibular compartment of AVM. In patients with AVM of bone of the extremities, the presence of multiple AVMs of that affected extremity is common. Gorham's disease, or Gorham-Stout syndrome, is a vascular malformation (usually low-flow type) causing a vanishing bone pattern on radiography.

AVMs can involve mucosal surfaces of the biliary tract, gastrointestinal tract, aerodigestive system, and the skin. If tissues close to the skin or mucosal surface are involved, nonhealing ulcers can occur that can lead to infections and bleeding. Skin grafting will be of no avail because when the underlying normal skin dies, the much weaker skin graft will most certainly fail. Furthermore, hemorrhage can be a significant problem with ulcerations on mucosal surfaces, often requiring blood transfusions.

With a large AVM and central position within the pelvis, abdomen, chest, or shoulder, high-output cardiac states can occur due to the large size of the shunting lesion. The lesion is characterized by low peripheral resistance and a high cardiac index and cardiac output. If a patient goes many years without treatment while suffering this high-output cardiac state, long-term consequences to the myocardium are possible. Patients may look clinically stable in their youth despite the high-output state; however, at a later age they can develop exercise intolerance and other problems. At our institution, we place Swan-Ganz lines to predict accurately if a patient with an AVM has a high-output cardiac state. Noninvasive cardiac measurements will give erroneous data and do not correlate well with the direct Swan-Ganz measurements. Thus, we have abandoned noninvasive cardiac tests for this evaluation because of their constant failure to give an accurate diagnosis.

Other symptoms that occur with AVMs are pain, progressive nerve deterioration or palsy, disfiguring mass, tissue ulceration, hemorrhage, impairment of limb function, limiting claudication, and joint hemorrhages, among others. In fact, attributing any one of these symptoms to a high-flow AVM can be challenging to the most experienced clinician.

ENDOTHELIAL CELL THEORY

Without complete extirpation of a vascular malformation, there is an almost uniform tendency for the malformation to recur and for symptoms to worsen. The same can be encountered with embolization techniques if the AVM nidus is not completely obliterated. The reason for this failure to cure partially embolized AVMs is at the cellular level.

Like all blood vessels of the body, AVMs are lined by endothelial cells. When thrombosed with embolic agents or when their blood source interrupted by proximal arterial ligations, endothelial cells sense decreased oxygen tension in their environment. The cell then sends out two factors to rectify the situation and return its state of a normal oxygenation level. Chemotactic factors are released that cause a cellular infiltration from tissue into the thrombosed blood vessel. This cellular infiltrate then physically removes the thrombosed elements in the blood vessel. The open channels may then become re-endothelialized. This is termed recanalization, and is the method by which previously thrombosed vascular channels are reopened. The other factor secreted by the endothelial cell to rectify its O2 deprivation is angiogenesis factor. This factor has not as yet been discovered in its chemical form, but we know it exists because of results from various cancer studies as well as peripheral vascular disease models. After sensing decreased oxygen tension because of intravascular thrombosis of an AVM nidus, the endothelial cell sends out this angiogenesis factor and stimulates a neovascular response. In an attempt to revascularize the thrombosed area and thus increase the oxygen tension level, new blood vessel formation occurs. Microfistulous arteries can become macrofistulous connections to the AVM. This neovascular stimulation phenomenon can be very intense. For example, surgery in the brain must be performed quickly before the new blood vessels form and make surgery impossible. These two phenomena of recanalization and neovascular recruitment lead to the recurrence of AVMs.

ENDOVASCULAR TREATMENT OF AVM

Surgery was the initial form of therapy to treat AVMs. Embolization followed by surgery has proved beneficial to patients. However, cure rates are almost nonexistent with this method unless the AVM is very focal and in a safe anatomic area. In surgically difficult anatomic areas, it is problematic, if not impossible for a complete AVM removal to occur. Proximal ligations of arteries and skeletonization of arteries to AVMs also are documented in multiple surgery articles to fail uniformly in treating AVMs. The remaining nidus that was not removed can grow and be even more symptomatic to the patient compared with its preoperative status. This can be very vexing to the patient and physician alike.

Many endovascular occlusive agents have been used to treat AVMs, each of which might provide good palliation. However, the problems of recanalization and neovascular recruitment phenomena cause these agents to fail ultimately. With the use of absolute ethanol as an embolic agent, these phenomena have not been observed. Furthermore, with ethanol ablation of the nidus untreated inflow arterial feeders to the nidus decrease in size because of the absence of the AVM, and subsequently only supply the normal surrounding tissues. CDI has provided physiologic data documenting decreased flow rates through arterial feeders after embolization of the AVM nidus at follow-up evaluation.

In treating AVMs endovascularly, superselective catheter placement is absolutely essential. When it is not possible to approach an AVM and access its nidus with an endovascular approach, then direct percutaneous puncture techniques should be employed. If superselective placement in an AVM nidus is not possible, then the use of ethanol must be avoided. Not infrequently, inflow occlusion might be required to induce some level of decreased flow or vascular stasis in the embolized vessel to allow the full contact of ethanol with the endothelium, maximizing the thrombogenic properties of ethanol. Inflow occlusion can be achieved through the use of occlusion balloon catheters, blood pressure cuffs, tourniquets, and the like. The author empirically uses occlusive techniques for ∼10 minutes. Inflow vascular occlusion techniques might also help in decreasing the total amount of ethanol used to treat an AVM.

Endovascular ablation of AVM with ethanol has ushered in a new era in the therapy of these problematic vascular anomalies.10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 Cures and permanent partial ablations have been well documented. Because neovascular recruitment phenomena and recanalizations have not been observed, partial permanent ablations have led to long-term symptomatic improvement, obviating the need for further treatment. Despite the success that is possible with ethanol, it must be remembered that it is an extremely dangerous intravascular sclerosant that can cause significant complications if it enters the normal circulation. Because it is a liquid agent, it will penetrate to the capillary bed level, excluding all collateral circulation. The tissues then die at the cellular level, and extensive necrosis can occur.

Neovascular recruitment phenomena and recanalizations do not occur after ethanol embolization of AVM because the endothelial cell is destroyed. Following ethanol embolization, the endothelial cells are completely denuded from the vascular wall and their protoplasm is precipitated. Blood proteins are denatured, initiating the clotting cascade. When the vascular wall is denuded of its endothelium and is bare, platelet aggregation occurs with the development of thrombus formation along the vascular wall; the thrombus propagates until total thrombosis of the lumen is noted. This process can take time, therefore the author usually waits at least 10 to 20 minutes before requesting a follow-up arteriogram to determine if any additional ethanol is required to complete the thrombosis. With the destruction of the endothelial cell, the cells are no longer able to send chemotactic factor and angiogenesis factor, which may lead to permanent thrombosis and cure.

The amount of ethanol used in each endovascular procedure is tailored to the flow and volume characteristics of the individual compartment of the AVM lesion. No predetermined amount of ethanol is considered. Contrast injections can be practiced prior to ethanol embolization. The amount of contrast needed to completely displace blood and not reflux into the proximal artery estimates the amount of ethanol required for the embolization. It is unusual to cure an AVM in one session. In the larger lesions, the author prefers to treat individual compartments serially, eventually effecting total treatment over time. We usually wait at least 4 weeks between procedures to allow the patient to return to a new baseline prior to further treatment of the lesion.

ARTERIOVENOUS FISTULAE

Congenital and posttraumatic fistulae are similar to AVMs in that they are high-flow vascular malformations. AVF are characterized by an artery connecting to a draining vein without an intervening capillary bed. Posttraumatic AVF are usually secondary to blunt or penetraing trauma with injury to an artery and adjacent vein. Fistulization between the artery and vein is stimulated by preferential vascular shunting through the AVF from the high-pressure arterial system to the low-pressure venous system. Chronic AVF can be confused with AVMs during arteriography because multiple large inflow arteries can simulate an AVM nidus near the arteriovenous connection. Growth of the lesion can occur over time.

The natural history of AVF can be extremely varied. AVF can remain clinically silent and well tolerated by the patient, as evidenced by the iatrogenic dialysis fistula patient or the asymptomatic renal AVF incidentally found at aortography. If the shunt through an AVF is large, hemodynamic consequences such a cardiomegaly, increased cardiac output, increased cardiac index, and intermittent bouts of congestive heart failure might occur. Pain and swelling might also be a presenting complaint. The vascular steal alone can cause ischemic symptoms to the tissues and organs normally supplied by the feeding artery.

Treatment of AVF requires complete occlusion of the AVF connection. As in treating AVMs, proximal arterial ligations and distal venous ligations usually fail. Surgical ligations are not only futile, but they might remove possible vascular access routes for endovascular treatment. The use of ethanol or ethanol with coils, performed in the same fashion as the treatment of AVMs, has been extremely effective in treating and curing these lesions.

NONTRAUMATIC ACQUIRED ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATION

Nontraumatic acquired AVM is an extremely rare entity that can cause severe pain symptoms, leg swelling, and nonhealing ulcers in the lower extremities. We have treated approximately six patients with this disorder. There is no incident history of blunt or penetrating trauma in any patient. The only common history is some element of venous vascular thrombosis or stenosis. In one patient the venous occlusion problem was not present, but the patient had prior aortoiliac and femoral popliteal arterial surgeries. This entity is not a congenital lesion but is an acquired lesion whereby fistulous arterial connections throughout the length of a vein wall are noted. It is not a single end hole entering into the vein; rather, it is a mini-AVM that forms at the vein wall and then flows into the venous circulation under arterial pressures. Again, these appear to be associated with some form of venous thrombosis or venous outflow restriction. This is very similar to the natural history and formation of the noncongenital dural AV fistula of the dural sinuses in the head; this is the only model in the peripheral vascular system that is similar.

We have treated these patients by total thrombosis of the abnormal diseased vein that is arterialized. In one patient, the author stented the diseased fistulous external iliac vein that compressed the intramural fistulas, resulting in cure. Despite major vein occlusions, the extremity loses its edema and the nonhealing ulcers heal.

SUMMARY

Vascular malformations pose some of the most significant challenges in the practice of medicine today. Peripheral soft tissue malformations, as well as central nervous system malformations, cause unique clinical problems determined in part by their anatomic location. Clinical manifestations of these lesions are extremely protean. The rarity of these lesions makes management extremely difficulty. Thus, the minimal or nonexistent experience of most clinicians in the diagnosis and management of AVMs augments the enormity of the problem, which often leads to misdiagnoses, inappropriate treatments, and poor patient outcomes. Vascular malformations are best treated where a team is in place that regularly sees patients with these malformations. Only then can rational decisions and advancements in treatments occur.

REFERENCES

- Decker D G, Fish C R, Juergens J L. Arteriovenous fistulas of the female pelvis: a diagnostic problem. Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1968;31:799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi D E, Smith R F, Ellliott J P, Hageman J H. Congenital arteriovenous anomalies of the limbs. Arch Surg. 1976;111:423–429. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1976.01360220119020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flye M W, Jordan B P, Schwartz M Z. Management of congenital arteriovenous malformations. Surgery. 1983;94:740–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday A W, Smith E J, Jackson J, Allison D I, Mansfield A O. Indications for surgery for arteriovenous malformations. Br J Surg. 1992;79:361–362. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday A W, Mansfield A O. Arteriovenous malformations: current management approaches. Br J Hosp Med. 1989;42:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trout H H, Tievsky A L, Rieth K G, Druy E M, Giordano J M. Arteriovenous fistulas simulating arteriovenous malformation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97:322–325. doi: 10.1177/019459988709700313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawdahl R B, Routh W D, Vietek J J, McDowell H A, Gross G M, Keller F S. Chronic arteriovenous fistulas masquerading as arteriovenous malformations: diagnostic considerations and therapeutic implications. Radiology. 1989;170:1011–1015. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.3.2916053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F, Stavros A T, Parker S H, et al. Color Doppler imaging of peripheral high-flow vascular malformations before and after ethanol embolotherapy. Chicago: Paper presented at: 76th Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting of the Radiologic Society of North America; November 25–30, 1990.

- Rak K M, Yakes W F, Ray R L, et al. MR imaging of symptomatic peripheral vascular malformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:107–112. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.1.1609682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F. Extremity venous malformations: diagnosis and management. Semin Interv Radiol. 1994;11:332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Widlus D M, Murray R R, White R I, Jr, et al. Congenital arteriovenous malformations: tailored embolotherapy. Radiology. 1988;169:511–516. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.2.3175000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V RK, Mandalam K R, Gupta A K, Kumar S, Joseph S. Dissolution of isobutyl 2-cyanoacrylate on long-term follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;10:135–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y, Matsuhiro K, Nagaki M, Tanioka H. Therapeutic embolization for vascular lesions of the head and neck. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;18:47–49. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(89)80016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F, Pevsner P H, Reed M D, Donohue H J, Ghaed N. Serial embolizations of an extremity arteriovenous malformation with alcohol via direct percutaneous puncture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:1038–1040. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayaski S, Hosaka M, Ishizuka E, Hirokawa M, Matsui K. Arteriovenous malformations of the kidneys: ablation with alcohol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:587–590. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson A M, Rohrer D B, Willcox C W, et al. Absolute ethanol embolization for peripheral AVMs: report of two cures. South Med J. 1988;1:1052–1055. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198808000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F, Haas D K, Parker S H, et al. Alcohol embolotherapy of vascular malformations. Semin Interv Radiol. 1989;6:146–161. [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F, Luethke J M, Parker S H, et al. Ethanol embolization of vascular malformations. Radiographics. 1990;10:787–796. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.10.5.2217971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F, Luethke J M, Merland J J, et al. Ethanol embolization of arteriovenous fistulas: a primary mode of therapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1990;1:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(90)72510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourao G S, Hodes J E, Gobin Y P, Casasco A, Aymard A, Merland J J. Curative treatment of scalp arteriovenous fistulas by direct puncture and embolization with absolute alcohol. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:634–637. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.4.0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F, Rossi P, Odink H. How I do it: arteriovenous malformation management. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:65–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02563895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keljo D J, Yakes W F, Andersen J M, Timmons C F. Recognition and treatment of venous malformations of the rectum. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23:442–446. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199611000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F, Krauth L, Ecklund J, et al. Ethanol endovascular management of brain arteriovenous malformations: initial results. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:1145–1154. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F. In: Castaneda-Zuniga WR, Tadavarthy SM, editor. Diagnosis and management of vascular anomalies. Interventional Radiology. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. pp. 103–138.

- Yakes W F. In: Savader SJ, Trerotola SO, editor. Diagnosis and management of venous malformations. Venous Interventional Radiology with Clinical Perspectives. New York: Thieme; 1996. pp. 139–150.

- O'Donovan J C, Donalson J S, Morello F P, Pensler J M, Vogelzang R L, Bauer B. Symptomatic hemangiomas and venous malformations in infants, children and young adults: treatment with percutaneous injection of sodium tetradecyl sulfate. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:723–729. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.3.9275886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shireman P K, McCarthy W J, Yao J ST, Vogelzang R L. Treatment of venous malformations by direct injection with ethanol. J Vasc Surg. 1997;126:838–844. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang R L, Yakes W F. In: Pearce WH, Yao JST, editor. Vascular malformations: effective treatment with absolute ethanol. Arterial Surgery: Management of Challenging Problems. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange; 1997. pp. 553–560.

- Lee B B, Kim D I, Huh H, et al. New experiences with absolute ethanol sclerotherapy in the management of complex form of congenital venous malformation. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:764–772. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.112209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer B, Burrows P E, Zurakowski D, Mulliken J B. Sclerotherapy of craniofacial venous malformations: complications and results. Plast Reconst Surg. 1999;104:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F. Sclerotherapy of craniofacial venous malformation: complications and results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deLorimier A A. Sclerotherapy for venous malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:188–192. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen P, Wikholm G, Fogdestam I, Naredi S, Eden E. Instillation of alcohol into venous malformations of the head and neck. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1994;28:279–285. doi: 10.3109/02844319409022012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen P A, Wikholm G, Rodriquez M, et al. Orbital lymphatic malformations: direct puncture and sclerotherapy with sotradecal. Intervent Neuroradiol. 2001;7:193–199. doi: 10.1177/159101990100700303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F. In: Mattasi R, Belov S, Loose DA, Vaghi M, editor. Diagnosis and treatment of bone vascular malformations. Malformazioni Vasculari ed Emangiomi. Milan, Italy: Springer-Verlag; 2003. pp. 60–65.

- Yakes W F. In: Mattasi R, Belov S, Loose DA, Vaghi M, editor. Diagnosis and therapy of soft tissue vascular malformations. Malformazioni Vasculari ed Emangiomi. Milan, Italy: Springer-Verlag; 2003. pp. 66–70.

- Lee B B. Congenital venous malformation: changing concept on the current diagnosis and management. Asian J Surg. 1999;22:152–154. [Google Scholar]

- Lee B B. Advanced management of congenital vascular malformations (CVM) Int Angiol. 2002;21:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes W F. Sclerotherapy of craniofacial venous malformations: complications and results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer B, Burrows P E, Zurakowski D, Mulliken J B. Sclerotherapy of craniofacial venous malformations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]