ABSTRACT

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) is a useful functional imaging method that complements conventional anatomic imaging modalities for screening patients with colorectal hepatic metastases and hepatocellular cancer to determine their suitability for interventional procedures. FDG PET is more sensitive in detecting colorectal cancer than hepatocellular cancer (~90% versus ~50%). The likelihood of detecting hepatic malignancy with FDG PET rapidly diminishes for lesions smaller than 1 cm. The greatest value of FDG PET in these patients is in excluding extrahepatic disease that might lead to early recurrence after interventional therapy. Promising results have been reported with FDG PET that may show residual (local) or recurrent disease before conventional imaging methods in patients receiving interventional therapy. For patients with colorectal hepatic metastases, many investigators believe that patients with PET evidence of recurrent hepatic disease should receive additional treatment even when there is no confirmatory evidence present on other methodologies. For patients with hepatocellular cancer no conclusions regarding the value of FDG PET for assessment of response to interventional therapy can be reached as there is almost no published data.

Keywords: PET, FDG, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular cancer

With the rapid technical advancements in radiological imaging, identifying both primary and metastatic liver tumors is increasingly common. Metastatic tumor to the liver is far more common than primary hepatic neoplasms (hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma). Common sites of metastatic tumor to the liver include colon, stomach, pancreas, breast, and lung. Hepatic metastasis from gastrointestinal neoplasms is frequent due to hematogenous spread via the portal vein. Until recently, therapeutic options for malignant liver lesions consisted mainly of systemic chemotherapy and less commonly surgical resection or transplantation. Recently newer tumor ablation regimens (cryotherapy, radiofrequency, and intrahepatic embolization) are proving to be effective alternative treatments in selected patients. Accurate staging of primary and metastatic hepatic tumor is essential to determine appropriate modalities of treatment and subsequent tumor response. The presence of extrahepatic disease makes it less likely that therapy limited to the liver will result in a sustained therapeutic response. In addition, inadequate treatment of liver neoplasms will lead to an early recurrence of tumor.

Conventional radiological methods of staging hepatic malignancy include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR), and ultrasound. Positron emission tomography (PET) is now more frequently being used to evaluate liver malignancy because of its increasing availability and improved third-party reimbursement. Recent technical improvements combine multidetector CT scanners in-line with PET cameras (PET/CT). PET is now a widely accepted form of imaging that aids in the whole body staging and restaging of specific types of malignancy including colorectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, melanoma, and other malignancies that frequently metastasize to the liver. Hepatocellular cancer has also been studied with PET imaging but information concerning the usefulness of PET for cholangiocarcinomas is more limited.

Tumor imaging with PET depends on functional localization of the radiopharmaceutical and is therefore different from other radiographic methods that characterize tumor size and/or vascularity. Colorectal cancer is the most common metastatic lesion to the liver for which PET imaging is likely to be used to obtain additional staging information prior to interventional therapy. Many published reports attempt to determine whether resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer is beneficial. Expectations regarding the likelihood of benefit from an interventional radiological procedure would be similar when the disease is limited to the region that is to be treated. The role of PET imaging for hepatocellular cancer is less certain because reports indicate greater variability in tumor detection rates. PET has also been proposed as a method to evaluate therapeutic response because functional measurements may be altered before anatomic changes can be detected.

BACKGROUND

PET is different from other imaging modalities due to the use of radiopharmaceuticals whose accumulation is due to specific cellular mechanisms that characterize properties related to tumor activity. There are PET radiopharmaceuticals that evaluate tumor blood flow, glucose metabolism, protein synthesis, proliferation, apoptosis, hypoxia, and the presence of specific receptors.

The most widely available PET radiopharmaceutical is 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), a glucose analog that accumulates in regions of hypermetabolic activity. The radiotracer, fluorine-18, is cyclotron-produced and has a 110-minute half-life. This relatively long decay rate allows for distant regional distribution of 18F-FDG following automated synthesis at centrally located cyclotrons. The positron-electron interaction of the 18F resulting in the characteristic emission of two 511-keV photons ~180 degrees apart occurs within a very short range (4 mm) of FDG localization. This minimizes the distance between the origin of the positron emission and the actual location of the detected event. The entry of FDG into cells is largely a one-way process with little subsequent cell washout. After the enzyme hexokinase converts FDG into a phosphorylated form, the tracer is unable to be further metabolized through the glycolytic pathway. FDG is unlikely to be dephosphorylated (thus allowing for possible exit from the cell) due to the low levels of the necessary enzyme intracellular glucose-6-phosphatase in most tumor cells. Bos et al found that increased FDG uptake in breast cancer cells correlated with the increased expression of Glut-1 (a cell surface transporter), the mitotic activity index, the amount of necrosis, the number of tumor cells/volume, the expression of hexokinase, number of lymphocytes, and microvessel density.1 Overexpression of glucose cell surface transporter, typically Glut-1 and less often Glut-4, is a common feature of many tumor types. In general, the more aggressive biological characteristics that a tumor exhibits, the more likely there will be FDG uptake.

PATIENT PREPARATION AND IMAGING

Blood glucose levels should not be elevated before an FDG injection because this will result in less intracellular uptake of FDG due to competition from this source. Poorer detection of tumor activity may occur in patients with blood glucose levels greater than 150 mg/mL; patients with blood glucose levels greater than 200 mg/mL should not be injected with FDG. Diabetic patients need to be well controlled prior to undergoing an FDG study.

Clinical tumor imaging with FDG PET is done after the intravenous injection of 8 to 15 mCi of FDG. For torso whole body imaging (base of skull to the midthigh level), PET data are acquired for 3 to 5 minutes at each table position usually requiring five to seven slightly overlapping regions. Typical whole body scans require ~30 minutes to complete. Shorter whole body acquisitions (taking as little as 10 minutes) may be possible with new higher-sensitivity PET systems using three-dimensional data acquisition and advanced reconstruction algorithms. Acquisition of attenuation data, which is important for quantification of uptake, may take an additional 3 minutes per table position (15 to 20 minutes) using an older PET system but less than 1 minute total for all table positions using an in-line PET/CT scanner. Standard acquisition protocols require 1 hour between tracer injection and imaging during which time the patient remains in a quiet environment. Delaying FDG PET imaging for greater than 1 hour may improve lesion detectability because tumor uptake may continue to rise while background activity diminishes during this time. However, improved tumor detectability is limited by the physical decay of the 18F (~30% each half hour). A delay greater than 90 to 120 minutes before imaging is not practical.

PET/CT

When PET/CT scanners were first introduced, there was significant concern that intravenous (IV) and oral contrast administration would have a detrimental effect on the algorithm used to convert CT Hounsfield units into appropriate attenuation values for PET imaging correction. Overcorrection of image data due to high attenuation from contrast may result in false-positive PET findings. Correlation with corresponding axial CT images allows correct interpretation. It is usually obvious when intraluminal contrast results in an artifactual increase in PET tracer distribution. Artifactually increased PET activity may be seen in the subclavian vein following a bolus IV contrast injection due to overcorrection, but a similar effect is unlikely in the abdomen secondary to systemic contrast dilution. Use of IV contrast protocols for PET/CT is still actively debated. Although IV contrast-enhanced CT imaging with breath holding improves detection of small lesions (especially liver lesions) likely to be missed on PET images, it also increases the likelihood of misregistration with PET images. Oral contrast does not usually present a problem when using dilute oral contrast preparations, although at times overcorrection will be seen in the bowel, most typically in the ascending portion of the colon.2

IMAGE INTERPRETATION

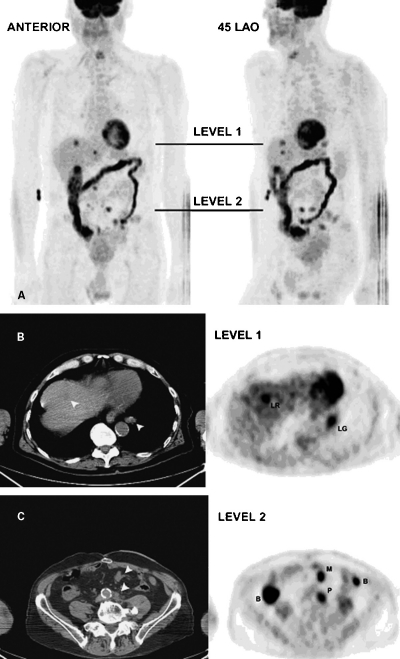

The sensitivity of PET imaging for detecting lesions is very high in tumors that have a high avidity for FDG. Using current PET cameras lesions as small as 6 mm can be visualized. However, detection of liver lesions is not as sensitive, being limited to ~1 cm or greater due to substantial normal background activity. In addition, small or subtle areas of increased uptake in the liver can be obscured due to respiratory motion. Due to normal variable FDG activity of the bowel, discriminating abnormal areas of tumor uptake can be problematic. PET/CT improves overall accuracy by identifying sites of increased FDG uptake to corresponding areas of bowel on CT images. The unpredictable normal activity often found in the esophagus (particularly the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction), stomach, and colon can be confirmed by correlation with the corresponding CT images. Fig. 1 shows a patient with colorectal cancer and liver, mesentery, retroperitoneal, and lung metastases, who exhibits marked increased large bowel uptake. Normal and variable uptake of FDG also occurs in the genitourinary collecting system. False-positive interpretations of abnormal FDG activity can be reduced or avoided with the administration of IV fluids and furosemide. Comparing CT data to corresponding PET images during combined PET/CT examination usually allows for accurate discrimination of physiological from pathological FDG activity. PET/CT also can reduce false-negative interpretations in the abdomen. For example, subtly increased FDG uptake in a periaortic location is more likely to be identified as suspicious for tumor when it maps directly onto a lymph node as seen on the CT scan.

Figure 1.

(A) Volume-rendered PET images from a patient with a history of recurrent colorectal cancer 3 years following surgical resection of a solitary liver metastasis. Anterior and 45-degree left anterior oblique projections show marked but normal uptake in the large bowel. Abnormal foci of increased FDG uptake in the liver, mesentery, retroperitoneal, and lung are metastases. Black lines indicate the transaxial levels for subsequent figures (level 1 for Fig. 1B; level 2 for Fig. 1C). (B) Non-contrast-registered CT and corresponding PET images obtained at level 1 as seen in Fig. 1A. Metastases are seen in the liver (LR) and lung (LG) on the PET images. Arrowheads indicate matching regions on the CT images. (C) Non-contrast registered CT and corresponding PET images obtained at level 2 as seen in Fig. 1A. Metastases are seen in the mesentery (M) and periaortic region (P) on the PET images. Arrowheads indicate matching regions on the CT images. Two areas of normal bowel uptake (B) are seen on the PET image. Bowel uptake on the right is easily characterized as ascending colon activity but bowel uptake on the left is hard to distinguish from the mesenteric metastasis without reference to corresponding CT slices above and below this level.

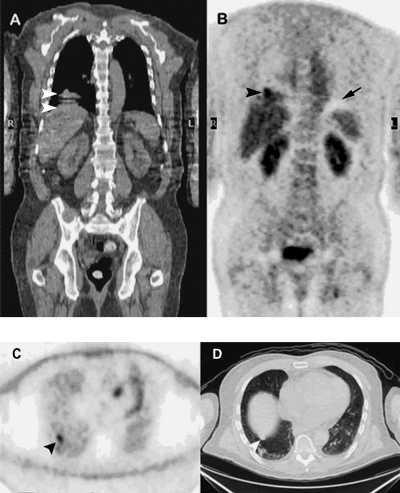

Partial volume effects on the PET images due to respiratory motion reduce lesion conspicuity. Because PET images require a long acquisition interval (2 to 5 minutes, multiple breaths), an abnormal focus identified on PET images reflects an average position over the entire respiratory cycle. The subsequent blurring of the abnormal focus over a larger geographic region introduced by motion also reduces contrast between normal and abnormal tissue. Although there is also some blurring due to respiratory motion during CT imaging of the chest and upper abdomen, the degree is minor compared with the PET scan, because the CT images are obtained over a shorter interval (seconds, total length less than a respiratory cycle). Sometimes the averaged position on PET is greatly different from the more instantaneous position on CT scan and misregistration of the fused images ensues. Because there is significant respiratory motion at the level of the right lung base and dome of the liver, the location of an abnormal focus of FDG uptake in the liver in this region can sometimes appear to be in the lung or vice versa (Fig. 2). In this situation, it may be easier to determine the location of the lesion by examining the non-attenuation-corrected images.

Figure 2.

Registered coronal CT (A) and attenuation-corrected coronal PET (B) images. CT images were acquired during normal quiet breathing. This usually (but not always) results in better registration with PET images, which take several breaths and minutes to acquire. White arrowheads on the coronal CT image show a misplaced dome of the liver due to capture of several positions resulting from respiratory excursion during CT acquisition. The black arrowhead on the coronal PET image points to a lung metastasis that appears to be within the dome of the liver due to overcorrection from mispositioned CT data. Small black arrow on the PET image points to a photopenic region that is an artifact due to variable attenuation from diaphragmatic respiratory excursion during the PET acquisition. Non-attenuation-corrected PET (C) and CT (D) transaxial images at level indicated by black arrowhead on Fig. 2B. In non-attenuation-corrected PET images, normal lung activity appears increased compared with adjacent regions because there is less attenuation of incident radioactivity through this region (primarily air) than through surrounding denser tissue structures. The black arrowhead in Fig. 2C points to focal FDG uptake due to a metastasis within the lung parenchyma. The white arrowhead in Fig. 2D points to a nodule in the lung that is very close to the dome of the liver.

QUANTIFICATION

Interpretation of PET images is usually performed qualitatively by visually assessing the tumor-to-background ratio. When serial studies are available, lesion comparison with either quantitative or semiquantitative techniques may be helpful. Research protocols sometimes utilize dynamic imaging of FDG accumulation within a specific tumor site during the first 30 minutes after injection to characterize compartmental rates. Accurate kinetic modeling requires the additional assessment of arterial radiotracer activity, which can be determined by blood sampling or indirectly by assessing changes in a representative vascular region on the PET images. This type of assessment is difficult to perform routinely and is more susceptible to precision errors than a semiquantitative approach. The most commonly used semiquantitative measurement is the standardized uptake value (SUV) corrected for body weight. For obese patients, values standardized for lean body mass may be more useful. SUVbw is defined as:

|

If the body is assumed to be largely composed of water, then 1 g of body weight is ~1 mL, and the SUV becomes unitless. After injection, if FDG was immediately and uniformly distributed throughout the body, SUVbw would equal 1. Because patients are typically injected in a fasting state, and little FDG goes to fat or muscle, the SUV in these regions will be low. SUV in the liver after FDG injection is always elevated compared with other organs due to its relatively greater metabolic state. The presence of more FDG activity in the liver and vascular structures (due to intravenous injection) results in SUVs that are greater than 1 in these structures. Similarly, metabolically active tumor will typically have elevated SUV levels, often greater than 3. Tumor SUVs diminish when therapy is effective. Comparison of values from different studies should be interpreted with caution due to several factors: the SUV can be affected by changes in blood glucose levels and body weight, differences in injection time and image acquisition, the amount of tracer extravasation during injection, the region of interest selected, and finally the spatial resolution (partial volume effect) of the PET system used.3

Information obtained from kinetic modeling (based on dynamic imaging) during FDG PET imaging may be more accurate for predicting early response to therapy than static SUV measurements. Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss et al used FDG PET to gauge the response of colorectal liver metastases to second-line chemotherapy with the 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) regimen.4 They found that SUV measurements after four cycles (3 months after the start) of therapy were less accurate (69% correct) in classifying patients into the longer survival group than were methods based on a combination of kinetic parameters (FDG PET activity at baseline versus that at completion of the first cycle [72%] and baseline activity versus that at completion of the fourth cycle of chemotherapy [79%]).

COLORECTAL CANCER

Liver metastases are present in 25 to 30% of patients with colorectal cancer at the time of presentation. The liver is usually the first site of metastasis unless the primary tumor is located in the distal third of the rectum. Another 25% of patients develop liver metastases in the future despite resection of their primary tumor. If metastatic disease is limited to the liver some patients may benefit from hepatic resection or other local therapy. Patients with unresectable liver metastases have a median survival of less than 1 year. In a review of the published literature Truant et al found that up to 40% of patients felt to be resectable by CT criteria (liver metastases only) at surgery had extrahepatic metastases.5 In addition, 40% of patients thought to have undergone curable resections were found to have recurrent disease (hepatic or extrahepatic) within 1 year.

Factors related to a good prognosis following localized treatment of hepatic metastases include the completeness of tumor removal and the pathological characteristics of the tumor. The findings on PET appear to correlate well with surgical findings. Strasburg et al found that 95% of patients with colorectal cancer who had limited disease found on PET (no extrahepatic metastases) had resectable disease at laparotomy.6 Fernandez et al retrospectively studied the 5-year survival in 100 patients who underwent hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer after screening with FDG PET.7 Overall survival after hepatic resection for these patients was 85.7% at 1 year, 66.0% at 3 years, and 58.6% at 5 years. FDG PET appears to be more accurate then conventional imaging modalities in detecting patients without extrahepatic metastases who may benefit from interventional therapy. In patients screened with PET where there is presumably better detection of extrahepatic metastases, the primary tumor grade (well versus poorly differentiated) becomes a more important predictor of survival relative to factors such as the presence of multiple hepatic metastases, lesion size (≥ 5 cm), and synchronicity (hepatic metastasis found before or within 1 year of resection of the primary colon cancer). This is because micrometastatic disease is more likely to occur with poorly differentiated colon cancer below the threshold of detectability by FDG PET.

Two meta-analyses have been published examining the sensitivity of FDG PET for detection of colorectal cancer. Kinkel et al reviewed studies for hepatic metastasis using PET, ultrasonography, CT, and MR between 1985 and 2000.8 Although patients with colorectal, gastric, and esophageal cancers were grouped together to achieve a larger cohort of patients, the location of the primary tumor did not affect the sensitivity of the imaging modality. The sensitivity for PET was 90%, MR 71%, CT 70%, and ultrasonography 66%. The meta-analysis performed by Huebner et al for reports between 1990 and 1999 found whole body FDG PET had an overall sensitivity for detecting recurrent colorectal cancer of 97%, a specificity of 76%, and changed the management in 29% of patients for whom therapeutic decision making was tracked.9

More recent studies (since 1999) show slightly different results particularly in regarding the impact of PET on patient management. A retrospective study by Lonneux et al found that staging was correctly modified by PET in 41% of patients studied for recurrent colorectal disease.10 Detection of recurrent disease was better with PET than CT (82% versus 68%). A prospective study by Kalff et al evaluated the clinical impact of FDG PET in patients with recurrent colon cancer, excluding those who had confirmed lesions found by conventional imaging.11 Management was changed by PET in 59% of all patients and 65% of patients with a rising carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level. Aggressive local therapy was abandoned in 60% of the patients. Prospective data reported by Truant et al is less encouraging as FDG PET changed therapeutic management correctly in only 9% and incorrectly in 6%.5

The sensitivity for detection of colorectal cancer with PET varies depending on tumor histology with poorer results found in patients with mucinous adenocarcinomas. Whiteford et al report the sensitivity of FDG PET for detection of mucinous adenocarcinoma to be 58% (16 patients) compared with 92% in patients with nonmucinous tumors (93 patients).12 This may be due to the relative hypocellularity of mucinous lesions relative to their size.

In patients with colorectal cancer there is general agreement that FDG PET imaging is useful for detection of extrahepatic disease, but there is conflicting data regarding its value in detecting hepatic metastases. Intraoperative ultrasound plays an important role in detecting and guiding resectability of hepatic tumors. Rohren et al evaluated FDG PET for detection of hepatic metastases due to colorectal cancer using intraoperative ultrasound as the gold standard and found 79% sensitivity and 62% specificity.13 The average size of metastases detected with PET was 3.2 cm; lesions not detected with PET had an average size of 1.6 cm. Statistical modeling of this data predicted that only 40% of 1-cm lesions would be detected with PET. In 2002 Rydzewski et al compared the sensitivity of intraoperative ultrasound, FDG PET, and the combined results of CT and MR with surgical pathological findings.14 PET and intraoperative ultrasound had similar sensitivities of ~71%, and grouped CT and MR imaging had a sensitivity of 55%. Positive predictive value for an individual lesion was 93% for PET, 89% for intraoperative ultrasound, and 78% for grouped CT and MR.

Improved disease detection will probably be seen with multidetector CT (MDCT) and combined PET/inline MDCT scanners (PET/CT). A study by Numminen et al found that preoperative MDCT detected 96% and MR imaging, 78% of focal liver lesions found by intraoperative ultrasound and palpation.15 Selzner et al evaluated the diagnostic value of PET/CT (nonenhanced) with contrast-enhanced MDCT in 76 patients, basing their comparison on surgical findings and 3- to 6-month follow-up.16 The sensitivity for detection of intrahepatic metastases was 95% for MDCT and 91% for PET/CT, but PET/CT was superior to MDCT for detecting hepatic recurrence after hepatectomy. The overall sensitivity for detection of extrahepatic metastases in untreated patients was 89% for PET/CT and 64% for MDCT. PET/CT was better at detecting specific sites of disease including local recurrence at the primary tumor site (93% versus 53%), metastatic portal and para-aortic lymph nodes (77% versus 54%), lung (100% versus 78%), and bone (75% versus 50%). Chemotherapy within 1 month of the PET/CT scan decreased test sensitivity for local recurrence (66%), hepatic metastases (72%), and extrahepatic metastases (66%). PET/CT resulted in a change in management in 20% of the patients.

HEPATOCELLULAR CANCER

The most frequent type of primary liver tumor, hepatocellular cancer (HCC), is believed to result from a stepwise series of events that begins in a cirrhotic liver. Regenerating nodules, which initially have low-grade dysplastic features, differentiate into high-grade dysplastic nodules and subsequently into small foci of HCC. These tumors do not become clinically apparent until they are fairly large because of extensive preexisting parenchymal liver disease.17 In the late stages of HCC, extrahepatic metastatic disease is frequently found in the lung, lymph nodes, and bone. Prior to the widespread availability of PET imaging, gallium-67 and bone scintigraphy were used to evaluate for extrahepatic disease. Although HCC is usually gallium avid, elevated background activity from gallium in the liver makes it difficult to distinguish tumor from normal tissue. This and other limitations associated with Ga-67 imaging in HCC led to the investigation of PET imaging as an alternative.

FDG PET dynamic imaging with kinetic modeling is reported by Okazumi et al to be of value in differentiating benign liver lesions from HCC.18 In their compartmental modeling of FDG uptake, they found that an increased k3 rate constant (reflecting phosphorylation by hexokinase, the enzyme that metabolizes FDG through the first step of the glycolytic pathway) and a decreased k4 rate constant (reflecting glucose-6-phosphatase activity or the rate of back diffusion) in a specific tumor site increased the likelihood of detecting FDG on subsequent static imaging. The k4 rate constant decreased the more undifferentiated the cell histology, making it more likely that poorly differentiated HCC would have a net accumulation of FDG. The k3 rate constant appeared to decrease with effective therapy resulting in less net accumulation of FDG. Only 57% of HCC patients in this series showed net accumulation of FDG.

The use of less readily available agents labeled with shorter half-life positron-emitting radionuclides, such as those labeled with 11C (20-minute half-life), have contributed to the understanding of the mechanisms of HCC FDG uptake. Ho et al studied 11C-acetate imaging in 39 patients with HCC and compared it with FDG PET imaging.19 The primary localization mechanism for 11C-acetate uptake is believed to be incorporation into fatty acids as they are produced by the tumor. The sensitivity of FDG PET imaging was only 47%, and that of 11C-acetate imaging was 87%. No 11C-acetate uptake was seen in 16 patients with non-HCC hepatic malignancies, all of which showed FDG uptake. Increased uptake of both 11C-acetate and FDG was seen in 34% of the patients with HCC. Well-differentiated HCC was more likely to be detected with 11C-acetate, whereas poorly differentiated HCC was better visualized with FDG. The use of 11C-acetate is promising for detection of HCC and other malignancies but it is not currently commercially available.

Dynamic imaging and kinetic modeling of FDG PET is not typically used to study HCC because it is a more cumbersome procedure and is limited to imaging only one table position (or region). Khan et al used a simpler method for evaluating HCC patients with FDG PET, visually grading uptake in the region of apparent tumor relative to liver uptake in other areas.20 The mean diameter of HCC lesions evaluated was 5.7 cm. Tumor uptake was greater than liver uptake in 55% of the patients, and CT scans were positive in 90% of patients. However, FDG PET revealed extrahepatic metastases in 3 of 20 patients not seen on abdominal CT scans. Significant differences in uptake were noted between less-differentiated and more-differentiated forms of HCC, but no relation was apparent between serum α-fetoprotein levels (AFP) and FDG uptake. Wudel et al retrospectively studied 91 patients with HCC using FDG PET and found a sensitivity of 64%.21 AFP levels prior to scanning did not predict which FDG PET scans would be positive. HCC lesions with fibrous stroma were more likely to be FDG-positive, but this pathological finding does not significantly correlate with a higher tumor grade. In this study only individuals with a positive baseline FDG PET scan had follow-up FDG PET scans. In this subset of patients the FDG PET scan changed clinical management in 30% (20 patients) largely by monitoring response to treatment (12 patients), detection of distant metastases (five patients), and lastly detecting HCC recurrence (two patients).

The semiquantitative SUV measurement of FDG uptake has been reported to be of limited value in discriminating HCC from native tissue because of the variable degree of FDG uptake of tumor as compared with normal physiological uptake of FDG by the liver. However, Shiomi et al studied whether the SUV obtained from FDG PET imaging correlated with tumor doubling time in patients with HCC.22 The average SUV was calculated from regions of interest placed over the area of maximum uptake in the HCC lesion and in a non–tumor control region of the liver. Tumor SUV alone did not correlate with doubling time but the ratio of tumor SUV to non–tumor SUV did. Patients with an SUV ratio ≤ 1.5 had significantly better survival than the group with an SUV ratio > 1.5. Lee et al also studied the relationship between SUV, the SUV ratio, and tumor pathological grading, in addition to an analysis of gene expression in 10 patients with HCC.23 They reported greater FDG uptake in higher-grade tumors and in those with microarray clustering, a finding of gene expression and repression consistent with higher tumor grading. In particular these patterns of gene expression are related to tumor cell adhesion, invasion, metastasis, and antitumoral immunity and other genes are repressed, such as those associated with regulation of the mitotic spindle assembly.

Only a limited number of patient series have reported a role for FDG PET imaging patients with HCC extrahepatic metastases. This is possibly because they usually appear late in the course of disease and are unlikely to effect survival. Knowledge of extrahepatic metastases may alter the initial plan of treating a patient's primary HCC aggressively. In a series studying the outcome of HCC patients based on different treatment strategies, Rose et al recommend FDG PET in selected patients to exclude extrahepatic metastases, but their supporting data are weak because of the evaluation of only a small number of patients.24 Out of 117 patients presented, 13 of the 23 patients imaged with FDG PET had positive primary tumors, and only 4 of those 13 had evidence of extrahepatic disease. Sugiyama et al evaluated the sensitivity of FDG PET imaging in two groups of patients.25 One group consisted of 14 patients with 37 extrahepatic metastases suspected on the basis of a conventional diagnostic imaging; a smaller second group included five patients with negative imaging but elevated tumor marker levels (AFP and/or des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin). In the first group the detection rate of FDG PET was 83% for extrahepatic lesions greater than 1 cm but only 13% for lesions less than 1 cm. No extrahepatic disease was found by FDG PET in the second group, and overall there were no false-positive lesions. On a per patient basis FDG PET had 79% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and 84% accuracy. There were an equal number of bone metastases that were missed by both FDG PET and bone scintigraphy. In the 14-month follow-up period, patients in the PET-negative group showed no evidence of extrahepatic disease. Although extrahepatic disease was not detected in patients with rising serum tumor markers despite negative PET scans, intrahepatic disease was found by conventional imaging within 1 to 4 months.

RESPONSE TO THERAPY

In patients who have had local treatment of their hepatic malignancy, the most influential factor in predicting clinical outcome is whether there are remaining malignant cells at the margin of the tumor after the intervention. Ruers and Bleichrodt retrospectively reviewed six large studies in which patients underwent hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases.26 They reported that hepatic resection is ineffective at changing survival if hepatic metastases are not completely resected. Positive margins result in near zero survival at 5 years, less than 1-cm disease-free margin ~25% at 5 years, and greater than 1-cm disease-free margin ~42% at 5 years. The total number of metastatic sites at presentation is less important, as long as all lesions are completely resected. Similar data are not available for HCC, but survival is thought to be improved in patients whose tumor volume can be decreased by an interventional approach (chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, surgery, etc.). It is important to note that there are few false-positive FDG PET findings in patients being evaluated for liver malignancy. In some situations, FDG PET may be complementary to MDCT and/or MR imaging in determining that lesion margins are free of tumor.

Several investigators feel that interpretation of PET after local therapy can be complicated because transient and reversible cell damage can cause the negative predictive value to be less than the positive predictive value.27,28 The pattern of FDG uptake is dependent upon the type of treatment and the time interval since it was last delivered. Regenerating liver tissue can show FDG uptake and typically takes several days to evolve. After therapy, significant FDG uptake may be seen in granulation tissue and sites of inflammation caused by recent surgical procedures, such as biopsies and placement of drainage devices. Increased extrahepatic FDG uptake related to radiation therapy for colorectal cancer has been observed but this phenomenon has not been well studied for hepatic malignancies. Radiation-induced FDG uptake is less likely to be seen 6 months following radiation therapy than 3 months based on prior studies on patients with colorectal cancer. Although decreases in FDG uptake due to effective therapy may be seen quickly after chemotherapy (depending on the tumor histology), restaging of tumor burden is generally not recommended until 6 to 8 weeks (or more) after initiation of therapy, or before starting the third treatment cycle.

There are only a limited number of smaller studies that have utilized FDG PET to assess the therapeutic response of the primary or metastatic liver tumors following surgical or other interventional procedures. Antoch et al compared ultrasound, CT, and MR imaging with FDG PET in pigs immediately following radiofrequency ablation.29 Despite the absence of tumor, ultrasound, CT, and MR imaging showed expected hypoechoic/hypodense/hypointense characteristics with enhancement around the necrotic zone (after intravenous contrast administration) immediately following tissue ablation. Because residual or recurrent tumor can have a similar appearance using these modalities in humans, differentiating changes following tumor ablation can be difficult. Serial scanning with CT or MR imaging improves detection of recurrent tumor, but it may take several weeks for physiological contrast enhancement to diminish following ablative injury. There were no similar focal or peripheral rimlike increases in FDG uptake when PET imaging was performed after the ablative procedure in the pig model. This data supports the use of FDG PET immediately following radiofrequency ablation to detect residual disease. On these postprocedural PET studies, higher contrast between the abnormal FDG activity in marginal tumor and the adjacent photopenic zone caused by tissue necrosis (from the interventional procedure) may even improve lesion detection.

FDG PET FOLLOWING INTERVENTIONAL TREATMENT OF COLORECTAL HEPATIC METASTASES

Vitola et al studied the change in FDG PET uptake in 34 hepatic lesions in four patients following tumor chemoembolization.30 In the follow-up FDG PET study obtained 2 to 3 months after treatment, 25 of the 34 lesions showed reduced FDG uptake. Increased FDG activity in six of the patients led to further interventional therapy.

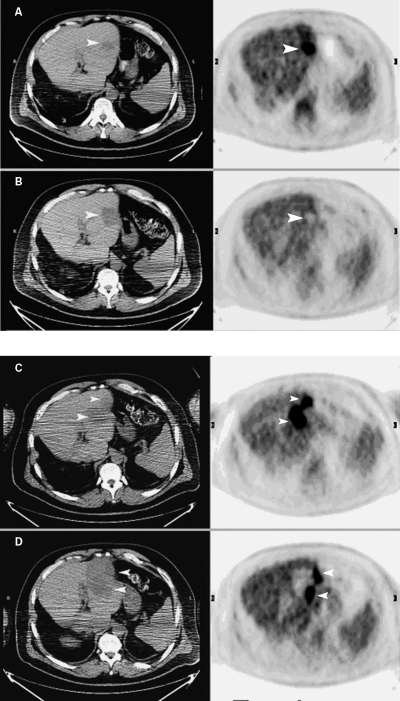

Langenhoff et al evaluated 22 patients with nonresectable metastatic liver disease with FDG PET and CT within 3 weeks of either cryosurgical or radiofrequency ablation, at 6 weeks, and thereafter every 3 months.31 PET was positive in 5 of the 22 patients at the edge of the treated area with one false-positive. None of the FDG-negative lesions showed subsequent local recurrence. In 11 patients new sites of disease within the liver were positive on PET before CT (8.1 versus 11.7 months). Extrahepatic metastases were detected on PET before CT in nine patients (8.4 versus 9.8 months). PET was also more sensitive than CEA levels for the detection of disease in these patients. The authors recommend further local ablative treatment if an early PET scan is positive. Similar findings were reported by Blokhuis et al who studied 15 patients with FDG PET after radiofrequency ablation.32 Both PET and CT identified all disease recurrences; however, FDG PET identified disease sooner (6.8 versus 9.8 months). Earlier disease detection with PET was also reported by Anderson et al who retrospectively reviewed the results of patients who were evaluated for metastatic colon cancer ~9 months after radiofrequency ablation.33 FDG PET demonstrated recurrent disease in previously treated regions in four of eight patients before anatomic studies (CT or MR) became abnormal. Fig. 3 shows PET/CT images from a patient with colorectal hepatic metastases who was treated with radiofrequency ablation initially with good results but had recurrent disease 9 months later.

Figure 3.

PET/CT images were obtained before radiofrequency ablation (A) in a patient with a solitary liver metastasis due to colorectal cancer and 2 months later (B) after radiofrequency ablation. In images obtained before radiofrequency ablation (A), an arrowhead points to the low-attenuation region on the noncontrast CT image. Note area of increased uptake (arrowhead) on corresponding PET image. In images obtained 2 months after radiofrequency ablation (B), arrowheads point to the much larger low-attenuation region on the CT image and to the corresponding photopenic region on the PET image, which resulted from radiofrequency ablation. No evidence of increased FDG uptake was seen on the postradiofrequency ablation PET/CT study to indicate residual tumor. The patient pictured in A and B was followed by CT imaging (without PET) at 5 and 9 months. Recurrent liver metastasis was demonstrated on the 9-month postradiofrequency ablation CT image (not shown). Another set of PET/CT images were obtained before a second radiofrequency ablation (C) and 2 months later (D). The transaxial planes are the same as shown in Fig. 3A and 3B. In images obtained before the second radiofrequency ablation (C), arrowheads indicate a more extensive abnormality on the CT images than seen in Fig. 3B, as well as new focal abnormal uptake on the PET images. In images obtained 2 months after the second radiofrequency ablation (D), arrowheads point to a larger radiofrequency ablation defect on the CT slices and abnormal FDG uptake on the PET images, which is most likely residual tumor.

Wong et al compared FDG PET with either CT or MR for determining the response of colorectal cancer metastasis to the liver with 90Y-glass microsphere treatment (TheraSphere, MDS Nordion, Ottawa, Canada).34 90Y is a pure β-emitter, with a physical half-life of 64.2 hours, average energy of 0.9367 MeV, and an average penetration range of 2.5 mm in tissue. The glass microspheres are delivered to a hepatic lobe by intra-arterial infusion under low pressure. The short range of the β-emissions results in localized radiotherapy to only the region where the agent is deposited. Thus only liver segments selected for infusion receive radiation delivery as long as arterial venous shunting (to the lungs) is limited. Eight patients were studied before therapy and 3 months later. Twelve hepatic lobes (19 lesions) were injected with all sites showing a decreased metabolic response on the FDG PET study, but only two had anatomic shrinkage on CT or MRI. Posttreatment CEA levels decreased significantly in six of the eight patients. Wong et al later reported on a larger prospective series of 27 patients receiving 90Y-glass microspheres but did not compare them with anatomical imaging studies.35 These patients had diminished FDG tumor uptake 3 months after therapy accompanied by reduced CEA levels consistent with a favorable response to treatment. Similar results were recently reported in a small series of patients with nonresectable liver tumors that were treated with the comparable 90Y-labeled microspheres product (Sir-Spheres, Sirtex Medical, San Diego, CA) (13 patients followed for 3 months posttherapy).36 These small studies show that reduced FDG uptake is seen following this type of regional therapy but there is no published evidence that demonstrate associated marked improvement in long-term survival.

FDG PET FOLLOWING INTERVENTIONAL TREATMENT OF HEPATOCELLULAR CANCER

There is scarce data available in the literature that evaluates the use of FDG PET for characterizing the response of HCC to interventional treatment. In general, investigators agree that monitoring therapy with FDG PET in these patients is only useful if the primary tumor shows avid FDG uptake prior to therapy, a finding that is seen in 50% or less. Although the use of FDG PET to restage colorectal cancer (including those with hepatic metastases) is reimbursable in the United States, it is not for HCC evaluation. This has limited the number of cases reported to almost anecdotal levels.

Torizuka et al used FDG PET to monitor the response of HCC to transcatheter arterial infusion of chemotherapy or embolization therapy delivered in combination with iodized oil.37 PET studies were done 3 to 45 days (mean 26) after the therapy followed by surgical resection 1 to 40 days (mean 11 days) later. The ratio of average FDG tumor uptake to average normal tissue uptake was measured in 30 patients. When the FDG uptake was reduced or absent in the tumor region (corresponding to an uptake ratio less than 0.6), 90% of the lesions showed necrosis on histological exam. Higher FDG tumor uptake values were associated with tumor viability. The PET findings were felt to more accurately depict the extent of viable tumor compared with intratumor iodized oil retention seen on CT images.

No significant series of HCC patients have been reported using FDG PET before and after radiofrequency ablation or 90Y-labeled microsphere treatment. Some of the studies discussed earlier in this article included small numbers of patients with HCC who were treated with both these techniques.

CONCLUSIONS

FDG PET is a useful functional imaging method that complements conventional anatomic imaging modalities for screening patients with hepatic malignancies to determine their suitability for interventional procedures. Abnormal increased FDG uptake is more commonly seen in hepatic metastases, such as those from colorectal cancer, than those from primary hepatic malignancies, such as hepatocellular cancer. The likelihood of detecting hepatic malignancy with FDG PET rapidly diminishes for lesions smaller than 1 cm. The greatest value of FDG PET in these patients is in excluding extrahepatic disease that might lead to early recurrence after interventional therapy. In some cases, more extensive intrahepatic disease is evident on FDG PET compared with conventional imaging methods and may lead to modification of the treatment plan.

Poorly differentiated hepatocellular cancer is more likely to be detected with FDG PET than well-differentiated disease. For hepatocellular cancer, FDG PET is probably useful in the evaluation of extrahepatic disease only if there is increased uptake in the primary lesion.

The number of reported series that examine the role of FDG PET for assessing the response of hepatic malignancies to interventional therapy is limited. Promising results have been reported with FDG PET, which may show residual (local) or recurrent disease before conventional imaging methods in patients receiving interventional therapy. For patients with colorectal hepatic metastases, many investigators believe that patients with PET evidence of recurrent hepatic disease should receive additional treatment even when there is no confirmatory evidence present on other methodologies. For patients with HCC no conclusions regarding the value of FDG PET for assessment of response to interventional therapy can be reached as there is almost no published data.

Earlier problems with FDG PET imaging due to limited spatial resolution have been improved by new inline PET/CT imaging systems that offer registered/fused images that enhance the accuracy of both types of diagnostic imaging. New PET radiopharmaceuticals, such as 11C-acetate, are being investigated, which also have the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy. Functional imaging with PET has a promising future for aiding in the care of patients with hepatic malignancy.

REFERENCES

- Bos R, der Hoeven J van, der Wall E van, et al. Biologic correlates of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in human breast cancer measured by positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:379–387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoch G, Fruedenberg L S, Beyer T, et al. To enhance or not to enhance? 18F-FDG and CT contrast agents in dual-modality 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:56S–65S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl R. In: Wahl R, Buchanan J, editor. Principles and Practice of Positron Emission Tomography. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. Principles of cancer imaging with fluorodeoxy glucose. pp. 100–110.

- Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss L G, Burger C, et al. Prognostic aspects of 18F-FDG PET kinetics in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma receiving FOLFOX chemotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1480–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truant S, Huglo D, Hebbar M, et al. Prospective evaluation of the impact of [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography of respectable colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2005;92:362–369. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasberg S M, Dehdashti F, Siegel B A, Drebin J A, Linehan D. Survival of patients evaluated by FDG-PET before hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal carcinoma: a prospective database study. Ann Surg. 2001;233:293–299. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez F G, Drebin J A, Linehan D C, et al. Five-year survival after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients screened by positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) Ann Surg. 2004;240:438–450. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000138076.72547.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkel K, Lu Y, Both M, et al. Detection of hepatic metastases from cancers of the gastrointestinal tract by using noninvasive imaging methods (US, CT, MR imaging, PET): a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2002;224:748–756. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner R H, Park K C, Shepherd J E, et al. A meta-analysis of the literature for whole-body FDG PET detection of recurrent colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1177–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonneux M, Reffad A M, Detry R, Kartheuser A, Gigot J F, Pauwels S. FDG-PET improves the staging and selection of patients with recurrent colorectal cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:915–921. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalff V, Hicks R J, Ware R E, et al. The clinical impact of 18F-FDG PET in patients with suspected or confirmed recurrence of colorectal cancer: a prospective study. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:492–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford M H, Whiteford H M, Yee L F, et al. Usefulness of FDG-PET scan in the assessment of suspected metastatic or recurrent adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:759–767. doi: 10.1007/BF02238010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohren E M, Paulson E K, Hagge R, et al. The role of F-18 FDG positron emission tomography in preoperative assessment of the liver in patients being considered for curative resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2002;27:550–555. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydzewski B, Dehdashti F, Gordon B A, Teefey S A, Strasberg S M, Siegel B A. Usefulness of intraoperative sonography for revealing hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients selected for surgery after undergoing FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:353–358. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.2.1780353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numminen K, Isoniemi H, Halavaara J, et al. Preoperative assessment of focal liver lesions: multidetector computed tomography challenges magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Radiol. 2005;46:9–15. doi: 10.1080/02841850510016108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzner M, Hany T F, Wildbrett P, et al. Does the novel PET/CT imaging modality impact on the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer of the liver? Ann Surg. 2004;240:1027–1036. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000146145.69835.c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S M, Zondervan P E, Ijzermans J NM, et al. Benign versus malignant hepatic nodules: MR imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:1023–1039. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.5.g02se061023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazumi S, Isono K, Enomoto K, et al. Evaluation of liver tumors using fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET: characterization of tumor and assessment of effect of treatment. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C, Yu S CH, Yeung D WC. 11C-acetate PET imaging in hepatocellular carcinoma and other liver masses. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M A, Combs C S, Brunt E M, et al. Positron emission tomography scanning in the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;32:792–797. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wudel L J, Delbeke D, Morris D, et al. The role of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am Surg. 2003;69:117–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi S, Hishiguchi S, Ishizu H, et al. Usefulness of positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose for predicting outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1877–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J D, Yun M, Lee J M, et al. Analysis of gene expression profiles of hepatocellular carcinomas with regard to 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake pattern on positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:1621–1630. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A T, Rose D M, Pinson C W, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma outcomes based on indicated treatment strategy. Am Surg. 1998;64:1128–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama M, Sakahara H, Torizuka T, et al. 18F-FDG PET in the detection of extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:961–968. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruers T, Bleichrodt R P. Treatment of liver metastases, an update on the possibilities and results. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1023–1033. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostakoglu L, Goldsmith S J. 18F-FDG PET evaluation of the response to therapy for lymphoma and for breast, lung, and colorectal carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:224–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbeke D, Martin W H. PET and PET-CT for evaluation of colorectal carcinoma. Semin Nucl Med. 2004;34:209–223. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoch G, Vogt F M, Veit P, et al. Assessment of liver tissue after radiofrequency ablation: findings with different imaging procedures. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:520–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitola J V, Delbeke D, Meranze S G, et al. Positron emission tomography with F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose to evaluate the results of hepatic chemoembolization. Cancer. 1996;78:2216–2222. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961115)78:10<2216::aid-cncr25>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenhoff B S, Oyen W JG, Jager G J, et al. Efficacy of fluorine-18-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in detecting tumor recurrence after local ablative therapy for liver metastases: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4453–4458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokhuis T J, der Schaaf M C van, den Tol M P van, et al. Results of radio frequency ablation of primary and secondary liver tumors: long-term follow-up with computed tomography and positron emission tomography-18F-deoxyfluroglucose scanning. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2004;241:93–97. doi: 10.1080/00855920410014623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G S, Brinkman F, Soulen M C, et al. FDG positron emission tomography in the surveillance of hepatic tumors treated with radiofrequency ablation. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28:192–197. doi: 10.1097/01.RLU.0000053530.95952.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C Y, Salem R, Raman S, Gates V L, Dworkin H J. Evaluating 90Y-glass microsphere treatment response of unresectable colorectal liver metastases by [18F]FDG PET: a comparison with CT or MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:815–820. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C Y, Salem R, Quing F, et al. Metabolic response after intraarterial 90Y-glass microsphere treatment for colorectal liver metastases: comparison of quantitative and visual analyses by 18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1892–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popperl G, Helmberger T, Munzing W, et al. Selective internal radiation therapy with SIR-Spheres in patients with nonresectable liver tumors. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2005;20:200–208. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2005.20.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torizuka T, Tamaki N, Inokuma T, et al. Value of fluorine-18-PET to monitor hepatocellular carcinoma after interventional therapy. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1965–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]