Abstract

The Process and Collaboration for Empowerment and Discussion (PACED) approach redefines the goals for employing the performing arts in HIV/AIDS education. Considering the complexity of the epidemic, art can appropriately address HIV/AIDS by placing a greater emphasis on the creative process, engaging people living with HIV/AIDS, and focusing on contextual barriers to prevention and care. This approach was implemented in Ghana in 2006 in the form of the Asetena Pa Concert Party project. An evaluation of the project after its completion showed that it promoted a sense of empowerment among people with HIV and community dialogue about the structural and cultural obstacles to HIV/AIDS prevention, supporting the use of PACED as a viable tool in comprehensive education regarding HIV/AIDS.

According to Augusto Boal, the purpose of art should not be to provide aesthetic pleasure or an escape from reality but to contribute to society's ongoing attempts to solve its problems.1 Although art alone cannot solve the complicated problems associated with the HIV/AIDS epidemic (or any other social phenomenon), it can open new avenues for thought, discussion, innovation, and action. Carol Becker has argued that art can stimulate the imagination to visualize a better world and then push it to its realization.2 In Boal's conceptualization, this boundless realm of the imagination allows thoughts and feelings to be safely explored before they are adapted to reality.1 We base our discussion of art on this conceptualization.

The Process and Collaboration for Empowerment and Discussion (PACED) approach redefines the goals for using the performing arts in HIV/AIDS education. It suggests a shift from using art as entertainment to convey messages regarding HIV/AIDS toward a more participatory, communal, and empowering approach made possible through the use of art.

The theoretical guidelines for the PACED approach are well established in their respective fields: development communication, entertainment–education (also known as “edutainment”), the theater of the oppressed and theater for development, and social and behavioral theories pertaining to HIV/AIDS. PACED brings together elements of these theories to develop a new framework.

Entertainment–education has been a predominant source of arts-based methods. It uses Bandura's social learning–social cognitive theory, according to which “learning can occur through observing media role models.”3(p296) Through the provision of positive, negative, and transitional role models, certain values are encouraged or discouraged, ultimately influencing behavior change on the part of the audience. When art is conceptualized merely as entertainment, however, it constrains the abilities described by Becker and Boal. To make full use of art, we must reconsider our goals and strategies.

The PACED approach was initiated in Ghana, West Africa, in 2006. A group of 5 popular Ghanaian performing artists and 5 HIV-positive individuals collaboratively created and performed a concert party—a popular performance art form in Ghana that includes music, comedy, and drama4,5—named Asetena Pa, meaning “good living” (or, in this context, “positive living”) in Twi, the most widely spoken local language in Ghana. The performance was based on the life stories of the participants and issues that had surfaced during a preperformance workshop.

The comedy act broke the ice with jokes about relationships, sex, and condoms. The main act was a play about a woman whose husband has died of AIDS. After discovering that she is HIV positive, she meets a wealthy, handsome old friend who wants to marry her. She faces the dilemma, which she shares with the audience, of whether or not to tell him about her HIV status.

The performance, which included interaction with the audience and ended with the actors introducing themselves (including disclosing their HIV status), shattered many preconceptions and was a trigger to open discussions about HIV/AIDS, sex among HIV-positive individuals, gender issues, and more. The performance toured 11 towns and villages in Ghana, after which it was qualitatively evaluated with respect to its impact on audiences and the participants.

SHIFTING AWAY FROM THE MESSAGE

The flaws of persuasive communication or “messaging” often begin with the top-down manner in which the problem is framed. According to Melkote and Steeves,

[m]any of the problems faced by marginalized groups are caused by complex social contexts, yet campaigns do not usually address social-economic and political constraints.6(p242)

For example, a major limitation of the common ABC approach (abstinence, being faithful, condom use) is that it focuses on the individual's choice in changing behavior while neglecting contextual factors. A woman's risk is not simply dependent on her behavior; it is also dependent on the behavior of her husband and on the cultural, economic, and power dynamics that affect her actions.7 Culturally appropriate interventions are needed that acknowledge and address such issues.8

FROM PRODUCT TO PROCESS

A common practice in creating art-based interventions is for a government or funding agency to decide on the message to be delivered, hire the artists, and ask them to produce a performance or artwork that delivers that message. Some agencies even require that a specific word be repeated a minimum number of times during the production (O. Madiang, MA, Africa Research Conference in Applied Drama and Theater, oral communication, November 2009). The result is that artists become concerned with creating a final product that will satisfy funding agencies, neglecting the creative process and in-depth engagement with the social problem to be addressed.

Scholars and professionals frustrated with this top-down method have recommended moving toward a participatory approach. Campbell has advocated for “local people collectively to ‘take ownership’ of the problem”, meaning that they should engage in a critical analysis of the problem and an exploration of feasible solutions.9 Theater of the oppressed, a theory developed by Boal,1 provides a foundation for Campbell's viewpoint. Inspired by Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed,10 theater of the oppressed is used to assist audiences in understanding their oppression and exploring mental and emotional liberation. Unlike the usual prewritten play, audiences—not directors or actors—determine the course of the performance.

A parallel shift is occurring in development communication. Mda documented the politics behind “participatory communication”:

Whereas in persuasive communication mass media are used to beam messages … in participatory communication the message can emanate from any point, and be added to, questioned, responded to, from any other point.11(p36)

Theater for development (TFD)—the integration of development communication and theater of the oppressed—has made significant advances. However, if a TFD project is to be true to its original goals, performers and communities must have absolute freedom to determine the themes and content of the performances. Using TFD to address a predetermined issue (such as HIV/AIDS) stands in contrast to the idea that the topic of the performance should emanate from the community. Obtaining funding without such restrictions has been a major obstacle.11–13 Consequently, TFD has been deployed primarily by small, grassroots organizations, whereas governments and larger agencies tend to favor top-down messaging.14

In process-oriented work, before thinking about the final product—the content of the performance or artwork—artists are asked to analyze the social problem, engage with it intellectually and emotionally, and explore and form their own ideas through such engagement. This structural and participatory approach has been advocated in HIV/AIDS prevention efforts.15–19

This approach does not necessarily mean that there is no delivery of messages. In all forms of human communication we constantly engage in delivering messages, consciously or not. Osita Okagbu drew from his experience in working on a TFD project in Ghana to explain the difference between product-oriented and process-oriented work:

Theatre as a form of cultural action is almost always loaded with messages and possible meanings which an audience can read into or out of it[;] whether these messages or meanings are intended or are unintentional is quite beside the point. Rather … the issue of the message being carried, who is responsible for it, who is carrying it and the manner in which it is carried are paramount and definitely more important than the actual message itself.12(p25)

Thus, more important are the following questions: Who decides on the messages? and What is the manner of delivery? These 2 concepts serve as the foundation for the PACED approach.

COLLABORATIONS BETWEEN ARTISTS AND PEOPLE WITH HIV/AIDS

The strategy toward HIV/AIDS education in the earlier stages of the epidemic (the 1980s and early 1990s) was “the fear appeal.” This method was based on the assumption that fear of infection would motivate people to protect themselves.20,21 Today the public health community has realized that this strategy worsened the severe stigma faced by people living with HIV/AIDS.22–24

In recent years, perhaps in an attempt to correct the damage caused by scare campaigns, the concept of showing compassion to people living with HIV/AIDS has been advocated worldwide. For example, in 2002 Ghana initiated the “Reach Out, Show Compassion” program, in which the government partnered with religious leaders to promote compassion for people living with HIV/AIDS. Although evaluations of this program showed that it increased the likelihood that people would take care of a family member with HIV/AIDS and decreased people's desire to isolate individuals with the disease, the program was unable to significantly change people's wish to keep a family member's HIV status a secret or their attitude that people with HIV/AIDS are to blame for their infection.25

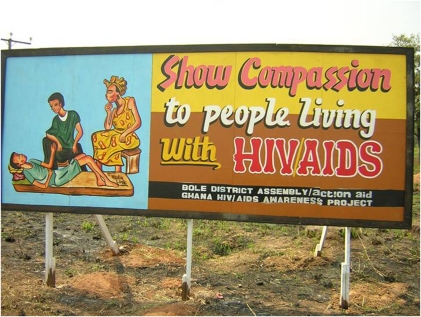

Another example is the “Show Compassion” billboards in Ghana (Image 1). In both of these images, the person with HIV/AIDS appears as a weak, dying victim, as was customary in earlier portrayals of HIV-positive individuals. Also, the people showing compassion are situated higher than the person with HIV/AIDS, looking down at him or her.

“Show Compassion” billboards photographed in Ghana in 2007 Photos by Galia Boneh.

In the context of HIV/AIDS education, the concept of compassion has the potential to create an uneven power dynamic, in which the receiver of compassion is rendered as in need of mercy or pity and dependent on the giver of compassion. This observation leads to the following questions: Is it compassion that people with HIV/AIDS need from their families, the general public, and the government, or do they need the power to exercise their own human rights and not be dependent on the goodwill of others? Does the concept of compassion fuel the cycle of victimhood, and, if so, what alternative would be more inspiring, liberating, and useful in countering the spread of the epidemic?

For HIV-positive individuals, claiming their human right to participate in life is the first step in beginning the process of empowerment. Max Navarre, himself a person living with HIV/AIDS, wrote in the early days of the epidemic in the United States:

Convincing the public and ourselves that people with AIDS can participate in life, even prosper, has been an uphill struggle… . I'm talking about the business of living, of making choices, of not being passive, helpless, dependent, the storm-tossed objects of the ministrations of the kindly well. These are the pejorative connotations of victim that [people with AIDS] find unacceptable.26(p145)

People living with HIV/AIDS in Ghana, as in several other developing countries, still carry connotations similar to the ones mentioned in Navarre's essay.27,28 In 1999, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS initiated the “Greater Involvement of People Living with HIV/AIDS” campaign and outlined several areas in which people with HIV/AIDS could participate.29 However, these individuals face several obstacles to involvement, including fear of public disclosure and negative stereotyping by employers.30 Successful interventions require that messages be created, designed, and implemented by the people most affected by the epidemic.31

There is also a need to involve both men and women so that the unique barriers faced by each can be addressed. Gupta described a continuum on how to approach gender issues in HIV interventions, from gender-insensitive approaches that reinforce stereotypes to, ultimately, transformative approaches and approaches that empower in an attempt to create more equitable relationships and alter societal norms.32

The PACED framework seeks such transformation and empowerment. HIV-positive men and women are full and equal participants in all stages of the creative process and performance. The collaboration between artists who possess the skills of local performance, and women and men living with HIV/AIDS who have direct experience with the issues associated with the epidemic, allows for the creation of art that is grounded in both culture and reality. The image of people with HIV/AIDS singing, dancing, acting, voicing—being alive, vocal, and confident—counters the more common view of these individuals as passive, dying victims.

Similarly, the interaction between popular artists and people with HIV/AIDS on stage—embracing, joking, singing, and acting together—reflects the process they underwent as a group and sends out a clear message of acceptance. The project directors' role is merely to guide the process of forming and framing the voices of the participants. With these elements in place, the content of the performance is of secondary importance. The images formed and delivered through the process of empowerment and the artistic collaboration between artists and people living with HIV/AIDS constitute the message.

PERFORMANCE AND THE COMMUNITY

The HIV/AIDS epidemic has largely been analyzed at the macro-social and micro-social levels.9 The macro-social level focuses on the ways in which poverty, gender inequality, and global capitalism shape the contexts of the epidemic. At the micro-social level, sexual behavior is linked to properties of the individual, such as cognitive processes, attitudes, sense of personal vulnerability, and perceived social norms. Underlying behavioral theories include the Health Belief Model, the theory of reasoned action, and AIDS risk reduction and management theory.33

One important conceptual problem with these theories is that they target the individual and disregard the influence of structural variables (the macro-social level).18 Research has shown that community structure and dynamics can affect people's vulnerability to HIV infection and the success of individual-level interventions.15,17,34 For example, such interventions that target the sexual behavior of women tend to be ineffective, in that women's behavior is less connected to choice than to duty or livelihood.19,35,36

The community, as a group of individuals with a shared culture and operative social networks living within a close geographical area, is becoming increasingly recognized as a potent locus of change.7,9,19,37–39 Stockdale showed that messages about HIV/AIDS are more successful if the target is social identity rather than individuals.40 Furthermore, Campbell noted that

communities serve as key mediators between the macro- and the micro-social levels of analysis… . Local communities often form the contexts within which people negotiate their social and sexual lives and identities.9(p3)

Campbell also discussed the need to “develop policies and interventions in social and community contexts that enable and support health enhancing behaviors” and, by doing so, create what she called “health enabling community contexts.”9(p11) According to Gupta et al., this strategy

can involve a more participatory approach, engaging communities in the process of problem-solving, building on local knowledge to generate an indigenous, organic response.15(p768)

Folk media allow for participation of the community, generate discussion, and provoke a reconsideration of social norms. According to Melkote and Steeves, folk media “are part of the rural social environment and, hence, credible sources of information to the people.”6(p253) In particular, live performances are attended by an assortment of community members, making them shared experiences. Consequently, new discourses are introduced into the ongoing process of change, redefinition, and revisiting of groups' identities and values. The shared experience generates discussion in the community hours, days, and weeks after the performance and can be referred to in discussions or arguments on related topics.41 In this way, the new discourse on HIV/AIDS becomes part of the tradition-making process.

With respect to HIV/AIDS and sexual behavior, a live performance attended by members of both genders can serve as an opening for intimate discussions. In Ghana, for example, it is uncommon for men and women to discuss matters of sex and intimacy openly.42 However, jokes and songs indirectly alluding to sex are part of everyday discourse, especially among young people. Through performance, these forms of expression can be used as gateways for more serious discussions in the public sphere. Gausset compared 3 interventions that took place in rural Zambia, one of which included drama.43 A survey indicated a clear increase in the use of condoms in the areas that had been toured by the drama group. Gausset attributed this outcome to the drama being understandable, interactive, easy to identify with, and useful in instigating dialogue across genders and generations:

[T]he simple fact that both men and women, older and younger people saw the same play and discussed the topic afterwards made it possible for people to reach a new consensus on the acceptance and use of condoms, thus opening the way for a change in the rules of social behavior and in the negotiation of sexual relationships.43(p516)

Unlike mass media, live performance also allows for active participation in the intervention itself. According to Mda, theater has the advantage of being a potentially democratic medium “in which audiences may play an active role in medium-programming, and therefore in producing and distributing messages.”11(p2) The democratic nature of such live performances not only allows audiences to participate in the design of the specific messages but also establishes an interactive relationship between deliverer and receiver and lays the foundation for taking ownership of the problem. On a practical level, Boal's theories are based on the premise that active participation of audiences in the theatrical experience can stimulate and prepare them for change in real-life situations.

Finally, the community's recognition of the limited power of individuals to reduce their personal risk or live positively with HIV/AIDS in the context of profound structural problems and unsupportive social environments is crucial in enhancing people's ability and willingness to change their behavior.

DESIRED OUTCOMES OF PACED

Following the rationale described earlier, PACED sets out to accomplish 2 primary goals: empower people with HIV/AIDS and initiate a public discourse on HIV/AIDS that includes structural and contextual issues.

Empowerment of People Living With HIV/AIDS

Rowlands defined 3 types of empowerment: (1) personal empowerment (developing individual consciousness and confidence to confront oppression), (2) relational empowerment (an increased ability to negotiate and influence relational decisions), and (3) collective empowerment (action at the local or higher level to change oppressive social structures).44 Oppression, in these definitions of empowerment, can be thought of as “[t]he state of being caught among systematically related forces and barriers that restrict one's options, immobilize, mold and reduce.”45(p2)

Boon and Plastow noted that empowerment does not necessarily mean elimination of oppression. Rather, empowerment has to do with

the liberation of the human mind and spirit, and with the transformation of participants who see themselves—and are often seen by others—as subhuman, operating only at the level of seeking merely to exist, into conscious beings aware of and claiming voices and choices in how their lives will be lived.46(p7)

People living with HIV/AIDS may not be able to entirely overthrow the larger social, economic, and political structures that determine their oppression. But through the processes of liberation, recognizing these forces, and claiming their voices and choices, they can achieve personal empowerment, freeing themselves of internal oppression and self-blame. These processes can lead to relational empowerment and collective empowerment, which may or may not result in actual change in oppressive structures. By collaborating and engaging with HIV-positive individuals, the PACED approach seeks to empower them to generate discussion, educate, and share personal experiences that can be more useful in encouraging preventive behavior than the scare methods and panic that ultimately lead to denial and fatalism.

Structural and Contextual Issues

Recognizing the role of the community in changing behavior and attitudes and the limitations of top-down messaging, the PACED approach seeks to trigger a public discussion that is grounded in, and yet challenges, reality. In such a way, the resulting performances question common attitudes, opening the possibility of change. Examinations of process and performance are thus guided by the following 2 questions: (1) Does the process or performance acknowledge and delve into the complexity of reality? and (2) Does the process or performance bring to question and challenge widely held stereotypes and assumptions?

The first question addresses whether participants focus their efforts on designing simplistic, slogan solutions, such as the ones often seen on television or billboards, or whether they recognize through the process that there are no simple solutions and that structural, cultural, and psychological factors all play a role in determining individuals' behaviors and risks. These realizations will be reflected and addressed in the production. The second question pertains to whether the creative process compels the participants to probe widespread assumptions and confront their own prejudices. Ultimately, this approach will lead them to create a product that, at worst, does not reinforce misconceptions and, at best, challenges them.

If the process is deep and exhaustive, the product will possess these qualities as well. Audiences cannot be expected to engage in depth if the performers themselves have not done so. If the creative process is designed to provide the time and the willingness to “get messy”—to deal with the uncomfortable, the internal, and the complex—the performance will be sufficiently provocative and authentic to stir up similar conversations among audience members.

ASETENA PA CONCERT PARTY PROJECT

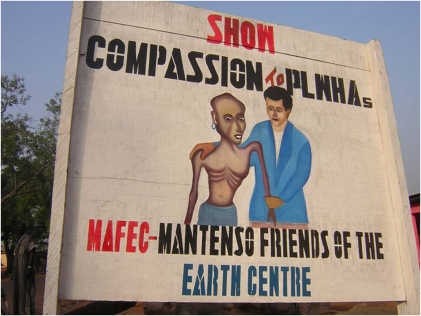

As mentioned earlier, the Asetena Pa Concert Party project, implemented in 2006, engaged 5 Ghanaian popular artists and 5 individuals with HIV/AIDS in a process that delved into issues related to HIV/AIDS and created a performance that was largely based on the experiences of the participants (Images 2 and 3). Thus, the project reflected the PACED approach in that it focused on process, involved a collaboration with HIV-positive individuals, and used performance to engage with the community. The target populations of the project were young adults from poor rural and urban communities, in approximately the 16- to 35-year age group.

Asetena Pa Concert Party poster advertising the performance.

Participants in the Asetena Pa Concert Party project: HIV-positive performers, professional actors, and project directors. Photo by Ari Libsker.

People living with HIV/AIDS were recruited through support groups. After a presentation on the project, interested members were invited to auditions and interviews. The individuals selected varied sociodemographically. The 4 participating women were a 21-year-old pepper trader from northern Ghana, a 27-year-old city dweller in Accra with 1 child, a 42-year-old charcoal trader with 4 children, and a 58-year-old devout Christian with 3 children. The single male participant was a 40-year-old from northern Ghana who was a father of 6. Selected participants had to be approved by their medical doctor to ensure that their health would not be hindered by the long hours of rehearsing and touring.

Recruitment of artists was targeted. After researching popular performers in Ghana, we approached individuals and conducted interviews to select the participants. The artists also varied in their sociodemographic characteristics. The 3 participating men were a 28-year-old university graduate and television star, a well-known 50-year-old actor, and a 35-year-old comedian and farmer. The 2 women taking part, one in her 40s the other in her 60s, were both well-known actresses.

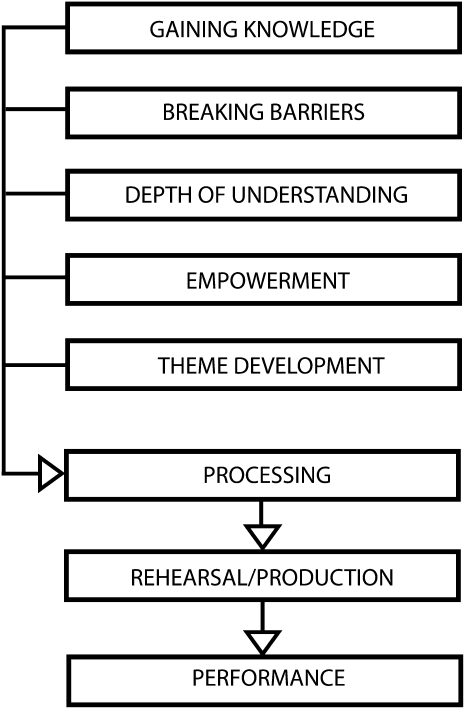

The process of building a relationship between artists and people with HIV while generating the discussion for the performance followed 8 stages (Figure 1). The period devoted to the creative process (beginning in stage 2) was 11 days long and took place in a secluded space (Aburi Gardens), where participants lived together and worked 8 hours a day. The stages were as follows.

FIGURE 1.

The 8 stages of the Process and Collaboration for Empowerment and Discussion (PACED) process in the Asetena Pa Concert Party project. Arrow notes progression to next stage, with each building on the prior stages.

Knowledge acquisition: In this stage, each group (people with HIV/AIDS and artists) separately underwent a series of information-based sessions delivered by health professionals, and members were free to voice their fears and anxieties about working with the other group.

Elimination of barriers: Through movement, music, and theater games, the participants learned about each other while creating an atmosphere of trust.

Depth of understanding: Three major activities, sharing of personal stories, debates, and theater exercises, stimulated intellectual and emotional discussions on the complex reality surrounding HIV/AIDS.

Empowerment: Through theater of the oppressed exercises, the participants explored possibilities and sources of power within oppressive situations.

Theme development: Participants determined relevant issues to address in the performance. They voiced ideas, voted, and then chose a major topic, recognizing that some of the other issues could be represented as subtopics.

Processing: Guided by the theme chosen by the group, the project directors processed the material generated throughout the stages into a storyline. After presenting it to the group, they adjusted it according to group members' feedback.

Rehearsal and production: The participants prepared for the performance and advertised it in the nearby community. Before going on tour, the group spent additional time on rehearsals, production, and advertisements.

Performance: The performance started with 2 to 3 hours of live music to attract the audience. An opening comedy act broke the ice about sex and gender relations and included a funny—but accurate—condom demonstration. The dramatic portion of the performance centered around an HIV-positive woman, Adu, whose husband died of AIDS and didn't tell her of his status for fear that she would leave him. A year later Adu meets Aboloway, a handsome and well-to-do man who wants to marry her. Adu faces a dilemma: should she tell him of her HIV status? The audience became aware that HIV-positive individuals were participating in the performance only at the end, when the protagonist declared, “We are a group of 5 professional actors and 5 people living with HIV/AIDS.” As the performers formed a line embracing one another, the audience was presented with several questions: “Can you tell who has HIV and who does not? If you were Adu, would you tell Aboloway of your HIV status? If you were Aboloway, would you stay or would you leave?” The performers then gave short testimonies that included their name, HIV status (positive or negative), and a statement about themselves (Image 4).

Asetena Pa Concert Party performers forming a line during the final scene of the performance. Photo by Galia Boneh.

After the performance, performers interacted with audience members, answered questions, and gave out the phone number of an Asetena Pa hotline staffed by one of the performers with HIV/AIDS. Informal interaction followed; in more than half of the performances, discussions with audience members continued up to 2 hours after the show had ended. We noted that the sociodemographic characteristics of most of the performers were similar to those of the audiences, whose members were primarily aged between 16 and 40 years, lived in semirural and small towns throughout the country, and worked mostly in agriculture and trade.

As noted earlier, the primary goals of the PACED approach are to empower people with HIV/AIDS and generate discussion about the structural and contextual issues surrounding HIV/AIDS. We conducted interviews with audience members and participants and thematically analyzed data from these interviews to determine the success of the Asetena Pa Concert Party project in achieving these goals.

METHODS

Data were derived from focus group discussions held on the day after the performance in 4 of the towns where performances were held: Yapei, Damongo, Bole, and Bamboi, all in the northern part of Ghana. In each location, 4 focus groups were held, 2 with women and 2 with men (totaling 16 focus groups in all). The groups were separated according to gender, to ensure that men and women would be comfortable sharing their reactions and thoughts and that both would be heard equally. Each group was attended by 6 to 11 participants roughly between the ages of 18 and 35 years.

The focus group moderators were 2 university students (one male, one female) who were fluent in both Gonja and Twi. Moderators underwent 3 days of training and followed an outline of 11 questions regarding impressions, thoughts, and feelings about the performance; actions of specific characters in the play; and testimonies of the participating HIV-positive performers. Also addressed were the relationship of the performance to reality and whether the participants had learned anything new or made any personal resolutions as a result of the performance.

All meetings were recorded and later transcribed and translated to English by university students who were native Gonja and Twi speakers. The accuracy of the translations was confirmed by one of the performance's codirectors, Iddi Saaka, also a native speaker of Gonja and Twi. Participating artists and HIV-positive individuals were interviewed informally by Galia Boneh after the workshop and during a reunion in Accra in 2007.

RESULTS

Focus group discussions and interviews indicated that the performance gave people with HIV a greater sense of empowerment while generating discussion about the contextual barriers to HIV prevention among both participants and the community.

Empowerment of People With HIV/AIDS

Interviews suggested the early development of our 3 definitions of empowerment: personal empowerment, relational empowerment, and collective empowerment. In relation to personal empowerment, one of the participants with HIV/AIDS commented on her newfound confidence after the workshop:

Before the project I used to feel very shy about the fact that I have HIV, but now I feel very confident and proud of myself. I don't care—if I am not depending on you for food, you can say what you want. I have decided to live the number of years God has given me.

With respect to relational empowerment, we learned how participants were able to counsel others. For example, Lydia (a pseudonym) from Aburi talked to Ama (one of the HIV-positive Asetena Pa performers) after the performance, and they exchanged phone numbers. Five months later, Lydia called Ama and told her that she wanted to be tested for HIV. Ama traveled an hour and a half to meet her and take her to an HIV/AIDS clinic. Lydia tested positive but responded well to the diagnosis as a result of Ama's counseling.

While a more longitudinal analysis would be required to evaluate collective empowerment, 3 support groups, each numbering approximately 30 people, were formed in 3 of the towns as a direct result of the performance. Dennis (a pseudonym) from Navrongo, who had been suspecting for some time that he was HIV positive but did not have the courage to undergo an HIV test, went for testing after the performance and was found to be HIV positive. After receiving counseling and advice from Courage (another HIV-positive Asetena Pa performer), Dennis formed a support group in Navrongo numbering 27 members.

These and other instances show how the empowerment of HIV-positive people as individuals can affect the well-being of others and the collective stance and status of people living with HIV/AIDS. The formation of support groups by individuals who were inspired and encouraged by the performance is a sustainable and important result of the project, in that it continues to provide people with HIV social and emotional support as well as assistance with food, medical treatment, and income generation.

Interestingly, one of the HIV-positive performers in Asetena Pa decided to leave her support group after the project because she believed that she no longer needed it. She no longer required the food and income generation assistance of the support group because the stipend she received through the project had allowed her to start a trade. In addition, she had worked through much of her insecurity, shame, and fear through the workshop, and thus she no longer felt the need for emotional and social support from other people with HIV/AIDS. Such outcomes show that a support group is necessary to overcome a difficult stage in the life of a person with HIV/AIDS, but that a process of empowerment can assist the individual in moving past that stage, helping him or her become independent and return to economic and social activity as a full and equal member of society.

Discussion of Structural and Cultural Issues Surrounding HIV/AIDS

To evaluate the level and content of discussion in the focus groups, we returned to the issues raised earlier: whether the process or performance acknowledged and delved into the complexity of reality and whether it challenged widely held attitudes, stereotypes, and assumptions. Questions raised during focus group discussions to evaluate whether the performance achieved these goals included the following: Do you think this is a story that could happen in real life? Which parts are realistic and which are not? If you were in a similar situation to that of the main characters, how would you act? What did you feel when the actors announced their HIV status?

In relation to the first issue, one of the female audience members commented on women's lack of control over the promiscuity of men:

You see, you can't tell your husband not to look for other women. Even his own mother can't tell him not to look for other women. Because of that, it's only God who will be protecting us from that sickness. Because when you see a woman and you say you love her, you don't know if she's the one who has it or not… . We don't have the power to control our husbands.

Throughout the process, issues of gender, class, and stigma surfaced in theater exercises, discussions, and arguments. According to one of the HIV-positive participants:

We had a lot of arguments. For example, Courage was all the time boasting how he has no problem telling the whole world that he has HIV. He says it so much that people no longer believe him that he has it. And he says we should do the same, that we shouldn't feel shy to say it. But we told him, you are a man. You are not depending on anyone for food. We women have to depend on our families to survive. We can't just go about doing or saying whatever we want.

Issues of gender were treated not only as they appeared in sectors of society but also as they manifested themselves in the personal lives of the group members and in the dynamics between them. As shown in the preceding quotation, revealing one's status publicly carries different meanings and consequences for a man than it does for a woman. This factor was an issue during the creative process, and it was also a subject of discussion among audience members. HIV-positive individuals were not requested by those involved with the project to come out publicly, and in fact they were constantly reminded not to do so if they did not feel comfortable. In the end, they all chose to come out publicly because they felt that it would make the performance stronger.

In terms of the second issue, the image of the healthy-appearing performers provoked a lively debate among audience members regarding whether the testimonies of people living with HIV/AIDS were true. The following excerpt from a male focus group discussion illustrates the ways the performances challenged assumptions among audience members:

Participant 1: I was happy because if they hadn't disclosed to us we wouldn't know, so it shows that you can't tell someone's HIV status from the way their body looks.

Participant 2: There wasn't any difference between them [HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals], so it means that what a normal fellow can do, a person with AIDS can equally do.

Participant 3: It has given courage to people living with AIDS that after all they can still continue with their lives.

Participant 4: I was so happy because though some were positive and some were not, they all came together to act the play and related very well with one another. This means that we can also do things together with our own folks who are HIV positive.

Through the use of performance and collaboration with HIV-positive individuals, the Asetena Pa Concert Party was able to engage with the community to initiate the process of empowerment, trigger conversations related to the structural issues associated with HIV/AIDS, and challenge previously held notions.

DISCUSSION

Entertainment–education is a potent means of triggering change in society. However, the use of art in its fullest sense—not simply in terms of its entertainment qualities—has a larger and broader potential to bring about meaningful change. This change can be achieved through a reconsideration of the goals and methods in designing arts-based interventions. The PACED approach proposes a movement from a narrow use of performance to deliver messages toward the potential of art to empower and provoke critical discussion in the community. The approach is based on theories such as TFD and theater of the oppressed, as well as evidence showing that structural and community-focused programs are integral in HIV/AIDS interventions. When these concepts are integrated, the result is an artistic collaboration between people with HIV/AIDS and professional artists that emphasizes an in-depth creative process focused on the topics of HIV/AIDS and gender.

A performance can be effective in initiating change, but on its own it cannot sustain it. For sustained changes to occur, 2 basic elements must be integrated into the intervention. First, education must be complemented with services so that people can take actions that are based on what they learn. Second, further activities are required to create an ongoing discussion that may lead to lasting change in discourse and social norms.

The Asetena Pa Concert Party would have been significantly more successful if we had spent more time in each location to conduct additional educational activities, provide HIV/AIDS services such as voluntary counseling and testing, upgrade the HIV/AIDS services offered at the local clinics, and provide ongoing mentorship to the support groups. Research has shown that interventions must have a comprehensive HIV/AIDS education and intervention strategy to achieve maximum impact.15,31,34 We believe that models that include the PACED principles, by focusing on the community, seeking to engage and empower people with HIV, and addressing the structural determinants of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, will be best suited to effect lasting change.

As the PACED approach is used in future projects and different locales, associated obstacles should be noted. The costs of implementing the approach and touring with artists and HIV-positive individuals may be a barrier, given that they exceed the traditional costs of hiring artists to deliver a preformed message. PACED directors must carefully guide the process without controlling it, and they must possess a strong understanding of local customs. Participants must be able to fully commit to the project, although this obstacle can probably be overcome if participants are paid properly.

In addition, further empirical support is essential. Gupta et al. outlined the challenges involved in assessing structural approaches, including difficulties in evaluating long-term effects when multiple interventions and factors can influence outcomes and difficulties in reproducing a program designed for a specific context.15 Consequently, randomized controlled trials are not amenable to such methods because of the limitations involved in controlling these confounders.15,18 Rather, what is needed is a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods based on a theoretical model or framework.

Also, explorations of process are necessary to provide areas in which researchers can evaluate change.15 The 8 stages of the PACED method provide a theoretically based outline that allows one to evaluate changes in beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge. Pretests can be administered to members of each group (actors and people living with HIV/AIDS) before they meet, with evaluations taking place after each stage or at the culmination of the process. Long-term follow-up would then be required to sustain behavior changes.

Similarly, audience quantitative and qualitative methods, including surveys, focus groups, and interviews, could be used to evaluate audience members' beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge before and after the performance. In addition, they could be followed up over time to assess long-term changes in attitudes and behaviors. Behavior change in communities can be assessed by monitoring condom sales, increases in the use of voluntary counseling and testing services, and increases in local support group memberships.

In her book Letting Them Die: Why HIV/AIDS Programs Fail, Catherine Campbell concluded:

Sexual behavior change is more likely to come about as the result of the collective recognition [emphasis added] of young people's gender and sexual identities than through individual decisions to change one's behavior… . Unless people develop a critical awareness [emphasis added] of the way in which social relations serve as obstacles to behavior change, and a vision that things could be different, they are unlikely to be motivated to change their behavior.9(p133)

These 3 elements—collective recognition, critical awareness, and vision—can be effectively achieved through art shared in the community if the full potential of art is used and honored in creative processes and performances.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided through the International Institute and Graduate Division of the University of California, Los Angeles. Funding for the Asetena Pa Concert Party project was provided by the Rosenthal Charitable Gift Fund and Threshold Foundation.

Many thanks to Iddi Saaka, codirector of the Asetena Pa Concert Party project; to the Asetena Pa project participants; and to David Gere, Courtney Burks, and Anoosh Jorjorian for their insightful comments on the article.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, Los Angeles. All participants and interviewees provided informed consent.

References

- 1.Boal A. Theatre of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Theatre Communications Group Inc; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker C. The Subversive Imagination: Artists, Society and Social Responsibility. New York, NY: Routledge; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singhal A, Rogers EM. Combating AIDS: Communication Strategies in Action. New Delhi, India: Sage Publications; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole CM. Ghana's Concert Party Theatre. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barber K, Collins J, Ricard A. West African Popular Theatre. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melkote SR, Steeves HL. Communication for Development in the Third World: Theory and Practice for Empowerment. London, England: Sage Publications; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):13–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett T, Parkhurst J. HIV/AIDS: sex, abstinence, and behaviour change. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(9):590–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell C. Letting Them Die: Why HIV/AIDS Prevention Programs Fail. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mda Z. When People Play People: Development Communication Through Theatre. Johannesburg, South Africa: Witwatersrand University Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okagbu O. Product or process: theatre for development in Africa. : Salhi K, African Theatre for Development: Art for Self Determination. Exeter, England: Intellect Books; 1998:23–42 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banham M, Gibbs J, Osofisan F, African Theatre in Development. Oxford, England: James Curry; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomaselli KG. Action research, participatory communication: why governments don't listen. Afr Media Rev. 1997;9(1):1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker RG, Easton D, Klein CH. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S22–S32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piot P, Bartos M, Larson H, Zewdie D, Mane P. Coming to terms with complexity: a call to action for HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9641):845–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E, et al. Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1706–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigby K, Brown M, Anagnostou P, et al. Shock tactics to counter AIDS: the Australian experience. Psychol Health. 1989;3(3):145–159 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bray F, Chapman S. Community knowledge, attitudes and media recall about AIDS, Sydney 1988 and 1989. Aust J Public Health. 1991;15(2):107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalipeni E, Craddock S, Oppong JR, Ghosh J, HIV and AIDS in Africa: Beyond Epidemiology. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slavin S, Batrouney C, Murphy D. Fear appeals and treatment side-effects: an effective combination for HIV prevention? AIDS Care. 2007;19(1):130–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treichler PA. How to Have Theory in an Epidemic: Cultural Chronicles of AIDS. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boulay M, Tweedie I, Fiagbey E. The effectiveness of a national communication campaign using religious leaders to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana. Afr J AIDS Res. 2008;7(1):133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navarre M. Fighting the victim label. : Crimp D, AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1988:143–145 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mbonu NC, van den Borne B, De Vries NK. Stigma of people with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. J Trop Med. 2009;2009:145891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ulasi CI, Preko PO, Baidoo JA, et al. HIV/AIDS-related stigma in Kumasi, Ghana. Health Place. 2009;15(1):255–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.From Principle to Practice: Greater Involvement of People Living With or Affected by HIV/AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy CM, Cain R. The involvement of people living with HIV/AIDS in community-based organizations: contributions and constraints. AIDS Care. 2001;13(4):421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372(9639):669–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta GR. Gender, sexuality and HIV/AIDS: the what, the why and the how. Paper presented at: XIII International AIDS Conference, July 2000, Durban, South Africa: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change in HIV risk behavior. : Peterson J, DiClemente R, Handbook of HIV Prevention. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2000:3–56 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merson MH, O'Malley J, Serwadda D, Apisuk C. The history and challenge of HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):475–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Exner TM, Dworkin SL, Hoffman S, Ehrhardt AA. Beyond the male condom: the evolution of gender-specific HIV interventions for women. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:114–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melkote SR, Muppidi SR, Goswami D. Social and economic factors in an integrated behavioral and societal approach to communications in HIV/AIDS. J Health Commun. 2000;5(suppl):17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heise L, Elias C. Transforming AIDS prevention to meet women's needs: a focus on developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):931–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkins C. HIV/AIDS and culture: implications for policy. : Rao V, Walton M, Culture and Public Action. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2004:260–280 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(4):299–307 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stockdale J. The self and media messages: match or mismatch? : Markova I, Farr R, Representation of Health, Illness and Handicap. London, England: Harwood; 1995:31–48 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kapchan DA. Performance. J Am Folk. 1995;108(430):479–508 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oppong C, Oppong M, Odotei IK. Sex and Gender in an Era of AIDS: Ghana at the Turn of the Millennium. Accra, Ghana: Sub-Saharan Publishers; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gausset Q. AIDS and cultural practices in Africa: the case of the Tonga (Zambia). Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(4):509–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowlands J. Questioning Empowerment: Working With Women in Honduras. London, England: Oxfam; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frye M. Politics of Reality: Essays in Feminist Theory. Freedom, CA: Crossing Press; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boon R, Plastow J, Theatre and Empowerment; Community Drama on the World Stage. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]