Abstract

To assess the prevalence of improperly discarded syringes and to examine syringe disposal practices of injection drug users (IDUs) in San Francisco, we visually inspected 1000 random city blocks and conducted a survey of 602 IDUs. We found 20 syringes on the streets we inspected. IDUs reported disposing of 13% of syringes improperly. In multivariate analysis, obtaining syringes from syringe exchange programs was found to be protective against improper disposal, and injecting in public places was predictive of improper disposal. Few syringes posed a public health threat.

Needlestick injuries resulting from injection drug users (IDUs) improperly disposing of syringes present a potential risk of transmission of viral infections such as hepatitis and HIV to community members, sanitation workers, law enforcement officers, and hospital workers.1–8 There have been no reports of HIV, HBV, or HCV seroconversion among children who incurred accidental needlesticks.6,7,9–11 Among IDUs, syringe exchange program (SEP) utilization is associated with proper disposal of used syringes.12–16 In 2007, the San Francisco Chronicle published a series of articles containing anecdotal reports of widespread improper disposal of syringes on city streets and in Golden Gate Park. The reports implied that SEPs were responsible for improper disposal of syringes.17–19 Concerned about public safety, the San Francisco Department of Public Health worked with other researchers to (1) determine the prevalence of improperly discarded syringes in San Francisco, and (2) examine syringe disposal practices of IDUs.

METHODS

We used geographic information system (GIS) software20 to map city blocks in the 11 San Francisco neighborhoods most heavily trafficked by IDUs, as determined on the basis of drug treatment and arrest data. Of the 2114 total city blocks in these 11 neighborhoods, 1000 were randomly selected for visual inspection to look for improperly discarded syringes. We extrapolated from the number of syringes found in the 1000 randomly selected blocks to estimate the total number of syringes in these 11 neighborhoods. Half of Golden Gate Park was also randomized and inspected, along with all 20 operational public self-cleaning toilets in San Francisco. A research assistant walked through each selected geographic area once from February 2008 through June 2008, visually inspecting all publicly accessible areas, including sidewalks, gutters, and grassy areas, for evidence of discarded syringes.

To examine syringe disposal practices, we conducted a quantitative survey on syringe disposal practices with 602 IDUs from January 2008 through November 2008. We used targeted sampling methods to recruit the IDUs.21,22 The main outcome variable was improper disposal of a syringe, defined as disposal in or on a street, sidewalk, park, parking lot, trash receptacle, toilet, sewer, or manhole. We used the Mantel–Haenszel χ2 statistic to determine statistical significance (α < .05) in bivariate analysis and logistic regression for multivariate analysis, using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) software version 9.13.

RESULTS

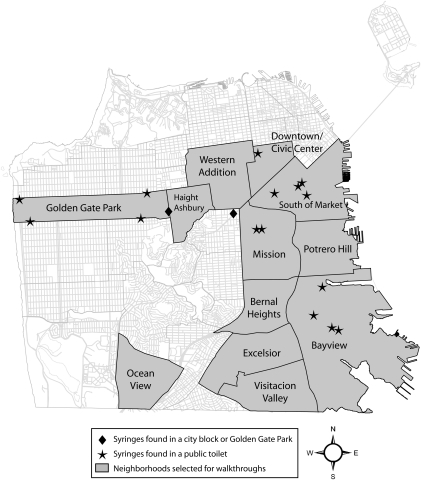

Twenty syringes were found during the visual inspection: 11 in the randomly selected blocks, 6 in Golden Gate Park, and 3 in the self-cleaning public toilets (Figure 1). By extrapolation, we estimated that there were a total of 108 improperly disposed syringes in the selected high-drug-use areas (93 on street blocks, 12 in Golden Gate Park, and 3 in public toilets). In none of the found syringes was there visible blood or an exposed needle; 5 of the syringes were capped, and the other 15 had the needle broken off. The majority of found syringes, although visible, were not easily accessible (e.g., behind a fence, in the gutter).

FIGURE 1.

Locations of syringes found in selected neighborhoods (n = 20): San Franscisco, CA, March 2008–June 2008.

In the survey, 67% of IDUs reported improper disposal at some point over the prior 30 days (Table 1), with 13% (8425 of 66 409) of syringes being disposed of improperly. Eighty percent of syringes were disposed of at SEPs.

TABLE 1.

Syringe Disposal Methods and Syringe Sources Among Injection Drug Users (n = 602): San Francisco, CA, 2008

| Disposal Methods and Syringe Sources | % |

| Syringe disposal methods, prior 6 mo | |

| Syringe exchange program | 62 |

| Trash | 53 |

| Flushing down the toilet | 15 |

| Giving them away | 12 |

| Hospital/clinic | 11 |

| Public place | 11 |

| Police confiscation | 8 |

| Public disposal box | 8 |

| Sewer/manhole | 4 |

| Selling | 4 |

| Private disposal box | 3 |

| Pharmacy | 1 |

| Any improper syringe disposal methods in prior 30 da | 67 |

| Syringe sources, prior 6 mo | |

| Syringe exchange program | 83 |

| Someone else who goes to syringe exchange program | 52 |

| Pharmacy purchase | 33 |

| Purchase from an unauthorized sourceb | 34 |

In a public place, in the trash, down the toilet, or in a sewer or manhole. The percentage of syringes disposed of improperly was 13% (8425 of 66 409).

From a stranger on the street or a drug dealer.

In multivariate analysis, improper syringe dispsal was independently associated with having injected in a public place (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.6, 3.6), having injected crack in the prior 30 days (AOR = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.0, 3.5), and having obtained syringes from an unauthorized source (AOR = 3.0; 95% CI = 1.9, 4.7). Having obtained syringes from an SEP was independently protective against improper syringe disposal (AOR = 0.20; 95% CI = 0.10, 0.40).

DISCUSSION

As far as we know, this is the first study to use GIS methods to map, systematically inspect, and document the occurrence of improperly discarded syringes in public places. The number of syringes found was very small relative to the estimated 16 789 IDUs in San Francisco.23 The potential danger posed by found syringes was low, with none being able to produce a needlestick without substantial handling. A substantial proportion of IDUs reported disposing of syringes improperly at some point in the prior 30 days. However, the proportion of syringes disposed of improperly was small.

A limitation of this study is the lack of visual inspection of all city blocks in San Francisco. Thus, it is possible that we missed areas where improper disposals were more frequent. However, we did inspect nearly half the blocks (1000/2114) in the 11 neighborhoods where drug-related arrests and drug treatment admissions were highest. Another limitation is that survey data were self-reported and thus subject to recall and social desirability biases. Finally, a significant proportion of study participants reported flushing syringes down the toilet and throwing them in the trash. We were unable to assess the risk these disposal methods posed to plumbers and sanitation workers.

This study addresses a complex social problem at the intersection of public health and public opinion. Findings demonstrate that SEPs benefit the community by collecting the vast majority of potentially infectious syringes from IDUs. Structural solutions to the remaining improper disposals of syringes include lengthening SEPs' hours of operation, installing public disposal boxes,24 promoting pharmacy-based disposal,25 and providing spaces for IDUs to inject safely.26

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the San Francisco Department of Public Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01 DA021627-01A1).

We would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the study: Cindy Changar, Megan Dunbar, Allison Futeral, Alix Lutnick, Askia Muhammad, Israel Nieves-Rivera, Noah Gaiser, Jeffery Schonberg, Susan Sherman, and Michele Thorsen.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review board of RTI International.

References

- 1.Alter MJ. Occupational exposure to hepatitis C virus: a dilemma. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15(12):742–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dierks D, Miller D. Community sharps disposal program in Council Bluffs, Iowa. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2002;42(6, suppl. 2):S117–S118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drda B, Gomez J, Conroy R, Seid M, Michaels J. San Francisco Safe Needle Disposal Program, 1991–2001. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2002;42(6, suppl 2):S115–S116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanrahan A, Reutter L. A critical review of the literature on sharps injuries: epidemiology, management of exposures and prevention. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(1):144–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawitts S. Needle sightings and on-the-job needle-stick injuries among New York City Department of Sanitation workers. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2002;42(6, suppl 2):S92–S93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papenburg J, Blais D, Moore D, et al. Pediatric injuries from needles discarded in the community: epidemiology and risk of seroconversion. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e487–e492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell FM, Nash MC. A prospective study of children with community-acquired needlestick injuries in Melbourne. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38(3):322–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorentz J, Hill L, Samimi B. Occupational needlestick injuries in a metropolitan police force. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(2):146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyatt JP, Robertson CE, Scobie WG. Out of hospital needlestick injuries. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70(3):245–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makwana N, Riordan FA. Prospective study of community needlestick injuries. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(5):523–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nourse CB, Charles CA, McKay M, Keenan P, Butler KM. Childhood needlestick injuries in the Dublin metropolitan area. Ir Med J. 1997;90(2):66–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bluthenthal RN, Anderson R, Flynn NM, Kral AH. Higher syringe coverage is associated with lower odds of HIV risk and does not increase unsafe syringe disposal among syringe exchange program clients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(2–3):214–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffin PO, Latka MH, Latkin C, et al. Safe syringe disposal is related to safe syringe access among HIV-positive injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(5):652–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman SG, Rusch M, Golub ET. Correlates of safe syringe acquisition and disposal practices among young IDUs: broadening our notion of risk. J Drug Issues. 2004;34(4):895–912 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Vlahov D, et al. Discarded needles do not increase soon after the opening of a needle exchange program. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(8):730–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doherty MC, Junge B, Rathouz P, Garfein RS, Riley E, Vlahov D. The effect of a needle exchange program on numbers of discarded needles: a 2-year follow-up. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(6):936–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matier P, Ross A. The situation at Golden Gate Park. San Francisco Chronicle. July 29, 2007. Available at: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2007/07/29/BAG37R934A1.DTL. Accessed February 18, 2009

- 18.Nevius CW. Golden Gate Park sweep—can city make it stick? San Francisco Chronicle. August 2, 2007. Available at: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2007/08/02/MNTQRBGEL2.DTL. Accessed February 18, 2009

- 19.Nevius CW. On San Franciso: Golden Gate Park mess—a one-month checkup. San Francisco Chronicle. August 21, 2007. Available at: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2007/08/21/MNMCRM499.DTL. Accessed February 18, 2009

- 20.ArcGIS Software [computer program]. Version 9.9. Redlands, CA: ESRI; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bluthenthal RN, Watters JK. Multimethod research from targeted sampling to HIV risk environments. NIDA Res Monogr. 1995;157:212–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1989;36:416–430 [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFarland W. Proposed 2006 HIV consensus estimates. Paper presented at: HIV Prevention Planning Council, 2006 Full Council Meeting; April 13, 2006; San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley E, Beilenson P, Vlahov D, et al. Operation Red Box: a pilot project of needle and syringe drop boxes for injection drug users in East Baltimore. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18(suppl 1):S120–S125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golub ET, Bareta JC, Mehta SH, McCall LD, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Correlates of unsafe syringe acquisition and disposal among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(12):1751–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, et al. Changes in public order after the opening of a medically supervised safer injecting facility for illicit injection drug users. CMAJ. 2004;171(7):731–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]