Abstract

We propose a new approach to guide health promotion practice. Health promotion should draw on 2 related systems of reasoning: an evidential system and an ethical system. Further, there are concepts, values, and procedures inherent in both health promotion evidence and ethics, and these should be made explicit. We illustrate our approach with the exemplar of intervention in weight, and use a specific mass-media campaign to show the real-world dangers of intervening with insufficient attention to ethics and evidence. Both researchers and health promotion practitioners should work to build the capacities required for evidential and ethical deliberation in the health promotion profession.

We propose a framework to formalize 2 central aspects of health promotion practice—ethics and evidence—and to guide future practice. This framework is speculative, based on our professional and academic knowledge and the literature. It entails 2 iteratively related systems of reasoning: an evidence-based system and an ethics-based system. Evidence-informed practice and ethical reasoning both aim to maximize human well-being by applying explicit evaluative frameworks.1 Evidence and ethics are implicitly related: evidence-based practice may be more ethical, and ethically sensitive practice more effective. Health promotion practice would benefit by deliberately bringing evidence and ethics together; to specify the concepts, values, and procedures inherent in each; and to achieve this integration through a detailed study of current practices in health promotion.

The definition of health promotion is contested and values driven,2,3 but researchers and practitioners widely acknowledge that health promotion occurs at different levels—from standardized top-down national programs to unique grass-roots initiatives. We illustrate our arguments using a national social marketing campaign,4 but we do not intend to imply that local programs are less worthy of examination.

The need to integrate evidence and ethics in health promotion becomes especially critical when large-scale intervention for a problem is urged, but guidance for action is limited. Body weight is a good example of this discrepancy. In recent years, “overweight and obesity” has been increasingly talked about and accepted as a global problem and threat to public health.5–10 This discourse has attracted political attention, with concomitant expansion in intervention. However, limited evidence or formal ethical debate is available to guide such action. Because body weight exemplifies the problems facing health promotion professionals in relation to evidence and ethics, we use intervention for this issue to illustrate our arguments. The Australian social marketing campaign we examine closely (How Do You Measure Up?) is focused on weight. Next, we consider the evidence and ethics of health promotion, before examining the benefits of a more integrated approach that makes values explicit.

FINDING AN EVIDENCE BASE FOR HEALTH PROMOTION

The search for an evidence base for health promotion reflects the widespread influence of evidence-based medicine.11 The evidence-based medicine movement advocates applying epidemiological, population-level evidence to decisions about clinical care.12–14 Subsequent iterations of evidence-based practice have expanded to other aspects of health-related activity, including multilevel and complex programs targeting whole communities.15,16 Researchers agree that health promotion needs evidence to set priorities, guide advocacy, and demonstrate value.17–20 However, evidence-informed practice is never straightforward21 and is considered especially problematic for health promotion, not least because it is social and political, involving contests between community, corporate, bureaucratic, and political stakeholders.20,22,23

One practical problem for evidence-informed health promotion is an absence of evidence. There is often evidence that something should be done (e.g., needs assessment, measures of prevalence and preventability of risks and conditions), but there is rarely evidence regarding what should be done (e.g., the effectiveness of health promotion intervention) or how to do it (e.g., evaluation of the health promotion process).16 More broadly, debates about evidence-informed health promotion hinge on the nature of evidence for health promotion, in particular the transferability of clinical epidemiology methods and “rules of evidence” to health promotion research.22

Concerns have focused on “levels of evidence” hierarchies, which have randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses at their pinnacle.24 Authors argue that simplistically applying such hierarchies can devalue investigation into both the human subjectivity and the social and cultural complexity that are so important for health promotion.25–31 Researchers also argue that evidence hierarchies may skew the evidence base and thus evidence-informed health promotion practice. They focus on questions that can be answered via randomized controlled trials; via a self-fulfilling cycle, this leads to “evidence-based” programs that target only the individual behaviors that can be studied in such trials.26 Expanded approaches to evaluating health promotion evidence have been proposed, but the challenges are not fully resolved and debates are ongoing.20,23,28,32–35

Body weight exemplifies the general problems regarding evidence in health promotion. Many would argue that weight is a justified target for intervention, but even this argument is contested: some propose that fitness is more important than weight.36–38 As “overweight and obesity” is a relatively recent health promotion target, intervention evidence is limited.39 Particularly, there is little evidence for whole-of-population intervention targeting the weight of adults.40 Multifaceted interventions that address social, economic, and community factors based on the New Public Health have been insufficiently researched,41 for reasons that include feasibility, cost, and political acceptability.34 Large-scale innovative social interventions, or those with controversial political and commercial implications such as the regulation of food manufacturing, marketing, and distribution, are rarely evaluated in ways that would satisfy “hierarchy of evidence” criteria. Such evidence has, however, been generated for interventions targeting behavioral risk factors (such as fruit and vegetable consumption or time spent watching television) and for education interventions in primary schools.42 Because interventions with the “greatest potential for population health impact” have the least “certainty of effectiveness,”43(p407) it has been proposed that more flexible approaches should be developed that consider the uncertainty, risks, and potential benefits of promising obesity prevention programs.43–45 As yet, these do not exist.

FINDING AN ETHICS BASE FOR HEALTH PROMOTION

Ethics is the study of what should be done: a prescriptive, systematic analysis of what is required for human well-being.1 Whereas bioethics has had a significant impact on clinical medicine and medical technology since the 1960s, commentators argue that public health, and health promotion in particular, have been left behind.1,46–49 The development of public health ethics is only just gaining momentum50: the first US Ethics and Public Health Model Curriculum was released in 2003,51 the first peer-reviewed journal in the field was launched in 2008,52 and there is only 1 formal code of ethics for public health internationally.53 The International Union for Health Promotion and Education, which represents health promotion professionals internationally, is now considering a code of ethics for health promotion. This development suggests that explicating the ethics of practice is now recognized as an important issue by health promotion professionals.54 The endeavor is not without its problems, however, the most fundamental being uncertainty regarding the purpose of health promotion.2,47,55,56

Finding an Ethics Base for Health Promotion Regarding Body Weight

As with evidence, ethics poses problems for population intervention aimed at body weight. Body weight is an ethically charged issue for many reasons. Our identities are tightly bound up with our bodies, so messages about our bodies may seem indivisible from messages about our intrinsic worth. This problem worsens when “overweight and obesity” is constructed as a single “at risk” category, in which a body weight index (BMI; defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 26 or 36 may be discussed in similar terms. Food is a symbolically and socially central aspect of human life, such that attempting to change people's food habits can be an intervention into their culture, society, and relationships. Physical activity also has different meanings for different cultural and socioeconomic groups, with implications for exercise interventions.1,57–59

Specifying Ethically Relevant Concepts

A central problem in the ethics of health promotion is conceptual vagueness. Health promotion charters promote ethically relevant concepts such as justice, health equity, enablement, and empowerment, and health promotion professionals are undoubtedly deeply committed to these concepts and strive to turn them into sound practices. Nonetheless, many authors have noted that these charters are abstract and fail to define concepts such as justice in any detail.48,60–62 For this reason, making progress in this area will require specification of ethically relevant concepts, including the dimensions along which they may vary,63 based on detailed engagement with theory and with health promotion practices. We illustrate how this might work by specifying 2 concepts, coercion and stigmatization, using a social marketing campaign case study.

Coercion.

Coercion can be loosely defined as a form of forcible constraint.48,50 Coercion as such does not appear in health promotion charters; however, defining unreasonable coercion is a central concern in public health ethics. This literature is relevant to thinking about the ethics of health promotion because achievement of population health targets is likely to require coercion of some kind, encroaching on individuals’ liberty and autonomy. The regulations often framed as enabling structural interventions (e.g., smoke-free legislation, firearm bans, or alcohol taxes) are in effect coercive.48,50 These restrictions may be popular and produce health benefits, but they also coerce targeted individuals.

Let us consider coercion in relation to social marketing campaigns. Social marketing represents a fraction of health promotion activity, but its resource intensiveness and reach make it ripe for scrutiny. Social marketing is often framed as a noncoercive, informational intervention; this framing is not always accurate. The purpose of social marketing campaigns may range from educating consumers so they can make informed choices to persuading them to conform.1,64–67 Further, coercion itself might range from “reasonable” to “unreasonable.” The ethics literature suggests that unreasonable coercion might include teaching people to perceive themselves negatively in new ways or exposing them to fear about new and previously unidentified risks, especially if they are at low risk of actual disease, suffer no apparent symptoms, and may never experience the predicted impact on health outcomes.1,64–67

How might these ethically relevant concepts play out in a real example of a social marketing campaign targeting weight? How Do You Measure Up? is a campaign widely distributed through multiple mass-media channels in Australia; materials are available at the campaign Web site.4 A 60-second television commercial features a male protagonist; there is no set except a giant tape measure running along the floor directly toward the viewer. The protagonist walks along the tape measure toward the camera wearing only modest white underpants. At the outset of the television commercial, he is “20-something”; later in the commercial he is “aged” and made fatter to match his position on the tape measure. The script specifies that he begins with a waist measurement of 84 centimeters (33 in) and ends with a measurement of 102 centimeters (40 in). As he walks toward the viewer he says, “You know how it is—you settle down, put on a few kilos. But I'm not worried. Then you have kids, life gets busier, you let yourself go a bit. I'm not worried. But when I first realized it was affecting my health—well, yeah, I got worried.” This script is interspersed with an unseen narrator providing technical information, including “Unhealthy eating and drinking and not enough physical activity can seriously affect your health,” “For most people, waistlines of over 94 cm for men and 80 cm for women increase the risk of some cancers, heart disease and type 2 diabetes,” and “The more you gain, the more you have to lose.”4 The climax of the commercial revolves around the protagonist's daughter, as he first realizes overweight is affecting his health when he can't catch his daughter in a game of tag. In the following scene, his daughter runs into view beaming, but, presumably foreseeing the early death of her overweight father, rapidly assumes a serious and concerned expression; he becomes similarly stricken. This segment is followed by the campaign slogans: “The more you gain, the more you have to lose” and “How do you measure up?”

This campaign satisfies several criteria for unreasonable coercion.1,64–67 It plays on parental guilt in an attempt to effect behavior change and is designed to teach all viewers with a BMI of more than 25 to perceive themselves negatively in new ways and to imagine their girth leading to cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. It emphasizes that small increments in waist measurement increase risk and so may create self-surveillance in low-risk individuals at stable weight and low risk of current or future disease. These problems are in part a result of applying population-level risk data to create messages targeting individuals, and of focusing on the single risk factor of body weight.

Stigmatization.

Stigmatization is a form of potential iatrogenesis in health promotion, and as such is another key concept for health promotion ethics.48,49,66,68–70 The sociological literature about stigma can help us specify this concept. Stigma is about social unacceptability: a form of “spoiled identity.”71 Stigma links individuals to negative stereotypes, and stigmatization can result in prejudice and discrimination. People interact differently with those who are stigmatized, which can further undermine a stigmatized person's sense of self. Unless a stigmatized person can resist the “spoiled identity” imputed to them—a difficult task at the heart of many activist movements—the negative effects of stigma can be avoided only by “passing as normal” or changing the people with whom one interacts.71,72

These insights suggest dimensions of the ethically charged concept of stigma. Human characteristics are likely to vary from nonstigmatizing to highly stigmatizing. Stigmatizing characteristics are likely to be more persistently visible—thus preventing “passing as normal”— and to generate reactions that suggest the characteristic is not “normal” (e.g., eliciting staring, pointing, talking, or embarrassed looks). A person might be considered more or less responsible for the characteristic; for example, a person with a congenital condition may be stigmatized but treated kindly, whereas a person with a facial scar from a street fight may be stigmatized and feared. An intervention could increase stigmatization of a characteristic by drawing attention to it and encouraging people to react differently to it. Attributions of responsibility may color this process.

This factor is particularly relevant to media campaigns on weight. There is evidence of higher-weight people being stigmatized72 in settings such as school playgrounds, sports and gym facilities, fashion stores, and health services.68 This has implications for self esteem, body image, and self harm.36,59 A mass-media campaign such as How Do You Measure Up? may encourage different responses to heavier people, including blaming them for their weight.1,57–59 Further, weight is persistently visible—unlike, for example, physical inactivity, blood pressure, or diabetes—and thus easier to stigmatize. In How Do You Measure Up? this stigmatization may be worsened by a 30-second follow-up television commercial showing the same protagonist confidently stating that “from today” he is going to “turn his life around” with diet and exercise. This statement is intended to stimulate action, but may also encourage blame of those who do not simply decide to “turn their lives around” because of personal, experiential, socioeconomic, physiological, and other circumstances.

Environmental and structural approaches to preventing weight gain, such as alterations to the food supply, may be less stigmatizing than are mass-media interventions like How Do You Measure Up?. Although mass-media campaigns are targeted and evaluated at the population level, they may also have a deeply personal and emotional effect on individuals, with little capacity to reflect the needs of those individuals. A campaign focused on waist circumference cannot recognize a person's unique lifetime struggle with weight loss, be sensitive to a long-held shame felt toward one's body, or recognize that someone with a BMI of more than 25 may be fit and well.37,38 At present, evaluation of such interventions does not generally attend to outcomes such as stigmatization.68

ETHICS, EVIDENCE, AND VALUES

We have suggested a 2-fold problem for health promotion: there is insufficient, incomplete evidence to guide decision-making about population-level intervention, and although iconic ethical commitments have been made in health promotion charters, the concepts entailed have not been well specified. Engaging with the values implicit in both evidential and ethical systems of reasoning may help to resolve these problems. The values we hold signify what is important to us. In recent years, in professional fora and international journals, health promotion professionals have expressed a need for deeper examination of the values that underpin health promotion practice.29,46,47,53–56,62,73–76 Values clarification of the kind being advocated in the profession could enable accountability in relation to both ethics and evidence.

The discipline of ethics contains several competing and well-articulated systems of reasoning; these include deontology, utilitarianism, virtue theory, social contract theory, the capabilities approach, and narrative ethics.1 These systems contain clear differences in values. They might value, for example, reason, dignity, moral obligations, achievement of the best possible outcome for the greatest number of people, virtues, individual freedoms, or shared common goods. These valued concepts are often specified at great length in the ethics literature. They must sometimes be traded off against one another (individual freedom against utilitarian maximized benefit, for example). As yet, these formal systems have not made substantial inroads into public health or health promotion practice. Recently, the first model curriculum for public health ethics was published in the United States.51 It took a casuistic approach, encouraging students to consider practical problems but providing limited opportunity to acquire the detailed conceptual tools available in the discipline of ethics. Deeper study is required to understand any of these approaches fully.1

Values are also inherent in the generation and evaluation of evidence, although this is not always evident in the rhetoric of evidence-based practice.46,53,55,76 The notion of evidence itself is now highly valued: it would be absurd to argue that health promotion should not be informed by evidence.26,77 What is at issue is what counts as evidence—that is, how we specify the concept of evidence. This specification will determine which data have the status of evidence conferred upon them.26 The criteria by which certain data come to be designated as evidence, and others scorned, is fundamentally a question of values.28,29,78,79

To ask a question about something is to value it; there is little point inquiring after something that has no value.79,80 Weed has made a useful distinction between scientific and extrascientific values that influence scientists’ work; these are, respectively, things valued collectively by the scientific community and things valued by individual scientists (e.g., arising from political, religious, social, or cultural commitments).81 Both types of values are seen in the generation of evidence. Scientific values create norms for research practice; extrascientific values may contribute to a researcher's choice of research questions or study variables, as well as the interpretation of results. When a study is complete, judgments about causal inference—despite explicit criteria—are also based on values; this is shown in Weed's comparison of 2 meta-analyses on the same question, conducted only months apart, that reached contradictory conclusions.81

Developing rules of evidence for health promotion involves values; these values can shape health promotion by determining the flow of funding. As noted, “evidence hierarchies” explicitly value evidence from randomized controlled trials over other forms of evidence. Some have suggested that this has driven health promotion toward individualistic interventions for which evidence based on randomized controlled trials can be generated; in response, those who value other modes of practicing health promotion have sought to modify the rules of evidence. This contest demonstrates the extent to which debates about evidence-based health promotion, including the way we specify the concept “evidence,” are driven by values.29

A PROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR THINKING ABOUT HEALTH PROMOTION

In this section, we propose a framework for thinking about health promotion that attends especially to evidence, ethics, and values, and their related concepts and tradeoffs.

The General Framework and a Practical Example

We propose 5 principles for planning and evaluating health promotion. These illuminate the good practices already occurring and draw attention to what is currently neglected. In this framework, we refer to relationships as “iterative”; by this we mean that they exist in repeated cycles with feedback of the result of each cycle into the next cycle, allowing incremental modification. Our proposed 5 principles are as follows:

Recognize that health promotion thinking must be responsive to particular situations83—it cannot be universal.

Formally recognize and implement 2 iterative systems of reasoning, an evidence-based system and an ethical system, each containing explicit values.

Clearly specify the evidential and ethical concepts that are valued or devalued in each situation, and the dimensions along which these vary. Use both existing theory and detailed empirical study of the practice of health promotion in the situation.

Be specific about tradeoffs occurring along the identified dimensions—consider how valued or devalued concepts interact.

Prioritize procedural transparency: be certain that processes used for reasoning, defining, and trading off can be explained clearly.

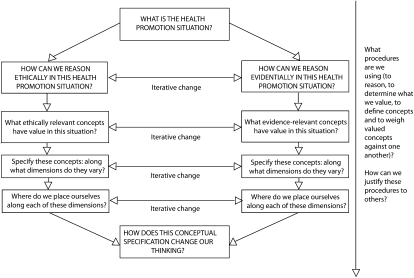

Figure 1 presents a simple schematic of our proposed framework in its most general and flexible form. The framework makes ethics and evidence equally important and highlights their iterative relationship. For example, some evidence would be unethical to generate; other evidence will support ethical reasoning; some “effective” actions may be unethical; and ethical systems could guide action when evidence is lacking. It requires specification of the dimensions along which valued concepts vary, and probably some tradeoffs along these dimensions. Finally, it requires procedural transparency—that is, clear explication of how things were done and why. This prioritization of transparency reveals our own values, arising in part from the enlightenment-influenced, democratic society in which we live. Transparency also has pragmatic benefit, as it allows people to make informed judgments by comparing described values with their own, and the steps undertaken with their own procedural standards.

FIGURE 1.

A general framework for considering health promotion.

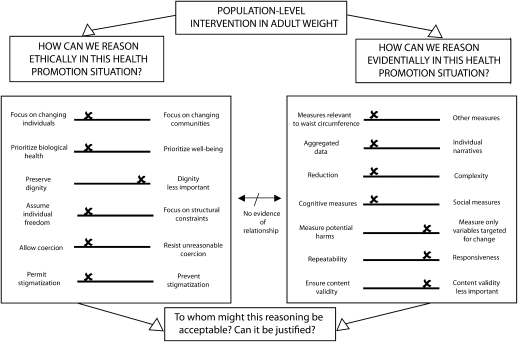

We illustrate the potential usefulness of our general approach by applying it to the specific example of the How Do You Measure Up? campaign and its evaluation report.83 In doing this, we do not mean to suggest that an evaluation report reveals the cognitions of its authors; rather, we suggest that the measures used in an evaluation enact shared values. On the basis of this assumption, we make these observations about what was valued (summarized in Figure 2), noting that there seemed to be little connection between evidence and ethics.

FIGURE 2.

Applying the general framework to the How Do You Measure Up? campaign materials and evaluation report.

Note. There is limited procedural transparency in the evaluation report. This figure reflects the concepts, values, and reasoning implied in the report, highlighting the need for procedural transparency.

The campaign and evaluation implied that the following should be valued in relation to ethics:

Individual change over community or structural change;

Biological health over positive self-image or general well-being (e.g., the report criticized people with BMI > 25 who said their weight was “acceptable”; their general health, fitness, need to enjoy their lives, need to preserve self-esteem, or history of struggle with weight loss were not considered);

Reducing population waist measurements more than avoiding unreasonable coercion (small increases in self-surveillance and self-criticism were reported favorably; e.g., increases in agreement with the statements “My lifestyle is increasing my risk of getting chronic disease” [up from 33% to 39%] and “I'm always trying to make changes to my lifestyle but I find they don't last” [up from 43% to 48%]83); and

Reducing waist measurements more than avoiding stigmatization or preserving the dignity of heavier people.

The campaign and evaluation implied that the following should be valued in relation to evidence:

Reductive, repeatable, cognitive measures and outcomes rather than complex social, narrative, or environmental measures or outcomes;

The concerns of the campaign funders more than the concerns of the campaign targets;

Creation of evidence of targeted change more than monitoring potential harms (there was no measurement of stigmatization or other iatrogenic outcomes); and

Production of evidence more than quality of evidence (e.g., the evaluation reported on awareness of the campaign, ability to recite public health facts, and “intention to act,” data that lack meaning as measures of real change83–85).

Regarding this campaign, the framework creates questions about both evidence and ethics. What type of evidence is there for intervening in waist circumference? What data constitute evidence of effectiveness of such a campaign? What do communities value that might not be reflected in this evidence? What harms and benefits are relevant in this situation, and do the benefits outweigh the harms? The campaign continues to distribute material in which the protagonist and his fictional partner are explicitly critiqued; might this contribute to the stigmatization of heavier people? Why is it necessary for the characters to appear in their underwear? Might the campaign be unreasonably coercive, encouraging unjustifiable fear, self-surveillance, self-loathing, or sense of failure? Such questions encourage a closer relationship between ethical and evidential considerations; for example, how ethically unacceptable outcomes might be monitored and measured and whether, if evaluation suggested ethically problematic outcomes, the campaign might be stopped.

Contribution of Our Proposed Framework to the Existing Literature

There is currently little available literature on the relationship between ethics, evidence, and values in health promotion. Both Hamilton and Bhatti86 and Raphael29 have argued that evidence is underpinned by values and that these values should be made explicit. This supports our argument; we build on their work by suggesting how to make values explicit. Tannahill emphasizes that health promotion can only be informed by (rather than based on) theory and evidence.22 He nominates “ethical principles”—including equity, respect, empowerment, participation, and openness—as prior to either evidence or theory. We believe that it is more useful to consider evidence in an iterative relationship with ethics, and that most of the principles Tannahill lists are in fact ethically relevant concepts that need further specification as outlined in our framework. The Nuffield Council's Stewardship Framework for public health ethics57 is perhaps the most substantial contribution to date. Like our work, this framework engages with concrete cases, acknowledges the centrality of evidence, explicitly frames health as something valued, and seeks to “develop an ethical framework that identifies the most important values to guide public policy in this area.”57(p13) It uses political philosophy to propose a “stewardship model” for governments.52 Detailed consideration of several case studies in the Nuffield report provides an excellent example of the kind of specificity that we have argued for; however, the report does attempt to achieve greater universality than we consider possible. We believe our framework would encourage more deliberate exposition of implicit concepts such as vulnerability, equality, and nonintrusiveness, and perhaps a more formal movement between ethics and evidence in reasoning.

CONCLUSIONS

Transparency in the domains of evidence, ethics, values, and procedures is relevant for all kinds of health promotion. Such transparency may foster greater accountability to the communities we serve, and decades of research suggests that this transparency should increase the effectiveness of risk communication.87 We do not intend to suggest that health promotion professionals are unconcerned with evidence, ethics, and values, but rather to integrate existing work and provide additional “thinking tools.”88 We emphasize that Figures 1 and 2 are summaries, and details of each relevant concept would need to be specified, as we did for stigma and coercion. Some ethically relevant concepts have been extensively specified in the literature, “equity” providing an excellent example.89,90 Prioritization, or trading off, of various ethically relevant concepts has also been addressed to some degree. For example, paternalism,91 social justice, and a relational form of autonomy92 and responsibility93 have all been proposed as preeminent values in this journal alone.

We note that our proposed approach provides questions but cannot supply all of the answers, as these can be worked out only in particular situations. Detailed empirical study of health promotion practice is required to clarify the values and concepts entailed in health promotion; these will vary from situation to situation, and will need to be considered in relation to both evidence and ethics in those situations. The concepts relevant, for example, to an intervention in weight in Australia are likely to differ from those relevant to an intervention in smoking in China, housing in Brazil, or parenting in a disadvantaged community in the United States. Concepts and values are also likely to differ for national versus local levels of intervention. These differences can be identified only through empirical study, and we believe that more health promotion research should be oriented toward this end.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (grant 632679).

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for the development of this article as it did not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Kerridge I, Lowe M, Stewart C. Ethics and Law for the Health Professions. 3rd ed Annandale, Australia: The Federation Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan DR. An Ethic for Health Promotion: Rethinking the Sources of Human Well-Being. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seedhouse D. Health Promotion: Philosophy, Prejudice and Practice. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Better Health Initiative. How Do You Measure Up? [health promotion campaign]. 2009. Available at: http://www.measureup.gov.au/internet/abhi/publishing.nsf/Content/Home. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 5.Stamler J. Epidemic obesity in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(9):1040–1043 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seidell JC. Obesity in Europe: scaling an epidemic. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19(suppl 3):S1–S4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris K. Obesity and NIDDM “epidemic.” Lancet. 1997;350(9073):269 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popkin BM, Doak CM. The obesity epidemic is a worldwide phenomenon. Nutr Rev. 1998;56(4):106–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science. 1998;280(5368):1371–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sackett D, Rosenberg W, Gray J, Haynes R, Richardson W. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what is isn't [editorial]. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feinstein A. Clinical epidemiology, I: the populational experiments of nature and of man in human illness. Ann Intern Med. 1968;69(4):807–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher R, Fletcher S, Wagner E. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sackett D, Haynes R, Guyatt G, Tugwell P. Clinical Epidemiology: A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Little Brown & Co; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rychetnik L, Hawe P, Waters E, Barratt A, Frommer M. A glossary for evidence based public health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(7):538–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brownson R, Fielding J, Maylahn C. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:175–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rychetnik L, Wise M. Advocating evidence-based health promotion: reflections and a way forward. Health Promot Int. 2004;19(2):247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Evidence of Health Promotion Effectiveness: Shaping Public Health in a New Europe. Vanves, France: Commission of the European Union, International Union for Health Promotion and Education; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rychetnik L. Evidence-based practice and health promotion. Health Promot J Austr. 2003;14(2):133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McQueen DV, Jones C, eds. Global Perspectives on Health Promotion Effectiveness. New York, NY: Springer; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little M. “Better than numbers…” A gentle critique of evidence-based medicine. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(4):177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tannahill A. Beyond evidence—to ethics: a decision-making framework for health promotion, public health and health improvement. Health Promot Int. 2008;23(4):380–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Springett J, Owens C, Callaghan J. The challenge of combining “lay” knowledge with “evidence-based” practice in health promotion: Fag Ends Smoking Cessation Service. Crit Public Health. 2007;17(3):243–256 [Google Scholar]

- 24.University of Oxford, Centre for Evidence Based Medicine Levels of evidence. 2009. Available at: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025. Accessed June 3, 2010

- 25.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):887–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerridge I. Ethics and EBM: acknowledging difference, accepting difference and embracing politics. Paper presented at: Critical Debates in Evidence Based Medicine Conference; November 14–16, 2008; University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgerson K. Valuing evidence: bias and the evidence hierarchy of evidence-based medicine. Perspect Biol Med. 2009;52(2):218–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuire WL. Beyond EBM: new directions for evidence-based public health. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48(4):557–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raphael D. The question of evidence in health promotion. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(4):355–367 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kemm J. The limitations of “evidence-based” public health. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):319–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worrall J. What evidence in evidence-based medicine? Philos Sci. 2002;69(3):S316–S330 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(2):119–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang K, Choi BCK, Beaglehole R. Grading of evidence of the effectiveness of health promotion interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(9):832–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans L, Hall M, Jones CM, Neiman A. Did the Ottawa Charter play a role in the push to assess the effectiveness of health promotion? Promot Educ. 2007;(suppl 2):28–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brownson R, Chriqui J, Stamatakis K. Policy, Politics, and Collective Action. Understanding Evidence-based Public Health Policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1576–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gard M, Wright J. The Obesity Epidemic: Science, Morality and Ideology. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sui X, LaMonte M, Laditka J, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity as mortality predictors in older adults. JAMA. 2007;298(21):2507–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blair S, Brodney S. Effects of physical inactivity and obesity on morbidity and mortality: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(11 suppl):S646–S662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obesity Working Group Obesity in Australia: A Need for Urgent Action. Canberra, Australia: National Preventative Health Taskforce; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 40.NSW Centre for Overweight and Obesity A literature review of the evidence for interventions to address overweight and obesity in adults and older Australians. October 2005. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/healthyactive/publishing.nsf/Content/literature.pdf/$File/literature.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2010

- 41.Livingstone MB, McCaffrey TA, Rennie KL, Livingstone MBE. Childhood obesity prevention studies: lessons learned and to be learned. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(8A):1121–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King L, Hector D. Building Solutions for Preventing Childhood Obesity: Overview Module. Sydney, Australia: NSW Centre for Overweight and Obesity; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNeil DA, Flynn MAT. Methods of defining best practice for population health approaches with obesity prevention as an example. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006;65(4):403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gill T, King L, Caterson I. Obesity prevention: necessary and possible. A structured approach for effective planning. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64(2):255–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swinburn B, Gill T, Kumanyika S. Obesity prevention: a proposed framework for translating evidence into action. Obes Rev. 2005;6(1):23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sindall C. Does health promotion need a code of ethics? Health Promot Int. 2002;17(3):201–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker E, Gould T, Fleming M. Ethics in health promotion—reflections in practice. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18(1):69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Neill O. Public health or clinical ethics: thinking beyond borders. Ethics Int Aff. 2002;16(2):35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bayer R. Stigma and the ethics of public health: not can we but should we. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayer R, Fairchild A. The genesis of public health ethics. Bioethics. 2004;18(6):473–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jennings B, Kahn J, Mastroianni A, Parker LS. Ethics and Public Health: Model Curriculum. Washington, DC: Health Resources and Services Administration, Association of Schools of Public Health and Hastings Centre; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nuffield Council on Bioethics Public Health Ethics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Public Health Leadership Society Principles of the ethical practice of public health. 2002. Available at: http://phls.org/CMSuploads/Principles-of-the-Ethical-Practice-of-PH-Version-2.2-68496.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2010

- 54.Views on Health Promotion Online Health promotion code of ethics. 2008. Available at: http://www.vhpo.net/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=24&sid=9dd9553dd81d2ab5c415c48636da039a. Accessed December 7, 2010

- 55.Gregg J, O'Hara L. Values and principles evident in current health promotion practice. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18(1):7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mittelmark MB. Setting an ethical agenda for health promotion. Health Promot Int. 2008;23(1):78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nuffield Council on Bioethics Public Health: Ethical Issues. London, UK: Nuffield Council on Bioethics; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alexander SM, Baur LA, Magnusson R, Tobin B. When does severe childhood obesity become a child protection issue? Med J Aust. 2009;190(3):136–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stubbs JM, Achat HM. Individual rights over public good? The future of anthropometric monitoring of school children in the fight against obesity. Med J Aust. 2009;190(3):140–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anand S, Peter F, Sen A, Public Health, Ethics, and Equity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duncan P, Cribb A. Helping people change—an ethical approach? Health Educ Res. 1996;11(3):339–348 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buchanan DR. A new ethic for health promotion: reflections on a philosophy of health education for the 21st century. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(3):290–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Becker HS. Tricks of The Trade: How to Think About Your Research While You're Doing It. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guttman N. Beyond strategic research: a value-centered approach to health communication interventions. Commun Theory. 1997;7(2):95–124 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guttman N. Ethical dilemmas in health campaigns. Health Commun. 1997;9(2):155–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guttman N, Ressler WH. On being responsible: ethical issues in appeals to personal responsibility in health campaigns. J Health Commun. 2001;6(2):117–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Neill O. Informed consent and public health. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1447):1133–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.MacLean L, Edwards N, Garrard M, Sims-Jones N, Clinton K, Ashley L. Obesity, stigma and public health planning. Health Promot Int. 2009;24(1):88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bayer R. Stigma and the ethics of public health redux: a response to Bell. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(6):800–801 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bell K, Salmon A, Bowers M, Bell J, McCullough L. Smoking, stigma and tobacco “denormalization”: further reflections on the use of stigma as a public health tool. A commentary on Social Science & Medicine's Stigma, Prejudice, Discrimination and Health Special Issue (67: 3). Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(6):795–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(5):941–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shaping the future of health promotion: priorities for action. Health Promot Int. 2007;23(1):98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Porter C. Ottawa to Bangkok: changing health promotion discourse. Health Promot Int. 2006;22(1):72–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ritchie J. Values in health promotion [editorial]. Health Promot J Austr. 2006;17(2):83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bauman A, O'Hara L, Signal L, et al. A perspective on changes in values in the profession of health promotion. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18(1):3–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boivin A, Legare F, Lehoux P. Decision technologies as normative instruments: exposing the values within. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):426–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giacomini M. Theory-based medicine and the role of evidence: why the emperor needs new clothes, again. Perspect Biol Med. 2009;52(2):234–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Greenhalgh T, Russell J. Evidence-based policymaking: A critique. Perspect Biol Med. 2009;52(2):304–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Upshur RE. The ethics of alpha: reflections on statistics, evidence and values in medicine. Theor Med Bioeth. 2001;22(6):565–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weed DL. Underdetermination and incommensurability in contemporary epidemiology. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1997;7(2):107–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clarke A. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Postmodern Turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 83.GfK Bluemoon; Miller K, Tuffin A. Australian Better Health Initiative Phase I—Campaign Evaluation—Quantitative Research Report. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hill D, Chapman S, Donovan R. The return of scare tactics. Tob Control. 1998;7(1):5–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Craig CL, Bauman A, Gauvin L, Robertson J, Murumets K. ParticipACTION: a mass media campaign targeting parents of inactive children; knowledge, saliency, and trialing behaviours. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hamilton N, Bhatti T. Population Health Promotion: An Integrated Model of Population Health and Health Promotion. Ottawa, Ontario: Health Promotion Development Division, Health Canada; 1996. Available at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/php-psp/index-eng.php. Accessed December 4, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Slovic P. Perceived risk, trust and democracy. Slovic P, ed. The Perception of Risk. London, UK: Earthscan; 2000:316–326 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wacquant LJD. Towards a reflexive sociology: a workshop with Pierre Bourdieu. Sociol Theory. 1989;7(1):26–63 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Signal L, Martin J, Cram F, Robson B. The Health Equity Assessment Tool: A User's Guide. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Equity Project Team Four Steps Towards Equity: A Tool for Health Promotion Practice. Sydney, Australia: NSW Health and Health Promotion Service, South East Health; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jones M, Bayer R. Paternalism and its discontents: motorcycle helmet laws, libertarian values, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):208–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Buchanan D. Autonomy, paternalism, and justice: ethical priorities in public health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):15–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Turoldo F. Responsibility as an ethical framework for public health interventions. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(7):1197–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]