Renal ostial stenting (ROS) is the most common endovascular intervention for treatment of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. The two most common indications for ROS are refractory hypertension and progressive renal insufficiency. It is important to recognize that this intervention is most often done to mitigate either or both problems and will rarely “cure” either. ROS remains controversial with published data that both support and refute its utility. This article is the first in a two-part series dedicated to performing the “typical” procedure. The second part will deal with common problems and complications.

PREPROCEDURE

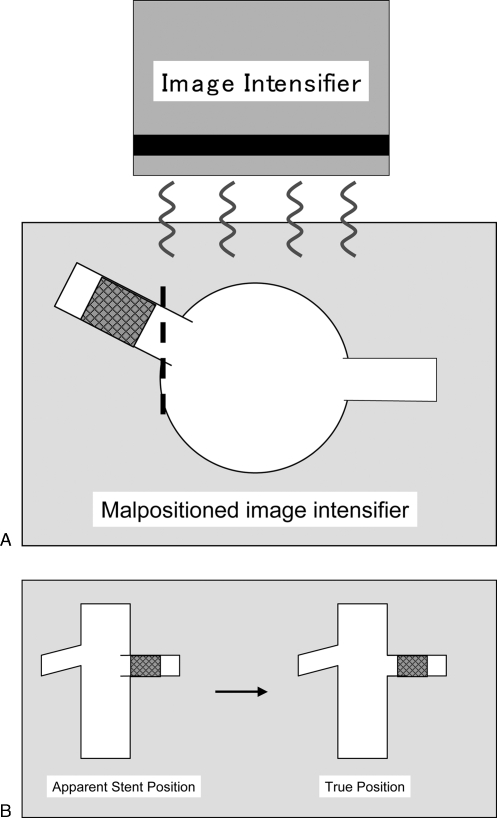

Patients should be seen in clinic. It is important that realistic expectations are set prior to initiating therapy as “cures” are the exception rather than the rule. Hypertensive patients in my practice are instructed to take one-half their usual dose of antihypertensive medications (except for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors). All patients should initiate antiplatelet therapy, either clopidogrel 75 mg per day (loading dose of 300 mg) or aspirin 81 mg per day. The renal arteries typically do not arise at a 90-degree angle from the aorta. Therefore, the image intensifier should be angled to best depict the proximal aspect of the artery in profile. Cross-sectional imaging is reviewed with particular attention to the angle of the renal arteries with respect to the aorta. This information is used to properly position the image intensifier during the procedure (Fig. 1).

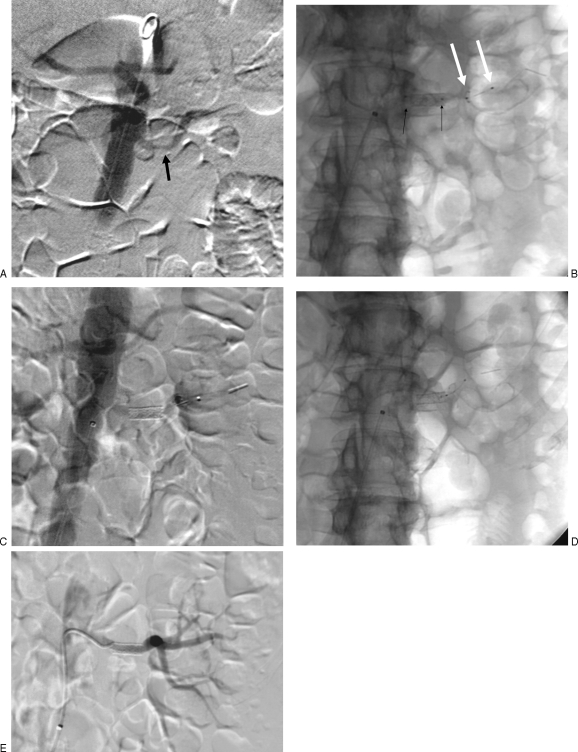

Figure 1.

Importance of image intensifier positioning. (A) Image intensifier is not orthogonal to the orifice of the renal artery. Note stent is not positioned at the ostium. (B) On fluoroscopic views, a malpositioned image intensifier may incorrectly depict the stent at the renal artery ostium when the stent is positioned too far distal in the artery.

PROCEDURE

Access

As a rule of thumb, the ipsilateral common femoral artery is punctured and a 6-French guiding sheath or sheath/guiding catheter combination is inserted. I typically use either a 30- to 45-cm-long 6-French Balkin sheath (Fig. 2) or 7-French renal guiding catheter and 7-French sheath. The sheath or guiding catheter functions as both a “backbone” to facilitate crossing tight renal artery stenoses and a port to perform contrast injections while balloons, wires, and stents are positioned across the renal artery stenosis. A brachial artery approach is sometimes necessary for severely downward-pointing renal arteries. Nonetheless, I typically start with a femoral approach initially due to the lower risk of puncture site complications and rarely (less than 5% of the time) need to use a brachial approach. The sheath is advanced into the infrarenal aorta from the femoral artery ~10 to 15 cm below the renal artery.

Figure 2.

Photograph of guiding sheath and visceral selective 1 catheter.

Renal Artery Catheterization

In patients with normal renal function, an aortogram is performed at the level of the renal arteries in the projection dictated by cross-sectional imaging to best depict the origin and proximal aspect of the artery in its entirety. The image intensifier must be orthogonal to the lesion of interest, which is usually at the origin of the renal artery. In patients with renal insufficiency, carbon dioxide may be used or aortography may be omitted altogether, especially if either computed tomographic angiography or magnetic resonance angiography is available.

CONVENTIONAL CATHETERIZATION TECHNIQUE

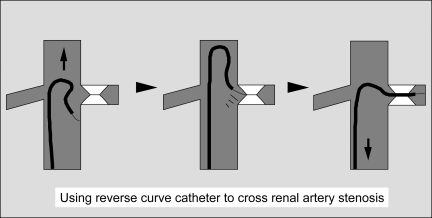

Patients should be systemically heparinized, typically with 5000 IU of heparin administered intra-arterially. Nitroglycerine in 100-μg aliquots are given intra-arterially. Note that I prefer to administer heparin prior to renal artery catheterization although some interventionalists give heparin after crossing stenoses. A short recursive catheter (e.g., visceral selective 1, Cook, Bloomington, IN) is advanced into the abdominal aorta and formed below the renal artery orifice. If this catheter does not spontaneously form in the abdominal aorta, it can be advanced into the descending thoracic aorta where it will form near the arch. Unlike longer reverse-curved catheters, such as a Simmonds 2, a short recursive catheter does not need to be formed over the aortic bifurcation or subclavian artery or by back-loading a wire with a leading suture. If formed near the arch, a soft-tipped guide wire (e.g., Bentson) is advanced out of the end of the catheter, and the catheter is retracted with the wire, leading into the infrarenal abdominal aorta. The guide wire prevents inadvertent catheterization of more proximal arteries such as spinal arteries and dragging the catheter across aortic plaques.

The catheter–guide wire combination is then advanced cephalad and pointed toward the renal artery of interest until the wire engages the orifice of the target renal artery (Fig. 3). The wire is gently rotated by the fingertips of the operator as the catheter is pulled caudal to cross the lesion. The “knee” or top curve of the catheter is positioned at the level of the renal artery orifice. The guiding sheath is then advanced close to the orifice of the renal artery to provide a “backbone” for stent insertion. The guide wire is removed, and a small volume of dilute contrast is injected into the recursive catheter to confirm intraluminal location and to exclude the possibility of renal artery dissection. Contrast injection to confirm intraluminal catheter tip position is very important and should not be omitted even if the lesion is crossed in an atraumatic fashion. If necessary, a pressure measurement can be obtained at this point, recognizing that the catheter will tend to exacerbate the degree of stenosis (i.e., if the pressure gradient is less than 5 to 10 mm Hg, it is unlikely that the lesion is hemodynamically significant).

Figure 3.

Use of reverse-curve catheter to cross tight renal artery stenosis.

A rigid, short-tipped “working wire” is advanced into the distal main renal artery. In the past, I used a 0.035-inch Rosen wire nearly exclusively, although currently, I commonly use 0.018-inch (or 0.014-inch) systems and favor a 0.018-inch McNamara wire as the working wire for most renal interventions. Irrespective of guide wire diameter, it is critically important that once selective catheterization has been achieved, the tip of the guide wire is positioned in the distal main renal artery or a proximal first- or second-order branch. It should NOT be wedged distally in the kidney as this can easily perforate the renal capsule, leading to a large perirenal hematoma, or occlude the distal vessel, causing a renal infarct.

There are advantages and disadvantages of using platforms smaller than the typical 0.035-inch ones most familiar to interventional radiologists. Occasionally, the smaller-diameter guide wires may more easily cross very tight lesions and typically enable balloon-mounted stents to be deployed without predilation. Groin complications should also be decreased because smaller-caliber sheaths and guiding catheters may be used. On the other hand, some smaller-platform angioplasty balloons are more compliant than those on 0.035-inch platform. This may predispose to incomplete stent expansion and early restenosis. Another drawback of smaller guide wires is that they do not have the same degree of “stability” compared with 0.035-inch guide wires. Thus, guiding sheaths are required in most cases.

“NO-TOUCH” TECHNIQUE

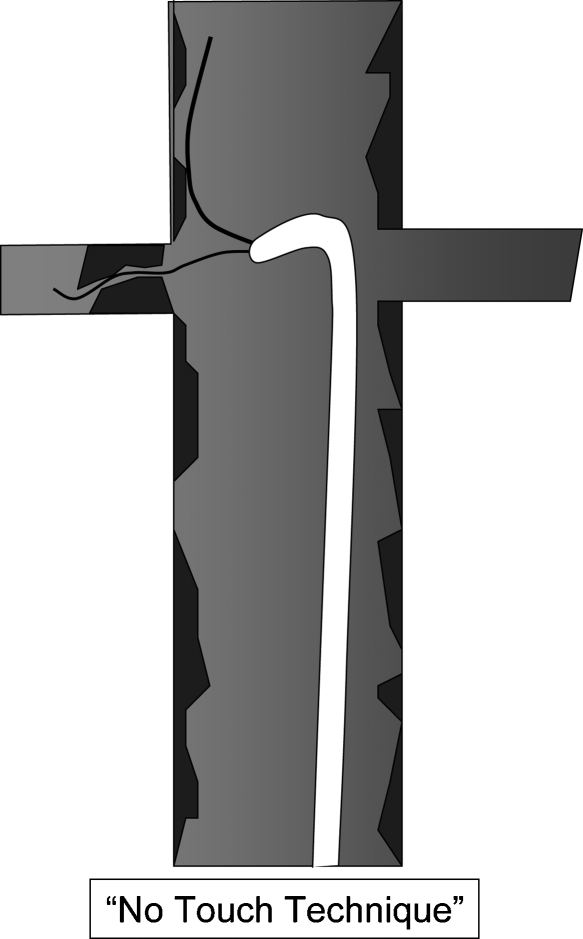

The “no-touch” procedure (Fig. 4) has been promoted as a technique to reduce catheter manipulation (with inadvertent embolization) in the aorta. This technique is similar to the one used by cardiologists during coronary interventions and refers to guide wire passage into the renal artery without direct catheterization. A 6- or 7-French guiding catheter is positioned in the aorta below the renal artery orifice with a 0.035-inch wire against the aortic wall. The purpose of this wire is to deviate the tip of the guiding catheter to prevent scraping aortic plaque and dislodging emboli. A second 0.018- or 0.014-inch wire or embolic protection device is advanced out of the sheath and used to catheterize the renal artery. In my limited experience using this technique, I have found it inferior to conventional technique with regard to caudally angulated renal arteries and in severe renal artery stenoses. It is advantageous in some cases because some embolic protection devices may be used to catheterize the renal artery (see below) without advancing a sheath into the artery (which incurs the risk of embolization).

Figure 4.

The “no-touch” technique of renal artery catheterization.

EMBOLIC PROTECTION DEVICES

There are a variety of embolic protection devices that may be used during renal stenting, although at the time this article was written, none of them were designed specifically for use in the renal artery and none are available on an 0.035-inch platform. The device chosen may alter catheterization techniques. For example, if a filter wire (Filterwire EX™ Embolic Protection System, Boston Scientific, Nattick, MA) is employed, the device is used as both a crossing wire as well as a filter basket. The device can be used with the no-touch technique (although a buddy wire is sometimes needed to cross tight lesions). One disadvantage of this device is that if conventional catheterization techniques (as described above) are utilized, a sheath or guiding catheter must be advanced across the lesion prior to deploying the basket. In my limited experience, I favor the SpideRX (ev3, Inc., Plymouth, MN) device because it enables catheterization of the renal artery with any guide wire and catheter combination prior to inserting the filter basket device.

When using the SpideRX (Fig. 5), I prefer to catheterize the renal artery using conventional technique then advance the filter wire through the recursive catheter into the distal renal artery. Alternatively, if appropriate, the recursive catheter may be exchanged for a 5-French hydrophilic catheter to enable more distal catheterization of the renal artery. The device is then advanced into the 5-French catheter via the preloaded green side of the 3.2-French catheter. (Note that the 5-French catheter may be removed over a 0.014- or 0.018-inch guide wire, and the entire device may also be advanced over this smaller wire into the distal renal artery and deployed from the green side of the prepackaged catheter.) The wire portion diameter is 0.014 inches and the catheter is a monorail system. There is a floppy ~3-cm segment of wire distal to the basket, and the basket is visible fluoroscopically between two radiopaque markers. The filter basket is deployed by simply retracting the catheter over the wire after the device is appropriately positioned. Subsequently, the catheter is removed and a 0.014-inch or 0.018-inch premounted stent or angioplasty balloon is advanced over the wire. If a monorail system is used, a portion of the wire outside of the patient can be snapped off to facilitate catheter and balloon exchanges. In my opinion, the degree of guide wire stiffness appears adequate for most renal interventions; although similar to most systems smaller that 0.035 inches, a guiding catheter may be necessary, particularly in patients with unfavorable anatomy. After dilatation, the basket is recaptured using the blue end of the catheter and removed.

Figure 5.

Dilation using the SpideRX embolic protection device. (A) Carbon dioxide angiogram shows moderate left renal artery stenosis in a patient with renal insufficiency and one kidney. (B) Fluoroscopic image shows stent dilation (black arrows, balloon; white arrows, embolic protection device). (C) Carbon dioxide angiogram after dilation shows good result. (D) Fluoroscopic image shows protection device in distal renal artery. (E.) Final digital subtraction renal angiogram using 3 mL of iso-osmolar contrast shows good result.

Stent Deployment

I stent all ostial lesions (Fig. 6). (Nonostial renal lesions are treated with angioplasty initially and stented for suboptimal results.) In the “old days,” I predilated lesions using a 4-mm angioplasty balloon catheter and advanced the guiding sheath across the plaque prior to inserting a balloon expandable mounted stent. The sheath was then retracted to expose the stent, much like deploying an inferior vena cava filter. This was done to prevent “snowplowing” the lesion and/or displacing the stent from the balloon. Currently, in my experience, the low-profile premounted monorail balloon expandable stents allow this step to be obviated in nearly all patients. By omitting the predilation and sheath insertion step, I believe the incidence of distal plaque embolization is reduced (although this is arguable). On the other hand, rarely, predilation proves difficult or impossible and alerts the operator that stent insertion should not be attempted. If the renal artery is catheterized in conventional fashion, it may be necessary to advance the sheath across the renal stenosis to use an embolic protection device such as a filter wire, if this is utilized.

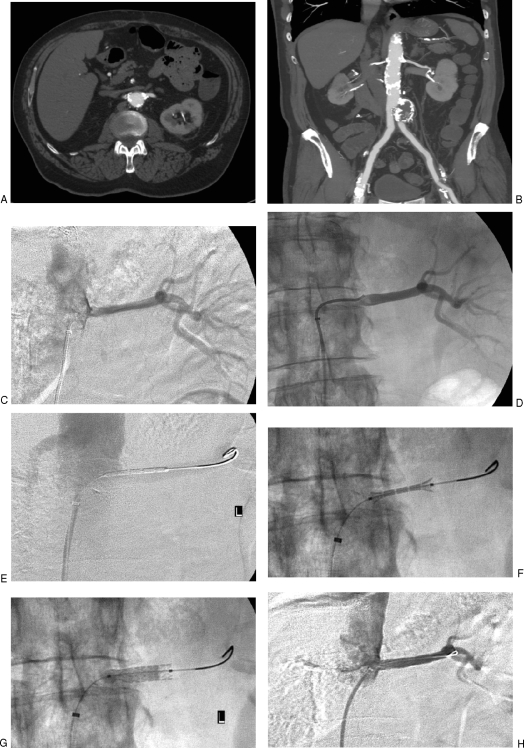

Figure 6.

Renal artery stent procedure without distal protection in a 67-year-old man with renal insufficiency. (A) Axial computed tomography (CT) image shows ostial calcification of left renal artery. (B) Coronal reformatted CT image shows atrophic right kidney and calcified left renal artery. (C) Nonselective angiogram obtained near the orifice of the left renal artery shows stenosis. (D) Angiogram obtained after crossing stenosis excluded dissection. (E) Angiogram obtained through guiding sheath shows stent positioned in the renal artery. (F) Fluoroscopic image shows balloon expandable stent being deployed. Notice “dumbbell”-shaped inflation where both ends of stent are flared before central portion is expanded, precluding stent migration. (G) Fluoroscopic image shows near-complete inflation of angioplasty balloon. (H) Final angiogram obtained through guiding sheath shows resolution of stenosis and proper stent position.

A premounted 5- or 6-mm stent (I typically use a 6 × 17-mm stent) is positioned with ~2 to 3 mm protruding into the aorta. A small amount of dilute contrast is injected into the side arm of the sheath to ensure proper positioning. The balloon is then slowly inflated to deploy the stent. Both ends of the balloon should inflate initially (the balloon looks like a dumbbell) so the stent does not migrate proximally or distally during deployment. As in all arterial dilation procedures, the guide wire must be maintained across the lesion at all times. A final angiogram is then obtained through the side arm of the sheath to assess results and exclude dissection. If results are adequate, catheters and/or protection devices are removed.

In patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis (Fig. 7), both lesions are treated during the same procedure unless an untoward event occurs during treatment of first lesion or if the procedure is unusually protracted.

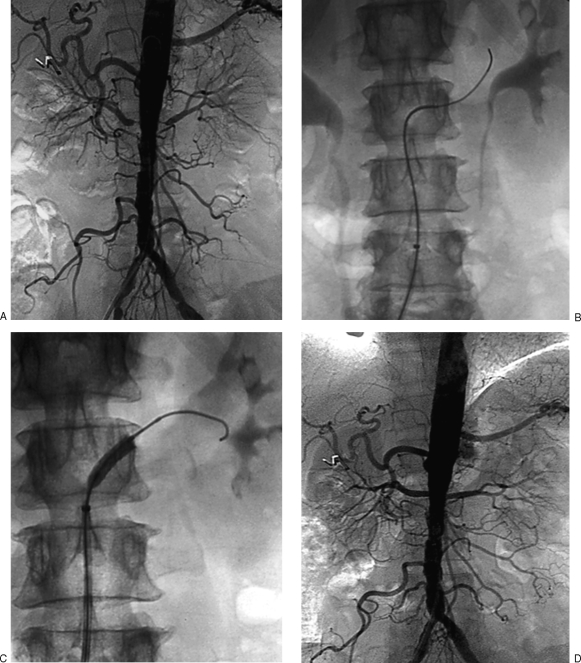

Figure 7.

Renal stenting in bilateral renal artery stenosis. (A) Aortogram shows grade bilateral ostial renal artery stenoses. (B) Fluoroscopic image demonstrates catheterization of right renal artery stenosis. (C) Fluoroscopic image shows stent deployment in right renal artery stenosis. (D) Final aortogram after treatment of both lesions shows resolution of stenoses.

POSTPROCEDURE

The sheath is removed when coagulation factors normalize or a closure device is used. I routinely admit my patients overnight and they are discharged in the morning after the procedure. They receive 3 months of clopidogrel (75 mg per day) and lifelong baby aspirin (81 mg per day).

DISCUSSION

The issue of renal angioplasty is very controversial, with skeptics noting that despite over 30 years of experience since inception, available data do not demonstrate unequivocal benefit compared with medical management. Clearly though, renal stenting can positively impact some individuals. Thus, the most difficult aspect of renovascular interventions is therefore the most basic: how do you choose the patients who are most likely to benefit from intervention? There are several factors that should be considered, but in general, in any given patient with atherosclerotic renal artery disease, there are no tests available that can accurately predict the short- or long-term benefits. Because there are no robust studies proving superiority of endovascular therapy compared with medical management, in many instances, renal revascularization for hypertension, renal salvage, or cardiac destabilization syndromes such as “flash” pulmonary edema is pursued when other etiologies have been ruled out and in patients who respond poorly to medical therapy.

The use of embolic protection devices is gaining in popularity and in my opinion will become the accepted standard of care in the immediate future. Clearly distal emboli do occur and are desirable to prevent. Although there are several studies showing that emboli are captured by protection devices, there are no comparison studies showing improvement in outcomes between protected and unprotected revascularization procedures. In the era of evidence-based medicine, some may argue that simply passing some of the devices into the distal renal artery causes more emboli than they prevent and can lead to dissection, spasm, or distal renal artery injury. Furthermore, protection devices are currently quite expensive and not designed specifically for renal intervention. Coronary devices may be undersized in some patients and cannot address emboli with early branching renal arteries. The ambitious Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions trial is ongoing and designed to compare best medical therapy with renal artery stent placement in hypertensive patients. In this trial, renal stenting is performed using embolic protection devices. The protocols are very well designed and rigorous. Hopefully, this trial will answer many questions related to renal artery stenting and once and for all establish the utility of this form of revascularization.

SUGGESTED READINGS

- Balk E, Raman G, Chung M, et al. Effectiveness of management strategies for renal artery stenosis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:901–912. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C J, Murphy T P, Matsumoto A, et al. Stent revascularization for the prevention of cardiovascular and renal events among patients with renal artery stenosis and systolic hypertension: rationale and design of the CORAL trial. Am Heart J. 2006;152:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubel G J, Murphy T P. The role of percutaneous revascularization for renal artery stenosis. Vasc Med. 2008;13:141–156. doi: 10.1177/1358863x07085408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch A T, Haskal Z J, Hertzner A R, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113:e463–e654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]