ABSTRACT

Direct percutaneous jejunostomy is considered in patients where percutaneous gastrostomy is not feasible (stomach removed or inaccessible). Percutaneous jejunostomy is more difficult than gastrostomy techniques. Direct jejunostomy is performed under fluoroscopic guidance, using a nasojejunal tube to distend the jejunum. The jejunal loop is punctured using a Cope suture anchor, under ultrasound guidance. Water-soluble contrast material is injected through the needle to document intralumenal position, and an anchor is inserted. With the guide wire in place, the track is dilated and a 10-F pigtail catheter inserted into the proximal jejunum. Fluoroscopy can also be used to aid puncture using dilute contrast material, if used via the nasogastric tube. Antiperistaltic agents can also be used to aid jejunal puncture. The cumulative procedure-related mortality from the three reported series in the literature is 2.4%, with minor complications occurring in 10 to 11%. Although jejunostomy is not performed frequently, this is a feasible procedure for interventional radiology.

Keywords: Percutaneous jejunostomy, jejunal obstruction

Direct percutaneous jejunostomy was first described in a case report by Gray and colleagues in 1987.1During the next 15 years, only three series describing percutaneous jejunostomy2,3,4 were published, whereas there are numerous reports detailing percutaneous gastrostomy. This can probably be explained by the facts that percutaneous jejunostomy is only considered in those cases when percutaneous gastrostomy is not feasible and that percutaneous jejunostomy is a technically more demanding procedure. Although it does seem to have a learning curve, percutaneous jejunostomy has proved to be a relatively safe and feasible technique for long-term feeding in those institutions that have become familiar with it.2,3,4

INDICATIONS

The main indication for percutaneous jejunostomy is prolonged (more than 2 to 4 weeks) enteral feeding in those cases when the stomach has been removed or is inaccessible.2,3,4 This includes patients with malignant or benign obstruction of the digestive tract and especially patients with an obstruction after surgical treatment for carcinoma of the esophagus and cardia. Other indications include leakage from the upper digestive tract following surgery or injury, severe pancreatitis, gastric paralysis, and neurologic disorders. Occasionally, percutaneous jejunostomy is used for decompression of the jejunum in cases of bowel obstruction (Fig. 1) and for recanalization of the biliary tree after a biliodigestive anastomosis.3,4

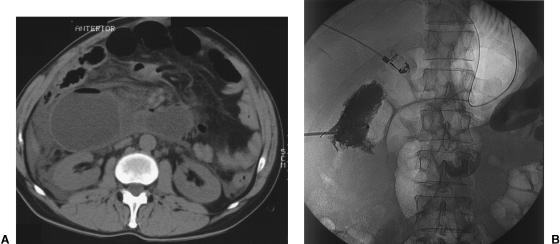

Figure 1.

(A) Decompressing percutaneous jejunostomy in a patient with dilation of the afferent loop of a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Axial CT scan of the upper abdomen shows a dilated small bowel loop in the right upper quadrant. (B) The position of the catheter is confirmed after jejunostomy by injecting contrast material.

Because percutaneous gastrostomy and transgastric jejunostomy are technically easier than percutaneous jejunostomy, these techniques should be considered first for enteral feeding. Percutaneous transgastric jejunostomy is especially useful in those cases when only the proximal part of the stomach has been removed or is overgrown by tumor.

Contraindications to percutaneous jejunostomy are the same as for percutaneous gastrostomy, ascites and uncorrectable bleeding disorders being the two most common absolute contraindications. The problem of overlying colonic loops can sometimes be overcome by bowel decompression for 24 to 48 hours using a rectal cannula.

TECHNIQUE

The patient is fasted for 12 to 24 hours prior to the procedure. See Figure 2. Antibiotics are not administered routinely. Sedation and analgesia are obtained by administering fentanyl 0.05 to 0.1 mg, midazolam 1.25 to 5.0 mg intravenously, and lidocaine 1% locally.

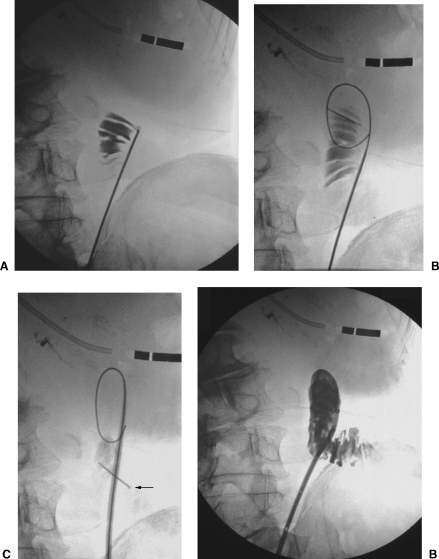

Figure 2.

(A) Percutaneous jejunostomy in a patient with cancer of the esophagus and stomach. The jejunum is punctured; the correct position of the needle is confirmed by injecting a small amount of contrast material. (B) The guide wire is inserted. (C) The catheter and stylet are inserted. The anchor (arrow) is in place. (D) The catheter is in place.

The combination of a vascular catheter (for example 5-F PIER or vertebral catheter, Cordis, Roden, The Netherlands) and a 0.035-inch hydrophilic guide wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) is introduced through the nose into the pharynx and is passed through the upper digestive tract as far into the jejunum as possible using fluoroscopic guidance. Obstructions in the digestive tract are often relatively easy to pass with this technique (Fig. 3).

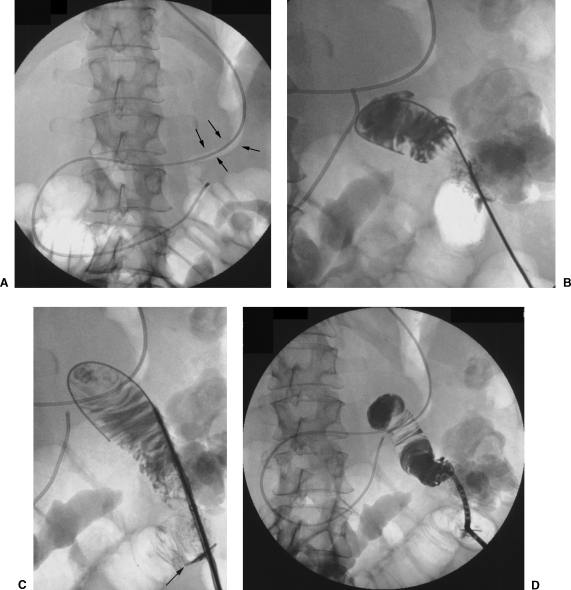

Figure 3.

(A) Percutaneous jejunostomy in a patient with carcinoma of the stomach. Abnormal stomach configuration with narrowing of the lumen and a thickened wall (arrows) at fluoroscopy. A vascular catheter has been passed through the stomach and duodenum into the jejunum. (B) The jejunum has been punctured and a guide wire is introduced into the jejunal lumen after injecting a small amount of contrast material. (C) The catheter, fitted on a stylet, is introduced over the guide wire. Note the position of the anchor (arrow) at the point of entry into the jejunal lumen. (D) The position of the catheter is confirmed with injection of a small amount of contrast material.

The catheter is subsequently flushed with lukewarm water or saline (NaCl 0.9%) to distend the jejunum as much as possible. To enhance ultrasonographic identification of the jejunum, a 0.035-inch Teflon guide wire with a movable core and a floppy end can be introduced through the nasojejunal catheter into the jejunal lumen.

The jejunum is subsequently identified ultrasonographically by its anatomic location in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen, the presence of peristalsis, a fluid-filled lumen, or the inserted guide wire. Colonic loops can usually be distinguished from small bowel by their lateral location in the abdomen and the presence of air and fecal material within the lumen, which is accompanied by acoustic shadowing.

The jejunum is punctured with a 17-gauge needle preloaded with a Cope suture anchor (Cook, Bjaeverskov, Denmark). Puncturing is achieved by slowly advancing the needle against the jejunal wall under ultrasonographic guidance. The wall of the jejunum is penetrated by a firm, short thrust with the needle. The needle is then withdrawn under ultrasonographic guidance until the tip of the needle can be identified within the jejunal lumen. Needle position within the lumen is confirmed fluoroscopically by injecting a small amount of water-soluble contrast material through the needle. The anchor is carefully pushed into the jejunum with a 0.035-inch stiff Teflon Amplatz guide wire. Careful manipulation is necessary to avoid pushing the jejunal loop off the needle. Correct placement of the guide wire (Fig. 4) can usually be recognized fluoroscopically when either its tip follows the contrast material within the jejunal lumen or the guide wire forms a loop within the jejunal lumen.

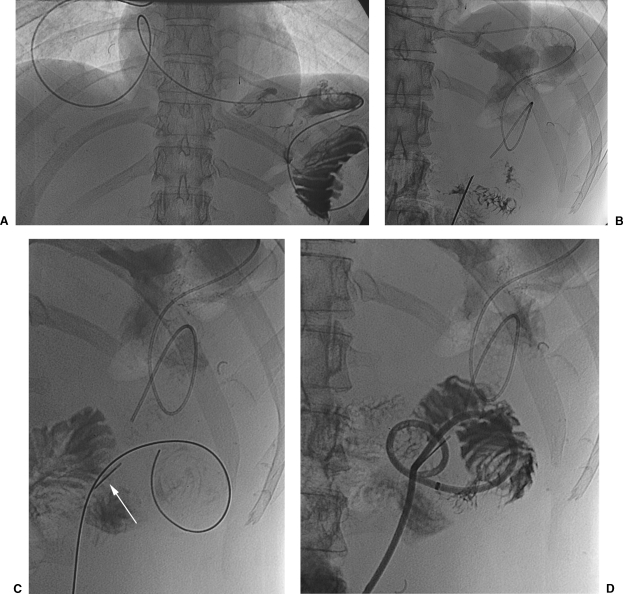

Figure 4.

(A) Percutaneous jejunostomy in a patient who previously underwent resection of the esophagus with pull-up of the stomach and an esophagogastric anastomosis in the neck. A vascular catheter is passed through the upper digestive tract into the jejunum in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen. (B) The jejunum is punctured and the needle position is confirmed. (C) The guide wire and anchor (arrow) are introduced into the lumen. (D) The catheter has been inserted over the guide wire.

When the guide wire is in place, the tract is dilated with a 10-F dilator followed by the insertion of a 10-F pigtail catheter with slip coat hydrophilic coating fitted on a stylet (Cook, Bjaeverskov, Denmark). During dilatation and catheter insertion into the jejunum, variable traction is applied on the suture of the Cope anchor to fix the jenunal loop. Too much traction on the suture must be avoided, especially when passing dilators or the catheter through the abdominal wall, since this may cause the suture to break.

The position of the catheter within the jejunal lumen is confirmed by another injection of contrast material. The catheter is locked and is sutured to the skin together with the Cope anchor (Fig. 5).

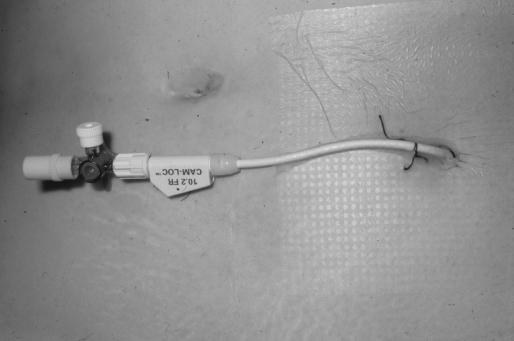

Figure 5.

Jejunostomy catheter in situ and sutured to the skin.

AFTERCARE

During the first 12 to 24 hours, external drainage is applied to the jejunostomy catheter to avoid or limit pericatheter leakage. Catheter function is first tested with the infusion of saline for several hours and if this is tolerated the catheter is subsequently used for feeding. Feeding is postponed or interrupted and external catheter drainage is (re)applied if the patient develops abdominal pain. In addition, the position of the catheter can be confirmed by the injection of contrast material through the catheter under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 6). However, even if the catheter is correctly positioned within the jejunal lumen and there is no leakage of contrast material, feeding should be postponed if there is abdominal pain. After 10 days the suture of the Cope anchor should be cut and the sutures to the skin should be removed. The patient, referring physician, and nurses should be informed that the lumen of a jejunostomy catheter is smaller than that of a percutaneous (endoscopic) gastrostomy catheter. It is therefore more susceptible to occlusion and the administration of crushed tablets should be avoided.

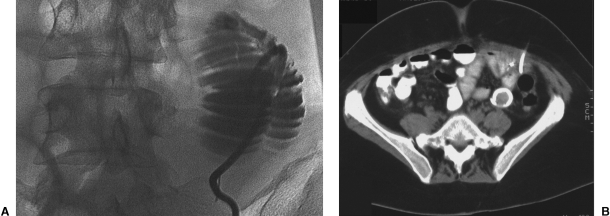

Figure 6.

(A) Fluoroscopic image of a percutaneously inserted jejunostomy catheter. (B) CT image of a percutaneously inserted jejunostomy catheter.

ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES

Some authors use fluoroscopy instead of ultrasound for identifying and puncturing the jejunum. If using fluoroscopy, the colon is opacified with dilute contrast material. In some instances, puncture of the jejunal lumen may be facilitated by the per oral introduction of a balloon catheter, which is subsequently punctured percutaneously.2,3 Intravenous use of glucagon has been advocated to slow peristalsis and dilate the jejunal lumen. However, due to the absence of peristalsis, identification of jejunal loops may be more difficult, especially when repeated punctures are necessary. Hallisey and Pollard recommend puncture of the jejunum at the antimesenteric side to avoid vascular injury and to use multiple anchors to fixate the jejunum.2 In our experience, it is very difficult to determine the exact location of the mesentery either ultrasonographically or fluoroscopically. Therefore, we recommend puncture of the jejunum where it is best seen and the introduction of only one anchor. With careful dilatation, one anchor seems to provide enough fixation of the jejunum against the abdominal wall to allow dilatation and catheter insertion.

RESULTS IN THE LITERATURE

Reported results of percutaneous jejunostomy from the three published series are rather similar, with technical success rates ranging from 85 to 95%. Reasons for failure1 are difficulty in puncturing the jejunum due to mobility or collapse of its lumen in patients with a more proximal obstruction of the digestive tract,2 and difficulty in maintaining position within the jejunal lumen once it has been punctured, because dislodgment can occur during anchor or catheter insertion.

The most important complication of percutaneous jejunostomy is intraperitoneal leakage, which can cause peritonitis and death. Intraperitoneal leakage may be caused by catheter malposition or early dislodgment, but may also be caused by pericatheter leakage. The cumulative procedure-related mortality for the three series is 2.4% (2 of 82 patients).2,3,4

Minor complications are encountered in 10 to 11%. A relatively common complication is inflammation of the skin around the catheter, which can generally be treated by removing the skin sutures and other conservative local measures. Once in place, a jejunostomy catheter can function properly for several months to more than 1 year.4

NONRADIOLOGICAL JEJUNOSTOMY

Surgical jejunostomy is an alternative to percutaneous jejunostomy but is associated with much higher major (18%) and general (52 to 72%) complication rates. In addition this technique is associated with other disadvantages such as need for general anesthesia, postoperative ileus and wound infection.5,6,7

Laparoscopic jejunostomy is also more invasive for the patient, requires general anesthesia, and can be complicated by trocar injuries and peritonitis.8,9

Percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy is technically more difficult and is limited to those patients in whom the pharynx, esophagus, and stomach can be passed by an endoscope. This excludes a significant number of patients in whom a jejunal feeding tube is indicated.10

CONCLUSION

Percutaneous jejunostomy is a feasible technique with an acceptable complication rate that should be considered in patients requiring long-term enteral feeding and in whom the stomach is not accessible.

REFERENCES

- Gray R R, Ho C S, Yee A, Montanera W, Jones D P. Direct percutaneous jejunostomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:931–932. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.5.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallisey M J, Pollard J C. Direct percutaneous jejunostomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1994;5:625–632. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(94)71567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope C, Davis A G, Baum R A, Haskal Z J, Soulen M C, Shlansky-Goldberg R D. Direct percutaneous jejunostomy: techniques and applications—ten year experience. Radiology. 1998;209:747–754. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.3.9844669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overhagen H van, Ludviksson M A, Laméris J S, et al. US and fluoroscopic-guided percutaneous jejunostomy: experience in 49 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:101–106. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M B, Seabrook G R, Quebbeman E A, Condon R E. Jejunostomy: a rarely indicated procedure. Arch Surg. 1986;121:236–238. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400020122016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom L R, Larson D E, Zinsmeister A R, Sarr M G, Silverstein M D. Utilization and outcomes of surgical gastrostomies and jejunostomies in an era of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a population based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:829–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltz C R, Morris J B, Mullen J L. Surgical jejunostomy in aspiration risk patients. Ann Surg. 1992;215:140–145. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199202000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrink M H, Foster J, Rosemurgy A S, Carey L C. Laparoscopic feeding jejunostomy: also a simple technique. Surg Endosc. 1992;6:259–260. doi: 10.1007/BF02498817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J B, Mullen J L, Yu J C, Rosato E F. Laparoscopic-guided jejunostomy. Surgery. 1992;112:96–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard T J, Bloom A D. A technique of direct percutaneous jejunostomy tube placement. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:173–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]