In a short time, central venous access has become a very common procedure in interventional radiology. With the aid of image guidance, interventional radiologists can quickly and safely insert a variety of venous access devices in a variety of patients. Catheter malposition has been effectively eliminated and procedural-related complications such as pneumothorax have been markedly reduced. Tunneled central venous catheter insertion is a procedure that should be in the armamentarium of all interventional radiologists.

PREPROCEDURE

Informed consent is obtained in all procedures. The most common complication associated with tunneled catheters is infection with procedural-related complications such as accidental arterial puncture, bleeding, and pneumothorax being much less likely. Sterility is mandatory for tunneled catheter insertion and all personnel follow standard surgical scrub protocol. Coagulopathies are corrected. As a lower threshold for tunneled catheter insertion, we use platelets of > 50,000 and an international normalized ratio of < 1.5. As a rule of thumb, the most common problem with tunneled catheter placement in coagulopathic patients is bleeding from the subcutaneous tunnel. Correction of underlying coagulopathies minimizes the risk of this problem. In my hospital, prophylactic preprocedural antibiotics (1 g cephazolin) are administered prior to tunneled catheter insertion unless the patient is already on antibiotics for another reason. We do not place tunneled catheters in patients with ongoing infection and positive blood cultures; instead, we will insert nontunneled catheters as needed. Conscious sedation with Fentanyl (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium) and midazolam is used in the majority of procedures.

CATHETER CHOICE

In my hospital, most tunneled central venous catheters are inserted for either dialysis or chemotherapy. It is crucial to recognize that “one size does NOT fit all” when it comes to tunneled catheters. Dialysis or plasmapheresis catheters must be relatively large bore to allow high flow rates. In contrast, catheters with smaller luminal diameters may be used for infusion (e.g., chemotherapy). The number of lumens loosely correlates to infection risk so the fewest number of lumens required for therapy should dictate catheter choice.

PUNCTURE SITE

The access site is influenced by the indication and type of catheter being inserted. Nonetheless, as a general rule, the access site of choice is nearly always the right internal jugular vein. If this vein is occluded or cannot be used for some other reason, other veins in the neck may be chosen. The Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative (http://www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guideline_upHD_PD_VA/index.html) lists the order of preference for hemodialysis. My general order preference is essentially the same: right internal jugular vein, left internal jugular vein, right external jugular vein, and left external jugular vein. The subclavian veins may or may not be appropriate for central venous access. They should be avoided in hemodialysis patients as catheter insertion is associated with central venous stenosis, which can preclude shunt creation in the ipsilateral limb. If the neck or chest has no usable veins, the femoral veins can be used or attempts at recanalization or insertion via collateral veins can be attempted. This decision is based on a multitude of factors such as expected duration of access, patient underlying condition, and so forth.

VENOPUNCTURE

The patient is prepped (scrubbed using chlorhexidine solution) and draped in the supine position and asked to turn his or her head away from the side of puncture (Fig. 1). Ultrasound-guided puncture of the jugular veins is mandatory. Using ultrasound will preclude most puncture site complications. A vein is easily distinguished from an artery in most instances as veins are easily compressible and arteries are not (Fig. 2). I use a micropuncture set (21 gauge needle, 0.018 inch guide wire, co-axial 3 and 5 French dilators) for all venous access. I attach the needle to a 10 cc syringe. It is ideal to puncture the internal jugular vein between the medial and lateral heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle ~1 cm above the clavicle. Puncturing higher than this may predispose the catheter to kinking. The probe is held in a transverse orientation and the center of the probe is positioned above the target vein, the needle is then placed on the skin at the center of the probe and advanced on the same angle as the ultrasound probe toward the vein. Subcutaneous lidocaine is used for local anesthesia. Typically, the vein will tent slightly and then the needle will pass into the vein (Fig. 3). Occasionally, through and through puncture occurs. After venopuncture, the needle is slowly withdrawn with very gentle suction on the syringe until dark red blood is aspirated. The 0.018 inch guide wire is advanced into the vein and the needle is exchanged for the co-axial dilators.

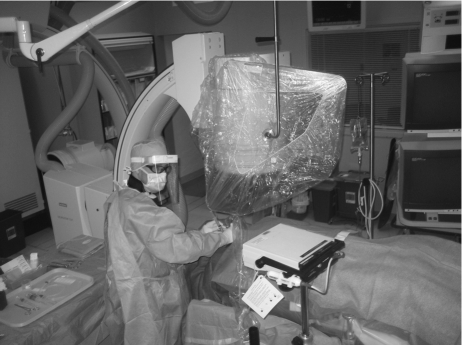

Figure 1.

Patient prep for right internal jugular vein catheter insertion.

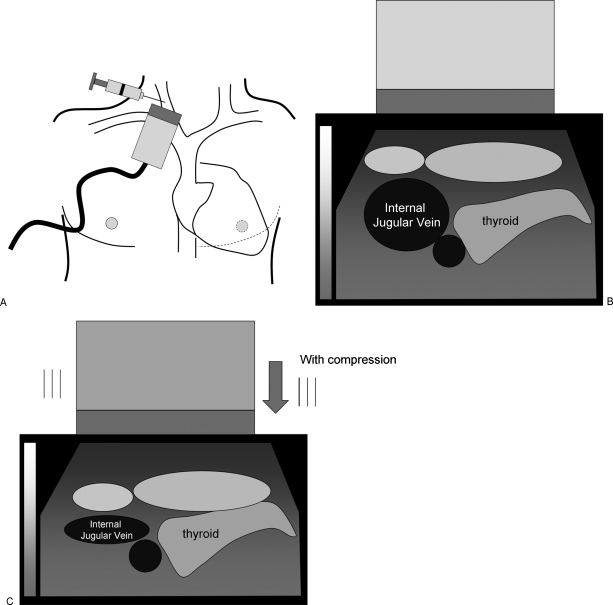

Figure 2.

Ultrasound guided puncture. (A) Ultrasound-guided puncture of right internal jugular vein. (B) Ultrasound scan of right neck over intended puncture site. (C) With compression, the internal jugular vein walls coapt whereas the carotid artery walls do not.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound guided puncture.

TUNNEL CREATION

Subcutaneous lidocaine is infiltrated along the expected course of the tunnel. As a rule of thumb, the tunnel should be at least 8 to 10 cm in length and I prefer to use a very gentle curve to minimize the risk of kinking and facilitate catheter flow rates. An #11 blade is then used to create a 5 mm incision on the chest wall at the desired entry site on the chest. A trocar included in the tunneled catheter kit is used to create a tunnel to the puncture site in the neck (Fig. 4). The puncture site is enlarged slightly (to ~5 to 10 mm) using a scalpel to enable the trocar to pass out of the skin adjacent to the venopuncture. The catheter is then attached to the trocar and pulled through the tunnel. It is best to pull the cuff of the catheter ~5 cm into the tunnel (Fig. 5). It is much easier to pull the catheter back later than advance it forward.

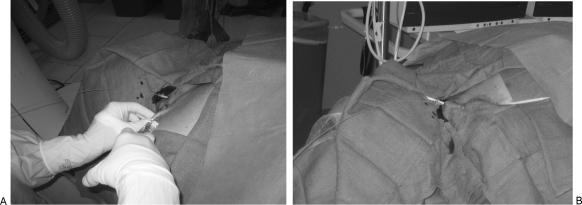

Figure 4.

Tunnel creation. (A) Local anesthetic is being infiltrated into tunnel site. (B) Plastic tunneling device passed through subcutaneous tunnel.

Figure 5.

Catheter placement via tunnel. Catheter is pulled through tunnel using tunneling device.

CATHETER PLACEMENT

Different length precut catheters are used from the right or left side. It is mandatory to recognize that different manufacturers measure the catheters differently; it is important to familiarize yourself with the nomenclature of the particular catheter you are using. Catheters that are not precut are trimmed to appropriate length at the time of procedure.

A 0.035 inch rigid guide wire (e.g., Amplatz super stiff; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) is placed with its distal tip in the interior vena cava. In my opinion, this step will nearly completely obviate the risk of great vessel laceration. This catastrophic complication usually occurs during left-sided catheter insertion when the peel-away sheath is advanced from the puncture site into the vein over a relatively floppy guide wire.

The coaxial micropuncture set dilators are exchanged over the rigid wire for the peel-away sheath (Fig. 6). A slight twist at the skin with firm, constant forward pressure will enable the sheath to be advanced into the vein. Occasionally, predilation with a smaller caliber dilator will facilitate this maneuver. The guide wire and dilator are removed and the catheter is inserted as far as possible into the sheath and vein. The sheath is then slowly peeled apart while the catheter is held in position. Usually after the sheath is peeled apart, the catheter needs to be retracted slightly to clear any kinks. The tip should be at the cavoatrial junction or within the right atrium.

Figure 6.

Final catheter insertion. (A) Peel-away sheath advanced to puncture site. (B) Catheter advanced into peel-away sheath after dilator has been removed. (C) Final catheter position after sheath has been peeled away.

The catheter is then sutured to the skin and the incision site in the neck is closed. The ports of the catheter are flushed with saline. Both ports are aspirated with a 10 cc syringe to ensure good blood flow and then loaded with heparin. A completion fluoroscopic image is then obtained; we do not perform postprocedure chest radiography.

DISCUSSION

Central venous access was first performed by radiologists in our hospital in 1995 and since that time we have assumed many of the procedures that had previously been done in the operating rooms. The rate of all procedure-related complications has dropped dramatically with image-guided insertion. Arterial hematomas, pneumothoraces, and catheter malpositioning are virtually nonexistent with image-guided insertion.

Several common pitfalls are encountered when placing central lines. The majority occurs early in one's experience and a few are catastrophic:

Contamination during the procedure. Contamination can occur from a variety of sources including inadequate draping, patient movement during the procedure, or inadvertently allowing a guide wire or catheter to contact something outside the sterile field.

Inability to gain venous access. This usually results in patients with prior catheters when the vein is either occluded or stenotic. It may be very difficult to advance the 0.018 inch guide wire through the 21 gauge needle. Manipulation at the puncture site can lead to kinking the wire—if this occurs, the needle and wire must be removed as a unit or the wire tip can be sheared off in the patient. At times, it is helpful to advance the 3 French dilator over the wire alone and subsequently use a different 0.018 inch wire (e.g., V18 control wire; Boston Scientific) to negotiate stenoses or venous occlusions. Additionally, venography can be performed using the 3 French dilator to better define abnormal anatomy.

Catheter kinking. This problem typically results when the incision site in the neck is too short or too superficial leaving a tag of tissue between the catheter and vein entry site. To alleviate the problem, blunt dissection is used to remove the tag.

Venous laceration. This catastrophe usually occurs when the peel-away sheath-dilator combination is advanced over a relatively floppy guide wire through the vein. Alternatively, a rigid guide wire may not be in the inferior vena cava. The wire-dilator tandem punctures the wall of the vein. It is important to position the tip of the rigid wire in the inferior vena cava; this will prevent this complication in the vast majority of cases. This complication has been discussed in detail in a prior issue (Semin Intervent Radiol 2006;23:114–116).

Difficulty advancing catheter through sheath. This challenge usually occurs when the peel-away sheath is kinked at a vessel bifurcation. Most commonly it occurs from a left-side approach when the sheath tip is kinked at the junction of the left brachiocephalic vein and left internal jugular vein. Occasionally, it is crimped in the neck if the incision site is too small or there is abundant scar tissue from previous catheterization. Advancing a hydrophilic guide wire into the catheter under fluoroscopic guidance reinforces the catheter enabling it to be advanced more easily.

Accidental arterial puncture. Inadvertent arterial puncture typically occurs in patients with a history of prior catheterization when jugular veins are quite small in caliber or occluded altogether. If recognized, the needle can be removed and the puncture site compressed for several minutes. In the rare instance that it is unrecognized, and catheter insertion has been performed, the catheter should be removed surgically.

SUGGESTED READINGS

- Ray C E. Central Venous Access. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001.

- Funaki B. Central venous access: a primer for the diagnostic radiologist. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:309–318. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.2.1790309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Kidney Foundation 2006 Update on Hemodialysis Adequacy. Available at: http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_updates/doqi-uptoc.html. Accessed October 31, 2008. Available at: http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_updates/doqi-uptoc.html