ABSTRACT

Leiomyomas (or fibroids) are exceedingly common lesions. The indications to initiate treatment are based on the symptoms that can arise from their presence. In general, medical therapy should be considered the first line of treatment. Currently, the treatment of fibroids is in evolution. Since uterine artery embolization (UAE) was first described by Ravina et al in 1995, it has been shown to be a safe, efficacious, and cost-effective alternative to traditional surgical options, with data from long-term studies now available. Appropriate patient evaluation and selection are vital; the ideal candidate is one who is premenopausal, has symptomatic fibroids resistant to medical therapy, no longer desires fertility, and wishes to maintain her uterus. Uterine artery embolization is primarily an angiographic procedure, but periprocedural clinical management is critical for patient satisfaction. This article discusses the various embolic materials that are commonly used and available for UAE; understanding the technical nuances is critical for long-term success.

Keywords: Uterine artery embolization, fibroids, embolic material

Leiomyomas, more commonly referred to as uterine fibroids, are benign tumors composed of smooth muscles and an extracellular matrix of collagen and elastin. They are exceedingly common lesions, occurring in up to 50% of women in some ethnic groups (the incidence is greatest among women of African descent), but most remain asymptomatic. The indications to initiate treatment for fibroids are based on the symptoms that arise from their presence. Among these are uterine bleeding, pain, and bulk-related complaints (such as urinary frequency, constipation, and ureteral obstruction). Using objective measures, the severity of symptoms has not been shown to correlate with fibroid size. This means that even small fibroids can have a significant impact on the quality of a woman's life. Of all the hysterectomies performed annually in the United States, 30 to 40%, or nearly 200,000, are performed as a result of symptomatic uterine fibroids.1

The ready availability of information regarding minimally invasive treatment options combined with a general and quite understandable desire of women to avoid surgery have prompted a broad interest in uterine artery embolization (UAE) procedures. For several years after the procedure was first described by Ravina et al in 1995, UAE was the subject of controversy regarding its potential benefits compared with the traditional standards such as hysterectomy and myomectomy.2 However, since that time both short- and long-term studies have validated the safety, efficacy, and benefits of the procedure when compared with traditional surgical options. Siskin et al published a prospective multicenter comparative study between myomectomy and UAE related to the long-term clinical outcomes and concluded that UAE was associated with greater sustained improvements in symptom severity and health-related quality of life with fewer complications.3 More recently, Goodwin et al show that UAE results in a durable improvement in quality of life for women in an outcomes study. Currently, ~25,000 UAE procedures are performed annually in the United States.1

The estimated costs for inpatient surgical care for fibroids totaled more than $2 billion dollars in 1997. Uterine artery embolization is less expensive than hysterectomy even when accounting for potential need of repeat procedures or associated complications.4 Hysterectomy is a major surgical procedure typically requiring 5 days of hospitalization for the immediate postoperative recovery, and the long-term recovery period can range from 4 weeks to as long as 6 months. Patients treated for symptomatic fibroids with a UAE procedure are typically discharged the following day after symptomatic care and an observation period. In addition, most can return to ambulatory activities and work well within a month and often earlier.

PREPROCEDURE EVALUATION

Becoming familiar with and selecting the appropriate candidates for a uterine fibroid embolization procedure is vital. A careful history and complete evaluation should be performed as part of the patient's workup in preparation for a UAE procedure and should include close consultation with the patient's gynecologic care provider. Ideally, the interventional radiologist planning to perform the procedure should have a preprocedure outpatient clinic consultation visit with the patient to develop a relationship and offer the opportunity to discuss the procedure, its risks and benefits, and the expected outcome in detail with no time pressure constraints. It is not unusual for the patients spouse or partner to attend the consultation with the patient.

Indications

The most common presenting symptoms of fibroids are menorrhagia/metrorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, and bulk symptoms. Bleeding problems tend to present early, when fibroids are relatively small. The degree of bleeding can be dramatic, causing marked anemia and chronic fatigue. In contrast, bulk symptoms present later, when the fibroids have grown larger. Bulk symptoms vary in degree with the size of the fibroids and their mass effects on adjacent organs such as the bladder or rectum. Fibroid symptoms can have a significant impact on the quality of life that is comparable to other major chronic diseases.

There are numerous medical therapies for uterine fibroids, but these are beyond the scope of this document. So, too, are the surgical options including myomectomy. Uterine artery embolization should be considered in consultation with a women's health care specialist who can counsel the patient about these alternative therapies. In general, medical therapies should be used if they are effective, with surgery and UAE being offered only when medical therapy fails.

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindications to UAE are current pelvic or gynecologic infection and current pregnancy. Relative contraindications include those that would be considered for any angiographic procedure: uncorrectable coagulopathy, severe renal insufficiency, and a history of anaphylactic reactions to radiographic contrast media. Another relative contraindication is a peri- or postmenopausal state. Perimenopausal women are likely to experience significant spontaneous improvement in their symptoms once menopause is reached, and may therefore need no treatment at all. However, the perimenopausal state can be difficult to diagnose and quite protracted, so it should not preclude treatment in very symptomatic women. The concern is different for women who have already passed through menopause. In this population, the new onset of uterine bleeding or enlargement of a uterine mass suggests a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, rather than a benign fibroid. Great care should be taken to avoid organ-sparing therapy in a patient who would be better served by resection of a malignant lesion.

Fertility Issues

Fibroids are associated with diminished fertility and with increased risk of pregnancy complications such as preterm labor, placental abruptions, breech presentation, and the need for caesarian section delivery.5 Reducing fibroid bulk is thus seen as a technique for improving the likelihood of a successful pregnancy. However, there have been no randomized studies involving fertility and pregnancy outcome for patients who desire to become pregnant after UAE. Numerous successful post-UAE pregnancies have been anecdotally reported,6 but published studies have also demonstrated diminished ovarian function in older patients after UAE and an increased incidence of complications during pregnancy in women who do become pregnant after UAE.7,8 Therefore, it is currently recommended by the Society of Interventional Radiology and other groups that UAE not be offered as first-line therapy for patients with an explicit desire for future pregnancy. In such individuals, myomectomy is preferred, with UAE reserved for individuals who cannot or will not undergo myomectomy. Women who desire the possibility of future pregnancy should be counseled carefully regarding the uncertain effect of embolization on fertility and pregnancy.9

Patient Evaluation and Selection

For the reasons discussed previously, the ideal candidate for UAE is one who is premenopausal, has symptomatic uterine fibroids resistant to medical therapy, no longer desires fertility, and yet wishes to maintain her uterus.10 Identifying such individuals requires a detailed discussion with the patient and a thorough evaluation of her medical record.

A recent examination by the patient's gynecologic provider, including a pap smear and endometrial biopsy, are particularly important for excluding malignancy as the potential etiology for those patients presenting with menorrhagia or bleeding. Because UAE is an angiographic procedure with the attendant risks and the required use of iodinated contrast, certain laboratory tests including complete blood count (CBC), renal function tests, coagulation profile, and a pregnancy test should routinely be requested. Other tests that can be considered are follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol levels before and after the procedure. These studies are done to assess baseline and postprocedure ovarian function, and may be of interest due to the potential for ovarian injury during UAE.7

Imaging studies play a key role in the preparation for a UAE procedure. The presence, number, and location of the fibroids must be documented. Imaging is also helpful to exclude alternative diagnoses such as adenomyosis and pelvic masses other than fibroids that could account for the patient's symptoms and presentation. Although an ultrasound is generally sufficient to demonstrate the uterine anatomy and presence of fibroids, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has increasingly been favored by interventional radiologists. A contrast-enhanced MRI has the advantage of providing not only improved localization and size of the fibroids, but also the enhancement characteristics of the fibroids (Fig. 1). In addition, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can be performed to give a preview of the pelvic vascular anatomy (Fig. 2).

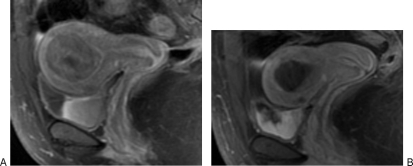

Figure 1.

(A) A 44-year-old African American woman with history of menorrhagia, pelvic pain, and urinary frequency. Saggital T1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast shows a diffusely enhancing intramural fibroid that measures 5.5 × 4.2 cm with associated mass effect on the bladder and displacement of the endometrial cavity. There is also a smaller anterior intramural fibroid. (B) At 6-month follow-up, MRI after uterine artery embolization (UAE) demonstrates complete infarction of the fibroid with significant decrease in size of the tumor, which now measures 2.7 × 2.1 cm. There is normal enhancement of myometrium. The patient was symptom free at follow-up.

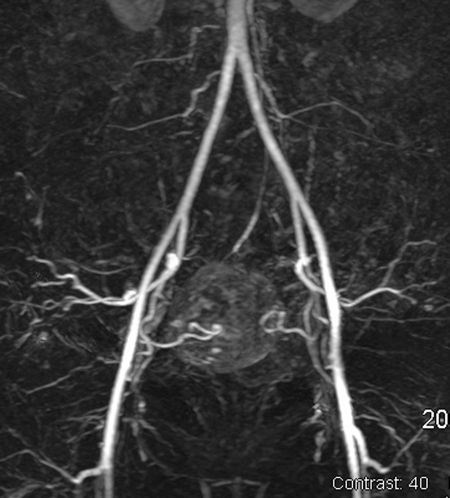

Figure 2.

A 41-year-old white woman presented with menorrhagia, anemia, and chronic fatigue. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) demonstrates conventional bilateral uterine artery anatomy supplying a fibroid uterus with a large enhancing mass.

PROCEDURE

The UAE procedure is routinely performed using intravenous (IV) “conscious sedation” techniques. Before initiating the procedure, the patient should have a Foley catheter placed to drain the bladder of urine and prevent excreted contrast in the bladder from obscuring visualization of pelvic structures. Infectious complications related to the procedure are uncommon, but a prophylactic IV antibiotic is commonly employed, such as cefazolin (or vancomycin in patients allergic to penicillin).11 Shortly after the initiation of embolization, significant pain can ensue as a result of tumor infarction and the inflammatory response. Ketorolac is a useful nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication with potent analgesic effects.12 We routinely use 60 mg of IV ketorolac during the course of the procedure; 30 mg of IV ketorolac is given during the embolization of each uterine artery.

A unilateral or bilateral femoral artery access technique can be used, depending on operator preference. Those who opt for the former generally do so to reduce the number of punctures and thereby the likelihood of access site complications, whereas those who prefer the latter cite the reduced radiation dose that comes with performing bilateral selective arteriograms simultaneously. Once access has been achieved, a pelvic angiogram is often performed to map the uterine arterial contribution. Some authors obtain this study with a flush catheter positioned at the level of the renal arteries to identify any significant supply to the uterus and fibroids from the ovarian artery (Fig. 3). This is followed by selective catheterization of the uterine arteries bilaterally. If a bilateral access has been used, both uterine arteries can be catheterized and studied at the same time, often using a relatively simple catheter. If a unilateral femoral access technique is used, the two arteries need to be addressed sequentially, and catheterization of the ipsilateral uterine artery will require somewhat more complex angiography techniques such as forming a Waltman loop with an end-hole catheter or use of various commercially available catheters (Fig. 4).

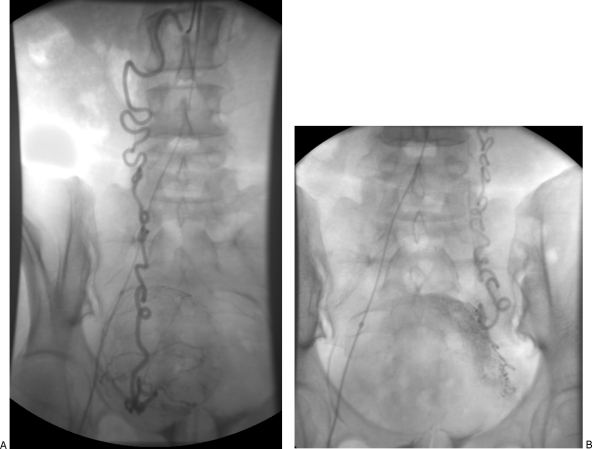

Figure 3.

This patient had no identifiable uterine artery vascular supply to a large uterine fibroid. Aortogram and subsequent selective ovarian artery catheterization demonstrated that the ovarian arteries bilaterally provided the arterial supply for the fibroid. The markedly tortuous course of the ovarian arteries precluded the ability to perform an embolization procedure due to the need to pass a microcatheter beyond the ovarian branch. (A) Selective right ovarian artery angiogram demonstrates a hypervascular enhancing uterine fibroid mass. (B) Selective left ovarian artery angiogram also demonstrates arterial contribution to the fibroid.

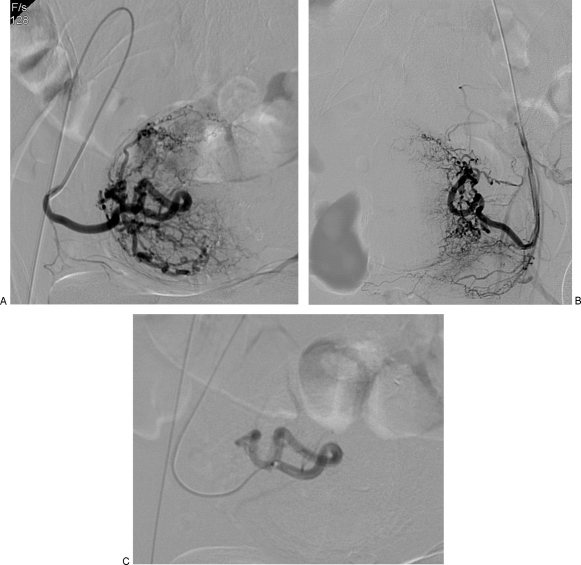

Figure 4.

(A) Same patient as in Fig. 2. Selective oblique view angiogram of the right uterine artery after forming a Waltman loop with an end-hole catheter from an ipsilateral puncture. There is identification of the cervicovaginal branch. (B) Contralateral left uterine artery angiogram. (C) Postembolization angiogram after introduction of a microcatheter that was advanced beyond cervicovaginal branch. Embolization was performed using 355 to 500 μm nonspherical polyvinyl alcohol. Angiogram shows stasis of the contrast column for several heartbeats and no further enhancement of fibroid mass.

Once the internal iliac artery is accessed with a 4F or 5F catheter, many interventional radiologists prefer to select the uterine arteries using a microcatheter and wire to decrease the risk of inducing vasospasm. Safe and effective embolization of uterine fibroids relies on preferential flow to the tumor. Embolization in the setting of vasospasm can lead to prolonged procedure time or worse: vasospasm can lead to inadequate embolization by producing a “false-endpoint” appearance of the fibroid vasculature. Incomplete occlusion, in turn, increases the risk of treatment failure and persistent or recurrent symptoms. It is essential to avoid and/or appreciate vasospasm and address it appropriately. Should vasospasm be encountered or induced, this can be addressed by using a vasodilator such as intra-arterial or transdermal nitroglycerin.13 Intra-arterial lidocaine is not recommended.

Whatever catheter style is used, its tip should be positioned in the transverse portion of the uterine artery and selective arteriography performed. If the cervicovaginal branch of the uterine artery is identified, and if it is technically feasible to do so, the tip of the catheter should be advanced beyond this branch. Embolization of the uterine artery and its supply to the fibroids can than proceed to a defined endpoint (Fig. 4). The various embolic materials commonly used for UAE and the endpoints of embolization are discussed separately in this article. Both uterine arteries should be selectively embolized to achieve maximal efficacy. Although there have been reports describing symptomatic benefit out to 4 years when embolization was limited to a single artery for various reasons,14 larger studies have clearly shown an increased clinical failure rate when bilateral embolization cannot be performed.15

POSTPROCEDURE MANAGEMENT

In addition to the usual postprocedure requirements associated with an arterial puncture, the major treatment issues following UAE relate primarily to postembolization syndrome (PES), which consists of pelvic pain, nausea/vomiting, and low-grade fevers. Aggressive and effective treatment of PES, especially pain, is critically important for patient satisfaction.

Establishing an effective pain management strategy must be initiated before the start of the procedure if postprocedure discomfort is to be controlled effectively. At our institution, patients undergoing UAE are provided with a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump. The PCA can be prepared with various narcotic medications depending on institutional protocols. The patient should be educated on its use and the PCA available immediately following the procedure (if not during the procedure) with a prescribed basal rate and timed lock out intervals. Patients can typically be converted over to oral analgesia medications the following day. In addition, we also routinely use intraprocedural ketorolac to forestall postembolization pain. Some authors also use dexamethasone as part of their treatment to reduce both the inflammatory response and nausea associated with the embolization.16

Nausea and vomiting are not uncommon with postembolization syndrome. Aggressive hydration and the liberal use of IV antiemetics in the period following the procedure should be part of the postprocedure regimen. It is not uncommon that more than one class of antiemetics is required to adequately control a patient's symptoms. Consideration can be made for prescribing the suppository form of an antiemetic medication as opposed to the oral form. At the time of discharge the patient should be able to adequately tolerate oral intake.

Low-grade fevers can be seen in up to 40% of women in the period following a UAE procedure and should not be mistaken for an indicator of an impending infectious complication. Infectious complications are uncommon, but close surveillance is prudent given the potential morbidity of such an event. No studies support the need for routine use of postprocedural antibiotics.11 Typically, the fevers can be managed with acetaminophen, which can be prescribed alone or as an acetaminophen/narcotic combination that will also assist with pain control.

Our postdischarge protocol includes telephone contact with the patient by 24 to 48 hours following discharge and a clinic visit at 1 week. This provides the opportunity to evaluate the patient for possible complications and for the adequacy of pain and nausea control. Our patients are scheduled for another clinic visit and a follow-up imaging study 6 months following the procedure to assess their clinical response and the degree of tumor infarction (Fig. 1). Some authors advocate earlier imaging follow-up and will offer repeat embolization if residual fibroid perfusion is identified. Incompletely infarcted fibroids have a potential for regrowth and recurrence of symptoms.17

EMBOLIC MATERIAL

Various embolic agents have been used for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. All of the early published series regarding UAE used nonspherical polyvinyl alcohol (nPVA) particles. Since then, other agents have been used successfully, including Gelfoam, tris-acryl gelatin microspheres (TAGMs), and spherical PVA (sPVA). Several studies from Japan, where Gelfoam is the preferred agent, have shown it to work quite well.18 Similarly, a randomized trial by Spies et al showed no significant difference in outcomes with UAE performed using nPVA versus TAGM.19 However, a similar evaluation of sPVA by the same group showed such poor results that the study was terminated.20 Clearly there are significant physical differences among the agents currently available; these lead to technical differences in their use that are quite important and with which the interventional radiologist should be familiar.

Nonspherical PVA particles can have extensive size variation within a sample. In addition, because they are hydrophobic, PVA particles tend to aggregate. As a result of these features, the effective size of the nPVA particles varies widely. Nonspherical PVA aggregates have a tendency to occlude the angiographic catheter and, because they are larger than the individual particles of which they are comprised, are unable to penetrate into the deep central vascular supply of the fibroid tumor. Over several minutes in situ, nPVA aggregates collapse, allowing the individual particles to penetrate more deeply and reestablishing flow in the larger trunk. If one is unfamiliar with this characteristic of nPVA, one might terminate embolization prematurely, resulting in incomplete treatment. Because they are irregular in shape, individual nPVA particles may not completely occlude the vascular lumen. Instead, they may induce an intimal injury similar to a foreign body reaction that initiates platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. It is the thrombus formation with the nPVA serving as the supporting network that leads to vascular occlusion and resultant infarction of tumor.21 A common practice for nPVA is to start with 355 to 500 μm particles and then upsize to 500 to 710 μm particles if flow is not reduced after delivery of 2 to 4 cc of particles.19 The endpoint for embolization using nPVA is near stasis of antegrade flow in the uterine artery, with persistent opacification of the main trunk after contrast injection. Once this point has been reached, the operator should wait 2 to 5 minutes to allow any remaining aggregates to collapse and should then reconfirm adequate stasis with repeat angiography.

Tris-acryl gelatin microspheres, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human use in 2002, are embolic particles that are calibrated for a more consistent size. They are slightly compressible and, because they are hydrophilic, do not aggregate. These characteristics allow a more laminar passage of particles through the catheter and vessel, resulting in deeper penetration and more distal occlusion. In addition, their round cross-section matches that of the vascular lumen, allowing a single particle to completely occlude a vessel of matching size. Because of these differences in penetration and mechanism of occlusion compared with PVA, some have advocated an earlier endpoint for embolization than described previously. This endpoint has been described as having a “pruned tree” appearance on the final angiographic run, in which there is occlusion of the distal uterine arterial branches and those that penetrate the fibroid, but with sluggish antegrade flow in the main uterine artery and a persistent contrast column through five heartbeats.17,19 We routinely start with 500 to 700–μm particles and upsize to 700 to 900–μm particles if needed.

Gelfoam is a protein-based, water-insoluble hemostatic material that is frequently used for intravascular embolization. In fact, although it is not approved by the FDA for intravascular use, Gelfoam has been effectively and safely used for uterine artery embolization procedures to control postpartum hemorrhage or pelvic trauma over the past several decades. It is generally considered a “temporary” or short-term embolic material because it is degraded within 7 to 21 days. Thus, the vascular occlusion initiated by Gelfoam is often recanalized within several weeks to months.21 Like nPVA, Gelfoam initiates an arteritis type of reaction within the vessel causing an inflammatory reaction leading to thrombus formation. Long-term prospective studies evaluating Gelfoam for UAE procedures have shown similar clinical results as nPVA and TAGM.22 Follow-up MRI and MRA imaging has confirmed the ability of Gelfoam to produce complete fibroid infarction as well as permit the recanalization of the uterine artery.23 The latter feature has lead some authors to suggest that Gelfoam is the agent of choice for patients who may be interested in future pregnancies. Gelfoam slurry is made from a cut sheet of gelatin sponge material that is agitated vigorously between two syringes and a three-way stopcock. The slurry consists of particles measuring ~500 to 1000 μm that cause a more proximal occlusion than PVA or TAGM. The endpoint of embolization is complete stasis of antegrade flow in the main uterine artery.

Spherical PVA has been developed in recent years to provide an embolic particle that, like TAGM, is uniform in size and conforms better than nPVA to the cross-sectional area of blood vessel. However, multiple studies comparing the efficacy of sPVA with that of nPVA and TAGM have shown disappointing results.19,22,23 The manufacturer of sPVA currently recommends using larger particle, 700 to 900 μm, for UAE procedures.24 The endpoint is uncertain, but should probably be more aggressive than for nPVA. Complete uterine artery stasis is probably an appropriate goal.

Except for sPVA, the agents described in this article have similar effectiveness for use in UAE procedures. The greatest benefit of TAGM is a result of the calibrated size and ease of use, particularly with microcatheters. However, the deeper penetration has been reported to require a greater volume and potentially leads to increased cost. On the other hand, TAGM has only been used in human embolization procedures for some 5 years, whereas nPVA has an extremely long history of use in humans and thus a very good record of safety. Some patients ask for Gelfoam by name because they wish to avoid a permanent implant. Both PVA and TAGM are readily available commercially in the United States and Europe. However, Gelfoam may be the particle of choice when PVA and TAGM are not commercially available or when patients specifically desire a temporary agent.

COMPLICATIONS

Other than PES—which is an expected side effect, rather than a complication—the overall adverse event rate is low following UAE procedures. The most common complications are those related to incomplete relief of symptoms (seen in roughly 15%), whereas the most severe are infections requiring surgical intervention. The need for hysterectomy as a result of uterine injury or infection is exceedingly rare. In fact, the rate of major complications for UAE is lower than that of surgical intervention for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids.25

The overall complication rate for UAE is reported to be 10.5%, with the vast majority of complications regarded as minor.26 Most of these are related to the angiographic component of the procedure and include problems such as puncture site hematoma. Other angiographic-related complications include contrast allergy, nephrotoxicity, and nondirected embolizations in which ovarian arterial anastomoses are inadvertently embolized from the uterine artery. This can potentially result in induction of early ovarian failure and amenorrhea. Induction of amenorrhea after UAE procedures is uncommon and most frequently seen among patients who are older than 45 years and/or perimenopausal.7

TECHNICAL FAILURE

There are several well-documented potential sources of technical failure. These include failure to catheterize one or both uterine arteries; vasospasm or clumping of embolic material leading to a false embolization endpoint; and unrecognized collateral vascular supply to the uterus and fibroid, the most common source for which is the ovarian artery27 (Fig. 3). Failure to recognize and/or treat prominent ovarian collateral supply can result in treatment failure. These ovarian vessels are typically hypertrophied, whereas a normal ovarian artery is less than 1 mm in diameter and generally not detectable angiographically. There have been reports of successful embolization of ovarian collaterals to fibroids in which the ovarian artery is selectively catheterized beyond the ovarian supply with favorable results.28

CONCLUSION

The treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids is in evolution. Since the Ravina et al description of UAE as an effective treatment potential, numerous studies have shown it to be a safe, effective, and cost-effective alternative to traditional surgical approaches. There is a low rate of significant adverse events with a high technical success rate that can be achieved when the procedure is performed in experienced interventional radiology practices in both the community and academic setting. The fact that greater than 85% of patients would recommend the procedure to a friend or family member speaks for itself.1 As a result, UAE should routinely be considered as a treatment option for women that have symptomatic uterine fibroids.

REFERENCES

- Goodwin S C, Spies J B, Worthington-Kirsch R, et al. Uterine artery embolization for treatment of leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000296526.71749.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravina J H, Herbreteau D, Ciraru-Vigneron N, et al. Arterial embolisation to treat uterine myomata. Lancet. 1995;346:671–672. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siskin G P, Shlansky-Goldberg R D, Goodwin S C, et al. A prospective multicenter comparative study between myomectomy and uterine artery embolization with polyvinyl alcohol microspheres: Long-term clinical outcomes in patients with symptomatic uterine fibroids. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1287–1295. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000231953.91787.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu O, Briggs A, Dutton S, et al. Uterine artery embolisation or hysterectomy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: a cost-utility analysis of the HOPEFUL study. BJOG. 2007;114:1352–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of uterine fibroids. Summary, evidence report/technology assessment: Number 34. AHRQ Publication No. 01–E051, January 2001 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/clinic/epcsums/utersumm.htm Available at http://www.ahrq.gov.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/clinic/epcsums/utersumm.htm

- Usadi R S, Marshburn P B. The impact of uterine artery embolization on fertility and pregnancy outcome. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:279–283. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3281099659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies J B, Roth A R, Gonsalves S M, et al. Ovarian function after uterine artery embolization: assessment using serum follicle-stimulating hormone assay. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:437–442. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg J, Pereira L, Berghella V. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:869–872. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, et al. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata; the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:67–76. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000149156.07061.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshburn P B, Matthews M L, Hurst B S. Uterine artery embolization as a treatment option for uterine myomas. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33(1):125–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan D K, Beecroft J R, Clark T W, et al. Risk of intrauterine infectious complications after uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1415–1421. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000141337.52684.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui W L, Kwong W H, Li A C, et al. Premedication with intravenous ketorolac trometamol (Toradol) in colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2669–2673. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison G L, Ha T V, Keblinskas D. Treatment of uterine artery vasospasm with transdermal nitroglycerin ointment during uterine artery embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:670–672. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson T. Outcome in patients undergoing unilateral uterine artery embolization for symptomatic fibroids. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel-Cox K, Jacobson G F, Armstrong M A, et al. Predictors of hysterectomy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):588.e1–5888.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampmann L E, Lohle P N, Smeets A, et al. Pain management during uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30(4):809–811. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelage J P, Guaou N G, Jha R C, et al. Uterine fibroid tumors: long-term MR imaging outcome after embolization. Radiology. 2004;230:803–809. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303030111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumori T, Kasahara T, Akazawa K. Long-term outcomes of uterine artery embolization using gelatin sponge particles alone for symptomatic fibroids. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:848–854. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies J B, Allison S, Flick P, et al. Polyvinyl alcohol particles and tris-acryl gelatin microspheres for uterine artery embolization for leiomyomas: results of a randomized comparative study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15(8):793–800. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000136982.42548.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies J B, Allsion S, Flick P, et al. Spherical polyvinyl alcohol versus tris-acryl gelatin microspheres for uterine artery embolization for leiomyomas: results of a limited randomized comparative study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16(11):1431–1437. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000179793.69590.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siskin G P, Englander M, Stainken B F, et al. Embolic agents used for uterine fibroid embolization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:767–773. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.3.1750767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasuli P, Hammond I, Al-Matairi B, et al. Spherical versus conventional polyvinyl alcohol particles for uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroencke T J, Scheurig C, Lampmann L E, et al. Acrylamido polyvinyl alcohol microspheres for uterine artery embolization: 12-month clinical and MR imaging results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu R K. Uterine artery embolization: current implications of embolic agent choice. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:1419–1422. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000190494.11439.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies J B, Spector A, Roth A R, et al. Complications after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:873–880. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J K, Sinha A S, Lumsden M A, Hickey M, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005073. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies J B. Uterine artery embolization for fibroids: understanding the technical causes of failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:11–14. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000052286.26939.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R T, Bromley P J, Pfister M E. Successful embolization of collaterals from the ovarian artery during uterine artery embolization for fibroids: a case report. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:607–610. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]