Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) insertion is among the most technically challenging procedures in interventional radiology. It combines many of the skills used in other procedures such as venous access, biopsy, angioplasty, and stent-graft insertion into one IR tour de force. A great deal of literature is devoted to patient selection, technical aspects of the procedure, and utility of the procedure in different disease processes. This article describes the technical aspects of a so-called generic TIPS procedure. I focus on an otherwise uncomplicated procedure (if that actually exists) and leave the article on tough TIPS for another issue.

PREPROCEDURE

All coagulopathies should be corrected as much as possible. As a general rule, TIPS procedures at night are unnecessary except in rare circumstances. It is my bias that most patients who will not survive the night without a TIPS will not survive long with one either. I am fortunate to be a part of a multidisciplinary liver team at my medical center; the pros and cons of TIPS are deliberated for all candidates. When I am consulted for a TIPS, there is rarely need for further discussion. Depending on your referral services, you may need to evaluate all patients carefully for indications and contraindications. All the TIPS procedures at the University of Chicago are performed with sedation managed by the department of anesthesia; most are done with general anesthesia. We have followed this algorithm since 1992 and believe the benefits far outweigh the disadvantages. When anesthesiologists handle sedation, procedural patient pain control and cooperation is optimized, unexpected problems with airway or fluid requirements are handled expeditiously, and interventional radiologists are able to focus on the task at hand.

Cross-sectional imaging should be performed and is nearly always available in 2008. Having a blueprint of the relevant anatomy eliminates surprises and allows accurate preprocedural planning. Patients with perihepatic ascites should have it drained immediately prior to the procedure. Capsular punctures are common in TIPS procedures, so eliminating the fluid surrounding the liver may limit the risk of significant perihepatic bleeding, and it prevents a firm fibrotic liver from turning away, as it were, during puncture attempts. We typically place a 5F angiographic pigtail catheter into the ascites and attach it to a vacuum suction bottle and drain between 1 to 2 L of fluid. The pigtail catheter is left in place during the procedure, which enables early recognition of extracapsular punctures (i.e., bloody ascites is aspirated).

A model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score should be calculated. Patients with scores > 25 have a dismal prognosis with a significant risk of early mortality (approximately two of three patients will not survive 3 months). This should be discussed with referring clinical service as well as during informed consent. You can access a MELD score calculator at http://www.unos.org/resources/meldpeldcalculator.asp.

CHOICE OF EQUIPMENT

Most of my experience is with a Rosch-Uchida set (Cook, Bloomington, IN), and I use it preferentially. Anecdotally, the Ring set (also made by Cook) may be helpful for particularly hard cirrhotic livers, and the Angiodynamics set (Angiodynamics, Queensbury, NY) can be helpful in patients with Budd-Chiari in whom a long tract is needed to bridge the hepatic vein and portal vein. Other must-haves include the following:

Rigid 0.035-inch guidewires (e.g., Amplatz Superstiff; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA)

Hydrophilic guidewires

Angioplasty balloons (from 4- to 12-mm diameter)

Bare and covered stents (e.g., Wallstents; Boston Scientific, and Viatorr stent grafts; Gore, Flagstaff, AZ)

Calibrated pigtail catheter

Hydrophilic 4F catheters (any shape)

Conventional 5F catheters in a variety of shapes (e.g., RC-1, Cobra, MPA, etc.)

10 to 12F long sheaths

PROCEDURE

Access Site

In my experience, both left and right internal jugular vein punctures may be used successfully for TIPS, and choice is typically personal preference. Each has advantages and disadvantages. My general preference is the right internal jugular vein ~1 cm above the clavicle—the same spot as central venous access. Higher punctures are less desirable because it is more difficult to torque the top of the sheath leftward (which is necessary to push the tip of the guiding sheath rightward for difficult punctures in patients with small cirrhotic livers). The left internal jugular vein also has both merits and drawbacks: It is generally easier to make punctures into the liver from a left-sided approach because mechanical advantage is maximized. However, once the portal vein is accessed, it is slightly more cumbersome to advance balloons, sheaths, and stents back around the curved track to the midline.

Hepatic Vein Catheterization and Venography

Essentially, all patients in my practice have had a prior computed tomography (CT) examination that should be reviewed before the procedure. This enables proper planning of access route and allows recognition of variant anatomy or pitfalls such as a large recanalized periumbilical vein. I do not routinely perform “wedged” portal venography—I have never found this practice particularly useful. It is associated with a small risk of capsular perforation, which can be fatal and (in my view) should be unnecessary in the majority of cases if a good-quality CT examination is available. In the uncommon case when it is necessary, it should be performed using carbon dioxide injected via an occlusion balloon inflated in the right hepatic artery several centimeters from the hepatic vein/inferior vena cava (IVC) confluence. The hepatic vein is catheterized to ensure patency and provides a visual landmark from which to initiate liver punctures.

Portal Vein Puncture

The curved guiding sheath is advanced into the hepatic vein orifice, turned slightly anterior, and the needle-catheter is advanced into the liver toward the portal vein. A few caveats should be remembered during this maneuver. First, punctures should be initially made from the central-most portion of the hepatic vein (i.e., near the hepatic vein confluence) rather than more peripherally because this will result is a relatively straight course for the shunt, which is usually best for long-term patency and facilitates passing balloons and stent grafts into the liver. Second, the portal triads in patients with cirrhosis are usually quite fibrotic. Therefore, you can encounter a great deal of resistance that can cause the needle-catheter combination to buckle as punctures are made. If you don't feel resistance during a needle pass in a patient with cirrhosis, it is unlikely you have entered the portal vein. Third, the curved sheath may need to be slightly wedged into the hepatic vein orifice to facilitate passage of the catheter-needle into the liver. Finally, punctures from the right hepatic vein are made anteriorly, and punctures from the middle hepatic vein are made posteriorly. It is critical to recognize which hepatic vein is catheterized.

After the needle-catheter is advanced toward the portal vein, the needle is removed, a 5-mL syringe with a 50/50 mixture of contrast and saline is attached to the hub of the catheter, and the catheter is slowly retracted while aspirating. If blood is aspirated, contrast is injected to determine what has been punctured: portal vein (good), hepatic vein (not good), or hepatic artery (bad). Hepatic vein and artery punctures usually have no adverse sequelae. Typically, the portal vein is either entered within 5 minutes (3 to 4 passes) or it takes an hour or more and 50 to 100 passes. This portion of the procedure takes luck and patience. It is important to review the CT examination again to direct punctures to the intended target. In particularly difficult cases, an assortment of maneuvers such as percutaneous portal vein localization, “gun-sight” TIPS, and intravascular ultrasound-guided direct portal vein punctures can be attempted, which are beyond the scope of this article.

Once the portal vein is entered, a portal venogram is performed to determine the entry site into the portal vein (Figs. 1A,B). Punctures into the main portal vein should be abandoned because this portion of the vein is extrahepatic.

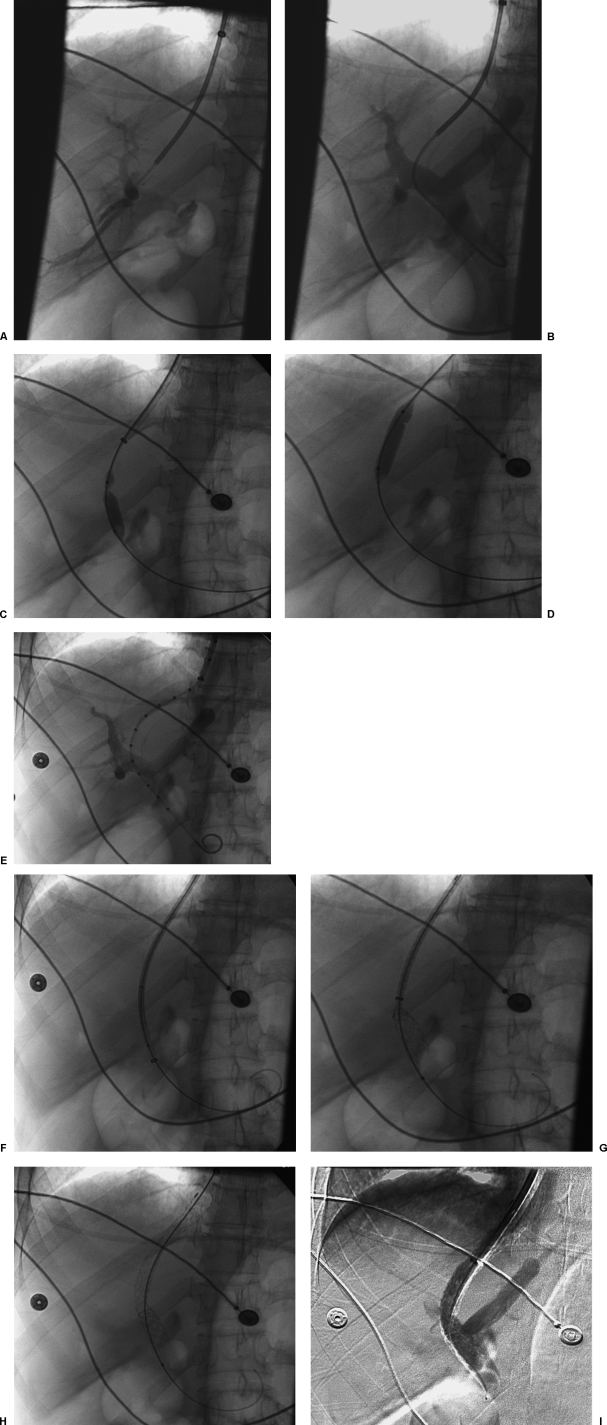

Figure 1.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure. (A) Portal venogram after successful puncture from the hepatic vein shows opacification of branches of the right portal vein. (B) Portal venogram after catheter has been advanced into the main portal vein shows normal portal vein bifurcation and intrahepatic branches. (C) Fluoroscopic image demonstrates focal waist on the angioplasty balloon indicating portal vein entry site. (D) Fluoroscopic image demonstrates focal waist on the angioplasty balloon indicating hepatic vein exit site. (E) Portal venogram using calibrated pigtail catheter to measure length of tract. (F) Fluoroscopic image shows stent graft positioned in 10F long sheath that has been advanced into the portal vein. (G) Fluoroscopic image shows deployment of the uncovered portion of the stent graft into the portal vein. (H) Fluoroscopic image demonstrates full deployment of the stent graft. (I) Digital subtraction portal venogram shows flow into the liver and through the stent graft.

Tract Dilation and Pressure Measurement

Once a suitable entry site is secured, a guidewire is advanced into the main portal vein and into either the splenic vein or superior mesenteric vein. A hydrophilic guide wire is helpful for difficult access cases, but I usually start with a Bentson wire. Portal pressure measurements are obtained and a rigid guidewire such as an Amplatz Superstiff wire is positioned with its tip in either the splenic or superior mesenteric vein. A 6- to 8-mm angioplasty balloon is then used to predilate the tract (Figs. 1C,D). If the passage of this balloon proves difficult, a smaller balloon can be chosen or the tract can be Dottered using the curved guiding sheath. This latter maneuver should be done with caution. If the puncture site is extrahepatic, this can result in portal vein laceration with catastrophic consequences. Upon dilation, two waists will be identified on the angioplasty balloon. The more cephalad waist marks the exit site of the hepatic vein, and the more caudal represents the entry site into the portal vein.

After tract predilation, a calibrated pigtail catheter is positioned into the portal vein to perform portal venography (Fig. 1E). During the angiogram, contrast material is first injected into the calibrated pigtail catheter, followed by injection of the sheath, which should be positioned at the hepatic vein/IVC orifice. The tract is then measured from portal vein entry site to the hepatic vein/IVC junction using the calibrated catheter. A Viatorr stent graft, which is 1 cm longer than the measured distance, is chosen for deployment (e.g., if the tract measures 6 cm, use a 7-cm-long stent graft). I empirically choose a 10-mm-diameter stent graft and postdilate the graft to 8 mm using an 8 mm diameter × 4 cm long angioplasty balloon catheter.

Stent Graft Deployment

The outer sheath is then advanced into the portal vein using the inner dilator portion to lead or simply advancing it over an angioplasty balloon catheter. A Viatorr stent graft is loaded into the sheath and advanced to the end of the sheath (Fig. 1F). The sheath is then retracted into the IVC while holding the stent graft in position to deploy the distal uncovered end of the device (Fig. 1G). Remember to pull the sheath all the way back into the IVC or you will risk deploying the stent graft in the sheath. The stent graft is pulled back to the entry site of the portal vein or until the end of the graft is at the desired position of the hepatic vein/IVC junction and deployed by pulling the ripcord (Fig. 1H). I postdilate the graft using an 8-mm balloon and repeat pressure measurements and venography (Fig. 1I). I stop if the gradient is ≤ 12 mm Hg. The covered end of the graft should extend to the IVC and even into the IVC slightly. Grafts that are not positioned to cover the hepatic vein completely are prone to early stenosis and occlusion (Fig. 2). As a general rule, I do not embolize varices. In the vast majority of cases, varices should not fill if the shunt is functioning adequately. If I see continued filling of varices, I redilate TIPS prior to attempting embolization with coils.

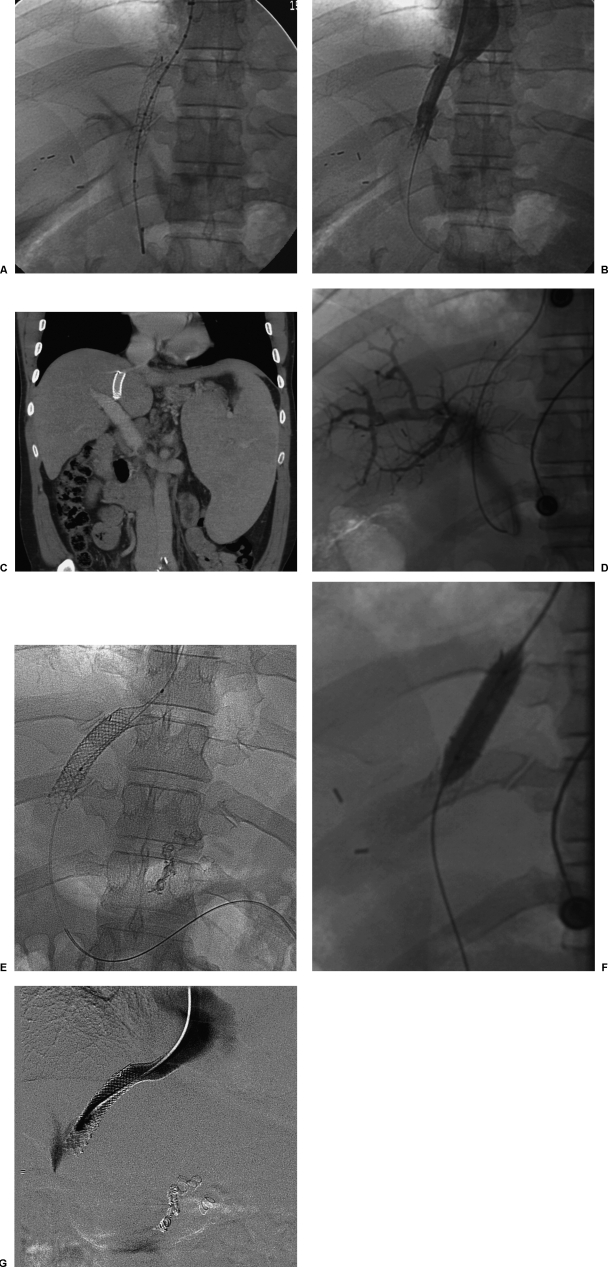

Figure 2.

Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) occlusion due to short stent-graft insertion. (A) Final fluoroscopic image shows stent graft incompletely covering hepatic vein outflow. (B) Final venogram shows patent TIPS. (C) Coronal reformatted computed tomography image shows stent graft incompletely covering hepatic vein outflow. (D) Portal venogram performed 1 year later shows TIPS occlusion. (E) Fluoroscopic image shows stent graft placed across hepatic vein outflow. (F) Fluoroscopic image shows balloon dilation of newly placed stent graft. (G) Final venogram shows wide patency of stent graft.

POSTPROCEDURE

Doppler ultrasound exam of the Viatorr stent graft cannot be performed for several days after the stent graft is inserted. This has been attributed to air that is trapped within the encapsulated layers of the device. We have stopped routinely obtaining this examination because early thrombosis is exceedingly rare with the elimination of biliary-to-TIPS fistulae. Patients are monitored overnight in the intensive care unit and transferred or discharged from the hospital as their condition permits. We obtain follow-up ultrasound examinations at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months.

DISCUSSION

TIPS has become an excellent treatment modality for several disorders including refractory variceal hemorrhage, refractory ascites, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and hepatic hydrothorax. When I trained, most of our TIPS procedures were for variceal hemorrhage unresponsive to endoscopic and medical management. This led to many procedures being performed as a last resort in less than optimal conditions. Not surprisingly, many of these patients fared poorly even with successful procedures.

In my current practice, we have increasingly used shunts for refractory ascites. This shift in practice has translated into many more elective TIPS procedures rather than emergent ones. Increasingly, randomized trials are showing the efficacy of TIPS in refractory ascites, and some have shown a survival advantage, although this topic remains controversial. In my opinion, TIPS should be the treatment of choice in patients with refractory ascites who have low MELD scores. It should be used cautiously in others, especially in those with relatively advanced liver disease.

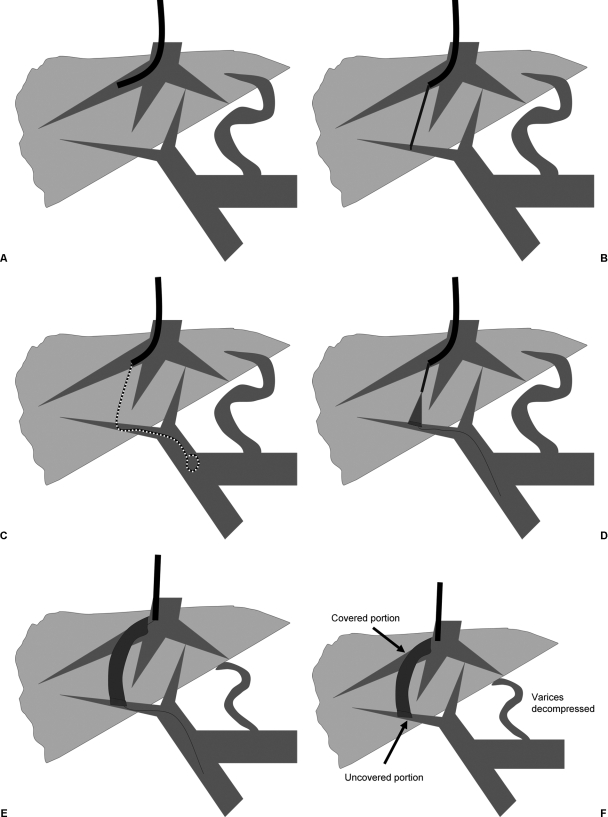

The two main limitations of TIPS have been shunt dysfunction and hepatic encephalopathy. Covered stents have helped address the first liability and improved long-term patency. Covered stents should be used routinely for all procedures (Fig. 3). Bare stents may be used when decompression of the portal system is needed urgently (e.g., active hematemesis during the procedure) because these devices are technically easier to insert relatively quickly. Hepatic encephalopathy can be managed successfully in > 90% of patients with medical therapy, but those for whom medical therapy fails have a poor prognosis.

Figure 3.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure using covered stent. (A) Right hepatic vein is catheterized. (B) Puncture is made from hepatic vein to portal vein. (C) Calibrated pigtail catheter is used to perform portal venogram and to measure length of tract. (D) Stent graft is placed positioning uncovered portion in portal vein. (E) Stent graft is fully deployed. (F) Final stent graft position with decompression of varices.