Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVM) may be sporadic or occur in association with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also know as Osler-Webber-Rendu syndrome. Several centers nationwide have extensive experience dealing with the latter cohort of patients. These centers have multidisciplinary teams devoted to both diagnosis and treatment of this disease. However, it is not uncommon for patients to present to other hospitals with sporadic PAVMs or to present with initial signs and symptoms of HHT, such as exercise intolerance, stroke, or pulmonary hemorrhage.

Embolization has become the preferred method of treatment for symptomatic PAVMs and asymptomatic lesions > 3 mm in diameter. Incidentally, the 3-mm threshold is a relatively arbitrary criterion based on empirical observation. It was chosen when embolization of smaller lesions was technically impractical with the equipment available at the time. Currently, with the armamentarium of available microcatheters and embolic agents, some interventional radiologists will treat any and all lesions identified on pulmonary angiography. A comprehensive overview of treatment is beyond the scope of this brief article. Instead, I review three embolization techniques useful in the treatment of these lesions and applicable to a wider range of lesions with similar anatomy.

EMBOLIZATION

It is imperative to recognize that embolization of PAVMs is analogous, in many respects, to cerebral embolization. Meticulous attention to detail is crucial; sloppy technique can easily lead to cerebral or cardiac air emboli with serious untoward consequences. Air filters may be placed on all intravenous lines, and some advocate performing all catheter and wire exchanges in a basin of saline to preclude accidental introduction of air into catheters. If blood cannot be aspirated after catheter manipulation, the catheter must be retracted until blood can be aspirated prior to flushing and performing angiography. Intraprocedural heparin administration is recommended by many investigators—typically a 5000 IU bolus followed by 1000 IU per hour.

Detailed pulmonary angiography should be performed in two or three projections to identify all feeding vessels. Lesions supplied by a single segmental pulmonary artery are termed “simple”; those supplied by more than one segmental artery are termed “complex.” The simple types are more common, although it is not unusual for patients with HHT to have both types. Unlike peripheral arteriovenous malformations, proximal embolization of PAVMs has proven to be effective, and the nidus of the lesion does not have to be obliterated. I use a 90-cm 7F guiding sheath and a ≥ 100-cm inner 5F end-hole catheter such as a H1H (Cook, Bloomington, IN) to perform all catheterizations. If necessary, microcatheters are used, although they are not needed in the majority of procedures. I usually perform diagnostic angiography and embolization in the same session, although in patients with more than three PAVMs, I perform staged procedures depending on the technical complexity of the embolization.

The major technical hurdle of effective embolization involves deploying an embolic agent in the desired position when unfavorable anatomy is present. Specifically, if the agent is not carefully chosen and deployed, it could easily pass through the lesion into the systemic arterial circulation.

ANCHOR TECHNIQUE

This technique (and many others) has been described by Dr. Robert White and his colleagues, who have extensive experience in the treatment of PAVMs. To keep the coil from migrating through the lesion, the most proximal aspect of the coil is initially deployed in a small side branch. Then the catheter is withdrawn into the main feeding artery where the remainder of the coil is deposited (Figs. 1 and 2). Either Gianturco steel coils or softer Nestor coils (Cook, Bloomington, IN) can be used, although it is my preference to use the more rigid Gianturco coils initially to provide a scaffold for the softer coils. Typically three or more coils are necessary depending on the length of the coils used. It is important to recognize that thrombosis may not occur for several minutes after embolization.

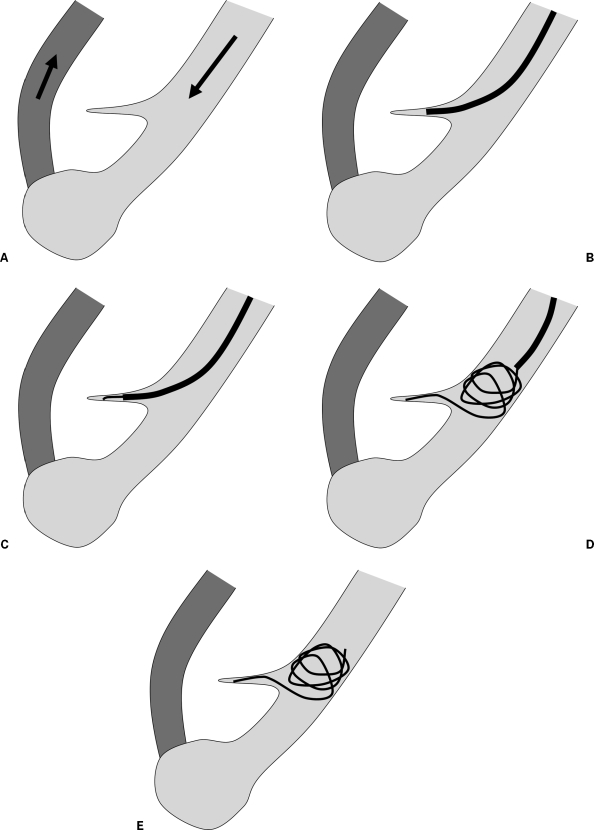

Figure 1.

Anchor technique. (A) Schematic depiction of a simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (B) Illustration shows catheterization of side branch. (C) Illustration demonstrates initial coil deployment into side branch to “anchor” coil. (D) Illustration shows catheter retracted into main feeding artery with deployment of remainder of coil. (E) Illustration shows coil embolization of feeding artery.

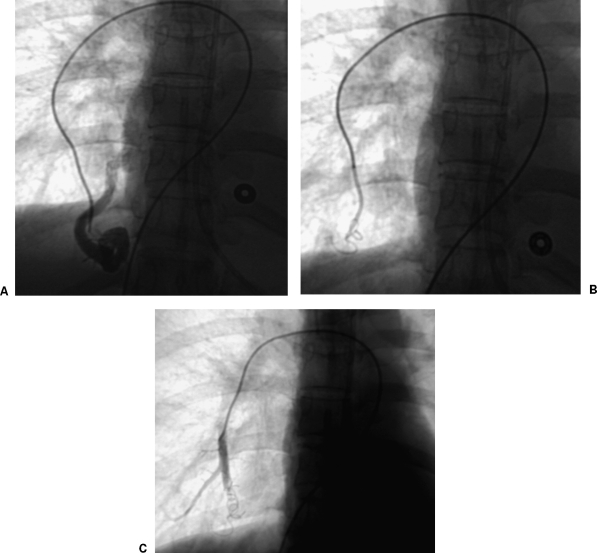

Figure 2.

Embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation using anchor technique. (A) Initial subselective angiogram shows simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (B) Fluoroscopic image shows coil anchored in side branch and partially deployed into main feeding artery. (C) Final angiogram shows complete occlusion of feeding artery.

MICROCATHETER TECHNIQUE USING INTERLOCK COILS

Rarely, the coaxial 5 and 7F catheters do not pass into tortuous anatomy, and microcatheters (advanced through the 5F catheter) may be used. I have found the Interlock Fibered IDC Occlusion System (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) to be very helpful in these cases (Fig. 3). This embolic agent consists of a platinum-tungsten coil with fiber bundling and an interlocking arm mechanism that controls the distal aspect of the coil. The arm mechanism allows the coil to be partially deployed and retracted if positioning is unfavorable. Similar to a detachable coil, it is not released until positioning is optimal. In contrast to a detachable coil, there is a “point of no return” beyond which the Interlock coil is released from the catheter. In my experience, this device is far easier to use compared with detachable coils, and it facilitates subselective embolization. The coil is deposited in a portion of the feeding artery that is uniform in size (proximal to the terminal enlargement that precedes the fistula), and the anchor technique just described can also be utilized as necessary. In general, coils at least 2 mm larger than the artery of interest are chosen.

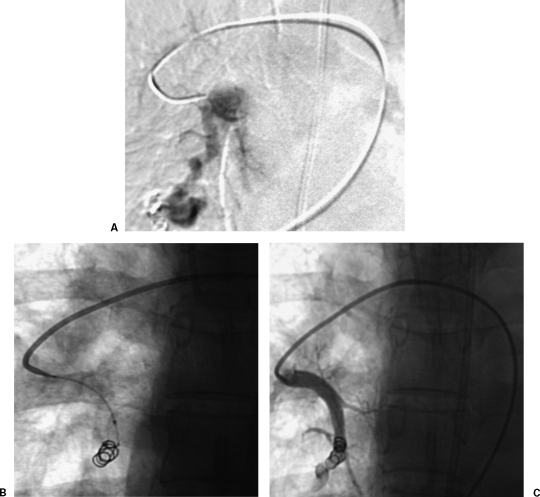

Figure 3.

Interlock coil embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (A) Initial subselective digital subtraction pulmonary angiogram shows simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (B) Fluoroscopic image shows Interlock coil embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (C) Final pulmonary angiogram shows occlusion of feeding artery.

AMPLATZER VASCULAR PLUG

The introduction of the Amplatzer Plug (AGA Medical, Plymouth, MN) has markedly simplified this procedure (Fig. 4). The device ranges in diameter from 4 to 16 mm. The smaller sizes can pass through a 5F guiding catheter and the larger sizes through an 8F guiding catheter with a maximum catheter length of 100 cm. This requires catheterization of the feeding artery by the guiding sheath or catheter. Like the Interlock coils just described, the Amplatzer can be retracted if positioning or size is not optimal. As a general rule, the manufacturer recommends oversizing the coil by 30 to 50%. Clearly, it would be best to err on the side of using a larger device because there is no penalty for oversizing. The device is distributed with a loading sheath. It is flushed, introduced into the guiding sheath, and advanced into the target artery. It expands as it is deployed and is released by twisting the deployment wire in the intuitive counterclockwise direction. If it is not properly seated, it will not “unlock” and can be pulled back into the catheter. In some cases, deployment of an additional coil can be performed to ensure hemostasis, although in my experience, waiting 1 to 2 minutes often enables occlusion to occur without the use of extra embolics.

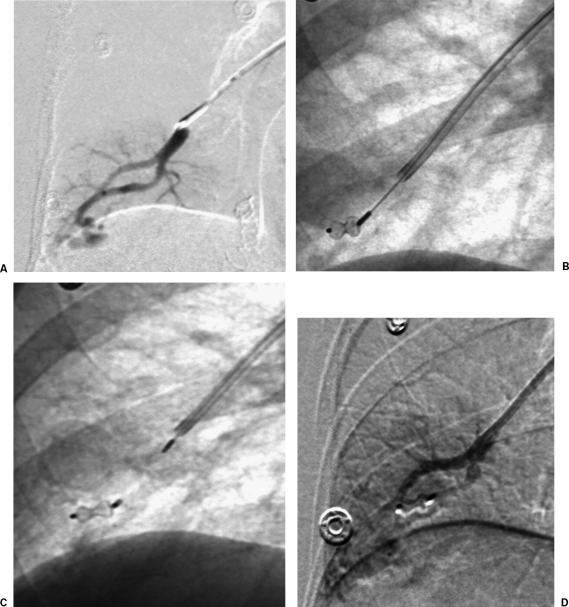

Figure 4.

Amplatzer plug occlusion of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (A) Initial subselective digital subtraction pulmonary angiogram shows simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (B) Fluoroscopic image shows Amplatzer plug advanced into feeding artery. (C) Fluoroscopic image shows Amplatzer plug released into feeding artery. (D) Final subselective digital subtraction angiogram shows occlusion of feeding artery.

DISCUSSION

From a purely technical standpoint, treatment of a PAVM can be likened to occluding any large shunt. The difficulty lies in precisely depositing the embolic agent. These lesions are particularly unforgiving because nontarget embolization is both more likely and less well tolerated compared with other peripheral embolizations. Currently, I prefer the Amplatzer device for this intervention when the feeding artery can be catheterized with a guiding sheath or catheter and the Interlock coils when the microcatheter technique is necessary. Familiarity with all techniques and devices is strongly recommended.

A variety of complications have been reported related to embolization of PAVMs. The most common ones include angina, paradoxical embolus, and either acute or subacute pleurisy. Fortunately, nearly all complications are rare, and most are self-limited. Angina is thought to be due to an air embolus to the right coronary artery. It is typically self-limited and resolves within 20 minutes. Paradoxical embolus occurs in < 1% of procedures and should be exceedingly rare with current embolics. Of course, this complication can be catastrophic and lead to cerebral vascular accident. Pleurisy occurs in ~10% of patients and may be due either to thrombosis of the feeding artery and nidus or infarction or a combination of both. Supportive, conservative therapy is usually all that is required for treatment.

Clearly, most patients with PAVMs are best served by specialized treatment centers, and most are treated in this environment. Nonetheless, knowledge of the techniques described here is valuable for application in other lesions with similar architecture and in the uncommon patient who needs more immediate treatment in other hospitals.

SUGGESTED READINGS

- White R I, Pollak J S, Wirth J A. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: diagnosis and transcatheter embolotherapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7:787–804. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(96)70851-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager J J, Overtoom T T, Bauw H, Lammers J W, Westermann C J. Embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: long-term results in 112 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:451–456. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000126811.05229.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak J S, Saluja S, Thabet A, et al. Clinical and anatomic outcomes after embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:35–44. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000191410.13974.B6. quiz 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]