Abstract

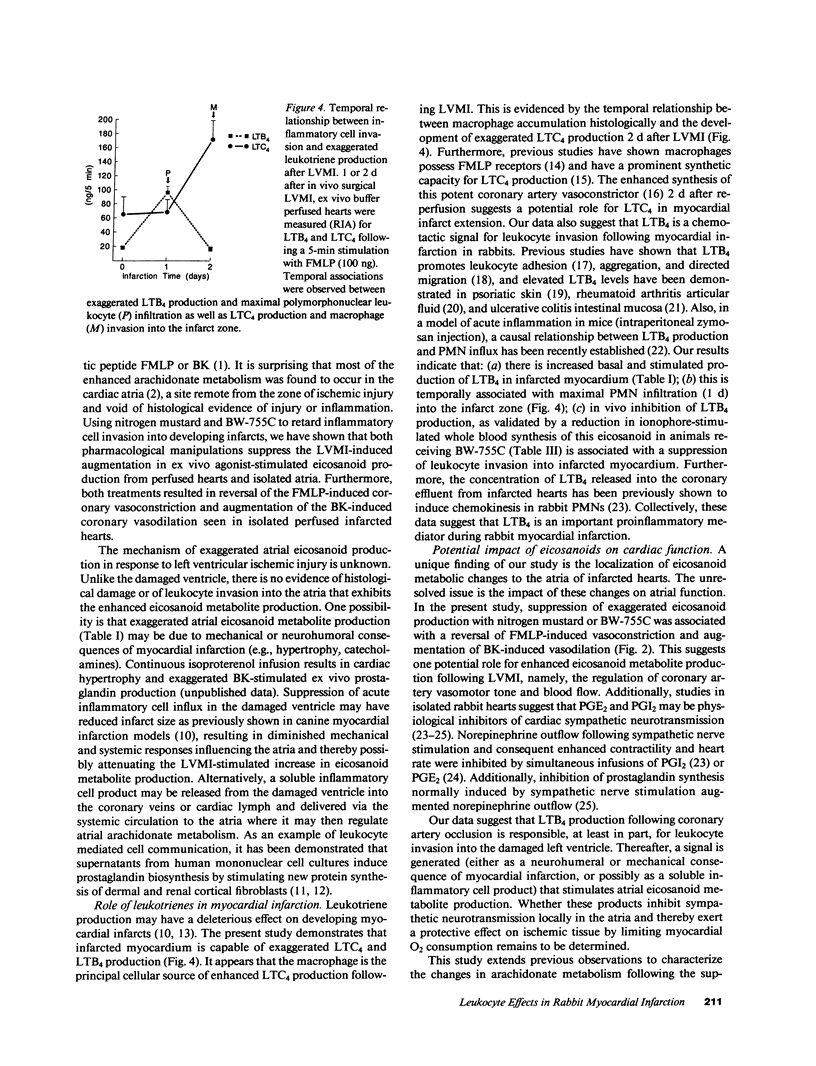

The isolated perfused hearts of rabbits previously subjected to in vivo left ventricular myocardial infarction (LVMI) show a 5-10-fold increase in f-Met-Leu-Phe (FMLP) and bradykinin (BK)-stimulated eicosanoid metabolite production relative to noninfarcted hearts. This exaggerated arachidonate metabolism has been shown to occur primarily in the cardiac atria, a site remote from the zone of injury and to be associated with a 10-15-fold increase in atrial FMLP receptor number in the absence of atrial inflammation. All of these changes were temporally related to leukocyte infiltration into the infarct zone. To determine whether invading leukocytes mediate these responses, acute inflammatory cell influx was suppressed either by inducing leukopenia with nitrogen mustard or by administration of BW-755C, a mixed cyclooxygenase-lipoxygenase inhibitor. Both pharmacological manipulations resulted in a decrease in inflammatory cells in the infarct zone and a marked suppression (50-70%) of ex vivo agonist-stimulated eicosanoid metabolite production from perfused hearts and isolated atria. These manipulations also resulted in reversal of ex vivo FMLP-induced coronary vasoconstriction as well as augmentation of BK-induced coronary vasodilation. Further studies in nitrogen mustard-treated animals revealed a suppression of the LVMI-stimulated increase in atrial FMLP receptor number. These data show that suppression of leukocyte invasion after LVMI attenuates enhanced cardiac and atrial eicosanoid metabolite production, and results in marked changes in coronary vascular reactivity. An additional finding was that basal and stimulated LTB4 production was markedly increased in infarcted hearts. In vivo suppression of the increase in LTB4 production by BW-755C was associated with inhibition of inflammatory cell influx into the infarct zone. It therefore appears that LTB4 may be an important proinflammatory mediator of leukocyte invasion after LVMI.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bonow R. O., Lipson L. C., Sheehan F. H., Capurro N. L., Isner J. M., Roberts W. C., Goldstein R. E., Epstein S. E. Lack of effect of aspirin on myocardial infarct size in the dog. Am J Cardiol. 1981 Feb;47(2):258–264. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain S., Camp R., Dowd P., Black A. K., Greaves M. The release of leukotriene B4-like material in biologically active amounts from the lesional skin of patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1984 Jul;83(1):70–73. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12261712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray M. A., Ford-Hutchinson A. W., Smith M. J. Leukotriene B4: an inflammatory mediator in vivo. Prostaglandins. 1981 Aug;22(2):213–222. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(81)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. M., Rae S. A., Smith M. J. Leukotriene B4, a mediator of inflammation present in synovial fluid in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1983 Dec;42(6):677–679. doi: 10.1136/ard.42.6.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers A. S., Dunkel C. G., Saffitz J. E., Needleman P. Exaggerated atrial arachidonate metabolism in rabbit left ventricular myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 1987 Jan;79(1):155–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI112777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers A. S., Murphree S., Saffitz J. E., Jakschik B. A., Needleman P. Effects of endogenously produced leukotrienes, thromboxane, and prostaglandins on coronary vascular resistance in rabbit myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 1985 Mar;75(3):992–999. doi: 10.1172/JCI111801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedqvist P., Wennmalm A. Comparison of the effects of prostaglandins E 1, E 2 and F 2 alpha on the sympathetically stimulated rabbit heart. Acta Physiol Scand. 1971 Oct;83(2):156–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1971.tb05064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly S. R., Lucchesi B. R. Effect of BW755C in an occlusion-reperfusion model of ischemic myocardial injury. Am Heart J. 1983 Jul;106(1 Pt 1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn J. H., Halushka P. V., LeRoy E. C. Mononuclear cell modulation of connective tissue function: suppression of fibroblast growth by stimulation of endogenous prostaglandin production. J Clin Invest. 1980 Feb;65(2):543–554. doi: 10.1172/JCI109698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowith J. B. Essential fatty acid deficiency inhibits the in vivo generation of leukotriene B4 and suppresses levels of resident and elicited leukocytes in acute inflammation. J Immunol. 1988 Jan 1;140(1):228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowith J. B., Jakschik B. A., Stahl P., Needleman P. Metabolic and functional alterations in macrophages induced by essential fatty acid deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 15;262(14):6668–6675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowith J. B., Okegawa T., DeSchryver-Kecskemeti K., Needleman P. Macrophage-dependent arachidonate metabolism in hydronephrosis. Kidney Int. 1984 Jul;26(1):10–17. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclouf J., Pradel M., Pradelles P., Dray F. 125I derivatives of prostaglandins. A novel approach in prostaglandin analysis by radioimmunoassay. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976 Apr 22;431(1):139–146. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(76)90268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullane K. M., Read N., Salmon J. A., Moncada S. Role of leukocytes in acute myocardial infarction in anesthetized dogs: relationship to myocardial salvage by anti-inflammatory drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984 Feb;228(2):510–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okegawa T., Jonas P. E., DeSchryver K., Kawasaki A., Needleman P. Metabolic and cellular alterations underlying the exaggerated renal prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis in ureter obstruction in rabbits. Inflammatory response involving fibroblasts and mononuclear cells. J Clin Invest. 1983 Jan;71(1):81–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI110754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer R. M., Stepney R. J., Higgs G. A., Eakins K. E. Chemokinetic activity of arachidonic and lipoxygenase products on leuocyctes of different species. Prostaglandins. 1980 Aug;20(2):411–418. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(80)80058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reingold D. F., Watters K., Holmberg S., Needleman P. Differential biosynthesis of prostaglandins by hydronephrotic rabbit and cat kidneys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981 Mar;216(3):510–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson B., Wennmalm A. Increased nerve stimulation induced release of noradrenaline from the rabbit heart after inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. Acta Physiol Scand. 1971 Oct;83(2):163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1971.tb05065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon P., Stenson W. F. Enhanced synthesis of leukotriene B4 by colonic mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1984 Mar;86(3):453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyderman R., Fudman E. J. Demonstration of a chemotactic factor receptor on macrophages. J Immunol. 1980 Jun;124(6):2754–2757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaethe S. M., Freed M. S., De Schryver-Kecskemeti K., Lefkowith J. B., Needleman P. Essential fatty acid deficiency reduces the inflammatory cell invasion in rabbit hydronephrosis resulting in suppression of the exaggerated eicosanoid production. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988 Jun;245(3):1088–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoike H., Egashira K., Yamada A., Hayashi Y., Nakamura M. Leukotriene C4- and D4-induced diffuse peripheral constriction of swine coronary artery accompanied by ST elevation on the electrocardiogram: angiographic analysis. Circulation. 1987 Aug;76(2):480–487. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.2.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennmalm M., FitzGerald G. A., Wennmalm A. Prostacyclin as neuromodulator in the sympathetically stimulated rabbit heart. Prostaglandins. 1987 May;33(5):675–691. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(87)90034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley P. J., Needleman P. Mechanism of enhanced fibroblast arachidonic acid metabolism by mononuclear cell factor. J Clin Invest. 1984 Dec;74(6):2249–2253. doi: 10.1172/JCI111651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. D., Robin J. L., Lewis R. A., Lee T. H., Austen K. F. Generation of leukotrienes by human monocytes pretreated with cytochalasin B and stimulated with formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine. J Immunol. 1986 Jan;136(2):642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]