Abstract

Objectives. We assessed whether associations between education and 2 health behaviors—smoking and leisure-time physical inactivity (LTPI)—depended on nativity and age at immigration among Hispanic and Asian young adults.

Methods. Data came from the 2000–2008 National Health Interview Survey. The sample included 13 345 Hispanics and 2528 Asians aged 18 to 30 years. Variables for smoking and LTPI were based on self-reported data. We used logistic regression to examine education differentials in these behaviors by nativity and age at immigration.

Results. The association of education with both smoking and LTPI was weaker for foreign-born Hispanics than for US-born Hispanics but did not vary by nativity for Asians. Education associations for smoking and LTPI among foreign-born Hispanics who had immigrated at an early age more closely resembled those of US-born Hispanics than did education associations among foreign-born Hispanics who had immigrated at an older age. A similar pattern for smoking was evident among Asians.

Conclusions. Health-promotion efforts aimed at reducing disparities in key health behaviors among Hispanic and Asian young adults should take into account country of residence in childhood and adolescence as well as nativity.

An extensive literature has established the existence of a social gradient in health, whereby health improves with each increment in socioeconomic status (SES).1,2 Although most health outcomes show social gradients, research has increasingly suggested that SES may not have the same effect on health for all US populations.3–6 In particular, researchers have found more modest socioeconomic differentials in health outcomes and related health behaviors for foreign-born populations than for corresponding US-born populations.4,5,7

One explanation for this pattern proposes that weaker social gradients in health and health behaviors among the foreign-born are rooted in lifestyle-related norms and practices in sending countries for US immigration, which may continue to shape outcomes along socioeconomic lines after arrival.4 We sought to extend the research in this area by assessing whether the relationship between education and some health behaviors depends not only on nativity but also on country of residence during childhood and adolescence. Although a recent study found that the association between subjective social status and mood dysfunction among Asian immigrants varied by age at immigration,6 to our knowledge no research has examined patterns for objective measures of SES and health behaviors. The results of this analysis may improve understanding of differences between social gradients in health behaviors in US populations and may inform efforts to target interventions to groups at higher risk for unhealthy practices.

Our conceptual framework is informed by several areas of research. Numerous studies suggest that some health behaviors, such as smoking, are heavily influenced by early life experiences.8–10 In addition, disparities in some health behaviors begin to form in childhood and adolescence, both within and outside the United States.10–13 Mechanisms that shape health behaviors by SES (e.g., access to and affordability of unhealthy lifestyles among individuals with lower versus higher SES, variation in norms and sanctions surrounding particular practices by SES) may operate differently in the sending countries for US immigration. Finally, research on acculturation suggests that as immigrants enter new contexts, their health behaviors shift toward patterns observed among native-born populations, a process that may be especially influential during childhood and adolescence.14–17 Although these changes may affect immigrants across the socioeconomic spectrum, they may also vary by SES if young immigrants adopt the health behaviors of native-born youths with similar socioeconomic backgrounds.

We focused our analysis on education gradients in smoking and leisure-time physical inactivity (LTPI). The identification of consistencies in the influence of education, nativity, and age at immigration across health behaviors may inform a more comprehensive approach to addressing disparities. We selected these behaviors for study because of their associations with education and nativity and because both are shaped in part by mechanisms operating during childhood and adolescence.11,18–20 Additionally, smoking and physical inactivity are among the leading actual causes of death in the United States.21

We examined associations between these health behaviors and education, rather than income or occupational status, because education may better represent SES for individuals who do not work consistently in the paid workforce, an issue that is particularly relevant for immigrant populations.5,22,23 Education also provides an indicator of the family socioeconomic environment during childhood and adolescence. We focused on young adults (aged 18–30 years) partly because of limitations on data available to determine age at immigration (explained in detail in the Methods section). However, patterns in young adulthood may provide insights into patterns for related health outcomes in older populations.

We first determined whether differences in education gradients in smoking and LTPI by nativity (documented for adults of all ages) were evident among young adults.4,5 If education gradients in smoking and LTPI are influenced by exposures in early life, then variation by nativity should be evident by young adulthood. Second, and more important, we investigated whether associations between education and both smoking and LTPI among foreign-born young adults who immigrated in childhood or adolescence more closely resembled associations among the US-born than was the case for the foreign-born who immigrated after adolescence. We focused on Hispanics and Asians because these groups include large immigrant populations. Finally, we assessed whether patterns varied by Hispanic and Asian subgroup and by gender.

METHODS

Data came from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a nationally representative annual survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population in the United States. The survey follows a stratified, multistage probability design.24 We combined data from 2000 to 2008 to generate a sample size sufficient to accommodate education interactions with nativity, age at immigration, racial/ethnic subgroup, and gender. The survey randomly selected 1 adult for interview from each sampled family. Response rates among eligible adults ranged from 74% to 88%. All information was self-reported.

The sample comprised 13 345 Hispanics (6295 US-born and 7050 foreign-born) and 2528 Asians (739 US-born and 1789 foreign-born) aged 18 to 30 years, for a total sample population of 15 873. Hispanic subgroups included Mexican, Central/South American, Puerto Rican, and other/multiple Hispanic. Asian subgroups included Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, and other/multiple Asian. Sample sizes for subgroups are listed in Table 1. Individuals missing information on study variables were excluded (less than 3% for any variable).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Hispanics and Asians Aged 18–30 Years (n = 15 873): National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2000–2008

| Hispanics |

Asians |

|||||||

| Foreign-Born |

Foreign-Born |

|||||||

| US-born | All | Immigrated ≤ Age 15 Years | Immigrated > Age 15 Years | US-born | All | Immigrated ≤ Age 15 Years | Immigrated > Age 15 Years | |

| No. (unweighted) | 6295 | 7050 | 2918 | 4132 | 739 | 1789 | 705 | 1084 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Age, y, mean (SE) | 24 (0.07) | 25 (0.05) | 24 (0.09) | 26 (0.06) | 23 (0.18) | 25 (0.12) | 24 (0.19) | 26 (0.13) |

| Male, % (no.) | 50 (2676) | 55 (3428) | 54 (1323) | 55 (2105) | 53 (377) | 50 (891) | 53 (340) | 48 (551) |

| Education, y, mean (SE) | 12 (0.03) | 10 (0.06) | 11 (0.08) | 10 (0.08) | 14 (0.10) | 14 (0.10) | 14 (0.11) | 15 (0.14) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % (no.) | ||||||||

| Mexican | 70 (4358) | 68 (4756) | 66 (1877) | 70 (2879) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Central/South American | 7 (384) | 22 (1495) | 21 (595) | 23 (900) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Puerto Rican | 12 (805) | 5 (380) | 7 (231) | 3 (149) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Other/multiplea | 11 (748) | 5 (419) | 7 (215) | 4 (204) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Asian ethnicity, % (no.) | ||||||||

| Asian Indian | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13 (106) | 30 (552) | 15 (104) | 42 (448) |

| Chinese | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 19 (148) | 17 (325) | 15 (125) | 18 (200) |

| Filipino | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 29 (210) | 15 (235) | 18 (124) | 13 (111) |

| Other/multipleb | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 39 (275) | 39 (677) | 52 (352) | 27 (325) |

| Health behaviors, % (no.) | ||||||||

| Smoking | 20 (1324) | 12 (893) | 11 (341) | 13 (552) | 18 (138) | 13 (261) | 15 (112) | 12 (149) |

| Leisure-time physical inactivity | 36 (2415) | 53 (3870) | 47 (1437) | 58 (2433) | 22 (152) | 34 (578) | 30 (189) | 37 (389) |

Note. N/A = not applicable. Characteristics are weighted using weights provided by the National Health Interview Survey. Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding error.

Includes Cuban, Dominican, multiple Hispanic, other Latin American, and other Spanish subgroups.

Includes Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, and other/multiple Asian subgroups.

Variables

We defined smoking as current versus never or former smoking and LTPI as no activity versus any moderate or vigorous activity per week. Independent variables included education, nativity, nativity and age at immigration, Hispanic or Asian subgroup, gender, and current age. We defined education as years of completed schooling. The variable for nativity indicated whether the individual was born in the United States versus other countries or US territories. To test the hypothesis concerning both nativity and age at immigration, we recoded the variable for nativity into 3 categories: US-born, immigration at or before age 15 years, and immigration after age 15 years. We selected age 15 years as the cut point to ensure that individuals classified in the younger immigration category would have a few years of exposure to the US environment before adulthood. Immigrants were classified into 1 of the 2 age-at-immigration groups based on age at interview minus years of US residence. The NHIS provides data on years of US residence in intervals (< 1 year, 1 to < 5 years, 5 to < 10 years, 10 to < 15 years, and ≥ 15 years). We approximated years of residence by calculating the mean for each interval and rounding up.

Because data on exact years of residence were unavailable, there was some potential for misclassification. For example, a participant aged 22 years who had been in the United States for 5 to less than 10 years could have immigrated at any age from approximately 13 years to 17 years. Because all individuals in this interval were assigned to 8 years of residence, all participants aged 22 years in this interval were coded as immigrating at age 14 years. Thus, those who actually immigrated at ages 16 or 17 years would have been misclassified in the younger age-at-immigration group (at or before age 15 years). However, participants aged 22 years in all other intervals were correctly classified (i.e., those resident for < 1 year or for 1 to < 5 years were correctly classified as immigrating after age 15 years, and those resident for 10 to < 15 years or > 15 years were correctly classified as immigrating at or before age 15 years). Under the assumption that actual number of years of residence is evenly distributed within each interval, we estimated that the percentage misclassified was 7% of Hispanic immigrants (4% of the full Hispanic sample, including US-born Hispanics) and 4% of Asian immigrants (3% of the full Asian sample). We conducted a sensitivity analysis removing all potentially misclassified individuals from each sample.

Analysis

We estimated a series of logistic regression models for each outcome separately for Hispanics and Asians. We tested the first hypothesis by interacting education and nativity (model 1). In model 2, we included an interaction term for education and the 3-category variable for nativity/age-at-immigration variable. Finally, we determined whether patterns varied by subgroup or gender by including a 3-way interaction term (e.g., education × nativity/age at immigration × subgroup; model 3). Although interactions by subgroup or gender were not significant (see Results), we stratified preliminary analyses by these variables. Because the results did not add substantively to our findings, we elected not to stratify analyses by either variable.

We assessed the statistical significance of sets of interaction terms using adjusted Wald tests and tested for differences in education gradients between the 2 age-at-immigration categories (model 2) using a postestimation test. All analyses were conducted in Stata 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), using survey estimation commands to account for the complex sampling design of the NHIS.25

RESULTS

We present weighted characteristics of Hispanic and Asian young adults by nativity and age at immigration in Table 1. Hispanics had less education on average than did Asians in each category. Mexicans were the largest Hispanic subgroup in all categories, but among Asians no single group predominated.

For both Hispanics and Asians, smoking prevalence was higher among US-born individuals than among foreign-born individuals, whereas the reverse was true for LTPI prevalence. Among Asian immigrants, those who had arrived in the United States at or before age 15 years were more likely to smoke than were those who had immigrated after age 15 years. The opposite pattern was evident for Hispanics, although the difference between age-at-immigration groups was not significant. For both Hispanics and Asians, LTPI was more common among individuals with older age at immigration than for those with younger age at immigration. All differences were statistically significant (P < .05), with the noted exception.

Results from logistic regressions of smoking and LTPI for Hispanics and Asians are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Our first hypothesis posited that education gradients in both outcomes are weaker for foreign-born populations than for US-born populations. This hypothesis was confirmed for Hispanics, based on the significance of the odds ratios for the education × nativity interaction terms for both smoking and LTPI (model 1). The odds ratios for education × nativity were greater than 1.00 (and statistically significant), which indicates that for each additional year of education, foreign-born Hispanics had less decrease in the odds of smoking and LTPI than did US-born Hispanics (the reference group). Education associations did not vary by nativity for Asians for either behavior (Table 3). No significant differences occurred in these patterns by subgroup or gender for Hispanics or Asians (i.e., 3-way interactions for education × nativity × subgroup or gender were not significant; data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Results of Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Smoking and Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity Among Hispanics Aged 18–30 Years (n = 13 345): National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2000–2008

| Smoking |

Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity |

|||

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.02, 1.05) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Male | 2.49 (2.19, 2.84) | 2.49 (2.19, 2.84) | 0.67 (0.61, 0.73) | 0.67 (0.61, 0.73) |

| Education | 0.87 (0.83, 0.90) | 0.87 (0.83, 0.91) | 0.80 (0.77, 0.83) | 0.80 (0.77, 0.84) |

| Nativity (Ref: US-born) | 0.12 (0.07, 0.22) | 0.51 (0.30, 0.87) | ||

| Nativity/age at immigration (Ref: US-born) | ||||

| Immigrated ≤ age 15 y | 0.19 (0.09, 0.37) | 0.63 (0.34, 1.18) | ||

| Immigrated > age 15 y | 0.10 (0.05, 0.19) | 0.46 (0.27, 0.79) | ||

| Hispanic subgroup (Ref: Mexican) | ||||

| Central/South American | 1.13 (0.93, 1.39) | 1.12 (0.92, 1.37) | 0.84 (0.73, 0.97) | 0.83 (0.72, 0.96) |

| Puerto Rican | 1.95 (1.59, 2.40) | 1.97 (1.60, 2.43) | 1.05 (0.90, 1.23) | 1.07 (0.91, 1.25) |

| Other/multiple Hispanic | 1.89 (1.54, 2.31) | 1.89 (1.54, 2.31) | 1.33 (1.13, 1.57) | 1.34 (1.14, 1.58) |

| Nativity × education (Ref: US-born × education) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) | ||

| Nativity/age at immigration × education (Ref: US-born × education) | ||||

| Immigrated ≤ age 15 y × education | 1.08 (1.02, 1.14) | 1.07 (1.01, 1.12) | ||

| Immigrated > age 15 y × education | 1.16 (1.10, 1.23) | 1.13 (1.08, 1.18) | ||

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

TABLE 3.

Results of Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Smoking and Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity Among Asians Aged 18–30 Years (n = 2528): National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2000–2008

| Smoking |

Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity |

|||

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 1.01 (1.01, 1.08) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) |

| Male | 2.48 (1.94, 3.18) | 2.54 (1.97, 3.26) | 0.66 (0.52, 0.84) | 0.67 (0.52, 0.85) |

| Education | 0.87 (0.76, 0.98) | 0.86 (0.76, 0.98) | 0.88 (0.80, 0.97) | 0.89 (0.81, 0.99) |

| Nativity (Ref: US-born) | 0.31 (0.05, 2.11) | 3.21 (0.75, 13.77) | ||

| Nativity/age at immigration (Ref: US-born) | ||||

| Immigrated ≤ age 15 y | 1.79 (0.20, 16.24) | 6.51 (1.19, 35.56) | ||

| Immigrated > age 15 y | 0.10 (0.01, 0.83) | 4.41 (0.88, 22.04) | ||

| Asian subgroup (Ref: Asian Indian) | ||||

| Chinese | 0.97 (0.60, 1.58) | 1.06 (0.65, 1.72) | 0.92 (0.65, 1.29) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.44) |

| Filipino | 2.59 (1.65, 4.04) | 2.82 (1.78, 4.45) | 0.89 (0.63, 1.25) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.44) |

| Other/multiple Asian | 2.42 (1.63, 3.58) | 2.69 (1.79, 4.05) | 0.90 (0.66, 1.20) | 1.03 (0.75, 1.41) |

| Nativity × education (Ref: US-born × education) | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | ||

| Nativity/age at immigration × education (Ref: US-born × education) | ||||

| Immigrated ≤ age 15 y × education | 0.93 (0.80, 1.09) | 0.90 (0.79, 1.01) | ||

| Immigrated > age 15 y × education | 1.16 (1.01, 1.33) | 0.96 (0.86, 1.07) | ||

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Our second hypothesis predicted differences in education gradients for the 2 outcomes by both nativity and age at immigration. We evaluated this hypothesis by testing the 2 individual interaction terms shown in model 2 as a set, via adjusted Wald tests, then evaluating the statistical significance of individual interaction terms. The results of the adjusted Wald tests supported this hypothesis for smoking for both populations (Hispanics: F = 13.03, P < .001; Asians: F = 8.14, P < .001) and for LTPI for Hispanics (F = 15.41, P < .001). For Hispanics, the statistical significance of the individual interaction term in model 2 for the younger age-at-immigration group (education × immigrated at or before age 15 years) indicates that for each additional year of education, this group exhibited less decrease in the odds of either behavior than did the US-born group (the reference group). The same was true for those who had immigrated after age 15 years (education × immigrated after age 15 years) relative to the US-born group.

A postestimation test (data not shown) suggested that there was also a significant difference in the interaction terms for the 2 age-at-immigration groups (P < .01 for either outcome). Among Asians, significant differences were evident for smoking only for the group that had immigrated after age 15 years relative to the US-born group (model 2). The difference between the terms for the 2 age-at-immigration groups was also statistically significant (P < .001; data not shown). We found no significant differences in these patterns by subgroup or gender for Hispanics or Asians (data not shown).

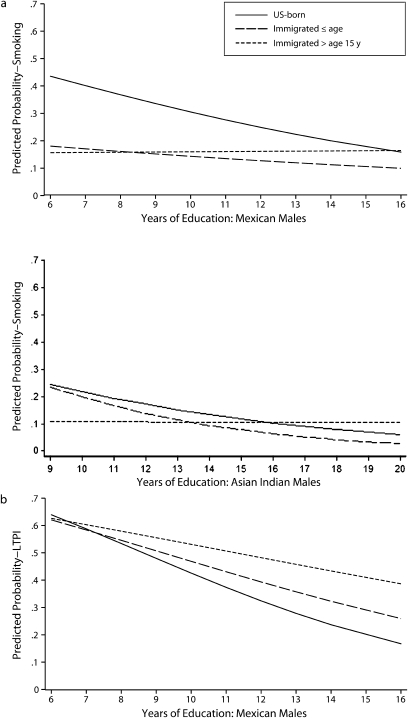

To illustrate these relationships, significant interactions from model 2 are graphed in Figure 1. The graphs are based on predicted probabilities; because these probabilities require specifying a value for each variable in the model, they are depicted for specific subgroups. The particular group selected is not important; given that the 3-way interactions were not significant, the slopes of the lines in the figure would be the same for any subgroup (or either gender). We graphed associations for Mexicans and Asian Indians because they were among the largest subgroups in each population. Patterns are depicted for males aged 25 years from each group. We graphed associations from 6 to 16 years of education for Mexicans and for 9 to 20 years of education for Asian Indians, to avoid emphasizing patterns at education levels uncommon to each population.

FIGURE 1.

Predicted probabilities of (a) smoking and (b) LTPI by education and nativity/age at immigration: National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2000–2008.

Note. LTPI = leisure-time physical inactivity. Although Mexican males and Asian Indian males are depicted, patterns do not vary by subgroup in the Hispanic or Asian populations or by gender. These particular subgroups were selected for illustrative purposes only.

In the Mexican male population, the steepest education–smoking gradient was evident among the US-born group. In the Mexican population that immigrated at a younger age, a shallower—but still inverse—gradient was evident (Figure 1, a). The Asian Indian population that immigrated at a younger age exhibited an inverse gradient very similar to that of the US-born population (Figure 1, a). Populations that immigrated after age 15 years in both groups showed a slightly positive gradient. For LTPI among Mexicans, the steepest inverse gradient was seen in the US-born population, and the shallowest was seen in the population immigrating after age 15 years, with the population immigrating at or before age 15 years falling in between (Figure 1, b).

The figure suggests that patterns for smoking are distinct from patterns for LTPI. The probability of smoking was similar among more educated individuals of Mexican origin, regardless of nativity or age at immigration. However, among the US-born population, this probability was sharply higher among the less educated, relative to both age-at-immigration groups. (A similar, although less pronounced, pattern was apparent for Asian Indians with less education who are either US-born or who immigrated ≤ age 15 years, relative to those who immigrated > age 15 years.) For LTPI, in contrast, greater differences between the 3 Mexican-origin groups were seen among the more (vs less) educated.

To examine potential bias associated with misclassification of immigrants into the 2 age-at-immigration groups, we excluded all individuals who could have been misclassified from analysis. Results (not shown) were identical to those for the full sample, with the exception that there was no significant difference in education–smoking associations for US-born Hispanics versus those who immigrated at or before age 15 years (P = .2).

DISCUSSION

Education differentials were smaller for smoking and LTPI for foreign-born Hispanic young adults than they were for those born in the United States, but for Asians the differentials were similar for both behaviors regardless of nativity. Among Hispanic populations, education gradients for both smoking and LTPI were affected not only by nativity but also by age at immigration among the foreign-born. The gradient of the young adult population that immigrated during childhood or adolescence more closely resembled that of the US-born population than did the gradient of the population that resided in their home countries during these periods. Although we found no overall influence of nativity on the education gradient for either behavior in the Asian young adult population, the population that immigrated at older ages showed a weak positive education gradient for smoking, and that of the population that immigrated in childhood or adolescence was statistically similar to the inverse gradient of the US-born population. These findings support the hypothesis that developmental contexts in the United States and native countries differentially shape the relationship between education and some health behaviors in young adulthood.

Our results provide guidance for future research aimed at identifying the mechanisms that lie beneath observed patterns and for public health efforts that target the groups most at risk for smoking and LTPI. Somewhat different mechanisms may underlie variation in education gradients for smoking and for LTPI. The likelihood of smoking is higher among the least educated US-born Hispanics; the same pattern, although less pronounced, is evident among US-born Asians and Asians who immigrated at or before age 15 years. There is less difference in the likelihood of smoking among the most educated individuals, regardless of nativity or age at immigration. Thus, mechanisms operating at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum may be particularly important to understanding the degree to which exposure to different early-life environments generates smoking disparities in young adulthood. These mechanisms may include differences between the United States and sending countries with regard to social determinants of smoking among youths in lower socioeconomic strata, such as acceptability of smoking behaviors, stress, or discrimination.6 Economic factors, such as differences in the affordability of cigarettes among lower-SES adolescents in the United States versus sending countries, may also be important. Our findings further suggest that smoking interventions be targeted toward less educated Hispanics and Asians with early-life exposure to the US environment, particularly the US-born individuals in both groups, as well as foreign-born Asians.

For LTPI among Hispanics, differences in education gradients by nativity and age at immigration appear to be driven by more educated rather than less educated populations. Thus, mechanisms operating at the higher end of the socioeconomic spectrum in childhood and adolescence may be particularly important to understanding observed patterns. For example, norms sanctioning inactivity in higher socioeconomic strata, which may be absorbed fairly early in life, may be more developed in the United States than in parts of Latin America and the Caribbean. Unlike smoking, findings suggest that efforts to decrease disparities in LTPI among Hispanics need not target particular nativity or age-at-immigration groups, but rather all young adults with lower education levels.

Our findings are consistent with hypotheses surrounding developmental contexts, but we were unable to rule out alternative explanations. Health selection associated with immigration to the United States may be more pronounced among lower-SES immigrants4; however, prior research found little evidence of health selection relative to education–smoking gradients in the Mexican immigrant population.7 Although to our knowledge no similar study concerning exercise exists, the patterns observed here for LTPI among Hispanics are inconsistent with socioeconomically determined health selection. Differences in education–LTPI associations by nativity and age at immigration are largely apparent among more educated Hispanics. There is little reason to expect that, among more educated Hispanics, physically inactive individuals would be more likely to immigrate than would the physically active, given the physical demands of transit to and settlement in the United States.

A second alternative explanation for differences in education–LTPI gradients among Hispanics concerns labor-market issues. More-educated Hispanic immigrants may have to work longer hours than do US-born Hispanics because of poorer labor-market access, leaving less time for discretionary physical activity.26 However, a sensitivity analysis (not shown) among working young adults found comparable results for LTPI, controlling for the number of hours worked in the last week, with the exception that education associations were similar for those who had immigrated at young ages versus the US-born population.

Although previous research has found differences in education gradients in physical activity by nativity among Asians,5 we found no variation in the relationship between education and LTPI among Asians by either nativity or age at immigration. Our study was limited to young adults, so our findings may indicate an age or cohort effect. Given that variation in education–smoking gradients is evident by nativity and age at immigration among Asians, additional investigation may clarify why LTPI does not follow a similar pattern.

The data available to us only supported examination of leisure-time inactivity, rather than nonleisure-time inactivity.27 LTPI may have less health relevance for less-educated young adults, given that they are more likely to find employment in occupations requiring physical exertion than are more-educated adults. In a supplemental analysis (results not shown), we found that the association between LTPI and obesity was similar for Hispanic young adults in manual versus nonmanual occupations (P for interaction = 0.13). Additionally, obesity prevalence was equally high (approximately 20%) among Hispanic young adults regardless of occupation, indicating that working in manual occupations alone is insufficient for obesity prevention. Our findings suggest that leisure-time physical activity may represent a health resource for Hispanic young adults regardless of SES.

Education quality and economic returns to education may differ for those educated in the United States as opposed to those educated in their native countries, a factor which may have affected our results.28–31 If poorer-quality education in sending countries influenced the observed patterns, rather than the social mechanisms discussed above, we would expect a greater probability of smoking and LTPI in young adults in the 2 age-at-immigration groups across the educational spectrum, but this was not the case. Lower economic returns for education in the United States for Hispanic and Asian young adult immigrants might explain why those with less education were less likely to smoke, given that these individuals may have had a smaller amount of disposable income with which to purchase cigarettes.32 However, this explanation seems unlikely, given that similar patterns were not observed for LTPI, which is also likely to depend to some extent on financial resources.33,34

This analysis was subject to limitations in addition to those already noted. Lack of available data precluded investigation of family, peer, and neighborhood mechanisms that may underlie observed patterns. An understanding of these mechanisms would provide additional information to be used in targeting interventions. Smoking status in particular may be differentially reported by education, nativity, or age at immigration among Hispanics and Asians, which may have influenced our results.35–38 Also, the threshold of age 15 years for immigration during formative periods was chosen somewhat arbitrarily. However, findings (not shown) were substantively similar when age at immigration was dichotomized at age 12 years, pointing to the importance of exposure to the US context in general during formative phases.

Despite these limitations, this study makes important contributions to our understanding of social gradients in health behaviors. Our results suggest that not only nativity but also early life contexts may be crucial to understanding how gradients in health behaviors are differentially shaped in diverse populations. Although previous research has made substantial progress in identifying mechanisms operating between socioeconomic disadvantage and health behaviors, this analysis suggests that there is a need to consider unique early-life pathways for immigrant populations, relative to US-born populations, based on age at immigration. Such research may further inform efforts to reduce health disparities in Hispanic and Asian populations and may hold broader lessons concerning the origins of social gradients in health and health behaviors in high-income countries.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

We thank Anne Pebley and Eli Puterman for advice on and assistance with the study.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study because all data were obtained from publicly available secondary sources.

References

- 1.Goldman N. Social inequalities in health: disentangling the underlying mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;954(1):118–139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49(1):15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Sánchez BN, Acevedo-Garcia D. Differential effect of birthplace and length of residence on body mass index (BMI) by education, gender and race/ethnicity. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(8):1300–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman N, Kimbro RT, Turra CM, Pebley AR. Socioeconomic gradients in health for White and Mexican-origin populations. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2186–2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimbro RT, Bzostek S, Goldman N, Rodriguez G. Race, ethnicity, and the education gradient in health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leu J, Yen IH, Gansky SA, Walton E, Adler NE, Takeuchi DT. The association between subjective social status and mental health among Asian immigrants: investigating the influence of age at immigration. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1152–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buttenheim A, Goldman N, Pebley A, Wong R, Chung C. Do Mexican immigrants “import” social gradients in health behaviors to the US? Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1268–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams SS, Mulhall PF. Where public school students in Illinois get cigarettes and alcohol: characteristics of minors who use different sources. Prev Sci. 2005;6(1):47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:41–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilman SE, Abrams DB, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):802–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon-Larsen P, McMurray RG, Popkin BM. Determinants of adolescent physical activity and inactivity patterns. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vázquez-Segovia LA, Sesma-Vázquez S, Hernandez-Avila M. El consumo de tabaco en los hogares en México: resultados de la Encuesta de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares, 1984–2000 [Smoking in Mexican households: findings from the Encuesta de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares, 1984–2000]. Salud Publica Mex. 2002;44(suppl 1):S76–S81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caballero R, Madrigal L, Hidalgo S. El consumo de tabaco, alcohol y otras drogas ilegale en los adolecentes de diferentes estratos socioeconomicos de Guadalajara [Smoking, drinking and use of illicit drugs among adolescents from different social groups in Guadalajara]. Salud Ment. 1999;22:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Florez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1243–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unger JB, Cruz TB, Rohrbach LA, et al. English language use as a risk factor for smoking initiation among Hispanic and Asian American adolescents: evidence for mediation by tobacco-related beliefs and social norms. Health Psychol. 2000;19(5):403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unger JB, Reynolds K, Shakib S, Spruijt-Metz D, Sun P, Johnson CA. Acculturation, physical activity, and fast-food consumption among Asian-American and Hispanic adolescents. J Community Health. 2004;29(6):467–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallis JF, Prochaska J, Taylor W. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(5):963–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Horst K, Paw M, Twisk J, Van Mechelen W. A brief review on correlates of physical activity and sedentariness in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1241–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowda M, Ainsworth BE, Addy CL, Saunders R, Riner W. Correlates of physical activity among US young adults, 18 to 30 years of age, from NHANES III. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Passel J. The Size and Characteristics of the Unauthorized Migrant Population in the US: Estimates Based on the March 2005 Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capps R. A Profile of the Low-Wage Immigrant Workforce. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botman S, Moore T, Moriarity C, Parsons V. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1995–2004. Vital Health Stat 2 2000;130:1–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 11.0. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren R. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: 1990 to 2000. Washington, DC: Office of Policy and Planning, US Immigration and Naturalization Service; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kandula NR, Lauderdale DS. Leisure time, non-leisure time, and occupational physical activity in Asian Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(4):257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrer A, Riddell WC. Education, credentials, and immigrant earnings. Can J Econ. 2008;41(1):186–216 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bratsberg B, Ragan JF. The impact of host-country schooling on earnings: a study of male immigrants in the United States. J Hum Resources. 2002;37(1):63–105 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catanzarite L. Brown-collar jobs: occupational segregation and earnings of recent-immigrant Latinos. Sociol Perspect. 2000;43(1):45–75 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J, Barro R. Schooling quality in a cross-section of countries. Economica. 2001;68(272):465–488 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roeseler A, Burns D. The quarter that changed the world. Tob Control. 2010;19(suppl 1):i3–i15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(2):60–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diez Roux AV, Evenson KR, McGinn AP, et al. Availability of recreational resources and physical activity in adults. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(3):493–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wewers ME, Dhatt RK, Moeschberger ML, Guthrie RM, Kuun P, Chen MS. Misclassification of smoking status among Southeast Asian adult immigrants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(6, pt 1):1917–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher MA, Taylor GW, Shelton BJ, Debanne S. Age and race/ethnicity–gender predictors of denying smoking, United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(1):75–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher MA, Taylor G, Shelton B, Debanne S. Sociodemographic characteristics and diabetes predict invalid self-reported non-smoking in a population-based study of US adults. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wills TA, Cleary SD. The validity of self-reports of smoking: analyses by race/ethnicity in a school sample of urban adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(1):56–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]