ABSTRACT

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer worldwide with a wide geographic distribution. The incidence of primary liver cancer is increasing and there is still a higher prevalence in developing countries. Early recognition remains an obstacle and lack of it results in poor outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most prevalent primary liver cancer, and cholangiocarcinoma. The most common risk factors associated with HCC are hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C infections, alcohol use, smoking, and aflatoxin exposure. Emerging risk factors such as obesity might play an important role in the future because of the increasing prevalence of this condition.

Keywords: Primary liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C

PRIMARY LIVER CANCER

Incidence and Trends

WORLDWIDE

Liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer worldwide,1,2 accounting for 5.7% of the overall incident cases of cancer. There is wide geographic variability in incidence with a majority of the cases occurring in developing countries (82%, 366,000 new cases estimated in males in 2002, 147,000 in women) compared with developed countries (74,000 new cases in men and 36,000 women).3 In fact, liver cancer is the third most common cancer in developing countries among men after lung and stomach cancer. It is also between two and eight times more common in men than in women.3,4,5,6 China alone accounts for 55% of the new cases of liver cancer, other high incidence areas being sub-Saharan Africa, Japan, and South-East Asia.3,4,5 Between the years 1978 and 1992, while some centers in high-risk countries like China, India, and Spain recorded a decreasing incidence of liver cancer by as much as 30%, other centers in predominantly low-risk populations like Italy, Australia, and France recorded a nearly 100% increase in the number of cases of primary liver cancer.4 Although some of this increase can be attributed to changes in the coding or diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the modes of treatment of cirrhosis and changing prevalence of the risk factors, particularly hepatitis C virus (HCV), may also play a role.4

There is also a global variation in the risk factors for HCC. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV infections account for 75% of the cases of primary liver cancer worldwide, with an even higher proportion in developing countries.3 Among the two viruses, HBV is more common except in Japan where HCV infection in the most common cause of liver cancer.7 In 1977 to 1978, HBV accounted for 42% of all cases of HCC in Japan. This number decreased to only 16% in 1998 to 1999, but number of cases related to HCV has increased to 70%.7 Alcoholic liver disease accounts for a significant proportion of primary liver cancer cases in the United States and Europe, and both alcohol and tobacco use have significant effects in Asia and Africa.8 Aflatoxin exposure also accounts for a significant number of cases in Asia,8 especially China and Taiwan.

Liver cancer carries a very poor prognosis and is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide.3 Data from both the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End results (SEER) and Eurocare show that primary liver cancer has the lowest overall survival rate worldwide among the 11 most common cancers, with a less than 10% 5-year survival.3

UNITED STATES

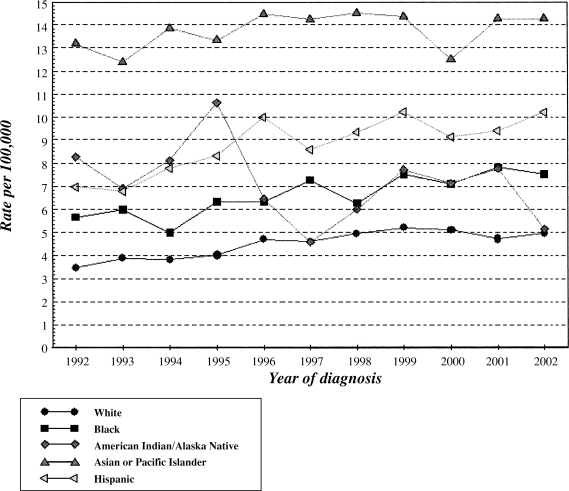

There are an estimated 17,550 new cases and 15,420 deaths due to primary liver cancer in 2005 in the United States9 with an incidence rate of 5.4 per 100 000. Primary liver cancer has shown an average increase in incidence and mortality over the past 10 years, with annual percent changes (APC) of 3.3 and 1.9, respectively (Fig. 1,10). This is in contrast to some of the other common cancers (breast, colorectal, lung, stomach), which have shown either significant decreases or no change in rates for these two parameters.9 Liver cancer has the second highest APC in the time period 1992 to 2002 after thyroid cancer, and the highest APC (1.9) in mortality during the same time period. A majority of these cancers are diagnosed in older patients, with the highest incidence (26.4%) in the age group 65 to 74. The median age of diagnosis is 64 years with a lifetime risk of being diagnosed with liver cancer of 0.89%.9 The mean 5-year survival rates even in the United States is less than 10% with an average of 16.4 years of life lost per person dying of liver cancer.9

Figure 1.

Incidence of primary liver cancer in the United States by race during 1992 to 2002. (Based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results [SEER] Program.10)

A majority of the cases of HCC are related to HCV (47%), HBV (15%), or both (5%).11 Between 1995 and 1996 to 1998, the proportion of HCC patients with HCV nearly doubled from 18 to 31% in a study by Hassan et al, while those with HBV infection or other risk factors decreased slightly.12

HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Several risk factors have been distinctly identified as being associated with HCC. Not surprisingly the prevalence and incidence patterns of HCC follow the patterns of the risk factors that will now be discussed individually.

Specific Risk Factors

HEPATITIS B AND HEPATITIS C

HBV and HCV infection are the main risk factors associated with HCC.13,14,15 In most developed countries HBV and HCV infection are responsible for the majority of these tumors with rates dependent on the regional prevalence of infection. HCC develops from HBV and HCV infection after a latency period of one to three decades.16,17,18 The population cohort most at risk for viral hepatitis (higher incidence of intravenous drug use, needle sharing, and unsafe sexual practice) during the 1960s and 1970s has now gone through this lag period.

Therefore, it follows that an increase in HCC was seen in the 1980s and 1990s. A predictive model suggests that in the United States the incidence of HCV-associated cirrhosis and subsequently HCC will peak in the next decade.27 In the United States blacks and men are more prone to HBV and HCV infection than whites and women.19,20,21 Although HCV infection rates remained steady through out 1980s21 (~150,000 cases annually), they declined dramatically in early 1990s. Nevertheless, some 3.9 million persons in the United States have evidence of HCV infection with ~2.7 million thought to have active viremia. In contrast ~1 to 1.25 million persons are thought to harbor HBV infection with peak incidence of HBV infection reaching 11.5 per 100,000 in 1985 before declining to 6.3 per 100,000 in 1992 and a decline of 67% during 1990 to 2002 largely attributed to the effect of routine childhood vaccination.22 About 55 to 85% of cases of acute HCV and 5% of cases of acute HBV infection become chronic.21

The pathogenesis of HCC in chronic HBV and HCV infection results from a series of steps from proliferation and apoptosis of host cells, inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and eventually dysplasia.23 Nonfibrotic HBV livers may develop HCC,24 whereas HCC in HCV almost universally develops in cirrhotic livers. In a study of 80 cases of HCC arising from nonfibrotic livers, no risk factor for HCC could be identified in 50/80 patients (62%) whereas 17 (21%) were found to have HBV and only 1/80 (2%) had HCV.232 This study supports two notions. First, the majority of HCV patients are at risk for HCC only after cirrhosis develops, and second, HBV patients are at risk for HCC regardless of fibrosis, with the risk of HCC increasing with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. According to National Institute of Health Consensus Statement, the annual incidence of liver cancer is 0.5% in chronic HBV and 2.4% in cirrhotic patients.25

Based on the presumed mechanism of carcinogenesis, the interruption of the sequence of carcinogenesis either by antiviral or anti-inflammatory therapy will diminish the incidence of HCC. Early intervention in the form of HBV immunization has unequivocally reduced the incidence of HCC.26 Treatment strategies directed at eradicating HBV and HCV may also diminish the incidence and/or progression of HCC but this remains to be proven.

Patients with HCV-related cirrhosis have a decreased risk of HCC with interferon (INF) therapy, even without complete biochemical and virological clearing. The current treatment options for HCV include combination therapy of INF plus the guanosine analogue, ribavirin, and most recently to the use of pegylated INF (Peg-INF) in combination with ribavirin.28,29,30,31 The treatment options for chronic HBV in the United States include INF,32,33,34,35,36 Peg-INF, or the nucleoside analogues lamivudine,37,38,39 adefovir,40 and entecavir.41 Unfortunately, patients with decompensated liver disease are poor candidates for INF-based therapies and better-tolerated and more effective therapies are needed.

ALCOHOL

Many studies have shown the association between alcohol and HCC with most studies arriving at an odds ratio (OR) between 1.1 to 6.0.42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 Between 7 and 50% of the cases of HCC have been attributed to alcohol intake depending on the study population.42,50,51,52 Men have a higher attributable risk of alcohol than women.51

Many studies have yielded a dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of HCC.42,46,49,53,54 In a study of 115 patients with HCC and 230 controls in the United States, those with any history of alcohol consumption had an adjusted OR of 2.4 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.3 to 4.4) to develop HCC compared with those with no alcohol intake. After stratifying by amount of consumption, those with <80 mL/d had a modest but not statistically significant increase in OR (1.7, 95% CI: 0.9 to 3.7) compared with nondrinkers, but those with >80 mL/d ingestion of alcohol had a 4.5 (95% CI: 1.4 to 14.8) times greater odds of developing HCC compared with nondrinkers.42 Other studies also found no or reduced risk of HCC with light to moderate alcohol consumption, suggesting a possible threshold effect.44,45,55,56,57 Few studies have compared the risk of HCC with different alcoholic drinks. In a study by Yuan et al, the OR for each 10-g increment of ethanol was 1.12 (95% CI, 1.05 to 1.18) for beer, 1.10 (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.16) for spirits, and 1.07 (95% CI, 0.97 to 1.17) for wine.49

Yuan et al studied 295 cases with HCC and 435 controls in Los Angeles.49 They found an elevated risk of HCC (1.1 to 3.2) with increased alcohol consumption expressed either in drink-years or number of drinks per day. There was no change in risk or a trend toward lower risk in those consuming smaller amounts of alcohol (zero to two drinks per day or <30 drink-years). In a large cohort study from Haimen city in China following 90,000 participants over 8 years, no association between current alcohol consumption and HCC was found in men or women. In fact, those with moderate consumption of alcohol had a slightly lower risk of development of HCC (OR 0.83).56 However, this apparent protective effect of small amounts of alcohol may be fallacious due to the fact that the study participants might have decreased their amount of alcohol consumption after they were diagnosed with HCC.51

Quantifying the exact alcohol consumption that increases the risk of HCC has proven to be difficult because of the different measures of alcohol intake used by different studies. Although some studies measure alcohol consumption as number of grams per day, others use a dichotomous exposure variable, and yet others use both dose and time measures. Donato et al plotted regression curves measuring the relationship between daily alcohol consumption and risk of HCC.54 This revealed a significant elevation above the null with doses greater than 60 g/d in their study.54

Alcohol is associated with HCC in most patients through the development of cirrhosis, which itself is a risk factor for HCC.58,59 But up to 20 to 25% of the cases of HCC can arise in nonfibrotic livers.60 In a series of 80 patients with HCC on the background of no or minimal portal fibrosis in the nontumoral liver tissue, 14% of the cases had only history of heavy alcohol consumption as their risk factor.60 In another study of 174 patients with HCC and 610 controls from Italy, the OR of developing HCC due to alcohol use in the presence of cirrhosis of the liver was 5.5 (95% CI: 3.1 to 9.7) and without cirrhosis, 4.6 (95% CI: 1.5 to 13.8). Fifty-one of the HCC cases both with and without cirrhosis had a history of heavy alcohol consumption.61 Grando-Lemaire et al found 63% of their HCC cases without cirrhosis had a history of intake of alcohol >30 g/d.62 It is yet to be determined whether these cases represent a direct carcinogenic effect of alcohol on the liver cells,60 similar to mechanisms that have been proposed for HBV infection.

Alcohol interacts with other factors in affecting the risk of HCC, most commonly HBV and HCV infections.42,47,51,54 Alcohol has a more than additive effect on the risk of HCC in patients with HBV infection. In a study from Italy, people who were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) had a relative risk (RR) of 9.1 (95% CI: 3.7 to 22.5) for developing HCC compared with those who were negative for antigen and had less than 80 g/d alcohol consumption. People who had >80 g/d alcohol consumption but no HBV infection had an RR of 4.2 (95% CI: 2.4 to 7.4). In the presence of both these risk factors, the OR of developing HCC was 64.7 (95% CI: 20 to 210).51 Although other studies have supported this interaction,63 a few did not find similar results.56,64 There is a similar interaction with HCV infections and alcohol use.47,52 In addition, alcohol has synergistic effect with other risk factors for HCC like smoking,45,64,65 diabetes,42,49 and other environmental exposures.66

HEMOCHROMATOSIS

The association between hemochromatosis and HCC is well known. Some of the early cohort studies report a 200-fold increase in the risk of HCC in patients with genetic hemochromatosis.67 Hsing et al in a population-based study from Denmark found a standardized incidence ratio of 92.5 (95% CI: 25.0 to 237.9) in a cohort of patients with hemochromatosis compared with the expected rates in the population.68 Although later studies have confirmed this association between hemochromatosis and HCC, they have arrived at lower ORs for development of HCC.69,70,71,72,73,74 Whether this reflects earlier identification and treatment of patients remains to be seen.

In a large population study from Sweden, Elmberg et al followed 1847 patients with hemochromatosis for a total of 12,398 person-years.72 A total of 62 cases of liver cancer were identified in this population, corresponding to a 20-fold increased risk. A majority (79%) of these cancers were HCC. There was a difference in the risk of liver cancer between genders. Men with hemochromatosis had a 30-fold increased risk of development of liver cancer, and women had only a sevenfold increased risk. The authors attribute the lower risk in women to blood loss during childbirth and menstruation and lower prevalence of alcohol consumption in women. However, they do not provide data on the prevalence of viral hepatitis or alcohol use in this population, both of which are also significant risk factors for the development of HCC. Fracanzani et al followed a cohort of 20 patients with hereditary hemochromatosis, and 230 matched controls with chronic liver disease. After adjusted for alcohol use, smoking, and family history, the RR for development of HCC in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis was 1.8 (95% CI: 1.1 to 2.9).74 Although most patients with hereditary hemochromatosis develop HCC in a background of liver cirrhosis, there have been case reports of HCC developing even in patients without cirrhosis.62,75,76,77,78,79

Cauza et al found a 20-fold increased risk of HCC in patients with hemochromatosis homozygous for the C282Y mutation of the HFE gene, but they did not find any increased risk in patients heterozygous for this mutation.71 The risk of development of HCC in patients with heterozygous HFE gene mutations is controversial. Some studies did not find an increased risk of HCC in C282Y heterozygotes.80,81 Boige et al found an equal prevalence of C282Y heterozygotes in a population of HCC patients when compared with a control group of patients with cirrhosis who did not have HCC.80 Perl's Prussian blue stain of the liver iron load was similar between heterozygotes and those without the mutation. However, other studies have demonstrated an increased risk of HCC in patients with heterozygous mutations of the HFE gene.82,83,84 Hellerbrand et al analyzed the presence of HFE gene mutations in three populations—137 patients with HCC but no history of hereditary hemochromatosis, 107 patients with cirrhosis without HCC, and 126 healthy controls. They found that heterozygosity for C282Y was more common in the patients with HCC (12.4%) than in patients with cirrhosis (3.7%) or healthy controls (4.8%). There was no difference in the frequency of H63D mutation between the three groups. C282Y heterozygotes had higher levels of ferritin and greater transferrin saturation and more deposition of iron within the HCC tissue as well as nontumor liver tissue, which suggests that C282Y heterozygosity may also have some role to play in the pathogenesis of HCC.83 Fargion et al studied the interaction between HFE gene mutations and other external factors in the development of HCC.82 Among the patients with HCC who were heterozygous for HFE mutations, there was an increased odds of alcohol use or having markers of chronic hepatitis, suggesting that HFE heterozygotes might be more predisposed to develop HCC than those without the gene mutations when exposed to alcohol or viral hepatitis.82 Patients with wild-type HFE genes have a longer survival with HCC compared with those with HCC mutants.85

Different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of HCC in patients with hemochromatosis. Direct toxicity of iron has been postulated to lead to the development of HCC, but mechanisms of how iron causes HCC are incompletely understood. Iron leads to the production of free radicals, which can lead to DNA damage and mutations, which in turn can lead to the development of cancer.71,86,87,88 Higher levels of nitric oxide were found in the liver tissue of patients with hereditary hemochromatosis. Free radical oxygen and nitrogen species can cause an increased incidence of p53 mutations, which can contributed to carcinogenesis.88 Transferrin iron may also have an immunological role to play in the development of HCC by facilitating tumor growth and impairing lymphocyte and macrophage function.89

AFLATOXIN

Aflatoxin is a well-recognized risk factor for the development of HCC. Some of the early studies showing an association between aflatoxin exposure and the development of HCC were from countries that had a high incidence of HCC.57,90,91,92 Omer et al in a study from Sudan determined that 27 to 60% of HCC cases can be attributed to aflatoxin exposure in that country.93

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is the most common aflatoxin linked to HCC. Although many of the early studies used dietary content of aflatoxin as a measure of exposure,57 AFB-DNA adducts in tissues and fluids have been found to be a good measure of exposure status.94,95 One of the first studies using AFB1-albumin as a measure of exposure was by Chen et al in a study of 6487 residents from an HCC endemic area with high mortality in Taiwan. People with detectable AFB1-albumin adducts in their serum had an OR of 3.2 (95% CI: 1.1 to 8.9) to develop HCC compared with those who did not.96 Ross et al in a study of 18,244 people in China found a 3.8 (95% CI: 1.2 to 12.2) times higher risk of development of HCC for patients with evidence of aflatoxin metabolites after adjusting for alcohol, smoking, and HBV status.97

Studies have looked at the association between aflatoxin and other risk factors for HCC. One study in an aflatoxin endemic region in China found that nonsmokers were more likely to develop HCC than smokers, suggesting that cigarette smoke–induced cytochrome P450 activation may blunt the carcinogenic effect of aflatoxin on the liver.98 Other studies have focused mainly on the interaction or synergism between aflatoxin B and chronic HBV infections as both these risk factors have a high incidence in regions of the world where the risk of HCC is the highest. Most of these studies have found an elevated risk with aflatoxin exposure and parallel chronic HBV infection.97,99,100 Wang et al found that people who were positive for both HBsAg and aflatoxin have a greater risk of developing HCC that those with either risk factor or with neither, suggesting that aflatoxin might enhance the carcinogenic potential of HbSAg.100 Different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the synergism between the two risk factors. Chronic HBV infection may induce the cytochrome P450s that metabolize the inactive AFB1 to the mutagenic AFB1–8,9-epoxide. Alternatively, hepatocyte necrosis and regeneration in the setting of chronic HBV infection might predispose the patient to p53 codon 249 mutation when exposed to aflatoxin and subsequent clonal expansions can lead to HCC.101

The mutagenic effect of AFB1 results from hepatic activation to its metabolite AFB-1-exo-8,9-epoxide.102 This induces a G → T transversion at the third position in codon 249 of the p53 gene.103 High rates of these mutations (up to 50%) have been found in some countries in southeast Asia and south Africa, and few mutations were found in Europe, North America, or the Middle East.104,105 Higher rates of these p53 codon 249 mutations in high aflatoxin exposure areas and fewer mutations in low exposure areas has led some authors to suggest that this codon 249 mutation may identify an endemic form of HCC that is associated with dietary aflatoxin intake. These mutations occur at a higher incidence in patients with HCC compared with those with cirrhosis or normal controls.106

DIABETES MELLITUS

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is common in patients with HCC,69 and authors have proposed that up to 8% of the cases of HCC can be attributed to DM in certain populations.44 A causal association between DM and HCC has been difficult to prove for several reasons. End-stage liver disease is associated with glucose intolerance and can lead to the development of diabetes.69 This is a weakness in many of the cross-sectional studies that demonstrate an association between diabetes and HCC. Hemochromatosis can be a confounder in this association as it leads to both increased risk of HCC and DM.69

Although some of the early studies supported an association between DM and HCC,48,107 the findings of some other studies did not concur.108 Moreover, these studies were prior to the identification of the HCV. The first report of the association between HCC and DM came from a study in western Europe by Lawson et al who found a fourfold increased number of diabetics in patients with HCC.109 Since then several studies have supported the association between the two conditions,44,49,69,70,110,111,112,113 most authors finding an adjusted OR of 1.5 to 4.0. Case control studies for causal association of variables suffer from limitations. Information bias might lead to differential reporting of DM between cases (patients with HCC) and controls with higher reports among the cases. However, given that diabetes is a significant lifelong illness, this may not play a significant role.44 Surveillance bias is unlikely given the rapid course of the tumor.44

These biases have been avoided by using the cohort design. One of the largest cohort studies to date was by El-Serag et al who followed over 700,000 patients with and without diabetes using the U.S. Veterans Affairs electronic patient records.112 They found that diabetes was associated with a twofold increase in the risk of development of HCC. They also found a significant temporal association and duration response relationship between DM and HCC.112 People with longer duration of follow-up were more likely to develop HCC. This study also excluded reverse causation (i.e., glucose intolerance caused by decreased liver function) by excluding all those with a history of liver disease prior to enrollment. Diabetes was also significantly associated with HCC even after excluding all patients with history of HBV or HCV infection, alcohol use, or underlying fatty liver disease. However, the generalizability of this study was limited by the fact that most of the patients were male veterans. The first population-based study in the United States was by Davila et al who used data from the SEER-Medicare database and found a threefold greater odds of HCC in patients with DM.69

Different causal mechanisms have been proposed to explain how diabetes can lead to the development of HCC. The hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in diabetes has been proposed to lead to mitogenesis and carcinogenesis in the hepatocytes.113 The insulin resistance also leads to deposition of lipids within the liver, which leads to an oxidative stress. This can lead to microsatellite instability and cell damage, which increases the risk of HCC.49,114 Another mechanism is the worsening of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) due to DM-induced dyslipidemia,44,69,113 which leads to cirrhosis and increased risk of HCC.

Various studies have found synergistic effects between DM and other risk factors for the development of HCC.42,49,69,115 Davila et al showed that in patients with HCV and DM, the odds of developing HCC increased to almost 37.69 Tazawa et al also found that DM increased the risk of HCC in patients with HCV,115 and Hassan et al demonstrated an additive effect between DM and alcohol in the development of HCC.42

SMOKING

The IARC recently added smoking as a causal risk factor for HCC,116 and as much as 25% of cases of HCC may be attributable to smoking.43 But data about the association of smoking and HCC have been conflicting. Early studies showed a significant association between smoking and HCC in populations in Europe,117,118 Asia,43,53,119 and the United States, with most estimations of RR between 1.5 and 3.0. However, many other studies including some recent ones found no association between the two.44,46,61,120,121,122,123

In one of the largest case-control studies looking at the association between cigarette cancer and smoking, Kuper et al compared 333 cases of HCC with 360 hospital controls. They found that cigarette smoking exhibited a significant dose-response relationship with the development of HCC. People who smoke more than two packs a day (OR 1.6, 95% CI: 0.9 to 2.9) were more likely to develop HCC than people who smoked less than two packs a day (OR 1.2, 95% CI: 0.8 to 1.9) or never smoked (OR: 1.0).65 This dose-response relationship has been confirmed by some other studies,56,118 although yet others did not find any such relationship.53,55 Current smokers have a higher risk of HCC compared with former smokers.49,124 Tsukuma et al studied a cohort of 917 outpatients in Japan and found an RR of 2.3 (95% CI: 0.9 to 5.86) and 1.68 (95% CI: 0.63 to 4.47) in current smokers and former smokers compared with nonsmokers, but this difference was not significant. The adjusted risk ratios were higher (7.96 and 3.44, respectively) in patients with liver cirrhosis but were not significantly different from the rate in nonsmokers in patients with chronic hepatitis.124 In a large cohort study of 58,545 men and 25,340 women followed for 8 years in China, there was no association between smoking and HCC in men. In women, those smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day had an RR of 4.2 (95% CI: 1.3 to 13.8), and those smoking six to ten and one to five cigarettes per day had RRs of 2.0 (95% CI: 0.6 to 5.6) and 1.5 (95% CI: 0.4 to 6.3), respectively. However, the number of women who were smokers was small, and the number of HCC cases among women smokers was only eight.56 Jee et al found a similar relationship among men but not among women.43

Smoking interacts with other environmental and viral factors in hepatic carcinogenesis. In a cohort study follow up of 1506 patients in Taipei, Yu et al64 found a greater risk of development of HCC related to smoking in drinkers compared with nondrinkers (RRs of 9.3 and 1.85, respectively), thereby suggesting possible effect modification. Kuper et al also found a super-multiplicative association between cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption in the risk of developing HCC; heavy drinkers who smoke more than two packs a day had an OR of 9.6 (95% CI: 3.4 to 27.5) to develop HCC. This association was seen in the entire study population, as well as in the subclass who were negative for HBV and HCV infection.65 Smoking also increases the risk of hepatitis B–43,125 and hepatitis C–47,126 associated carcinogenesis. Increased proliferation of hepatocytes in viral hepatitis may make the cells more prone to the carcinogenic effect of cigarette smoke and other environmental carcinogens.47

Genetic polymorphisms of many hepatic enzymes have been linked to the development of HCC in smokers, particularly those enzymes involved in the metabolism of environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons commonly found in cigarette smoke.127,128

NONALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease in the United States and may lead to NASH.129 Many case reports have suggested a relationship between NASH and HCC.130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139 In one study of 105 consecutive patients with HCC, at least 13% of the cases were attributable to NASH.134 Although patients in most case reports of HCC associated with NASH had underlying cirrhosis,130,135,137,138 a few cases of HCC were seen in NASH patients without cirrhosis.131,132,136,139 In a series of 641 patients with HCC from Italy, 44 patients had cryptogenic cirrhosis as their underlying risk factor. Most of these patients had other clinical features associated with NAFLD including diabetes and obesity. In a study from Japan comparing HCC related to alcohol liver disease with HCC related to NASH, the only difference was that there were significantly more women in NASH-HCC group.140 Well-differentiated tumors are also more common in HCC associated with cryptogenic cirrhosis, which is a known stage in the natural history of NASH, than those arising from chronic viral hepatitis–related cirrhosis or alcoholic cirrhosis.111

Studies in animals have shown that ob/ob mice (obese mice) have a larger liver than lean mice. This is not accounted for by increased fat deposition but may represent increased hepatocyte proliferation and hyperplasia.141 This obesity-related metabolic change in patients with NASH might increase the risk for HCC in these patients.141,142

OBESITY

Obesity is a recently recognized risk factor for HCC.45,111,143,144,145 Marrero et al compared 70 patients with HCC with 70 patients with cirrhosis and 70 patients with no history of liver disease. Patients with a body mass index greater than 30 had a fourfold increased risk of HCC compared with those with cirrhosis and a 48-fold increased risk compared with those with no history of liver disease.45 However, the carcinogenic effect of obesity may be restricted to patients with alcoholic or cryptogenic cirrhosis, not in patients with chronic viral hepatitis–related cirrhosis or other underlying diseases.111,143 Ratziu et al compared the frequency of HCC in 27 patients with obesity-related cryptogenic cirrhosis and 391 patients with chronic HCV infection-related cirrhosis. They found an equal prevalence of cirrhosis in the two groups, suggesting a comparable carcinogenic potential.144 Obesity has also been shown to interact with alcohol and tobacco in increasing the risk of HCC.146

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the mechanism by which obesity leads to the development of HCC.147 The increased risk of HCC in obese individuals is likely mediated through the development of NAFLD. Hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and elevated insulin-like growth factor levels may act as mitogenic factors and stimulate hepatocyte proliferation.147 Alternately, free radical formation related to fatty liver, which is common in obese individuals, might predispose to the development of HCC.147 With the rising incidence of obesity in the population in the United States, the contribution of this risk factor to the development of HCC may also be increasing.

CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA

Cholangiocarcinoma is the second most common primary liver cancer, accounting for up to 15% of the cases.148,149 Cholangiocarcinomas are of two types, intrahepatic (ICC) and extrahepatic. Some risk factors are well recognized like hepatolithiasis, liver fluke infection, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and thorotrast, whereas other risk factors like viral hepatitis, smoking, and alcohol are still being investigated. Up to half of the cases of ICC have no identifiable risk factors, suggesting other unknown causes.148,150

The role of alcohol as an etiologic factor for cholangiocarcinoma is still debated. In a study from Italy on 26 patients with ICC and 824 controls, no association was found between ICC and alcohol intake.148 Other studies have also found no associations between the two.150,151,152 However, Sorensen et al in a study of 11,605 patients with cirrhosis from the Danish national registry observed 17 cases of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, yielding a standardized incidence ratio of 15.3 (95% CI: 8.9 to 24.5). No cases of cholangiocarcinoma were observed in those with cirrhosis due to viral hepatitis in the same study.153 Another case series from the United Kingdom identified heavy alcohol consumption in up to 45% of 112 patients with cholangiocarcinoma but there was no control group in this series.154 Shin et al also found an association between heavy drinking and cholangiocarcinoma.123

Hepatitis C has more often been linked with cholangiocarcinoma than hepatitis B. Many studies have explored the link between chronic hepatitis B infection and found no association between the two.148,151,155 A large case control study of 103 cases of cholangiocarcinoma found no association between HBV and cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand.152 However, a few other studies have supported the association, reporting between 9 and 12% HBsAg seropositivity in patients with cholangiocarcinoma.156,157

On the other hand, people with chronic HCV infection have an OR between 5 and 10 of developing cholangiocarcinoma.148,150,158 About 35% of patients with cholangiocarcinoma in Japan have circulating anti-HCV antibodies.158 The largest population study of ICC in the United States was by Shaib et al, who used the SEER-Medicare database to identify risk factors in 625 cases with ICC and 90,834 controls. They found that HCV infection had an adjusted OR of 5.2 to 6.1 of developing cholangiocarcinoma.150 Kobayashi et al followed 600 patients with HCV-related cirrhosis for a median of 7.2 years and found cumulative rates of cholangiocarcinoma were 1.6 and 3.5% at 5 and 10 years, respectively, which was ~1000 times higher than the rates in the general population in Japan.159 Different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. HCV RNA sequences have been extracted from cholangiocarcinoma tumor tissue.160 Bile duct epithelial cell injury directly due to HCV or due to associated cholangitis can lead to chronic inflammation and regenerative hyperplasia that can lead to malignant transformation.161

PSC is a well recognized risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma and up to one-third of patients with PSC in some series went on to develop cholangiocarcinoma.162,163,164,165,166 The frequency reported has varied between population-based studies and liver transplantation–related studies with a higher prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in the latter.165 The annual incidence rates range from 0.6165 to 1.5%.162 The time to develop cholangiocarcinoma after the diagnosis of PSC also varied. In a series of 394 patients from five European countries, over half of the 48 patients who developed cholangiocarcinoma did so within the first year,163 whereas Burak et al found the average interval between the diagnosis of PSC and cholangiocarcinoma was 4.1 years.165 Small-duct PSC has a lower incidence of cholangiocarcinoma compared with large-duct PSC.164,167 HLA DR4, DR5 genotypes, K-Ras, and p53 mutations have been associated with an increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma after PSC.168,169 Between 2.5 and 7.5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have PSC. Studies comparing patients with PSC and cholangiocarcinoma to those with cholangiocarcinoma alone have found no difference in the type or duration of IBD,170,171,172 whereas one population-based study from the United States found an OR of 2.3 (95% CI: 1.4 to 3.8) between IBD and cholangiocarcinoma.150

The International Agency for Research on Cancer working group recognized infection with liver flukes (Opisthorchis viverrini, Opisthorchis felineus, Clonorchis sinensis) as a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma.173 It is estimated that ~35 million people are infected with Clonorchis globally, of whom 15 million are in China. In the United States up to 26% of Asian immigrants 20 years ago were found to have an active liver fluke infection,174 though recent studies have identified far lower numbers (1.3%).175 Many reviews have also identified the role of Clonorchis in cholangiocarcinoma.149,176 Shin et al in a study from Korea of 41 patients with cholangiocarcinoma compared with 406 controls found that the presence of Chlonorchis in stool was associated with an OR of 2.7 (95% CI: 1.1 to 6.3).123 A recent review by Choi et al examined the possible mechanisms of carcinogenesis of Clonorchis.177 Liver fluke–induced biliary hyperplasia177 or metabolic products178,179 might act as carcinogens.

Between 2 and 70% of people in northern Thailand have active O. viverrini infection180 due to the traditional habit of eating raw freshwater and salt-fermented fish on a daily basis.181 A case control study of 103 patients with HCC in Thailand found an OR of 5.0 between Opisthorchis infection and cholangiocarcinoma,152 and other studies have confirmed this association.149,182,183 Animal studies have identified inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-mediated nitrate and oxidative damage to the DNA in the bile duct epithelium might be responsible for chronic bile duct inflammation that leads to cholangiocarcinoma.184 It may also induce an inflammatory response through a Toll-like receptor (TLR2)-mediated pathway leading to expression of iNOS and COX-2.185

Hepatolithiasis is a known risk factor for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.149,186 A case control study from Italy compared 26 patients with ICC with 824 controls with no known liver disease; 26.9% of ICC cases and 10.9% of the controls had hepatolithiasis, giving an OR for cholangiocarcinoma of 6.7 (95% CI: 1.3 to 33.4).148 In various series 2.5 to 10% of patients with hepatolithiasis developed cholangiocarcinoma.187,188,189 However, in one series, 43% of patients with ICC had coexisting hepatolithiasis.190 The mechanism of carcinogenesis appears to be related to bile stasis, infection, or mechanical infection.191 Some authors have shown overexpression of transforming growth factor-β (2) and β (3) receptors in hepatolithiasis; 80% of cholangiocarcinoma also have overexpression of the same receptors,192 and other studies have shown a possible role of c-erbB-2 oncogene in both biliary proliferation in hepatolithiasis and cholangiocarcinoma.193

Thorotrast is a suspension of radioactive thorium dioxide and thorium 232 that was used as a contrast agent in the years around World War II.194 It is a well-recognized risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma,149 with cancer developing even decades after exposure.194 ORs have varied from 1.5 to 316.195 Cholangiocarcinoma accounts for 58% of the thorotrast-associated liver cancers.196

Some congenital anomalies of the hepatobiliary system predispose to cholangiocarcinoma, commonly choledochal cysts. Between 5 and 15% of patients with choledochal cysts develop cholangiocarcinoma,176,197,198 with a lower risk in children who present before the age of 10 (overall risk of 0.7%).176 Resection of the cyst appears to decrease the risk of cholangiocarcinoma, but internal drainage for management of cysts may not reduce the risk of cholangiocarcinoma.199 There have been reports of cases of cholangiocarcinoma developing even after resection.200

OTHER PRIMARY LIVER CANCERS

Fibrolamellar Carcinoma

Fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC) is an uncommon tumor usually occurring in younger patients with noncirrhotic livers.5,201,202 It accounts for 0.5 to 1% of all cases of liver cancer.203,204 Although there have been many case reports from different countries reporting FLC, there have been few population-based studies of the epidemiology of FLC. El-Serag et al used the SEER registry to identify epidemiological characteristics of FLC and to compare it with HCC.203 Patients with FLC were younger (39 versus 65 years, P < 0.0001) and more likely to have localized disease and receive curative therapy. However, because the data was registry-based, the authors were not able to identify any risk factors.203 Although some recent case reports have identified the hepatitis B core antigen within the tumor tissue in cases of FLC,205 it is not commonly associated with any of the traditional risk factors for HCC including hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections.5,201 There have also been reports of FLC arising from a previous focal nodular hyperplasia.201

Hepatoblastoma

Hepatoblastoma (HB) is the most common primary hepatic tumor of childhood arising from incompletely differentiated hepatocyte precursors.5,201 It accounts for between 0.2 and 5.8% of all childhood malignant tumors201 and occurs at an incidence of ~1 in 100,000.206 It is also two to three times more common in boys.5,206,207 It is almost exclusively seen in children younger than 3 years, though rare cases have been reported in adults.208 An association with low birth weight has been proposed, with increasing proportion of low-birth-weight babies in infants with this tumor.209,210,211 Other possible risk factors are less forthcoming, but HB is associated with several underlying genetic diseases including Beckwith-Weidman syndrome, Wilms' tumor, and familial polyposis coli.201 Paraneoplastic syndromes, especially isosexual precocity, is also seen in association with this tumor.201,212

Mesenchymal Cancers of the Liver

ANGIOSARCOMA OF THE LIVER

Angiosarcoma of the liver (ASL) is the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the liver, accounting for 2% of all cases of primary liver cancers.213,214 About 10 to 20 cases are diagnosed in the United States each year.213 Peak incidence of the cancer is in the sixth and seventh decades,215 and it is four times as common in men as in women.5 There is a strong association between ASL with occupational exposures.214 However, 75% of the cases are not associated with any known etiologic factors.215 A 45-fold increase in risk of ASL in seen in patients with exposure to the vinyl chloride monomer (VCM).216,217 A review of 20 patients who died from VCM-related ASL showed that the tumor occurred between 9 and 35 years after exposure to VCM.218 The mechanism of VCM-associated ASL appears to be through mutations in ras and p53 genes mediated by the metabolites and adducts of VCM.217 It has also been associated with exposure to arsenic,219,220 thorotrast,221,222 anabolic steroid,215,223 and cyclophosphamide.224 ASL has also been associated with hemochromatosis but not with viral hepatitis.212

EPITHELOID HEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA

Epitheloid hemangioendothelioma is a neoplasm of the liver derived from the endothelial cells.212 The infantile form (infantile hemangioendothelioma) is benign, but the adult variety, which is more common, is malignant.206,212 The epidemiology of this tumor has been poorly characterized because of its rare occurrence, but it has been occasionally reported to be associated with vinyl chloride exposure.6,206

SECONDARY LIVER CANCER

Tumors metastatic to the liver are more common than primary tumors.8 The most common sites of primary tumor are breast, lung, and colorectal cancer.8,225,226,227 In a series of 912 breast cancer patients, 5.2% developed liver metastases.228 Synchronous hepatic metastases may be identified in 10 to 20% of patients with colorectal cancer.229,230 Liver metastases may be rarer in other primary tumors, with only 10% of distant metastases in head and neck cancers present in the liver.231,232 Some authors have reported hepatic metastases in as many as 40 to 50% of adult patients with extrahepatic primary tumors.227 In an autopsy series of 1500 patients with hepatic metastases from unknown primary tumors, Ayoub et al identified primary tumors in the lung, colon, or rectum in 27% of the patients.226

The high incidence of hepatic metastases have been attributed to two mechanisms.227 First, the dual blood supply of the liver from the portal and systemic circulation increases the likelihood of metastatic deposits in the liver. Second, the hepatic sinusoidal epithelium has fenestrations that enable easier penetration of metastatic cells into the liver parenchyma.227

CONCLUSION

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer worldwide with an increasing incidence. The mortality from this cancer is also very high in part due to late recognition of the disease. Among the different liver cancers, HCC is the most common. Although the most common risk factors associated with HCC are HBV and HCV infections, other risk factors like alcohol use, smoking, and aflatoxin exposure also contribute significantly to the burden of this disease, particularly in developing countries. Emerging risk factors like NAFLD and obesity might play an important role in the future because of the increasing prevalence of these conditions. Metastatic liver tumors are more common than the primary tumors and are most commonly of breast, lung, or colorectal origin.

REFERENCES

- El-Serag H B. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemiologic view. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:S72–S78. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200211002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard R, Osteen RT, Gansler T, editor. Clinical Oncology. Atlanta, GA: Blackwell Publishing, Inc; 2001.

- Parkin D M, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn K A, Tsao L, Hsing A W, Devesa S S, Fraumeni J F., Jr International trends and patterns of primary liver cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:290–296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew M C. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, Scharschmidt BF, editor. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. Hepatic tumors and cysts. pp. 1583–1588.

- Fong Y, Kemeny N, Lawrence T S. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editor. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. Cancer of the liver and biliary tree. pp. 1162–1187.

- Kiyosawa K, Umemura T, Ichijo T, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S17–S26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch F X, Ribes J, Diaz M, Cleries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S5–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al, editor. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2002. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2005. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program SEER*Stat Databases. Incidence—SEER 13 Regs Public-Use, Nov 2004 Sub for Expanded Races (1992–2002) and Incidence—SEER 13 Regs excluding AK Public-Use, Nov 2004 Sub for Hispanics (1992–2002), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch released April 2005, based on the November 2004 submission. Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov. Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov

- Di Bisceglie A M, Order S E, Klein J L, et al. The role of chronic viral hepatitis in hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M M, Frome A, Patt Y Z, El-Serag H B. Rising prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among patients recently diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:266–269. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley P A, Sandler R S. In: Everhart JE, editor. Digestive Diseases in United States: Epidemiology and Impact. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1994. Liver cancer. pp. 227–241.

- Kew M C. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, Scharschmidt BF, editor. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. Hepatic tumors and cysts. pp. 1577–1602.

- Takano S, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Tagawa M, Omata M. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B and C: a prospective study of 251 patients. Hepatology. 1995;21:650–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells L, Vargas V, Gonzalez A, Esteban J, Esteban R, Guardia J. Long interval between HCV infection and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver. 1995;15:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1995.tb00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock S. Viruses and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 1994;35:828–832. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.6.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarrish R L, Werner B G, Blumberg B S. Association of hepatitis B virus infection with hepatocellular carcinoma in American patients. Int J Cancer. 1980;26:711–715. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter M J. Epidemiology of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26:62S–65S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelen G D, Green G B, Purcell R H, et al. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in emergency department patients. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1399–1404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205213262105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan G M, Alter M J, Everhart J E. In: Everhart JE, editor. Digestive Diseases in the United States: Epidemiology and Impact. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1994. Viral hepatitis. pp. 127–156.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Incidence of acute hepatitis B: United States, 1990–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;52:1252–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson M A. Hepatitis B virus in hepatocarcinogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:188–202. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199911)181:2<188::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Rikimaru T, Sugimachi K, et al. The importance of hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma originating from nonfibrotic liver. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:531–537. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bisceglie A M, Rustgi V K, Hoofnagle J H, Dusheiko G M, Lotze M T. NIH conference: hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:390–401. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M H, Shau W Y, Chen C J, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination and hepatocellular carcinoma rates in boys and girls. JAMA. 2000;284:3040–3042. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong G L, Alter M J, McQuillan G M, Margolis H S. The past incidence of hepatitis C virus infection: implications for the future burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Hepatology. 2000;31:777–782. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G L, Balart L A, Schiff E R, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with recombinant interferon alfa: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1501–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911303212203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bisceglie A M, Martin P, Kassianides C, et al. Recombinant interferon alfa therapy for chronic hepatitis C: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1506–1510. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911303212204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns M P, McHutchison J G, Gordon S C, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHutchison J G, Gordon S C, Schiff E R, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, et al. Significance of hepatitis B virus DNA clearance and early prediction of hepatocellular carcinogenesis in patients with cirrhosis undergoing interferon therapy: long-term follow up of a pilot study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Suzuki Y, et al. Interferon decreases hepatocellular carcinogenesis in patients with cirrhosis caused by the hepatitis B virus: a pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82:827–835. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980301)82:5<827::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzella G, Accogli E, Sottili S, et al. Alpha interferon treatment may prevent hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1996;24:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oon C J. Long-term survival following treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in Singapore: evaluation of Wellferon in the prophylaxis of high-risk pre-cancerous conditions. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1992;31(suppl):S137–S142. doi: 10.1007/BF00687123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J B, Koff R S, Tine F, Pauker S G. Cost-effectiveness of interferon-alpha 2b treatment for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:664–675. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-9-199505010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstag J L, Perrillo R P, Schiff E R, Bartholomew M, Vicary C, Rubin M. A preliminary trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1657–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstag J L, Schiff E R, Wright T L, et al. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1256–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C L, Chien R N, Leung N W, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K M, Woodall T, Lamy P, Wight D G, Bloor S, Alexander G J. Successful treatment with adefovir dipivoxil in a patient with fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis and lamivudine resistant hepatitis B virus. Gut. 2001;49:436–440. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Man R A, Wolters L M, Nevens F, et al. Safety and efficacy of oral entecavir given for 28 days in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2001;34:578–582. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M M, Hwang L Y, Hatten C J, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2002;36:1206–1213. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee S H, Ohrr H, Sull J W, Samet J M. Cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, hepatitis B, and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1851–1856. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Vecchia C, Negri E, Decarli A, D'Avanzo B, Franceschi S. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in northern Italy. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:872–876. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero J A, Fontana R J, Fu S, Conjeevaram H S, Su G L, Lok A S. Alcohol, tobacco and obesity are synergistic risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2005;42:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayans M V, Calvet X, Bruix J, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Catalonia, Spain. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:378–381. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C A, Wu D M, Lin C C, et al. Incidence and cofactors of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study of 12,008 men in Taiwan. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:674–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M C, Tong M J, Govindarajan S, Henderson B E. Nonviral risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in a low-risk population, the non-Asians of Los Angeles County, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1820–1826. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.24.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J M, Govindarajan S, Arakawa K, Yu M C. Synergism of alcohol, diabetes, and viral hepatitis on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in blacks and whites in the US. Cancer. 2004;101:1009–1017. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga C, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S. Attributable risks for hepatocellular carcinoma in northern Italy. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:629–634. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00500-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato F, Tagger A, Chiesa R, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection, alcohol drinking, and hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study in Italy. Brescia HCC Study. Hepatology. 1997;26:579–584. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi M, Ishizaki M, Takada A. Relative risk for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in alcoholic patients with cirrhosis: a multiple logistic-regression coefficient analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:758–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukuma H, Hiyama T, Oshima A, et al. A case-control study of hepatocellular carcinoma in Osaka, Japan. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:231–236. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato F, Tagger A, Gelatti U, et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: the effect of lifetime intake and hepatitis virus infections in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:323–331. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Hirohata T, Takeshita S, et al. Hepatitis B virus, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study in Fukuoka, Japan. Int J Cancer. 1992;51:509–514. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A A, Chen G, Ross E A, Shen F M, Lin W Y, London W T. Eight-year follow-up of the 90,000-person Haimen City cohort. I: hepatocellular carcinoma mortality, risk factors, and gender differences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J Y, Wang X, Han S G, Zhuang H. A case-control study of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Henan, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:947–951. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goritsas C P, Athanasiadou A, Arvaniti A, Lampropoulou-Karatza C. The leading role of hepatitis B and C viruses as risk factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case control study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:220–224. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199504000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naccarato R, Farinati F. Hepatocellular carcinoma, alcohol, and cirrhosis: facts and hypotheses. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1137–1142. doi: 10.1007/BF01297461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bralet M P, Regimbeau J M, Pineau P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurring in nonfibrotic liver: epidemiologic and histopathologic analysis of 80 French cases. Hepatology. 2000;32:200–204. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.9033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa R, Donato F, Tagger A, et al. Etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italian patients with and without cirrhosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grando-Lemaire V, Guettier C, Chevret S, Beaugrand M, Trinchet J C. Hepatocellular carcinoma without cirrhosis in the West: epidemiological factors and histopathology of the non-tumorous liver. Groupe d'Etude et de Traitement du Carcinome Hepatocellulaire. J Hepatol. 1999;31:508–513. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordier S, Le T B, Verger P, et al. Viral infections and chemical exposures as risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Vietnam. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:196–201. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M W, Hsu F C, Sheen I S, et al. Prospective study of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:1039–1047. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper H, Tzonou A, Kaklamani E, et al. Tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and their interaction in the causation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo G, Fedeli U, Fadda E, et al. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in vinyl chloride workers: synergistic effect of occupational exposure with alcohol intake. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1188–1192. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbear R A, Bain C, Siskind V, et al. Cohort study of internal malignancy in genetic hemochromatosis and other chronic nonalcoholic liver diseases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing A W, McLaughlin J K, Olsen J H, Mellemkjar L, Wacholder S, Fraumeni J F., Jr Cancer risk following primary hemochromatosis: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:160–162. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J A, Morgan R O, Shaib Y, McGlynn K A, El-Serag H B. Diabetes increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a population based case control study. Gut. 2005;54:533–539. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag H B, Richardson P A, Everhart J E. The role of diabetes in hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study among United States Veterans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2462–2467. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauza E, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Ulrich-Pur H, et al. Mutations of the HFE gene in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:442–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmberg M, Hultcrantz R, Ekbom A, et al. Cancer risk in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and in their first-degree relatives. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1733–1741. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelatti U, Donato F, Tagger A, et al. Etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma influences clinical and pathologic features but not patient survival. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:907–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.t01-1-07289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fracanzani A L, Conte D, Fraquelli M, et al. Increased cancer risk in a cohort of 230 patients with hereditary hemochromatosis in comparison to matched control patients with non-iron-related chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:647–651. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg R S, Chopra S, Ibrahim R, et al. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma in idiopathic hemochromatosis after reversal of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1399–1402. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deugnier Y M, Guyader D, Crantock L, et al. Primary liver cancer in genetic hemochromatosis: a clinical, pathological, and pathogenetic study of 54 cases. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:228–234. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh J, Callagy G, McEntee G, O'Keane J C, Bomford A, Crowe J. Hepatocellular carcinoma arising in the absence of cirrhosis in genetic haemochromatosis: three case reports and review of literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:915–919. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199908000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson N P, Stansby G, Jarmulowicz M, Hobbs K E, McIntyre N. Hepatocellular carcinoma arising in non-cirrhotic haemochromatosis. HPB Surg. 1995;8:163–166. doi: 10.1155/1995/46986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellows I W, Stewart M, Jeffcoate W J, Smith P G, Toghill P J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in primary haemochromatosis in the absence of cirrhosis. Gut. 1988;29:1603–1606. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.11.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boige V, Castera L, de Roux N, et al. Lack of association between HFE gene mutations and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 2003;52:1178–1181. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.8.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racchi O, Mangerini R, Rapezzi D, et al. Mutations of the HFE gene and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1999;25:350–353. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1999.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargion S, Stazi M A, Fracanzani A L, et al. Mutations in the HFE gene and their interaction with exogenous risk factors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:505–511. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerbrand C, Poppl A, Hartmann A, Scholmerich J, Lock G. HFE C282Y heterozygosity in hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence for an increased prevalence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauret E, Rodriguez M, Gonzalez S, et al. HFE gene mutations in alcoholic and virus-related cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1016–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirisi M, Toniutto P, Uzzau A, et al. Carriage of HFE mutations and outcome of surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Cancer. 2000;89:297–302. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<297::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargion S, Piperno A, Fracanzani A L, Cappellini M D, Romano R, Fiorelli G. Iron in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1991;23:584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory M A, Kowdley K V. Hereditary hemochromatosis and cancer risk: more fuel to the fire? Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1253–1254. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(01)70014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X W, Hussain S P, Huo T I, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:43–47. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deugnier Y, Turlin B. Iron and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:491–494. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch M C, Chen C J, Levin B, et al. Urinary aflatoxin levels, hepatitis-B virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:931–934. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensburg S J Van, Cook-Mozaffari P, Schalkwyk D J Van, der Watt J J Van, Vincent T J, Purchase I F. Hepatocellular carcinoma and dietary aflatoxin in Mozambique and Transkei. Br J Cancer. 1985;51:713–726. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh F S, Yu M C, Mo C C, Luo S, Tong M J, Henderson B E. Hepatitis B virus, aflatoxins, and hepatocellular carcinoma in southern Guangxi, China. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2506–2509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer R E, Kuijsten A, Kadaru A M, et al. Population-attributable risk of dietary aflatoxins and hepatitis B virus infection with respect to hepatocellular carcinoma. Nutr Cancer. 2004;48:15–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc4801_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J S, Qian G S, Zarba A, et al. Temporal patterns of aflatoxin-albumin adducts in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive and antigen-negative residents of Daxin, Qidong County, People's Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:253–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groopman J D. Do aflatoxin-DNA adduct measurements in humans provide accurate data for cancer risk assessment? IARC Sci Publ. 1988;(89):55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C J, Wang L Y, Lu S N, et al. Elevated aflatoxin exposure and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1996;24:38–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R K, Yuan J M, Yu M C, et al. Urinary aflatoxin biomarkers and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 1992;339:943–946. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91528-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Yang F, Ye Z, et al. Case-control study of cigarette smoking and primary hepatoma in an aflatoxin-endemic region of China: a protective effect. Pharmacogenetics. 1991;1:79–85. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Lu P, Gail M H, et al. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in male hepatitis B surface antigen carriers with chronic hepatitis who have detectable urinary aflatoxin metabolite M1. Hepatology. 1999;30:379–383. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L Y, Hatch M, Chen C J, et al. Aflatoxin exposure and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 1996;67:620–625. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960904)67:5<620::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew M C. Synergistic interaction between aflatoxin B1 and hepatitis B virus in hepatocarcinogenesis. Liver Int. 2003;23:405–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2003.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnowski L, Turner P C, Pedersen B, et al. Increased levels of aflatoxin-albumin adducts are associated with CYP3A5 polymorphisms in The Gambia, West Africa. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:691–700. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200410000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicka S, Trautwein C, Niehof M, Manns M. Target gene modulation in hepatocellular carcinomas by decreased DNA-binding of p53 mutations. Hepatology. 1997;25:867–873. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar F, Hussain S P, Cerutti P. Aflatoxin B1 induces the transversion of G→T in codon 249 of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8586–8590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu I C, Metcalf R A, Sun T, Welsh J A, Wang N J, Harris C C. Mutational hotspot in the p53 gene in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Nature. 1991;350:427–428. doi: 10.1038/350427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk G D, Camus-Randon A M, Mendy M, et al. Ser-249 p53 mutations in plasma DNA of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from The Gambia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:148–153. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adami H O, Chow W H, Nyren O, et al. Excess risk of primary liver cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1472–1477. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.20.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S N, Lin T M, Chen C J, et al. A case-control study of primary hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer. 1988;62:2051–2055. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881101)62:9<2051::aid-cncr2820620930>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson D H, Gray J M, McKillop C, Clarke J, Lee F D, Patrick R S. Diabetes mellitus and primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Q J Med. 1986;61:945–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo M. Association between diabetes mellitus and hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a hospital- and community-based case-control study. Kurume Med J. 2003;50:91–98. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.50.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regimbeau J M, Colombat M, Mognol P, et al. Obesity and diabetes as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:S69–S73. doi: 10.1002/lt.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag H B, Tran T, Everhart J E. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:460–468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagiou P, Kuper H, Stuver S O, Tzonou A, Trichopoulos D, Adami H O. Role of diabetes mellitus in the etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1096–1099. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman K G, Fonseca V, Tan M H, Dalpiaz A. Narrative review: hepatobiliary disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:946–956. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazawa J, Maeda M, Nakagawa M, et al. Diabetes mellitus may be associated with hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:710–715. doi: 10.1023/a:1014715327729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2004;83:1–1438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulos D, Day N E, Kaklamani E, et al. Hepatitis B virus, tobacco smoking and ethanol consumption in the etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1987;39:45–49. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910390109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulos D, MacMahon B, Sparros L, Merikas G. Smoking and hepatitis B-negative primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;65:111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K C, Yu M C, Leung J W, Henderson B E. Hepatitis B virus and cigarette smoking: risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong. Cancer Res. 1982;42:5246–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelatti U, Covolo L, Talamini R, et al. N-Acetyltransferase-2, glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genetic polymorphisms, cigarette smoking and hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:301–306. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Hara M, Wada I, et al. Prospective study of hepatitis B and C viral infections, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and other factors associated with hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Japan. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:131–139. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyong S J, Tsukuma H, Hiyama T. Case-control study of hepatocellular carcinoma among Koreans living in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85:674–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1994.tb02413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H R, Lee C U, Park H J, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus, Clonorchis sinensis for the risk of liver cancer: a case-control study in Pusan, Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:933–940. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.5.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukuma H, Hiyama T, Tanaka S, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1797–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306243282501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima A, Tsukuma H, Hiyama T, Fujimoto I, Yamano H, Tanaka M. Follow-up study of HBs Ag-positive blood donors with special reference to effect of drinking and smoking on development of liver cancer. Int J Cancer. 1984;34:775–779. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910340607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, Matsuzaki Y, Abei M, et al. The role of previous hepatitis B virus infection and heavy smoking in hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1195–1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S Y, Wang L Y, Lunn R M, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in liver tissues of hepatocellular carcinoma patients and controls. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:14–21. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M W, Pai C I, Yang S Y, et al. Role of N-acetyltransferase polymorphisms in hepatitis B related hepatocellular carcinoma: impact of smoking on risk. Gut. 2000;47:703–709. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi Z M, McCullough A J, Ong J P, et al. Obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:705–709. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000135372.10846.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos G K, Arvanitidis D, Tsiakos S, Margantinis G, Grigoriadis K, Kostopoulos P. Is hepatocellular carcinoma part of the natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:88–89. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200307000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencheqroun R, Duvoux C, Luciani A, Zafrani E S, Dhumeaux D. [Hepatocellular carcinoma without cirrhosis in a patient with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:497–499. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)94971-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock R E, Zaitoun A M, Aithal G P, Ryder S D, Beckingham I J, Lobo D N. Association of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without significant fibrosis with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2004;41:685–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Orive A, Garcia-Suarez C, et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatocellular carcinoma. Obes Surg. 2005;15:442–446. doi: 10.1381/0960892053576596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero J A, Fontana R J, Su G L, Conjeevaram H S, Emick D M, Lok A S. NAFLD may be a common underlying liver disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:1349–1354. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Yamasaki T, Sakaida I, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]